Mortgage-Backed

Securities

Andreas Fuster | David Lucca | James Vickery

NO. 1001

FEBRUARY 2022

Mortgage-Backed Securities

Andreas Fuster, David Lucca, and James Vickery

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 1001

February 2022

JEL classification: G10, G12, G21

Abstract

This paper reviews the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market, with a particular emphasis on agency

residential MBS in the United States. We discuss the institutional environment, security design, MBS

risks and asset pricing, and the economic effects of mortgage securitization. We also assemble descriptive

statistics about market size, growth, security characteristics, prepayment, and trading activity.

Throughout, we highlight insights from the expanding body of academic research on the MBS market

and mortgage securitization.

Key words: mortgage finance, securitization, agency mortgage-backed securities, TBA, option-adjusted

spreads, covered bonds

_________________

Lucca: Federal Reserve Bank of New York (email: [email protected]g). Fuster: Ecole Polytechnique

Fédérale de Lausanne, Swiss Finance Institute, and CEPR (email: and[email protected]). Vickery:

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (email: james.vickery@phil.frb.org). This is a preliminary draft of

a chapter to be published in the Research Handbook on Financial Markets, edited by Refet Gürkaynak

and Jonathan Wright. The authors thank the editors, discussant Benson Durham, and Eric Horton, You

Suk Kim, Haoyang Liu, Dean Parker, Shane Sherlund, and Andreas Strzodka for helpful comments and

suggestions. Natalie Newton provided outstanding research assistance.

This paper presents preliminary findings and is being distributed to economists and other interested

readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of

the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Banks of New York and

Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the

author(s).

To view the authors’ disclosure statements, visit

https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr1001.html.

1 Introduction

The mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market emerged as a way to decouple mortgage

lending from mortgage investing. Until the 1980s, nearly all US mortgages were held on

balance sheet by financial intermediaries, predominately savings and loans. Securitiza-

tion today allows these mortgages to be held and traded by investors all over the world,

and the US MBS market is one of the largest and most liquid global fixed-income markets,

with more than $11 trillion of securities outstanding and nearly $300 billion in average

daily trading volume.

1

MBS and a related instrument, covered bonds, are also used for

funding mortgages in many European countries as well as some other parts of the world.

This paper presents an overview of the MBS market, including the institutional envi-

ronment, security design, MBS risks and asset pricing, and the economic effects of mort-

gage securitization. It also assembles descriptive statistics about the MBS market, includ-

ing market size, growth, security characteristics, prepayment, trading activity and yield

spreads. We particularly focus on the large agency residential MBS market in the United

States, but also discuss other types of MBS both in the US and around the world. We also

consider the role of the Federal Reserve through its quantitative easing program.

Throughout, we highlight insights from the growing literature on MBS and mortgage

securitization, a body of research catalyzed by the role of MBS markets in the 2008 finan-

cial crisis. We also highlight topics for future research. This paper can only scratch the

surface of such a complex topic, however, and for other surveys and further information,

we refer the reader to Hayre (2001), McConnell and Buser (2011), Green (2013), Davidson

and Levin (2014), Fabozzi (2016) and Kim et al. (2022).

2 The MBS universe

2.1 MBS market segments and their evolution over time

Mortgage-backed securities are bonds with cash flows tied to the principal and interest

payments on a pool of underlying mortgages. Mortgage securitization has a long history

(e.g., see Goetzmann and Newman, 2010), but the birth of the modern US MBS market is

typically dated to the issuance of the first agency MBS pool by Ginnie Mae in 1970.

1

Source: SIFMA. Includes commercial and residential MBS pools and collateralized mortgage obligations.

1

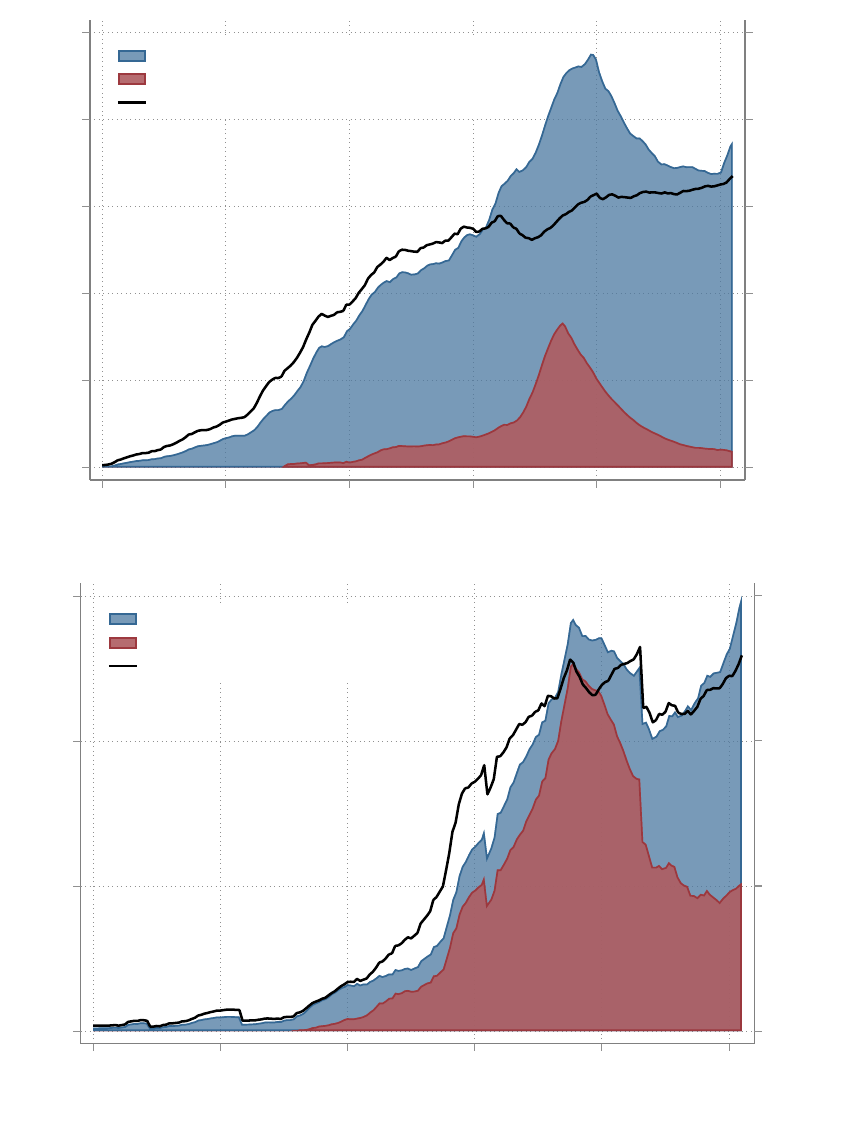

Figure 1 documents the enormous growth in the MBS market over the past half-

century. The figure breaks down the market along two key dimensions:

• Agency vs nonagency. Agency MBS carry a government-backed credit guaran-

tee from one of three housing agencies: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or Ginnie Mae.

2

Nonagency MBS, on the other hand, are issued by private financial institutions and

are not guaranteed. Instead, securities are tranched in terms of seniority to cater to

investors with different credit risk appetites.

• Residential vs commercial. The bulk of MBS are backed by mortgages on indi-

vidual residential properties (RMBS). But there is also an active commercial MBS

(CMBS) market secured by a diverse range of commercial real estate (e.g., office,

multifamily, industrial, hotel, and warehouse properties). Commercial mortgages

are larger, more complex and more heterogenous than residential mortgages, and

these features are reflected in the design of CMBS, as we discuss in section 3.

The top panel of Figure 1 plots the evolution of the volume of residential MBS. The

market began to expand significantly in the early 1980s, driven at the time by high and

volatile interest rates and the need to alleviate the maturity and liquidity mismatch faced

by savings and loans. Regulatory and tax incentives also played an important role.

3

The

RMBS market continued to expand rapidly over the following two decades, with the

volume of securities outstanding reaching almost 50% of GDP by the time of the Great

Recession. Particularly notable is the rapid growth in nonagency MBS during the 2000s

due to the issuance of subprime and “alt-A” MBS backed by mortgages with high levels

of credit risk.

4

2

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac purchase and securitize “conforming” mortgages, which are typically

prime-quality loans. They are not permitted to purchase large jumbo mortgages above the conforming

loan limits or mortgages with a loan-to-value (LTV) ratio exceeding 80 percent unless the loan carries

mortgage insurance. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are “government-sponsored enterprises” or GSEs.

Although not explicitly government-owned, their debt is perceived to carry an implicit public guarantee,

and the two GSEs have been in public conservatorship since 2008 (Frame et al., 2015). Ginnie Mae

guarantees MBS assembled from mortgages explicitly insured by Federal government agencies, primarily

the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Veterans Affairs (VA). See Burgess et al. (2022) for more

details on these agencies.

