Baseline Housing Initiatives Report i January 23, 2023

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

ii January 23, 2023

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we’d like to thank Jotika Shetty and Jessica Gribben for their assistance and

oversight in this project. Their guidance, feedback, and assistance were invaluable as our team

were introduced to Richland County and its communities. They continuously pushed the project

in directions that will be crucial in informing the county’s housing efforts going forward.

We’d also like to thank members of the Housing Steering Committee for their review and guidance

on the project’s deliverables: Adrian Ackerman, Steve Andrews, Kelly Blankenship, Terry Carter,

Amy Hamrick, Alan Mitchell, Rebecca Owens, Duana Patton, Jodie Perry, Allie Watson, and Mike

Whisler.

Many others were invaluable in providing access to local data and troubleshooting any issues we

had with the data. We would especially like to thank Kara Russell at the Richland County Building

Department and Marc Milliron at the City of Mansfield Building Codes and Permit Department for

their help in securing permitting data. In addition, we’d like to thank Sherri Heyde, Amy Huff, and

Patrick Dropsey at the Richland County Auditor’s Office and Wendy Hunt at the Mansfield

Association of Realtors for their help in accessing local sales data. We’d also like to thank Jean

Taddie and David Gentile at the Richland County Regional Planning Commission for their help in

accessing transit and GIS data.

We’d also like to thank Duana Patton, Michelle Deskins, and Nicole Williams for graciously allowing

us to use their space at the Area Agency on Aging for our stakeholder meetings. We’d also like

to thank Allie Watson and Brady Groves at the Richland County Foundation for hosting our

strategy meetings.

Funding for this project was graciously provided by Richland County, the City of Mansfield, the

City

OF Ontario, the City of Shelby, the Village of Bellville, and the Village of Lexington

At Community Science, we’d like to thank Letia Brown and Kate Williams for their behind-the-

scenes project management oversight, Dillon Nguyen for his diligent notetaking and plan review,

and Gregory Mitchell for his assistance with mapping and creating the permitting dashboard.

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

iii January 23, 2023

Finally, we extend our thanks to the dozens of stakeholders who participated in our three in-

person meetings and the strategy sessions and to the clients of the Mansfield Metropolitan

Housing Authority who shared their experiences seeking affordable housing in Richland County.

Their participation and feedback were crucial in crafting this document.

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

iv January 23, 2023

Contents

Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... ii

Contents ...................................................................................................................... iv

Exhibits........................................................................................................................ vi

Executive Summary .................................................................................................... ix

Baseline Housing Initiatives Report .................................................................................... x

Housing Inventory Report .................................................................................................. xi

Market Analysis ............................................................................................................... xiii

Housing Needs Assessment ............................................................................................. xiv

Strategy Guide and Action Plan ......................................................................................... xv

Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1

Types of Housing Considered ............................................................................................. 2

Nodes .............................................................................................................................. 2

Data Sources .................................................................................................................... 3

Chapter 1: Baseline Housing Initiatives Report ......................................................... 5

Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 6

Plan Review ...................................................................................................................... 9

Stakeholder Feedback ..................................................................................................... 11

Housing Services and Programs Offered ........................................................................... 18

Identifying Nodes ........................................................................................................... 23

Chapter 2: Housing Data Inventory ........................................................................... 25

Introduction and Methods ............................................................................................... 26

Population Projections ..................................................................................................... 29

Census Demographic Data ............................................................................................... 30

Census Housing Data ...................................................................................................... 36

Vacancy Data ................................................................................................................. 44

Subsidized Housing Units ................................................................................................. 45

Historic Housing Unit Counts ........................................................................................... 46

Mortgage, Home Sales, and Inventory Data ...................................................................... 48

Permitting Data .............................................................................................................. 52

Employment and Commuting Data ................................................................................... 54

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

v January 23, 2023

Static Maps ..................................................................................................................... 62

Chapter 3: Market Analysis ........................................................................................ 73

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 74

Data Sources .................................................................................................................. 74

Overall Real Estate Trends ............................................................................................... 75

Market Rate Housing ....................................................................................................... 83

Attainable Housing Analysis ............................................................................................. 92

Affordable Housing Analysis ............................................................................................. 95

Conclusions and Summary .............................................................................................. 102

Chapter 4: Richland County Housing Needs Assessment ........................................ 105

Introduction .................................................................................................................. 106

Tax Delinquencies and Demolitions ................................................................................. 106

Land Use and Zoning ..................................................................................................... 107

Projecting Housing Needs ............................................................................................... 109

Estimating Economic Development Impacts of Addressing Housing Needs ......................... 119

Identifying Housing Needs and Recommendations ........................................................... 122

Chapter 5: Strategy Guide and Action Plan ............................................................. 124

Introduction .................................................................................................................. 125

Funding and Capacity for Housing Development .............................................................. 126

Crafting Policies that Promote Housing Development........................................................ 137

Increasing the Availability of Affordable and Transitional Housing ..................................... 146

Summary and Conclusions .............................................................................................. 153

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

vi January 23, 2023

Exhibits

Exhibit 1: Summary of housing categories ............................................................................. 8

