reprinted logo will go here

March 5, 2024

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg

Senator, 34

th

District

1021 O Street, Suite 6530

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Senator Umberg:

At the end of December, you requested that we examine the current and future availability of

court reporters in the trial courts and provide information no later than March 5, 2024. In

addition to any information we deem to be relevant and important, you specifically asked that we

provide data and findings in the following key areas:

• Existing policies related to the provision of court reporters across case types and

specific proceedings, including how courts are operationally making use of their

existing court reporter workforce, the extent to which electronic recording is being

utilized because court reporters are not available, and the extent to which there is a

lack of record because electronic recording is not permitted by law and a court

reporter is not available.

• Existing court reporter levels, the extent to which there is a shortage, and potential

factors contributing to a shortage.

• Future availability of court reporters, including the impact of the authorization of

voice reporting as a means of producing a verbatim record and trends related to the

number of people becoming newly certified.

• Use and impact of the additional ongoing funding provided to increase the number of

court reporters in family and civil cases.

LAO Summary. In this letter, we provide background information on court reporting, and

information on the current and future overall availability of court reporters in California, as well

as their specific availability and use in the trial courts. This includes information on how the

availability of court reporters in the trial courts has (1) affected how courts use court reporters

and electronic recording, (2) affected the production of records of proceedings, and (3) created

operational challenges for the courts. We then provide information on how much is currently

spent to support court reporter services as well as how the trial courts have made use of the

$30 million in additional General Fund support provided annually to increase the number of

official court reporters in family and civil law proceedings. In addition, we discuss how trial

courts are competing with the private sector for court reporters. Finally, we provide key

questions for legislative consideration related to the availability of court reporters. To prepare

this letter, we evaluated data collected from and/or provided by the Court Reporters Board

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 2 March 5, 2024

(CRB), Judicial Council, and trial courts, and consulted relevant papers and studies. We also

consulted with numerous key stakeholders—notably CRB, trial court administrators, and court

reporters—to obtain a diverse range of perspectives and insights.

BACKGROUND

Court Reporters Licensed by State

Court Reporters Create Records of Legal Proceedings. Court reporters create records in

court proceedings as well as non-court proceedings (such as depositions). Court reporters can be

public employees hired by the courts, private contractors who can be hired individually by the

courts or lawyers, or private employees who work for a private firm which can contract with the

courts or lawyers to provide services.

Court Reporters Licensed by State to Create Records in Different Ways. State law requires

CRB to oversee the court reporter profession. This includes the licensing of court reporters, the

registration of all entities offering court reporting services, and the enforcement of related state

laws and regulations. Prior to September 2022, court reporters were generally licensed to

produce an official verbatim record via a stenographic machine—a specialized keyboard or

typewriter used to capture their typed shorthand. These court reporters are generally known as

“stenographers.” Chapter 569 of 2022 (AB 156, Committee on Budget) authorized voice writing

as an additional valid method of creating such a record beginning September 2022 and

authorized CRB to issue licenses for court reporters—known as “voice writers”—who use voice

writing. Voice writers make verbatim records by using a machine to capture their verbal

dictation of shorthand. Court reporters can also be requested to produce transcripts. This requires

them to transcribe the shorthand records they produce into a specific written format that can be

read by untrained individuals. Chapter 569 also required that licensees—whether they produced

a record via stenography or voice writing—be treated the same by CRB and public employers.

This specifically includes prohibiting public employers from providing different compensation

purely based on the manner in which the licensee produces the record.

Court Reporters Must Qualify for and Pass a Licensing Examination. To receive a court

reporter license, individuals must pass a licensing examination, be over the age of 18, and have a

high school education or its equivalent. Individuals may qualify for the examination in various

ways, such as successfully completing a court reporting school program or having a license from

another state. In a May 2023 Occupational Analysis conducted by the Department of Consumer

Affairs (DCA), a survey of select court reporters indicated that 90 percent of licensees qualified

for the court reporter licensing examination by completing a course of study through a California

recognized court-reporting school. The court reporter licensing examination consists of three

parts: (1) a written, computer-based English grammar, punctuation, and vocabulary test; (2) a

written, computer-based professional practice test evaluating knowledge of statutory and

regulatory requirements as well as key legal and medical terminology; and (3) a practical

dictation and transcription test in which individuals must be able to transcribe a ten-minute

simulated court proceeding at 200 words per minute and with a minimum 97.5 percent accuracy

rate.

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 3 March 5, 2024

Court Reporter Licenses Valid for One Year. Court reporter licenses are valid for one year,

require the payment of an annual fee, and indicate whether licensees are certified in stenography

and/or voice writing. CRB can suspend or revoke licenses if professional standards are not met

as well as reinstate them if appropriate. Licensees who fail to pay their fees for three consecutive

years are required to retake the licensing examination. Additionally, licensees are required to

notify CRB of any name or address changes within 30 days.

Court Reporters Provide Service to Trial Courts

Records of Court Proceedings Are Important for Due Process. A record in court

proceedings is important to ensure due process. For example, a lack of a record can mean that

not all parties in a case have the same understanding of what occurred in the proceeding (such as

the specific conditions of a restraining order). It can also make it difficult for an appeal to

succeed. In addition, a record is often necessary to substantiate a claim of judicial misconduct.

This is because, without a record, it can be difficult for the Commission on Judicial

Performance—which is responsible for adjudicating claims of judicial misconduct—to

investigate and resolve such claims.

Court Reporters Required to Make Records in Certain Court Proceedings. State law

mandates court reporters prepare official verbatim records of certain court proceedings. This

includes felony and misdemeanor, juvenile delinquency and dependency, and select civil case

proceedings. However, even in non-mandated proceedings, trial courts may choose to provide a

court reporter if one is available. If the trial courts are unable to (or choose not to) provide court

reporters in non-mandated proceedings, litigants are allowed to hire and bring their own private

court reporters to make a record of proceedings at their own expense. State law generally

requires that court reporters provided by the trial courts be present in person.

