KOUT, YACINE, Ph.D. Breaking Down the Enchantment: A Critical Autoethnography

of Video Gaming (2019)

Directed by Dr. Leila Villaverde. 298 pages.

Video games are flooding our everyday lives from our phones to our schools. Our

understanding of this medium is still developing as it shapes players’ sense of self and

their view of the world. This study contributes to bridging that gap by questioning the

educative power of video games and their impact on our society through an

autoethnographic lens. I analyze my video gaming experiences by journaling, field

noting, and crafting epiphanies that represent my history with this medium. I use critical

pedagogy as a theoretical framework to unpack and dismantle my experiences as a long

standing member of the video gaming community. I use critical themes such as identity

building, meaning making, and oppression to make sense of my data. Through these

themes, I answer my two central research questions: How did I navigate the video

gaming culture as a student of critical pedagogy and in what ways do video games lend

themselves to the teaching of critical pedagogy.

Using a critical lens allows this study to deconstruct unexamined experiences that

shape player identities. To answer my research questions, I use the concept of

enchantment to capture the complexity of the stories I have grown up with, both the

power I have drawn from them to build a sense of identity and my naïveté in overlooking,

minimizing, or ignoring problematic and oppressive behaviors tied to these stories. I

share how the wording of my experiences pushed me into adopting a new identity that

reconciled my history as a video game player and my identity as a student of critical

pedagogy. Through the deconstruction of my experiences, I also identified video gaming

tools that lend themselves to the teaching of critical pedagogy. I share how these tools

can be used in the classroom to help players/students question their own thinking, name

their prejudice, and identify oppressive social systems. My study echoes Bochner’s

concept of a story of “two selves,” a space that allowed me to better understand the

culture I am part of and my role in it. My moving from an enchanted understanding to a

continuous questioning of my engagement with a medium that holds a central place in my

life constitutes an invitation to examine the stories we have all grown up with. In

identifying both the power they have given us and the power they have over us, we can

assess their impact and meaning, and therefore better understand ourselves.

BREAKING DOWN THE ENCHANTMENT:

A CRITICAL AUTOETHNOGRAPHY

OF VIDEO GAMING

by

Yacine Kout

A Dissertation Submitted to

the Faculty of The Graduate School at

The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Philosophy

Greensboro

2019

Approved by

____________________

Committee Chair

©2019 Yacine Kout

ii

APPROVAL PAGE

This dissertation written by Yacine Kout has been approved by the following

committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at

Greensboro.

Committee Chair ___________________________

Leila Villaverde

Committee Members ___________________________

Kathy Hytten

___________________________

Spoma Jovanovic

___________________________

Gregory Price-Grieve

___________________________

Date of Acceptance by Committee

_________________________

Date of Final Oral Examination

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Merci à Yessica - Gracias a ti por tu amor y apoyo. I could have never done this

without you. You were there day in and day out. No one else knows the depths of my

struggles, joys, and accomplishments. You helped me lift myself up and reach this goal

when I was in the darkest pits. I am forever thankful to have you as a partner and friend.

Merci à Ulysse - You were the first to write and sketch me as “Dr. Kout.” Your

drawing has inspired me and given me courage throughout this journey. You amaze me

every day. Continue to be you, Captain Awesome.

Merci à papa et maman - Vous avez nourri un rêve d’enfant quand vous m’avez

acheté cet Amstrad CPC 464. Aujourd’hui, ce cadeau prend une tournure que je n’aurais

jamais imaginé quand j’y jouais. La graine que vous avez planté continue de porter ses

fruits.

Merci à Sabrina, Farouk, et Nabil - Je sais que je n’ai pas toujours été présent

dans votre vie à la façon dont un grand frère aurait dû l'être mais j'espère que vous verrez

dans ce projet une certaine satisfaction et peut être même une fierté.

Merci à Pierre, Vincent, Benoît, William, Johan, Vincent, Laetitia, et Moujik -

Pour ces samedis plein de possibilités, de camaraderie, de joie, et maintenant de

nostalgie. Ce sont nos amitiés que j’ai cherché à retrouver où répliquer dans les jeux en

ligne. Rien ne remplacera les histoires que nous avons créées ensemble.

Merci à tous de ne pas m’avoir inonder d’amertume quand je suis parti. J’ai mis

un océan entre nous. Il a changé nos relations et nos amitiés à jamais. Pardon. Vous me

manquez tou(te)s.

iv

To Dr. Villaverde - Thank you for guiding me on this journey. Your patience and

vigor made me a more thoughtful/mindful person and student.

To Dr. Hytten, Dr. Price-Grieve, Dr. Jovanovic - Thank you for serving on my

committee. Your feedback and encouragement helped me build myself as a more

complex scholar.

To Revital - Thank you for listening and giving an ear and heart to my immigrant

scholar dilemmas. You helped me till the very last stretch. I hope I can be as good a

friend to you as you have been to me.

To Caitlin, Oliver, Elizabeth, Cristina, Amara - Thank you my friends for

supporting me when I was stuck, for listening to my ramblings as I was making sense of

my work. I hope I was able to support you the same you did.

To Dr. Shapiro, Dr. Casey, Dr. Peck - Thank you for pushing me and supporting

me in this endeavour, whether it was by listening to my complaints, offering me

possibilities, or challenging me to write something I did not think I could do.

To Anna, Leslie - Thank you my friends for showing me that there was a joyful

end to this journey.

To Dr. Blaisdell - Thank you for showing me that I had something valuable to

bring to this world. Your genuineness and sincerity helped me start this journey.

To Kathleen - Thank you for your kindness, guidance, and support. I learned

about ELC thanks to you. You also gave me the final push I needed to get my dissertation

done in time.

v

To Stephen - Thank you for re-introducing me to philosophy and showing me that

I could be a gadfly.

To my pilot projects participants - Thank you for sharing your time and stories.

To Juan, Troy, Dawn, Emily, Chris - Your work guided me when I was incapable

of imagining my next sentence. I heard your voices as I read your introductions and

conclusions.

To my raidmates - Thank you for slaying internet dragons with me. The space we

created saved me. Looking into my experiences helped me better know myself.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................... viii

LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... ix

CHAPTER

I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................1

A Thirty-Year-Old Relationship ..................................................................1

A Cultural Phenomenon ...............................................................................3

My ActRaiser Story .....................................................................................6

From Curiosity to Fury ..............................................................................10

A Culture Shaped by Social Issues, A Force Shaping Players ..................13

Statement of the Research Problem ...........................................................15

Research Questions ....................................................................................20

Overview of the Chapters ..........................................................................21

II. BECOMING A STUDENT OF CRITICAL PEDAGOGY:

A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ON

CRITICAL PEDAGOGY .............................................................................24

Introduction ................................................................................................24

The Social World .......................................................................................26

The Question of Power ..............................................................................29

What is Knowledge? ..................................................................................32

Critical Pedagogy as Democratic Imagination: Enacting

New Futures ...........................................................................................53

Conclusion .................................................................................................58

III. AUTOETHNOGRAPHY AS METHODOLOGY ..............................................61

Introduction ................................................................................................61

Ellis’ Approaches to Autoethnographic Work ...........................................62

Doing Autoethnography: Methods and Processes in

Data Collection, Analysis, and Presentation .........................................66

Conclusion .................................................................................................90

vii

IV. BREAKING DOWN THE ENCHANTMENT:

DECONSTRUCTING A CHILDHOOD PASSION ......................................92

Introduction ................................................................................................92