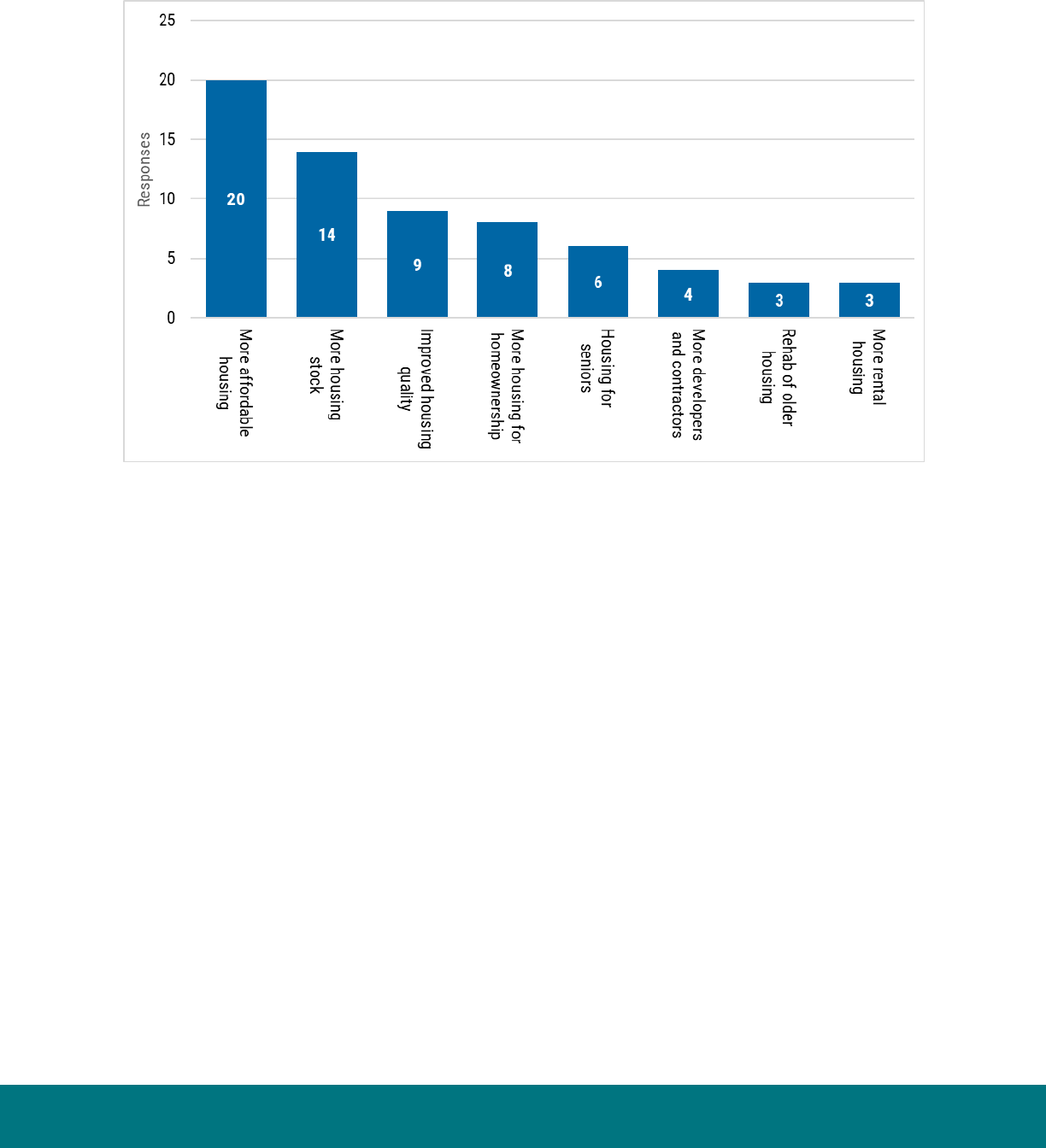

Exhibit 2: Responses to 'What is the Greatest Housing Need in Your Community?" ................. 16

Exhibit 3: Responses to "What do you see as the housing-related capacity that could be improved

in Richland County?" .......................................................................................................... 17

Exhibit 4: Analytic nodes for the Housing Needs Assessment ................................................ 24

Exhibit 5: Interpolation example.......................................................................................... 27

Exhibit 6: Example interpolation data .................................................................................. 27

Exhibit 7: Node interpolation by Census tract ....................................................................... 28

Exhibit 8: Richland County population projections ................................................................ 29

Exhibit 9: Racial composition by node .................................................................................. 30

Exhibit 10: Educational attainment by node ......................................................................... 31

Exhibit 11: Age by node ..................................................................................................... 32

Exhibit 12: Richland County population distribution .............................................................. 33

Exhibit 13: Poverty status ................................................................................................... 34

Exhibit 14: Population with a disability ................................................................................. 34

Exhibit 15: Population with a disability by type of disability ................................................... 35

Exhibit 16: Housing counts and tenure ................................................................................ 36

Exhibit 17: Units in structure ............................................................................................... 37

Exhibit 18: Size of housing unit ........................................................................................... 38

Exhibit 19: Year built .......................................................................................................... 38

Exhibit 20: Year residents moved into their housing unit ....................................................... 39

Exhibit 21: Contract rent ..................................................................................................... 39

Exhibit 22: Housing problems by node ................................................................................. 40

Exhibit 23: Gross rent as a percent of income ...................................................................... 41

Exhibit 24: Selected Monthly Homeownership Costs as a Percent of Household Income (SMOCAPI)

......................................................................................................................................... 41

Exhibit 25: Owner-occupied units by age ............................................................................. 42

Exhibit 26: Renter-occupied units by age ............................................................................. 42

Exhibit 27: Share of owner- and renter-occupied households with own children in housing unit

......................................................................................................................................... 43

Exhibit 28: Residential vacant units and vacancy rates.......................................................... 45

Exhibit 29: Subsidized units by node ................................................................................... 46

Exhibit 30: Historic housing unit counts by node .................................................................. 47

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

vii January 23, 2023

Exhibit 31: Historic housing counts for Mansfield, rural, and urban townships ........................ 47

Exhibit 32: Historic housing counts for Bellville, Lexington, Ontario, and Shelby ..................... 48

Exhibit 33: Relevant HMDA data .......................................................................................... 48

Exhibit 34: Zillow Home Value Index (ZHVI) for Mansfield and peer MSAs ............................. 50

Exhibit 35: Housing inventories for Mansfield and peer MSAs ................................................ 51

Exhibit 36: Richland County single-family permits ................................................................. 52

Exhibit 37: City of Mansfield new home construction permits ................................................ 53

Exhibit 38: City of Mansfield demolition data ........................................................................ 53

Exhibit 39: Richland County residents commuting to work (commute out) ............................. 55

Exhibit 40: Where workers in Richland County reside (commute in) ...................................... 55

Exhibit 41: Home area profile: age ...................................................................................... 56

Exhibit 42: Home area profile: earnings ............................................................................... 57

Exhibit 43: Home area profile: educational attainment .......................................................... 57

Exhibit 44: Home area profile: industry ................................................................................ 58

Exhibit 45: Work area profile: age ....................................................................................... 59

Exhibit 46: Work area profile: earnings ................................................................................ 59

Exhibit 47: Work area profile: educational attainment ........................................................... 60

Exhibit 48: Work area profile: industry ................................................................................. 61

Exhibit 57: Predominant racial/ethnic group by Census tract (map) ....................................... 62

Exhibit 52: Percent of population with a Bachelor's degree (map) ......................................... 63

Exhibit 49: Percent of population age 65 and older (map) ..................................................... 64

Exhibit 56: Poverty rate and tracts of concentrated poverty (map) ........................................ 65

Exhibit 51: Percent of population with a disability (map) ....................................................... 66

Exhibit 54: Homeownership rate (map) ............................................................................... 67

Exhibit 58: Percent of housing units that are single-family detached homes (map) ................. 68

Exhibit 55: Density of mobile homes by Census tract (map) .................................................. 69

Exhibit 59: Predominant year built of housing units by Census tract (map) ............................ 70

Exhibit 50: Median contract rent (map) ............................................................................... 71

Exhibit 53: Percent of renter households paying over 30% of their income toward rent and utilities

