DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 359 404

CE 064 065

AUTHOR

Lightner, John W.

TITLE

A Survey of the Professional Audio Industry in an

Eight State Region To Assess Employers' Perceived

Value of Formal Audio Education and Their Perceived

Training Needs for Entry-Level Employees.

PUB DATE

93

NOTE

173p.; M.S. Thesis, Ferris State University.

PUB TYPE

Dissertations/Theses

Masters Theses (042)

EDRS PRICE

MF01/PC07 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS

*Audio Equipment; Community Colleges; *Education Work

Relationship; *Employer Attitudes; Employment

Potential; *Employment Practices; *Employment

Qualifications; *Entry Workers; Higher Education; Job

Skills; Labor Needs; Two Year Colleges

IDENTIFIERS

Lansing Community College MI

ABSTRACT

A community college conducted a study to determine

how employers perceived formal education for audio

professionals--both baccalaureate and associate degrees from

community colleges, employers' training needs, how they judged

entry-level employees' qualifications, and the availability of

internships and entry-level employment. The study surveyed 564 audio

professionals in an 8-state region, with 154 (27 percent)

responses.

The survey found that most employers (recording studios)

were very

small (three or fewer full-time employees with about the

same number

of part-time and contract employees). A predominant finding is that

industry practitioners want the schools to form attitudes

as well as

technical skills. Respondents cited the need for "people skills"

above technical skills; thinking skills were also requested. Most

wanted applicants to have a bachelor's degree

or at least 2 years

experience past a two-year degree. Employers also tended to emphasize

the traditional studio gear, indicating that these smaller studios

have not been able to upgrade to the technological advances in

the

industry. The outlook for entry-level jobs

was not good, and

employers also did not like to use interns. Four conclusions

were

reached: the community college needs to do public relations work

within the audio community to raise the perception of the abilities

of students with two-year degrees; attitudes should be taught in

a

formal setting; internship opportunities should be pursued by

the

college; and follow-up research of the college's graduates should

be

undertaken. (Nineteen appendixes contain the questionnaire,

cover

letter, explanations for the study, and detailed analysis of

responses to questions. A bibliography lists 29 references; 29 tables

are included in the report.)

(KC)

***********************************************************************

*

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that

can be made

*

*

from the original document.

*

***********************************************************************

A SURVEY OF THE PROFESSIONAL

AUDIO INDUSTRY IN AN EIGHT STATE

REGION TO ASSESS EMPLOYERS PERCEIVED VALUE

OF FORMAL AUDIO EDUCATION AND THEIR

PERCEIVED TRAINING NEEDS FOR ENTRY-LEVEL EMPLOYEES

by

John W. Lightner

U S OEPARTMENT OF

EDUCATION

Off

of ECII.K.st.Ohe, Research

and ,hp,o,e-^en!

ED CA TIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION

CENTER ERIO

me document has

been reproduced as

reee.ved from the person

or ohgan,zaheh

oraonetonO

Uhler changes nave

been made to improve

reOrOduChOn Ouahty

Pcnts of mew or

oprugnS Staled

,h tros

dOCu

ment do not neCeSeerily

represent offiChil

OERI ggs.hgn Or policy

PERMISSION TO

REPRODUCE THIS

MATERIAL HAS BEEN

GRANTED BY

/7 74.-14,t7

TO THE EDUCATIONAL

RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER

(ERIC1."

A Thesis

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science in Occupational Education

in the College of Education

Ferris State University

Winter 1993

2

BEST COPY AMAMI

Copyright © 1993

John W. Lightner

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author wishes to express his appreciation to those

individuals who were instrumental in the completion of this work.

Dr. Ed Cory, who was the project advisor, for his willingness to

help in working through the many schedule conflicts that arose

from my full-time employment at Lansing Community College while

trying to write a thesis and for his guidance in the project.

Dr. James Greene, my Program Director at L.C.C., for his support,

counsel, and critical reading of the final manuscript.

Mr. Marc

Smyth for his input on data processing concerns.

Mrs. Bonnie

McGraw and Mr. John Witt for their assistance in preparing the

mailing pieces.

Certainly no acknowledgement would be complete-

or appropriate--without thanking my family for their support,

especially at certain critical times when becoming a recluse was

necessary to complete the task at hand.

I would also like to

thank all those busy individuals in the professional audio

industry who took the time to thoughtfully respond to my

questionnaire.

It is my hope that the input they have given will

be helpful in making audio education better able to do more to

meet their needs.

Page

4

Table of Contents

Page

Chapter I: THE PROBLEM

Introduction and Background

1

Statement of the Problem

3

Statement of Research Questions

4

Scope of the Study

4

Assumptions

4

Outline of the Report

5

Chapter II: REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

Organization

6

Historical Background

6

Literature Related to the Research Problem

The Changing Nature of Apprenticeship

7

A Potpourri of Industry Input and Criticism

9

How Should the Schools Respond?

13

Literature Related to Mail Survey Questionnaires

General

16

Design Considerations

17

Summary of Literature Reviewed

24

Chapter III: PROCEDURES

Description of Research Methodology

27

Research Design

27

Selection of Subjects

27

Instrumentation

Data Collection

28

Development of the Questionnaire

28

Revision of the Questionnaire

28

Administration of the Questionnaire

29

Data Processing and Analysis

30

Chapter IV: RESEARCH FINDINGS

Introduction

31

Demographics

31

Research Question 1

38

Research Question 2

43

Research Question 3

46

Research Question 4

48

Miscellaneous

50

Mailing Data

. .

.

51

Qualitative Findings

General

55

Response Sorts

58

Explanation of Findings

62

Page ii

5

Table of Contents (cont.)

Page

Chapter V: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Introduction

64

Review of Procedure

65

Recommendations

66

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Questionnaire

A-1

Appendix B: Cover Letter

B-1

Appendix C: Question #1: Listing of "Other"

Business Activities

C-1

Appendix D: Question #11: Listing of "Other"

Disciplines

D-1

Appendix E: Question #12: Listing of Explanations

E-1

Appendix F: Question #13: Listing of Other

Qualifications

F-1

Appendix G: Question #15: Other Training Needs

G-1

Appendix H: Question #16: Listing of Specific Gear

. .

H-1

Appendix I: Question #17: Evaluations of Two- and

Four-Year Graduate's Interpersonal Skills

I-1

Appendix J: Question #18: Evaluations of Two- and

Four-Year Graduate's Communications Skills

J-1

Appendix K: Question #19: Respondent's General Comments

on Student Preparation by Post-Secondary Schools

.

. K-1

Appendix L: Question #23: Respondent's Suggested

Questions

L-1

Appendix M: Comments to Question #12 by Respondents

Preferring Associate's Degree

M-1

Appendix N: Comments to Question #12 by Respondents

Preferring Bachelor's Degree

N-1

Appendix 0: Comments to Question #12 by Respondents

Answering Question #10 Other than Associate's

or

Bachelor's

0-1

Appendix P: Other Areas for Question #13 by

Respondents Whose Primary Business Activity

is "Recording Studio" or "Audio Post Production"

.

P-1

Appendix Q: Pre-Employment Training (question #15)

Preferences by Respondents Whose Primary Business

Activity is "Recording Studio" or "Audio Post

Production"

Q-1

Appendix R: Other Areas for Question #13 by Respondents

Whose Primary Business Activity is "Sound

Reinforcement-Local," "Sound Reinforcement-Regional,"

or "Sound Reinforcement-National"

R-1

Page iii

6

Table of Contents (cont.)

