NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

THE FUTURE OF THE GOVERNMENT SPONSORED ENTERPRISES:

THE ROLE FOR GOVERNMENT IN THE U.S. MORTGAGE MARKET

Dwight Jaffee

John M. Quigley

Working Paper 17685

http://www.nber.org/papers/w17685

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

December 2011

We are grateful to the Fisher Center for Real Estate and Urban Economics at the University of California,

Berkeley, for financial support. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-

reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official

NBER publications.

© 2011 by Dwight Jaffee and John M. Quigley. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed

two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice,

is given to the source.

The Future of the Government Sponsored Enterprises: The Role for Government in the U.S.

Mortgage Market

Dwight Jaffee and John M. Quigley

NBER Working Paper No. 17685

December 2011

JEL No. G01,G2,G28,H81,R21,R3

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes options for reforming the U.S. housing finance system in view of the failure of

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as government sponsored enterprises (GSEs). The options considered

include GSE reform, a range of possible new governmental mortgage guarantee plans, and greater

reliance on private mortgage markets. The analysis also considers the likely consequences of adopting

alternative roles for government in the U.S. housing and mortgage markets. We start by reviewing

the history of the GSEs and their contributions to the operation of U.S. housing and mortgage markets,

including the actions that led to their failure in conjunction with the recent mortgage market crisis.

The reform options we consider include those proposed in a 2011 U.S. Treasury White Paper, plans

for new government mortgage guarantees from various researchers and organizations, and the evidence

from Western European countries for the efficacy of private mortgages markets.

Dwight Jaffee

Haas School of Business

University of California

Berkeley, CA 94720-1900

John M. Quigley

Department of Economics

Evans Hall #3880

University of California

Berkeley, CA 94720-3880

2

I. Introduction

The two large Government Sponsored Housing Enterprises (GSEs),

1

the Federal

National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage

Corporation (“Freddie Mac”), evolved over three quarters of a century from a single

small government agency, to a large and powerful duopoly, and ultimately to insolvent

institutions protected from bankruptcy only by the full faith and credit of the U.S.

government. Between 2007 and Q2 2011, the two GSEs had realized losses of $247

billion, and they required draws of $169 billion under the Treasured Preferred Stock

Purchase Agreements to remain in operation. (See Federal Housing Finance Agency

2011). This paper traces the transformation of the GSEs from privately held institutions

with powerful direction and political influence to vassals reporting to an administrative

agency in the Department of Housing and Urban Development (the Federal Housing

Finance Agency, FHFA).

Within the next few years, the agencies will have to be restructured. Proposals for

reform include recapitalizing them in some form as Government Sponsored Enterprises

(GSEs), reconstituting them as agencies of the federal government with more narrowly-

specified missions, or privatizing the organizations. There are also proposals to replace

the GSEs with a variety of new government mortgage guarantee/insurance programs. The

GSE reform and mortgage guarantee proposals are both nested within the larger question

of what are the likely consequences of alternative roles for government in the U.S.

housing and mortgage markets. This paper is intended to help in the deliberations about

1

A third, much smaller, Government Sponsored Housing Enterprise is the Federal Home Loan Bank

System (FHLBS). The issues for reforming the FHLBS are similar to many of the issue raised in this paper

for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, although we have not analyzed separately the FHLBS or other non-

housing government enterprises.

3

“what to do” about these costly failures. We briefly review the history of the housing

enterprises and their performance, including the recent housing crisis. We document the

contributions of Freddie and Fannie to the operation of U.S. housing markets, and we

analyze the role of the agencies in the recent housing crisis. We search for evidence on

the importance of Freddie and Fannie in achieving other important housing goals. We

compare U.S. policies with those adopted in other developed countries.

This is not the first time we have provided some analysis of the reform options in

housing finance, either individually (Jaffee, 2010b, 2011; Quigley 2006) or jointly (Jaffee

and Quigley, 2010). However, it is our first attempt to consider all the history and all of

the options.

In section II below we discuss the background and origin of the GSEs and of the

federal role in supplying housing credit. Section III provides a brief summary of

homeownership and government policy. Section IV describes the broader objectives and

goals of the GSE institutions and analyzes the most recent failures of the credit market

and the secondary housing market. Section V links the current housing crisis to the

insolvency of credit institutions. Section VI describes likely the consequences of a series

of plans concerning the restructuring of these institutions and alternative mechanisms for

government support of the U.S. mortgage market. It also provides a brief summary of the

GSEs under their government conservatorship since September 2008.

II. Background

With the public sale of its stock and its conversion into a government sponsored

enterprise in 1968, the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) emerged from

obscurity as an agent in the market for home mortgage credit. The FNMA had been

4

established in 1938, based on provisions in the 1934 National Housing Act, after the

collapse of the housing market during the Great Depression. The 1934 Act had

established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to oversee a program of home

mortgage insurance against default. Insurance was funded by the proceeds of a fixed-

premium charged on unpaid loan balances. These revenues were deposited in Treasury

securities and managed as a mutual insurance fund. Significantly, default insurance was

offered on “economically sound” self-amortizing mortgages with terms as long as twenty

years and with loan-to-value ratios up to eighty percent.

Diffusion of the new FHA product across the country required national

standardization of underwriting procedures. Appraisals were required, and borrowers’

credit histories and financial capacities were reported and evaluated systematically. The

Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund, established to manage the reserve of FHA premiums,

was required to be actuarially sound. This was generally understood to allow very small

redistributions from high income to low income FHA mortgagees. By its original design,

the FHA was clearly intended to serve the vast majority of homeowners.

In the 1934 Act, Congress had also sought to encourage private establishment of

National Mortgage Associations that would buy and sell the new and unfamiliar insured

mortgages of the Federal Housing Administration. By creating a secondary market for

these assets, the Associations sought to increase the willingness of primary lenders to

make these loans. No private associations were formed, however. When further

liberalization of the terms under which associations could be organized was still

unsuccessful, the Federal National Mortgage Association was chartered in 1938 by the

Federal Housing Administrator following the request of the President of the United

5

States. Federal action was precipitated particularly by concern over the acceptability of

new FHA ninety-percent twenty-five-year loans authorized that year.

At first, the Association operated on a small scale, but its willingness to buy FHA

mortgages encouraged lenders to make them. A 1948 authorization to purchase

mortgages guaranteed by the Veterans Administration led the Association to make

purchases, commitments, loans, and investments that soon approached the

congressionally authorized limit of $2.5 billion. Since the maximum interest rate on VA

mortgages was below the market rate, FNMA’s advance commitments to buy VA-

guaranteed mortgages at par assured windfall gains to private borrowers or lenders. The

1954 Housing Act reorganized Fannie Mae as a mixed-ownership corporation with

eligible shareholders being the federal government and lenders that sold mortgages to

Fannie Mae. FNMA was then able to finance its operations through sale of its preferred

stock to the U.S. Treasury, through sale of its common stock to lenders whose mortgages

it bought, and by the sale of bonds to the public.

The Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968 transferred FNMA’s special

assistance and the management and liquidation of part of its portfolio to the newly

constituted Government National Mortgage Association. Its secondary market operations

remained with FNMA, now owned entirely by private stockholders. Commercial banks

were the primary beneficiaries of FNMA’s secondary market activities in FHA and VA

mortgages -- since the banks specialized in originating the government-guaranteed

mortgages. In contrast, the mortgages originated by Savings and Loan Associations

(S&Ls) and Mutual Savings Banks (“Thrift Institutions”) were primarily “conventional”

mortgages, meaning they received no government guarantee. The thrift institutions

6

lobbied for equal treatment, and were rewarded in 1970 with the establishment of the

Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (“Freddie Mac”) under the regulatory control

of the Federal Home Loan Bank System, the S&L regulator. Freddie Mac stock first

became publicly available in 1989, although shares owned by Freddie Mac’s financial

partners had been traded on the New York Stock Exchange starting in 1984.