Court Reporters Paid for by Courts or Litigants Depending on Various Factors. The trial

courts bear the costs for providing court reporters in mandated proceedings and may choose to

bear the cost in cases where they elect to provide court reporter in certain non-mandated

proceedings. However, for non-mandated civil proceedings, state law generally requires a

$30 fee be charged for proceedings lasting an hour or less and that actual costs generally be

charged for proceedings lasting more than an hour. Because the actual cost is charged, the

amount paid can vary by court. Despite this general policy, trial courts are required to provide

and pay for court reporters in non-mandated civil proceeding for those individuals who request

one and are low income enough to qualify for and be granted a fee waiver by the courts (known

as Jameson cases). Court reporters separately charge courts (generally in mandated proceedings)

and litigants (generally in non-mandated proceedings) for the costs of preparing transcripts.

Electronic Recording Used in Lieu of Court Reporters in Certain Proceedings. If a court

reporter is not available, state law authorizes trial courts to use electronic recording to make a

record in infraction, misdemeanor, limited civil, and Jameson civil case proceedings. When

electronic recording is used in lieu of a court reporter, the proceedings are recorded by

equipment in the courtroom. Courts may charge a fee to provide a copy of a recording to a

litigant—typically to cover the court’s cost of providing the recording. In some cases, electronic

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 4 March 5, 2024

recordings can be used in lieu of a record produced by a court reporter. In other cases, an

electronic recording must be transcribed to produce a transcript.

OVERALL AVAILABILITY OF COURT REPORTERS IN CALIFORNIA

Current Availability of Court Reporters Declining and Geographically

Concentrated

Number of Licensed Court Reporters Declining. The number of court reporters with active

licenses has steadily declined over the last 14 years. As shown in Figure 1, the number of court

reporters with active licenses declined from 7,503 licenses in 2009-10 to 5,584 licenses in

2022-23—a decline of 1,919 licenses (26 percent). Of the 5,584 active licensees in 2022-23,

4,752 (85 percent) reported being in state and 832 (15 percent) reported being out of the state or

out of the country. (The number of active in state licensees is particularly relevant as state law

generally requires that court reporters provided by the trial courts be present in person.) We

would also note that the number of active licensees reporting being out of the state or out of the

country has increased in recent years. Specifically, 188 more active licensees reported being out

of state or out of the county in 2022-23 than in 2019-20—an increase of 29 percent.

Many Existing Court Reporters Could Be Approaching Retirement. In examining court

reporter licensee data as of January 2024, there were 5,444 active court reporter licensees—of

which 4,618 were in state and 826 were out of the state or out of the country. As shown in

Figure 2 on the next page, about two-thirds of active in-state licensees (3,115 individuals)

received their initial license prior to 2001—more than 23 years ago. Additionally, the number of

licensees receiving their initial license in recent years has declined. This suggests that the

existing court reporter licensee population is generally older and that a major share of them could

be eligible for retirement in the near future. Further supporting this conclusion, the data reflected

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 5 March 5, 2024

about 990 delinquent or expired licenses as of January 2024. As shown in Figure 3, 86 percent of

these licensees (851 individuals) received their initial license prior to 2001. This suggests that it

is possible that many of the individuals who allowed their license to become expired or go

delinquent did so due to retirement. Finally, the DCA May 2023 Occupational Analysis indicated

that about 40 percent of court reporter survey respondents self-reported being ten years or less

from retirement.

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 6 March 5, 2024

New Licenses Generally Decreasing in Years Before the Authorization of Voice Writing.

As shown in Figure 4, the number of new licenses issued by CRB has generally declined in

recent years. It is important to note, however, that this data does not reflect the time period after

the authorization of voice writing in September 2022. The number of new licenses issued has

fluctuated between 2009-10 and 2021-22—ranging from a high of 117 licenses in 2013-14 to a

low of 32 licenses in 2018-19. In the two years just prior to the authorization of voice writing,

there were relatively few new licenses. Specifically, there were 39 new licenses in 2020-21 and

35 new licenses in 2021-22, which could reflect the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Court Reporters Geographically Concentrated. As of January 2024, active licensees are

physically located in 54 out of the state’s 58 counties. Consistent with the state’s overall

population distribution, licensees tend to be geographically concentrated in certain counties.

Specifically, out of the 4,618 in-state active licensees, nearly 38 percent were located in two

counties—1,101 licensees (24 percent) in Los Angeles County and 654 licensees in Orange

County (14 percent). Another ten counties had between 100 to 355 active licensees each—

representing about 39 percent of the active licensee population. In total, this means that a little

more than three-quarters of the active in-state licensees are located in 12 counties. This is notable

as court reporters provided by the courts are generally required to appear in person at court

facilities. As such, certain courts may have more difficulty than others in meeting their need.

Future Availability of Court Reporters May Increase Due to Voice Writing

Voice Writing Could Increase Licensing Examination Passage Rates. As voice writing was

authorized as a valid method for producing a record only in September 2022, there is currently

limited data to assess its impact. However, there are some early promising signs that voice

writing could help increase the number of individuals passing the licensing examination. In

conversations with stakeholders, our understanding is that the dictation skills portion of the

licensing examination is easier to pass for voice writers than stenographers. This is because

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 7 March 5, 2024

individuals generally speak naturally at a faster rate than they can type, which can make it easier

for voice writers to complete their court reporting school programs and meet the minimum speed

and accuracy thresholds to pass the dictation portion of the exam. As shown in Figure 5, the

overall pass rate for the dictation skills portion of the court reporter examination has increased in

the two most recent tests offered in July and November 2023—the first two months in which

voice writers from court reporting school programs took the test. Specifically, the pass rate for

all test-takers increased from 29 percent in the March 2023 test to 45 percent in the November

2023 test. The idea that the overall higher passage rates in July and November 2023 are

potentially due to the high passage rates of voice writers is supported by data on dictation skills

test results for those coming out of a court reporter school program. Specifically, in looking at

the July 2023 results, voice writers (all first-time test-takers) averaged a pass rate of 50 percent

and stenographers averaged a pass rate of 23 percent. Similarly, in looking at the November

2023 results, voice writers averaged a pass rate of 73 percent and stenographers averaged a pass

rate of 13 percent.

Voice Writing Could Increase Number of Individuals Pursuing Court Reporting Careers.