Page

Appendix S: Pre-Employment Training (question #15)

by Respondents Whose Primary Business Activity

is "Sound Reinforcement-Local," "Sound

Reinforcement-Regional," or "Sound

Reinforcement-National"

S-1

ENDNOTES

END-1

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIB-1

List of Tables

Table

Page

1

Primary Business Activities of Respondents

32

2

Recording Studio: Number of Business Activities

33

3

Audio Post Production: Number of Business Activities

34

4

Sound Reinforcement-Local:

Number of Business Activities

35

5

Full-Time Employees

6

Part-Time Employees

36

7

Sub-Contractors

37

8

Educational Level Preference

38

9

Desired Educational Level

39

10

Rank-Ordered Disciplines for Associate's

or Bachelor's Degree

40

11

Four-Year vs. Two-Year Rating

41

12

Interpersonal Skills

41

13

Communication Skills

42

14

Training Areas

43

15

Additional Training Areas

45

16

Train On Specific Brands

45

17

Experience Factor In Hiring

46

18

Rank-Ordered Job Qualifications

47

19

Number of Interns Each Year

48

20

Interns Compensated

49

21

New Entry-Level Each Year

49

22

Like Results

50

23

Additional Questions

51

Page v

8

List of Tables (cont.)

Table

Page

24

Mailing Summary

52

25

Mailing Corrections

52

26

Unforwardable By State

53

27

Forwarded To New Address By State

54

28

Addressed O.K.

54

29

Respondents By State

55

Page vi

CHAPTER I

The Problem

Introduction and Background

This study was undertaken to determine how employers

perceived formal audio education, their training needs, how they

judged entry-level employees' qualifications, and the

availability of internships and entry level employment.

This was

done in an effort to determine how the changing nature of the

industry may be best served by formal post-secondary education

and training.

The fields of Audio Recording, Audio Production, and Sound

Reinforcement have traditionally defined the professional audio

vocations in the United States.

Audio Recording deals with

studios whose primary function is in the

area of music recording

for records, tapes, and compact discs.

Audio Production

facilities handle the more commercial end of the business: hard-

and soft-sell productions for commercial and industrial clients.

The venues frequented by popular entertainers

are serviced by

companies in the Sound Reinforcement business who provide sound

support for live audiences at festivals, auditoriums, and

arenas.

These vocations are inextricably tied to the entertainment and

consumer industries which, according to Polon (personal

communication, October, 1991), have been built by the baby

boomers.

But there are economic and technological

pressures placed on

the professional audio industry--like

so many other industries in

Page 1

o

this modern world--which force constant change, much like the

earth in an earthquake zone as it seeks to find a resting place.

"To remain profitable today, a major studio almost has to be in

the production business, as well as the studio business" (Burger,

1988, December, p. 44) and, "Diversification into video- and

film-related markets [allows] studios to tap into new profit

centers" (Chan, 1988, December, p. 20).

Still, one of the more

prominent pressures is the expansion of technology.

Chan (pp. 20

& 22) further relates that the digital audio workstation--an

integration of a variety of hardware into

a single computer

driven system--has become an industry buzzword.

Dunn (1988,

July, p. 61), quoting Ken Pohlman, Program Director of the School

of Musical Engineering at the University of Miami (Florida),

says

that the future lies in the workstation concept.

The

workstation, and other concepts like it will undoubtedly continue

to pressure the industry to change the

way that it functions.

The educational community has responded to the changing

nature of the industry and the increased sophistication of the

technology employed by offering formal educational and training

programs for persons interested in the professional audio

industry.

Polon (1992a, August) capsulizes the genesis of audio

education in this way:

There were a few sparse curriculums in engineering

or physics

with a specialization in audio at

some four-year state schools

Page 2

lI

and one or two good two-year programs by the 1970s, but the

explosion of audio education was a phenomenon of the 1980s.

(p. 92)

With all of this has come a change in the perception of the audio

industry.

Kenny (1990, July) states that, "There comes a time in

most industries when jobs are no longer thought of as trades but

as professions.

We have reached that time in the audio recording

industry."

(p. 35)

Statement of the Problem

This present study was undertaken in an effort to bring

some

objectivity to this rapidly developing field of professional

audio and to provide guidance for the Media Technology Program

at

Lansing Community College as courses are designed and students

counseled.

Quite specifically, this study surveyed audio

professionals in an eight state region to ascertain their

perceived value of the present level of audio education and

to

determine their perceived training needs for potential

entry-

level employees.

Further, this study was undertaken to make a

small beginning at filling the void that exists for

scientifically based studies' in the literature of this

professional vocational area.

Page 3

12

Statement of Research Questions

This study was undertaken to collect data relevant to the

following four research questions:

1.

What value do employers place on formal education?

2.

What are the rank-ordered training needs of employers?

3.

What are the rank-ordered qualifications of entry-level

employees as seen by employers?

4.

What is available to graduates in terms of internships and

entry-level employment?

Scope of the Study

This study was conducted with several limitations.

First, the

professional audio industry is relatively small; having,

according to Polon (personal communication, October 1991), only

about 10,000 jobs in the 'traditional' audio disciplines

previously described.

Second, the population is not well

identified in any type of comprehensive census, although a number

of practitioners can be found in documents of a directory nature

aimed for fellow professionals.

Third, and last, the budget for

this project was of necessity limited and that precluded any

follow-up on non-respondents.

Assumptions

One essential assumption was made as this research was being

designed.

That assumption is that graduates of Lansing Community

College are more likely than not to seek jobs in the region

including Michigan and the surrounding states.

It was for this

Page 4

13

reason that the eight state region of Michigan, Wisconsin,

Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee was

chosen as the geographic limit to this work.

Further, some LCC

graduates seeking a four-year degree have to choosen Columbia

College in Chicago or Middle Tennessee State University at

Murfreesboro, suggesting that they may still remain in the region

chosen.

Outline of the Report

The remainder of this report begins with a review of related

literature in Chapter II.

Here, the existing literature as found

in the professiona. 'trades' and elsewhere is discussed in an

effort to determine the general consensus on the status of audio

education and employment for graduates of such programs.

Also,

the literature pertaining to mail-survey questionnaires is

perused as it relates to a study of this kind.

Chapter III will

detail the procedures used in designing this study, its

instrumentation, as well as data collection and analysis.

In

Chapter IV the research findings will be displayed and discussed

as well as the relationships these findings have to the

literature.

Finally, Chapter V will present conclusions to be

drawn from the results of this study and recommendations for

future research and related activities.

Page 5

14

CHAPTER II

Review of Related Literature

Organization

This present chapter is divided into two parts.

The first is

a review of the existing literature concerning audio education

and its relationship to the industry.

This literature, of

necessity, comes from the 'trade' publications as well as papers

presented at SPARS (Society of Professional Audio Recording

Services) conferences.

This limitation occurs since scholarly

journals containing scientific studies of the industry and/or

audio education could not be located and--given the infantile

nature of audio education--are assumed to be non-existent (See

Endnote 1).

The second part concerns itself with literature

germane to the elements of mail-survey questionnaires such as the

one used to gather the data for the research discussed herein.

Historical Background

Audio as an industry had its beginnings in the traditional

recording studio--a place where music recording for records was

part and parcel of the business.

Only recently has that status

been subject to change.

Martin Polon of Polon Research

International (personal communication, October, 1991) states that

ten years ago a recording studio staff spent about 80% of its

time making recordings for records, but by 1991 only 20% of a the

staff's time was spent in record work.

Today, the engineer who

specializes in music recording is on the wane.

Hirsch (1985,

Page 6

15

Spring, n. pag.) contends that the day of the audio specialist is

gone and that modern audio demands diversification of skills if

an individual is to survive in the present audio environment.

Literature Related to the Research Problem

The Changing Nature of Apprenticeship

The professional audio industry has traditionally taught its

practitioners by using an apprenticeship system where an

individual was employed based on personal characteristics and

trained in-house in the ways of audio craft.

