National Transportation

Safety Board

Washington, D.C. 20594

OFFICIAL BUSINESS

Penalty for Private Use, $300

PRSRT STD

Postage & Fees Paid

NTSB

Permit No. G-200

In-Flight Engine Failure and Subsequent

Ditching

Air Sunshine, Inc., Flight 527

Cessna 402C, N314AB

About 7.35 Nautical Miles West-Northwest of

Treasure Cay Airport, Great Abaco Island,

Bahamas

July 13, 2003

Aircraft Accident Report

NTSB/AAR-04/03

PB2004-910403

Notation 7671A

National

Transportation

Safety Board

Washington, D.C.

National

Transportation

Safety Board

Washington, D.C.

this page intentionally left blank

Aircraft Accident Report

In-Flight Engine Failure and Subsequent

Ditching

Air Sunshine, Inc., Flight 527

Cessna 402C, N314AB

About 7.35 Nautical Miles West-Northwest of

Treasure Cay Airport, Great Abaco Island,

Bahamas

July 13, 2003

NTSB/AAR-04/03

PB2004-910403 National Transportation Safety Board

Notation 7671A 490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W.

Adopted October 13, 2004 Washington, D.C. 20594

E

P

L

U

R

I

B

U

S

U

N

U

M

N

A

T

I

O

N

A

L

T

R

A

S

P

O

R

T

A

T

I

O

N

B

O

A

R

D

S

A

F

E

T

Y

N

National Transportation Safety Board. 2005. In-Flight Engine Failure and Subsequent Ditching, Air

Sunshine, Inc., Flight 527, Cessna 402C, N314AB, About 7.35 Nautical Miles West-Northwest of

Treasure Cay Airport, Great Abaco Island, Bahamas, July 13, 2003. Aircraft Accident Report

NTSB/AAR-04/03. Washington, DC.

Abstract: This report explains the accident involving Air Sunshine, Inc., flight 527, a Cessna 402C,

which experienced an in-flight engine failure and was subsequently ditched about 7.35 nautical

miles west-northwest of Treasure Cay Airport, Great Abaco Island, Bahamas. The safety issues

discussed in this report include maintenance record-keeping and practices, pilot proficiency,

Federal Aviation Adminstration (FAA) oversight, and emergency briefings. A safety

recommendation concerning emergency briefings is addressed to the FAA.

The National Transportation Safety Board is an independent Federal agency dedicated to promoting aviation, railroad, highway, marine,

pipeline, and hazardous materials safety. Established in 1967, the agency is mandated by Congress through the Independent Safety Board

Act of 1974 to investigate transportation accidents, determine the probable causes of the accidents, issue safety recommendations, study

transportation safety issues, and evaluate the safety effectiveness of government agencies involved in transportation. The Safety Board

makes public its actions and decisions through accident reports, safety studies, special investigation reports, safety recommendations, and

statistical reviews.

Recent publications are available in their entirety on the Web at <http://www.ntsb.gov>. Other information about available publications also

may be obtained from the Web site or by contacting:

National Transportation Safety Board

Public Inquiries Section, RE-51

490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W.

Washington, D.C. 20594

(800) 877-6799 or (202) 314-6551

Safety Board publications may be purchased, by individual copy or by subscription, from the National Technical Information Service. To

purchase this publication, order report number PB2004-910403 from:

National Technical Information Service

5285 Port Royal Road

Springfield, Virginia 22161

(800) 553-6847 or (703) 605-6000

The Independent Safety Board Act, as codified at 49 U.S.C. Section 1154(b), precludes the admission into evidence or use of Board reports

related to an incident or accident in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report.

iii Aircraft Accident Report

Contents

Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .v

Abbreviations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vi

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vii

1. Factual Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

1.1 History of Flight . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

1.2 Injuries to Persons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

1.3 Damage to Airplane . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.4 Other Damage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.5 Personnel Information. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.5.1 The Pilot . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.5.1.1 Flight Check History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

1.5.2 The Director of Maintenance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

1.5.3 The Assistant Mechanic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

1.6 Airplane Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

1.6.1 Engines and Propellers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

1.6.1.1 Air Sunshine’s Approved Aircraft Inspection Program. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

1.6.1.2 Differential Compression Checks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.6.1.2.1 June 12 to 14, 2003, Differential Compression Checks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.6.1.3 Time Between Overhauls. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

1.7 Meteorological Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

1.8 Aids to Navigation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

1.9 Communications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

1.10 Airport Information. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

1.11 Flight Recorders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

1.12 Wreckage and Impact Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

1.12.1 General . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

1.12.2 Engines and Propellers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

1.13 Medical and Pathological Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

1.14 Fire . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

1.15 Survival Aspects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

1.15.1 General . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

1.15.2 Emergency Briefings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

1.15.3 Personal Flotation Devices. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

1.15.4 Search and Rescue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

1.16 Tests and Research . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

1.16.1 Cessna Airplane Performance Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

1.16.2 Airplane Performance Study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

1.16.3 Metallurgical Inspections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

1.16.3.1 Right Engine Cylinder Assemblies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

1.16.3.2 Right Engine Pistons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

1.16.3.3 Right Engine Crankcase. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Contents iv Aircraft Accident Report

1.16.3.4 Right Engine No. 2 Cylinder Hold-Down Studs and Through Bolts . . . . . . . . . 27

1.16.3.5 Cylinder Hold-Down Nuts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

1.17 Organizational and Management Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

1.17.1 Air Sunshine. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

1.17.1.1 Air Sunshine’s In-Flight Engine Failure Procedures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

1.17.1.2 Ditching Procedures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

1.17.1.3 Company Record-Keeping. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

1.17.1.3.1 Maintenance Records . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

1.17.1.3.2 Aircraft Flight Logs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

1.17.2 Federal Aviation Administration Oversight. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

1.17.2.1 General. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

1.17.2.2 San Juan Flight Standards District Office Preaccident

Oversight of Air Sunshine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

1.17.2.3 Fort Lauderdale Flight Standards District Office

Postaccident Oversight of Air Sunshine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

1.17.2.4 San Juan Flight Standards District Office Postaccident

Oversight of Air Sunshine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

1.17.2.5 Additional Postaccident Actions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

1.18 Additional Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

1.18.1 Previous Ditching Accidents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

2. Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

2.1 General . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

2.2 Accident Sequence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

2.3 Airplane Performance After the Right Engine Failure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

2.4 Right Engine Failure Sequence. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

2.5 Cause of the Loosened No. 2 Cylinder Hold-down Nuts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

2.6 Air Sunshine Maintenance Record-Keeping and Practices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

2.7 Pilot Proficiency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

2.8 Pilot Failure to Use Shoulder Harness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

2.9 Emergency Briefings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

3. Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

3.1 Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

3.2 Probable Cause . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

4. Recommendation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

5. Appendix

A: Investigation and Public Hearing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

