RACE

OF

PHYSICIAN

AND

SATISFACTION

WITH

CARE

AMONG

AFRICAN-

AMERICAN

PATIENTS

Thomas

A.

LaVeist,

PhD,

and

Tamyra

Carroll

Baltimore,

Maryland

The

purpose

of

this

study

is

to

examine

predictors

of

physician-patient

race

concordance

and

the

effect

of

race

concordance

on

patients'

satisfaction

with

their

primary

physicians

among

African

American

patients.

The

specific

research

question

is,

do

African

American

patients

express

greater

satisfaction

with

their

care

when

they

have

an

African

American

physician?

Using

the

Commonwealth

Fund,

Minority

Health

Survey,

we

conduct

multivariate

analysis

of

African

American

respondents

who

have

a

usual

source

of

care

(n

=

745).

More

than

21%

of

African

American

patients

reported

having

an

African

American

physician.

Patient

income

and

having

a

choice

in

the

selection

of

the

physician

were

significant

predictors

of

race

concordance.

And,

patients

who

were

race

concordant

reported

higher

levels

of

satisfaction

with

care

com-

pared

with

African

American

patients

thatwere

not

race

concordant.

(J

NatlMedAssoc.

2002;

94:937-943.)

INTRODUCTION

Race

relations

have

been

among

the

most

vexing

problems

facing

American

culture,

and

healthcare

has

not

been

immune

to

this.

Through

most

of

the

20th

century,

healthcare

facilities

were

racially

segregated,

with

African

Americans

generally

receiving

suboptimal

care.

In

addition,

African

American

physicians

were

typically

barred

from

practicing

medicine

on

white

patients.1

2

While

many

of

these

condi-

tions

have

abated,

vestiges

of

this

history

re-

main.

There

is

substantial

contemporary

evi-

©

2002.

From

the

Center

for

Health

Disparities

Solutions,

Bloomberg

School

of

Public

Health,

Johns

Hopkins

University.

Address

reprint

requests

to

Dr.

Thomas

LaVeist,

Johns

Hopkins

University,

Bloomberg

School

of

Public

Health,

624

North

Broadway,

Baltimore,

MD

21205;

phone

(410)

955-3774;

fax

(410)

614-8964;

or

direct

e-mail

to

dence

of

race

disparities

in

access,

utilization

and

quality

of

care.3"14'15

Among

the

most

commonly

proposed

solu-

tions

to

race

disparities

in

quality

of

care,

is

the

recommendation

to

increase

the

number

of

African

American

healthcare

providers.

This

suggestion

supposes

that

increasing

the

num-

ber

of

providers

will

increase

the

likelihood

that

African

American

patients

will

have

an

African

American

provider.

In

turn,

physician-

patient

race

concordance

is

expected

to

lead

to

better

quality

care

and

greater

patient

satisfac-

tion.28

Medical

schools

have

responded

to

this

proposition

by

increasing

the

production

of

minority

physicians.4'5

Yet,

although

quite

pop-

ular,

the

race

concordance

hypothesis

has

re-

ceived

only

limited

scrutiny.

In

this

paper,

we

address

the

question,

do

African

American

pa-

tients

express

greater

satisfaction

with

their

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

94,

NO.

11,

NOVEMBER

2002

937

DOCTOR

RACE

AND

PATIENT

SATISFACTION

care

when

they

have

an

African

American

phy-

sician?

METHODS

Data

for

this

analysis

came

from

the

1994

Commonwealth

Fund

Minority

Health

Survey

(MHS).

The

MHS

is

a

sample

within

the

con-

tiguous

United

States

of

adults

18

years

of

age

and

older

residing

in

households

with

tele-

phones.6

Interviews

were

conducted

via

tele-

phone

using

random

digit

dialing.

African

Americans

were

over-sampled

in

the

MHS,

re-

sulting

in

a

total

sample

of

1048

African

Amer-

ican

respondents.

The

present

analysis

exam-

ines

the

subsample

of

745 African

American

respondents

who

indicated

that

they

had

a

usual

source

of

care.

Dependent

Variables

The

first

set

of

analyses

examined

predictors

of

race

concordance,

and

the

second

set

exam-

ined

patient

satisfaction.