Chasm Between Identities: How the Enchantment Enabled

Oppressive Forms of Play ....................................................................102

Enchanted Resistance...............................................................................143

Addressing the Enchantment ...................................................................157

Conclusion ...............................................................................................167

V. ASSEMBLING THE CRITICAL CLOCK .......................................................171

Introduction ..............................................................................................171

Identifying the Four Cogwheels...............................................................174

Conclusion ...............................................................................................201

VI. CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................203

Summary of Findings ...............................................................................203

Recommendations for Future Research ...................................................205

Implications for Practice ..........................................................................207

Limits of My Research.............................................................................209

Closing Thoughts and Questions .............................................................211

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................214

APPENDIX A. EPIPHANIES .........................................................................................239

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table 1. Key Points of Anyon’s Study on Social Class and

School Knowledge ..........................................................................................43

Table 2. Coding Data Template .........................................................................................76

Table 3. Evaluation Criteria for Qualitative Work ............................................................89

Table 4. Organization of the Chapter into Metathemes and

Subthemes ......................................................................................................100

Table 5. The Thinking/Entertainment Dichotomy ...........................................................104

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

Figure 1. A Screenshot of the Epilogue ...............................................................................8

Figure 2. Mr. Charles Class ...............................................................................................34

Figure 3. Cropped Screenshot of My Steam Library Highlights the

Categories I Had Created ..............................................................................106

Figure 4. Wildstar was a Mmorpg Set in a Futuristic Universe .......................................110

Figure 5. The Looking for a Dungeon Interface, also Known as Dungeon

Finder ............................................................................................................116

Figure 6, A Screenshot of the Recount Addon ................................................................120

Figure 7. An In-game Menu Allows Players to See All the Mounts

Available in the Game (cropped screenshot by author, 2018) ......................125

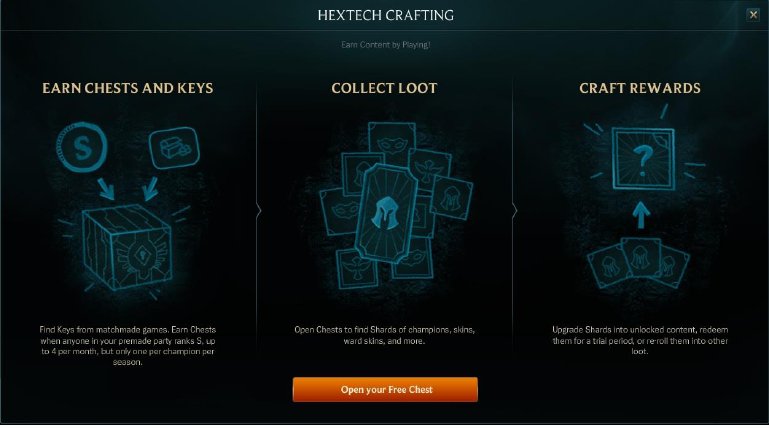

Figure 8. A Graphic Explanation of the Hextech Crafting Loot

System in LoL (Jarettjawn, 2016) ................................................................128

Figure 9. A Side by Side Comparison of the Default Brand Champion

on the Left (Plesi, 2016) and the Zombie Brand Skin on the

Right (leaguesales.com, n.d.) .......................................................................129

Figure 10. The SWL Daily Rewards Interface ................................................................131

Figure 11. A Screenshot of the “About” Section of the Official Discord

Website (Discord,2015) ..............................................................................141

Figure 12. Mysogynic Insults ..........................................................................................154

Figure 13. Braid- a Puzzle Game with 2D Platformer Elements .....................................173

Figure 14. No Pineapple Left Behind ..............................................................................179

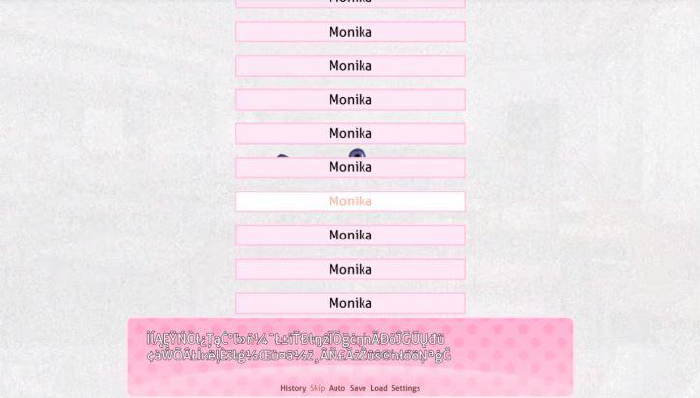

Figure 15. A Troubling Consequence of Monika’s Game Hacking

(Joshiball, 2017) ..........................................................................................183

Figure 16. On the Left, a Seemingly Bugged Version of Monika

Stands in Sayori’s Place (Joshiball, 2017) ..................................................184

x

Figure 17. A Memo Including Reflections on Creating Monsters

from Local Animals (69quato 2018)...........................................................187

Figure 18. A Boy Named Jung on an Empty Playground................................................188

Figure 19. This War of Mine – a Survival Strategy Game ..............................................192

Figure 20. Night of the Living Debt ................................................................................199

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

My project is a critical autoethnographic study on the meaning of video gaming in

my life. This project examines over thirty years of video gaming experiences through the

power of stories. My goal is to gain a better understanding of video gaming by examining

my lived experiences as a student of critical pedagogy. This project was born out of a rift

between the research on video gaming and my experiences as someone who grew up with

video games and sees in them the possibility to address injustice in our world.

A Thirty-Year-Old Relationship

Video games have been a part of my life since I was a boy. Some of my earliest

memories take me back to my vacation in my uncle’s house in Algeria. There, I would

skip trips to the beaches of Algiers to play dinosauric games with rectangles and squares

for graphics. In my middle school years in my native France, I remember staring at the

clock eager to rush to my local arcade. Sometimes I would bring a bag of chips

bolognaises to munch on in between ‘game overs.’ There, my friends and I would team

up in Double Dragon (Technos Japan, 1987) to karate kick and baseball bat our way

through waves of ‘bad guys.’ When I did not have money to play, I would head there

anyway and watch strangers play to learn from them or offer them all the wisdom an 11-

year-old player could muster. In that circle, some of my friends started calling me YAC

2

as there were only three spaces available on the high scores list. Video gaming became an

identity.

In the mid 1980’s, my parents surprised me with a gift that to this day I consider

the best present I ever received: an Amstrad CPC464. This European machine played

games by loading cassettes, a process that lasted several minutes and produced a horrible

screeching sound. It took years of saving for my parents to afford that computer. Even

though I received this cassette computer when 3½ floppy disks machines were out and

cassettes were becoming a technology of the past, this computer is one the fondest and

most significant memories of my childhood. I knew this was a financial sacrifice for them

then. This gesture is all the more meaningful now, that I too am a parent.

In my high school years, my younger brother Farouk and I created our own

competition format in Street Fighter 2 (Capcom, 1994). I had to pick every single

character available once, whereas he was free to pick whoever he wanted however many

times he wanted. That format created a handicap for me as my skill level was above his.

These days are long gone. Today, he plays in national competitions and destroys me in

every version of that game.