v Aircraft Accident Report

Figures

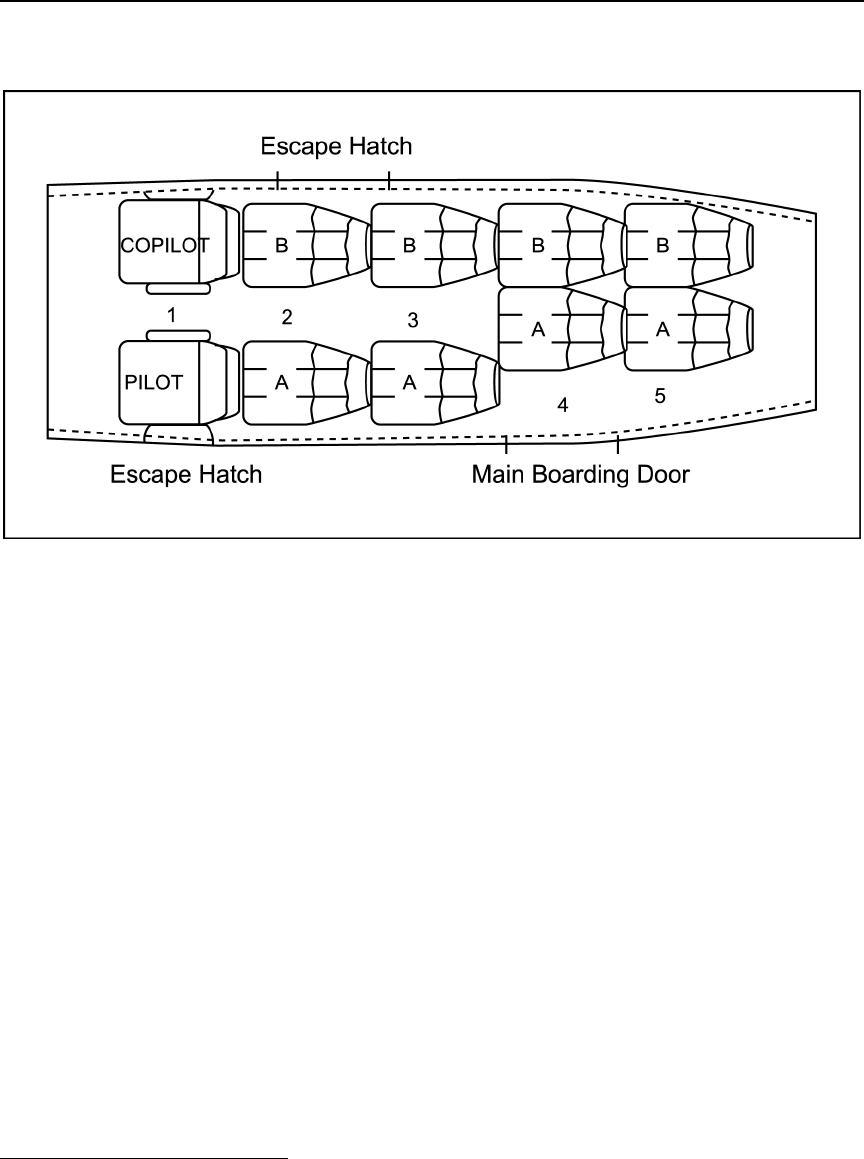

1. Interior configuration of the accident airplane. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

2. Cylinder differential compression check form.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

3. Exterior of the upper outboard engine cowling. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

4. The condition in which the right engine No. 2 cylinder

retention system components were found. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

vi Aircraft Accident Report

Abbreviations

A&P airframe and powerplant

AAIP Approved Aircraft Inspection Program

ARTCC air route traffic control center

ATP airline transport pilot

CFI certified flight instructor

CFR Code of Federal Regulations

CG center of gravity

CVR cockpit voice recorder

F Fahrenheit

FAA Federal Aviation Administration

FDR flight data recorder

FLL Fort Lauderdale/Hollywood International Airport

fpm feet per minute

FSDO Flight Standards District Office

Hg mercury

KIAS knots indicated airspeed

METAR meteorological aerodrome report

MYAT Treasure Cay Airport

MYGF Grand Bahamas International Airport

PFD personal flotation device

PIC pilot-in-command

PMI principal maintenance inspector

psi pounds per square inch

PTRS Program Tracking and Recording System

SB service bulletin

SJU Luis Munoz Marin International Airport

SRQ Sarasota/Bradenton International Airport

TBO time between overhaul

TCM Teledyne Continental Motors

TSO Technical Standard Order

vii Aircraft Accident Report

Executive Summary

On July 13, 2003, about 1530 eastern daylight time, Air Sunshine, Inc. (doing

business as Tropical Aviation Services, Inc.), flight 527, a Cessna 402C, N314AB, was

ditched in the Atlantic Ocean about 7.35 nautical miles west-northwest of Treasure Cay

Airport (MYAT), Treasure Cay, Great Abaco Island, Bahamas, following the in-flight

failure of the right engine. Four of the nine passengers sustained no injuries, three

passengers and the pilot sustained minor injuries, and one adult and one child passenger

died after they evacuated the airplane. The airplane sustained substantial damage. The

airplane was being operated under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations

Part 135 as a scheduled international passenger commuter flight from Fort

Lauderdale/Hollywood International Airport, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to MYAT. Visual

meteorological conditions prevailed for the flight, which operated on a visual flight rules

flight plan.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of

this accident was the in-flight failure of the right engine and the pilot’s failure to

adequately manage the airplane’s performance after the engine failed. The right engine

failure resulted from inadequate maintenance that was performed by Air Sunshine’s

maintenance personnel during undocumented maintenance. Contributing to the passenger

fatalities was the pilot’s failure to provide an emergency briefing after the right engine

failed.

The safety issues discussed in this report include maintenance record-keeping and

practices, pilot proficiency, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) oversight, and

emergency briefings. A safety recommendation concerning emergency briefings is

addressed to the FAA.

this page intentionally left blank

1 Aircraft Accident Report

1. Factual Information

1.1 History of Flight

On July 13, 2003, about 1530 eastern daylight time,

1

Air Sunshine, Inc. (doing

business as Tropical Aviation Services, Inc.),

2

flight 527, a Cessna 402C, N314AB, was

ditched in the Atlantic Ocean about 7.35 nautical miles west-northwest of Treasure Cay

Airport (MYAT), Treasure Cay, Great Abaco Island, Bahamas, after the in-flight failure of

the right engine. Two of the nine passengers

3

sustained no injuries, five passengers and the

pilot sustained minor injuries, and one adult and one child passenger died after they

evacuated the airplane.

4

The airplane sustained substantial damage. The airplane was

being operated under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 135 as

a scheduled international passenger commuter flight from FLL to MYAT.

5

Visual

meteorological conditions prevailed for the flight, which operated on a visual flight rules

flight plan.

The accident pilot was scheduled to fly the accident airplane on a 2-day trip

sequence, which began about 0900 on July 12, 2003. The pilot flew five flights, each of

which lasted about 1 hour, on the first day of the trip sequence. The last flight was from

FLL to Sarasota/Bradenton International Airport (SRQ), Sarasota, Florida, and it arrived

at SRQ about 1930. All of the first day’s flights were uneventful, and the pilot reported no

engine- or airframe-related discrepancies for any of the flights.

On July 13, 2003, the pilot arrived at SRQ about 0830 for the second day of the

trip sequence. The pilot was scheduled to conduct five flights, each of which was to last

about 1 hour. The first flight departed SRQ about 0930 and arrived at FLL about 1030.

The second flight departed FLL about 1100 and arrived at MYAT about 1200. The third

1

Unless otherwise indicated, all times in this report are eastern daylight time. The airplane was not

equipped with a cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and was not required to be so equipped. Therefore, all times

referenced in this report are approximations, except for the takeoff time, which was determined by reference

to transcripts of voice recordings obtained from the Fort Lauderdale/Hollywood International Airport (FLL)

air traffic control tower and the Miami Automated International Flight Service Station.

2

Air Sunshine and Tropical Aviation Services are two separate companies owned and operated by the

same people.

3

Four of the nine passengers were children; one of the children was under 2 years of age and was

seated on an adult passenger’s lap during the flight.

4

The search for, and rescue of, the surviving airplane occupants (and recovery of the bodies of the two

other airplane occupants) is discussed in section 1.15.4.