According to Pritts

(1985, Spring), however, "It appears that the system can no

longer trust the ancient apprenticeship method of preparing

employees."

(n. pag.)

He further contends that the ancient

system taught "how to do," not "how to learn."

The

apprenticeship system is not extinct, but its use has become

limited.

Douds (1985, Spring) gives yet another reason for its

dwindling use in that, "This process of apprenticeship is still

used today; however, the costs incurred in training an entry-

level employee form the 'ground up' may be very great!"

(n. pag.)

In addition to the content concerns raised by Pritts and the

cost concerns stated by Douds, Grundy (1984, Fall) points to time

saying that, "Up until the 1960's, in the days when studios were

booked by the week or even by the month, there was ample time for

a seasoned engineer to put his arm around a junior member of the

staff and show him the ropes."

(n. pag.)

Page 7

16

The apprenticeship has undergone a transformation from its

traditional role into a tool used by audio educators to give

students a transition from school to the oft cited 'real world.'

The schools call this phenomenon an internship.

According to

Miriam Friedman, program director at The Institute of Audio

Research, "The big thing a student has to understand is that a

recording studio is a commercial operation.

The internship is

sort of a halfway house where they learn the realities of the

business world." (qtd. in Kenny, 1990, July, p. 41)

This

experience is considered so valuable by the schools that,

according to Kenny (1990, July, p. 38), one is either provided by

the schools or students are required to seek their

own internship

experience as a part of job-search training.

He further states:

The days of hanging out in a studio alleyway, hoping to be

asked inside for the big break, are on the decline.

It's not

that you can't find a job by bumping into the studio manager

at the right time.

It's just that studios, like every other

business in the audio industry, are turning

away from their

own apprenticeship programs for second engineers and are

looking to recording schools for potential employees.

(pp. 32

& 34)

The apprenticeship system is, therefore, prohibitive in relation

to the type of skills taught, its cost, and time constraints

involved.

But transformed into an internship, it plays the role

of transition from school to the everyday world of audio.

Page 8

17

A Potpourri of Industry Input and Criticism

Prior to the time when a student is ready for an internship

the schools have a variety of facts, concepts, principles,

skills, and attitudes to address.

According to Pritts (1985,

Spring) the students want the schools to help them to prepare for

a technical world that doesn't yet exist, but he quickly counters

that, "The biggest favor we can do them is to make them

'educatable.'"

(n. pag.)

David Leonard, chief administrator of

Trebas Institute of Recording Arts, flatly states that, "The most

important thing we're trying to do is to help students learn how

to think, how to solve problems, how to work in different

situations in studios." (qtd. in Dunn, 1988, July, p. 64)

And

Hirsch (1985, Springl adds the conclusion: "And finally we must

teach professional attitudes and increase awareness of what goes

on day-to-day in the world of audio."

(n. pag.)

But why not just teach students how to operate equipment?

Friedman asserts that, "The operator who understands technology

is, in fact, a much more sophisticated operator." (qtd. in Kenny,

1989, July, p. 73)

In fact, the advent of the microprocessor

(Alan Kefauver, director of recording arts and sciences at

Peabody Conservatory, qtd. in Kenny, 1990,

p. 36) has made

education a much more important part of preparation for the world

of work in audio.

Moylan (1988, December) says, "Today, a market

exists for computer-literate individuals (in fact, long-term

employment without some computer knowledge is not likely)."

(p.

30)

And to those who would insist that creativity is all that is

Page 9

18

required, Lambert (1989, July) adds, "Even if we are born with

that creative spark, we must learn the necessary skills to take

advantage of opportunities presented to us." (p. 14)

Perhaps the greatest amount of criticism comes as a result of

graduates' poor command of 'people skills,'

Lambert (1989, July)

chides,

"I seldom hear of students being involved in classes that

feature 'Psychology of the Talented Artist' or 'How to Salvage a

Perilously Rebellious Overdub Session.'" (p. 23)

A further

criticism comes from John Fry, owner of Ardent Recordings

(Memphis, TN), who says,

". . .

often we really don't teach too

much about what it's like to work, and what the elements of

delivering service and excellence in work are." (qtd. in

Jacobson, 1988, July, p. 107)

The need for thinking skills and appropriate attitudes is

driven as much by technology as it is by the people-centered

nature of the audio business.

What happens to the engineer who

has worked twenty years in the business and is overtaken by

technology?

Without the ability and initiative to engage in

self-training, he/she will render himself/herself unemployable.

Pritts (1985, n. pag.) warns that the need for retraining is

totally dependent upon the ever changing technology that the

industry uses.

Potyen (1988, July) graphically states it thus,

"It seems no matter how many machines you learn to use, the army

of the latest generation machines continues to advance--sort of

like Mickey Mouse and the insurgent brooms in the 'The Sorcerer's

Apprentice' from the Disney classic, Fantasia."

(p.

61)

Page 10

A quick glance at the section titled "Recording Schools,

Seminars & Programs" in the Mix Master Directory of the

Professional Audio Industry immediately reveals a variety of

entries ranging from four-year schools to seminars lasting just

weeks.

Which of these will prepare a student for long-term

employment in the audio industry?

According to Pritts (1985,

Spring), "Short courses in a craft are best applied in gaining

'craftsmanship,' but are of little use to someone who cannot

apply it to a firmer knowledge base." (n. pag.)

He goes

state that multi-year studies that offer no hands-on are

better since,

"

. .

they never get around to showing us

on to

little

'why' or

to fostering creativity."

(n. pag.)

Lambert (1989, July)

elaborates on this theme: "So those training sessions in the

school or university--usually involving too few actual hands-on

hours at the board, and seldom if ever with 'uncooperative' or

'anxious' clients--offer little comparison to real life." (p. 23)

It could be inferred that Alexander (1985, Spring) is offering

an opposing view when he states, "The goals of many audio

educational programs are centered around student wants and do not

always reflect the actual skills required in the workplace." (n.

pag.)

Opposing in that students always want more hands-on and

minimal theory.

Dee Robb, owner of Cherokee Recording Studios

(Los Angeles, CA), offers a similar complaint by saying,

". . . I

think the schools are very subjective in the

way they teach

people; out of touch with what's going on." (qtd. in Jacobson,

1988, July, p. 173)

Page 11

2.0

For the schools which do provide hands-on training with

industry representative audio equipment, some important--and

expensive--choices must be made.

Igl (1988, July) contends, "It

is recommended practice in vocational technical education to

replicate tools, materials and working conditions of industry as

closely as possible in the training environment." (p. 64) How

close must this be?

Recording engineer Mike Mancini states, "Now

the industry as a whole dictates what you have to buy. You've

got to have a SSL or a V-Series Neve and Mitsubishi or Sony

digital tape machines." (qtd. in Burger, 1988, December, p. 46)

Jimmy Dolan of Streeterville Recording Studios (Chicago, IL)

agrees, "There's got to be hands-on experience with this

equipment (SSL and Neve consoles] and that's not been part of an

apprenticeship or internship program." (qtd. in Jacobson, 1988,

July, p. 172)

At the same time, however, the audio business is changing.

Dolan says, "The engineer of the future is an all-around

engineer.

The music engineer, as the industry has known it, is

on the decline." (qtd. in Jacobson, 1988, July, p. 172) Mike

Mancini (qtd. in Burger, 1988, December, p. 48) indicates that

engineers are going to have to know more about MIDI (Musical

Instrument Digital Interface), while Chan (1988, December) says,

"The change in operating methodologies based upon the workstation

concept will lay the foundation from which a new level of user-

friendly interfaces will be developed, and the subsequent job

Page 12

21

scope of the specialist will evolve into that of a generalist."

(p. 28)

The business which the industry engages in is also in a state

of flux.

Studio owner Chris Stone says, "The old 'diversity or

die' axiom is also important to profitability because the visual

business is still more profitable than the record business."