III. Homeownership and Government Policy

According to de Tocqueville (1835), Americans have long been obsessed with

owner-occupied housing. Richard Green (2011) sees this as a political issue, as societies

are less disposed to make revolution when personal and real property is augmented and

distributed among the population. Other recent work emphasizes the external benefits of

owner-occupied housing, and a large social science literature has developed exploring the

connection between higher levels of homeownership and the economic and social

outcomes of households. Appendix Table A1 reports some of the findings linking

homeownership to social outcomes. Two other papers (Dietz and Haurin, 2003; Haurin,

Dietz and Weinberg, 2002) provide an exhaustive comparison of the economic and social

consequences for those living in owner-occupied and rental housing.

Most of the research supports the conclusion that homeownership has some

positive effects upon the social outcomes for individuals and households. But the

research does not conclude that the effect is very large. But even if the effect were large,

nothing supports the conclusion that homeownership should be supported by the

institution of the GSEs or their policy choices. In particular, the primary impact of

instruments that focus on lowering the cost or expanding the availability of mortgages

7

will be larger mortgages, which makes those instruments ineffective and costly relative to

direct subsidies for homeownership.

This is important -- for as noted below many of the popular arguments in support

of subsidies for the GSEs are based upon the promotion of homeownership in the

economy.

IV. Policy Objectives for the GSEs

A. Primary Objectives

The GSE charters are quite explicit in stating the goals and responsibilities of the

enterprises, but they do not state homeownership goals directly. Instead, they seek to:

1) provide stability in the secondary market for residential mortgages;

2) respond appropriately to the private capital market;

3) provide ongoing assistance to the secondary market for residential mortgages

(including activities relating to mortgages on housing for low- and moderate-income

families involving a reasonable economic return that may be less than the return earned

on other activities) by increasing the liquidity of mortgage investments and improving the

distribution of investment capital available for residential mortgage financing;

4) promote access to mortgage credit throughout the Nation (including central cities,

rural areas, and underserved areas) by increasing the liquidity of mortgage investments

and improving the distribution of investment capital available for residential mortgage

financing; and

5) manage and liquidate federally owned mortgage portfolios in an orderly manner,

with a minimum of adverse effect upon the residential mortgage market and minimum

loss to the Federal Government.

8

This section reviews the key activities of the GSEs with respect to providing

stability, assistance, and liquidity to the secondary market for residential mortgages. The

specific objectives of the secondary market activities have varied over time, including

operations to reinforce or offset fiscal and monetary policy, to increase residential

construction, to make a market in federally underwritten mortgages, to reduce regional

yield differentials, and to act as a mortgage lender of last resort. (See Guttentag, 1963, for

an extensive discussion of these key activities.)

A.1 Quantitative Impact of the GSEs on the U.S. Home Mortgage Market

Table 1 reviews the quantitative role of the GSEs in the US mortgage market over

the recent past. The top panel reports the outstanding amounts of whole home mortgages

at the end of each decade from 1950 through 2010. Through 1960, all whole home

mortgages were directly held in portfolios, and even by 1970 the only exception was $3

billion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) issued by the newly established

Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA). The largest portfolio investor has

always been the set of depository institutions, commercial banks and thrift institutions

(savings and loan associations, savings banks, and credit unions).

2

The market investor

portfolios include capital market investors ranging from pension funds and mutual funds

to insurance companies. Starting in 1980, increasing amounts of whole home mortgages

have been held within MBS pools. The top panel of Table 1 separates the three main

categories of MBS pools: pools issued by the GSEs, by GNMA, and by private label

securitizers (PLS).

2

The GSE category covers the Fannie Mae on-balance-sheet portfolio through 1970 and the sum of the

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac portfolios thereafter.

9

The middle panel of Table 1 shows each of the investor categories for whole

home mortgage holdings as a percentage of the total amount outstanding. One major

trend is apparent; portfolio holdings declined steadily from 100 percent of the total in

1960 to 37 percent of the total by 2010. Among the portfolio investors, both depository

institution and market investor holdings declined steadily starting in 1970. The GSE

portfolio holdings of whole home mortgages, five percent of the total in 2010, remained a

small percentage of the total throughout the history, with fluctuations within the narrow

band of three percent to eight percent of the total.

The second major trend reported in the middle panel of Table 1 is the steady rise

in mortgage pool holdings as a percentage of the total, starting at one percent in 1970 and

reaching 63 percent of the total by 2010. GSE pools show the most rapid rise, reaching 41

percent of total outstanding home mortgages by 2010. The PLS pools also grew steadily,

reaching twelve percent of the total by 2010. The GNMA pool share of total outstanding

mortgages, ten percent at year-end 2010, fluctuated in a narrow range between ten

percent and fifteen percent of the total from 1980 to the present.

The bottom panel of Table 1 shows the direct GSE share of the home mortgage

market, computed as the sum of whole mortgages held in the GSE portfolios and their

outstanding MBS. While this GSE share rose steadily from 1950, the primary increase

started in 1990, with the share reaching 46 percent of all outstanding home mortgages in

2010. This direct share does not include MBS from other issuers that were held in the

GSE portfolios, a topic to which we turn below.

3

3

Quantitatively, including the GSE holdings of other MBS would raise the total GSE share to 47 percent

and 48 percent for 2000 and 2010 respectively. This ratio actually peaked in 2003, reaching fifty percent.

10

While Table 1 accounts for all outstanding home mortgages, it does not

distinguish among the investor groups holding the MBS instruments created by the

mortgage pools. This issue is addressed in Table 2, in which ownership of the MBS pools

has been allocated among the various investor classes. These values are then combined

with the portfolio holdings of whole mortgages to determine the ownership structure of

all home mortgages, whether held as whole mortgages or as investment in MBS pools.

4

It

is apparent from Table 2 that, starting in 1980, market investors were expanding relative

to the depository institutions and the GSEs, and that by 2010 the market investors were

the largest investor class for the sum of whole mortgages and mortgage securities.

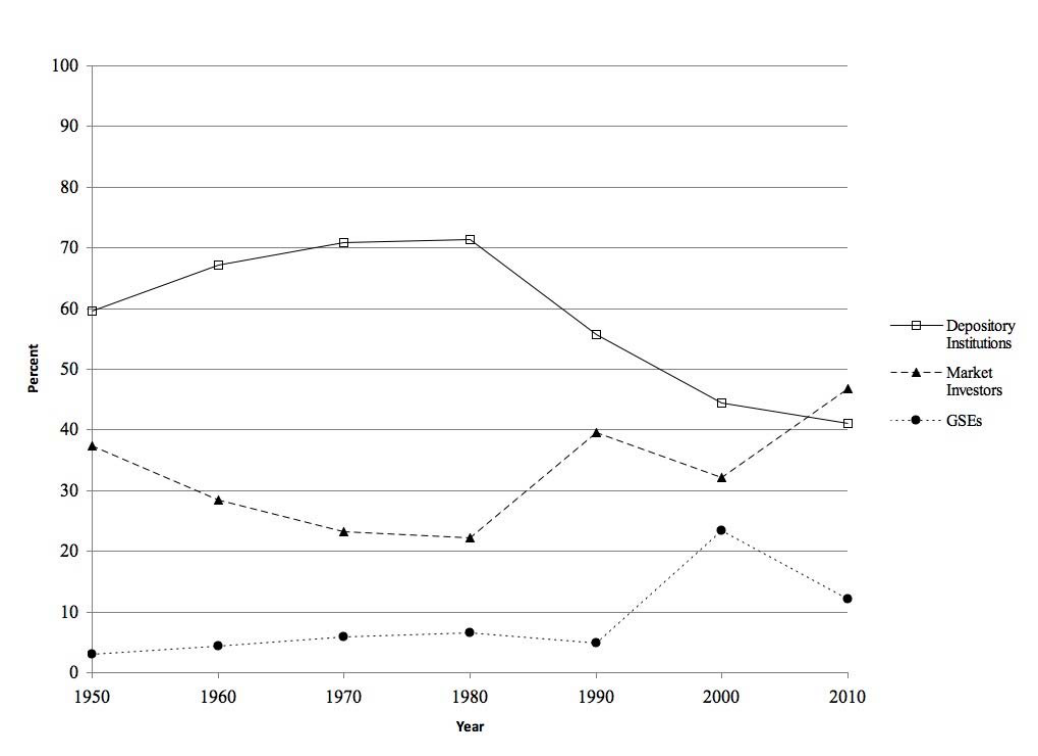

Figure 1 reports the percentage of outstanding whole mortgages held directly in

portfolios for each of the three investor classes. The depository institutions have always

been the predominant holder of whole mortgages. At year-end 2010, the depository

institutions held 76 percent of all whole mortgages that were directly held in portfolios,

with the market investors and the GSEs each holding a twelve percent share.