3

See the finance classic Liar’s Poker (Lewis, 2010) for a lively account of the MBS market during this period.

4

This included loans to borrowers with low credit scores, interest-only and negative amortization

mortgages, and loans with incomplete documentation of borrower income and assets. The growth and

collapse of the nonagency mortgage market during the 2000s is of course the subject of a very large

literature. See, e.g., Gerardi et al. (2008), Ashcraft and Schuermann (2008), Mian and Sufi (2015), Adelino

et al. (2016), Foote et al. (2020), Adelino et al. (2020) and references cited therein.

2

The housing crash and wave of mortgage defaults that precipitated the Great Reces-

sion also caused a freeze in the issuance of nonagency MBS in mid-2007 (Calem et al.,

2013; Vickery and Wright, 2013; Fuster and Vickery, 2015; Kruger, 2018). The market has

partially recovered but nonagency MBS issuance remains far below pre-crisis levels even

to the present day. The MBS market as a whole remains very active, however — as of

2021, 65% of total home mortgage debt is securitized into MBS, up from 60% a decade

ago, nearly all of it in the form of agency MBS. The stock of MBS as a percent of nom-

inal GDP is smaller than prior to the Great Recession though, reflecting the post-crisis

normalization of household leverage.

The bottom panel of Figure 1 focuses on CMBS. The CMBS market is smaller than the

residential market, and did not grow in earnest until the 1990s, fueled by the Resolution

Trust Corporation which issued securities backed by distressed commercial real estate in

the wake of the savings and loan crisis (An et al., 2009; Chandan, 2012). Like its residen-

tial cousin, the nonagency CMBS market experienced an extraordinary boom during the

2000s — almost tripling in size as a percentage of GDP — before CMBS issuance ground

to a halt at the start of the Great Recession. The market has returned to health in the post-

crisis period, but normalized by GDP, the volume of nonagency CMBS today is only at

the level of the early 2000s.

In contrast, the agency CMBS market has grown rapidly since the Great Recession.

These securities have an explicit or implicit government credit guarantee, like agency

RMBS, and are typically backed by mortgages on apartment buildings or other form of

multifamily housing (e.g., senior housing, student housing).

5

Competition and substitution between government-backed and private securitization

is a central feature of both the commercial and residential market. For instance, Adelino

et al. (2020) show that high-LTV lending migrated almost entirely from the FHA and

VA to the private subprime market during the 2000s boom, before shifting back during

and after the Great Recession. The market price of credit risk is a key driver of these

substitution effects, because credit guarantee fees on agency MBS are set administratively

and do not reflect market prices. For example, in recent years the rise in the guarantee

fees charged by the GSEs has driven some lending from the agency to nonagency market

and has also induced banks to retain low-risk mortgages on balance sheet rather than

5

See Credit Suisse (2011) for a primer on the agency CMBS market.

3

securitizing them.

Regulatory policies also shape the relative size of the agency and nonagency market

and likely contributed to the slow post-crisis recovery of nonagency RMBS, including:

(i) the introduction of higher conforming loan limits in counties with high home prices,

which expanded the footprint of the GSEs (Vickery and Wright, 2013); (ii) Dodd-Frank Act

risk retention requirements and constraints on household leverage through the “Ability-

to-Repay” (ATR) rule (DeFusco et al., 2019)

6

; and (iii) bank liquidity regulations that favor

agency securities (Roberts et al., 2018).

2.2 Investors

Who invests in MBS? The Financial Accounts of the United States provides a partial

answer by tabulating investors in agency and GSE-issued securities, a category which

mainly comprises agency MBS. As of mid-2021, depository institutions are the largest

class of investors (32% of the total), followed by the Federal Reserve (23%), international

investors (11%), mutual funds (7%) and money market funds (5%). A full tabulation is

provided in the Appendix.

More details on bank MBS holdings are presented in Federal Reserve Bank of New

York (2021). Banks invest very heavily in agency MBS, which account for about half of

banks’ total investment security holdings. Banks are also significant investors in agency

collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), and to a lesser extent, nonagency MBS.

The Federal Reserve is the single largest agency MBS investor through its large-scale

asset purchase program, with total holdings of $2.5 trillion as of October 2021. Research

has found that Fed MBS purchases reduce MBS yields and have a range of other effects

on financial markets and the macroeconomy (see section 4).

6

The Dodd-Frank ATR rule requires lenders to ensure the borrower can repay the loan before extending

credit. Lenders can satisfy the ATR requirement by originating “qualified mortgagages” (QMs) that satisfy

particular criteria (these criteria have recently changed, but previously a key restriction was that the the

debt-to-income ratio could not exceed 43 percent). But a rule known as the “QM patch” designated all

mortgages sold to the GSEs as qualified mortgages, regardless of their characteristics. The ATR rule

combined with this GSE carve-out likely constrained the volume of risky mortgages securitized through

the nonagency market. The QM patch expired in 2021.

4

2.3 Agency RMBS in the cross-section

Table 1 provides a cross-sectional snapshot of the population of agency residential MBS

pools based on security-level data from eMBS as of March 2021. We divide the universe

by agency—Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or Ginnie Mae. Within the Ginnie Mae population,

we separately break out multi-issuer pools, because they are much larger and more di-

versified than other Ginnie Mae pools and make up the bulk of new Ginnie issuance (see

also section 3). Averages and distributional statistics reported in the table are weighted

by outstanding pool balance.

The population consists of just over a million individual MBS pools, which together

comprise $7.7 trillion of home mortgage debt. Almost all of this debt consists of fixed-

rate mortgages (FRMs), mainly in the form of 30-year FRMs ($6.5 trillion of the total). For

Fannie, Freddie, and Ginnie multi-issuer pools, around 95% of the pool balances are de-

liverable in the “to-be-announced” (TBA) market, which is the primary venue for agency

MBS trading (see section 5).

Strikingly, 42% of the outstanding balance reflects pools with an age of one year or

less.

7

This is an unusually high percentage, due to a record refinancing wave and home

price boom in 2020 that resulted in around $4 trillion of mortgage originations (Fuster

et al., 2021). Even so, nearly a quarter of the total unpaid balance comprises pools with

an age exceeding 5 years. This diversity of vintages is also evident in the distribution of

coupons (the rate of interest paid to investors). About 45% of the universe consists of MBS

pools with a coupon of 2.5% or lower — these are the typical coupons into which new

mortgages would be securitized, reflecting recent record-low mortgage rates. But there

is still a substantial population of much higher coupons, with 18% of the total unpaid

balance reflecting coupons of 4% or higher. Borrowers represented in these pools would

almost surely benefit substantially from refinancing, but for one reason or another have

failed to do so (see, e.g., Keys et al., 2016 for discussion.)

Pool size also varies widely. The bottom 10 percent of the universe consists of pools

with an outstanding balance of $5 million or below, while the top 10 percent has a balance

exceeding $20 billion. This dispersion reflects differences in original issue amount as

well as the fact that many older pools have partially or almost completely paid down.

7

The pool age closely corresponds to the age of the underlying loans, since agency mortgages are typically

securitized shortly after origination. See section 3 for more detail on the securitization process.

5

Pool size is much larger for Ginnie Mae multi-issuer pools than for the other categories.

Prepayment speed — a primary driver of security value — is also very heterogeneous

across pools. The median three-month prepayment speed, measured by the conditional

prepayment rate (CPR), is 27.8%, but the 5th and 95th percentiles are 2.6% and 52.6%

respectively. Section 4.2 discusses the drivers of prepayments.

To sum up, Table 1 shows that there is substantial heterogeneity and fragmentation

within the agency MBS universe, which consists of more than a million unique individual

pools. Even so, trading arrangements have evolved to facilitate a liquid, well-functioning

secondary market, with trading concentrated in a small number of forward contracts, as

we discuss in section 5.

2.4 International MBS markets

Outside the US, securitization is also used as a form of secondary market mortgage fi-

nance around the world, including China, continental Europe, Canada, the United King-

dom, and Australia.

Some countries share features of the US mortgage finance system. For example, the

Danish model is similar in many respects to agency securitization, as discussed by Berg

et al. (2018). Mortgages in Denmark are originated by a small number of specialist mort-

gage banks, which then issue bonds with cash flows matching the borrowers’ payments.

The mortgage bank retains the loan on balance sheet, however, and bears the credit risk

if the borrower defaults. In this sense, Danish mortgage banks play a role similar to Fan-

nie Mae and Freddie Mac. Another example is the Canadian model, which features a

significant role for government guarantees, with the public sector insuring all mortgages

with a downpayment of less than 20%. There is an active market for securitizing these

government-insured loans, with payments to investors guaranteed by the Canada Mort-

gage and Housing Corporation, a government agency also similar in some ways to Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac (Mordel and Stephens, 2015).