(qtd. in Burger, 1988, December, p. 44)

Chan (1988, December)

states that the new digital technologies will make this a more

viable opportunity.

He says, "Aside from the studio's main

business, many have integrated digital audio technologies with

their existing operations to offer audio-for-video services such

as off-line audio assembly, sweetening, audio post and layback."

(p. 26)

A possibility also exists that much of the new technology will

be implemented in studios outside the mainstream 'commercial'

applications.

Recording artist Patrick O'Hearn says,

"I think

that there will definitely be more progress made in the state-of-

the-art project/home recording studio." (qtd. in Burger, 1988,

December, p. 44)

How Should the Schools Respond?

Lambert (1989, July) starts a possible prioritized list by

stating, "Of greater importance [than technical skills] are the

people skills that set apart the seasoned engineer, producer or

musician from the individual new to the business."

(p. 14) David

Porter, of Music Annex (San Francisco, CA), adds,

".

I think

schools have to put students in real situations with clients."

Page 13

22

(qtd. in Jacobson, 1988, July, p. 72)

And Jones (1991, August)

would end the list by saying, "Finally, the modern educational

environment must empower everyone it touches to be successful in

a demanding, highly competitive changing marketplace by teaching

how to think, inductively and deductively, how to cope with the

increasing stress and pressures of our modern production

environment

.

.

."(p. 25)

Perhaps this is most eloquently

summarized by Hirsch (1985, Spring):

Still, history tells us that no person was considered educated

unless that education was well-rounded and without bias; a

place in time where Art and Science were taught as two

inseparable aspects of the same reality; where the best of

classical thought was preserved and integrated into the newest

discoveries; where being a whole person was considered to be

the highest virtue; where instructors were hired for their

real world achievements and where fellowship with students was

considered equally important with the specific knowledge

imparted in the classroom.

(n. pag.)

This reference to the first Renaissance comes as Hirsch calls for

a similar renaissance in the audio industry.

The schools, according to Alexander (1985, Spring) have two

major responsibilities, "It is our responsibility to prepare our

students with the necessary skills and to give them a realistic

expectation of what the field has to offer them."

(n. pag.) In

the area of necessary skills, Hirsch (1985, Spring) states, "The

total audio person must be able and ready to deal with every

Page 14

23

possible interface.

Moreover such a person must possess a depth

of knowledge and a flexibility of attitude that would facilitate

learning of new technologies not yet on-line." (pp.

1 & 2)

Realistic expectations come first through school training and

are then are reinforced by the internship experience.

The

groundwork for student expectations must include, according to

Stone (1992, February), the realization that, "Studio engineers

put in long hours for little pay.

Second or assistant engineers-

-where everyone inevitably starts out--are often no more than

glorified gofers or janitors, and even graduates of name

institutions are not assured of this position."

(p. 137)

And

Moylan (1988, December) adds that, "Very few of these people

[those in the U.S. audio industry and related fields] have

'glamour' jobs producing, tracking or mixing big-name artists.

In fact, many pro audio positions have no direct connection to

the creation or performance of music."

(p. 30) Thus, internship

experience of some kind is cited as a critical element in a

formal audio education.

Polon (1992b, August) asserts that,

"This [established internship program] is especially important

for four -year and some two-year programs where internships

provide both real world contact and 'a foot in the door.'"

(p.

111)

The role of the schools in preparing future audio industry

personnel is possibly best summed-up by Douds (1985, Spring):

Through better audio education everyone benefits: students

are

better prepared for the marketplace; studio

owners find better

Page 15

24

workers who are more productive; clients receive better

expertise for their money; and, in the long run, the consumer

benefits by receiving better engineered audio product, whether

that product is a record, cassette, compact disc, videotape

tv/radio commercial, film, etc.

(n. pag.)

Literature Related to Mail Survey Questionnaires

General

Much research in education is based on information obtained

through the use of a mail-survey questionnaire.

This data

collection process, like much that is conducted in the field of

education, falls under the category of survey research, which,

according to McMillan (1989), is defined as,

"The assessment of

the current status of opinions, beliefs, and attitudes by

questionnaires or interviews from a known population."

(p. 544)

The distinction to be made is that a mail-survey technique is

used.

Alreck (1985) says, "Perhaps the greatest advantage of the

mail survey is its ability to reach widely dispersed respondents

inexpensively."

(p. 44)

Erckis (1983) adds, "The distinction

between mail and other types of surveys is the fact that in

surveying by mail there is no person to ask the questions and

guide the respondent.

This gives rise to important differences

in survey design, questionnaire construction, and various other

aspects of the survey."

(p. 1)

A number of these considerations

are taken up at this juncture.

Page 16

25

Design Considerations

Most survey research takes a random sample of the population

as its subjects and uses the results to project results to the

entire population.

Alreck (1985) states, "The major reason for

sampling is economy.

To survey every individual in a population

using enumeration is ordinarily much too expensive in terms of

time, money, and personnel."

(p. 63)

He does not discount,

however, using enumeration, that is, surveying the entire

population.

One of the more pressing concerns in most mail-survey research

is the issue of nonresponse bias.

This kind of bias, according

to Alreck (1985) is, "A systematic affect on the data reducing

validity that results when those with one type of opinion or

condition fail to respond to a survey more often than do others

with different opinions or conditions."

(p. 414) It is not that

these people cannot respond but, rather, they will not respond.

Erdos (1983) describes the problem this way:

". . . when we speak

of a 'nonresponse problem,' we usually refer to people who can be

reached with proper and, if necessary, repeated effort and who

could answer our questions if they wanted to."

(p. 138)

Just what percentage of, returned questionnaires must be

attained to preclude nonresponse bias is a bit hazy, if not the

subject of a raging controversy.

Erdos (1983) emphatically

states, "No mail survey can be considered reliable unless it has

a minimum of 50 percent response, or unless it demonstrates with

some form of verification that the non-respondents are similar to

Page 17

the respondents." (p. 144)

Ereos does admit, however, that

findings from surveys with poorer response rates are occasionally

useful if no other data is available. (p. 145)

The other side of

the controversy is represented by Alreck (1985) who says, "The

single most serious limitation to direct mail data collection is

the relatively low response rate.

Mail surveys with response

rates over 30 percent are rare."

(p. 45) Alreck comes right back

to emphasize that the reliability depends on the sample obtained,

not on the number of surveys sent. (p. 45)

Perhaps one of the most important factors in ensuring a good

response rate is the actual questionnaire design.

Erdos (1983)

maintains that, "One of the main reasons for a respondent to

answer a questionnaire is the importance which he attaches to the

survey. If the questions look trivial or frivolous, the

researcher will lose some of his most intelligent respondents."

(p. 56) Sudman (1982) hastens to add that the look of the

questionnaire is of primary importance. He says, "The general

rule is that the questionnaire should look as easy as possible to

the respondent and should make the respondent feel that the

questionnaire has been professionally designed."

(p. 243)

There are a number of factors to consider when designing the

questionnaire document.

Erdos (1983) lists six:

1.

The questionnaire must include questions on all subjects

which are essential to the project; it should contain

all the important questions on these subjects, but none

which are not purposeful.

Page 18

27

2.

The questionnaire should appear brief and 'easy to

complete.' Reading it should not destroy this first

impression.

3.

The reader must be made to feel that he is participating

in an important and interesting project.

4.

The form should not contain any questions which could

bias the answers.

5.

It must be designed to elicit clear and precise answers

to all questions.

6. Phrasing, structure, and layout must be designed with

the problems of tabulating in mind.

The saving of time

and money in data processing should be one of the

considerations. (pp. 37-38)

Above all, according to ^,udman (1982), researchers should

consider themselves fortunate to have the cooperation of

respondents

He says, "Researchers are fortunate that almost all

persons are willing to donate their time and energy to providing

answers to a survey."