More than thirty years after I first slid a five franc coin into an arcade machine, I

still play video games. For example, I am a member of a megaguild, a community that

counts thousands of players who mainly play World of Warcraft (Activision Blizzard,

2004). I am also a gold ranked player in League of Legends (Riot Games, 2009) for the

second season in a row. That rank places me in the 11.66% to 37.73% percentile of

ranked accounts. I also own over 100 games in Steam (Valve Corporation, 2003), a

3

popular online “entertainment platform” where players buy games, form communities,

and share creations such as player-created levels. Many of these games I binge bought

during sales and have not had time to play. Today, some of my favorite games embed

social commentary in their narrative or gameplay. In that category, the games that

marked me include Soldats Inconnus: Mémoires de la grande guerre (Ubisoft, 2014)

which critiques war by offering different perspectives on World War I, Papo y yo

(Minority Media, 2013) which deals with child abuse, or Tacoma (Fulbright, 2017) which

addresses labor issues among many others. Video games are a passion of mine. I play

them. I make friends through them. Playing games is an important part of who I am.

A Cultural Phenomenon

At the beginning of my video gaming life, video games used to be confined to

specific spaces such as arcades, living rooms, or recess discussions. Over the last ten

years or so, video games have sprung out of these spaces. They have merged into our

everyday life. They have become a cultural phenomenon. People play on computers, cell

phones, and through Facebook. Video games have also expanded to other media,

markets, and cultural spheres. Minecraft (Mojang AB, 2011) has its own line of toys. The

Tomb Raider series has a duo of high caliber Hollywood movies starring Angelina Jolie

(Baird & West, 2001; Heath-Smith & de Bont, 2003) and another Tomb Raider movie

released in 2018 (Crevello & Uthoag). The Angry Birds series has an animated feature

movie (Hed, Maisel, Kaytis & Reilly, 2016) and a TV series focusing on The Secret

World Legends is in development (Fahey, 2017). Players of every age wear clothing

4

emblazoned with video game characters or logos such as Link (Nintendo, 1987) or

Freddy Fazbear (Cawthon, 2013).

In addition to the sprawl of video games into other media and markets, the video

gaming culture has also provided a conduit for other enterprises to make money and

increase their visibility. Toys like Barbie and comic book heroes such as Spiderman have

their own video games or video game series. The military, both the US Army (United

States Army, 2002) and the British army (Publicis, 2009), have developed video games

for military recruitment. Corporations have introduced advertisements within games,

such as Chevrolet ads on the sidelines of the FIFA 17 soccer game (EA Vancouver,

2017). Many industries and enterprises have taken advantage of the video game

phenomenon and thus they have further contributed to its expansion and normalization.

The sphere of e-sports, video game competitions, is also on the rise. In 2014,

more viewers watched the world finals of the League of Legends championship than the

NBA finals (Dorsey, 2014). In Asia, e-sports have been popular for years. There, some

players make a living out of winning. Faker, one of the most famous League of Legends

competitor, has earned over $1 million dollar in 4 years (Grubb, 2017). In the USA,

e-sports is still catching up to this level of popularity, but collegiate e-sports is gaining

steam. Several game companies have created collegiate championships. My very own

school, UNCG, placed second nationally in the World of Warcraft Great Collegiate

Dungeon Race (Blizzard Entertainment, 2017). Some schools, such as Robert Morris

University, even offer scholarships to attract video game players (Touchberry, 2017).

5

Video games have become unavoidable. The video game culture has spread to

many facets of our lives. It continues to sprawl. Video games are played by people of all

ages, 27% of all players are over 50 years old, and the distribution by gender shows a

quasi-even number of male and female players, 56% for the former and 44% for the latter

(Entertainment Software Association, 2015). In a world where video games have had

such a cultural impact, studying them and their impact is primordial. As someone who

has grown up with this medium, I feel a responsibility to make a contribution in regard to

the study and understanding of what Giroux (2013) calls the “screen culture” (p.179).

After a few years in my doctoral program, I dedicated myself to the study of video

games through critical pedagogy. Apple, Au & Godin (2011) summarize the goals of

critical pedagogy as broadly seeking “to expose how relations of power and inequality

(social, cultural, economic) in their myriad forms of combinations, and complexities are

manifest and are challenged in the formal and informal education of children and adults”

(p.3). Critical pedagogy has provided me with a theory to make sense of my life,

including video games, in a new and empowering way. It gave me a sense of agency and

the desire to study a culture I am a member of. I saw in the questioning and analysis of

my experiences the possibility to use video games to question power and make our world

a better place. I now share a thirty-year-old story that embodies the power video games

have had in my life and how I reinterpreted that story a couple of years ago through

critical questioning.

6

My ActRaiser Story

We’re in 1990 at my parents’ house. I am in my room ready to roll. I put the

cartridge in. The game loads quickly. Control pad in hand. I am set for a challenge.

“Ok, let’s play this.” I press start. “Alright, what’s this one about?” I speed read

through the scrolling introductory text eager to start hacking and slashing: This world is

in disarray. Bla bla bla. Monsters and demons roam these lands. Bla bla bla. humans

need a savior. They call upon ‘you’, a minor deity to rescue them.

“A minor deity? I guess that’s all they could muster. Sure, I can do that.” And so

it started. Hours of fighting followed. As I took the minor deity through the levels, it grew

in power. After the first city was founded, I was able to call upon magical fires, then

came thunder bolts and fire breath. The stage was set. I needed more victories, more

believers, and more power ups to defeat the Evil forces that plagued these lands. With

each freed region, more humans believed. With each new temple, more worshippers sang

the praises of their savior.

ActRaiser (Quintet Co., Ltd, 1990) was a good game. It was entertaining without

being a blockbuster. It offered a mix of genres. One level was about hacking and

slashing, imagine Mario with a sword and spells. The next level was a city managing

game, think about simcity, a simulation in which you can place buildings and create a

town. Basically, I spent one level dispatching demons clearing a piece of land, and then

the next level was about managing that land in order to grow a city and help humans

settle.

7

Towards the end of the game, my character had become a powerful deity. Many

humans believed in it. All along they had erected statues in its image and built kingdoms

in its name. After hours of play the time for the final fight had come. That boss, the

scourge of humanity, did not leave a particular mark on me. Defeating it was no

challenge. I had finally saved humans. Their world was free of all they feared. My

character headed back to the capital, head high, chest out, ready for glory. I thought I

had won.

As in many games of the early 90's, the ending sequence offered a series of

scrolling texts and short scenes during which I, the player, was limited to reading and

watching the epilogue.

My character triumphantly marched back to his city. I thought I knew what was

coming. I imagined lines of radiant people dancing throughout the streets. Joyful kids on

the shoulders of their celebrating parents. Colorful petals falling from the bluest sky.

Well, the deity was not ready for what was coming and neither was I.

Deserted streets. No song. No praises. Not a soul. Nothing. The deity wandered

through the streets. He entered the main temple where humans had placed a colossal

statue in His name. That space was now empty. The statue was gone.

The narrator, who was wrapping up the story, explained that because their world

was now empty of evil, humans no longer had a reason to worship. Therefore,

my character who had become a powerful god found himself abandoned. Forgotten, he

became dormant.

8

Figure 1. A Screenshot of the Epilogue

A screenshot

of the epilogue. The

space where

worshippers had

built a statue

of my character is now

empty. I interpreted it

as a symbol of human’s

extinct faith.