Race

concordance

was

specified

as

a

binary

variable

indicating

that

the

respondent's

race

is

concordant

with

the

race

of

the

physician.

Patient

satisfaction

is

assessed

by

a

five-item

scale.

Respondents

were

asked

how

good

their

doctor

is

at:

(1)

providing

good

healthcare

overall;

(2)

treating

them

with

dig-

nity;

(3)

making

sure

the

patient

understands

what

he/she

has

been

told;

(4)

listening

to

health

problems;

(5)

being

assessable

by

phone

or

in

person.

The

responses

were

on

a

scale

of

1

to

4,

with

1

being

excellent

and

4

being

poor.

In

the

regression

analysis,

responses

to

the

five

items

were

summarized

to

form

an

index

rang-

ing

from

5

to

20.

This

index

had

a

Chronbach's

Alpha

of

0.81.

Independent

Variables

In

analysis

predicting

race

concordance,

physician

choice

was

the

primary

independent

variable.

Physician

choice

was

measured

by

the

question,

"How

much

choice

you

do

have

in

where

you

go

for

medical

care?"

Respondents

indicating

that

they

have

a

"great

deal"

or

"some"

were

coded

as

having

a

choice,

and

responses

of

"very

little"~

or

"no

choice"

were

coded

as

no

choice.

In

analysis

of

patient

satis-

faction,

physician-patient

race

concordance

was

the

primary

independent

variable.

Covariates

The

covariates

were

sex,

age,

income,

educa-

tion,

and

health

insurance.

Sex

was

specified

as

a

binary

variable

indicating

male.

Age

was

spec-

ified

as

a

set

of

binary

variables

indicating

age:

18-30,

31-40,

41-50,

51-65,

and

66-94.

An-

nual

income

was

specified

as

a

continuous

vari-

able.

Education

was

specified

as

a

set

of

binary

variables

indicating

less

than

high

school

grad-

uate,

some

college,

college

graduate,

and

more

than

college

graduate.

Health

insurance

was

specified

as

a

set

of

binary

variables

indicating

private

insurance,

Medicare,

Medicaid,

and

un-

insured.

RESULTS

Table

1

presents

distributions

of

the

vari-

ables

included

in

the

analysis.

The

table

shows

that

the

respondents

were

evenly

divided

by

gender,

with

50%

of

the

respondents

being

male.

Age

of

the

respondents

was

spread

fairly

evenly

within

a

range

of

18

to

94

years

of

age.

The

median

age

fell

within

the

range

of

be-

tween

41

and

50

years

old.

And

respondents

over

age

66

represented

the

smallest

category

(12.7%).

The

median

income

for

the

sample

was

between

$25,001

and

$35,000

per

annum,

with

91.4%

of

respondents

reporting

a

salary

under

$75,000.

Eighty-two

percent

of

respondents

had

ob-

tained

at

least

a

high

school

education

and

50.8%

received

some

higher

education.

More

than

75%

of

respondents

had

private

health

insurance

and

slightly

less

than

one-fifth

had

Medicare.

Just

over

15%

of

the

respondents

had

Medicaid

and

10%

were

uninsured.

Fi-

nally,

nearly

two-thirds

of

respondents

re-

ported

having

a

choice

for

their

physician.

Table

2

examines

the

distribution

of

physi-

cian's

race

among

African

American

respon-

dents.

The

table

shows

that

nearly

22%

of

re-

spondents

had

an

African

American

doctor.

The

largest

percentage

of

respondents

(58.5%)

938

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

94,

NO.

11,

NOVEMBER

2002

DOCTOR

RACE

AND

PATIENT

SATISFACTION

Table

1.

Sample

Descriptive

Statistics

Variable

Percent

Male

50.0

Age

18-30

20.4

31-40

27.0

41-50

18.9

51-65

20.9

66-94

12.7

Income

<$7,500

13.2

$75,001-$15,000

12.6

$15,001-$25,000

19.3

$25,001-$35,000

1

8.6

$35,001

-$50,000

17.4

$50,001-$75,000

10.3

$75,001-$100,000

5.8

>$

100,000

2.8

Education

<HS

grad

17.7

HS

grad

31.6

Some

college

27.0

College

grad

13.8

Post

college

10.0

Insurance*

Private

75.6

Medicare

19.9

Medicaid

15.4

Uninsured

10.8

Doctor

choice

65.3

*Insurance

status

categories

are

not

mutually

exclusive.