(p. 259) This being the case, he asserts,

they deserve a well designed questionnaire and a sincere 'thank

you.'

The respondents are the recipients of this planning through

the questions actually posed to them by the questionnaire

questions designed to gather data applicable to the project.

Sudman (1982) says, "Since questionnaires are designed to elicit

information from respondents, one of the criteria for the quality

of a question is the degree to which it elicits the information

Page 19

28

that the researcher desires.

This criterion is called validity."

(p. 17) Alreck (1985 adds, "The manner in which questions are

expressed can all too often introduce systematic bias, random

error, or both."

(p. 104)

It appears that one key variable is the level of threat

elicited by the question.

Sudman (1982) contends that, "Open-

ended questions that require writing more than a few words are

perceived as both difficult and potentially embarrassing because

of the possibility of making spelling or grammatical errors." (p.

218)

But if the information needed requires a fair number of

open-ended questions, Erdos (1983) predicts success only under

certain conditions, "Open-ended questions are frequently used in

mail surveys, but the successful use of this type of questioning

will depend on the nature of the question, the interest of the

respondent in the subject matter, and the education and literacy

of the group surveyed." (pp. 48 & 50)

Questions are not the only items printed on the questionnaire.

In addition to the questions and related instructions there are a

series of number codes, called precodes.

Sudman (1982) states,

"Precode all closed questions .o facilitate data processing and

to ensure that the data are in proper form for analysis." (p.

231)

Indeed, one of the traditional rationales for structured

questions is their amenability to coding.

Alreck (1985) advises,

"Listing such codes on the questionnaire before data collection

avoids the extremely laborious and time-consuming task of

'postcoding' the alternatives.

In fact, one of the major reasons

Page 20

2S

for using structured questions is the ability to precode the

alternatives." (p. 184)

A mail-survey questionnaire is accompanied by a letter.

Alreck (1985) explains the importance of the letter of

transmittal thus: "In the absence of personal contact and

interaction, the cover letter must explain the project and win

the cooperation of the recipient, and it must do so entirely on

its own."

(p. 206) So important is this letter that Erdos (1983)

insists that the percentage of returned questionnaires depends,

in large measure, on the effectiveness of this letter.

(p. 101)

Alreck (1985) states that the letter should be addressed to the

recipient in that, "Respondents are more likely to read a letter

that is addressed directly to them and appears to be hand typed

and signed than they are to a 'general' letter that is

unaddressed and obviously printed.

They are also more likely to

do what the 'personalized' letter requests."

(p. 209)

The contents of the letter must answer several questions that

the recipient is likely to ask.

Erdos (1983) lists twenty-two

items for the researcher to consider including in the letter:

1.

Personal communication.

2.

Asking a favor.

3.

Importance of the research project and its purpose.

4.

Importance of the recipient.

5.

Importance of the replies in general.

6.

Importance of the replies where the reader is not

qualified to answer most questions.

Page 21

7. How the recipient may benefit from this research.

8.

Completing the questionnaire will take only a short

time.

9.

The questionnaire can be answered easily.

10.

A stamped reply envelope is enclosed.

11.

How recipient was selected.

12.

Answers are anonymous or confidential.

13.

Offer to send report on results of survey.

14. Note of urgency-.

15.

Appreciation of sender.

16.

Importance of sender.

17.

Importance of the sender's organization.

18.

Description and purpose of incentive.

19. Avoiding bias.

20. Style.

21.

Format and appearance.

22. Brevity.

(p. 102)

Alreck (1985) reinforces these points with a useful twelve

question summary that could easily be converted into a checklist.

(p. 207)

One of Alreck's questions is, "When should I do it?"

Later he adds that, "Ordinarily over 95 percent of all returns

that will eventually be returned will be received within a period

of three or four weeks.'

(p. 217)

The mailing piece consists of the envelope, cover letter,

return envelope, and, sometimes, an inducement (Alreck 1985, p.

204)

With reference to the mailing envelope, Erdos (1983) says,

Page 22

31

"The name of the sender should appear neatly printed in the

corner of the envelope.

Good quality white paper, proper

addressing, and first-class postage (preferably stamped, rather

than metered) are all necessary in order to avoid any suggestion

that the contents of the envelope could possible be unwanted

mail."

(p. 118)

Postage is an important consideration with reference to both

mailing and return envelopes.

Alreck (1985) says, "The type and

amount of postage will affect the response rate.

The response

rate will be greatest when first class postage stamps are

affixed.

Response rate is least with a bulk mail permit, and

metered postage falls somewhere in between." (p. 206) But the

price to be paid for response rate must be weighed against its

importance.

Again, referring to postage, Alreck (1985) states,

"The use of first class postage stamps on return envelopes is a

costly technique.

It is not recommended unless it is important

to maximize response rate in every way possible." (p. 214)

One of the more frustrating aspects of mail surveys lies in

the area of undeliverables: mail which cannot be delivered due to

potential respondents moving and leaving no forwarding address or

forwarding addresses becoming dated.

Alreck (1985) asserts that

the percent of undeliverables is an indication of the quality of

the mail list that the researcher employed when designing the

sur ey.

(p. 217)

Data should be kept on the undeliverables.

Alreck (1985) states, "This information is not only useful to

assess the namelist quality, but it is also valuable to judge the

Page 23

32

potential quality and accuracy of the survey results and the

degree to which the sample will be representative of the

population as a whole."

(p. 255)

With so many factors to weigh, the researcher can easily make

a mistake which will affect the quality--and quantity--of the

data.

Erdos (1983) summarizes, "Some of the most common mistakes

of questionnaire construction occur because the researcher and

the respondent are not interested in the same things."

(p. 57)

Summary of Literature Reviewed

This review of literature has dealt with two major areas:

literature related to audio education and literature related to

mail-survey questionnaires.

The first area was restricted due to

the general lack of scientifically-based studies in this area.

Instead, it focused primarily on the 'trade' publications in an

effort to give a sense of the current status of audio education.

The second area focused only on those aspects of mail-survey

questionnaire construction germane to the present project.

An

overview of the major considerations follows.

The following conclusions pertaining to audio education

represent the principle findings which are relevant to the

present project:

1.

An in-house apprenticeship program is generally too costly,

requires too much time, and is too limiting in the type of

skills taught.

It is, therefore, a prohibitive undertaking

for the average studio.

The alternative is formal

education.

Page 24

3.3

2.

Schools need to focus on teaching students how to think in

order to enable them to solve the problems in the technical

world which is still on the drawing boards.

3.

Schools should teach students to operate the technology

with understanding.

4.

Schools should teach 'people skills.'

5.

Schools should provide students with

a realistic

expectation of what the industry is really like.

6.

Schools should use industry standard equipment.

7.

Schools should teach a diversity of audio applications.

8.

A long-term educational undertaking is

more likely to

achieve the above goals than

a short-term or seminar

course.

The following conclusions pertaining

to mail-survey

questionnaires represent the principle findings which

are

relevant to the present project:

1.

Although sampling is the usual approach, enumeration

(doing

a census survey) is feasible in some cases.

2.

A good rate of return is

necessary to mitigate against

nonresponse bias.

3.

The size of an acceptable rate of

return is controversial

but return rates of approximately 30%

appear adequate.

4.

Good return rates will be enhanced by: good

questionnaire

design, an effective letter of transmittal,

and a motivated

recipient.

Page 25

34

5. The success of extensive open-ended questioning is

dependent on the interest of the recipient.

6.

Precoding will enhance efficiency.

7.

Postage type is a consideration and will affect response

rate.

8.

The quality of the mailing list will be determined by the

quantity of undeliverables.

These conclusions, coupled with the rationale presented in

Chapter I, suggest a number of applications to the present

research.