5

Under the provisions of Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, the

investigation of an airplane crash is the responsibility of the state of occurrence (the state or territory in

which an accident or incident occurs, which in this case was the Bahamas). However, the state of occurrence

may delegate all or part of an investigation to another state by mutual arrangement or consent. At the request

of the Bahamian Government, the National Transportation Safety Board assumed full responsibility for the

investigation. The Bahamian Government designated an accredited representative to the investigation.

Factual Information 2 Aircraft Accident Report

flight departed MYAT about 1215 and arrived at FLL about 1330. All of the flights were

reported to be uneventful.

The pilot stated that, before departing on the fourth flight of the day, from FLL to

MYAT, he conducted a preflight inspection of the airplane, which included checking the

oil quantity. The accident flight was cleared for takeoff at 1427:11 and was estimated to

last about 1 hour 10 minutes.

During postaccident interviews, passengers stated that, before starting the engines,

the pilot briefed

6

them on the location of the personal flotation devices (PFD),

7

the exits,

and the safety briefing cards

8

and on the need to keep their lapbelts fastened during the

flight. One of the passengers who accompanied a child noted that the pilot’s briefing did

not include how to handle children during an emergency and added that the briefing was

“short and rushed.”

The pilot and adult passengers stated that the cruise portion of the flight was

uneventful, and the pilot stated that the engine instruments showed no indications of a

mechanical problem. The pilot indicated that the flight’s cruise altitude was about

7,500 feet and that the cruise speed was about 160 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS).

9

The pilot stated that, during the descent into MYAT, he maintained the same power

setting that he used during cruise flight, which was about 2,300 rpm and 27 inches of

mercury (Hg) manifold pressure. The pilot stated that, about 20 to 25 miles from MYAT

(about 45 to 50 minutes into the flight), while descending to about 3,500 feet, he heard a

bang and saw oil coming out of the right engine cowling.

10

The adult passenger in the copilot’s seat (the seat to the right of the pilot seat)

reported seeing a “stream of oil” coming from the right engine and stated that he notified

the pilot of his observation. Several of the other adult passengers reported seeing white

smoke coming from the right engine. These passengers stated that the smoke was followed

6

Title 14 CFR 135.117(a) requires pilots to brief passengers orally before departure.

Section 135.117(a) states that the predeparture briefing should include, in part, information on the use of

safety belts, the location of and instructions for opening the passenger entry door and emergency exits, and

the location of survival equipment.

7

The airplane was equipped with 10 PFDs that were sealed in plastic pouches. Eight of the PFDs were

stowed under the forward edge of each passenger seat. The PFDs for the pilot and copilot positions were

stowed outboard of each pilot seat. For more information, see section 1.15.3.

8

The safety briefing cards were contained in the stowage pockets located on the back of each seat.

9

The airplane was not equipped with a flight data recorder (FDR) and was not required to be so

equipped. Data from the Nassau Air Route Surveillance Radar (about 125 miles south of the accident

site) did not indicate any targets in the Bahamas airspace consistent with the reported route and altitude of

flight 527. Other aircraft were observed at an altitude of about 6,600 feet and above near Grand Bahamas

Island and at an altitude of about 5,100 feet and above near the ditching site. All flight altitudes and speeds

referenced in the report are based on the pilot’s recollections.

10

From June 12 to 14, 2003, Air Sunshine’s Director of Maintenance and an assistant mechanic

performed differential compression checks on the accident airplane’s right engine cylinders during the

airplane’s last recorded engine maintenance. For more information about these checks, see section 1.6.1.2.1.

Factual Information 3 Aircraft Accident Report

by a stream of oil and then the sound of a loud bang. They reported seeing parts falling

from the engine after they heard the loud bang.

The pilot stated that, after he heard the bang, he reduced power to the right engine.

The pilot indicated that, at the time of the event, the airplane’s airspeed was about 135 to

140 KIAS. He added that the airspeed for a normal descent should be about 140 knots.

The pilot stated that he then saw that the engine magnetos had penetrated through the

engine cowling and that the magnetos were hanging from wires. He added that he did not

see any other damage. He stated that he noticed that the right engine oil pressure

indication was decreasing rapidly. He added that the fuel selector was “in the green” (that

is, each engine was being provided fuel from its respective main fuel tank). He stated that

he attempted to feather

11

the right propeller and shut down the engine

12

but that the

propeller continued “wind-milling” (turning) slowly. The passenger in the copilot seat and

the adult passenger in the seat behind the copilot’s seat also reported that the pilot tried to

feather the right propeller but that it continued to turn after the engine failed.

13

The pilot stated that, after he attempted to shut down the right engine, he applied

full power to the left engine and tried to fly the airplane but that he could not maintain

altitude. He stated that he slowed the airplane to “blue line” (single-engine best climb rate)

airspeed, which is about 105 KIAS, and that, at that point, the airplane was at a descent

rate of about 200 to 300 feet per minute (fpm).

The pilot stated that he contacted Air Sunshine’s station manager at MYAT after

trying to shut down the engine. The station manager stated that the pilot told him that the

right engine had failed and that he was at an altitude of about 3,000 feet. The manager

added that the pilot asked him to contact the company’s Director of Operations at FLL,

which the manager did. Air Sunshine’s Director of Operations told the manager to ask the

pilot if the propeller on the failed engine was feathered, and the pilot responded that it

was. The Director of Operations then asked the manager to get the airplane’s distance

from the airport, altitude, and descent rate; the pilot responded that he was about 15 miles

from the airport

14

at an altitude of about 2,000 feet with a descent rate of about 200 fpm.

The Director of Operations instructed the manager to tell the pilot to “keep the good

engine at full power, bank to the good engine and to just stay calm and fly the plane.” The

pilot told the manager that he had already “done all of those things.”

11

Feathering means to rotate the propeller blades so that the blades are parallel to the line of flight to

reduce drag and prevent further damage to an engine that has been shut down.

12

The pilot stated that he did not follow Air Sunshine’s procedures for an in-flight engine failure

because he knew which engine had failed; therefore, he chose to immediately shut down the right engine. He

added that he did not follow the engine failure checklist because he was “too busy flying the airplane.” For

more information about Air Sunshine’s in-flight engine failure procedures, see section 1.17.1.1.

13

The pilot and both passengers reported that the right propeller continued turning until the airplane

contacted the water.

14

The airplane was equipped with a global positioning system, which the pilot used to determine the

airplane’s distance from the airport.

Factual Information 4 Aircraft Accident Report

The station manager stated that he then alerted local agencies about the emergency

and instructed another Air Sunshine pilot, who had just taken off from Marsh Harbor,

Bahamas, for FLL, to divert that flight toward flight 527 and follow the airplane until it

reached the airport. The Air Sunshine pilot transmitted a distress call for flight 527, which

the pilot of a nearby flight (Gulf flight 9267) heard and relayed to the Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA) Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC), Miami, Florida.

The pilot stated that, after talking to the station manager, he slowed the airplane to

about 95 KIAS to try to maintain altitude. The pilot stated that, once he descended from

about 1,500 to 1,000 feet, he realized the airplane could not make it to the airport and that

he would have to ditch the airplane. The pilot stated that he ditched the airplane parallel to

the waves with the flaps retracted. He added that, at the time of the ditching, the winds

were about 15 knots, and the outside air temperature was about 80° to 90° Fahrenheit (F).

The passenger in the copilot seat stated that the pilot did a good job ditching the airplane.

He stated that he noticed a placard on the instrument panel with instructions for ditching,

which stated that the airspeed should be kept in the “blue zone,” and that the airspeed was

within this zone during the ditching. Adult passengers described the contact with the water

as “very hard.” They stated that the airplane landed “flat” and that it did not dive into the

water.

During postaccident interviews, the passengers stated that the pilot did not instruct

them to retrieve their PFDs or to assume a brace position before contact with the water.