For

example,

a

respondent

can

have

Medicare

and

a

private

healthcare

policy.

Also,

one

could

be

dually

eligible

for

Medicare

and

Medicaid.

reported

having

a

white

physician.

About

10%

of

respondents

had

Asian

or

Pacific

Islander

physicians

and

9.7%

had

a

doctor

who

was

of

Hispanic

descent

or

another

ethnic

group

(His-

panic

physicians

were

not

analyzed

as

a

sepa-

Table

2.

Race

of

Physician

Among

African

American

Respondents

who

Reported

Having

a

Usual

Source

of

Care

Physician's

race

(n=745)

White

436

(58.5%)

Black

162

(21.7%)

Hispanic/other

46

(6.5%)

Asian/pacific

islander

75

(10.1

%)

Table

3.

Logistic

Regression

Analysis

of

Predictors

of

Physician-patient

Race

Concordance,

Odds

Ratio

(95%

Confidence

Interval)

Female

B

Male

.863

(.593,1.25)

Age

18-30

B

31-40

.41

(.24,

.71)

41-50

.47

(.27,

.83)

51-65

.53

(.31,

.92)

66-94

.25

(.11,

.1)

Income

1.13

(1.0,

1.26)

Education

K-12

B

High

School

.62

(.34,

1.13)

Some

College

.73

(.39,

1

.36)

College

Graduate

.64

(.31,

1.30)

Post

College

Degree

.64

(.29,

1.38)

Insurance

Private

B

Medicare

1.43

(.75,

2.74)

Medicaid

.69

(.37,

1.32)

Uninsured

1.19

(.59,

2.39)

Doctor

Choice

1.91

(.1.00,

3.64)

Model

Statistics

Hosmer

and

Lemeshow

X2

=

4.71

df

=

8

p

=

.00

rate

category

because

their

total

numbers

were

too

small,

only

17

respondents

reported

having

a

Hispanic

physician).

Table

3

presents

the

results

of

logistic

regres-

sion

models

examining

predictors

of

race

con-

cordance.

The

table

shows

that

patient's

age,

income,

and

having

a

choice

of

physician

are

significant

predictors

of

physician-patient

race

concordance.

Younger

respondents

were

more

likely

to

be

race

concordant.

Higher

income

was

associated

with

a

greater

likelihood

of

race

concordance.

And,

respondents

who

report

they

have

the

ability

to

choose

their

own

phy-

sician

had

nearly

double

the

odds

of

being

race

concordant

with

their

physician

compared

with

patients

that

did

not

have

choice.