This epilogue shattered what I used to think of as "winning the game." While the

concepts of gold and glory had never appealed to me, they constituted what I had learned

to expect from completing video games. From Super Mario Bros. (Nintendo, 1985) to

Sonic (Sega, 1991), the narrative was pretty much the same: triumph and

prestige await the player at the end of the endeavor. ActRaiser's ending was not about

that. ActRaiser's ending had a message about the meaning of faith and believing. That

message shook me. It sent my head spinning. It made me question my understanding

of religion, worship, believers, god, and gods. Questions swirled in my brain "do people

only believe when they are scared of something? If they are not afraid, do they stop

worshipping and believing? In what other ways have people used gods or religions for

their own ends? Where do gods go when they are forgotten? Who holds power in

religion?" Growing up Muslim in my native France in the 1990’s, I had just a few people

to ask these questions to, namely my parents. None of their answers satisfied my thirst.

9

I was only a teenager when I played this game but this moment has stayed with

me. The game and the reflections it triggered have impacted the ways in

which I think about religion. As a matter of fact, my playing the game, amongst many

other factors and events, has played a role - even if minor - in my decision not to follow a

religious path. ActRaiser played a role in forming my identity as a non-religious person.

After that experience, I saw myself as skeptical, which I understood as someone who had

an eye for questioning cemented truths.

Interpretation Through Torpefication: Stung by the Torpedo Fish

Decades later, as I started taking classes in my doctoral program and became

exposed to different possibilities regarding education, I asked myself another layer of

questions about the meaning and impact of my video gaming experiences. I connected

one text in particular to my ActRaiser memory. Reading Ann Diller’s concept of

torpefication helped me gain a new understanding of that memory. Diller (1998) defines

torpefication as “the shock of realizing we did not know what we thought we knew”

(1998). Torpefication is a physical reaction to the realization of our own ignorance. She

derives this term from Plato’s image of being shocked by a torpedo fish, commonly

referred to as a stingray (Plato, n.d.). Beyond the shock, being torpified “bears close

family resemblances to the ability to be awed, to be surprised, to be astonished, to be

moved in a deeply moral, or ethical, or aesthetic, or epistemological, or ontological way”

(p. 8). Diller writes that through torpefication individuals will “almost inevitably

experience perspectival shifts” (p. 8). I made sense of torpefication through my ActRaiser

experience. Back then the swirling questions in my head had disoriented me, they

10

affected me to the point where I had to seek answers. Diller qualifies this search as

becoming a “philosopher of one’s own education” (p.1). The new meaning I made of this

experience fueled my research interest. Interpreting my ActRaiser through torpefication

opened up possibilities. I want to dive deeper into the study of my video gaming

experiences to better understand that medium. I want to explore video games and their

culture to improve players’ and people’s lives. Making connections between video games

and questioning power, culture, and society brought together two of my interests and

passions. At that point, I weaved my journey into academia with video games, stories,

and critical pedagogy.

From Curiosity to Fury

Early in my research I read different theories about video gaming. While they all

contributed to a better understanding of the medium, I found that a crucial aspect of the

discussion on video gaming was absent: the core of the research did not include players’

voices. The behemoth theory of gamification exemplifies this absence. Proponents of

gamification define this theory as “the use of video game elements in non-gaming

systems to improve user experience (UX) and user engagement” (Deterding, Dixon,

Nacke, O’Hara, and Sicart, 2011, p.1). Such video game elements include points, badges,

and animations. The problem with gamification is that it reduces video games to an

appeal factor, to a shiny ‘game layer’ (McBride & Nolan, 2014, p. 596), on top of

perpetuating unexamined processes of play. Bogost captures the superficial aspect of

gamification through his own definition of the term, “gamification is marketing bullshit,

invented by consultants as a means to capture the wild, coveted beast that is videogames

11

and to domesticate it for use in the grey, hopeless wasteland of big business, where

bullshit already reigns anyway” (para.5). Bogost’s definition offers a critical perspective

on gamification. It shines light on the fact that those in power, big businesses, syphon the

image of video games to use it for their own benefit without regard for the video game

medium and its community. Gamification is not about understanding the experiences of

players in a critical way in order to rethink the world outside of gaming or imagine

different possibilities for our society. Gamification is about updating already-existing

systems without concerns for justice or the video gaming culture. Gamification is about

using games as lures to continue doing what has always been done. For example,

gamifying the classroom may mean replacing bubbling right answers on a worksheet with

clicking right answers on a colorful screen. There are no meaningful changes involved.

Through gamification, “tomorrow becomes the perpetuation of today” (Freire, 1998,

p.103). Gamification translates to a surface study of video games. It ignores social,

historical, political, and cultural forces that shape all media. In ignoring these forces,

proponents of gamification silence the experiences and voices of players. My enthusiasm

for video gaming research gave way to rage.

Duncan Andrade (2009), a scholar and high school teacher, writes about righteous

rage, a rage fueled by injustice. He explains that his students, many of whom are

underprivileged, come to his classroom angry. Rage is their emotional response to an

unjust system. As a teacher, Duncan Andrade sees his role as connecting that moral

outrage to “action aimed at resolving undeserved suffering” (p.181). Stryker (1994) sees

rage as a transformative energy. She explains that “through the operation of rage, the

12

stigma itself becomes the source of transformative power” (p.249). While rage is

commonly thought about as a fire or a burning, Stryker offers a different image to capture

rage:

I am not the water-

I am the wave,

And rage

Is the force that moves me (p.247).

I make sense of my rage as a reaction to injustice. Proponents of gamification

were discarding thought provoking aspects of video games such as torpefication. By

using buzzwords such as technology, globalism, and 21st century, proponents of

gamification push for a superficial definition of education. Rather than engaging with the

electrifying power of video games, they use video games for their own ends. In throwing

away the critical power of video gaming, they were throwing away my experiences and

any other that did not fit theirs. My rage was a sign of injustice toward schooling

practices that remained unchanged, toward the portrayal of video games as mere

entertainment, and toward the discarding of my experiences. My rage moved me and

pushed me deeper into my research. Rather than a fire that spreads and consumes

everything in its wake, the wave is a movement that can’t be put out. My rage moves me

to act in the world. This project is an action against the forces that work to drain video

games out of their critical potential and demean my experiences and the experiences of

other players who have grown up with video games. This project is the wave moved by

righteous rage crashing against these forces. Through this autoethnographic study, I aim

13

to show that there are other possibilities for video gaming and education. In doing so, I

also open the door for the expression of other accounts.

A Culture Shaped by Social Issues, A Force Shaping Players

While I cherish my video gaming experiences and advocate for the use of video

gaming in teaching critical pedagogy, my project does not aim to hide or diminish major

issues in the video gaming culture. Such issues are well documented. Video games

perpetuate oppressive messages in many ways. I share a few examples below that depict

the widespread issues in the video gaming culture: the content of video games, video

gaming communities, and treating video game workers as disposable.

Oppressive Content

The 1982 video game Custer’s Revenge (Mystique) places the player in the shoes

of General Custer. General Custer, an actual historical figure, is famous for having lost a

resounding battle against Native Americans, the battle of Little Bighorn (History.com

Editors, 2009). The game, in some twisted way, aims to correct that. The goal of Custer’s

Revenge is to “navigate a battlefield to have sex with an Indian maiden (...) tied to a

post,” (Cassidy, 2002, para.1) in other words, to rape her. The 2015 game Hatred

(Destructive Creations) showcases another set of connected issues present in and

perpetuated through video games. Hatred invites players to take on the role of a mass

shooter. Creative director Jarosław Zieliński (Campbell, 2014) explains the rationale

behind the game:

The answer is simple really. We wanted to create something contrary to

prevailing standards of forcing games to be more polite or nice than they really

are or even should be. (...) Yes, putting things simply, we are developing a game

14

about killing people. But what's more important is the fact that we are honest in

our approach. Our game doesn't pretend to be anything else than what it is.