Figure 2 reports the percentage of outstanding MBS for the three holder classes.

5

It is apparent that the market investors have always been dominant in holding MBS

positions. At year-end 2010, market investors were holding 67 percent of the outstanding

MBS, with depository institutions holding 21 percent and the GSEs twelve percent.

Figure 3 combines the results for Figures 1 and 2, reporting the share for each

holder class of their combined positions in whole mortgages and MBS. By 2010, the

market investors had the largest position, representing 47 percent of all home mortgages,

4

As far as we are aware, this integration of whole mortgage portfolio holdings and MBS pools by investor

has not been available previously.

5

The graphs start in 1970, since there were no outstanding MBS before that year.

11

with depository institutions in the second position, holding 41 percent of all home

mortgages. At the same time, the GSEs were holding twelve percent of all home

mortgages (as either whole mortgages or MBS) a share just below their average over the

last three decades.

Figure 3 indicates that the GSE combined holdings of whole mortgages and MBS

has always represented a relatively small share of total U.S. home mortgages outstanding.

In this sense, closing the GSEs now, in an orderly way, would have a minor impact on the

U.S. mortgage market. That is, the twelve percent GSE share could be readily replaced by

a combination of market investors and depository institutions (who are already holding

88 percent of U.S. home mortgages). There are, however, two other measures of potential

GSE benefits with regard to outstanding whole mortgages and MBS: (1) the contribution

of MBS issued by the GSEs, and (2) stabilization of the U.S. home mortgage market

through countercyclical activities by the GSEs. We now consider these in turn.

A.2 The Role of GSE-Issued MBS

Figure 4 shows the relative shares of outstanding home mortgage MBS by issuer

class. The GSE share has been dominant since 1990, representing 65 percent of all

outstanding MBS in 2010. The share of private label securitizers (PLS) has been steadily

rising, but still represented only 19 percent of outstanding MBS at year-end 2010. The

GNMA share has been steadily declining, reaching a 16 percent market share by year-end

2010.

The dominant historical position of GSE MBS in the current U.S. home mortgage

is sometimes used to justify a future role for the GSEs in the market. But, at its core, the

GSE dominance of the MBS market for home mortgages has been largely derived from

12

the assumption of market investors—reinforced by GSE marketing--that the GSE MBS

had an implicit government guarantee (and which turned out to be correct, after

imposition of the GSE Conservatorships in 2008). In this sense, the dominant GSE MBS

position is just an example of crowding out, whereby any asset with a low-cost

government guarantee against loss will likely replace private activity in the same market.

If the government guarantee were eliminated, there is every reason to expect that private

market activity would simply replace the activity of the government entity.

A brief review of the history of U.S. MBS development is valuable for

understanding the limited contribution of the GSEs to MBS innovations:

6

1968: GNMA creates first modern MBS by securitizing FHA/VA mortgages;

1970s: GSEs expand MBS market based on their implicit government guarantee;

7

1980s: Salomon Bros. securitizes multi-class, non-guaranteed, MBS instruments;

8

1990s: Multi-class (structured finance) mechanism is first applied to wide range of

asset-backed securities, including auto, credit card, and commercial mortgage loans;

2000s: Subprime lending becomes the most important application of MBS/ABS

methods.

6

US mortgage securitization probably actually began soon after the founding of the Republic. Following

the war of 1812, the US federal government was desperate for revenue and extended loans to homesteaders

for property on the Western frontiers. Without the resources to make and hold these loans, the government

pooled and sold these loans to investors. By the 1920s, securitization was already a well accepted format

for selling loans to investors. These mortgage-backed securities failed during the real estate crisis of the

1930s, and it was decades before U.S. securitization was reactivated in 1968. See Quinn (2010) for a new

history of the U.S. housing policy and the origins of securitization.

7

The GSEs could point to their $2.25 billion line of credit at the US Treasury as backing for their

guarantee, a significant factor only in the early years when their scale of operations was relatively small. It

also helped the GSE case that the US government never firmly and officially rejected the notion of an

implicit guarantee.

8

The colorful development of private-label MBS under Lewis Ranieri at Solomon Brothers is wonderfully

chronicled in Liars Poker by Lewis (1990).

13

Credit for the modern innovation of single-class MBS belongs to the government

itself with the creation of the GNMA MBS. GNMA was, and remains, an agency within

the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Likewise, credit for the innovation

of the multi-class MBS belongs to the private sector with the development of structured

MBS by Salomon Bros. in the 1980s. In fact, the GSEs have always been followers, not

innovators, in the MBS market. The success of the GSEs in establishing the market for

their own MBS depended entirely on the perception of capital market investors that they

faced no credit risk as the result of the implicit federal guarantee. Absent this government

guarantee, the single-class GSE MBS would have simply lost out in the marketplace to

the multi-class, private-label, MBS.

GSE proponents often argue that the GSEs reduced securitization costs and

mortgage interest rates. Here, too, the reality is that the GSEs provide no benefit other

than the implicit guarantee. A case in point is the TBA (“to be announced”) forward

market for GSE and GNMA MBS. While this market arguably expands the liquidity of

the traded MBS, the benefit depends completely on the market’s perception that the

guarantees—explicit for GNMA and implicit for the GSE MBS—make credit risk

irrelevant in the pricing and trading of the securities. It is equally noteworthy that the

markets for asset-backed securitization, for the securitization of credit card, auto, and

commercial mortgage loans, and other loan classes as well, expanded rapidly starting in

the early 1990s without any contribution from the GSEs. Indeed, as with the original

GNMA MBS, the GSEs benefited from the innovation by others, creating their own

14

structured finance offerings once the market demand for such securities had been

expanded through private market innovation.

9

Finally, the claim is sometimes made that the GSE MBS activity is critical for the

survival of the thirty-year, fixed-rate, residential mortgage. This claim is unwarranted. In

fact, two features of the GSE MBS instrument were clearly detriments to the expansion

of the long-term, fixed-rate, mortgage:

First, the GSE MBS transferred the entire interest rate risk imbedded in the fixed-

rate mortgages to the market investors who purchased the instruments. The GSEs took no

action to mitigate this risk;

Second, the GSE MBS generally disallowed prepayment penalties on all the

mortgages they securitized. While borrowers may have felt they benefitted from this

“free” call option, it greatly magnified the interest rate risk imposed on investors in the

GSE MBS, and led to higher interest rates on the fixed-rate mortgages.

Finally, a number of Western European countries successfully use long-term,

fixed rate, mortgages, but have no entity comparable to the GSEs, Denmark is the most

conspicuous example. The use of covered bonds allows European banks to hold long-

term mortgages on their balance sheets, while passing a substantial part of the interest-

rate risk to capital market investors. We further discuss the experience of Western

European countries in Section A5 below.