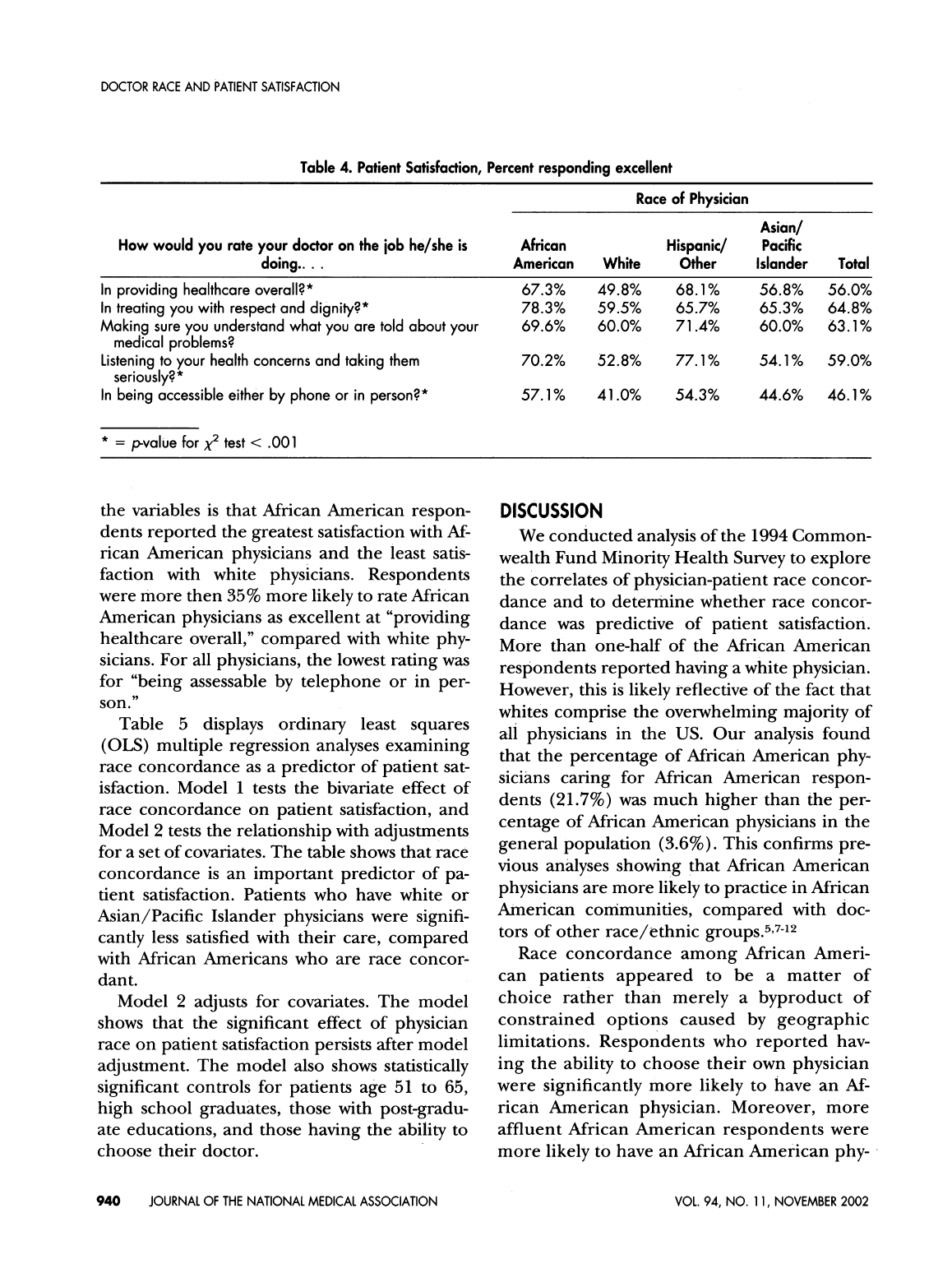

In

Table

4,

the

analysis

turns

to

an

assess-

ment

of

patient

satisfaction.

The

table

displays

bivariate

analysis

of

each

item

comprising

the

five-item

patient

satisfaction

scale

arrayed

by

race

of

physician.

The

general

pattern

among

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

94,

NO.

11,

NOVEMBER

2002

939

DOCTOR

RACE

AND

PATIENT

SATISFACTION

Table

4.

Patient

Satisfaction,

Percent

responding

excellent

Race

of

Physician

Asian/

How

would

you

rate

your

doctor

on

the

job

he/she

is

African

Hispanic/

Pacific

doing....

American

White

Other

Islander

Total

In

providing

healthcare

overall?*

67.3%

49.8%

68.1%

56.8%

56.0%

In

treating

you

with

respect

and

dignity?*

78.3%

59.5%

65.7%

65.3%

64.8%

Making

sure

you

understand

what

you

are

told

about

your

69.6%

60.0% 71.4%

60.0%

63.1%

medical

problems?

Listening

to

your

health

concerns

and

taking

them

70.2%

52.8%

77.1%

54.1%

59.0%

seriously?*

In

being

accessible

either

by

phone

or

in

person?*

57.1%

41.0% 54.3%

44.6%

46.1%

*

=

p-value

for

x2

test

<

.001

the

variables

is

that

African

American

respon-

dents

reported

the

greatest

satisfaction

with

Af-

rican

American

physicians

and

the

least

satis-

faction

with

white

physicians.

Respondents

were

more

then

35%

more

likely

to

rate

African

American

physicians

as

excellent

at

"providing

healthcare

overall,"

compared

with

white

phy-

sicians.