In conversations with stakeholders, the seemingly higher pass rate for voice writers and the

shorter time needed to complete court reporting school programs for voice writers could result in

more people seeking to become court reporters. (As mentioned above, most individuals qualify

for the court reporting licensing examination by completing a school program.) Stakeholders

shared that court reporting schools have begun offering voice writing programs and indicated

that at least some schools now have wait lists of students. Supporting this perspective, since the

authorization of voice writing in September 2022, four out of eight registered California

reporting schools have had voice writing students from their programs taking the dictation

portion of the court reporter examination. Additionally, as of January 2024, CRB reports

30 individuals being licensed as voice writers and 4 being licensed as both stenographers and

voice writers. In addition, with shorter program lengths and higher passage rates for voice

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 8 March 5, 2024

writing, it could be fiscally beneficial for more schools to offer voice writing or for schools to

offer more slots or classes in voice writing as more students can be processed at a lower cost

compared to stenography. As such, the authorization of voice writing could help increase the

total number of active court reporter licensees in the near future.

AVAILABILITY OF COURT REPORTERS IN CALIFORNIA TRIAL COURTS

Number of Court Reporters Below Reported Need and Declining

Actual Number of Court Reporters Less Than Need Identified by Judicial Branch. Using

2022-23 data, the judicial branch indicates that 1,865.5 full-time equivalent (FTE) court reporter

staff would be needed for trial courts to provide court reporters in all proceedings—except for

infractions, misdemeanors, and limited civil proceedings in which electronic recording is

authorized. (For the purposes of counting FTEs, two half-time employees are counted as one

FTE.) This estimate was reached by assuming the courts would need 1.25 FTE court reporters

for each judicial officer. The trial courts also report that about 1,164 FTE positions (69 percent)

were filled in 2022-23—which leaves 691 FTE positions (37 percent) that the judicial branch

estimates would need to be filled to provide court reporters in all proceedings where electronic

recording is not authorized. (We note that this difference may actually be greater. After

comparing conversations with certain court administrators with data, we believe that some FTE

positions reported as filled may not actually be regularly filled. This is because some FTE

positions may have been reported as filled despite court reporters having retired or being out on

the leave for part or most of the year.) The specific need, however, varies by court. For example,

the Kings court reports having filled FTEs sufficient to meet only 15 percent of its estimated

need. In contrast, the San Mateo court reports having filled FTEs sufficient to meet 84 percent of

its estimated need. As shown in Figure 6, most courts currently have less than 80 percent of their

estimated need met.

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 9 March 5, 2024

Increased Vacancies at Courts. Through a survey we administered with nearly all trial

courts responding, trial courts have reported a marked increase in the number of court reporter

FTE vacancies they are experiencing. (We would note trial courts, in contrast to state agencies,

have greater flexibility in the creation and elimination of positions. Trial courts individually may

also treat position counts differently. As such, the actual number of vacancies could be higher or

lower than reported.) As shown in Figure 7, court reporter FTE vacancies have increased from

152 FTE positions as of July 2020 (a 10 percent vacancy rate) to 400 FTE positions as of July

2023 (a 25 percent vacancy rate). This is despite increased efforts by trial courts to actively

recruit new court reporters—including by offering significant compensation-related benefits

beginning in 2022-23. (These benefits, which are partially or fully supported by $30 million in

dedicated annual state funding, are discussed in more detail later in this letter.)

Departures Not Offset Despite Increased Hiring. While nearly all trial courts responded to

the survey we administered, not all courts were able to provide the data we requested related to

new hires and departures. The data received, however, indicate that the number of court reporter

FTEs leaving courts has not been offset by increased FTE hiring numbers. Trial courts reported

roughly between 150 to 200 departures each year between 2020-21 and 2022-23. In contrast, trial

courts reported hiring 71 new FTEs in 2020-21, which increased to 104 new FTEs in 2022-23.

However, as shown in Figure 8 on the next page, these new hires were not sufficient to replace

the departures—leading to a net loss of court reporter FTE positions—consistent with the

increased vacancies described above. The number of courts actively recruiting for new court

reporter employees also increased from 29 courts in 2020-21 to 42 courts in 2022-23—an

increase of 45 percent. Courts indicated that some common reasons for departures included

retirement, going into the private market, and resignation.

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 10 March 5, 2024

Courts Starting to Hire Voice Writers. To date, seven courts have reported hiring voice

writers. In examining data from courts that were able to provide hiring data, about 9.3 FTE out of

60.5 FTE new hires (15 percent) were voice writers. In addition, about 80 percent of trial courts

expressed no preference between court reporters creating a record via stenography versus voice

writing. The remainder who expressed a preference for stenography generally indicated that, for

most of them, the preference was due to a current lack of familiarity with voice writing. It seems

as if this can be easily overcome by demonstrations and education to make courts more

knowledgeable and confident in voice writing. This suggests the authorization of voice writing

could have a positive impact in helping the trial courts address their identified court reporter

need.

Current Availability of Court Reporters Has Impacted Courts in Various Ways

Availability of Court Reporters Has Affected How Courts Assign Court Reporters to

Proceedings. Existing trial court polices for use of court reporters varies by court based on

operational and budgetary choices, as well as on the overall availability of court reporter

employees and private court reporters. In the past, when court reporter availability was sufficient,

our understanding was that court reporters were generally assigned to a specific courtroom or

judge. Over time, due to the decline in the availability of court reporters at the trial courts, this

policy has changed. Now, some courts assign their court reporters to specific courthouse

locations, courtrooms, or calendars. Other courts place their court reporters in a pool by case type

or location and assign them out as needed. Still other courts have some court reporters that are

designated as “floaters” who are available to be assigned to any proceeding or location as

needed. Courts may also use a combination of these methods. For example, a court may assign

court reporters to criminal and juvenile courtrooms as those generally have mandated

proceedings and pool court reporters available for civil cases to assign them out for specific

proceedings that may need to be covered. Court reporters who finish their assignment earlier

than expected may then be assigned to another courtroom. Finally, trial courts may contract with

a private firm or hire private court reporter contractors to cover vacancies, scheduled or

unscheduled court reporter absences, and unexpected demand for court reporter services.