The passengers stated that the only time the pilot addressed them after the right engine

failed and before the airplane contacted the water was to tell them to “calm down.”

The airplane was located at 26° 45.547' north latitude and 77° 31.642' west

longitude. The accident occurred during daylight hours.

1.2 Injuries to Persons

Injuries Flight Crew Cabin Crew Passengers Other Total

Fatal 00 202

Serious 00 000

Minor 10 506

None 00 202

Total 10 9010

Factual Information 5 Aircraft Accident Report

1.3 Damage to Airplane

The airplane sustained substantial damage.

1.4 Other Damage

No other damage was reported.

1.5 Personnel Information

1.5.1 The Pilot

The pilot, age 46, was hired by Air Sunshine in September 1995. He held an airline

transport pilot (ATP) certificate, which was issued March 7, 1998, with a multiengine land

rating. Additionally, he held a commercial pilot certificate with a single-engine land rating

and a certified flight instructor (CFI) certificate with single-engine, multiengine, and

instrument ratings. The pilot held an FAA first-class medical certificate, dated June 9,

2003, with no limitations.

According to the pilot, he began flight training at Aviation Training, Hayward,

California. The pilot reported that, before he began working for Air Sunshine, he worked as a

first officer on Embraer 110 airplanes for Payam Aviation Services, Tehran, Iran, for 2 years.

The pilot began working for Air Sunshine in September 1995, performing clerical

work for about 6 months before starting the company’s flight training. He served as first officer

on the company’s Embraer 110 for about 1 1/2 years, during which time he earned his ATP

certificate. In 1998, he upgraded to captain on the Cessna 402. He resigned from Air Sunshine

on September 29, 2002. From September 30 to November 11, 2002, the pilot received flight

training at Arrow Air, Inc., in Miami.

15

The pilot left Arrow Air because he could not

complete the training.

16

On November 23, 2002, the pilot was rehired by Air Sunshine.

Air Sunshine records indicated that the accident pilot had accumulated a total

flying time of about 8,000 hours, about 5,500 hours of which were as pilot-in-command

(PIC) and about 5,000 hours of which were in Cessna 402 airplanes. He had flown

about 251, 69, 13, and 6 hours in the last 90, 30, and 7 days, and 24 hours, respectively.

The pilot’s last PIC line check occurred on July 9, 2002; his last PIC proficiency check

occurred on January 14, 2003; and his last recurrent ground training occurred on June 14,

2003. A search of FAA records found no evidence of enforcement actions.

15

Arrow Air is a 14 CFR Part 121 supplemental all-cargo air carrier. During the time that the pilot was

in training, the company operated McDonnell Douglas DC-8 and Lockheed L-1011 airplanes.

16

A review of Arrow Air’s simulator training records for the pilot revealed that he had received a large

number of “unsatisfactory” grades. Further, the records indicated that the pilot needed to improve his

scanning and checklist skills, including response and organization.

Factual Information 6 Aircraft Accident Report

FAA records revealed that the pilot had been involved in an incident on June 12,

1999, in which the nose landing gear collapsed during landing at FLL. The pilot and

passengers were not injured, and the airplane sustained minor damage. The records also

revealed that the pilot was involved in an accident on March 16, 2000, in which a tire

failed during takeoff from FLL.

17

The pilot aborted the takeoff but was unable to keep the

airplane on the runway. The pilot and passengers were not injured, and the airplane

received substantial damage. Further, a review of the FAA’s Program Tracking and

Reporting System (PTRS) records revealed that, on September 13, 2000, the pilot failed a

ramp check because his airplane was found to have numerous discrepancies and his

passenger briefing was found to be inadequate.

As previously stated, the pilot was scheduled for a 2-day trip sequence on July 12

and 13, 2003. Between 0900 and 1700 on July 12th, the pilot flew five flights and

accumulated about 5 hours of flight time. All of the flights were conducted in the accident

airplane. The pilot stated that, after the last flight (FLL to SRQ), he ate, watched some

television, and went to bed between about 2230 and 2300.

The pilot stated that he awoke about 0730 on July 13th and arrived at SRQ

about 0830 to report for the second day of the trip sequence, which consisted of five

scheduled flights starting about 0930. Each flight was expected to last about 1 hour. The

pilot completed three of the scheduled flights before the accident flight occurred.

1.5.1.1 Flight Check History

Between April 1983 and February 1998, the pilot received the following notices of

disapproval from the FAA:

• In April and May 1983, the pilot received notices of disapproval because he

failed the entire flight test portion of the flight checks

18

he was receiving for

his private pilot certificate. On June 22, 1983, the pilot was rechecked

successfully, and he received his private pilot certificate.

• On October 30, 1985, the pilot received a notice of disapproval because he

failed the “holding” and the “recovery from an unusual attitudes” portions of

the flight check he was receiving for his instrument rating. On November 8,

1985, the pilot was rechecked successfully, and he received his instrument

rating.

• In December 1987 and February 1988, the pilot received notices of disapproval

because he failed the entire flight test portion of the flight checks he was

receiving for his CFI certificate. On March 17, 1988, the pilot was rechecked

successfully, and he received his CFI certificate.

17

A description of this accident, MIA00LA109, can be found on the Safety Board’s Web site at

<http://www.ntsb.gov>.

18

If a pilot receives a notice of disapproval for a flight check, the pilot can be required to be rechecked

on the complete flight check or on designated portions of the flight check.

Factual Information 7 Aircraft Accident Report

• In July 1988 and May 1989, the pilot received notices of disapproval because

he failed the entire flight test portion of the flight checks he was receiving for

his CFI instrument rating. In August 1989, he received another notice of

disapproval because he failed the “holding” portion of the flight check and did

not complete three other portions of the check. On December 8, 1989, the pilot

was rechecked successfully, and he received his CFI instrument rating.

• In February 1998, the pilot received a notice of disapproval because he failed

the “nondirectional beacon approach” portion of the flight check he was

receiving for his ATP certificate. On March 7, 1998, the pilot was rechecked

successfully, and he received his ATP certificate.

1.5.2 The Director of Maintenance

Air Sunshine’s Director of Maintenance was hired by the company in March 1997

as a mechanic; seven months later, he was promoted to Director of Maintenance.

On October 28, 1989, the Director of Maintenance applied for his airframe and

powerplant (A&P) certificate based on work experience

19

he obtained while working as an

assistant mechanic from March 1985 to the date of the application. On October 24, 1990, the

director took the oral and practical examinations required by 14 CFR 65.79.

20

He passed all

of the oral examinations; however, he failed the following portions of the practical exam:

Section I, General – Airframe and Powerplant, subsections (A) weight and balance and

(B) completion of FAA Form 337; and Section IV, Powerplant Theory and Maintenance,

subsection (A) troubleshooting of turbine engines. The director received additional training

in these areas and retook the practical exam on October 30, 1990, at which time he received

his A&P certificate. A search of FAA records found no evidence of enforcement actions.

The Director of Maintenance reported that, from March 1985 to August 1990, he

worked as an assistant mechanic on Cessna 402 airplanes at Airways International, a

14 CFR Part 135 on-demand charter operator in Miami. From January 1988 to March 1989,

he also worked part-time as an assistant mechanic on McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and

Lockheed L-1011 airplanes at Eastern Airlines in Miami. From mid-1990 to mid-1996, he

worked as a mechanic at Airways International. From August 1996 to March 1997, he

worked as a mechanic on Cessna 402, 210, and 206; Piper Cherokee; Britten-Norman

Islander; and Beechcraft 55 and 58 airplanes at Flightline of America, Pembroke Pines,

Florida.