For

all

physicians,

the

lowest

rating

was

for

"being

assessable

by

telephone

or

in

per-

son."

Table

5

displays

ordinary

least

squares

(OLS)

multiple

regression

analyses

examining

race

concordance

as

a

predictor

of

patient

sat-

isfaction.

Model

1

tests

the

bivariate

effect

of

race

concordance

on

patient

satisfaction,

and

Model

2

tests

the

relationship

with

adjustments

for

a

set

of

covariates.

The

table

shows

that

race

concordance

is

an

important

predictor

of

pa-

tient

satisfaction.

Patients

who

have

white

or

Asian/Pacific

Islander

physicians

were

signifi-

cantly

less

satisfied

with

their

care,

compared

with

African

Americans

who

are

race

concor-

dant.

Model

2

adjusts

for

covariates.

The

model

shows

that

the

significant

effect

of

physician

race

on

patient

satisfaction

persists

after

model

adjustment.

The

model

also

shows

statistically

significant

controls

for

patients

age

51

to

65,

high

school

graduates,

those

with

post-gradu-

ate

educations,

and

those

having

the

ability

to

choose

their

doctor.

DISCUSSION

We

conducted

analysis

of

the

1994

Common-

wealth

Fund

Minority

Health

Survey

to

explore

the

correlates

of

physician-patient

race

concor-

dance

and

to

determine

whether

race

concor-

dance

was

predictive

of

patient

satisfaction.

More

than

one-half

of

the

African

American

respondents

reported

having

a

white

physician.

However,

this

is

likely

reflective

of

the

fact

that

whites

comprise

the

overwhelming

majority

of

all

physicians

in

the

US.

Our

analysis

found

that

the

percentage

of

African

American

phy-

sicians

caring

for

African

American

respon-

dents

(21.7%)

was

much

higher

than

the

per-

centage

of

African

American

physicians

in

the

general

population

(3.6%).

This

confirms

pre-

vious

analyses

showing

that

African

American

physicians

are

more

likely

to

practice

in

African

American

communities,

compared

with

doc-

tors

of

other

race/ethnic

groups.5,7-'2

Race

concordance

among

African

Ameri-

can

patients

appeared

to

be

a

matter

of

choice

rather

than

merely

a

byproduct

of

constrained

options

caused

by

geographic

limitations.

Respondents

who

reported

hav-

ing

the

ability

to

choose

their

own

physician

were

significantly

more

likely

to

have

an

Af-

rican

American

physician.

Moreover,

more

affluent

African

American

respondents

were

more

likely

to

have

an

African

American

phy-

940

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

94,

NO.

11,

NOVEMBER

2002

DOCTOR

RACE

AND

PATIENT

SATISFACTION

Table

5.

Ordinary

Least

Squares

(OLS)

Regression

of

Predictors

of

Patient

Satisfaction-race/Ethnic

Specific

Analysis,

Standardized

Coefficient

(P-value)

Model

1

Model

2

Physician

race

Black

White

-.166

(p

=

.0001)

-.55

(p

=

.0002)

Asian/pacific

islander

-.093

(p

=

.02)

-.098

(p

=

.02)

Hispanic/other

.026

(p

=

.53)

.031

(p

=

.44)

Female

B

Male

-

.024

(p

=

.53)

Age

18-30

31-40

.016

(p

=

.75)

4

1-50

.037

(p

=

.45)

51-65

.128(p=

.011)

66-94

.046

(p

=

.44)

Income

.023

(p=

.61)

Education

K-12

High

school

graduate

.115

(p

=

.04)

Some

college

.088

(p

=

.13)

College

graduate

.039

(p

=

.46)

Post

graduate

degree

.131

(p

=

.012)

Insurance

Private

B

Medicare

.045

(p

=

.42)

Medicaid

.001

(p

=

.98)

Uninsured

.059

(p

=

.13)

Patient

does

not

have

ability

to

choose

doctor

B

Patient

has

ability

to

choose

doctor

.169

(p

=

.0001)

Model

statistics

Adj

R2

=

.024

Adj

R2

=

.064

F

=

6.69

F

=

3.83

p

=.000

p

=.000

sician,

compared

with

less

affluent

persons.