9

See Downing, Jaffee, and Wallace (2009) for a discussion of how the GSEs profited by restructuring their

simple passthrough MBS into more complex multi-tranche securitizations.

15

A.3 The Limited GSE Contributions to Mortgage Market Stability

The GSEs also claim credit for taking actions to stabilize the U.S. mortgage

markets. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (2009), however, finds little

evidence of such benefits:

“… the extent to which the enterprises have been able to support a stable

and liquid secondary mortgage market during periods of economic stress,

which are key charter and statutory obligations, is not clear. In 1996, we

attempted to determine the extent to which the enterprises’ activities

would support mortgage finance during stressful economic periods by

analyzing Fannie Mae’s mortgage activities in some states, including oil

producing states such as Texas and Louisiana, beginning in the 1980s.

Specifically, we analyzed state-level data on Fannie Mae’s market shares

and housing price indexes for the years 1980–1994. We did not find

sufficient evidence that Fannie Mae provided an economic cushion to

mortgage markets in those states during the period analyzed.”

Reports by the Congressional Budget Office (1996, 2010) come to similar conclusions.

The academic literature also generally concludes that the GSE contribution to U.S.

mortgage market stability has been modest at best. This view is stated in early studies by

Jaffee and Rosen (1978, 1979) and more recent studies by Frame and White (2005) and

Lehnert, Passmore, and Sherlund (2008). In contrast, Naranjo and Toevs (2002), a study

funded by Fannie Mae, found evidence of effective stabilization by the GSEs, as did

other studies carried out internally by the GSEs. Unlike the previous studies, Peek and

Wilcox (2003) focused on the flow of mortgage funds, and not on mortgage interest rates,

and found the GSE contribution to be countercyclical. Of course, this research was all

conducted before the subprime housing bubble and its collapse. In this event, as we now

document, the GSE participation was decidedly destabilizing.

A.4 The GSE Role in the Subprime Mortgage Boom and Crash

The losses reported by the GSEs starting in 2008 leave no doubt that the GSEs

acquired a significant volume of risky mortgages during the subprime boom. However,

16

the extent, timing, and significance of these acquisitions is debated. For example, Jaffee

(2010) describes the GSE role as “expanding” the subprime boom, especially in 2007,

whereas Wallison (2011, p.2) concludes that GSE activity, based on their housing goals,

was a primary “source” of the crisis. In this section, we evaluate the role played by the

GSEs in the subprime mortgage boom and crash.

A quantitative evaluation of the GSE role in the subprime crisis faces a number of

significant data issues:

1) Definitions for subprime and Alt A mortgages differ across data sets, and certain high-

risk mortgages are not included under either label.

2) Defining high-risk mortgages (including subprime and Alt A instruments) is

necessarily complex because mortgage default risk arises from numerous factors

including borrower and property attributes (FICO scores, loan-to-value ratios, etc.),

special amortization options (interest only, negative amortization, etc.), and fixed-rate

versus adjustable-rate loans.

3) The GSEs could not acquire any mortgages with an initial loan amount above the

conforming loan limit (so-called jumbo mortgages).

Our analysis starts by reviewing a newly compiled mortgage origination dataset

from the GSE regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (2010a).

10

These data

compare the risk characteristics of all mortgages acquired by the GSEs (whether

securitized or held in retained portfolios) with the risk characteristics of all conforming,

conventional, mortgages that were included in private label securitizations (PLS),

tabulated by year of mortgage origination. Because the dataset has nearly complete

coverage and is restricted to conforming mortgages, it provides the best available direct --

10

We thank Robin Seiler of the Federal Housing Finance Agency for providing us with a roadmap for the

intricacies of these data.

17

“apples to apples” -- comparison of the GSE acquired mortgages relative to the

comparable market. Nevertheless, there are two limitations. First, while the FHFA data

include all the conforming mortgages that collateralized PLS MBS instruments, the GSE

holdings of PLS tranches are not so identified. We do not expect a significant bias in the

comparisons from this source, however, because the GSE PLS holdings were almost

entirely AAA tranches with little ex ante credit risk.

11

Second, the FHFA data exclude

conforming mortgages that were not securitized (i.e., they were retained in lender

portfolios). To the extent that lenders did retain conforming mortgages with high-risk

attributes, the FHFA dataset will undercount the high-risk dimensions of the overall

conforming origination pools, and will therefore overstate the GSE share of all high-risk

originations. Here too, we do not expect a significant bias in our comparisons, because

most subprime and Alt-A mortgages were securitized, and the securitization rate was

even higher among those high-risk loans that were also conforming mortgages.

12

Panel A of Table 3 shows the dollar amount of the conforming mortgages by

origination year and various risk attributes. Rows (1) to (3) report on loans with one of

the identified high-risk factors: high loan-to-value (LTV) ratios, low FICO scores, and

adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) respectively. However, there is some double counting

11

See Thomas and Van Order (2011) for further discussion. PLS tranches as a share of total GSE

acquisitions reached its high point at 22.9 percent in 2005, but had fallen to 7.4 percent by 2007.

Furthermore, actual cash flow losses on GSE PLS positions have been modest to date, although the GSEs

have recognized significant mark to market valuation losses on these positions.

12

For example, 2007 data from Inside Mortgage Finance indicate that only $33 billion (or 7%) of the

subprime/Alt A mortgages originated that year were not securitized. Even if these were all conforming

mortgages, their share of total conforming originations that year would be less than 3 percent. Furthermore,

Inside Mortgage Finance indicates that over 31% of subprime MBS and 9 percent of Alt A MBS in 2007

were “GSE eligible”—i.e. conforming mortgages eligible for GSE purchase--further reducing the incentive

of portfolio lenders to hold these mortgages in unsecuritized form. It is also noteworthy that while there is

no consensus conclusion from the expanding literature on whether securitization created lax underwriting

standards—see for example the contrast between Bubb and Kaufman (2009) and Keys etal. (2010)—there

is no finding that portfolio lenders were systematically retaining high-risk mortgages.

18

since some loans have more than one of these attributes. The aggregate high-risk

originations shown in row (4) net out all double counting.

13

Row (6) shows the

percentage of high-risk mortgages as a share of total conforming mortgages (in row 5).

This high-risk share of total conforming originations rose steadily through 2004 and then

declined steadily thereafter.

Panel B of Table 3 computes the share of the conforming mortgages acquired by

the GSEs—whether as backing for guaranteed MBS or to hold on their balance sheets--

for each risk attribute. For example, in 2001, the GSEs acquired about 92.2 percent of all

conforming mortgages with LTV ratios above 90 percent. For all 3 of the risk attributes,

the GSE share fell steadily through 2005 and then expanded rapidly through 2007. By

2007, the GSEs were acquiring 79.9 percent of the high-risk, conforming, mortgage

originations. In interpreting these numbers, however, it must be recognized that, as shown

in row (11), the GSEs represent a large share of the overall conforming mortgage market;

as their overall market share approaches 100 percent, their share of each risk attribute

would necessarily do the same.

Panel C corrects for the large GSE share of the conforming market by computing

a “relative intensity,” dividing the GSE market share for each risk attribute in Panel B by

the overall GSE market share in Row (11). A coefficient of one indicates the GSEs are

holding the “market portfolio,” whereas coefficients below one indicate they are avoiding

risky mortgages and coefficients above one indicate the GSEs are actively acquiring risky

mortgages. The pattern for each of the three risk attributes shows the relative intensity

13

For example, for the fixed-rate mortgage originations in 2007, 2.2 percent had LTV > 90 percent and

FICO score < 620. For adjustable rate mortgages in 2007, 19.2 percent had either LTV > 90 percent or

FICO score < 620. Overall, in 2007 4.7 percent of the originated mortgages had more than one of the high-

risk attributes.