19

According to 14 CFR 65.77, “Experience Requirements,” “each applicant [for a mechanic certificate or

rating]…must present either an appropriate graduation certificate or certificate of completion from a certificated

aviation maintenance technician school or documentary evidence of…at least 30 months of practical experience

concurrently performing the duties appropriate to both the airframe and powerplant ratings.”

20

According to 14 CFR 65.79, “Skill Requirements,” “each applicant [for a mechanic certificate or

rating]…must pass an oral and a practical test on the rating he seeks. The tests cover the applicant’s basic skill in

performing practical projects on the subjects covered by the written test for that rating. An applicant for a

powerplant rating must show his ability to make satisfactory minor repairs to, and minor alterations of,

propellers.”

Factual Information 8 Aircraft Accident Report

1.5.3 The Assistant Mechanic

Air Sunshine’s assistant mechanic was hired by the company on June 6, 2000, to

work in San Juan, Puerto Rico. In March 2003, he transferred to the company’s facility at

FLL. The assistant mechanic did not have an A&P certificate.

On March 31, 2003, the Director of Maintenance signed off a Certificate of

Training for the assistant mechanic, indicating that he had completed 30 hours of basic

indoctrination training. On April 30, 2003, the director signed off a Certificate of Training

for the assistant mechanic, indicating that he had completed 60 hours of aircraft subjects

training. On June 30, 2003, the director signed off a Certificate of Training for the

assistant mechanic, indicating that he had completed 200 hours of on-the-job training for

the “entire aircraft, airframe, engine, propeller, accessories, etc.”

1.6 Airplane Information

The accident airplane, serial number 402C0413, was manufactured by Cessna

Aircraft Company on November 24, 1980. The airplane was operated by several airlines

21

before being sold to Tropical International Airlines, Inc.,

22

on August 29, 1997. From

mid-1997 to late 2000, the airplane was kept at the company’s maintenance facility at FLL.

Air Sunshine’s President stated that, during this time, extensive maintenance was being

performed on the airplane, including left and right engines and propellers replacement, sheet

metal repair, corrosion treatment, and landing gear repair, to make it airworthy.

Tropical International Airlines leased the airplane to Air Sunshine on November 1,

2000.

23

The airplane was inspected in accordance with Air Sunshine’s FAA Approved

Aircraft Inspection Program (AAIP) on November 20, 2000, and found to be airworthy.

24

The airplane was added to the company’s operations specifications on December 6, 2000.

The airplane was configured with a pilot seat (left side), a copilot seat (right side),

and eight passenger seats. (See figure 1.) The airplane was equipped with a window

escape hatch adjacent to the pilot seat (1A); an emergency escape hatch adjacent to seats 2B

and 3B; and a two-section outward opening airstair door (main cabin door) adjacent to

seats 4A and 5A, the lower portion of which was equipped with stairs. The pilot and

copilot seats were equipped with lapbelts and single-strap shoulder harnesses, and the

passenger seats were equipped with lapbelts.

21

On March 1, 1992, the airplane was involved in a nose landing gear collapse while being operated by

Airways International. For more information about this accident, MIA92IA090, see the Safety Board’s Web

site at <http://www.ntsb.gov>.

22

Tropical International Airlines was owned and operated by the same people who own and operate Air

Sunshine.

23

The lease agreement stated that Air Sunshine would be responsible for all expenses, including

maintenance.

24

For more information about Air Sunshine’s AAIP, see section 1.6.1.1

Factual Information 9 Aircraft Accident Report

According to the load manifest form for the accident flight, the airplane’s takeoff

weight was about 6,644 pounds, including 890 pounds of passenger weight,

25

350 pounds

of baggage weight, and 800 pounds of fuel weight. The airplane’s takeoff center of gravity

(CG) was 154.61 inches aft of the reference datum. After the airplane was retrieved from

the water,

26

the baggage was removed from the airplane, dried, and weighed. The baggage

weighed 440.85 pounds, 90 pounds more than the amount that was entered on the load

manifest form. After applying the additional 90 pounds, the weight and CG were still

within acceptable limits.

27

1.6.1 Engines and Propellers

The airplane was equipped with two Teledyne Continental Motors (TCM)

TSIO-520-VB reciprocating engines. These engines are turbo-charged and fuel-injected

with six horizontally opposed air-cooled cylinders. The engines are rated for 325 horsepower

at a power setting of 2,700 rpm with 39 inches Hg manifold pressure up to an altitude of

12,000 feet.

Figure 1. Interior configuration of the accident airplane.

25

Actual passenger weights were used to calculate the total passenger weight.

26

The airplane was retrieved from the water on August 3, 2003. The retrieval was delayed because of

choppy waters.

27

According to the Cessna 402C Pilot Operating Handbook, the airplane’s maximum gross takeoff

weight is 7,210 pounds, and the maximum gross landing weight is 6,850 pounds. The maximum forward CG

for flight 527 was 151.2 inches aft of the reference datum, and the maximum aft CG for the flight was

160.7 inches.

Factual Information 10 Aircraft Accident Report

The engine cylinders incorporate an overhead inclined valve design. The cylinders

have updraft intake inlets and downdraft exhaust outlets mounted to the underside of the

cylinder heads. Each of the six cylinders is attached to the engine case by a series of

threaded studs, through bolts, and nuts. Six 7/16-inch, 20 threads-per-inch studs are

threaded into the case half for exclusive use at each cylinder location and are held down

by 6-point nuts. Additional studs are positioned between the cylinders and are shared by

adjacent cylinders. Two 1/2-inch through bolts, which are located at the engine crankshaft

main bearing positions, are either shared by opposed cylinders or the opposite crankcase

half and are held down by 12-point nuts.

The right engine, serial number 529092, and the left engine, serial

number 811069-R, were manufactured by TCM on February 1, 1991, and January 1, 1997,

respectively. Airmark Overhaul, Inc., in Fort Lauderdale

28

overhauled the right and left

engines on December 14 and December 21, 1999, respectively.

29

At the time of overhaul,

the right and left engines had times since new of 3,582.6 flight hours and 2,400.0 flight

hours, respectively. The right and left engines were installed on the accident airplane on

October 10 and 7, 2000, respectively. The last routine engine maintenance, which included

changing the oil, inspecting the oil filter, looking for leaks, and performing a ground

run-up, was conducted on July 8, 2003, and the time since overhaul for both engines at

that time was 2,246.5 flight hours. At the time of the accident, both engines had a time

since overhaul of 2,270.6 flight hours.

30

The airplane was equipped with two McCauley Propeller Systems 3AF32C505-C

three-bladed, dual-acting, constant-speed propellers. The blades are counterweighted to

help move them toward higher blade angles (that is, toward feather) during operation.

A feather spring inside the propeller moves the blades to the high-pitch (feather) stops.

A centrifugal start-lock system, which uses spring-loaded pins that engage the piston as

the propeller speed drops below approximately 600 rpm, prevents the blades from

traveling all the way to feather during normal engine shutdowns, which reduces the load

on the engine during subsequent engine starts.

1.6.1.1 Air Sunshine’s Approved Aircraft Inspection Program

As a 14 CFR Part 135 operator, Air Sunshine had the option to operate either under

the manufacturers’ maintenance inspection programs or to develop and receive FAA

approval for its own maintenance inspection program. From 1982 to 1992, Air Sunshine

operated under the manufacturers’ (Cessna, TCM, and McCauley Propeller) maintenance

inspection programs.

In early 1992, under the oversight of the Fort Lauderdale Flight Standards District

Office (FSDO), Air Sunshine developed and received approval for its own inspection

28

Airmark Overhaul is an FAA-approved maintenance vendor for Air Sunshine.

29

Maintenance records were not available from the dates of manufacture of the right and left engines to

the dates of the overhauls.