In most other countries, however, securitizations more closely resemble nonagency

MBS, with credit risk being borne by capital market investors.

8

Standard and Poor’s

(2021) provides an overview of market conditions for credit-sensitive MBS around the

8

E.g., Standard and Poor’s (2020) is a primer on the China RMBS market, which finances only a small share

of Chinese mortgage debt but has grown rapidly in recent years.

6

globe.

Covered bonds are a distinct but related form of capital market mortgage financing,

and are popular in many European countries.

9

Covered bonds are debt instruments that

finance a “cover pool” of ring-fenced assets. The bond investor has exclusive recourse to

the asset pool in case of default, with further recourse to the issuer’s other assets if needed

(see Berg et al. 2018). Unlike securitization, the cover pool is pledged as collateral for the

bonds but remains on the issuer’s balance sheet, and mortgage prepayment and default

therefore do not typically affect the payments to investors. The US does not have an

active covered bond market, in part because banks have access to funding collateralized

by mortgages through the Federal Home Loan Bank system (Bernanke, 2009).

3 Security design

Aside from the underlying mortgage type (residential or commercial) and the presence or

absence of a government-backed credit guarantee, MBS also differ in terms of how cash

flows from the mortgages are allocated to investors.

The most straightforward MBS design is provided by so-called “pass-through” securi-

ties. All cash flows — including scheduled principal and interest, as well as prepayments

— are paid to investors on a pro-rata basis, after first subtracting from the interest pay-

ments a fee to the loan servicer, and (in case of loans with a credit guarantee) the guarantee

fee (“g-fee”). This is how residential agency MBS pools are structured.

10

However, there are economic reasons to depart from the simple pass-through struc-

ture to appeal to investors with different needs and risk appetites. In the agency MBS

segment, pools are resecuritized into collateralized mortgage obligations (or CMOs) to

create tranches with different prepayment risk and duration. In a “sequential pay” struc-

9

E.g., see Prokopczuk et al. (2013) for a discussion and analysis of the German “Pfandbrief” covered bond

market and Meuli et al. (2021) for an analysis of the Swiss covered bond market, which shares features of

the Federal Home Loan Bank system. Berg et al. (2018) reports that the five largest covered bond markets

are Denmark, Germany, France, Spain and Sweden. As we have discussed above, however, Danish

covered bonds have the distinctive feature that market risk and prepayment risk are passed through to

investors, making these bonds more similar to agency MBS than to other covered bonds.

10

For GSE pools, the servicer fee is 25 basis points (bp), while the periodic g-fee is around 40-50bp. (Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac only disclose average effective g-fees, which include flow equivalents of required

upfront payments, so-called loan-level price adjustments. These average effective g-fees have hovered

between 50 and 60bp in recent years; see Urban Institute, 2021, p. 26.) For Ginnie Mae-backed loans, the

servicer fee is 44bp, while the guarantee fee is 6bp.

7

ture, principal prepayments are first only disbursed to class A bondholders until these

bonds are completely paid off; then to class B, and so on. This structure caters to in-

vestors with different maturity habitats — for example life insurers favor long-duration

assets to match their policy liabilities. Also popular, “stripped” CMOs separate cash flows

into interest-only (or IO) and principal-only (or PO) tranches. The universe also includes

many other security types; see Arcidiacono et al. (2013) for an overview. As of 2021 there

is $1.3 trillion in agency CMOs outstanding (source: SIFMA).

In the nonagency market, structured securities are used to allocate credit risk across

investors. Typically, nonagency CMOs follow a “senior-subordinated” structure, where

principal payments are directed first to the senior tranches, at least during an initial “lock-

out” period, while lower-ranked “mezzanine” tranches initially receive only coupon pay-

ments.

11

The lowest-ranked “equity” tranche is the first to absorb credit losses and there-

fore has the highest risk.

In the CMBS market, the most junior tranches are typically retained by the “special

servicer” (or “B-piece buyer”) who is also responsible for negotiating work-outs for delin-

quent loans. B-piece buyers therefore have strong incentives to carefully assess the credit

risk of the underlying loans before entering a deal, and are considered the gate-keepers

in the CMBS market (Ashcraft et al., 2019). Wong (2018), however, finds evidence that the

dual role of B-piece buyers as both investor and servicer leads to conflicts of interest with

senior bondholders during workouts.

3.1 Process of securitization

How are MBS actually produced? We here provide a brief overview for residential agency

MBS pools, following Fuster et al. (2013). See Bhattacharya et al. (2008) for a broader

discussion that also covers nonagency securities.

The building blocks for any MBS are individual loans. These are typically newly-

originated mortgages, but not always. The origination process begins with the borrower

and originator agreeing on the terms (interest rate, contract type, and upfront payments

including “points”). The loan originator could be a bank or a nonbank mortgage com-

11

During the housing and nonagency MBS boom that ended in 2007, these mezzanine tranches were then

pooled and re-securitized as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). These CDOs suffered very high credit

losses during the subsequent bust, including the AAA rated tranches (Cordell et al., 2019).

8

pany, with nonbanks accounting for about two-thirds of originations in recent years (see

Buchak et al., 2018, Kim et al., 2018 and Kim et al., 2022 for analysis of the growth of

nonbank lending and its implications for systemic risk). The terms are guaranteed by

the originator for a “lock period” of typically 30 to 90 days, during which time the bor-

rower’s application is evaluated and processed—in particular, to ensure that they fulfill

agency guidelines. Assuming the originator decides to fund the loan through an agency

securitization (rather than keeping the loan in portfolio), they may at this point already

forward-sell the loan in the TBA market, effectively hedging against changes in the value

of the loan during the lock period.

There are then two ways for the securitization to take place. In a “lender swap” trans-

action, the originator directly pools loans and delivers the pool to the securitizing agency

(e.g. Fannie Mae) in exchange for an MBS certificate, which can be subsequently sold

to investors in the secondary market (or delivered to them, if it had previously been

forward-sold). There are also multi-lender swaps, where loans from different sellers are

pooled into an MBS (e.g. Fannie Mae Majors) and sellers receive a proportional share of

the resulting pool. This is particularly relevant in the Ginnie Mae segment of the agency

market, where the Ginnie Mae II multi-issuer pool program accounts for 85-90 percent

of new MBS issuance (Tozer, 2019). The multi-issuer channel is particularly valuable for

smaller lenders that would not otherwise have the economies of scale to originate and

securitize government mortgages.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac also conduct “whole loan conduit” or “cash window”

transactions in which they purchase loans directly from originators (typically smaller

ones), pool these loans themselves, and sell the issued MBS in the secondary market.

The trade-off for originators is that the pricing obtained at the cash window is typically

worse, but the originator obtains liquidity immediately and does not face the risk of not

being able to assembling enough loans for a pool.

12

There is no cash window for Gin-

nie Mae MBS, because these pools are issued by private financial institutions rather than

Ginnie Mae itself.

12

According to https://www.machinesp.com/post/a-close-look-at-the-gse-cash-window, the share of

cash window transactions for Freddie Mac-issued pools has been 50% or more in recent years.

9

4 Risks to MBS investing, prepayment, and the OAS

MBS yields significantly exceed yields on risk-free securities reflecting the risks associated

with investing in MBS. We review these risks and then discuss prepayments, both their

measurement and their modeling. Finally, we delve more deeply into the valuation of

agency MBS through option-adjusted spreads (OAS).

4.1 Risks to MBS investing

Risks to MBS investing can be grouped into four main categories: duration, prepayment,

credit and liquidity.

Duration risk: MBS duration measures two closely related concepts. It is the weighted

average time until cash flows, which include both principal and interest payments, are

paid out to investors. But duration is also the sensitivity of the MBS price to a change

in the general level of interest rates. Because MBS pay fixed coupons to investors and

typically have 30-year maturities, duration is high and prices are very sensitive to interest

rates. A key distinguishing feature of MBS is that the duration of the security is not fixed

but rather uncertain because borrowers can prepay their loans at any time.

Prepayment risk: MBS prepayments are either voluntary or involuntary. Voluntary

prepayments are largely determined by borrowers’ refinancing and relocation decisions

while involuntary prepayments reflect defaults (see credit risk discussion below). Refi-

nancing is the most important source of prepayment, because for typical mortgages se-

curitized into agency MBS, the borrower can pay off the remaining balance at par with

no penalty. Since the mortgage rate is fixed, refinancing to a new loan is attractive when

market interest rates are low; therefore prepayments rise and MBS duration falls when

interest rates decline. In other words, MBS are callable securities, and price appreciation

from lower interest rates is therefore capped—MBS exhibit “negative convexity.”