19

rising steadily starting in 2005. In each case, the high point of the seven-year history was

reached in 2007. Since the relative intensities over the full time span are generally less

than one, it would appear the GSEs were not leading the market for high-risk lending as

the subprime boom took off.

14

But the jumps in the relative intensities in 2007 for most of

the indicators suggest that the GSEs then rapidly expanded their participation in the

subprime boom. This is one key basis for our conclusion that the GSEs were a

destabilizing influence on the conforming mortgage market as the subprime boom headed

to its peak in 2007.

The analysis has so far focused on the GSE acquisition of high-risk mortgages as

a share of the overall conforming mortgage market. We now consider the GSE

acquisition of high risk mortgages as a share of their total acquisitions. Table 4 reports

the first three attributes high LTV ratios; low FICO scores; and ARMs; as reported in

Table 3. The time pattern is again distinctive, with the share of the GSEs new business

dedicated to mortgages with these high-risk attributes generally rising starting in 2004,

the only exception being the declining share of ARM acquisitions by Fannie Mae. The

companies also reported their acquisitions of interest-only, condo/coop, and investor

mortgages; and here too the pattern is generally rising from 2004. 2007 represents the

year of maximum share for each high-risk mortgage attribute with the exception of

Fannie Mae ARMs and Freddie Mac interest-only mortgages. These data thus present a

second independent basis for our conclusion that the GSEs were a decidedly destabilizing

influence on the conforming mortgage market as the subprime boom headed to its peak in

2007.

14

Thomas and Van Order (2011), although using different datasets, come to the same conclusion.

20

A.5 Mortgage Markets Without GSEs

The analysis above leaves little doubt that the GSEs destabilized the U.S.

mortgage market during the later stages of the subprime boom, but there is a further

question how the U.S. mortgage markets would function without the GSEs. To help

answer this, in this section we consider evidence from two sources: (1) how the U.S.

mortgage markets have performed without GSEs, and (2) the performance of the

mortgage markets in Western European countries.

The evidence that private mortgage markets have operated effectively in the U.S.

economy can be summarized with three comments on the historical role of private

markets within the U.S. mortgage market. First, private markets have always originated

100% of U.S. mortgages, and closing the GSEs would not affect this. Second, the GSEs

have never held a significant share of the outstanding U.S. home mortgages, this share

being, for example, 12 percent at year-end 2010. Third, the GSE MBS share of total

home mortgages first exceeded 30% only in 2007. This confirms that the private

markets—depository institutions and capital market investors--are capable of holding or

securitizing the large majority of U.S. mortgages. It is also noteworthy that the market for

jumbo mortgages—mortgages that exceed the conforming loan limit--has generally

functioned quite satisfactorily.

Turning to the European evidence, the European economies and housing markets

are sufficiently similar to the U.S. to provide a potentially interesting comparison, while

they have the key distinction that government intervention in these housing and mortgage

markets is far less than for the U.S.; in particular, none of these countries has entities with

21

any significant resemblance to the U.S. GSEs.

15

This conclusion is stated very clearly by

Coles and Hardt (2000, p. 778):

16

“There is no national or European government agency to help lenders fund

their loans. Mortgage loans have to be funded on the basis of the financial

strength of banks or the intrinsic quality of the securities. EU Law (Article

87 and 88 of the EC treaty) outlaws state aid in the form of guarantees as

there may be an element of competitive distortion.”

Table 5 compares the U.S. and Western European mortgage markets for a range

of quantitative attributes from 1998 to 2010 based on a comprehensive data base of

housing and mortgage data for fifteen European countries from the European Mortgage

Federation (2010). Column 1 compares the most recent owner occupancy rates for the

U.S. and European countries. The U.S. value is 66.9 percent, which is just below its peak

subprime boom value. It is frequently suggested that the high rate of homeownership is

the result of the large U.S. government support of the mortgage market, including the

GSEs. It is thus highly revealing that the U.S. rate is just at the median— eight of the

European countries have higher owner occupancy rates—and slightly below the average

value for the European countries. Furthermore, the lower owner occupancy rates in some

of the countries, Germany for example, appear to be the result of cultural preferences

rather than government inaction. A full analysis of the determinants of owner occupancy

rates across countries should also control for the age distribution of the population, since

younger households, and possibly the oldest households, may have lower ownership rates

in all countries. Chirui and Jappelli (2003) provide a start in this direction, showing that

lower downpayment rates are a significant factor encouraging owner occupancy after

15

See European Central Bank (2009) for an extensive review of housing finance in the European Union

countries.

16

Hardt was the Secretary General of the European Mortgage Federation at the time.

22

controlling for the population age structure in a sample of fourteen OCED countries. The

U.S. has also generally benefitted from very low downpayment rates, but it still has an

average ownership rate, reinforcing the conclusion that the government interventions

have been largely ineffective in raising the U.S. home ownership rate relative to its peers.

Column 2 measures the volatility of housing construction activity from 1998 to

2010 based on the coefficient of variation of housing starts as a measure of relative

volatility. The U.S. relative volatility is third highest out of the 16 countries, implying

that the government interventions have failed to reduce U.S. housing cycles relative to

those in Western Europe. Column 3 measures the volatility of house price changes based

on the standard deviation of the annual house price appreciation from 1998 through 2010.

Here the U.S. stands fifth, meaning the country has faced a relatively high rate of house

price volatility. This negative result is all the more significant because the U.S. is far

larger than any of the individual European countries, and thus the benefits of regional

diversification should have lowered the observed U.S. volatility.

Column 4 compares the level of mortgage interest rates in Western Europe and

the U.S., using “representative variable mortgage rates” for Europe and the Freddie Mac

one-year ARM commitment rate for the U.S. The column shows that the U.S. has the

sixth highest average mortgage interest rate from 1998 to 2010, and exceeds the Western

European average by 27 basis points. Since overall interest rates also vary across

countries, as a further test, column 5 shows the average spread between the mortgage rate

and the Treasury bill rate for each country. The U.S. ranks third highest based on the

spread and exceeds the Western European average by 70 basis points. Of course,

numerous factors determine these mortgage rates and spreads, including the precise terms

23

of the variable rate mortgages, other contract features such as downpayment

requirements, and the generally greater credit risk of U.S. mortgages. Nevertheless, the

fact remains that despite the government subsidies and other interventions in the U.S.

residential mortgage markets, U.S. mortgage rates have remained among the highest

levels compared with the countries of Western Europe. Finally, Column 6 shows the

20109 ratio of home mortgages outstanding to each country’s annual GDP, a standard

measure of the depth of a country’s mortgage market. The U.S. ratio is 75.5 percent

which puts it sixth within this group of sixteen developed economies. A relatively high

U.S. result would be expected, given the large mortgage subsidies provided through the

GSEs and other channels. It is noteworthy, therefore, that five Western European

countries achieved even higher ratios without substantial government interventions in

their mortgage markets

The overall conclusion has to be that Western European mortgage and housing

markets have outperformed the U.S. markets over the full range of available measures.

Although data are not provided here, a similar conclusion would hold for the Australian

and Canadian mortgage markets; see Lea (2010). There are, of course, a wide range of

possible explanations for the superior performance of the European mortgage markets.

The key point for present purposes is simply that the superior performance of the

European mortgage markets is not explained by greater government intervention. In the

absence of GSEs, almost all Western European mortgage lending is carried out privately

by banks, primarily funded by bank deposits or covered bonds. Other indirect forms of

government support, such as the tax deductibility of mortgage interest and property taxes

are also notably absent in most European countries.