(para.7),

Through their content, Custer’s Revenge and Hatred reinforce settler colonialism, sexism,

and white supremacy. The slew of issues banalized and trivialized in these two games is

not an accident. As cultural products, video games are imbued with problematic values

that plague our world.

Oppressive Communities of Players

A set of video game players have embraced sexism and white supremacy. This

vocal group claims video gaming as their sole property and opposes any other individual

or group that claims belonging to the video gaming community. One of the most glaring

examples is #gamergate (Griggs, 2014), an internet movement which started with

targeting one female video game developer, Zoe Quinn, for what the oppressive group

referred to as the corruption of video gaming by female developers (Heron, Belford &

Goker, 2014). This movement and its actions then spread to harassing or doxxing any

woman defending or connected to Quinn.

Oppressive Companies

Issues in the video gaming culture also affect video game workers. They are

treated as a disposable workforce, who is overworked (Fuller, 2017), and for whom

overtime is not always paid (Weinberger, 2016). Issues in the culture of these companies

do not stop there. A recent report on the culture of Riot Games (D’Anastasio, 2018),

developer of League of Legends, one of the most popular games in the world, shows that

sexism is an integral part of the company’s “bro-culture” (para. 5) One of Riot games’

15

values and motto is “default to trust”—in other words, assume that your colleagues

always have good intentions” (para. 61). A former Riot Games employee shared that she

was met with criticism when explaining to male coworkers “why words like “bitch” and

“pussy” were gendered insults” (para. 60). She was told she was not abiding by the

company’s motto and culture of “defaulting to trust.” She was expected to trust that her

co-workers were not using these words as insults. Sexism and neoliberalism are alive and

well in the video gaming culture.

My goal is not to demean or ignore these issues. By looking for video gaming

elements that lend themselves to teaching critical pedagogy, I do not mean to reduce

video games to that aspect. However, as someone who has grown up with this medium, I

have experienced questioning and shifts in my thinking that I want to investigate because

they are seldom represented in the literature in education and video gaming. This does

not erase the multitude of issues tied to video gaming. Moreover, I account for these

issues in my findings chapter where I question and weigh my role in perpetuating these

forms of oppression.

Statement of the Research Problem

(...) for me, someone who the world viewed as male, World of Warcraft provided

a space to discover that I felt more comfortable when treated as female. (Dale,

2014, para 1)

People play video games for diverse reasons. Players such as Dale see in video

games, and World of Warcraft in particular, a space in which she can be herself. Making

sense of what video games bring to their players is intimately linked to their identities,

16

and to their lives outside of the games they play. Golub (2010) writes that to fully grasp

the reach and power of video games we must, as first suggested by Dibbell and Schutz,

study video games, not as an isolated space, but as an integrant part of players’ lives

(p.40). One of his main suggestions in order to conduct anthropological studies of video

gaming is to “follow participants (...) across all segments of their life-worlds that are

central to their biographies, not merely those that are virtual“ (p.40). Golub shatters the

cliché of online and offline lives as fragmented worlds by demonstrating that these spaces

are intertwined; they inform and influence each other. Gaming does not exist in a

vacuum. Video games cannot be understood as geographical spaces, to be fully

understood they must be studied as cultural spaces (p.41).

Early sociological and anthropological studies of video gaming focused on

ethnographic studies of players’ in-game experiences (Chen, 2009; Nardi, 2010). Golub’s

call highlights the necessity to study players across all facets of their lives to better

understand the meaning they draw from video gaming. To achieve this, we need to

explore the diversity of stories behind players’ gaming experiences. We need to ask who

the players are, why they choose to play the games they play, and what they get from

them. We can only achieve this by diving into players’ intimacy. The goal is not to define

the video gaming experience as a monochrome monolith, but rather to explore its

complexity and meaning by studying diverse players across gender, race, ability, and

other identity markers. My study is one slice of that larger project.

Some scholars have recently started this work by studying video gaming through

the lens of feminism (Chess & Shaw, 2015; Lavigne, 2015; Shaw, 2015) and race (Gray,

17

2014). One of their findings is that, like “any identity, being a gamer intersects with other

identities and is experienced in relation to different social contexts” (Shaw, 2012, p.29).

This statement further stresses the importance of studying video gaming beyond the

pixels on the screen. My study takes up Chess and Shaw’s (2015) call ”for other gaming

cultures and increased diversity” (p.217) by examining my lived video gaming

experiences as a student of critical pedagogy who has grown up with video games.

Hock-Koon (2011) writes that we stand at a new time in video game scholarship,

a time in which people who have grown up with video games are now entering academia.

There is indeed a growing number of video game players in academia who have

conducted research in their culture (Blackmon & Terrell, 2007; Braithwaite, 2015;

Campbell & Grieve, 2014; Chen, 2009; Gray, 2014). However, video game

players/scholars have seldom written about their own lived experiences.

Autoethnographies are rare. I have found a mere three texts that are referred to as

autoethnographies. In the earliest one, Sudnow (1983) writes about his experiences of

coming to video gaming as an adult. Throughout his work, he draws on his background

and identity as piano player to make sense of his video gaming experiences. My project

builds on his work by bringing in a different perspective on video gaming through my

identities as an immigrant, a non-Muslim Arab, and other factors that vary from

Sudnow’s identities. For example, there was no internet at the time of Sudnow’s study

and therefore no online video games. Video gaming then is not video gaming now. That

difference alone is worthy of prompting another autoethnographic study on video

gaming.

18

Bissell (2011) also wrote about his own experiences playing video games. He

describes his experiences playing video games through two interlocked entry points. The

first is his own lived experiences playing video games. The second entry point is his

interviewing of game designers such as Cliff Bleszinski of Epic Games and Jonathan

Blow, an independent designer. He uses these interviews to voice his own experiences

and reflect on them.

My project differs from Bissell’s in many ways. While I grew up on a mix of

computer and console games, I have not owned a console in over twenty years. Bissell

solely plays console games. He is not a PC gamer. While some games are available on

both format, PC and console platforms offer different possibilities for players such as

modding, the possibility for PC players to modify components of their game. My study

will add another layer of complexity to the scholarship on video gaming by bringing an

autoethnographic account of PC games, especially World of Warcraft. This is also

another major difference with Bissell’s experience. He describes WoW as “less a video

game than a digital board game” and a game he “very much dislikes” (p.40). WoW has

rhythmed my life since I started playing it in 2007. WoW has been the main game I have

played for over 10 years. While WoW is my main game, it is not the only one I play. Like

Bissell who describes GTA IV (Rockstar North, 2008) as his favorite game, having a

main game does not necessarily mean we do not play other ones. My study will cover

several games, many of which I played decades before the release of WoW and others

during the time I played WoW.

19

Chen’s (2012) study is the third piece that is referred to as an autoethnography of

video gaming. While Chen’s work revolves around his experience as a WoW player, he

centered his research on his raiding team and set the scope of his study to in-game

interactions solely within WoW. While some see his work as autoethnographic, Chen

instead describes it as “following the tradition of online games ethnography” (p.159). As

a matter of fact, he dedicates a mere seven page “mini chapter” (p.159) to the tensions

between his identities as a researcher, gamer, and educator. He discusses these tensions

within the boundaries of in-game interactions with his raidmates and does not extend his

reflections beyond this scope. The confinement of his identities to this short section

shows that, while his experiences as a raider played a role in his study, they did not

constitute the core of it. I do not label his work as autoethnographic, this does not

undercut in any ways the value of his study. As a matter of fact, his work has served to

inspire mine.