Credit risk: At any point in time, borrowers can fail to make payments on the mort-

gages underlying an MBS. Default occurs when the loan no longer pays principal and

interest until liquidation. Default is often caused by a “double trigger” of negative eq-

uity and a negative life event such as unemployment, illness or divorce (e.g., Ganong and

Noel, 2020; Low, 2021).

13

Without such negative events, borrowers are generally reluctant

13

This double trigger is not a necessary condition for default, however. While most defaulters during and

10

to walk away from their mortgage and home even when equity is deeply negative (e.g.,

Bhutta et al., 2017). More generally, not all delinquencies turn into defaults as loans can

cure without “rolling” into more severe credit buckets.

The implications of default for investors depends on whether the MBS is an agency or

nonagency security. For agency MBS, the GSEs and Ginnie Mae promise full and timely

payment of principal and interest, a guarantee that is either explicitly or implicitly backed

by the federal government. When a borrower defaults, the issuer repurchases the loan

from the MBS pool at par, resulting in a prepayment event for MBS investors (an invol-

untary prepayment).

14

For nonagency MBS, however, borrower default is much more

significant because investors bear any credit losses, starting with the most junior security,

the equity tranche. Investors model probabilities of default and loss-given-default using

reduced-form models that include loan characteristics (e.g., LTVs, credit scores) as well

as macroeconomic variables.

15

Although agency MBS are essentially free of credit risk, in recent years the GSEs have

issued a new instrument — credit risk transfer (CRT) bonds — with cash flows explicitly

tied to credit losses on agency mortgages. CRTs are structured debt securities linked to

a “reference pool” of securitized loans. These bonds experience principal write-downs

if credit losses on the reference pool exceed particular thresholds. See Finkelstein et al.

(2018) for more details. CRTs were introduced to reduce the GSEs’ exposure to mortgage

credit risk by shifting some of the risk to the private sector. CRT secondary market prices

also provide a useful market signal about expected future mortgage credit losses; for

example CRT prices fell sharply at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic before recovering.

Trading and funding liquidity risk: MBS trading liquidity—the ease with which se-

curities can be traded—and funding liquidity—how easily MBS collateral is funded—are

additional risks to investing in MBS and influence returns (Brunnermeier and Pedersen,

2009; Song and Zhu, 2019). Trading liquidity varies quite significantly by type of MBS

after the financial crisis were indeed underwater on their mortgages, Low (2021) presents evidence that

the share of defaults with positive equity is quite high in “normal times.”

14

For MBS guaranteed by the GSEs, it is the relevant agency, Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, that repurchases

the mortgage. For Ginnie Mae pools, it is the financial institution that issued the security rather than

Ginnie Mae itself (Tozer, 2019). This is an important distinction, because the financial characteristics of the

issuer can affect their incentives to repurchase loans. For example bank issuers have been more likely to

repurchase nonperforming mortgages from Ginnie Mae pools during the COVID-19 pandemic because of

their stronger liquidity position.

15

See Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) for an example of this type of model.

11

— liquidity for private-label MBS is quite limited, but for agency MBS the TBA forward

market provides a high level of trading liquidity as well as funding liquidity through the

execution of dollar rolls (see section 5).

4.2 Measuring and modeling prepayments

We now turn to a more detailed discussion of prepayment risk, the most salient of these

four risks for agency MBS. For a given borrower, prepayment often involves paying down

the entire loan balance. Such an event only marginally reduces the overall MBS pool

balance though, because each pool is backed by many loans. Prepayment is measured

by the single monthly mortality (SMM), which is the fraction of an MBS balance prepaid

in a month relative to the remaining scheduled principal balance, and by the conditional

prepayment rate (CPR) which is simply the SMM expressed at an annual rate.

The blue line in the top panel of Figure 2 plots the time series of CPR for the aggregate

universe of 30-year fixed-rate agency MBS. Aggregating balances hides pool-specific pre-

payment variation, which is significant as shown earlier in Table 1. But even the aggregate

prepayment rate exhibits very wide variation, ranging from a CPR of about 55 percent

during the 2003 refinancing wave to a low of about 10 percent in 2008. The dashed red

line is the “moneyness” of the mortgage universe, which is the difference between the

average interest rate on the universe of outstanding mortgages and the current market

mortgage rate. When the moneyness of the universe increases, refinancing becomes more

attractive and prepayments therefore rise. Even so, similar levels of moneyness in 2003

and 2008 led to very different prepayment outcomes. A much greater degree of hetero-

geneity also exists at the level of specific pools. Prepayment modeling attempts to explain

this variation and to predict prepayments.

4.2.1 Modelling prepayments

The academic literature considers structural and rational models of mortgage prepay-

ment (e.g., Stanton, 1995), but practitioners rely on reduced-form statistical prepayment

models.

16

These models do not assume rational borrower behavior but use information

16

Popular statistical frameworks for modelling mortgage prepayment risk as well as credit risk include the

Cox proportional hazard model and the logit. See Deng et al. (2000) for a well-known competing risk

model of mortgage prepayment and default. Machine learning methods have also been applied to model

12

on observable borrower characteristics and macroeconomic factors to explain variation in

the SMM. Given the many variables and the complexity of the task, models from different

investors often disagree significantly about predicted prepayments (Carlin et al., 2014).

Explanatory variables in prepayment models can be logically grouped into those re-

lated to turnover, refinancing, and defaults and curtailments. The first two channels are

quantitatively the most important.

17

The turnover channel is associated with property

sales, which are affected by economic conditions and the strength of the housing market.

Turnover is highly seasonal, peaking in the summer, and is also subject to a “seasoning”

effect because sales are less likely during the first two to three years after a home purchase.

The refinancing channel exhibits the greatest variation over time and across pools. The

key variable used in modeling it is a pool’s moneyness: when moneyness is positive, a

borrower can lower their rate and monthly payment by refinancing—in other words, the

borrower’s prepayment option is “in-the-money” (ITM). Negative moneyness, instead,

means that refinancing (or selling the home and buying another) would increase the rate

paid—the borrower’s option is “out-of-the-money.”

4.2.2 Prepayment vs moneyness: the “S-curve”

The bottom panel of Figure 2 plots average prepayment rates as a function of moneyness

in a monthly panel of MBS indexed by coupon rate and year of origination. Reflecting

the shape of the relationship, this is known as an “S-curve.” While prepayments rise with

moneyness, on average, they never come close to reaching 100 percent.

18

This reflects

the fact that many borrowers fail to refinance when it is in their monetary interest to do

so (Keys et al., 2016). In addition, the S-curve bends down as pools become deeply ITM,

reflecting the so-called “burnout effect” — over time, an ITM mortgage pool becomes

less responsive to interest rates because the borrowers most sensitive to the refinancing

incentive have already exited.

The S-curve shifts over time due to changes in non-moneyness drivers of prepayment.

mortgage prepayment risk and credit risk in recent years (e.g., Sadhwani et al., 2021).

17

Curtailments are partial—rather than full—principal payments that often occur late in the life of a

mortgage. Defaults represent a prepayment event for the investor because of the agency credit guarantee,

as we have discussed. Default is however relatively unusual among pools issued by Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac, which typically consist of loans to prime borrowers.

18

Note that in constructing this curve, we bin together a large number of securities. At shown in 1 the

underlying variation at the level of single pools is much larger than what the S-curve would imply.

13

For instance, when interest rates hit multi-year lows, refinancing for given levels of mon-

eyness typically increases due to the “buzz” surrounding these low rates—this is known

as the “media effect” in prepayment modeling. This effect was prominent during the

record 2002-03 refinancing wave (Figure 2, top panel), and may also have contributed to

high prepayments during the COVID-19 pandemic after mortgage rates reached all-time

lows. Furthermore, an increase in “cash-out” refinancing to extract equity during a home

price boom can shift the S-curve upwards, while conversely, falling home prices and/or a

weak economy can make it difficult for borrowers to qualify for a refinancing, thereby re-

ducing prepayment for a given moneyness. Changes in agency underwriting guidelines

or government policies (such as the Home Affordable Refinance Program introduced in

the wake of the Great Recession) can also substantially shift prepayments.

Heterogeneity in refinancing across pools also reflects differences in creditworthiness

as measured by credit scores and LTVs, and loan size due to the fixed costs involved in

refinancing. State-level policies also matter (e.g., New York’s mortgage recording tax).

4.3 The OAS and risks to investing in agency MBS

We use the option-adjusted spread (OAS) to delve further into the risks associated with

agency MBS. The OAS is the most popular metric to assess agency MBS valuations and

risk premia. As shown by Boyarchenko et al. (2019), the OAS is equal to the average ex-

pected excess returns over the lifetime of the security.