Availability of Court Reports Has Limited the Types of Proceedings Court Reporters Are

Provided in. The availability of court reporters in each trial court also shapes what types of

proceedings a court reporter may be provided for. All trial courts typically provide court reporters

in felony and juvenile proceedings as mandated by law. While court reporters are also generally

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 11 March 5, 2024

mandated in misdemeanor proceedings, some courts use electronic recording in these proceedings

when a court reporter is not available as allowed by law (this is discussed in greater detail below).

Courts generally do not provide court reporters in infraction cases. There are more significant

differences in civil case types—including general civil, family, probate, and mental health

proceedings. While a select number of civil proceedings are required to be covered by a court

reporter, trial courts have more discretion in whether other civil proceedings are covered. This

leads to more significant differences between trial courts. For example, courts differ in whether

court reporters are provided in restraining order proceedings and conservatorship proceedings.

However, over time, courts have slowly withdrawn court reporters from various civil proceedings.

For example, the Santa Cruz court stopped regularly providing court reporters in probate cases in

2018, in Department of Child Support Services proceedings in 2021, and civil and family

restraining orders in 2023. Most courts currently do not provide court reporters in non-mandated

civil proceedings, but may attempt to do so if court reporter resources are available. For example,

one court reported attempting to ensure a court reporter was available to cover domestic violence

restraining order proceedings after the court ensured that all mandated proceedings were covered.

Availability of Court Reporters Has Resulted in Courts Using More Electronic Recording.

The availability of court reporters has resulted in more courts turning to electronic recording to

create records in misdemeanor and limited civil (including eviction cases that fall within the

threshold) proceedings. Electronic recordings may also be used in other civil proceedings, such

as those subject to a Jameson request or at the direction of the court. For example, the Presiding

Judge in the Ventura court issued an administrative order in February 2023 specifying that

(1) court reporters will no longer be provided in family law contempt proceedings given the lack

of available court reporters and (2) electronic recording was authorized to create the record

instead as such proceedings were quasi-criminal in nature.

Limited Data on Extent to Which Availability of Court Reporters Affects Whether Records

Are Created. Due to technological constraints, trial courts generally had some difficulty

providing comprehensive information on the number of proceedings (1) in which records were

created in 2022-23, (2) that were statutorily required to have a record made, (3) in which a record

was made because it was requested by one of the participants, (4) in which electronic recording

is being utilized because court reporters are not available, and (5) in which there is a lack of

record because electronic recording is not permitted by law and a court reporter is not available.

About two-thirds of the trial courts were able to provide some data, but with varying levels of

completeness. Based on this data, the trial courts reported:

• 5.1 million proceedings across all case types in 2022-23 had a record created. Of this

amount, 2.1 million were made via electronic recording—1.9 million in criminal

proceedings, about 350 in juvenile proceedings, and about 185,100 in civil

proceedings. The remaining 3 million records were made by a court reporter—

2.2 million in criminal proceedings, about 390,300 in juvenile proceedings, and about

409,500 in civil proceedings.

• 1.6 million proceedings across all case types in 2022-23 had no record created. This

consisted of about 717,700 criminal proceedings (of which about 60 percent were

infraction proceedings), nearly 22,700 juvenile proceedings (of which about

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 12 March 5, 2024

89 percent were dependency proceedings), and about 864,100 civil proceedings

lacking records. For the civil proceedings lacking records, the most common

proceedings lacking records were unlimited civil proceedings (44 percent), non-child

support family law proceedings (33 percent), and probate proceedings (14 percent).

Availability of Court Reporters Has Created Operational Challenges. As noted above, the

judicial branch estimates that only 62 percent of total court reporter need was met in 2022-23.

However, the estimated need differs significantly by court. Based on data provided by trial

courts, as well as conversations with stakeholders, the diminished availability of court reporter

employees and private court reporters has presented the following key operational challenges:

• Staff Time and Resources Being Used to Manage Court Reporter Coverage. Trial

courts frequently need to spend staff time and resources placing calls to find private

court reporters to cover planned and unplanned absences as well as any increased

demand (such as if more criminal cases than expected are going to trial). They also

must routinely spend staff time assigning court reporters to different courtrooms

multiple times in a day. For example, a court reporter covering a calendar which ends

before noon may then get assigned to another courtroom to provide coverage on

another calendar or a particular case. Similarly, staff must spend time facilitating the

presence of private court reporters hired by attorneys and litigants to cover specific

cases. For example, when multiple private court reporters are present in a single

courtroom for a particular calendar, court staff must dedicate time to scheduling the

proceeding to accommodate them (such as to ensure that they can be physically or

remotely present to make a record of the proceedings).

• Delays and Changes to Court Schedules and Calendars. Courts also can be forced

to adjust schedules and calendars to account for the availability of court reporters.

This can include starting a calendar later as well as delaying or continuing cases.

Courts indicate that Jameson cases are examples of key cases that may get continued

or delayed if court reporters are not available.

• Competition Between Courts for Court Reporters. The decline in court reporter

employees has led to courts competing with one another to hire court reporters. Our

understanding from conversations with stakeholders is that this has prompted

differences in the amount of benefits (such as signing bonuses) offered to incentivize

court reporters to be employed directly by the trial courts (which we discuss in more

detail below) as well as the total compensation packages offered by trial courts.

Additionally, key stakeholders indicated that the rates paid to private court reporters

to provide coverage have also increased over time. Since private court reporters are

able to choose whether they accept a particular assignment or not, differences in the

amounts courts are willing to pay can also result in courts competing with one another

for private court reporter services. In conversations with stakeholders, it appears that

court reporters are generally aware of the compensation offered by courts—as well as

how courts generally use and treat their court reporters.

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 13 March 5, 2024

• Pay for Non-Court Reporting Positions. Based on conversations with stakeholders,

certain court administrators are considering how court reporter compensation

compares to compensation for other positions within the court (such as managers or

information technology administrators). Some concern was expressed that increases

in court reporter compensation caused by competition for court reporters could result

in their pay exceeding those of managers and other professional classifications. This

could put pressure on administrators to increase compensation for those positions—

and thus overall operational costs.