24

B. Other Justifications for GSE Subsidies

The activities of the GSEs are justified by the particular benefits accruing to

specific classes of borrowers, or more specifically, to all home purchasers and

homeowners from the activities supported by these institutions. As noted above, benefits

have been claimed for the stabilization of the mortgage supply and corresponding

reductions in the volatility of housing construction and home sales. But there are at least

three other classes of potential benefits arising from the GSE:

Increases in the extent of mortgage credit accruing to income and demographic

groups that policy-makers appear to have deemed particularly deserving -- credit which

augments that supplied by the private marketplace;

Increases in the lending support provided to builders, owners, or residents of

specific types of housing, e.g., multifamily rental housing, which would otherwise not be

provided in the market;

Subsidies accruing more broadly to housing market participants, for example, to

all home purchasers in the form of lower interest costs arising from the increased

liquidity afforded by the GSEs and the implicit guarantee of repayment provided by those

institutions;

This section reviews the evidence on the extent and distribution of these benefits.

1. Increased Credit to Targeted Groups and Geographical Areas

The original charter establishing Fannie Mae as a GSE in 1968 recognized a

“national goal of providing adequate housing for low and moderate income households,”

and it authorized the Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD) to require that a reasonable portion of Fannie Mae’s purchases of home

25

mortgages be related to this goal. Although regulations requiring the GSEs to allocate a

fixed percentage of mortgage purchases to lower-income households were advanced in

the 1970s, mandatory rules were not proposed in Congress until after the passage of the

Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) of 1989.

Ultimately, the Federal Housing Enterprises Financial Safety and Soundness Act of 1992

modified and made more explicit the “housing goals” to be promoted by the GSEs. The

Act directed the HUD Secretary to establish quantitative goals for mortgages to “low-

and moderate-income” households and for mortgages originated in “underserved areas.”

It also imposed a “special affordable housing goal” for mortgages for low-income

housing in low-income areas. The 1992 legislation stipulated two-year transition goals,

but after that period, the HUD Secretary was empowered to promulgate more detailed

regulations.

Under the HUD regulations, finalized in December 1995, the first goal (“low- and

moderate-income housing”) directs that a specified fraction of new loans purchased each

year by the GSEs be originated by households with incomes below the area median. The

second goal (“underserved areas”) requires that a specified fraction of mortgages be

originated in census tracts with median incomes less than 90 percent of the area median,

or else in census tracts with a minority population of at least 30 percent and with a tract

median income of less than 120 percent of area median income. The third goal (“special

affordable housing”) targets mortgages originated in tracts with family incomes less than

60 percent of the area median; or else mortgages in tracts with incomes less than 80

percent of area median and also located in specific low-income areas. Any single

mortgage can “count” towards more than one of these goals. (For example, any loan that

26

meets the “special affordable housing” goal also counts towards the “low- and moderate-

income” goal.)

The numerical goals originally set by HUD for 1996 were modest – requiring, for

example, that 40 percent of the GSEs’ mortgage purchases be loans made to households

with incomes below the area median. Over time, the goals for new business set by HUD

have been increased.

17

The goal for mortgages to low- and moderate-income households

has been increased from 40 percent in 1996 to 56 percent by 2008. Until 2007, mortgage

originations by both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had reached their primary goals every

year. The HUD goal for “underserved areas” was increased from 21 percent in 1996 to 39

percent in 2008. Originations by the larger GSE, Fannie Mae, exceeded this goal in every

year; originations by Freddie Mac exceeded the goal in each year until 2008. The “special

affordable” housing goal was increased by HUD from 12 percent in 1996 to 27 percent in

2008. Both GSEs surpassed this goal in loan originations each year until 2008.

Figures 5, 6, and 7 report the HUD goals and GSE progress in achieving those

goals from their publication in 1995 to the federal takeover of the GSEs in 2008.

Figures 8, 9, and 10 provide another perspective on the magnitude of the goals set

by HUD for the GSEs. They report each of the three goals as well as an estimate of the

share of all newly-issued mortgages in each of the categories. For example, in 2000 the

HUD-specified “low- and moderate-income goal” was to reach 42 percent of new

purchases for the GSEs. However, in 2000 low- and moderate-income mortgages,

according to the same definition, constituted about 59 percent of all new mortgages. At

17

Note, however, that at the time that the 1992 act was debated in Congress, only 36 percent of Fannie

Mae’s single-family deliveries were for housing whose value was below the area median. (See FHFA

Mortgage Market Note, The Housing Goals of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, February 1, 2010.)

27

that time, the “underserved areas” goal was 21 percent of GSE mortgages, while these

mortgages constituted more than a 30 percent market share of new mortgages. In virtually

all cases, the goals imposed were a good bit lower than the share of mortgage loans of

that type originated in the economy. There is no evidence that the goals were set so that

the GSEs would “lead the market” in servicing these groups of households.

2. Increased Credit to Targeted Housing Types: Multifamily

Numerical goals for purchases of multifamily mortgages are not mentioned in the

Financial Safety and Soundness Act of 1992, but there was considerable concern at the

time that the GSEs were not financing their “fair share” of multifamily housing,

especially small multifamily properties. For example, in 1991, small multifamily units

accounted for less than five percent of Freddie Mac’s multifamily unit purchases. At that

time, small multifamily units constituted 39 percent of all recently-financed multifamily

units. (See Herbert, 2001.) Thus, the first rules for implementing the 1992 Act put

forward by HUD also included explicit goals for multifamily housing.

These goals have been in the form of dollar-based targets. Goals in 1996-2000

were approximately 0.8 percent of the mortgage purchases of Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac recorded in 1994; goals in 2001-2004 (2005-2007) were 1.0 percent of each GSE’s

estimated mortgage purchases in 1997-1999 (2000-2002). Beyond the achievement of

these numerical goals, multifamily mortgage purchases also qualified for “bonus points”

towards the achievement of the three goals specified in the 1992 law. It has been argued

that these “bonus points” (discontinued in 2004) were a major inducement leading to an

increase in participation by the GSEs in the multifamily housing market, particularly in

their financing of small multifamily properties. (See Manchester, 2007.)

28

Figure 11 reports the dollar goals for multifamily dwellings specified by HUD

regulations and the performance of each of the GSEs. As noted in the figure, until quite

recently purchases of multifamily dwellings exceeded the HUD goal by a substantial

amount.

V. Broad Benefits to Homeowners and Purchasers

a. The Effectiveness of the GSE Goals in Directing Mortgage Credit

Of course, the finding that the GSEs have achieved the annual goals specified in

regulations need not imply that Freddie and Fannie have been very effective in increasing

mortgage credit to targeted groups. For example, many suggest that the numerical goals

set for the GSEs have been far too low (e.g., Weicher, 2010), and that, as a result the

GSEs have simply followed the market with a lag of a few years. Indeed, the data in

Figures 5, 6 and 7, provide no evidence that Freddie Mac or Fannie Mae purchased more

than their “fair share” of mortgages in any of these areas of congressional concern. GSE

purchases of mortgages that satisfied any of these congressional goals – as a fraction of

all new purchases – were consistently smaller than their “market share” in all newly-

issued mortgages.

Similarly, Figure 11 indicates that the GSEs’ new purchases of “special

multifamily” mortgages greatly exceeded the dollar goals mandated by HUD in every

year.

Finally, Figure 12 demonstrates that the GSEs’ multifamily housing business was

only a small fraction of the mortgage purchases of the GSEs in any year. It never

amounted to even seven percent of either GSEs’ purchases.

29

Figure 13 reports the aggregate amount of commercial mortgage backed security

(CMBS) and multifamily originations between 2003 and 2009 as reported by the

Mortgage Bankers of America. Mortgage originations by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae

were small – less than $9 billion in any year. Until 2008, GSE originations were less than

twenty percent of all such mortgage banker mortgage originations. Note, however that in

2008-2009, CMBS and commercial banks left the market entirely; originations by life

insurers declined as well. Since the conservatorship in 2008, virtually all multifamily

mortgages have been originated by the GSEs.