It was with these conclusions in mind that the

questionnaire, cover letter, and mailing were designed. Also

suggested was the use of more open-ended questions that is normal

as a means to probe respondents for data beyond the limitations

set by the closed questions.

3 ;)

Page 26

CHAPTER III

Procedures

Description of Research Methodology

This nonexperimental, descriptive research was conducted to

survey employers in the professional audio industry to determine

their perceived value of audio education as well as their

perceived training needs.

The research used a mail-survey

questionnaire designed by the researcher to gather the data.

Research Design

As a means of answering the research questions stated in

Chapter I, the recipients of the questionnaire had to be

identified, the questionnaire and letter of transmittal designed,

the mailing executed, the data extracted from the returned

questionnaires, the data processed and analyzed, and the data

analysis reported.

Selection of Subjects

The professional audio industry is relatively small and,

therefore, also relatively easy to find.

This ease of location

is enhanced by the service nature of the industry and the

naturally related characteristic that the industry wants to be

found--by clients.

This study used two standard industry sources to locate the

potential respondents to the survey instrument.

They were: 1)

Mix Master Directory of the Professional Audio Industry (Act III,

1991); and 2) ®Billboard's 1991 International Recording Equipment

Page 27

36

and Studio Directory (BPI, 1990).

From these, only potential

respondents engaged in recording, production, and sound

reinforcement were selected since they were considered to be most

representative of the market for which Lansing Community College

trains.

This selection totaled 564 potential respondents.

Instrumentation

Data Collection

The data needed to answer the research questions were gathered

using a mail-survey questionnaire.

This questionnaire was sent

to every audio business engaged in recording, production, or

sound reinforcement in the eight state region chosen for study.

Development of the Questionnaire

The questionnaire used for this research was developed

specifically for this project.

No other research of this kind

was located and, therefore, there was not an existing

questionnaire designed specifically for this kind of research.

The general portions of the questionnaire are similar to any

number of questionnaires used for a variety of research.

The

remainder was formulated to address the research questions.

Revision of the Questionnaire

The questionnaire was reviewed by several people with respect

to format, relevance to the research, and compatibility with data

processing.

These people included: Dr. James C. Greene, Program

Director

Media Technology, Lansing Community College; Mrs.

Bonnie McGraw, Audio Lab Supervisor, Lansing Community College;

and Mr. Marc Smyth, Coordinator of TeleLearning, Lansing

Page 28

37

Community College.

Mr. Smyth's review was targeted towards the

data processing concerns.

Also, input was selected from members

of the local audio community who

were not on the mailing list for

the survey.

Suggestions made by Mr. Glenn Brown, Glenn

Brown

Productions, were received back in time

to be used in the

questionnaire design.

Input form the above individuals

was incorporated into the

draft version of the questionnaire.

It was this revised

questionnaire (see, Appendix A) which

was mailed to the potential

respondents on the compiled mailing list.

Administration of the Questionnaire

A cover letter (see, Appendix B)

was drafted to accompany the

questionnaire, and it,.the questionnaire,

and a postage-paid

return envelope were sent to the 564 potential

respondents on the

compiled mailing list.

The mailing was personally addressed

to

either the owner, chief engineer,

or studio manager.

The

recipients were asked to return the

questionnaire in the postage-

paid envelope by October 10, 1992.

No follow-up mailing was

planned due to financial constraints.

A total of 154 questionnaires (27.3%)

was returned.

A goal of

30% was selected for the optimum

return rate for the

questionnaire.

The small difference between the

returned

percentage and the goal was further

reason to forego the follow-

up mailing which is so often conducted for

a survey of this type.

Page 29

38

Data Processing and Analysis

As a pioneering research effort in this field, the

questionnaire asked for a mix of quantitative data and

qualitative responses.

Both the quantitative data and the

qualitative responses were placed in a database (Alpha Four) and

the quantitative data were then imported into a statistical

package (SPSSD for Windows')

.

The quantitative data were statistically reduced and the

results of these calculations are the subject of Chapter IV.

The

qualitative responses are reported by question number in

Appendices C through L, and are briefly summarized in Chapter IV.

Using the logical command structure provided by the database, the

qualitative data were sorted to generate a summary of comments

pertaining to a number of respondent characteristics (see,

Appendices M through S).

The conclusions to be drawn from these

sorts are also discussed briefly in Chapter IV.

Statistical operations were restricted to summary and

descriptive statistics.

No attempt was made to project the data

to the national population since there is no reason to believe

that the respondents from a restricted eight state region are

representative of the audio industry nationwide.

To have done so

would have required a random sample (or a census survey) to be

taken from that population rather than the more restricted

population addressed by this research.

Page 30

3ri

CHAPTER IV

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Introduction

This study was undertaken to determine how employers perceived

formal audio education, their training needs, how they judged

entry-level employees' qualifications, and the availability of

internships and entry-level employment.

The self-administered

mail-survey questionnaire was designed to gather this needed

data.

Questionnaires returned by respondents were complete to a

greater or lesser degree.

Some respondents chose not to respond

to all of the questions posed.

Others responded to all of the

closed questions but did not choose to respond to all of the

open-ended questions.

Still others not only responded to all of

the closed questions but were very helpful in responding-

sometimes at great length--to the open-ended questions.

Any failure to respond was taken as a 'no response' and not

included in the data analysis as other than a 'no response'.

Also, closed questions where more than one response was indicated

were treated in the same manner (as a 'no response').

Demographics

The first page of the questionnaire (questions 1

4) was

devoted to determining the nature of the facility that the

respondent was representing.

Question #1 asked for the business

activities of the respondents.

Page 31

40

Ql: Which descriptors represent your comparv's primary

business activities? (Please check J all that apply.)

Table 1 shows the ranking of the responses.

It should be

noted that respondents were encouraged to check more than one

response to indicate all of the business activities conducted at

their facility.

Table 1

PRIMARY BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF RESPONDENTS

Rank

Primary Business

Mean S.D. Freq.

1

Recording Studio

.675

.47 104 67.5

2

Production Co.

.396 .49 61 39.6

3

Audio Post Production

.260

.44 40 26.0

4

Remote Recording

.214 .41 33 21.4

5

Other.

.208 .41 32 20.8

6

Sound Reinf.

Local

.156 .36 24 15.6

7

Sound Reinf.

Regional

.149 .36 23

14.9

8

Remote Production

.136 .34

21 7.8

9

Multi-Image Production

.084 .28

13 8.4

10

Sound Reinf.

National

.078 .27

12

7.8

'See Appendix C for respondent's "Other" business activities.

Most of the respondents (67.5%) were engaged in the recording

business either as a primary activity, coordinate activity, or

subordinate activity.

Respondents engaged in production (39.6%)

and audio post (26.0%) combined to represent roughly the same

share of the responses (65.6%).

The data gathered from this question was further analyzed to

determine how many additional business activities the respondents

who were engaged in recording, audio post production, or sound

Page 32

41

reinforcement-local were conducting at their facilities.

Tables

2 through 4 represent this analysis.

Table 2 shows the business activities for respondents

indicating their facilities were involved in recording. Thirty-

five respondents (22.7%) represent businesses which are involved

solely in recording with no other business activities being

conducted at the facility (indicated by "0").

Twenty-six

respondents (16.9%) represent facilities involved in at least one

of the other primary businesses listed in question #1 (indicated

by "1").

The remainder were involved in as many as nine of the

other businesses along with recording.

The mean is 1.673

business activities (SD.1.923), median is 1.000, and the mode is

0.000.

The mode represents the 50 respondents (32.5%) who

indicated that their facility was not involved in recording in

any way.

Table 2

RECORDING STUDIO: NUMBER

OF BUSINESS ACTIVITIES

#

Freq.