TRIAL COURT SPENDING ON COURT REPORTERS

Amount Spent by Trial Courts to Support Court Reporter Services

More Than $200 Million in Estimated Court Reporter Expenditures Annually. The judicial

branch estimates that more than $200 million is spent annually on court reporters or to create a

record in trial court proceedings. (This does not include the $30 million provided annually

beginning in 2021-22 to increase court reporters in family and civil cases, which are discussed

later in this letter.) As shown in Figure 9, an estimated $237 million was spent on such services.

Of this amount, $214 million was estimated to be spent on court reporter services—$209 million

budgeted for court employees and $5 million actually spent on private contract services. (Due to

information technology system constraints, the judicial branch was not able to provide data on

the specific amount actually spent on court employees.) The remaining $23 million was spent on

transcript costs as well as costs related to electronic recording. Between 2020-21 and 2022-23,

the amount spent on court employees has decreased, while the amount spent on contract services

as well as transcripts and electronic recording has increased.

Fees Authorized Only Offset a Portion of Civil Court Reporter Expenses. State law

authorizes $30 of certain civil filing fees be set aside as an incentive for courts to provide court

reporters in civil proceedings. This funding is only available to trial courts who actually provide

such services. (We note that Judicial Council has the authority to use these revenues to help

support trial court operations.) Additionally, as noted above, state law generally requires a

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 14 March 5, 2024

$30 fee be charged for proceedings lasting an hour or less and that actual costs generally be

charged for proceedings lasting more than an hour in non-mandated civil proceedings. As shown

in Figure 10, nearly $22 million in fee revenue was collected from the authorized fees. Of this

amount, $18 million came from the share of filing fees set aside as an incentive to provide court

reporter services in civil cases. The remaining $4 million came from fees charged for

non-mandated civil proceedings lasting less than one hour ($2 million) and those lasting more

than one hour ($2 million). The judicial branch estimates that $80 million was spent on providing

court reporter services in civil proceedings generally in 2022-23. (We note that, because trial

courts do not track court reporter time by individual case type, the judicial branch estimates that

about 37.5 percent of court reporter time is spent on civil proceedings. This percentage was then

applied to the total amount spent on court reporter services.) Accordingly, if this full $22 million

in fee revenue was used to offset court reporter costs in civil proceedings, it left a net cost of

$59 million to be supported by trial court operational funding.

Impact of Dedicated Funding for Increasing Court Reporters in Family and Civil

Proceedings

State Provided Funding to Increase Court Reporters in Family and Civil Law Proceedings.

Beginning in 2021-22, the state budget has annually included $30 million from the General Fund to

be allocated by Judicial Council to the trial courts to increase the number of court reporters in family

and civil law proceedings. The budget prohibits the funding from supplanting existing monies used

to support court reporter services in such cases and required any unspent monies revert to the General

Fund. Judicial Council allocated the funding to individual trial courts proportionately based on the

level of judicial workload in noncriminal cases, but ensured that the smallest courts received a

minimum of $25,000 in order to be able to support a 0.25 FTE court reporter position.

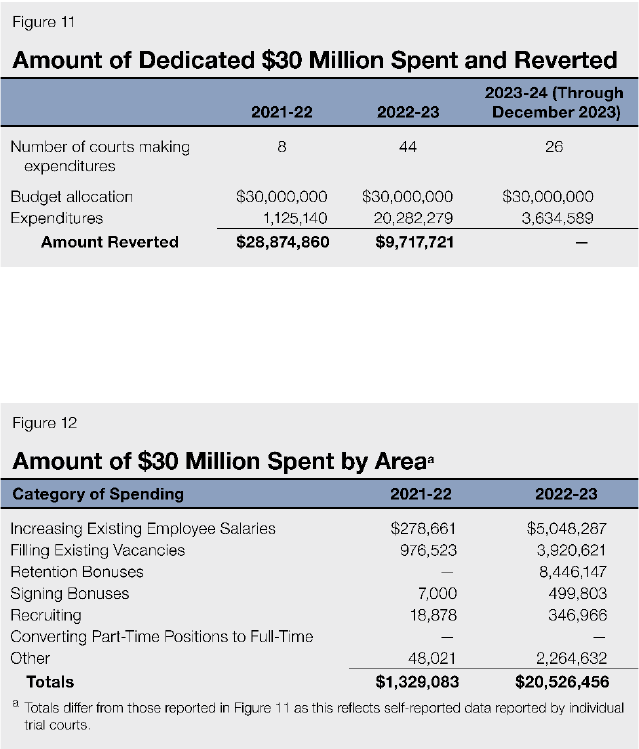

Amount Reverted Initially High, but Now Declining. As shown in Figure 11 on the next

page, only $1.1 million of this allocation (4 percent) was spent in 2021-22—resulting in the

reversion of $28.9 million (96 percent). In conversations with stakeholders, the lack of

expenditures seems attributable to differences in the interpretation of budget bill language

specifying how the monies could be used. The 2022-23 budget package included amended

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 15 March 5, 2024

budget bill language to provide greater clarification on how this dedicated $30 million could be

used. (This language is also included in the 2023-24 budget and in the proposed 2024-25

budget.) Under the amended language, trial courts are specifically authorized to use the money

for recruitment and retention, filling existing vacancies, converting part-time positions to

full-time positions, increasing salary schedules, and providing signing and retention bonuses in

order to compete with the private market. As shown in Figure 11, the amount spent increased

substantially to $20.3 million of the allocation (68 percent) in 2022-23—resulting in the

reversion of $9.7 million (32 percent). Additionally, the number of courts making expenditures

using this money increased from 8 courts in 2021-22 to 44 courts in 2022-23. Through the first

half of 2023-24, 26 courts have already reported using a share of this funding.

Amounts Spent on Similar Categories of Benefits. As shown in Figure 12, trial courts spent

their monies in similar categories. In 2021-22, the most common expenditures were to increase

existing employee salaries and to fill existing vacancies. In 2022-23, retention bonuses were the

most common expenditure area.

Specific Benefits Offered Vary by Court. As shown in Figure 13 on the next page, a number of

courts are offering benefits in areas in which the $30 million in dedicated funding can be spent.