19

Formally, the OAS is the constant

spread to baseline rates that sets the expected discounted value of cash flows equal to the

security’s market price after accounting for prepayments:

P

M

= E

T

∑

k=1

X

k

(r

k

)

∏

k

j=1

1 + OAS + r

j

, (1)

where P

M

is the market price of an MBS, r

j

is the riskless interest rate at time j and X

k

is the cash flow from the security. The OAS increases the larger the value of discounted

cash flows relative to the market price, meaning that when spreads are positive, MBS

19

In addition, period-by-period excess returns on an MBS can be expressed as the sum of carry income and

capital gains. In terms of the OAS, these are equal to the OAS itself plus the (negative) change in the OAS

with a weight equal to the MBS duration. One limitation of the OAS is that it is a model-derived measure

and thus subject to various assumptions.

14

trade below the discounted price net of the OAS.

20

The calculation of the expectation

term in the OAS uses Monte Carlo simulations and both a calibrated interest rate and an

estimated prepayment model. The two are combined to simulate interest rate paths and

corresponding prepayment flows to obtain model prices and spreads in (1).

21

We turn to data on OAS from a major dealer (JP Morgan) to present stylized facts both

in the time series and cross section of agency MBS. The top panel of Figure 3 shows the

evolution of Treasury OAS for the so-called current-coupon MBS, meaning the synthetic

coupon trading at par, issued by Fannie Mae.

This OAS averaged about 50 basis points since 2000, but spiked to about 150 basis

points in the fall of 2008, and turned negative at times during the periods of the QE3 and

QE4 programs, when the Federal Reserve purchased large quantities of agency MBS.

A negative OAS indicates that, after accounting for embedded prepayment option,

MBS are valued more highly than Treasuries. On face value this seems anomalous be-

cause Treasuries are more liquid than MBS, are explicitly issued by the federal govern-

ment, and are generally treated more favorably for regulatory purposes (e.g., bank cap-

ital and liquidity requirements). However, a negative OAS could for example be driven

by preferred-habitat effects or indicate that some investors reached for a higher yield be-

cause they cannot synthetically replicate the higher MBS zero-volatility yield by investing

in Treasuries and interest rate options. Note that in this case the MBS yield will always

exceed that on Treasuries, even when OAS are negative. A final explanation is simply

that there may model error leading to mismeasurement of the OAS.

The bottom panel of Figure 3 focuses on the cross section of OAS and reveals sub-

stantial variation across MBS with different moneyness levels.

22

In the cross section, a

20

Another commonly used metric is known as the zero-volatility spread. The ZVS abstract from rate

uncertainty and it is defined as:

P

M

=

T

∑

k=1

X

k

(Er

k

)

∏

k

j=1

1 + ZVS + Er

j

. (2)

The ZVS-OAS difference is known as the “option cost.” In computing the ZVS both cash flows and

discounts are evaluated along a single expected risk-neutral rate path, thus ignoring the effects of

uncertainty about the timing of prepayments on the MBS valuation. This implies that the ZVS will be

larger than the OAS.

21

The interest rate model is calibrated to the term structure of interest rates and volatility surface implied by

prices of interest rate derivatives. Once the paths for the interest rates are determined, the cash-flows are

obtained from the prepayment model.

22

Here we define moneyness as the difference between the MBS coupon rate and the current level of the

30-year fixed mortgage rate after adding a constant adjustment of 50 basis points. We make this

15

smile-like pattern emerges: spreads are lowest for securities for which the prepayment

option is at-the-money, and increase if the option moves out-of-the-money and especially

when it is in-the-money. The OAS smile pattern was first shown by Boyarchenko et al.

(2019), who also find that OAS predicts realized excess returns. A similar smile-shaped

pattern in MBS excess returns is documented by Diep et al. (2021).

Large positive average OAS over time and across securities suggest that MBS investors

require risk compensation to hold MBS over Treasuries. The embedded prepayment op-

tion means that even if payments are guaranteed, the timing of cash flows accruals is un-

certain. Equation (1) explicitly incorporates the feature that cash flows depend on interest

rates through prepayments. However, OAS abstracts from uncertainty related to non-

interest rate factors that affect prepayments, such as house prices and lending standards.

Boyarchenko et al. (2019) show that MBS investors earn risk compensation for these non-

interest-rate prepayment factors and that these factors underlie the cross-sectional smile

pattern in the OAS.

23

In the time series, Boyarchenko et al. (2019) further show that risk factors unrelated to

prepayment, such as liquidity or changes in the perceived strength of the implicit federal

government guarantee on the agencies, are important drivers of the average OAS. For

example, the non-prepayment component in the OAS co-moves with spreads on other

agency debt and corporate securities, reflecting shared risk factors.

4.4 Supply Effects and Fed Quantitative Easing

The supply of MBS — which is affected by the net volume of new issuance as well as Fed

MBS purchases that reduce the net supply available to private investors — is also posi-

tively related to the non-prepayment component of OAS. As an indication of these effects,

the OAS turned negative during QE3 and QE4 when the Fed purchased large quantities

of agency MBS (see grey bars in Figure 3, left panel). Consistent with this fact, event stud-

ies using high-frequency data find that announcements of new Fed MBS purchases are

adjustment because the mortgage note rates are typically around 50 basis points higher than the MBS

coupon due to the agency guarantee fee as well as servicing fees.

23

They arrive at this conclusion by using matched pairs of IO and PO strips that split a pool’s cash flows into

interest payments and principal payments. If a pair of strips is fairly valued relative to each other,

risk-neutral (or market implied) prepayment rates can be estimated as multiples of physical (realized)

ones. OAS computed under these alternative risk-neutral prepayments do not vary much in the cross

section, meaning that it is the prepayment risk premium that leads to the smile-shaped pattern.

16

associated with significant declines in MBS yields and OAS (Gagnon et al., 2011; Hancock

and Passmore, 2011; Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen, 2011). Chernov et al. (2016)

similarly find evidence that MBS risk premiums are affected by the Federal Reserve’s

quantitative easing programs using a more model-based approach. Krishnamurthy and

Vissing-Jorgensen (2011) and Di Maggio et al. (2020) furthermore show that MBS pur-

chases have larger effects on MBS yields than a comparable volume of Treasury pur-

chases, consistent with the presence of some degree of market segmentation. Kandrac

(2018) studies effects of Fed MBS purchases on market functioning and liquidity, finding

modest negative effects.

Other research investigates the broader financial and macroeconomic effects of the

Federal Reserve’s MBS purchases. For example, Di Maggio et al. (2020) find that Fed

QE significantly boosted refinancing activity and as a result, led to higher aggregate con-

sumption. Beraja et al. (2019) show that the effectiveness of QE and monetary policy more

generally depends on the distribution of home equity, because insufficient equity reduces

the ability of borrowers to refinance.

5 Trading

Most agency RMBS trading occurs through the to-be-announced or “TBA” forward mar-

ket. The key feature of a TBA trade is that the seller does not specify exactly which pools

will be delivered at settlement. Instead, the buyer and seller agree on six trade param-

eters: the agency, coupon, maturity, price, face value, and settlement month, and any

combination of pools satisfying the parameters and SIFMA good delivery guidelines can

be delivered at settlement.

24

The TBA market effectively concentrates the fragmented universe of around a mil-

lion individual agency MBS pools into a small number of liquid contracts for trading

purposes, thereby improving fungibility and liquidity.

25

Investors trade TBAs to express

24

For details of the good delivery guidelines for TBA settlement, see Chapter 8 of SIFMA (2021). The exact

CUSIPs to be delivered are specified two days prior to settlement. Settlement occurs once per month (e.g.,

for 30-year Uniform MBS, settlement day is typically between the 10th and 14th of the month). The TBA

settlement schedule is available at

https://www.sifma.org/resources/general/mbs-notification-and-settlement-dates/.

25

E.g., Gao et al. (2017) find that over a sample period of several years, 12 maturity-coupon combinations

accounted for 96% of TBA trades.

17

price views or for hedging. TBAs are also used by lenders to hedge their origination

pipeline, as discussed in section 3.

The TBA market can further be used as a funding vehicle, through the execution of

“dollar roll” transactions. In a dollar roll, the roll seller sells TBAs for a coming delivery

month (the “front” month) and simultaneously purchases TBAs for a later “back” month.

This provides short-term funding to the roll seller by postponing the date when she is

due to pay cash to settle her long TBA position. The substance of a dollar roll is similar

to a repurchase agreement, but there are some important differences; see Song and Zhu

(2019) for further discussion and empirical analysis of the dollar roll market. The Federal

Reserve has also used dollar rolls to support market functioning, and actively employed

this tool during the COVID-19 pandemic (Frame et al., 2021).