(map) ................................................................................................................................ 72

Exhibit 60: Single-family permits by node (Richland County) ................................................. 76

Exhibit 61: Single-family permits by jurisdiction, 2012–2021 ................................................. 77

Exhibit 62: Two- and three-family permits by node (Richland County) ................................... 78

Exhibit 63: Richland County multifamily permits by node, 2002–2021 .................................... 78

Exhibit 64: City of Mansfield new home construction permits ................................................ 79

Exhibit 65: Richland County housing units sold, January 2017–July 2022 ............................... 80

Exhibit 66: Average sales price, January 2017–July 2022 ...................................................... 81

Exhibit 67: Total sales volume, January 2017–July 2022 ....................................................... 81

Exhibit 68: New listings and for-sale inventory, January 2018–July 2022: .............................. 82

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

viii January 23, 2023

Exhibit 69: Median days from listing to pending ................................................................... 83

Exhibit 70: Richland County sales prices by tiers .................................................................. 84

Exhibit 71: Year-over-year price change, home sales by market tier, January 2013–July 2022 85

Exhibit 72: Home sales by bedroom size, January 2000–July 2022 ........................................ 86

Exhibit 73: Average condo price, January 2000–July 2022 .................................................... 87

Exhibit 74: Richland County contract rents, 2015 and 2019 ................................................... 94

Exhibit 75: Federally subsidized housing inventory by node .................................................. 97

Exhibit 76: Assisted units by targeted population ................................................................. 97

Exhibit 77: Gross rent as a percent of household income for renters in Richland County, by node

......................................................................................................................................... 99

Exhibit 78: Clients served at Harmony House, 2021 and 2022. ............................................. 100

Exhibit 79: Clients served at Harmony House by age range, 2021 and 2022 ......................... 100

Exhibit 80: Changes in Richland County homeowners and renters by age ............................. 111

Exhibit 81: Changes in Richland County homeowners and renters by age cohort ................... 112

Exhibit 82: Richland County housing needs projections, 2032 .............................................. 112

Exhibit 83: Projected rental housing supply by rent, 2032 .................................................... 115

Exhibit 84: Projected owner-occupied housing supply by mortgage costs, 2032 .................... 116

Exhibit 85: Estimates of income and household size for renter households in Richland County,

2032 ................................................................................................................................ 116

Exhibit 86: Estimates of income and household size for owner households, 2032 .................. 116

Exhibit 87: Projecting Richland County affordable housing needs for renter households, 2032118

Exhibit 88: Projecting Richland County affordable housing needs for owner households, 2032

........................................................................................................................................ 119

Exhibit 89: Economic impact of building 100 new single-family homes .................................. 121

Exhibit 90: Economic impact of building 100 rental apartments ............................................ 121

Exhibit 91: Economic impact of spending $1 million in home remodeling .............................. 122

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

ix January 23, 2023

Executive Summary

This Richland County Housing Needs Assessment and Action Plan is the product of over 10

months of data analysis and community conversations regarding the Richland County housing

market and how it can be strengthened going forward. Drawing on public and secondary data,

interviews and focus groups with stakeholders, and market research, it presents a comprehensive

picture of Richland County’s current housing market, identifies housing needs and opportunities

for housing development, and presents strategies for the county to pursue to strengthen its

housing market.

The document contains five chapters. These include…

• The

Baseline Housing Inventory Report provides a review of housing plans, programs,

stakeholders, and collaborations in Richland County. It also analyzes housing services

available to Richland County residents while identifying areas where service provision could

be improved through collaboration or technical assistance.

• The

Housing Data Inventory Report presents a housing data inventory for Richland County.

Using a node-based interpolation method, it presents Census and other data for each of the

analysis nodes in the county.

• The

Market Analysis includes information on permitting activity and the county’s real estate

market, including analysis of home sales within each node. It also identifies opportunities for

market-rate, attainable, and affordable housing development.

• The

Housing Needs Assessment analyzes land use and zoning across the county, and

project’s the county’s housing needs in terms of owner-occupied, rental, and affordable units

through 2032. It also includes an analysis of the economic impacts of developing housing as

well as identifying the top three housing needs for the county going forward.

• Finally, the

Strategy Guide and Action Plan identifies eight strategies that Richland County

stakeholders can pursue to strengthen the county’s development capacity, streamlining

zoning and permitting processes in the county to promote housing development (especially

of attainable housing), and expand the number of housing opportunities available for low-

income and vulnerable populations. For each strategy, the chapter both identifies key action

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

x January 23, 2023

steps for the county to pursue and presents examples that other communities have developed

in pursuing similar strategies.

Two aspects of this report make it especially unique relative to other county-wide housing market

analysis. The first is that we’ve divided the analysis into three broad market segments: market-

rate, attainable, and affordable. To summarize:

•

Affordable housing comprises housing for households earning below 80 percent of the Area

Media Income (AMI). For 2022 is $41,550 for a single-person household and $59,300 for a

family of four in Richland County. While not all households earning below those amounts

reside in subsidized housing, 80% of AMI is typically the limit for most subsidized housing

programs. Within this category, HUD has developed several additional housing categories,

including ‘Extremely low-income’ (below 30% of AMI), ‘Very low-income’ (below 50% of AMI),

and Low-income (below 80% of AMI).

•

Attainable housing comprises housing for households earning between 80–120 percent of

Area Median Income. Per HUD’s 2022 income limits, this comprises single person households

earning between $41,550–$62,280 a year and four-person households earning between

$59,300–$88,920 a year. Households in this income category earn too much to qualify for

federal rental assistance, and they are often in the market for ‘starter’ or entry-level homes.

•

Market-rate housing comprises housing for households earning above 120 percent of area

median income, or over $62,280 for a single-person household or $88,920 for a family of four.

Households in this income category are seeking a higher-end housing product with amenities

like more square footage, a larger yard, pool, finished basement, or other comforts. The

majority of households seeking market-rate housing have two incomes.

The second unique aspect of this project is that it divides Richland County into seven analysis

nodes: Bellville, Lexington, Mansfield, Ontario, Shelby, and the urban

1

and rural

2

townships.

Where available and appropriate, we’ve divided the analysis in this report by nodes.

Key findings identified in this report, organized by chapter, include the following.