The specificities and intersections of my identities (immigrant, father, and all

other facets of my being) will be central to my work. These identities are either not

shared or not foregrounded in Sudnow’s, Bissell’s, or Chen’s work. Moreover, the scope

of my work in terms of time length (I cover the thirty plus years I have been playing) and

reach of the observation field (my lived experiences expand beyond the pixels on the

screen) are unique to my study. Therefore, my methodology for this project adds another

layer of complexity to the video gaming scholarship.

The goal of my research is to better understand the video game culture and tap

into it to offer critical possibilities for our world. I have found in my experiences ways to

20

make our world a more just place. I was also mindful that my relationship with video

games put me in a position where I had to account for problems and critiques of a

medium that contains and propagates a multitude of messages, some, if not many,

harmful. The chronological component in my study was important. I investigated how my

becoming a student of critical pedagogy shaped my lived video gaming experiences. I

wanted to know to which extent my lived video gaming experiences were informed by

critical pedagogy. I wanted to investigate my reflections, actions, and silences as I played

and navigated video gaming in and off the screen. This study represents an important

contribution to a larger whole, one voice in a larger discussion. My study is also cathartic

as I told and analyzed my stories of video gaming. By examining my stories, I am giving

them visibility, in doing so I worked to legitimize and validate my experiences.

Research Questions

In this study, I used autoethnographic research methods to explore what video

games mean to me and what they have contributed to in my life. I researched my own

experiences as a video gamer player whose identity as a student of critical pedagogy has

triggered questions and inquiries. As a student of critical pedagogy, I understand that the

relationship between players and video games is dynamic, fluid, and reciprocal. The

following questions guided my research:

1. How do I navigate the video gaming culture as a student of critical pedagogy?

2. In what ways do video games lend themselves to the teaching of critical pedagogy?

21

Overview of the Chapters

Chapter one is an introduction to this study. In chapter two, I show how gaining

the identity of student of critical pedagogy has helped me examine my schooling and

educational experiences. I did so by reviewing the literature on critical pedagogy and

drawing on my own stories of schooling. I use Freire’s (2009) concept of the ‘banking

system,’ a concept of education in which “knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who

consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing”

(p.72). These stories rely on my experiences as an Arab student in the French public

school system, the country where I grew up. I used the lens of critical pedagogy to move

from a naïve understanding (Freire, 2009), of my schooling and educational experiences

to a more complex and systemic understanding of these experiences. This chapter also

acts as a blueprint for the examination of my video gaming experiences through the lens

of critical pedagogy.

In chapter three, I go over the methodology I employed for this project:

autoethnography. I start by describing the different types of autoethnography and

explaining the specificities of personal narrative and reflexive ethnography, the two types

I employed. I then described my methods of data collection, the writing of epiphanies by

using writing as a form of inquiry, and a documentation of my current video gaming

experiences through field notes and journaling. I close this chapter by writing about the

validity of my methodology, a method that is still controversial for proponents of

canonical research.

22

Chapter four answers my first research question: How do I navigate the video

gaming culture as a student of critical pedagogy. I drew on the analysis of my epiphanies,

field notes, and journaling to establish meaningful themes. I had initially thought of

presenting my findings in two themes: the ways I consent to oppressive forces in the

video gaming culture and the ways I resist these forces. However, this study exposed a

rift in how I thought of myself and how I acted in my video gaming experiences. I

unveiled a chasm between my identity as a video game player and that of student of

critical pedagogy during my journaling and field noting. I use the concept of enchantment

to describe how my previously unexamined experiences worked to blind me to the

multiple issues I engaged with. To do justice to the movement triggered by this study, I

present my findings to my first research question in a dynamic format. I first share the

ways in which I consented to the oppressive culture of video gaming. I then expose the

ways in which I thought I resisted these forces. I conclude this chapter by wording how,

after exposing the enchantment, I worked to reconcile the two identities at the core of this

project: student of critical pedagogy and video game player.

In chapter five, I answer my second research question: In what ways do video

games lend themselves to the teaching of critical pedagogy. I use the concept of

dismantling the clock to explain how this study worked as the careful examination of my

experiences. Through the work of clockmaker, I identified four cogwheels that lend

themselves to the teaching of critical pedagogy. This chapter is my re-assemblage of

these cogwheels in alignment with critical pedagogy.

23

I conclude this dissertation in my sixth chapter. I start by summarizing my findings. I

include recommendations for future research and implications for practice. I end this

chapter and my work by sharing the limits of this study and my closing thoughts.

24

CHAPTER II

BECOMING A STUDENT OF CRITICAL PEDAGOGY:A REVIEW OF THE

LITERATURE ON CRITICAL PEDAGOGY

Introduction

Becoming a student of critical pedagogy has triggered, informed, and shaped the

questioning of my life starting with my schooling experiences and expanding to other

experiences such as my video gaming. This process has introduced questions that have

troubled my identities, experiences, and ways of seeing and being in the world. In this

chapter I write about becoming a student of critical pedagogy through the review of the

literature on critical pedagogy. Kincheloe (2008) writes that “all descriptions of critical

pedagogy—like knowledge in general—are shaped by those who devise them and the

values they hold” (p.5). Drawing a cemented picture of critical pedagogy is impossible.

Definitions are imprinted with the author’s experiences. Therefore, my understanding of

critical pedagogy will share common points with my readers’ understanding. It may also

differ on other points.

I write about my becoming a student of critical pedagogy by weaving scholarship

and my stories of schooling. My goal is to translate my journey into critical pedagogy

through pivotal stories that I interpret or reinterpret through scholarship. My stories serve

two purposes. The first is to “infuse writing with an intimacy that often is not there when

there is just plain theory” (hooks, 2010, p.50). I create this intimacy by crafting stories of

25

my schooling experience. I invite you into my world by wording it (Rose as cited in

Denzin & Lincoln, 2003).

The second purpose in using stories is to use storytelling and critical pedagogy as

a form of healing. Some of the stories I share translate difficult moments that have hurt

and shaped me as a child and continue to influence me as an adult. I use stories to show

how the critical writing of these stories serves as a “therapeutic” tool (Poulos, 2010,

p.76). I write these stories by relying on the works of critical pedagogues who have

influenced me in this critical journey. These include Paulo Freire, Henry Giroux, and bell

hooks. I braid their work around my stories. Doing so has allowed me to become a

student of critical scholarship. It helped me move from understanding my experiences as

solely saying something about me and my worth or unworthiness to understanding the

social, cultural, and political backdrop that shaped these experiences. This critical

understanding has empowered me to address these issues.

Through this chapter, I am laying the ground for writing and reinterpreting my

stories of video gaming through the lens of critical pedagogy. This chapter shows how

gaining the identity of student of critical pedagogy has helped me examine important

moments of my schooling and education. In this review of critical pedagogy, I show how

making sense of these experiences through critical pedagogy has opened a space for me

to act in the name of creating a more just world. By making sense of critical pedagogy

through my schooling experiences and describing the ensuing movements in my thinking,

I set the grounds for examining my video gaming experience and exposing the

movements that resulted from this study.

26

The Social World

Left. Right. Left. Right. Left. Right.

Shining black shoes stomp their path in flawless rhythm.