However, based on their needs, the local market for court reporters, and various other local factors

(such as the cost of living), these offerings can look very different. For example, the Los Angeles

court offered an up to $50,000 signing bonus for a new full-time court reporter employee (with a

specified amount payable after every six months) that remained employed for two years in

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 16 March 5, 2024

2023-24. This bonus is limited to the first 20 new FTE hires since it was first offered. In contrast,

the Humboldt court offered a $10,000 signing bonus paid in four equal installments over the first

year of employment. Similarly, courts are offering various benefits based on their needs—which

are captured in the “Other” category. Common expenditures in this area include finders/referral

fees; professional, equipment, and technology stipends; tuition reimbursement for court reporting

school; increased rates or services from private contractors; and other costs.

Amount Reverted by Court Varied in 2022-23. As shown in Figure 14 on the next page, the

amount reverted by each trial court varied in 2022-23. Approximately 64 percent (37 trial courts)

reverted more than 40 percent of their share of the $30 million dedicated allocation. Various

factors could account for why courts may have spent more or less of their allocation. For

example, expenditures could have been delayed due to the need to obtain union approval to offer

a particular benefit (such as to increase existing court employee salaries). In addition, whether

costs are incurred from offering certain benefits (such as a signing bonus or court reporting

school tuition reimbursement) depends on whether court reporters or others respond to the

benefit. For example, a court that offers a signing or referral bonus will not incur expenditures if

no one chooses to apply to become a court reporter at that court.

Allocation Benefited Mostly Existing Employees. In examining data provided by those courts

who were able to report this level of data, it appears that the dedicated $30 million allocation—

when spent—benefited significantly more existing court reporter employees than new hires, as

shown in Figure 15 on the next page. For example, over 90 percent the of the employees

(996 FTEs) benefitted in 2022-23 were existing employees. Some of the benefits offered—such as

increasing salaries for existing employees, retention bonuses, and longevity bonuses—are

specifically targeted to existing court reporter employees. Delaying their departure helps prevent

trial court need for court reporters from growing worse. However, the benefits offered to existing

employees to encourage them to stay also likely benefit some employees who had no intention of

leaving, meaning a portion of such expenditures do not directly increase the availability of court

reporters. Other benefits offered—such as signing bonuses or increasing the starting salary for

court reporters—are more targeted towards new hires. Such new hires can help reduce the number

of court reporter vacancies at a court—directly increasing the availability of court reporters.

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 17 March 5, 2024

Full Impacts of Benefits Offered by Courts Still Unclear. The full impacts of the benefits

supported by the $30 million in dedicated funding are still unclear. This is because the trial

courts only began making use of this funding in a significant way in 2022-23 with 44 courts

making expenditures. In addition, trial courts have been adapting what is being offered based on

the responses they receive. For example, certain courts increased the amount they offered for

certain benefits—such as bonuses and stipends—in order to attract more applicants and potential

hires. As such, the impacts of these modified benefits may not yet be fully realized. Additionally,

in conversations with stakeholders, the trial courts have also offered or are considering offering

new types of benefits to potentially attract more court reporters. For example, we have heard that

some courts are authorizing part-time court reporter positions and may be considering

partnerships to help court reporter students (in particular voice writers) successfully complete

their programs and pass the licensing examination. Some of these changes—such as authorizing

part-time court reporter positions—may have limited fiscal costs but could have meaningful

impact on court reporters. However, the full impacts of the benefits—some of which may be

novel or creative—may not be observed until they are fully implemented and tested.

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 18 March 5, 2024

TRIAL COURTS COMPETING WITH PRIVATE SECTOR FOR COURT

REPORTERS

Active In-State Licensees Exceed Trial Court Need

In 2022-23, California had 4,752 active, in-state, licensed court reporters. From a May 2023

DCA occupational analysis of court reporters, 41 percent of surveyed court reporters reported

that their primary work environment was the court—roughly 1,948 individuals. In the same year,

the judicial branch estimated 1,866 FTE court reporters would be needed to provide court

reporters in all proceedings except infraction, misdemeanor, and limited civil proceedings and

that 1,164 FTEs were currently providing service. While multiple individuals can comprise a

single FTE, this gap suggests that there are a number of court reporters who predominantly

provide service to the courts but are choosing not to be directly employed by the trial courts. This

would include private court reporters who the courts contract with to provide services when court

reporter employees are unavailable. Additionally, there are a number of licensees who are

choosing to be employed by the private market and not work for the court system. In

combination, this suggests trial courts could be having difficulty competing with the private

market to procure court reporter services—thereby causing some of the operational difficulties

including competition between trial courts, described above.

Three Key Factors Impacting Trial Court Ability to Compete With Private Sector

In conversations with various stakeholders, we identified three key factors that seem to be

impacting trial courts’ ability to compete with the private sector to attract court reporter

employees. This then also creates competition between courts. We discuss each factor in more

detail below.

Perception of Higher Compensation in Private Sector. There is a perception that

compensation in the private sector is greater than in the trial courts as private court reporters—

particularly those who are hired by attorneys—are able to charge desired rates by case or

proceedings. We have heard, for example, that this can result in a couple of thousand dollars

being charged per day or even half-day. However, we note that it is difficult to fully compare

compensation for trial courts’ court reporter employees with those in the private market. Court

reporter employees generally receive, in addition to their salary, health and other benefits, as

well as retirement or pension benefits which are guaranteed for being available during a set

period of time regardless of whether their services are needed. In contrast, while private court

reporters are free to charge the rate they desire, they generally do not receive the same level of

health, retirement, and other benefits as court reporter employees. Additionally, they are not paid

if they do not work, sometimes including in cases where they have reserved time for a trial that

does not occur (such as due to the case being settled at the last minute). (We note, however, that

some private court reporters have negotiated cancellation charges to help partially offset such

losses in compensation.) This means the rates that private court reporters charge must cover their

benefits as well as time that is spent not being employed. As such, private court reporters have

less stable income and work hours. Thus, while private court reporters may earn more per day

they are working, some may ultimately be compensated less over the course of a year.