30

For information about TCM’s recommended overhaul limit and Air Sunshine’s overhaul interval, see

section 1.6.1.3.

Factual Information 11 Aircraft Accident Report

program. The company’s initial AAIP was a 3-phase, 60-hour inspection program.

A different phase was performed every 60 hours of operation along with a routine

servicing check, which included an engine oil change, a ground run-up, and a visual

inspection of the airframe. Phases 1 through 3 comprised one full cycle, and an airplane

had to complete one full cycle (that is, the entire aircraft had to have been inspected) every

180 hours of operation.

On November 4, 2002, Air Sunshine submitted revision No. 10, which proposed to

change the company’s AAIP to a 6-phase, 60-hour inspection program, to the FAA for

approval. On January 9, 2003, the FAA approved the change,

31

and the 6-phase, 60-hour

inspection program was in effect at the time of the accident. Each of the six phase

inspections focused on one major airplane section. Phase 1 covered the powerplants,

including a focused engine inspection and a differential compression check of the engine

cylinders; phase 2 covered the wings; phase 3 covered the cabin; phase 4 covered the

landing gear; phase 5 covered the fuselage; and phase 6 covered the empennage. Phases 1

through 6 comprised one full cycle, and an airplane had to complete one full cycle every

360 hours of operation. The last phase 1 inspection was performed at FLL from June 12

to 14, 2003. During this inspection, each engine was determined to have a time since

overhaul of 2,187 flight hours.

1.6.1.2 Differential Compression Checks

TCM Service Bulletin (SB) 03-3 states that differential compression checks are

conducted to identify leaks in the engine cylinders and the sources of any leaks that were

found and that leaks can be caused by abnormal or excessive wear inside the engine

cylinders or their components, problems with the valves or valve seats, and cracks in the

cylinders. The SB also states that compression checks should be conducted “at each

100 hour interval, annual inspection or when cylinder problems are suspected.”

32

According to SB 03-3, before conducting the differential compression check, the

acceptable pressure leakage limit for the equipment being used and the atmospheric

conditions at the time that the check is conducted need to be established. SB 03-3 contains the

following instructions on how to perform differential compression checks on all of its engines:

• remove the most accessible spark plug from each of the six cylinders on each

engine;

• turn the engine crankshaft by hand in the direction of rotation until the piston is

coming up on top dead center at the end of the compression stroke;

31

In early 1998, Air Sunshine requested that its operating certificate be transferred from the FAA’s Fort

Lauderdale FSDO to its San Juan FSDO. The FAA granted the request, and the transfer took place on June 2,

1998. The company’s operating certificate was under the jurisdiction of the San Juan FSDO when the

company applied and was approved to change its AAIP. For more information about FAA oversight of Air

Sunshine, see section 1.17.2.

32

For information about the postaccident change to the differential compression check interval and

other changes to Air Sunshine’s AAIP, see section 1.17.2.5.

Factual Information 12 Aircraft Accident Report

• install a cylinder adapter in the spark plug hole and connect a differential

pressure tester to the cylinder adapter and slowly open the cylinder pressure

valve and pressurize the cylinder to 20 pounds per square inch (psi);

• continue to rotate the engine in the direction of rotation, against the pressure,

until the piston reaches top dead center (that is, with the piston at the end of the

compression stroke and the beginning of the power stroke);

• open the cylinder pressure valve completely;

• move the propeller slightly back and forth with a rocking motion while

directing regulated pressure of 80 psi into the cylinder and adjust regulator as

necessary to maintain a pressure gauge reading of 80 psi; and

• record the pressure indication on the cylinder pressure gauge.

The difference between the pressure directed into the cylinder (80 psi) and the

cylinder pressure shown on the regulator pressure gauge is the amount of leakage through

the cylinder. Any cylinder pressure level greater than that established as the acceptable

pressure leakage limit indicates an acceptable operating condition for a reciprocating

engine. The SB recommends that, if the cylinder pressure levels are less than the

acceptable pressure leakage limit, cylinder borescope inspections should be conducted.

1.6.1.2.1 June 12 to 14, 2003, Differential Compression Checks

As noted previously, the last differential compression checks performed on the

accident airplane’s engines occurred from June 12 to 14, 2003, as part of the airplane’s last

phase 1 inspection. According to the Director of Maintenance, he performed the checks on

the left engine while the assistant mechanic watched and then recorded the readings in the

inspection record. The cylinder differential compression check form

33

in Air Sunshine’s

Maintenance Manual contains the following: “CAUTION - It is recommended that

someone hold the propeller during this check to prevent possible rotation.” (See figure 2.)

The Director of Maintenance stated that, after completing the checks on the left

engine, he asked the assistant mechanic if he felt capable of performing the checks on the

right engine without supervision. The director stated that the assistant replied that he could

perform the checks; as a result, the director left the assistant to perform the checks by

himself without supervision. According to the director, he asked the assistant mechanic to

record the compression check readings for the right engine on a sheet of paper so that he

could review them before making the entries in the cylinder differential compression check

form in the inspection records; however, the assistant mechanic recorded the readings

directly in the inspection record. Figure 2 also shows the compression check readings (in

psi) recorded in the inspection record by the assistant mechanic for both engines.

Accounting for the check equipment used at the time that the checks were performed, the

Safety Board determined that the acceptable pressure leakage limit was 54 psi.

33

The cylinder differential compression check form is part of the company’s AAIP phase 1 inspection

package.

Factual Information 13 Aircraft Accident Report

Note: According to the assistant mechanic and the Director of Maintenance, the number recorded for right engine cylinder

No. 3 was “55.” (Safety Board investigators who reviewed the document noted that the number could be either “55” or “25.”)

The assistant mechanic’s signature and A&P certificate number have been redacted.

Figure 2. Cylinder differential compression check form.

Factual Information 14 Aircraft Accident Report

During postaccident interviews, the assistant mechanic stated that he had never

performed a differential compression check before conducting the checks on the accident

airplane’s right engine. The assistant stated that his normal duties included changing oil,

tires, cables, and spark plugs and cleaning the airplane. When a Safety Board investigator

asked the assistant how to perform the compression check, he stated only that the spark

plugs had to be removed from the cylinders and that the piston had to be at top dead center

on its compression stroke.

The Director of Maintenance stated that, as he was reviewing and signing off on

the day’s maintenance work, he noticed that two of the readings obtained from the

compression checks of the right engine (0 psi for the No. 2 cylinder and 20 psi for the

No. 4 cylinder)

34

were “highly questionable.” The director stated that he asked the

assistant mechanic if he had been careful to get the piston at top dead center on its

compression stroke on each cylinder when he performed the check. The director indicated

that, although the assistant stated that he had been careful to get the piston into its required

position, he appeared uncertain when asked specifically about the two questionable

cylinder readings. The director told the assistant mechanic that the compression checks on

the right engine cylinders would have to be repeated.

According to the Director of Maintenance, after he repeated the checks on the right

engine, all of the cylinder’s compression readings were in the 70-psi range, including the

two cylinders with low readings from the first compression checks. The director stated

that, when he did the rechecks, he was careful to get the piston at top dead center on its

compression stroke and hold the propeller while adding the pressure. He added that, if the

compression level readings had remained low, he would have grounded the airplane. The

director stated that he had the assistant mechanic observe the checks and record the

readings on a sheet of paper. The assistant mechanic stated that he gave the sheet of paper

to the director but that he did not see what the director did with the paper. The director

stated that he recorded the corrected readings on a new cylinder differential compression

check form; however, company personnel did not locate the corrected form. The director

stated that he did not conduct cylinder borescope inspections on cylinder Nos. 2 and 4

because the repeated compression checks yielded readings that were within acceptable

limits.