These

respondents,

presumably,

have

a

greater

choice

of

providers.

While

physician-patient

race

concordance

leads

to

greater

patient

satisfaction,

there

is

room

for

improvement.

As

Table

4

shows,

Af-

rican

American

respondents

were

more

satis-

fied

with

Hispanic

and

other

race

physicians

at

making

sure

patients

understood

what

they

were

being

told

and

listening

to

patient's

health

concerns

and

taking

them

seriously.

Ad-

ditionally,

only

57.1%

of

respondents

reported

that

African

American

physicians

were

doing

an

excellent

job

at

being

accessible

by

tele-

phone

or

in

person.

We

point

out

that

the

Hispanic/other

physician

category

is

somewhat

of

a

miscellaneous

category,

so

findings

related

to

this

group

must

be

interpreted

with

caution.

However,

it is

meaningful

that

African

Ameri-

can

physicians

did

not

obtain

the

highest

rat-

ings

for

all

categories.

Moreover,

Chen

et

al.,13

demonstrated

that

African

American

physi-

cians

were

as

likely

as

white

physicians

to

fail

to

refer

African

American

cardiac

patients

for

cor-

onary

Angiography

when

the

procedure

was

indicated.

Thus,

while

African

American

pa-

tients

are

more

satisfied

with

their

care,

it

is

not

clear

that

all

dimensions

of

quality

are

en-

hanced

by

race

concordance.

For

example,

are

African

Americans

more

likely

to

receive

pre-

ventive

health

services?

Are

their

health

ser-

vices

utilization

patterns

different?

Is

their

com-

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

94,

NO.

11,

NOVEMBER

2002

941

DOCTOR

RACE

AND

PATIENT

SATISFACTION

pliance

better?

These

questions

remain

to

be

explored

in

future

research.

Nevertheless,

in

spite

of

some

shortcomings

in

satisfaction

among

race

concordant

African

Americans,

our

finding

of

greater

patient

satis-

faction

supports

the

need

for

the

continuation

of

efforts

to

increase

African

American

physi-

cian

production.

One

might

interpret

these

results

as

support-

ing

a

return

to

racial

segregation

in

medicine;

that

is,

that

patients

are

better

off

with

physi-

cians

who

are

of

their

own

racial

or

ethnic

group.

However,

we

would

strenuously

resist

this

interpretation.

Instead,

we

favor

providing

patients

with

an

array

of

options

that

maxi-

mizes

choice,

and

we

view

the

race

of

physician

as

merely

one

factor

to

be

considered

among

many

others.

As

Table

5

shows,

patient

choice

is

also

highly

associated

with

patient

satisfac-

tion.

As

to

the

matter

of

whether

increasing

the

number

of

African

American

physicians

will

lead

to

better

health

outcomes

for

African

Americans,

an

interpretation

of

our

findings

within

the

context

of

other

related

literature

leads

us

to

conclude

that

it

most

likely

will.

Increasing

the

number

of

African

American

physicians

will

expand

the

opportunities

for

African

American

patients

who

choose

to

be

race

concordant.

Our

findings

suggest

that

there

will

be

greater

satisfaction

among

African

Americans

who

are

inclined

to

choose

doctors

in

concordance

with

race.

Previous

findings

demonstrate

that

African

American

physicians

are

more

likely

to

practice

in

minority

and

under-served

communities.7-"1

Studies

of

patient

satisfaction

and

other

related

concepts

(such

as

patient-centeredness)

find

improved

outcomes

in

race

concordant

physi-

cian-patient

pairs.'6

There

is

a

very

limited

lit-

erature

on

race

concordance

and

medical

out-

comes,'3

but

the

one

available

study

indicates

that

African

American

physicians

are

as

likely

as

white

physicians

to

under-refer

African

Ameri-

can

patients

for

heart

surgery.

Chen's'3

find-

ings

are

inconsistent

with

the

findings

in

the

present

analysis,

as

well

as

other

studies,'6"7

and

may

be

anomalous.

Clearly,

there

is

a

need

for

further

study

to

confirm

or

refute

Chen's

findings.

However,

whether

or

not

future

re-

search

confirms

Chen,

patient

satisfaction

is

an

important

outcome

in

its

own

right.