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 19 March 5, 2024

Accordingly, it difficult to assess whether the full compensation provided to court reporter

employees is higher or lower than that earned by private court reporters.

Perception of Better Working Conditions in Private Sector. From conversations with

stakeholders, working conditions are another key factor impacting whether court reporters

choose to be court reporter employees at the trial courts or private court reporters. Court

reporters hired by the court generally work for the entire business day physically in courtrooms.

A number are no longer assigned to the same courtroom and/or judge and, as a result, are

constantly moving between courtrooms—or even entire facilities (such as driving from one

courthouse to another in a day)—as directed by court administration. They also generally do not

have a choice in what proceedings they are assigned to create a record for. Busy calendars can

also lead to court reporter employees having to keep up with the quick pace and length of the

calendar. For example, stakeholders have expressed that court reporter employees new to the

industry sometimes struggle to keep up. Some court reporter employees are also effectively

required to prepare transcripts outside of their normal working hours because they are in court

for most of the day. As noted above, court reporters separately charge for the preparation of

transcripts meaning that some court administrators view this as work that should not be done

during the business day, which is compensated via the court reporter’s salary. In combination,

stakeholders have indicated that this can make the work environment very stressful as well as

physically and mentally draining. In contrast, private court reporters have much more flexibility

in their working conditions. Most notably, private court reporters are able to pick and choose

which courts they work in and what cases or proceedings they are willing to cover. This provides

significant flexibility to determine how many hours they work, including the amount of time

spent in the courtroom. Additionally, private court reporters are able to provide services

remotely—which allows them to work at more courts and provides them with flexibility to

maximize their working time that otherwise would be spent on travel. If they must be present in

person, they are able to negotiate travel expenses as well. In combination, stakeholders indicate

that this flexibility allows private court reporters to create the work environment they desire.

Moreover, higher levels of autonomy can generally boost overall morale. As such, stakeholders

indicated that this flexibility was of great enough importance that the trade-off of less guaranteed

income and potentially less net total compensation in working was deemed worthwhile.

Trial Court Recruitment and Retention Activities Could Be Insufficient. It is unclear

whether current trial court activities are sufficient to recruit (and retain) new court reporters in

the trial courts. The trial courts need to be proactive at ensuring there is steady supply of court

reporters willing to work for them as they are a major employer of court reporters and require

them to provide litigants with due process in court proceedings. However, it appears that many

licensed court reporters are currently unwilling to work for the trial courts. This is evidenced by

the fact that the number of active in-state court reporter licenses exceeds trial court need yet the

trial courts continue to indicate they have an unmet need. While the trial courts have recently

become more actively engaged by offering the benefits discussed above, data suggest this seems

to have had limited impact on bringing new hires to the courts in the short run. For example, the

reported number of court reporter employees departing has continued to outpace the number

being hired. As such, the trial courts may need to consider expanded or improved recruiting

activities. For example, some sort of collaboration with schools or new hires to guarantee

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 20 March 5, 2024

employment or provide real-life practical experience could be utilized to recruit people to go to

court reporting school as well as to increase the likelihood new court reporters succeed in the

trial courts and choose to remain employed there. Similarly, targeted recruiting activities—such

as by conducting a survey of what benefits or working conditions would be attractive enough for

private court reporters to choose to become and remain public employees—would provide

helpful insight to inform how trial court compensation or working conditions may need to be

adjusted to recruit more individuals. Absent these increased targeted recruitment efforts, it will

likely be difficult for trial courts to meaningfully compete with the private market for court

reporter services and ensure their needs are met on an ongoing basis

KEY QUESTIONS FOR LEGISLATIVE CONSIDERATION

The data and information provided in conversation with stakeholders suggest that the trial

courts are having difficulty obtaining and maintaining a sufficient number of court reporters.

More importantly, this means that courts are also having difficulty providing a record in all of

the proceedings that could benefit from it. Below, we provide eight key questions that would be

important for the Legislature to answer when determining what action(s) should be taken should

the Legislature decide to address these issues.

Is the Availability of Court Reporters in Trial Courts a Limited-Term or Long-Term

Problem? The Legislature will need to decide whether the difficulty the trial courts are having to

hire and retain sufficient court reporters is a limited-term or long-term problem. Given that voice

writing has just been authorized, its full impact on the overall court reporter licensee population

has yet to be realized. However, there are promising signs that voice writing may both increase

overall court reporter licensees as well as court reporter availability in the trial courts. If the

Legislature believes that there will be more court reporters in the near future, it can focus its

actions on more immediate term fixes to address trial court difficulty in the short run. For

example, the Legislature could temporarily authorize the use of electronic recording in more case

types for a couple of years or temporarily allow for court reporters to appear remotely to increase

their availability (as they would not need to travel between court locations). However, if the

Legislature determines this is a longer-term issue (such as if it believes there will always be a

robust and competitive private market), more structural changes in how trial courts employ

and/or use court reporters may be necessary.

What Methods of Making a Record Should Be Permissible? The Legislature will need to

decide what methods of making an official record should be permissible. This includes whether a

record can be made by electronic recording, a court reporter provided by the court, or a private

court reporter employed by an attorney or litigant. Under current law, electronic recording is

limited to certain proceedings—though some courts have expanded its use in critical proceedings

to ensure due process given the lack of available court reporter resources. Allowing for its

expansion could help reduce the need to for court reporter services by the trial courts and

increase the number of records that are made in the short run (such as if the expansion was

granted for a short, defined period) or in the long run (such as if the expansion was indefinite).

Expansion of electronic recording could also help improve due process and equity. This is

because in the absence of a court reporter, a record will not be made unless an attorney or litigant

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 21 March 5, 2024

pays for their own court reporter. This means individuals who cannot afford a court reporter

could end up lacking a record of their case, making it harder for them to appeal or to substantiate

a claim before the Commission on Judicial Performance related to judicial misconduct. It could

also reduce overall trial court operational costs as electronic recording generally has lower

ongoing costs to operate and generate records. This is a notable benefit given the state’s budget

problem.