Baseline Housing Initiatives Report

A SWOT Analysis of Richland County’s housing market shows both incredible pride in the

community and many emerging opportunities for housing development. Drawing on a

series of focus groups with local stakeholders, the Community Science team identified several

1

These include Madison, Mifflin, Springfield, and Washington Townships

2

Bellville, Bloominggrove, Butler, Cass, Franklin, Jackson, Monroe, Perry, Plymouth, Sandusky, Sharon,

Troy, Weller, and Worthington Townships

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

xi January 23, 2023

strengths and opportunities in Richland County’s housing market. Strengths included incredible

pride in the community among stakeholders and the diversity of the different communities across

Richland County. Both recent investments in the county and the recent reversal of its decades-

long population decline also have contributed to a sense of momentum, which fuels opportunities

for housing development. Other opportunities for housing development residential development

to capture commuters to the Intel facility currently under construction in Licking County, as well

as the large amount of vacant land in Mansfield’s inner-city neighborhoods that is available for

development.

Analysis of housing services offered shows that most services are available in Richland

County, and that there are few redundancies in service delivery. As noted by one

stakeholder, Richland County has “everything you need, but nothing more.” Nevertheless, the

analysis of current housing services noted two gaps in service delivery: transportation assistance

and housing assistance for low- to moderate-income households (e.g., those who earn too much

to qualify for certain programs but who still face significant housing needs). This latter group

comprises many older households who reside in older homes in the county with significant

maintenance needs. The services analysis also identified two redundancies in service delivery, in

rental assistance and utility assistance. However, those redundancies largely seem to be a product

of agencies utilizing different funding sources, though the report calls for greater collaboration in

delivering those services.

A lack of housing development capacity in the county fuels the weaknesses to the county’s

housing market as well as the county’s pressing technical assistance needs. Focus group

participants identified the county’s lack of development, construction, architecture, and contractor

expertise as the greatest weakness in the county’s housing market. At the affordable housing

level, the lack of a Community Housing Development Organization (CHDO) was also identified as

a key weakness to developing affordable housing, and for attainable housing, the lack of expertise

in rehabilitating older housing was also cited as such. For these reasons, the two primary technical

assistance needs identified for the county included (i) affordable housing financing and

development and (ii) development, contracting, and architecture services.

Housing Inventory Report

In terms of demographics, Richland County has a rapidly aging population that has

important impacts on housing development. Per recent Census data, 20 percent of the

county’s population are currently seniors, and another 14 percent are near seniors (age 55–64).

In the next 10 years, the county will need to expand the number of senior-friendly units available

so that these residents can age in place, such as condos or senior-only communities. Aging in

place may also require an expansion of home modification efforts, especially for seniors living in

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

xii January 23, 2023

the county’s older housing stock (which tends to not be accessible, with stairs and often only one

bathroom on the second floor).

Census data confirm that Richland County has an older housing stock, and that very few

units have been constructed within the last 20 years. About 20 percent of the county’s

housing units were built before 1939, and another 55 percent were constructed between 1940–

1979. Certain nodes, though, have a much older housing stock—in Shelby, for instance, nearly a

third of housing units were built before 1939, and the comparable figure in Mansfield is 25

percent. In site visits to the county and in conversations with stakeholders, many of these older

homes have not been substantially rehabbed, and many pose safety risks to their occupants (e.g.,

knob and tube wiring, asbestos, lead paint).

Relatedly, only about 9.5 percent of the county’s housing stock has been built in the last 20 years,

and very few units (well under 1,000) have been built in the past 10 years. This lack of new

construction has negative impacts on local development capacity (as people leave for ‘hotter’

housing markets), the tax base (as wealthier households desiring new housing locate to other

communities), and economic development activity (as companies looking to locate to the county

get the sense that the county is not growing or developing).

Richland County contains a large stock of mobile homes, which has unique impacts on the

county’s housing market. Per Census data, there are over 2,000 mobile homes in Richland

County. In several of the nodes—especially the urban and rural townships—mobile homes

comprise over 5 percent of their housing stocks, respectively. On the one hand, they are a

valuable source of affordable housing, and their residents typically appreciate the independence

that comes from owning the unit that one lives in. On the other hand, mobile homeowners are

vulnerable to changes in park ownership, as moving their homes entails a substantial cost (in the

thousands of dollars) that many cannot afford. Mobile homes, especially older ones, are also more

vulnerable to destruction due to fires or tornadoes.

Despite the low cost of rental housing in Richland County, many of the county’s renters

are cost burdened. While most rental opportunities in the county have contract rents under $700

a month (which is well below national figures), at least 40 percent of renters in each node (except

for Bellville) are cost-burdened—meaning they spend over 30 percent of their income toward rent

and utilities. Additionally, over one-in-five renters in the county spend over 50 percent of their

income toward rent and utilities. Looking across the nodes, both Mansfield and Shelby have the

highest rates of cost-burdened renters. These high rates of cost-burdened renters suggests the

need for additional affordable housing in the county, as well as additional rent supports (such as

housing vouchers).

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

xiii January 23, 2023

Market Analysis

Permitting in the county declined dramatically during the Great Recession and has only

begun to recover, though it remains well below pre-2007 trends. From 2002–2007, there

were at least 100 permits filed in Richland County in every year,

3

and in several of those years

there were over 200 permits filed. However, since then, there have yet to be 100 permits filed in

any year in Richland County (excluding Mansfield). In recent years, though, the number of permits

filed has begun to approach 100, and it may exceed this figure in 2022 or 2023. In Mansfield,

permitting activity has increased in recent years, with 22 permits filed in 2020 and 20 filed in

2021 (compared to no more than 10 permits filed in any year from 2011–2019).

The majority of new permits filed in the last 10 years have been for single-family homes

in unincorporated parts of the county. Since 2012, nearly 60 percent of all new single family

permits have been filed in the rural townships, and an additional 22 percent have been filed in

the urban townships. In terms of multifamily permitting in the last 10 years, nearly all of these

permits have been filed in Ontario, and the maximum number filed in any given year since 2016

is 13 permits (in 2018).

Richland County’s market trends suggest a tight housing market that is pushing prices

higher. While units sold have been relatively flat the last five years (averaging about 125–150

homes sold every month), average prices have increased dramatically—from $100,000 in January

2017 to nearly $175,000 today. Given how little housing has been built in the county over that

period, this suggests dramatic appreciation of existing inventory. This is further confirmed by the

days-to-pending data—over the last 3.5 years, this has gone from a median of 30 days to a

median of less than 10 days.

While house prices have increased throughout the county, they have had different

impacts in the markets in each node. For lower-cost nodes like Mansfield and Shelby, the

proportion of houses selling for under $100,000 has decreased, though both nodes still appear

to contain many opportunities for attainable homeownership. For more expensive nodes like

Ontario and Lexington, the availability of attainable homeownership opportunities has almost

completely evaporated as sales prices now increasingly push into the $300,000+ range.

Richland County’s most pressing short- to mid-term housing needs include around the

development of attainable housing, housing for seniors, and affordable housing. Key

market gaps identified include:

3

Due to data limitations, we do not have permitting data for Mansfield before 2011, so the findings in

this paragraph all pertain to portions of the county outside of Mansfield. In addition, we do not have

permitting data for Bellville in any year.