Since mid-2019, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac pools have traded through a single set

of “Uniform MBS” (UMBS) TBA contracts, in which pools issued by either agency can be

delivered at settlement. Previously, the two GSEs traded separately in the TBA market.

This change in market structure was implemented because TBA trading had historically

been highly concentrated in Fannie Mae contracts, leading to an illiquidity discount for

Freddie Mac pools which put them at a competitive disadvantage. Liu et al. (2021) find

that UMBS implementation successfully improved Freddie Mac TBA liquidity without

any obvious adverse effects on overall market functioning.

The agency market also features significant trading of individual pools (known as

“spec pool” trading). One reason for spec pool trading is that the TBA market operates

on a cheapest-to-deliver basis — sellers will deliver the least valuable eligible pools. This

leads to a semi-separating equilibrium in which more valuable “pay-up” MBS pools trade

individually while less valuable MBS trade on a pooled basis in the TBA market. See Li

and Song (2020) for a theoretical model of this structure. Specified pool trades are often

arranged to settle on TBA settlement dates, but can settle at any time of the month.

26

Specified pool trading also includes agency MBS pools that for various reasons are not

TBA-eligible.

27

Other mortgage securities, such as CMBS, agency CMOs, and nonagency

26

Chen et al. (2020) show that during the market turmoil of March 2020, stressed market participants

scrambled to raise cash by selling MBS in the specified pool market, temporarily driving spec pool prices

below TBA prices. To meet the demand for liquidity and stabilize the market, the Federal Reserve

responded by executing unconventional MBS purchases on a T+3 settlement basis.

27

TBA-ineligible pools include MBS with more than 10 percent of superconforming loans exceeding the

national conforming limit, and pools with LTVs exceeding 105 percent (Vickery and Wright, 2013; Huh

18

RMBS, also trade on an individual basis.

5.1 Evidence on trading activity and liquidity

Table 2 presents trading volume statistics based on TRACE data aggregated by SIFMA.

Agency residential MBS trading activity dwarfs the other segments of the market, with

$288bn of daily trading volume, compared to $2.7bn for CMBS and only $0.5bn for nona-

gency RMBS. This reflects $261bn of TBA trading (about 90% of the agency RMBS total),

followed by a smaller but still very significant $25.4bn of specified pool trades and $1.4bn

of agency CMOs.

Estimated trading costs are also significantly lower in the TBA market. Bessembinder

et al. (2013) estimate one-way trading costs of only 1 basis point (bp) for TBAs, compared

to 40bp for specified pools, and 39bp for nonagency MBS. Gao et al. (2017) find that TBA

liquidity has positive spillover effects on the specified pool market — trading costs are

lower for specified pools that are TBA eligible and for spec pool trades close to TBA

settlement dates. Huh and Kim (2020) trace out the broader effects of TBA liquidity using

a TBA-eligibility cutoff at the national conforming loan limit. TBA eligibility is estimated

to reduce mortgage rates by 7-28bp, and to spur refinancing activity.

Table 2 also compares MBS trading volume to activity in other US fixed income mar-

kets. TBA activity is lower than in the Treasury market, but trading volume is more than

six times higher than in the corporate bond market, despite the larger stock of corporate

bonds outstanding. Trading activity is even lower for municipal bonds, agency debt and

asset backed securities, and Bessembinder et al. (2020) further show that TBA trading

costs are much lower than for these other markets.

28

6 Economic effects of MBS and mortgage securitization

What are the broader economic effects of MBS markets and mortgage securitization? A

sizeable academic literature has studied different aspects of this question and also high-

and Kim, 2020). TBA eligibility rules are designed to limit heterogeneity within each cohort.

28

Bessembinder et al. (2020) and Gao et al. (2017) speculate that introducing a TBA-like forward market for

corporate bonds could improve liquidity in that market. Corporate bonds are more heterogeneous than

agency MBS, however, and the number of issuers is much higher, factors which would likely be hurdles to

implementing such an idea.

19

lighted potential downsides of securitization, especially in the wake of the Great Reces-

sion. In this section, we provide a brief overview of some of the main themes.

A key benefit of securitization is that it makes mortgages more liquid, thereby sig-

nificantly de-coupling loan originators’ ability to produce loans from their own financial

condition (e.g. funding, risk exposure). As evidence on this point, Loutskina and Stra-

han (2009) show that bank liquid assets and deposit costs play much less of a role in

the origination of conforming mortgages, which can easily be securitized, compared to

less-liquid jumbo mortgages. Securitization is also fundamental to the rise of nonbank

lenders (financed through wholesale funding) as the dominant origination channel in the

US (Buchak et al., 2020; Gete and Reher, 2020; Kim et al., 2022).

29

Since securitization increases liquidity and broadens the set of lenders able to originate

mortgages, one would naturally expect that it also leads to an outward shift in credit

supply, plausibly increasing credit access for otherwise “marginal” borrowers. However,

a sizeable literature has argued that securitization also reduces credit quality through an

additional “moral hazard” channel: as originators offload the credit risk, they may have

weaker incentives to screen borrowers, leading to lower acquisition of soft information

and worse ex-post outcomes (e.g., Keys et al., 2010; Nadauld and Sherlund, 2013; Rajan

et al., 2015; Choi and Kim, 2020). But the strength of the evidence, and the question of

whether securitization is an important cause of the US mortgage boom and bust of the

2000s, remains debated in the literature (e.g., Bubb and Kaufman, 2014; Foote et al., 2012,

2020; Mian and Sufi, 2021).

A related literature has focused on the effects of securitization on loan monitoring after

origination—in particular, whether the mortgage servicer has insufficient or misaligned

incentives to work out appropriate solutions (such as modifications) for delinquent loans.

Again, there is a debate in the literature about how important these incentive effects were

in explaining (non-)modifications of securitized mortgages during the Great Recession

(e.g., Piskorski et al., 2010; Agarwal et al., 2011; Adelino et al., 2013; Aiello, 2021). More

recently, Kim et al. (2021) find that mortgage servicers’ financial condition affects for-

bearance outcomes for securitized mortgages during the COVID-19 crisis. Related, Wong

(2018) finds evidence of misaligned servicer incentives in the CMBS market.

29

Without securitization, nonbank lenders could potentially sell whole loans to banks or other financial

institutions, but such a market would be far less liquid. Indeed, in the jumbo market, where securitization

is dormant since the Great Recession, nonbanks play a much smaller role than in the agency market.

20

Securitization may also affect mortgage contract design. Fuster and Vickery (2015)

show that lenders reduce the supply of long-term prepayable fixed-rate mortgages (rel-

ative to adjustable-rate mortgages) when securitization markets become illiquid. They

argue that this is due to lenders’ limited ability to absorb the interest rate and prepay-

ment risk embedded in FRMs.

30

Thus, it appears unlikely that the 30-year prepayable

FRM, which is by far the dominant mortgage type in the US, could be offered at similarly

competitive rates without liquid securitization markets.

In turn, the popularity of prepayable FRMs has broader consequences for financial

markets and the transmission of monetary policy. In particular, several studies argue that

“convexity hedging” flows lead to important interactions between the MBS market and

the Treasury yield curve (Hanson, 2014; Malkhozov et al., 2016; Hanson et al., 2021). Fur-

thermore, the fact that US borrowers need to refinance to benefit from a drop in market

interest rates means there is much less direct transmission of monetary policy to house-

hold balance sheets than in a system with adjustable-rate mortgages (e.g. Campbell, 2013;

Di Maggio et al., 2017). Transmission is further blunted by the limited ability of mortgage

originators to increase origination capacity during periods of peak demand; instead, orig-

inators tend to earn high markups during such periods (Fuster et al., 2013, 2017, 2021).

7 Directions for future research

The MBS market was a relatively neglected research topic prior to the 2008 financial cri-

sis, but the literature has grown rapidly in the years since. Rich loan- and security-level

datasets are now available to researchers, and the introduction of TRACE data for struc-

tured products in 2011 provides new opportunities to study MBS microstructure and liq-

uidity. We end this paper by highlighting some topics that we believe present opportuni-

ties for future research.

1. Securitization and alternative mortgage designs. Various alternative mortgage de-

signs have been proposed to improve macroeconomic stability, reduce transaction

costs, or produce other benefits. For instance, Eberly and Krishnamurthy (2014),

Guren et al. (2021), and Campbell et al. (2021) study mortgages that can switch

30

Recent work by Xiao (2021) shows that this ability varies in the cross section of banks depending on their

funding structure, which in turn affects their propensity to securitize mortgages.

21

from FRMs to ARMs or interest-only loans during recessions, while Greenwald et al.