These simple comparisons suggest that any causal effect of the GSEs on lending

to specific income classes, neighborhoods, and property types is not likely to be large –at

least before 2008. Economic analysis of the potential impacts of the GSEs is also

complicated by other public programs in effect. For example, in 1977, the Community

Reinvestment Act (CRA) was passed to encourage banks to exert further efforts to meet

the credit needs of their local communities, including lower-income areas. In identifying

neighborhoods of special concern in administering the CRA, neighborhoods (census

tracts) with median incomes below 80 percent of the area median income are targeted. As

noted above, “underserved areas” of concern in GSE regulation are census tracts with

median incomes below 90 percent of the area median income. In addition, many

borrowers targeted under GSE criteria are also eligible for Federal Housing

Administration (FHA) loans or Veterans’ Administration (subsidized) loans.

The existence of parallel government programs under the CRA, FHA, and VA

raises the possibility that the GSE purchases of qualifying mortgages simply displaced

lenders who would have made the same mortgage under one of the other programs. To

30

the extent that this has been the case, the GSE purchases would have had no noticeable

impact on the mortgage market for the qualifying borrowers. Of course, it is a subtle

empirical problem to determine whether the GSE purchases were simply displacing loans

from the other programs. Nevertheless, a number of academic papers have sought to

identify and quantify the effects of the GSE goals on local and neighborhood housing

markets and on classes of borrowers.

Table 6 summarizes much of this research.

An early paper by Canner, Passmore and Surette (1996) examined loans eligible

for insurance under the FHA. The authors evaluated how the risk associated with these

loans is distributed among government mortgage institutions, private mortgage insurers,

the GSEs, and banks’ in-house portfolios. The results indicated that FHA bears the

largest risk share associated with lending to lower-income and minority populations, with

the GSEs lagging far behind. Bostic and Gabriel (2006) analyzed the effects of the GSE

mortgage purchase goals upon homeownership and housing conditions in California. A

careful comparison of neighborhoods just above the GSE cutoff for “low-moderate-

income” and “special affordable” designation with nearby neighborhoods just below the

cutoff found essentially no differences in the levels and differences in home-ownership

rates and housing conditions during the decade of the 1990s.

In a more sophisticated analysis using a similar comparison of neighborhoods

“just above” and “just below” the GSE cutoff, An, et al, (2007) focused on three

indicators of local housing markets: the home ownership rate, the vacancy rate, and the

median home value. The authors related (an instrument for) the intensity of GSE activity

in a census tract to these outcomes, using a variety of control variables. The results

31

indicated that increases in GSE purchase intensity were associated with significant but

very small declines in neighborhood vacancy rates and increases in median house values.

The authors conclude that the “results do not indicate much efficacy of the GSE

affordable housing loan-purchase targets in improving housing market conditions (2007,

p. 235).”

Two papers by Bhutta (2009b, 2010) adopted a regression discontinuity design to

test the effects of the “underserved areas” goal upon the supply of credit to those areas.

Rather than attempt to match similar neighborhoods for statistical analysis, Bhutta

exploited the facts that census tracts qualified for CRA scrutiny if their median incomes

were 80 percent of the local area, and they qualified for scrutiny under the HUD GSE

goals if their median incomes were 90 percent of the area median design. Bhutta merged

tract-level data on mortgages (from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act) with

neighborhood (census) data. Bhutta’s results (2009a) do find a significant effect of the

“underserved area” goal on GSE purchasing activity – but the effect is very small (2-3

percent during the 1997-2002 period).

A more recent paper by Moulton (2010), also using a regression discontinuity

approach, finds no effect of the GSEs -- on individual loans rather than aggregate credit

allocations. Moulton uses micro data on mortgage loan applications to examine whether

the GSE’s affordable housing goals altered the probability that a loan application was

originated by a mortgage lending institution or that a loan was purchased by one of the

GSEs. The analysis led to the conclusion that the GSE affordable housing goal had no

effect at all on mortgage lending or on GSE purchases.

32

The consistent finding of little or no effect of the GSE goals on housing

outcomes, mortgage applications, or mortgage finance could suggest that there is little

effect of the GSE rules upon FHA lending as well. But several papers have reported that

an increased market share of GSE mortgages in a census tract is associated with a decline

in the FHA share of mortgages (An and Bostic, 2008; Gabriel and Rosenthal, 2010).

These results may explain why the increases in lending mandated by the HUD

regulations to achieve the congressional goals of the 1992 Act have had very little net

impact on housing and neighborhood outcomes. Small increases in GSE activity have

been offset by roughly comparable declines in FHA activity.

The extent to which an expansion of GSE activity simply crowds out private

mortgage purchases remains an open research question. For example, Gabriel and

Rosenthal (2010) argue that increased GSE activity in the mortgage market involved little

or no crowd-out until about 2005. After that, GSE activity crowded out private activity

until the crash in mortgage markets in 2007.

But even if there were a complete crowd-out of private mortgage activity arising

from GSE behavior , it is hard to attribute any of this to the goals set by the 1992 Act –

especially since the goals were substantially less than the share of these new mortgages in

the market.

To summarize: the academic and scientific literature has generally found little

effect from housing goals as they operated through the GSEs. The goals were low.

Despite appearances, they provided no incentive for the GSEs to “lead the market” in

providing credit to potentially riskier housing investments. They accomplished nothing in

increasing credit for riskier loans.

33

But there is a view that the housing goals were actively harmful in facilitating the

subprime housing crisis.

This position has been put most forcefully by Peter Wallison (2011) in his rebuttal

statement to the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. He argues that the requirement to

meet the housing goals “forced” the GSEs to make substandard loans, which is why they

ultimately acquired such large positions in subprime mortgages and subprime mortgage

securities. Indeed, Wallison claims that the HUD goals actually “caused” the subprime

crisis. There is no question that the GSEs ultimately acquired large portfolios of subprime

mortgages and securities -- see our discussion in Section IV.A.4 above -- but Wallison

provides no evidence at all that these subprime portfolios had anything to do with the

GSE goals.

However, an impressive journalistic account of recent history in the mortgage

market argues forcefully that the housing goals in the 1992 act led directly to the

subprime mortgage debacle of 2008 (Morgenson and Rossner, 2011). Our analysis of the

academic literature supports no such claim. It is certainly possible that the passionate

rhetoric from the GSEs provided a convenient “cover” for the trend towards lower

quality, even toxic, mortgages by 2004-2005. However, there is no evidence that this

rhetoric increased GSE lending to targeted groups during the 1990s. Ironically (or

perhaps diabolically), the rhetoric about “affordable housing” from the GSEs had little

effect upon their own mortgage purchases until the subprime crisis was well underway.

As noted above, the empirical evidence simply fails to support a claim that the

GSE housing goals were a primary source of the subprime crisis. First, there are simple

questions of timing. The GSE goals were enunciated in a law passed in 1992; it is

34

implausible that their effect was not felt until a quarter century had elapsed. Further, as

noted below, the GSE accumulation of subprime mortgages accelerated only in 2007, too

late to have “caused’ the subprime bubble (but certainly early enough to have accelerated

it).

Second, as noted above, it appears that the GSE mortgage purchases in support of

the housing goals were principally loans that would otherwise have been made by other

lenders.

Most importantly, the subprime crisis has a long list of proximate causes,

including U.S. monetary policy, a global savings glut, the error of assuming a national

housing pricing collapse was highly unlikely, etc. (see Jaffee, 2009 for further

discussion.)

b. Benefits to all housing market participants

There has been active research seeking to establish the value of the enhanced

liquidity and subsidy to homeowners. In principle, the subsidy provided by the implicit

guarantee can be calculated. Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae issue debt in the same market

as other participants in the banking and finance industry participate. The yield difference

(“spread”) between the debt of the GSEs and that of other firms can be applied to the

newly issued GSE debt to compute the funding advantage in any year arising from the

GSE status. Of course, it is not quite straightforward to apply this principle and to

produce credible estimates. The relevant benchmark estimate (i.e., the appropriate sector

and bond rating) is not without controversy, and a comparison with broad aggregate

indices combines bonds containing a variety of embedded options. Pearce and Miller

(2001), among others, reported comparisons of GSE and AA-rated financial firms,

35

suggesting that the agencies enjoyed a 37 basis point (bps) spread. More sophisticated

comparisons by Nothaft, et al, (2002) suggest that the relative spreads are about 27 bps

(vis-à-vis AA-minus firms). Table 7 summarizes available comparisons. A careful

analysis of yields at issue for GSE debt and the option-free debt issued by a selection of

finance industry corporations (Ambrose and Warga, 2002) concludes that the GSEs enjoy

a spread of 25-29 bps over AA bank bonds and 37-46 over AA financials. Quigley (2006)

provides a terse summary of available estimates.