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

xiv January 23, 2023

• Development of new owners-occupied housing in the upper attainable and lower market-rate

categories (roughly the $150,000–$225,000 price range). Given current construction costs, it

is unfeasible to develop new, unsubsidized, stick-built (i.e., non-modular) single family home

construction at this price point. Thus, the county should prioritize the development of condos,

zero-lot line homes, townhomes, and small multifamily (duplexes, triplexes, and quadplexes)

housing.

• Rehabilitation of older housing into affordable and attainable homeownership opportunities.

• New market-rate housing construction specifically targeted toward seniors.

• Market-rate rental housing with contemporary amenities.

• Affordable housing, especially units targeted those who are currently unhoused or at risk of

becoming unhoused.

Housing Needs Assessment

Note: In addition to this report, we have produced a

Housing Needs Assessment for each of the

seven nodes.

Overall, zoning in Richland County is complicated, and makes the development of

attainable housing difficult. Nearly every jurisdiction in the county has its own zoning code (the

exception being some of the rural townships), and each code has its own mix of districts with

their own by-right and conditional uses, parameters (setbacks and minimum lot sizes), and

restrictions. Furthermore, the zoning map of nearly every node is heavily weighted toward R1

(single family only) zones, making attainable housing development challenging. Also making

attainable housing development challenging is that the county’s zoning codes require relatively

large lots, even for higher-density residential uses, and are very restrictive on multifamily housing

development. As we note in the report, jurisdictions in the county may consider adopting Shelby’s

small lot R1A and R2A zoning districts to promote the development of attainable housing.

Based on trends in the past 10 years, we project that Richland County will need to add

2,475 owner-occupied units and 3,364 renter-occupied units by 2032 to sustain its

growth.

Breaking down these housing needs by age group, growth in Richland County

households will be concentrated in two areas. The first will be senior households, and this is

where the majority of households growth in Richland County will occur. The second area of growth

is in younger adult households, commonly known as ‘Gen Z.’ The growth in these households

will primarily occur in the rental market, but there will also be some growth in the number of

homeowners in this age cohort as well.

In addition to constructing new units, the county will need to prioritize preventing older

units from becoming dilapidated and bringing currently vacant units back online. Based

on data from 2010–2021, we project that Richland County will lose approximately 1,700 housing

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

xv January 23, 2023

units to dilapidation by 2032. However, investing in a county-wide rehabilitation program could

prevent some of those units from exiting the housing stock. In addition, the US Postal Service

currently estimates that there are approximately 2,500 vacant units in Richland County. Returning

half of those units to a habitable state would address nearly 20 percent of the county’s housing

needs in the next 10 years.

We project that Richland County will need approximately 2,700 additional affordable

rental units by 2032, though the county will also have a surplus of affordable owner-

occupied units at that time.

Using HUD data, we project that a plurality of those affordable

units will need to be one-bedroom (1,255 units), with additional 3+ bedroom (969) and 2-

bedroom (463) units needed. All of these units will need to be affordable to households earning

less than $20,000 annually. However, by 2032, we project that the county will have a surplus of

over 5,000 deeply-affordable owner-occupied units (those affordable to those earning less than

$20,000). While many of these units likely require substantial rehabilitation work, this is a unique

opportunity for the county to move lower-income households into homeownership.

Meeting the county’s housing needs would have strong economic development impacts.

Using a formula developed by the National Association of Homebuilders, we estimate that

constructing 100 new single-family homes would contribute to nearly $28.7 million in the local

economy in the first year and will provide an additional $4 million in local income annually, in

addition to supporting 69 local jobs following construction. Similarly, developing 100 near rental

apartments would provide over $11.5 million in local income in the first year and over $2.5 million

in local income annually going forward.

Strategy Guide and Action Plan

Strategies related to improving funding and capacity for housing development center on

both developing local capacity and Richland County ‘on the radar’ of out-of-town

developers.

Specific strategies identified include promoting the county to outside developers

through a website and Requests for Proposals (RFPs) for specific sites; building the capacity of a

local organization to serve as a CHDO and identifying capacity to facilitate downtown housing

development and rehabilitation of distressed housing. We also recommend that county

stakeholders create and fund a ‘Housing Coordinator’ position to coordinate housing efforts both

within this topic and other topics.

Permitting and zoning reforms can promote housing development throughout the county,

especially the development of attainable housing. Stakeholders and developers have

consistently cited codes and permits as a barrier to new housing development in the county, and

aligning and streamlining permitting processes both within and across jurisdictions—such as by

creating a ‘one stop shop’—can ameliorate those challenges. Additionally, aligning and simplifying

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

xvi January 23, 2023

zoning both within and across jurisdictions can reduce some of the complexity associated with

development in the county, as developers must learn the ins and outs of each jurisdiction’s zoning

code. Finally, as noted in the housing needs assessments, the zoning maps and codes of each

jurisdiction are weighted toward single-family, large lot zoning. Adopting small lot zoning and

simplifying the rules for multifamily development can promote the development of attainable and

affordable housing.

To increase the availability of affordable and transitional housing, stakeholders should

prioritize opportunities for affordable homeownership and increasing housing for

vulnerable populations.

As noted in the Housing Needs Assessment, Richland County has a

surplus of affordable owner-occupied units, and local stakeholders can leverage that surplus to

create homeownership opportunities for low-income households. To do so, though, they will need

to expand the county’s capacity to rehabilitate those homes and to provide services and

homeownership education to low-income households, as many will be first-time buyers.

Expanding the number of units to vulnerable populations (such as the unhoused and those leaving

the justice system) will require investments in local service providers as well as innovative

partnerships between service providers and other groups (such as Metro Housing).

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

1 January 23, 2023

Introduction

This is an exciting time for the housing market in Richland County, Ohio. Through leadership,

creative partners, and new investments, the county is on a path to revitalization following decades

of job losses and declining population.

In partnership with the Housing Development Steering Committee, Community Science has

developed this

Housing Needs Assessment and Action Plan

to benchmark Richland County’s

current housing market, understand its current and project housing needs, and develop strategies

for county stakeholders to meet those needs in the coming year.

The plan is organized into five chapters. These include:

• The Baseline Housing Inventory Report provides a review of housing plans, programs,

stakeholders, and collaborations in Richland County. It also analyzes housing services

available to Richland County residents while identifying areas where service provision could

be improved through collaboration or technical assistance.

• The Housing Data Inventory Report presents a housing data inventory for Richland

County. Using a node-based interpolation method, it presents Census and other data for each

of the analysis nodes in the county. The chapter also includes a series of static maps showing

demographic and housing characteristics across the county’s Census tracts.