(2021) study shared appreciation mortgages with payments that adjust with home

prices. An open question is how such alternative products would be funded and

what role securitization markets would play. Securitization may in fact hinder in-

novation, in the sense that the existence of a thick, liquid secondary market for a

particular contract —30-year FRMs—may present a barrier for alternative designs.

2. What’s holding back nonagency securitization? Nonagency securitization remains

far lower than prior to the financial crisis, despite the much higher credit guarantee

fees now charged by the GSEs. Stricter post-crisis regulation is a natural reason

why, as discussed in section 2.1. But research has not clearly disentangled the role

of regulation from other factors such as changes in expectations.

3. Investor behavior. There is limited research on the determinants of investor behav-

ior in the MBS market (e.g., the striking fact that MBS now make up half of bank

security portfolios) and how investors affect pricing and liquidity.

31

4. Securitization and climate change. An emerging literature studies the interaction

between climate change and mortgage and MBS markets (e.g., Ouazad and Kahn,

2019). This is likely to be a fruitful topic for future work. For instance, securitization

prices can provide useful high-frequency information about the market’s assess-

ment of climate and natural disaster risk. Another application: Fannie Mae has de-

veloped a “green MBS” program for loans backed by buildings with green building

certifications — to our knowledge, its effects have not been rigorously studied.

To sum up, mortgage-backed securities are at the very heart of housing finance and

the US financial system, and also play a significant role in monetary policy and monetary

transmission. The MBS market also presents many opportunities for academics, and this

important market is likely to remain a vibrant topic for research in the years to come.

31

One contribution along those lines is by Erel et al. (2013), who study the drivers of bank investments in

nonagency MBS tranches.

22

Figure 1: Mortgage-backed securities outstanding

0

20

40

60

80

100

% of residential mortgage debt

0

10

20

30

40

50

% nominal GDP

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

agency RMBS, % nominal GDP (LHS)

non-agency RMBS, % nominal GDP (LHS)

RMBS, % residential mtg debt (RHS)

0

10

20

30

% of commercial mortgage debt

0

2

4

6

% of nominal GDP

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

agency CMBS, % nominal GDP (LHS)

non-agency CMBS, % nominal GDP (LHS)

CMBS, % commercial mtg debt (RHS)

Shaded areas represent stock of agency and nonagency MBS as a percent of nominal GDP. Dashed line

plots total MBS scaled by the relevant stock of mortgage debt. See Appendix (section A) for details of figure

construction. Data sources: FAUS, BEA.

23

Figure 2: CPR for agency MBS

-1

-.5

0

.5

1

1.5

Moneyness, percent

0

20

40

60

CPR, percent

2000m1 2005m1 2010m1 2015m1 2020m1

CPR

Moneyness

10

15

20

25

30

CPR, percent

-2 0 2 4 6

Moneyness, percent

The top panel shows the time series of the monthly conditional prepayment rate (CPR) on the universe of

30-year fixed-rate agency MBS weighted by their remaining principal balance, against the moneyness of

the mortgage universe. Moneyness is calculated as the weighted average coupon rate (WAC) minus the

monthly average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage rate. The bottom panel shows a binned scatter plot (Cattaneo

et al., 2019) of the cross-sectional variation in CPR as a function of their moneyness. All data is monthly

and covers the period 2000-2021. Source: eMBS; Freddie Mac.

24

Figure 3: Time-series and cross-sectional variation of the agency OAS.

QE1 QE3 QE4

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Basis Points

Jan00 Jan03 Jan06 Jan09 Jan12 Jan15 Jan18 Jan21

20

40

60

80

Basis points

-.01 0 .01 .02 .03

Moneyness

The top panel shorts the time series of the option-adjusted spread (to Treasuries and averaged each month)

on the current-coupon agency MBS. The red line is the sample average and shaded areas represent periods

in which the Federal Reserve purchased agency MBS in QE programs. The bottom panel shows a binned

scatter plot (Cattaneo et al., 2019) of the cross-sectional variation in the OAS across MBS coupons as a

function of their moneyness. Moneyness is calculated as the coupon rate plus 50 basis points (to account

for servicing and the guarantee fee) minus the monthly average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage rate. The

bottom panel only includes coupons with remaining principal balance of at least 100 million. All data is

monthly average and covers the period 2000-2021. Source: JP Morgan; Freddie Mac.

25

Table 1: The cross-section of agency MBS pools

Fannie Mae Freddie Mac Ginnie Mae Total

Multi Other

Number of Active Pools 474,062 274,588 8,547 246,025 1,003,222

Aggregate Outstanding Face Value (UPB, in billions)

30yr FRM 2,590.1 1,902.8 1,575.8 386.3 6,455.1

15yr FRM 450.8 339.8 24.5 3.6 818.7

Other FRM 204.2 127.9 0.0 0.3 332.4

Other Mortgage Types 34.4 26.7 10.6 46.6 118.3

Total 3,279.5 2,397.2 1,610.9 436.9 7,724.5

TBA eligible (%, weighted by UPB) 94.1 94.1 96.2 21.3 90.5

Distribution of Pool UPB

10th pctile 4.3 6.2 754.2 1.0 5.0

50th pctile 165.0 287.8 6,226.6 6.2 353.3

90th pctile 26,654.0 6,956.9 34,823.1 36.8 19,598.8

95th pctile 35,199.7 8,932.9 40,937.4 58.6 34,823.1

99th pctile 41,203.9 12,348.9 43,895.2 144.2 41,203.9

Distribution by Coupon (weighted by UPB)

less than 2 0.05 0.09 0.01 0.03 0.05

2-2.5 0.24 0.27 0.16 0.07 0.22

2.5-3 0.18 0.17 0.20 0.18 0.18

3-3.5 0.20 0.18 0.25 0.14 0.20

3.5-4 0.15 0.13 0.22 0.19 0.16

4-4.5 0.11 0.09 0.10 0.17 0.10

greater than 4.5 0.07 0.07 0.06 0.22 0.08

Distribution of Pool Age (%, weighted by UPB)

less than 1yr 41.92 47.44 38.52 27.44 42.11

1-5yr 32.69 30.81 40.84 41.71 34.32

5-10yr 20.38 17.43 17.87 18.52 18.84

greater than 10yr 5.01 4.32 2.77 12.32 4.74

Distribution of Prepayment Speed (weighted by UPB)

1st pctile 0.05 0.10 7.52 0.00 0.04

5th pctile 1.87 3.60 9.83 0.01 2.64

25th pctile 13.90 13.24 27.86 3.84 14.82

50th pctile 24.88 23.91 40.34 23.22 27.80

75th pctile 36.26 35.63 47.23 38.81 40.03

95th pctile 50.88 48.93 55.88 66.92 52.57

99th pctile 66.09 61.90 59.98 87.32 66.10

Reflects the population of agency residential MBS pools measured as of March 2021. All averages and

distributional statistics are weighted by outstanding pool unpaid balance. Source: Author calculations

based on eMBS security-level data.

26

Table 2: MBS trading volume

Avg. daily

trading volume

($bn)

A. Residential: Agency MBS

TBA 260.95

Specified Pool 25.34

CMO 1.37

Total 287.67

B. Residential: Non-agency MBS

CMO (IO/PO) 0.05

CMO (P&I) 0.43

Total 0.48

C. Commercial MBS

Agency CMBS 1.22

Non-Agency CMBS (IO/PO) 0.28

Non-Agency CMBS (P&I) 0.74

Total 2.71

Memo: other USD fixed income securities

US Treasury 603.2

Corporate debt 38.9

Municipal bonds 12.0

Federal agency securities 5.3

Asset backed securities 1.9

Average daily trading volume is calculated over the period from January to September 2021. IO/POs are

stripped passthrough pools that pay either interest only or principal only, whereas P&I CMOs are typically

sequential pay bonds with cashflows derived from both principal and interest payments on the underlying

mortgages. Source: SIFMA, aggregated from FINRA TRACE data.

27

References

ADELINO, M., K. GERARDI, AND P. S. WILLEN (2013): “Why Don’t Lenders Renegotiate More

Home Mortgages? Redefaults, Self-Cures and Securitization,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 60,

835–853.

ADELINO, M., W. B. MCCARTNEY, AND A. SCHOAR (2020): “The Role of Government and Pri-

vate Institutions in Credit Cycles in the U.S. Mortgage Market,” Working Papers 20-40, Federal

Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

ADELINO, M., A. SCHOAR, AND F. SEVERINO (2016): “Loan Originations and Defaults in the

Mortgage Crisis: The Role of the Middle Class,” Review of Financial Studies, 29, 1635–1670.

AGARWAL, S., G. AMROMIN, I. BEN-DAVID, S. CHOMSISENGPHET, AND D. D. EVANOFF (2011):

“The role of securitization in mortgage renegotiation,” Journal of Financial Economics, 102, 559–

578.