0

35

22.7

1 26

16.9

2

18

11.7

3 11

7.1

4

3 1.9

5

5

3.2

6 3 1.9

7 1

.6

8

1

.6

9 1

.6

Page 33

Table 3 represents the same type of data analysis for those

respondents who indicated that their business was involved in

audio post production.

Here, only one respondent (0.6%)

represented a facility where audio post was the primary business

activity. All others were involved in up to nine of the other

primary business activities listed in question #1. The mean for

this category is 3.075 business activities (SD.2.105), median is

2.500, and the mode is 2.000.

Fully 114 respondents (74.0%) were

not involved in audio post in any way.

Table 3

AUDIO POST PRODUCTION:

NUMBER OF BUSINESS

ACTIVITIES

# Freq. %

0 1 .6

1

9 5.8

2

10 6.5

3 7 4.5

4

3 1.9

5

5

3.2

6

2 1.3

7 1 .6

8 1

.6

9 1

.6

Table 4 shows the sound reinforcement-local category.

In this

category, three (1.9%) of the respondents were involved in no

other business activities.

But, again, the respondents

represented facilities which were involved in as many as nine

additional business activities.

The mean was 3.208 (SD.2.502),

Page 34

4:3

the median was 3.000, and the mode 3.000.

Here, 130 respondents

(84.4%) were not involved in any way in sound reinforcement-local

activities.

Table 4

SOUND REINFORCEMENT-LOCAL:

NUMBER OF BUSINESS ACTIVITIES

#

Freq.

%

0

3

1.9

1 4 2.6

2 3

1.9

3

6 3.9

4 1 .6

5

3

1.9

6

1

.6

7

1 .6

8

1 .6

9 1

.6

Questions 2 through 4 were designed to determine how large

these facilities were by querying respondents about the number of

people who work at their facility.

Table 5 represents the data

on full-time employees (question #2).

Q2: How many people are employed full-time at your

facility?

Page 35

44

Table 5

FULL-TIME EMPLOYEES

Category Mean SD Freq.

1 3

.580

.495 87

58.0

4

6

.253 .436

38 25.3

7 10

.060 .238 9

6.0

10

25

.067

.250 10

6.7

Over 25

.040

.197

6 4.0

Of the 154 respondents, 150 (97.4%) provided data on the

number of full-time employees at their facility.

The data

indicate that 83.3% of the respondent's facilities do not employ

more than six individuals, and that over half (58.0%) do not

employ more than three.

Table 6 displays the data for part-time employees (question

#3).

Q3: How many people are employed part-part at your

facility?

Of the 154 respondents, 128 (83.1%) provided data on the

number of part-time employees at their facility.

Table 6

PART-TIME EMPLOYEES

Category

Mean

SD Freq.

%

1 3

.742 .439 95 74.2

4 6

.164 .372 21

16.4

7 10

.039 .195 5 3.9

10

25

.047 .212

6 4.7

Over 25

.008

.088 1 .8

Page 36

4F

Fully 90.6% of the respondent's facilities have six or fewer

part-time employees.

Further, almost three-quarters of them

(74.2%) have three or fewer part-timers.

Table 7 represents sub-contractors (question #4): Those

individuals who work in the facility on a per project basis and

do not receive a regular paycheck from the facility as either a

full-time or part-time employee.

Q4: How many sub-contractors (Independent Engineers,

Musicians, Programmers, etc.) do you employ each year at

your facility?

Of the 154 respondents, 143 (92.9%) provided data on the

number of independents, musicians, programmers and others who are

employed to work on specific projects.

Table 7

SUB-CONTRACTORS

Category

Mean SD

Freq.

1 3

.483

.501

69 48.3

4

6

.182

.387

26 18.2

7 10

.105

.307 15

10.5

10

25

.098

.298 14

9.8

Over 25

.140

.348 20 14.0

Here two-thirds (66.6%) employ six or fewer sub-contractors,

and almost half (48.3%) employ three or fewer.

From this demographic data the profile of the 'typical'

respondent is that he/she represents a recording studio which is

also engaged in one to two other audio business activities, has

three or fewer full-time employees, three or fewer part-time

Page 37

4f

employees, and retains three or fewer sub-contractors.

Research Question #1

The first of the four questions to be answered by this

research is: What value do employers place on formal education?

Fully seven of the questions on the questionnaire (9-12 & 17-19)

were framed to address this consideration.

First in the series of queries aimed at this issue is the

value placed on education when respondents are hiring an entry-

level employee or negotiating with a potential intern (question

#9)

.

Q9: When hiring an entry-level employee or an intern, what

factor is education?

Table 8 summarizes the responses.

Of the 154 respondents, 144

(93.5%) gave their rating of educational level.

The respondents

clearly consider educational level a factor with those not

sharing this view amounting to only 2.8% of those responding to

the question.

Table 8

EDUCATIONAL LEVEL PREFERENCE

Level

Mean

SD Freq.

Most Important

.049 .216 7 4.9

Very Much A Factor

.451

.499 65

45.1

Just A Factor

.472 .501

68

47.2

Not A Factor

.028

.164 4 2.8

One hundred fourteen (74.0%) of the respondents rated their

desired level of education (question #10).

Page 38

47

Q10: If education IS a factor, what level is most desirable

to you?

Table 9 summarizes the responses.

Table 9

DESIRED EDUCATIONAL LEVEL

Level

Mean

SD

Freq.

Certificates .167

.374

19

16.7

Trade School .289

.456

33

28.9

Associate's :184

.389

21

1.8.4

Bachelor's

.500

.502

57

50.0

The Bachelor's degree is perceived as the educational level of

choice from these respondents.

Trade school ranks second, with

Certificates and the Associate's degree coming in last.

Question #11 asked respondents to rank their preferences for

the discipline which the degree represents.

Q11: If you answered Associate's or Bachelor's above, in

what discipline? (If necessary, check / more than one

choice.)

Table 10 shows that ranking.

Here, of those who specified the

Associate's or Bachelor's degree in question #10 (n=78), seventy-

six (97.4%) ranked the disciplines listed or specified "Other."

Page 39

48

Table 10

RANK-ORDERED DISCIPLINES FOR

ASSOCIATE'S OR BACHELOR'S DEGREE

Rank

Discipline

Mean S.D. Freq. %

Actual

1

Music

.513

.503 39 51.3

22.8

2

Sound .408 .495 31 40.8 18.1

3 Electrical

.289

.457 22 28.9

12.9

Engineering

4

Recording Industry

.289 .457 22 28.9 12.9

Mgmt.

5

Media Technology

.276

.450 21

27.6 12.3

6

Other'

.158 .367 12 15.8

7.0

7 Business

.158 .367

12 15.8

7.0

8

Media Arts

.118

.325

9

11.8

5.3

9 Physics

.039

.196

3

3.9 1.8

'See Appendix D for respondent's "Other" preferred disciplines.

Since the respondents were allowed to list more than one

choice, the percentages do not add to 100%.

There were 171

choices made by the 76 respondents who were qualified (by

answering A:.:lociate's or Bachelor's to question #10) to respond

to this portion of the questionnaire.

Although Music ranked first, its actual percentage (22.8%) is

not large enough to indicate a clear preference.

Sound is next

(18.1%) with Electrical Engineering, Recording Industry

Management, and Media Technology close to a tie (12.9%, 12.9%,

and 12.3%, respectively).

The next question (#12) sought a rating of superiority between

the four-year degree and the two-year degree.