18

The substantial subsidies arising from the funding advantage of the GSEs means

that mortgage rates for all homeowners can be lower than they otherwise would be, that

is, the subsidy can improve the well-being of homeowners and home purchasers.

But of course, in the first instance the subsidy is provided directly to private

profit-making firms with fiduciary duties to their shareholders. It is thus not obvious that

all, or even most, of the funding advantage provided by the public subsidy is passed

through to homeowners. As documented by Hermalin and Jaffee (1996), the secondary

market for mortgage securities (at least for those securities composed of loans

comparable to the rules under which Fannie and Freddie operate) is hardly a textbook

model of atomistic competition. The two GSEs are large, and each has a large market

share of the conforming segment of the market. There are high barriers to entry, and the

MBS product is more-or-less homogeneous. Moreover, mortgage originators have an

inherent first-mover advantage in deciding which newly-issued mortgages to sell to

Fannie and Freddie. This may force the GSEs to pay a premium for the mortgages they

18

These estimates are in the range of the spreads which have been assumed (41 bps) by the Congressional

Budget Office (CBO, 2001) in estimating the annual federal subsidy to the GSEs. They are similar to the

estimates of spreads (40 bps) used by Passmore, (2005) in a more recent exercise.

36

purchase in the market. These factors, duopoly and adverse selection, may mean that

much of the subsidy accrues to the shareholders of the GSEs or to the owners of other

financial institutions, not to homeowners or home purchasers.

The effects of the GSEs upon mortgage rates can be calculated by estimating the

spread between the interest rates on mortgages which conform to the loan limits and

underwriting guidelines of the GSEs and the rates on otherwise comparable mortgages.

As in the analysis of funding advantages, it is not quite straightforward to apply this

principle and to produce credible estimates. (For example, most research compares the

rates paid by borrowers with loans one dollar below the conforming limit with rates paid

by borrowers with loans one dollar above the limit. But the latter group of borrowers

differs from the former group, or else they surely would have made an additional cash

payment and taken a conforming loan.)

19

Early analyses, e.g. by Hendershott and Shilling (1989) comparing interest rates

on jumbo and conforming mortgages, indicated that this spread was 24-39 bps. More

recent studies, e.g., by Passmore, et al (2002), by McKenzie (2002), and by the CBO

(2001), conclude that the spread is 18-23 bps. These more recent studies differ mostly in

their application of more complex screens to insure comparable data for conforming and

nonconforming loans. Table 8 summarizes these comparisons. More recent work by

Passmore, et al (2005) suggests that this spread may be as low as 16 bps.

19

Of course, other reasons besides the greater liquidity provided by the GSEs could explain some of an

observed spread between jumbo and conforming mortgages. Jumbo mortgages are generally prepaid more

aggressively -- borrowers have more at stake, if nothing else. This means that investors will require higher

rates on jumbos merely to compensate for the increased prepayment risk. On the other hand, borrowers

with jumbo mortgages have better credit, and they make larger down payments, which should create lower

rates on jumbo mortgages. See, also, Ambrose, et al (2001), Heuson, et al (2001), or Woodward (2004b).

37

In summary, it appears that the GSEs’ funding advantage is about 30-40 bps, and

the effect of this is to reduce mortgage rates by 16-25 bps. Stated another way, on the

order of half of the subsidy rate to the GSEs is transmitted to homeowners in the form of

reduced mortgage interest rates. Presumably, the remainder is transmitted to the

managers of the GSEs, the shareholders of the enterprises or to the owners of other

financial institutions.

20

VI. Where Do We Go From Here?

As noted in the introduction, most commentators agree that the current structure

of the housing finance system must be reformed in the very near term. A question of first-

order importance is then the likely consequences of the role of government in support of

the U.S. housing and mortgage markets, whether as a modification or replacement of the

GSEs.

The research results reported in this paper make it clear, we think, that the public

benefits arising from the GSEs have been quite small. The establishment of Fannie Mae,

a half century ago, and the establishment of Freddie Mac, forty years ago, did stimulate a

more stable national market for housing finance and did substantially improve the

liquidity and access of the market. As reported above, however, the specific benefits

arising from the GSE structure have been minor. In any event, these benefits -- with some

contributions from the GSEs -- were achieved by the 1980s. There now exists a national

market for home mortgages. The GSEs have followed reform in the secondary market

and have benefited from private innovation.

20

Of course, the net effects of the GSEs upon public welfare and the economy has greatly exceed the three

effects upon housing market participants discussed here. Indeed, the evidence suggests that the macro

economic effects of the structure and operation of the GSEs during the past half decade has been much

more important for the economy than the direct housing-market effects of the institutions.

38

There have been surprisingly few benefits to deserving households or

neighborhoods which can be attributed to the GSEs. There has been more political or

partisan attention to the cause of homeownership among lower-income households as a

result of powerful advocacy by the interests of GSEs, but there is little evidence that

lower-income homeownership was stimulated at all, at least not until the run up to the

housing bubble.

It is true that the GSE structure has reduced interest rates on home mortgages, by

about a quarter percent or so. But this benefit to homeowners has arisen from the federal

guarantee for GSE debt. And the public cost of the subsidy has been far more than the

benefits of lower interest rates to homeowners. About half of the overall subsidy has

accrued to GSE employees, shareholders, and other market intermediaries. These large

losses are directly attributable to the GSE structure which was created in 1968.

As noted below, we also conclude that the structure of the GSEs themselves has

made regulation of the housing market far less transparent and has extended some of the

consequences of the housing bubble of the past half decade.

A. The Appropriate Role for Government in the U.S. Residential Mortgage

Market

If the GSEs in current form are to be closed, the fundamental policy question is to

decide which government interventions, if any, should replace GSE functions and which

should be performed by the private sector? Once that is decided, there is also the delicate

issue of how to manage the transition from the current GSE conservatorship. Fortunately,

there are two quite flexible instruments available to close down the GSEs in a smooth,

safe and dependable manner: (i) steadily reduce the conforming loan limit until it reaches

39

zero; and (ii) steadily raise the fee charged by the GSEs for guaranteeing MBS. Although

we will return to questions of the dynamic transition below, the key question is to

determine the appropriate role of government in the U.S. mortgage market.

A large number of proposals have been offered for the reform of the U.S.

mortgage market, ranging from a mortgage market managed primarily by private sector

entities to recreation of the GSEs as public/private hybrids (albeit with new controls).

Summaries and analyses of the general approaches are available in U.S. General

Accountability Office (2009), Congressional Budget Office (2010), and Bernanke (2008).

The following is an annotated list of the three primary proposals scrutinized:

Reestablish GSEs with tighter controls and explicit guarantees. The entities would

continue their organization as public/private hybrids, but with tight government

controls, sometimes described as a “public utility” model. In most plans, the

government guarantees would apply to the underlying mortgages, not the newly

created entities. A cooperative structure such as that of the current Federal Home

Loan Banks is an alternative version. The number of entities to be chartered varies by

proposal.

Restructure GSE functions explicitly within a government agency

. A simple version

would create a government agency that would explicitly insure mortgages up to some