Should Court Reporters Be Allowed to Appear Remotely? State law has authorized the

ability for judicial proceedings to be conducted remotely—including ones which involve court

reporters. However, under existing law, court reporters provided by the courts are generally

required to be present in the courtroom. In contrast, private court reporters contracted by the

court, attorneys, or litigants may appear remotely. The Legislature may want to consider the

trade-offs of having a court reporter being physically present in a courtroom versus being present

remotely while creating the record. These trade-offs may differ by case type or proceeding. If

there is not a substantial difference, allowing trial courts to use their court reporter employees

remotely could free up more of their court reporters’ time (such as by minimizing the need to

travel), improve overall court operational efficiency, and improve working conditions for some

court reporters. This could help improve recruitment and retention.

Should Court Reporter Resources Be Pooled Between Courts? Currently, individual courts

hire court reporter employees and private court reporters to cover cases in their respective

county. The ease of finding such coverage varies by court based on their geographic location and

other factors. As such, the Legislature could review whether the pooling of court reporters

between courts, such as regionally or statewide—would be appropriate. For example, the

Legislature could determine that it would be appropriate to maintain a regional or statewide pool

of court reporters to temporarily fill in for court reporter vacancies or absences (in a manner

similar to the assigned judges program). This could help reduce or even eliminate the need for

individual trial courts to constantly seek private court reporters to fill any coverage gaps. The

Legislature could also consider even going further by pooling all court reporters statewide and

allowing them to cover cases remotely on a regular basis rather than just to cover temporary

vacancies. We note that doing so would minimize the competition between courts for court

reporters. It could also provide greater flexibility to incorporate court reporter desires related to

the number of hours worked and/or the types of proceedings they individually cover. However,

this would likely require significant negotiations with unions as contracts with court reporters are

currently established on a court-by-court basis.

Should the Courts Work With Court Reporting Schools or Others to Improve Recruitment

and Retention? Because the courts are a major employer of court reporters in the state, the

Legislature could consider whether there is a need for the courts to work more closely with court

reporting schools, court reporters, or others (such as high schools) to recruit, train, and prepare

people to work successfully in a trial court setting. This could include a stipend and/or tuition

reimbursement offered while individuals are in school or training or after they have worked in

the court for a certain number of years (similar to a loan repayment program). It could also

include allowing court reporting students to intern in the courts, such as by practicing making

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 22 March 5, 2024

records and getting feedback from existing court reporters. Given the state’s budget condition,

however, new state funding to support such options is unlikely to be available in the near term.

How Many Court Reporters Do Trial Courts Need? As noted above, the judicial branch

provided its estimated need for court reporter services assuming 1.25 FTE court reporters are

needed per judicial officer, excluding the case types for which electronic recording is authorized.

However, decisions made by the Legislature could change how many court reporters are needed.

For example, the Legislature could (1) choose to expand electronic recording to certain case

types (decreasing the need for court reporters), (2) match the number of court reporters to

number of courtrooms in which court reporters are now necessary (which would be less than the

1.25 FTE per judicial officer), and (3) utilize a statewide pool of court reporters to cover for any

temporary vacancies or absences. This would have the effect of reducing the number of court

reporters needed by the trial courts. Depending on the specific choices made by the Legislature,

more or less court reporter FTEs could be needed by the trial courts.

How Should Court Reporters Be Funded? The Legislature will want to consider how it

wants to fund court reporters moving forward. Currently, support for court reporters is generally

included as part of the funding for overall trial court operations. This means that funding can be

used for other costs based on the priorities and needs of individual trial courts. If the Legislature

determines that court reporter funding is of a high enough priority to segregate it to ensure it can

only be used for that purpose, the Legislature could consider making it a specific line item in the

budget. This would be similar to funding provided for court-ordered dependency counsel and

court interpreters. We note that taking this step would be necessary if the Legislature chose to

pool court reporter resources statewide. The Legislature could also consider the extent to which

fees are used to support court reporter services. If higher fees are charged and more revenue is

collected, it could help offset any increased costs from other changes intended to increase the

availability of court reporters (like new recruitment programs). Alternatively, it could help

reduce the General Fund cost of court reporting services, a notable benefit given the state’s

budget problem. The Legislature could also consider other changes, such as reducing or

standardizing the fees charged, which could make access to court records more equitable. This

could be difficult if the loss in fee revenue was backfilled with General Fund support given the

state’s budget condition, however. Finally, the Legislature may want to consider whether it

makes sense to expand the use of the $30 million originally provided to increase court reporters

in family and civil proceedings to all proceedings. This is because trial courts will need to

prioritize coverage in mandated proceedings first.

How Can Government Compete With the Private Market? The Legislature will want to

consider the extent to which it is willing to compete with the private market and what actions it

would like to take to do so. It may be difficult for the state to compete with the hourly or daily

pay rate offered in the private market. As such, the Legislature could instead consider whether

there are changes that could be made to working conditions to make court employment more

attractive. For example, this could include allowing remote appearance, offering part-time

employment, or allowing court reporters to work on transcripts during the business day. To

address competition between courts, as well as the private market, the Legislature could also

consider whether to standardize compensation either statewide or in regions of the state. For

Hon. Thomas J. Umberg 23 March 5, 2024

example, judges across the state generally receive the same compensation. The Legislature could

also consider the extent to which private court reporters hired by attorneys or litigants are

permitted to make records in courts. Restricting access to the courts could encourage more

private court reporters—particularly those that are already primarily working with the courts as

private contractors—to become court reporter employees. However, it would require that the

state take steps to ensure it attracts sufficient employees to no longer need to rely on private

court reporters. This could include taking some of the steps we describe above, such as allowing

remote appearance, increased work flexibility, or other options to improve working conditions.

While it could also include increasing compensation, this could be difficult given the state’s

budget condition. Alternatively, the state could reduce its need for court reporters by authorizing

more proceedings to be covered with electronic reporting. If the Legislature is not willing to take

such steps, restricting private court reporter access to the trial court could worsen the problem if

more court reporters depart and there is no access to court reporters.

We hope you find this information helpful. If you have any questions or would like to further

discuss this issue, please contact Anita Lee of my staff at [email protected] or

(916) 319-8321.

Sincerely,

Gabriel Petek

Legislative Analyst