AIELLO, D. J. (2021): “Financially constrained mortgage servicers,” Journal of Financial Economics,

forthcoming.

AN, X., Y. DENG, AND S. GABRIEL (2009): “Value Creation through Securitization: Evidence from

the CMBS Market,” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 38, 302–326.

ARCIDIACONO, N., L. CORDELL, A. DAVIDSON, AND A. LEVIN (2013): “Understanding and

Measuring Risks in Agency CMOs,” Working paper no. 13-8, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadel-

phia.

ASHCRAFT, A. AND T. SCHUERMANN (2008): “Understanding the Securitization of Subprime

Mortgage Credit,” Foundations and Trends in Finance, 2, 191–309.

ASHCRAFT, A. B., K. GOORIAH, AND A. KERMANI (2019): “Does skin-in-the-game affect security

performance?” Journal of Financial Economics, 134, 333–354.

BERAJA, M., A. FUSTER, E. HURST, AND J. VAVRA (2019): “Regional Heterogeneity and the Refi-

nancing Channel of Monetary Policy,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134, 109–183.

BERG, J., M. B. NIELSEN, AND J. VICKERY (2018): “Peas in a pod? Comparing the U.S. and Danish

mortgage finance systems,” Staff Reports 848, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

28

BERNANKE, B. (2009): “The Future of Mortgage Finance in the United States,” B.E. Journal of

Economic Analysis & Policy, 9, 1–10.

BESSEMBINDER, H., W. F. MAXWELL, AND K. VENKATARAMAN (2013): “Trading Activity and

Transaction Costs in Structured Credit Products,” Financial Analysts Journal, 69, 55–67.

BESSEMBINDER, H., C. SPATT, AND K. VENKATARAMAN (2020): “A Survey of the Microstructure

of Fixed-Income Markets,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 55, 1–45.

BHATTACHARYA, A. K., W. S. BERLINER, AND F. J. FABOZZI (2008): “The Interaction of MBS

Markets and Primary Mortgage Rates,” Journal of Structured Finance, 14, 16–36.

BHUTTA, N., H. SHAN, AND J. DOKKO (2017): “Consumer Ruthlessness and Mortgage Default

during the 2007 to 2009 Housing Bust,” Journal of Finance, 72, 2433–2466.

BOYARCHENKO, N., A. FUSTER, AND D. O. LUCCA (2019): “Understanding mortgage spreads,”

Review of Financial Studies, 32, 3799–3850.

BRUNNERMEIER, M. K. AND L. H. PEDERSEN (2009): “Market Liquidity and Funding Liquidity,”

Review of Financial Studies, 22, 2201–2238.

BUBB, R. AND A. KAUFMAN (2014): “Securitization and moral hazard: Evidence from credit score

cutoff rules,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 63, 1 – 18.

BUCHAK, G., G. MATVOS, T. PISKORSKI, AND A. SERU (2018): “Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage,

and the Rise of Shadow Banks,” Journal of Financial Economics, 130, 453–483.

——— (2020): “Beyond the Balance Sheet Model of Banking: Implications for Bank Regulation

and Monetary Policy,” Working Paper 25149, National Bureau of Economic Research.

BURGESS, G., W. PASSMORE, AND S. SHERLUND (2022): “The Government Agencies,” This Vol-

ume.

CALEM, P., F. COVAS, AND J. WU (2013): “The Impact of the 2007 Liquidity Shock on Bank Jumbo

Mortgage Lending,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 45, 59–91.

CAMPBELL, J. Y. (2013): “Mortgage Market Design,” Review of Finance, 17, 1–33.

CAMPBELL, J. Y., N. CLARA, AND J. F. COCCO (2021): “Structuring Mortgages for Macroeconomic

Stability,” Journal of Finance, 76, 2525–2576.

29

CARLIN, B. I., F. A. LONGSTAFF, AND K. MATOBA (2014): “Disagreement and Asset Prices,”

Journal of Financial Economics, 114, 226–238.

CATTANEO, M. D., R. K. CRUMP, M. H. FARRELL, AND Y. FENG (2019): “On binscatter,” arXiv

preprint arXiv:1902.09608.

CHANDAN, S. (2012): “The Past, Present, and Future of CMBS,” Tech. rep.

CHEN, J., H. LIU, A. SARKAR, AND Z. SONG (2020): “Dealers and the Dealer of Last Resort:

Evidence from MBS Markets in the COVID-19 Crisis,” Staff Reports 933, Federal Reserve Bank

of New York.

CHERNOV, M., B. R. DUNN, AND F. A. LONGSTAFF (2016): “Macroeconomic-Driven Prepayment

Risk and the Valuation of Mortgage-Backed Securities,” Working Paper 22096, National Bureau

of Economic Research.

CHOI, D. B. AND J.-E. KIM (2020): “Does Securitization Weaken Screening Incentives?” Journal of

Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 1–43.

CORDELL, L., G. FELDBERG, AND D. SASS (2019): “The Role of ABS CDOs in the Financial Crisis,”

Journal of Structured Finance, 25, 10–27.

CREDIT SUISSE (2011): “Agency CMBS Market Primer,” Tech. rep.

DAVIDSON, A. AND A. LEVIN (2014): Mortgage Valuation Models: Embedded Options, Risk, and

Uncertainty, Oxford University Press.

DEFUSCO, A. A., S. JOHNSON, AND J. MONDRAGON (2019): “Regulating Household Leverage,”

Review of Economic Studies, 87, 914–958.

DEMYANYK, Y. AND O. VAN HEMERT (2011): “Understanding the subprime mortgage crisis,”

Review of Financial Studies, 24, 1848–1880.

DENG, Y., J. M. QUIGLEY, AND R. VAN ORDER (2000): “Mortgage Terminations, Heterogeneity

and the Exercise of Mortgage Options,” Econometrica, 68, 275–307.

DI MAGGIO, M., A. KERMANI, B. J. KEYS, T. PISKORSKI, R. RAMCHARAN, A. SERU, AND V. YAO

(2017): “Interest Rate Pass-Through: Mortgage Rates, Household Consumption, and Voluntary

Deleveraging,” American Economic Review, 107, 3550–88.

30

DI MAGGIO, M., A. KERMANI, AND C. J. PALMER (2020): “How Quantitative Easing Works:

Evidence on the Refinancing Channel,” Review of Economic Studies, 87, 1498–1528.

DIEP, P., A. L. EISFELDT, AND S. RICHARDSON (2021): “The Cross Section of MBS Returns,”

Journal of Finance, 76, 2093–2151.

EBERLY, J. AND A. KRISHNAMURTHY (2014): “Efficient Credit Policies in a Housing Debt Crisis,”

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 45, 73–136.

EREL, I., T. NADAULD, AND R. M. STULZ (2013): “Why Did Holdings of Highly Rated Securiti-

zation Tranches Differ So Much across Banks?” Review of Financial Studies, 27, 404–453.

FABOZZI, F. J., ed. (2016): The Handbook of Mortgage-Backed Securities, Oxford University Press, 7th

ed.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF NEW YORK (2021): “Quarterly Trends for Consolidated U.S. Banking

Organizations,” Second Quarter.

FINKELSTEIN, D., A. STRZODKA, AND J. VICKERY (2018): “Credit risk transfer and de facto GSE

reform,” Economic Policy Review, 88–116.

FOOTE, C. L., K. S. GERARDI, AND P. S. WILLEN (2012): “Why Did So Many People Make So

Many Ex Post Bad Decisions? The Causes of the Foreclosure Crisis,” Working Paper 18082,

National Bureau of Economic Research.

FOOTE, C. L., L. LOEWENSTEIN, AND P. S. WILLEN (2020): “Cross-Sectional Patterns of Mortgage

Debt during the Housing Boom: Evidence and Implications,” Review of Economic Studies, 88,

229–259.

FRAME, W. S., A. FUSTER, J. TRACY, AND J. VICKERY (2015): “The Rescue of Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29, 25–52.

FRAME, W. S., B. GREENE, C. HULL, AND J. ZORSKY (2021): “Fed’s Mortgage-Backed Securities

Purchases Sought Calm, Accommodation During Pandemic,” Tech. rep., Dallas Fed Economics.

FUSTER, A., L. GOODMAN, D. LUCCA, L. MADAR, L. MOLLOY, AND P. WILLEN (2013): “The

Rising Gap between Primary and Secondary Mortgage Rates,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review, 19, 17–39.

31

FUSTER, A., A. HIZMO, L. LAMBIE-HANSON, J. VICKERY, AND P. S. WILLEN (2021): “How Re-

silient Is Mortgage Credit Supply? Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Working Paper

28843, National Bureau of Economic Research.