The Director of Maintenance stated that the company had removed and replaced

an engine cylinder assembly about five or six times in the last 3 years. The director stated

that, before applying torque to the cylinder studs, maintenance personnel coated the studs

with an aluminum-copper-graphite, lithium-based antiseize compound manufactured by

Permatex. TCM SB 96-7B specifies that clean 50-weight aviation-grade engine oil should

be applied to the studs and through bolts before applying torque. Permatex does not

recommend using antiseize compound in high-vibratory environments because such use

could contribute to the loss of torque.

34

The Director of Maintenance stated that he would consider any reading below 58 psi to be too low

and that low readings would require that the cylinder be rechecked. The director did not mention that the

reading recorded for cylinder No. 3 was too low, even though he stated that it was “55.”

Factual Information 15 Aircraft Accident Report

1.6.1.3 Time Between Overhauls

TCM Service Information Letter 98-9A recommends that TSIO-520-VB engines

have a time between overhaul (TBO) of 1,600 hours. Air Sunshine began operating its

airplanes equipped with TSIO-520-VB engines in accordance with this recommendation.

After Air Sunshine’s inspection program received FAA approval in early 1992,

35

the

company applied to the Fort Lauderdale FSDO for a 200-hour extension of its TBO per

the procedures outlined in FAA Order 8300.10, Airworthiness Inspector’s Handbook.

36

The FAA principal maintenance inspector (PMI) for Air Sunshine granted its request and

allowed the company to increase its TBO by 200 hours. From late 1992 to late 1995, Air

Sunshine applied for four additional TBO extensions (of 200 hours, 200 hours, 100 hours,

and 100 hours) for a total TBO extension of 800 hours. The FAA granted approval for all

of the requested extensions, which resulted in a TBO of 2,400 hours.

According to FAA Order 8300.10, approval of TBO extensions is granted based on

“satisfactory service experience and/or a teardown examination of at least one exhibit

engine.” Neither the FAA nor Air Sunshine had retained the paperwork that related to the

five requests for, and approvals of, the extensions of the company’s TBO for longer than

the 2 years required by the FAA. However, Air Sunshine provided the Safety Board with

four teardown reports prepared by Airmark Overhaul (which were submitted as support

for the first four TBO extension requests) and one report prepared by TCM (which was

submitted as support for the last request). These reports were dated July 16, 1992;

November 17, 1992; March 20, 1994; January 20, 1995; and October 9, 1995. All of the

teardowns conducted by Airmark and TCM were of TCM-rebuilt engines.

After Air Sunshine received approval for the last 100-hour TBO extension, the

company petitioned the Fort Lauderdale FSDO to change the company’s operations

specifications to reflect the 2,400-hour TBO, and the Fort Lauderdale FSDO granted the

request under the condition that the company’s airplane engines be rebuilt by TCM. In late

August/early September 1999, after Air Sunshine transferred its operations certificate to

the San Juan FSDO, the company petitioned the San Juan FSDO to remove from the

company’s operations specifications the requirement that TCM rebuilt engines must be

used.

In a letter dated September 9, 1999, the FAA PMI for Air Sunshine stated that he

would grant the company’s request provided it (1) monitored the performance of newly

overhauled engines and reported any abnormal conditions to the San Juan FSDO,

37

(2) used

35

Air Sunshine was required to have its own AAIP to receive FAA approval for TBO extensions.

36

FAA Order 8300.10 indicates that TBO extensions for reciprocating engines can be granted in

increments of up to 200 hours.

37

A review of Air Sunshine and FAA records revealed that the company made no reports to the FAA

between the date of this letter and the date of the accident in which the company reported any abnormal

conditions of its overhauled engines.

Factual Information 16 Aircraft Accident Report

the approved overhaul facilities listed in its Maintenance Manual vendor list,

38

and

(3) established standards for parts to be used during the overhaul process. The PMI added

that, if the engines did not perform satisfactorily, the company’s operations specifications

would be amended back to the original TBO of 1,600 flight hours.

39

1.7 Meteorological Information

The closest airport to the location of the airplane wreckage was Grand Bahamas

International Airport (MYGF), Freeport, Bahamas, which was about 63.9 nautical miles

from where the airplane was located. MYGF does not have an automated weather system.

Weather observations are made by an on-site weather observer and are recorded in

coordinated universal time. Eastern daylight time is 4 hours behind coordinated universal

time.

The 1900 meteorological aerodrome report (METAR) (1500 local time, which was

about 30 minutes before the ditching) indicated that winds were 160° at 8 knots, visibility

was 10 nautical miles, clouds were broken at 2,000 feet, the temperature was 88.5° F, the

dew point was 74.1° F, and the altimeter setting was 30.09 inches of Hg.

The 2000 METAR (1600 local time, which was about 30 minutes after the

ditching) indicated that winds were 140° at 10 knots, visibility was 10 nautical miles, a

few clouds were at 1,500 feet and were scattered at 2,000 feet, the temperature was 88.5° F,

the dew point was 74.1° F, and the altimeter setting was 30.08 inches of Hg.

1.8 Aids to Navigation

The distance measuring equipment on the MYAT VOR

40

had been inoperative for

several years.

1.9 Communications

No communication problems were reported.

1.10 Airport Information

MYAT was the destination airport for flight 527. The airplane was ditched about

7.35 nautical miles west-northwest of the airport.

38

After its operations specifications were amended, Air Sunshine started using Airmark Overhaul, a

company on the FAA-approved vendor list, to overhaul its engines.

39

For information about postaccident changes to Air Sunshine’s operations specifications, see

section 1.17.2.5.

40

VOR stands for very high frequency omnidirectional range.

Factual Information 17 Aircraft Accident Report

1.11 Flight Recorders

The accident airplane was not equipped with either a CVR or an FDR and was not

required to be so equipped.

1.12 Wreckage and Impact Information

1.12.1 General

The airplane was submerged in water for about 3 weeks after the accident.

Underwater photographs taken before the airplane was recovered from the water showed

that the window escape hatch adjacent to the pilot seat (1A) was open. The emergency

escape hatch adjacent to seats 2B and 3B was found closed. The top and bottom portions

of the main cabin door adjacent to seats 4A and 5A were found open.

Impact damage was noted on the lower fuselage skin from the wing main spar

forward, and damage was noted on the nose cone. The landing gear was found retracted.

All of the airplane’s major components,

41

except for the left aileron and the

outboard section of the right elevator and balance weight, were recovered attached to the

airplane. The separated sections were not recovered. The rudder trim tab actuator was

found positioned between 5° and 10° trailing edge tab right; the elevator trim tab actuator

was found positioned at 15° trailing edge tab down. The left flap was found extended

about 15°, and the cowl flap was nearly closed. The right flap was found extended about 15°,

and the cowl flap was open. An oil sheen was noted on the exterior surface of the right

engine upper cowling, from the louvers aft to the trailing edge of the wing; on the interior

surface of the upper cowling; and on the upper and lower exterior surfaces of the

horizontal stabilizer.

The left fuel selector valve handle in the cockpit was found positioned to the left

main fuel tank; the right fuel selector valve handle was missing; therefore, its position

could not be determined. The emergency crossfeed/shutoff valve handle was found

positioned to the crossfeed position. The left and right auxiliary fuel pump switches were

found in the off position. The left and right cowl flap controls were found out (closed) and

in (open), respectively. Both the flap selector and flap position indicator were found at

about 15° flaps extended,

42

and the landing gear selector handle was found in the retracted

position. The elevator trim indicator was found positioned to full nose up. The aileron trim

indicator was found positioned slight left wing down. The rudder trim indicator was found

positioned nose left.

41

A major component is necessary for an airplane to sustain flight.