• The Market Analysis includes information on permitting activity and the county’s real estate

market, including analysis of home sales within each node. It also identifies opportunities for

market-rate, attainable, and affordable housing development.

• The Housing Needs Assessment analyzes land use and zoning across the county, and

project’s the county’s housing needs in terms of owner-occupied, rental, and affordable units

through 2032. It also includes an analysis of the economic impacts of developing housing as

well as identifying the top three housing needs for the county going forward.

• Finally, the Strategy Guide and Action Plan identifies eight strategies that Richland County

stakeholders can pursue to strengthen the county’s development capacity, streamlining

zoning and permitting processes in the county to promote housing development (especially

of attainable housing), and expand the number of housing opportunities available for low-

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

2 January 23, 2023

income and vulnerable populations. For each strategy, the chapter both identifies key action

steps for the county to pursue and presents examples that other communities have developed

in pursuing similar strategies.

Types of Housing Considered

Given the breadth of the housing market and the desire of community stakeholders for this report

to address the totality of Richland County’s housing market, the Community Science team divided

Richland County’s housing market into three segments: affordable, attainable, and market-rate.

These include:

•

Affordable housing comprises housing for households earning below 80 percent of the Area

Median Income (AMI). For 2022, the 80 percent AMI threshold was $41,550 for a single-

person household and $59,300 for a family of four in Richland County. Many households in

this range qualify for federally subsidized housing, though relatively few receive it.

•

Attainable housing comprises housing for households earning between 80–120 percent of

AMI. Using 2022 income limits, this single person households earning between $41,550–

$62,280 a year and four-person households earning between $59,300–$88,920 a year. These

households are typically interested in ‘starter’ or entry-level homes, and can generally afford

homes priced under $200,000.

•

Market-rate housing comprises housing for households earning above 120 percent of area

median income, or over $62,280 for a single-person household or $88,920 for a family of four.

Households seeking market-rate housing are typically seeking a higher-end housing product

and can generally afford houses priced over $200,000.

We provide greater detail on these types of housing, and the household types associated with

each, in Chapter 1.

Nodes

Another characteristic which makes this

Housing Needs Assessment

unique is that it not only

considers Richland County as a whole, but also analyzes housing market conditions in specific

‘nodes’ of Richland County. These nodes include the five largest municipalities in Richland County,

as well as two classifications for the remainder of the county (including its townships and relatively

small municipalities of Butler, Shiloh, and Plymouth). These nodes include:

• City of Mansfield

• City of Ontario

• City of Shelby

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

3 January 23, 2023

• Village of Lexington

• Village of Bellville

• Urban townships of Richland County (Madison, Mifflin, Springfield, and Washington)

• Rural townships of Richland County (Plymouth, Cass, Blooming Grove, Butler, Sharon,

Jackson, Franklin, Sandusky, Troy, Monroe, Perry, Bellville, Weller, Worthington)

We provide greater detail on these nodes, as well as a map, in Chapter 1.

Data Sources

In developing this document, the Community Science team has relied on the quantitative and

qualitative analysis of both primary and secondary data. Key data sources used include:

• Qualitative data

o Three focus groups, held in April and May 2022, with Richland County stakeholders

o Semi-structured interviews with approximately 40 stakeholders regarding Richland

County’s housing conditions

o Interviews with approximately five Mansfield Metropolitan Housing Authority clients

regarding their experiences seeking affordable housing

o Feedback gathered through three community meetings with Richland County housing

stakeholders (approximately 50 stakeholders in attendance at each meeting)

o Three strategy sessions (funding and capacity, development, and affordable and

transitional housing, respectively) with approximately 10 stakeholders attending each

session.

• Quantitative data

o American Community Survey demographic and housing estimates

o Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy (CHAS) data

o Fannie Mae’s Housing Price Index

o Historic housing counts (HHUUD10)

o Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) mortgage data

o Ohio Housing Finance Agency’s USR (Urban-Suburban-Rural) indicators data

o Ohio Association of Realtors market sales data

o Richland County Auditor sales data

o Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics commuting and industry data

o HMIS (Homeless Management Information System) data

o Ohio Department of Development population projections

o Opportunity Insight’s Opportunity Atlas

o Permitting data from Richland County and the City of Mansfield

o Zillow Research housing data

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

4 January 23, 2023

These data sources are discussed in greater detail when utilized or analyzed throughout this

report.

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

5 January 23, 2023

Chapter 1: Baseline Housing Initiatives Report

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

6 January 23, 2023

Baseline Housing Initiatives Report

Introduction

This Baseline Housing Initiatives Report

provides a review of housing plans, programs,

stakeholders, and collaborations in Richland County. It also analyzes housing services available

to Richland County residents while identifying areas where service provision could be improved

through collaboration or technical assistance.

Throughout this chapter and the broader

Housing Needs Assessment and Action Plan

, we’ll refer

to three specific types of housing: affordable, attainable, and market-rate. We have illustrated

these housing types in Exhibit 1.

4

To summarize:

Affordable housing comprises housing for households earning below 80 percent of the Area

Median Income (AMI). For 2022, the 80 percent AMI threshold was $41,550 for a single-person

household and $59,300 for a family of four in Richland County. While not all households earning

below those amounts reside in subsidized housing, 80% of AMI is typically the limit for most

subsidized housing programs. Within this category, HUD has developed several additional housing

categories, including ‘Extremely low-income’ (below 30% of AMI), ‘Very low-income’ (below 50%

of AMI), and ‘Low-income’ (below 80% of AMI).

The types of households seeking affordable housing are incredibly varied. At the lowest income

levels, they include households unable to work who rely solely on SSI disability income. These

also include households in food service and hospitality occupations who earn Ohio’s minimum

wage of $9.30 an hour or slightly above, and service-sector workers like those in office and

administrative support.

Attainable housing comprises housing for households earning between 80–120 percent of Area

Median Income. Per HUD’s 2022 income limits, this comprises single person households earning

between $41,550–$62,280 a year and four-person households earning between $59,300–$88,920

4

Occupation wage data in those tables are sourced from Indeed.com and from local hiring materials.

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

7 January 23, 2023

a year. Households in this income category earn too much to qualify for federal rental assistance

and are often in the market for ‘starter’ or entry-level homes.

The types of households seeking attainable housing include a single person working in

transportation, law enforcement, or firefighting. They also includes dual-income households who,

individually, would be seeking ‘affordable’ housing but who together would be seeking attainable

housing (e.g., an administrative assistant and a food service manager).