In

addition

to

its

intrinsic

importance

for

individual

health-

care

consumers

and

third-party

payers,

patient

satisfaction

also

is

an

important

determinant

of

health-related

outcomes,

such

as

health

ser-

vices

utilization,'8'19

decision

to

switch

to

an-

other

health

plan,2s23

compliance

with

medical

regimen,24

and

the

decision

to

initiate

malprac-

tice

suits.25

Moreover,

the

Institute

of

Medicine

recommends

including

patient

satisfaction

as

an

indicator

of

quality

of

care.26'27

As

the

African

American

population

contin-

ues

to

grow

and

becomes

increasingly

affluent,

the

demand

for

African

American

physicians

will

grow,

as

well.

However,

as

previous

analyses

have

shown,

the

current

rate

of

African

Amer-

ican

physician

production,

will

not

keep

pace

with

future

demand.5

As

such,

alternatives

such

as

effective

"cultural

competency"

training,

are

needed

if

we

are

to

achieve

the

objective

of

eliminating

race

disparities

in

health,

improve

quality

of

care

among

African

American

pa-

tients,

and

make

the

healthcare

system

respon-

sive

to

the

changing

racial

demographics

of

our

nation.

AKNOWLEDGEMENT

This

research

was

supported

by

a

grant

from

the

Com-

monwealth

Fund

to

Dr.

LaVeist.

REFERENCES

1.

Gamble

VN.

A

legacy

of

distrust:

African

Americans

and

medical

research.

Am

JPrev

Med.

1993;9(6

Suppl):35-38.

2.

Smith

DB.

Health

Care

Divided:

Race

and

Healing

a

Nation.

Ann

Arbor,

MI:

University

of

Michigan

Press,

1999.

3.

Mayberry

RM,

Mili

F,

Ofili

E.

Racial

and

ethnic

differ-

ences

in

access

to

medical

care.

Med

Care

Res

Rev.

2000;57(Suppl

1):108-145.

4.

Carlisle

DM,

Gardner

JE,

Honghu

Liu.

The

entry

of

underrepresented

minority

students

into

US

medical

schools:

an

evaluation

of

recent

trends.

AmJPub

Hlth.

1998;88:1314-1318.

5.

Libby

DL,

Zhou

Z,

Kindig

DA.

Will

minority

physician

supply

meet

US

needs?

Health

Affairs.

1997;16:205-214.

6.

Hogue,

Carol

JR,

Hargraves

MA.

The

Commonwealth

Fund

Minority

Health

Survey

of

1994:

an

overview,

in

Carol

JR,

Hogue,

Hargraves

MA

and

Collins

KS

(eds.),

Minority

health

in

America:

findings

and

policy

implications

from

the

Commonwealth

Fund

942

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

94,

NO.

11,

NOVEMBER

2002

DOCTOR

RACE

AND

PATIENT

SATISFACTION

Minority

Health

Survey,

Baltimore

and

London:

Johns

Hopkins

University

Press,

2000.

7.

Cantor

JC,

Miles

EL,

Baker

LC,

Barker

DC.

Physician

service

to

the

underserved:

implications

for

affirmative

action

in

medical

education.

Inquiry.

1996;33:167-180.

8.

Komaromay

M,

Grumbach

K,

Drake

M,

et

al.

The

role

of

Black

and

Hispanic

physicians

in

providing

health

care

for

un-

derserved

populations.

New

EngJ

Med.

1996;334:1305-1310.

9.

Moy

E,

Bartman

BA.

Physician

race

and

care

of

minority

and

medically

indigent

patients.

JAMA.

1995;273:1515-1520.

10.

Keith

SN,

Bell

RM,

Swanson

AG,

Williams

AP.

Effects

of

affirmative

action

in

medical

schools:

a

study

of

the

class

of

1975.

New

EngJMed.

1985;313:1519-1525.

11.

Lloyd

SM

Jr.,

Johnson

DG.

Practice

patterns

of

Black

physicians:

results

of

a

survey

of

Howard

University

College

of

Medicine

alumni.

J

Nat

Med

Assoc.

1982;74:129

-141.

12.

Rocheleau

B.

Black

physicians

and

ambulatory

care.