Left. Right. Left. Right. Left. Right.

The military parade is on. The symbol, the blazon of a country.

Left. Right. Left. Right. Left. Right.

Stop.

Uniformed and perfectly groomed, they swing their weapons to their other flank.

Go.

Left. Right. Left. Right. Left. Right.

Wooden weapons. Real pride. ROTC teenagers. Real military hunger.

I was an ESOL teacher when I first set foot on the campus of an American high

school. I was shocked to see a group of fourteen-year-olds in military uniforms ordered

around by a slightly less young leader in that space. This was an aberration. Military

education in a high school does not exist in France. I asked my fellow teachers about

what I was witnessing. It took a discussion for me to understand that ROTC was an actual

school program, that it was present in most high schools across the country, that

militarizing youth minds was a state sponsored goal. This moment sent me in a spin. The

only countries I knew of with such programs were totalitarian regimes which

indoctrinated youths. There, the young were portrayed as disposable. A strong sense of

honor shaped by powerful autocrats was instilled in these young minds in order to

legitimize sending their bodies to war. The message I had learned in France was that

youth in the military is an antidemocratic sign.

The surprise did not stop there. What I understood as a clash between democratic

ideals and military presence in schools was seen as ‘normal’ by my coworkers. It made

sense to them. “This is just how we do things” (p.19). Schwalbe (2007) uses this sentence

27

to translate how decisions made by those shape our society become invisible. With time

these decisions become habits. In turn, these habits become norms and part of our belief

system. We accept them without questioning them. This “consent” is “given by the great

masses of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant

fundamental group” (Gramsci, 1971, p.12). My coworkers saw state sponsored military

education as ‘natural’ as the air they breathe. This is what Schwalbe describes as the

social world. A world shaped by people in power. A social construction in which the

builders and their intent disappear from public sight, from public debate, for public

thought. ROTC programs do more than normalize the presence of the military in schools,

they play a part in normalizing militarization in all facets of American society. I came to

recognize that students in the ROTC program do learn about leadership and a certain idea

of service. But this program cannot be detached from the impact the normalization of

militarization does on a national and international level.

For me, a French citizen, someone who has been socialized differently, aspects of

the American culture that clash with my own stand out. I noticed other instances of the

normalization of the military in the US. Take the case of November 11th. In the United

States, this holiday celebrates veterans, people who have risked their lives in wars. In

France, on that same day, France commemorates the end of World War I. While subtle,

the differences between these two messages are meaningful. Celebrating the people who

fought contributes to honoring and elevating the image of warriors in terms of honor,

pride, and sacrifice. Commemorating the end of a war sends a different message about

war: that it needs to stop. Such educational messages, whether they take place in schools

28

or not helped me understand why the US military budget is larger than that of China,

Saudi Arabia, Russia, United Kingdom, India, France, Germany, and Japan combined

(U.S. defense spending compared to other countries, 2017). All these messages contribute

and reinforce the will of those in power, their desire to have a military force handy to

serve their purpose.

Writing about the ROTC experience helped me identify the invisible messages

that establish the place of the military in American culture. By reflecting on these

experiences, I came to understand essential social rules that regimented the country

where I now live and the one I grew up in. Witnessing the marching of youth in schools

was not the result of purchasing uniforms and slapping them on teenagers. The overlap

between public schooling and the military is the result of shared beliefs (Schwalbe, 2007,

p.15). The world we inhabit is not merely made of atoms and molecules. Rules that made

possible the presence of the military in schools and therefore the importance of the

military in US society correspond to the ideas and ideals of people who can make such

rules. In turn, these systems and rules come to shape the beliefs of the larger public. The

power to shape the rules gives the possibility of those who hold such power to create

schools and societies that reinforce their ideas and ideals. With time, these decisions

become shared belief, become the norm, and become invisible even to those who did not

play a role or have a voice in bringing these rules into existence. This is the case even

when these rules and systems go against the interests of those who believe in them.

Gramsci (1971) uses the term “hegemony” (p.12) to describe the domination of one

group above others. Dominant groups achieve hegemony through either consent or

29

coercion to legitimate ‘common sense,’ a social, cultural, and economic order of the

world that benefits the dominant group. What holds this social construction together is

not the asphalt of our roads or the cement of our buildings. It is the invisibility of the

ideas that compose it. All societies are built on ideas that become norms. No social

system can exist without them (Johnson, 2014). Because I was brought up in a different

country with different norms and habits, American norms and habits that differ from

mine stand out like a sore thumb. My ROTC experience triggered questions. Learning

about critical pedagogy gave me vocabulary to identify power and question its use in

shaping schools, education, and our world.

The Question of Power

Neutral, objective education is an oxymoron. Education cannot exist outside of

relations of power, values, and politic (Giroux, 2013, p.192)

My journey into critical pedagogy has exposed many of the messages I grew up

with as mirages. “There is no place for politics in schools” is a message I heard from

teachers, parents, administrators, friends, and media. Education was presented to me as a

golden ticket to lift myself up, the guarantee of a bright future. My parents, immigrants

from Algeria, taught me that degrees would allow me to access a stable life. They talked

about schools, grades, and diplomas as noble, essential, and a representation of my

intelligence, of my worth. While degrees offer many advantages, such as better chances

of finding a job and ensuring a stable economic future, this message is incomplete and

works to hide the power and politics behind schools and education. My parents

participated in spreading this message, not because they were in on it, but because this is

30

how the world, the social world had been presented to them. Without critical ways of

seeing the world they were not able to challenge that message.

Through becoming a student of critical pedagogy, I have reinterpreted my stories

of schooling and education to expose themes of domination that run through the history

of schooling such as “school as managers of public thought” or “schools as engines of a

consumer society” (Spring, 2011). Giroux writes that there is no such thing as neutral

education, that the decisions that shape schools are a reflection of politics, values, and

power. Critical pedagogy gave me the language to understand school and the world as a

social construction, as shaped by people with power. Becoming a student of critical

pedagogy has granted me knowledge, language, and questions to expose incomplete

and/or hurtful surface messages I had been bombarded with. The questioning of the social

world has helped me understand that my schooling experiences were not neutral, that

they were shaped by many unseen forces (Kincheloe, 2008, p.71). This questioning

should not be understood as the demonizing of schools. As a student of critical pedagogy,

I see in education and schools a tool to promote democratic values and democratization,

that is to create a society that is fair and just and that allows everyone to live free, full,

and dignified life (Schwalbe, 2007; Shapiro, 2005). As my ROTC story highlights,

questioning power is essential in assessing whether schooling is indeed contributing to

the creation of a more just world. As a student of critical pedagogy, I want to ensure that

the rules and systems in place are working for the benefit of all, not only for the few

shaping the social world.

31

Education plays a major role in shaping our shared beliefs, in shaping the social

world. One of the ways schools shape students’ understanding of the world and place in it

is through its portrayal of knowledge, the way schools teach what it means to know

something. There are two critical questions that revolve around knowledge which I will

use to anchor my becoming a student of critical pedagogy. The first is ‘what is

knowledge?’ or what does it mean to know something. The second is ‘whose knowledge

is valued and deemed valid’ and therefore whose knowledge is devalued and demeaned. I

tackle these questions separately in the next section by relying on Freire’s (2009) concept

of the ‘banking system’ (p.72), a system Freire exposes as harmful to democratic values

in which knowledge is depicted as passive, detached, and hermetic. Through the banking

process, the world is presented as static, a world in which students have no say, instead of

a social construction, a world in which students have power. Through the banking

process, the social construction of the world is hidden. Ideas and systems that are harmful

become difficult to see, challenge, and change. Therefore, the social world and any

injustice it harbors continue to exist. It is in the democratic hope of exposing these

injustices that I take on these questions of knowledge. I do so by sharing stories of my

schooling experiences that conveyed harmful messages and hurt my sense of agency and

identity. I show how critical pedagogy has helped me reinterpret these stories in the

larger context of power and politics.