Finally,

market-rate housing comprises housing for households earning above 120 percent of

area median income, or over $62,280 for a single-person household or $88,920 for a family of

four. Households in this income category are seeking a higher-end housing product with amenities

like more square footage, a larger yard, pool, finished basement, or other comforts. The majority

of households seeking market-rate housing have two incomes or a single high-paying job like in

the engineering field. These households also include managers at firms who have worked their

way into a higher-paying position.

The remainder of this report includes the following topics:

• The following section summarizes a review of existing housing and related plans for Richland

County. It includes a discussion identifying stakeholders, programs and initiatives, and

challenges and successes identified in those plans.

• Next, the report discusses stakeholder feedback from the focus groups and kick-off meeting

held in Ontario on April 29, 2022. The focus group analysis employs a SWOT (Strengths,

Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) framework to summarize feedback. The kick-off

meeting feedback presents summaries from responses to questions posed during the meeting

using the Mentimeter platform.

• The report then analyzes housing services and programs offered in the county. It presents a

summary of current services before analyzing those services in terms of (i) gaps in service

delivery, (ii) technical assistance needs, (iii) redundancies in services, and (iv) opportunities

for collaboration.

• Finally, the report concludes by identifying nodes for future analysis.

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

8 January 23, 2023

Exhibit 1: Summary of housing categories

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

9 January 23, 2023

Plan Review

The first step in developing this report was to review various housing-related plans that have

been completed for Richland County and its municipalities. The goal of this review was to better

acquaint the Community Science team with stakeholders, programs and initiatives, challenges,

successes, and goals related to Richland County’s housing market. In addition to reviewing over

a dozen plans for Richland County, the Community Science team selected several plans for deeper

analysis. These include:

• City of Mansfield 2020 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing

• Richland County 2019 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing

• Mansfield Rising Downtown Investment Plan 2019

• North End Community Improvement Corporation (NECIC) 2017 Economic Development Plan

• Mansfield West End Neighborhood Plan 2020

• Downtown Mansfield Housing Plan

• Lexington 2035 Comprehensive Plan

• City of Shelby Strategic Plan 2010–2030

• NECIC Senior Housing Development Feasibility Analysis (published April 2019)

Programs, Initiatives, and Opportunities

The plan analysis identified several programs, initiatives, and opportunities throughout the

county. These include:

• The Richland County Land Bank has acquired many blighted and vacant properties throughout

the county but especially in the neighborhoods surrounding downtown Mansfield. This has

left many of these neighborhoods with a considerable amount of developable land. Local

stakeholders can take advantage of different funding streams to develop affordable and

attainable housing on those lots.

• Given the age of the county’s housing stock, many of the county’s homes (especially in

Mansfield, Shelby, and Bellville) are of a historic character and could appeal to younger,

‘millennial’ homebuyers who are interested in rehabbing them (if they have not been

maintained).

• In terms of development, several studies have identified types of development that are

economically feasible. For downtown Mansfield, there exists a market for small (11-unit)

market-rate apartments. Demand for these apartments would be fueled by the growth of

higher-income households in the community. In Ontario, creating a mixed-use town center

district near the OSU-Mansfield and North Central Community College area could facilitate

vibrant development.

• Richland County communities outside of Mansfield and Ontario also have a number of

amenities that can be leveraged to support additional housing development. Lexington’s parks

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

10 January 23, 2023

and recreation opportunities are an asset for the community to promote in securing additional

residential, commercial, and industrial development.

• The Mansfield Rising Initiative, in partnership with Downtown Mansfield, Inc. and other local

stakeholders, has successfully reinvigorated many of the commercial spaces in downtown

Mansfield. The Richland County Foundation has recently pledged money to help return the

spaces above downtown Mansfield’s storefronts to residential use.

Challenges

Analysis of these plans identified these cross-cutting challenges across Richland County. These

include:

• While recently reversed, the county experienced population loss for several decades and was

hit hard by the foreclosure crisis in the late 2000s. This has left the county with a large number

of abandoned homes. While the Land Bank and city governments have aggressively

demolished a large number of these abandoned homes, many still remain.

• Much of the county’s housing stock is quite old and, in addition to lacking modern amenities,

is also not accessible to elderly or disabled residents. This is especially a concern in the North

End of Mansfield, where many of the houses have obsolete systems, are in poor condition,

and have multiple stories (and thus not accessible to the elderly/disabled without

modifications). There are also concerns that many of these older properties suffer from lead

paint contamination.

• Overall, there are concerns about the quality of rental housing in Richland County, especially

in Mansfield. Many rental properties, while affordable, are in a significantly degraded condition

and contribute to a sense of blight in certain neighborhoods. Landlords for these properties

are often located out of state and are unwilling to engage in local planning efforts.

• Despite the county’s seemingly affordable housing stock, wages in the area are often not

enough for households to reside in the county without being cost-burdened. This results in

many households residing in sub-standard housing that, nevertheless, they can afford.

• Many of the smaller communities in the county struggle to attract commercial businesses to

their communities. These local businesses are crucial for improving livability and enticing

residential development.

• The topography of Richland County makes many lots undevelopable. Flooding is a concern in

many parts of the county, especially in Shelby. The topography also increases the price of

providing utilities, especially sewer lines, to undeveloped lots. This, when combined with the

relatively lower cost of housing in the county, makes housing development more difficult, as

developers are unable to recoup the cost of providing utilities by increasing the pricing of

housing. It also points to the need for innovative partnerships for providing utilities for new

developments.

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

11 January 23, 2023

Stakeholder Feedback

In developing the

Baseline Housing Initiatives Report

, the Community Science team provided

three opportunities for community input. First, we held a series of three focus groups in mid-April

2022, with approximately 20 community stakeholders. Second, we hosted a kick-off meeting in

Ontario on April 29 that was attended by over 40 stakeholders. In addition to these opportunities

for community input, the Community Science team also conducted one-on-one interviews with

both stakeholders and service providers. Results from these interviews are summarized in the

following section.

Focus Groups

The Community Science team held three focus groups with local stakeholders in mid-April 2022.

Invitations to these focus groups were included in the invite to the kick-off meeting and interested

individuals could sign up to participate. In total, 17 individuals participated in these focus groups,

including representatives from

• Local government, including both elected officials and civil servants;

• Economic development;

• Real estate and property investing;

• Social service providers;

• Key local ‘anchor’ institutions.

We have summarized focus group feedback below using the SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses,

Opportunities, and Threats) paradigm below.

Community Strengths

As expected, focus group participants expressed an incredible amount of pride about Richland

County. One described it as “amazingly livable,” while another noted that it has “everything you

need, but nothing more.” Participants were prideful not only of the community they called home,

but of the entire county as a whole. There was a palpable sense that the county had weathered

the storm of economic disinvestment and that brighter days are ahead.