Pub

Hlth

Repts.

1978;93:278-282.

13.

Chen

J,

Rathore

SS,

Radford

MJ,

Wang

Y,

Krumholz

HM.

Racial

differences

in

the

use

of

cardiac

catheterization

after

acute

myocardial

infarction.

New

EnglJMed.

2001;344:1443-1449.

14.

Geiger

HJ.

Racial

and

ethnic

disparities

in

diagnosis

and

treatment:

a

review

of

the

evidence

and

a

consideration

of

causes.

In

Unequal

Treatment;

Confronting

Racial

and

Ethnic

Disparities

in

Health

Care.

2002

IOM.

Washington,

DC:

National

Academy

Press.

15.

Kressin

NR,

Peterson

IA.

Racial

differences

in

the

use

of

invasive

cardiovascular

procedures:

review

of

the

literature

and

prescription

for

future

research.

Ann

Intern

Med.

2001;135:352-

366.

16.

Cooper-Patrick

L,

Gallo

Jj,

Gonzales

Jj,

et

al.

Race,

gen-

der,

and

partnership

in

the

patient-physician

relationship.JAMA.

1999;282:583-589.

17.

Saha

S,

Komaromy

MM,

Koepsell

RD,

Bindman

AB.

Patient-physician

racial

concordance

and

the

perceived

quality

and

use

of

health

care.

Arch

Int

Med.

1999;159:997-1004.

18.

Zastoway

TR,

Roghmann

KJ,

Cafferata

GL.

Patient

satis-

faction

and

the

use

of

health

services:

explorations

in

causality.

Med

Care.

1989;27:705-723.

19.

Roghmann

KJ,

Hengst

A,

Zastoway

TR.

Satisfaction

with

medical

care:

its

measurement

and

relation

to

utilization.

Med

Care.

1979;17:461-479.

20.

Murray

BP,

Dwore

RB,

Gustafson

G,

Parsons

RJ,

Vor-

derer

LH.

Enrollee

satisfaction

with

HMOs

and

its

relationship

with

disenrollment.

Managed

Care

Interface.

2000;13:55-61.

21.

Allen

HM

Jr.,

Rogers

WH.

The

consumer

health

plan

value

survey:

round

two.

Hlth

Aff

1998;17:265-268.

22.

Hennelly

VD,

Boxerman

SB.

Disenrollment

from

a

pre-

paid

group

plan:

a

multivariate

analysis.

Med

Care.

1983;21:1154-

1167.

23.

Sorensen

AA,

Wersinger

RP.

Factors

influencing

disen-

rollment

from

an

HMO.

Med

Care.

1981;19:766-773.

24.

Smith

NA,

Ley

P,

Seale

JP,

Shaw

J.

Health

benefits,

satisfaction

and

compliance.

Pat

Educ

Counsel.

1987;10:279-286.

25.

Penchansky

R,

Macnee

C.

Initiation

of

medical

malprac-

tice

suits:

a

conceptualization

and

test.

Med

Care.

1996;34:280-

282.

26.

Hurtado

MP,

Swift

EK,

CorriganJM

(Eds.).

Envisioning

the

National

Health

Care

Quality

Report.

2001

IOM.

Washington

DC:

National

Academy

Press.

27.

Institute

of

Medicine,

Committee

on

Quality

of

Health

Care

in

America.

Crossing

the

Quality

Chasm:

A

New

Health

System

for

the

21st

Century

2001.

IOM.

Washington

DC:

National

Acad-

emy

Press.

28.

LaVeist

TA,

Nuru-Jeter

A.

Is

doctor-patient

race

concor-

dance

associated

with

greater

satisfaction

with

care?

J

Hlth

Soc

Behv.

(forthcoming)

We

Welcome

Your

Comments

Journal

of

the

National

Medical

Association

welcomes

your

Letters

to

the

Editor

about

articles

that

appear

in

the

JNMA

or

issues

relevant

to

minority

health

care.

Address

correspondence

to

Editor-in-Chief,

]NMA,

1012

Tenth

St,

NW,

Washington,

DC

20001;

fax

(202)

371-1162;

or

ktaylor

@nmanet.org.

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

94,

NO.

1

1,

NOVEMBER

2002

943