Page 40

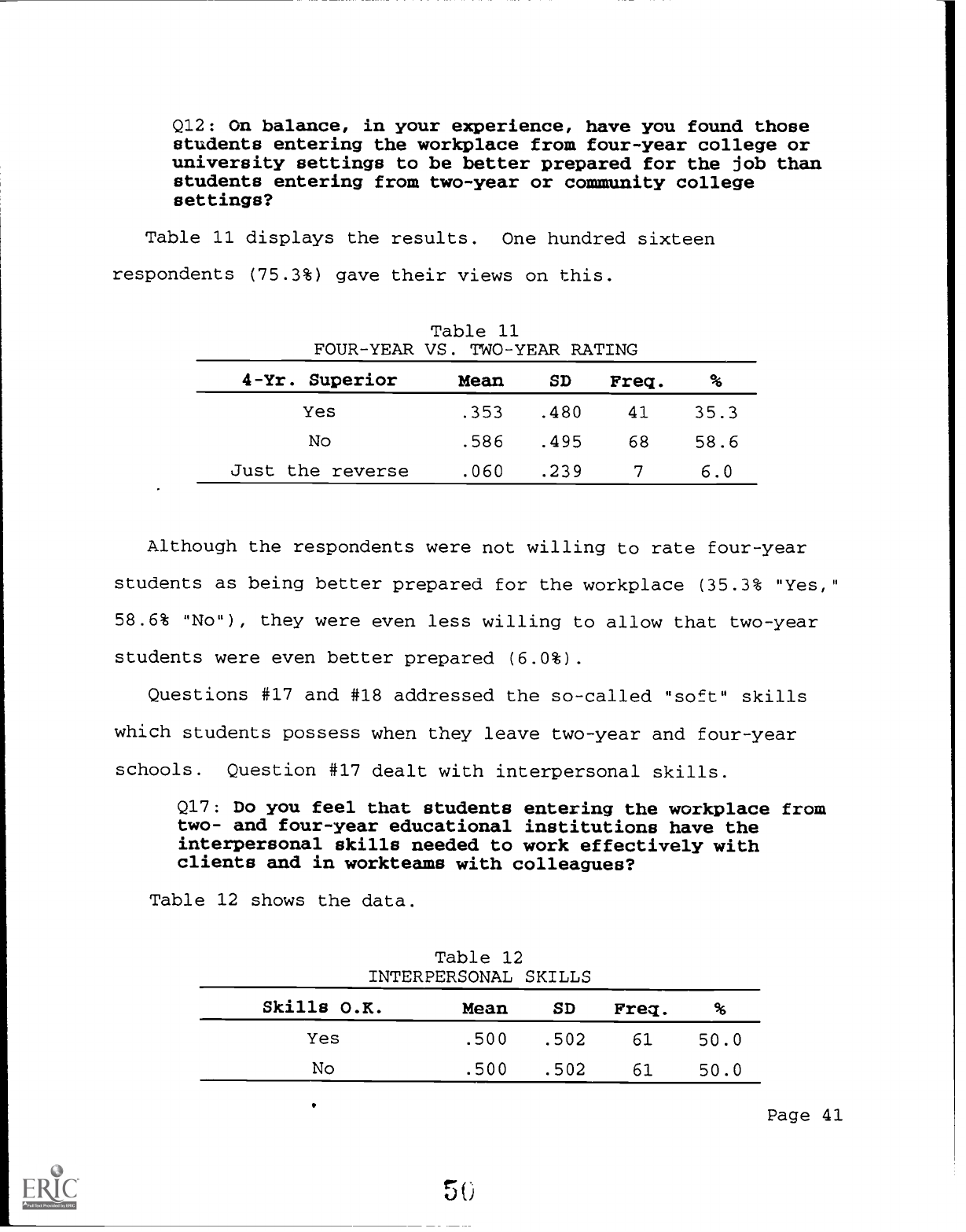

Q12: On balance, in your experience, have you found those

students entering the workplace from four-year college or

university settings to be better prepared for the job than

students entering from two-year or community college

settings?

Table 11 displays the results.

One hundred sixteen

respondents (75.3%) gave their views on this.

Table 11

FOUR-YEAR VS. TWO-YEAR RATING

4-Yr. Superior

Mean

SD

Freq.

Yes

.353 .480

41 35.3

No

.586 .495

68 58.6

Just the reverse

.060 .239

7 6.0

Although the respondents were not willing to rate four-year

students as being better prepared for the workplace (35.3% "Yes,"

58.6% "No"), they were even less willing to allow that two-year

students were even better prepared (6.0%).

Questions #17 and #18 addressed the so-called "soft" skills

which students possess when they leave two-year and four-year

schools.

Question #17 dealt with interpersonal skills.

Q17: Do you feel that students entering the workplace from

two- and four-year educational institutions have the

interpersonal skills needed to work effectively with

clients and in workteams with colleagues?

Table 12 shows the data.

Table 12

INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

Skills O.K.

Mean SD

Freq.

Yes

No

.500

.500

.502

.502

61

61

50.0

50.0

Page 41

One hundred twenty-two (79.2%) of the respondents gave a

response.

There was a clear 50-50 split on the issue of good

interpersonal skills. See Appendix I for the comments of

respondents who answered "No."

The communication skills of two-year and four-year graduates

were the substance of question #18.

Q18: Do you feel that students entering the workplace from

two- and four-year educational institutions have writing

and verbal communication skills that are adequate to ensure

their success in the audio industry?

This question addressed both written and verbal skills.

Table

13 summarizes the responses.

Table 13

COMMUNICATION SKILLS

Skills O.K.

Mean

SD Freq.

Yes

No

.659

.341

.476

.476

81

42

65.9

34.1

One hundred twent\--three respondents (79.9%) gave their

perceptions on this issue.

Clearly--by a two-to-one ratio--they

thought that verbal and written communications skills were at the

level required to function in the workplace.

The comments of

those who thought communication skills were substandard (34.1%)

are listed in Appendix J.

The last question to deal with research question #1 is survey

question #19.

This question permitted respondents to make any

general comments that they wanted the post-secondary schools to

Page 42

be aware of.

Of the 154 respondents, 66 (42.9%) said they wanted

to make comments not allowed for elsewhere.

These comments are

listed in Appendix K.

The comments they gave will be discussed

along with the qualitative data from the other survey questions

in a later section of this chapter.

Research Question #2

The second of the four questions to be answered by this

research is: What are the rank-ordered training needs of

employers?

Three questionnaire questions pertained to this

question,

They are questions #14, #15, and #16.

Question #14 asked respondents to prioritize training areas

which they thought entry-level employees should be conversant

with.

Q14: Please prioritize the training areas in which you feel

a potential employee should receive pre-employment

training. (Number from 1-4

,

with "1" being the highest

priority.)

The data is displayed in Table 14.

Page 43

Table 14

TRAINING AREAS

Rank

Training Areas Mean

S.D.

1

Console

2.050 1.827

2

Analog Multi-Track

2.683 2.525

3 Microphones 2.986

2.662

4

Signal Processing Gear 3.302

2.544

5 MIDI Instruments/Controllers 4.043

3.633

6 Digital Multi-Track 4.058 3.961

7

Digital Workstation

4.129 4.118

8

Monitor Mixer

4.165 4.301

9

Synchronization System 4.173 3.899

10

Computers

4.338

3.661

11

Console Automation

4.446 4.301

12

Duplication Equipment

5.014

4.703

It will be noted that the traditional studio complement of

equipment occupies the top four positions.

The

recording/production/sound reinforcement console is first with

the ancillary gear following on the heels (analog multi-track,

microphones, and signal processing gear).

In this prioritization

18 (11.7%) of the respondents made no ranking.

Question #15 was posed to respondents just in case question

#14 did not cover everything that was on their minds.

Q15: Are there any other areas in which you feel students

should receive pre-employment training as part of a formal

educational program?

Here, respondents were able to list other areas where they

felt training should be focused.

Table 15 shows the break

between those who wanted to add and those who didn't.

Page 44

Table 15

ADDITIONAL TRAINING AREAS

More Training