42

During postaccident interviews, the pilot stated that he did not extend the flaps during the flight. The

pilot stated that he would normally extend the flaps when he was about 3 miles from an airport. When he

was asked how the flaps became extended to 15°, the pilot replied that after the ditching, some of the

passengers crawled over him and that one of them might have hit the switch that extended the flaps. He

stated that the flaps were extended electrically and that he had left the power on after the ditching.

Factual Information 18 Aircraft Accident Report

All seats were found attached to the floor and were undamaged. All lapbelts were

present and were found to operate normally. The seatback stowage pockets for seats 2A

and 2B did not contain safety briefing cards;

43

all of the other stowage pockets contained

briefing cards.

Six packaged PFDs were found in the airplane. One PFD was found forward of the

pilot seat, and one PFD was found forward of the copilot seat. The remaining four PFDs

were found in their stowage areas (under seats 2A, 2B, 3A, and 5A). The PFDs were

brought to the Safety Board’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., and were examined on

August 28, 2003. The sealed plastic pouches were opened, and the PFDs were inflated by

pulling the inflation rings. All of the PFDs were undamaged and were found to operate

normally. Inspection records found inside the plastic pouches containing the PFDs

indicated that they had been inspected within the past 5 years, in accordance with Federal

regulations.

1.12.2 Engines and Propellers

The left engine was attached to the airframe, and the propeller was attached to the

engine. The outboard lower engine cowling had separated and was not located. The left

engine was removed and examined, under Safety Board supervision, at TCM’s facility. All

six cylinders and their valves were intact. No evidence of preexisting damage was found.

The left propeller was removed and examined, under Safety Board supervision, at

McCauley Propellers’ facility. The left propeller hub was intact and undamaged, and all

three blades were installed in the hub. Examination of the left propeller revealed no

evidence of preimpact damage. The feather-stop mechanism was attached and

undamaged, and the start-lock mechanism

44

was intact and undamaged.

The right engine was attached to the airframe in its normal position, and the

propeller was attached to the engine. Damage was noted on the leading edge skin from the

engine outboard to the wing tip; the leading edge skin from the engine nacelle inboard of

the wing root was crushed up and aft. The lower inboard engine cowling was separated

and was not recovered; the lower outboard engine cowling was in place.

The right engine No. 2 (inboard aft) cylinder was found separated from the engine

crankcase, exposing a portion of the crankshaft, and held onto the engine by the exhaust

pipe tubing and by an electrical cable that was secured to the cylinder assembly by an adel

clamp. The two magnetos were found protruding through the upper outboard engine

cowling but remained attached to the engine by ignition leads. (See figure 3.) Two 6-point

flanged nuts, one 12-point flanged nut with a fractured threaded piece, and a nonfractured

connecting rod were recovered from the engine compartment area. Piston ring pieces were

found in the partially separated No. 2 cylinder assembly.

43

The stowage pockets on these seatbacks held the briefing cards for use by the passengers in seats 3A

and 3B. For more information about the airplane’s interior configuration, see section 1.6.

44

As noted previously, the start-lock mechanism is a system designed to prevent the propeller from

traveling all the way to feather during normal engine shutdowns.

Factual Information 19 Aircraft Accident Report

The right engine was removed and examined, under Safety Board supervision, at

TCM’s facility. After engine disassembly at TCM, some of the right engine components

were brought to the Safety Board’s Materials Laboratory in Washington, D.C., for further

examination. For additional information about the metallurgical inspections of the right

engine components, see section 1.16.3.

The right propeller was removed and examined, under Safety Board supervision,

at McCauley Propeller’s facility. The right propeller hub was intact and undamaged, and

all three blades were intact and installed in the hub and appeared to be in the feathered

position. The blade angles were measured as follows: blade No. 1 was 82.2°, blade No. 2

was 82.4°, and blade No. 3 was 82.3°. The feather angle for this propeller is 82.2°

(+/-0.3°). All of the blade counterweights were present and in place. The propeller piston

was undamaged, and the centrifugal weights and springs were in place. The piston rod and

feathering spring were intact, in place, and undamaged. The feather-stop and start-lock

mechanisms were intact and undamaged.

Figure 3. Exterior of the upper outboard engine cowling.

Factual Information 20 Aircraft Accident Report

1.13 Medical and Pathological Information

Fluid specimens obtained from the pilot were sent to the Royal Bahamas Police

Force’s Forensic Science Laboratory for toxicological analysis. The fluid specimens tested

negative for alcohol and drugs.

45

According to the Rand Memorial Hospital (Freeport, Grand Bahamas) autopsy

report, the cause of death for the deceased 4-year-old child was “drowning secondary to

plane crash.” According to the Princess Margaret Hospital (Freeport, Grand Bahamas)

pathology report, the deceased adult passenger had injuries “consistent with the history of

plane crash accident.” Further, the report stated that the deceased adult passenger had a

cerebral contusion and rib fractures. The report also stated that a “section of both lungs

showed edema and congestion.”

1.14 Fire

No evidence of an in-flight fire was found, and the accident did not result in a

postcrash fire.

1.15 Survival Aspects

1.15.1 General

The pilot reported that he was not wearing his shoulder harness when the airplane

contacted the water and that he hit his head on the instrument panel during the ditching.

46

During postaccident interviews, one passenger stated that the pilot “did not appear to have

much clarity and was not particularly coherent” after the ditching. Another passenger

stated that he “took charge of the situation because the pilot was incoherent in the water.”

The passenger also stated that the pilot “did not look like he could swim” and that he had

to give the pilot his PFD.

The passenger in the copilot seat reported a bump on his head and a cut on his leg.

The passenger stated that he was not wearing his shoulder harness during the ditching

because the pilot had not informed him before the flight departed that his seat was so

equipped. The passengers in seats 2A and 2B reported bruises on their hips from the

lapbelts. The passenger in seat 3B reported a contusion on her forehead.

After the airplane contacted the water, the pilot opened the pilot-side window

hatch. The pilot, four adult passengers (from the copilot seat and seats 2A, 2B, and 3B),

45

The drugs tested in the postaccident analysis included benzoylecgonine, barbiturates,

benzodiazapines, and opiates.

46

Title 14 CFR 91.105(b) requires that required flight crewmembers of a U.S.-registered civil aircraft

keep their shoulder harnesses fastened while at their assigned duty stations during takeoff and landing.

Factual Information 21 Aircraft Accident Report

and one child (who had been sitting on the passenger in seat 3B’s lap) evacuated the

airplane through the pilot-side window escape hatch. One adult and three children (from

seats 4A, 4B, 5A, and 5B) evacuated the airplane through the main cabin door.

1.15.2 Emergency Briefings

Air Sunshine’s FAA-approved General Operations Manual, Section 4, “Emergency

Procedures,” contains the following guidance to pilots on briefing passengers before a

ditching:

• review the emergency ditching evacuation procedures with the passengers;

• instruct passengers to don life vests at that time, without inflating them in the

airplane;

• review the operation of the inflation ring and the manual/oral blow-up tubes;

and

• instruct passengers to inflate their life vests once they are outside of the aircraft.

As noted previously, passengers reported that the pilot did not tell them to retrieve

and don their PFDs before the airplane contacted the water. They stated that the only time

he addressed the passengers after the right engine failed and before the airplane contacted

the water was to tell them to “calm down.”

As the result of a postaccident focused inspection of Air Sunshine (conducted from

July 22 to August 29, 2003), the FAA instructed the company to amend its emergency

ditching procedures.

47

The amended procedures contain the following guidance to pilots

on briefing passengers before a ditching:

• instruct all passengers to don life vests as soon as any emergency occurs during

overwater operation;

• instruct passengers to familiarize themselves with emergency evacuation

procedures, including special evacuation procedures for those passengers who