32

What is Knowledge?

What It Means to Learn in Mr. Charles 7th Grade History Class

Mr. Charles: “Title in red. Centered. Write bla bla bla.”

As instructed, I take my red pen and write that exact title as neatly as possible. A

perfectly written B, then comes an L, and an A. I write the next two words with the same

attention. Mr. Charles will pick up our textbooks and check colors and formats as he does

every week. I know my parents will get mad if any teacher says anything negative about

my work. And so I pen the title with great focus and a tint of fear.

Mr. Charles: “Now, green pen for the first level subheading. No indentation.

Write bla bla bla.” I switch pens and continue working. I want to take my time to write

clearly. My sixth grade French teacher had told me that my handwriting was poor. She

instructed me to stop writing in cursive and only write in print. This, she said, would help

me form better looking letters even if it took me longer to write. I look around to make

sure that I am not falling behind. The other students might be faster than me. Writing in

cursive is the norm in French schools. I am the only one person I know who writes in

print.

Mr. Charles: “Now, black pen for the second level subheading. It must be

indented by 3 centimeters. Write bla bla bla.” The monotony of copying titles is

rhythmed? by the mechanical act of switching of pens. This pseudo-physical activity is

the only thing that keeps me and many of my classmates from falling asleep in this

history/geography combo class. Cemented behind his desk, Mr. Charles moves on to

dictating his notes for that subsection. Blue. Copying notes has to be done in blue. I focus

33

on Mr. Charles’ voice and write the words as I hear them. I stay silent. No one ever says a

word in history/geography class. In between our note copying, one of us may be called to

the board to point at an answer on the giant map. Stepping up to the front of the class was

terrifying. We preferred to stay invisible.

I did not think of Mr. Charles as a mean teacher and despite the rigor and

extensiveness of the note copying, I did not think of him as a strict teacher either. During

recess, the words we used to describe him and his class were boring, low energy,

annoying, and soporific. On test days, these words echoed with bitterness and irritation…

----------------------------------------

What was the second subheading again? Why can’t I remember? I did study

yesterday. I always learn these lessons by heart. I am a good student. I make very good

grades no matter the class. Why doesn’t that subheading come back to me? I read over

the first subsection of notes I spat back out word for word hoping it will lead me to

figuring out what that second subheading is.

34

Figure 2. Mr. Charles Class

Yacine Kout

19 septembre 1989

Contrôle d’histoire

Question: What is Bla bla bla?

Bla bla bla

Bla bla bla bla bla bla

Bla bla bla bla bla bla

Bla bla bla bla bla bla. Bla bla bla bla bla bla Bla. bla bla bla bla bla.

Bla bla bla bla bla bla. Bla bla bla bla bla bla. Bla bla bla bla bla bla.

Bla bla bla bla bla bla.

??? ??? ??? ??? ??? ???

No. It’s not coming back. What’s going to happen if I don’t make a good grade? I

better not think about that. Just read it again Yacine. It’s bound to come back... eventually

*gulp.* I look around. Everybody else has their nose buried in their sheet of paper.

What’s happening? Slimane had told me that sooner or later the streak of great grades

would end. “20/20’s belong in elementary school,” he said. Seventh grade is a different

story. The words and sentences I cannot remember, those I was to write on my test, are

now goosebumps on my skin. If I get a bad grade the glasses on my nose will no longer

be seen as the mark of my so-called intelligence. Instead, they will paint me as a good for

35

nothing, someone who can’t play sports and who isn’t even good at school. I am

overwhelmed with shame and fear. There is no room for bad grades at home.

Making Sense of Mr. Charles’ Teaching: Banking System and Schooling.

My experience in Mr. Charles’ class is not an anomaly. This experience

represents what many have come to think of as learning: absorbing facts detached from

our lives and spitting them back out in the same way they were thrown at us. In the USA,

this is usually done by finding and bubbling the right answer. While I never had to bubble

answers on a test (multiple choice tests did not exist when I was schooled in my native

France), many of my tests required me to write word for word or paraphrase what I was

dictated in class. Like hooks (2010), I found that many of my classes were “a

dehumanizing space” (p.34), a space where my thoughts and questions were not

welcome. This model of learning constitutes the norm in the USA. People in and out of

schools have come to see this way of learning as the only way of learning. Freire (2009)

coins that system the ‘banking system’ (p.72).

The banking system. In my middle school, Mr. Charles’ class and other classes

like his were notorious for the pain they inflicted on their students. We, the students, were

seen as empty objects who had nothing to bring to the class. We were treated as ignorant,

knowledgeable only if we followed directions, applied the colored template mindlessly,

copied notes religiously, and regurgitated them verbatim. Mr. Charles’ class stood out

among other classes in which the teacher adopted the banking concept of education

because it was the first one in which the entire 55 minutes were spent on listening to his

words and copying them according to a strict color coding. Another telling memory of

36

that class is that of my friend Jérôme. He would secretly record Mr. Charles’ lecture on

his mini-cassette recorder. On test days, he would slyly run the earphone cable through

his sleeve right before class. During the test, he would play the recorder in his pocket and

find the portion of the recording that corresponded to that test’s lesson. In banking,

learning is synonymous with repeating. Students’ thoughts, experiences, and questions

are erased from the learning process. Jérôme’s body was a mere conduit for Mr. Charles’

words. Jérôme was absent from his test as we were absent from that class. Getting good

grades in Mr. Charles’ class and in the banking system is a reward for complying with a

system that objectifies and silences students.

In the banking system, schools are modeled after the factory model. The teacher is

the factory worker. The students are the inanimate products built by the teacher. The

setup of the classroom, lines of desks facing the all-knowing teacher, reinforces the

centrality of the teacher’s knowledge and reciprocally the ignorance of the students. In

Mr. Charles’ classroom, all the desks were facing him. He was the center of the attention,

the center of teaching. This layout reinforced the idea that learning was a transaction that

originates from the teacher and goes toward the students. Freire (2009) states that “in the

banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider

themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing” (p.72).

Through this idea, students adopt an inanimate state which equates them to empty

inanimate vessels. The act of teaching translates to the teacher “depositing” their

knowledge into “depositories,” passive students who are reduced to objects (Freire, 2009,

p.72). The finalization of the learning transaction in Mr. Charles’ class occurred during

37

tests when students were to present him with his own words, organized in the same way

he introduced them to us, using the same color coding he ruled his class through. In

schooling, conforming is key. Students are labeled as ‘educated’ only after they can

replicate what they are told and shown. As Freire (1998) writes, “there is no education

here. Only domestication” (p.57).

Invisible messages such as the place of students in the classroom, the

unworthiness of their experiences, and their absence in the learning process are referred

to as the “hidden curriculum.’ Vallance (2006) writes that the “the functions of this

hidden curriculum have been variously identified as the inculcation of values, political

socialization, training in obedience and docility, the perpetuation of traditional class

structure - functions that may be characterized generally as social control” (p.79). These

are teachings that are not written in lesson plans. They correspond to teachings that