Another strength of Richland County is the diversity of its communities, which was highlighted

across all focus groups. There are both extremely rural parts of the county, as well as quite urban

parts of Mansfield. The county also has several small towns which offer unique living

environments somewhere between rurality and urbanity. This diversity of communities,

particularly the presence of a larger city like Mansfield, sets Richland County apart from many of

its surrounding communities and is an asset to be leveraged.

Finally, there was a sense of positive momentum in the county resulting from both ongoing

investments and, for the first time in decades, increased population based on the most recent

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

12 January 23, 2023

Census. This positive momentum has changed the mindset of many stakeholders from being a

‘shrinking’ community to a ‘growing’ community.

Community Weaknesses

The greatest challenge identified across all three focus groups was the lack of housing supply

across the affordability spectrum—affordable, attainable, and market rate.

At the

affordable housing level, stakeholders identified that while a substantial number of units

exist (especially in Mansfield), many are lower quality and landlords are often unwilling to rent to

individuals with housing vouchers or with incomplete or negative rental histories. Demand for

these units is often high as well, allowing landlords to be ‘choosy’ with who they rent to. Many

property owners are not located in the area, making them unwilling to engage with local housing

efforts. Some participants noted that ‘tiny homes’ could be an attractive way to create new

affordable housing stock, but it appears that current zoning regulations preclude their

development.

Related to the lack of affordable housing supply is the county’s lack of a Community Housing

Development Organization, or CHDO,

5

though it has had them in the past (including the North

End Community Improvement Collaborative). Lacking a CHDO means that Richland County misses

out on a portion of the state’s HOME funds that are set aside to help CHDOs develop affordable

housing. High-capacity CHDOs can also serve as both (i) experts in affordable housing

development and navigating the guidelines needed to develop affordable housing; and (ii)

conveners of stakeholders to support high-quality affordable housing development (e.g.,

developers, contractors, government officials, service providers, etc.).

Another weakness related to affordable housing is the supply of deeply affordable, rapid

rehousing, supportive housing for those currently unhoused or at risk of becoming unhoused.

While the county has two shelter facilities (Harmony House and The DV Shelter) and the Mental

Health Board, Catalyst, and the Pediatric Development Center all either own or operate supportive

housing facilities, there is a general recognition that (i) the county lacks a sufficient number of

these units; and that (ii) better coordination between these agencies (in addition to other

stakeholders, like Metro Housing) is needed. There also appears to exist a need for additional

staffing, technical assistance, and capacity building among service providers for the unhoused in

the county (discussed in greater detail later in this report).

5

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

13 January 23, 2023

At the

attainable housing level, participants noted that current construction costs make

developing new housing product at this level virtually unfeasible without some type of subsidy.

6

Given the income restrictions on many different types of housing subsidy—as well as pressing

need to dedicate funding to create affordable housing—there are few opportunities to subsidize

this type of development.

One way to develop attainable housing would be to renovate the older housing stock in the county

into an attainably-priced housing product. Yet lead, asbestos, accessibility, and other issues

typical of older housing stock (e.g., knob and tube wiring) often make renovations financially

prohibitive, and many of the funds available for home renovations are limited to special

populations (e.g., the elderly and/or those with very low incomes).

At the

market rate housing level, lack of local development, construction, and contractor

expertise were cited at the greatest barrier to expanding the housing stock. Given the region’s

multi-decade period of population decline—and the county’s high rate of vacant housing following

the Great Recession—many developers and contractors left for faster-growing and more

expensive housing markets, including Columbus.

Beyond the lack of contractors and development expertise, another identified weakness for

market-rate housing development was the county’s lack of development-ready land. While

Richland County certainly has ample open space that could be developed, according to focus

participants many hurdles exist to developing that land. One is utilities (or lack thereof),

particularly sewer lines, to which many undeveloped properties lack access. Local governments

have often not extended this access for housing development and given both (i) the hilly terrain

of much of Richland County and (ii) the county’s overall lower-priced housing, having to provide

sewer access may make many housing developments economically unfeasible.

A third weakness identified was the bureaucracy associated with developing market-rate housing

across Richland County. This was noted across all focus groups, with the county’s codes and

permitting process (managed through a multi-county consortium) mentioned as being particularly

onerous and time-consuming. Additionally, many focus group participants believed that the

zoning for many areas does not reflect the most appropriate and most economically feasible type

of development.

The lack of new market-rate development inhibits the formation of housing chains, thus

exacerbating shortages of attainable and (non-subsidized) affordable housing. A housing chain

6

This is not a challenge unique to Richland County, and is instead faced by communities across the U.S.;

see

https://www.realtor.com/news/trends/death-of-the-starter-home-where-have-all-the-small-houses-

gone/. A key focus of this report will be to identify sustainable models for developing attainable housing

through new construction and rehabilitation of existing properties.

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

14 January 23, 2023

occurs when a new, market-rate housing unit becomes available and is occupied by a local

resident. The unit that the resident leaves can then ‘filter’ down to a household at a lower income

level. Thus, lack of development of market-rate housing negatively impacts the stock of attainable

and affordable housing.

Community Opportunities

Focus group stakeholders identified several opportunities to create shared prosperity in the

Richland County housing market. Overall, there was a sense of momentum in the county creating

opportunities that have not been seen in decades, if ever. Specific projects mentioned include the

North End community center in Mansfield, work to improve flooding throughout the county, as

well as a pipeline of business attraction and expansion projects.

However, by far the most-cited opportunity for Richland County was the Intel facility that will be

opening in Licking County, just outside Columbus, in the coming years.

7

While the facility is

expected to employ approximately 3,000 workers, there will likely be multiples more workers

drawn to the area to work for suppliers and for industries supporting employees at the facility

(education, hospitality, etc.).

Another opportunity identified was that, due to aggressive demolitions of vacant and abandoned

property, there is a substantial amount of vacant land in Mansfield’s inner-city neighborhoods

available for development. Many of these parcels are owned by the Richland County Land Bank,

which can strategically divest these properties to support affordable, attainable, and market-rate

housing development.

Community Threats

While Richland County is currently enjoying a plethora of opportunities, with those come threats

to creating shared prosperity for current and future generations. Broadly, these threats often fell

under the category of fears that the county will fail to “seize the moment” and capitalize on the

opportunities that present themselves.

A commonly expressed sentiment across the focus groups was that stakeholders and leadership

need to think creatively and ‘outside the box’ to address the area’s housing needs. For many

housing development opportunities, Richland County is in competition—for better or worse—with

surrounding counties which, while lacking some of the amenities that Richland enjoys, can also

offer abundant land for development.

7

https://www.dispatch.com/story/business/information-technology/2022/01/14/intel-near-columbus-

ohio-what-know-site-factory-project/6514569001/

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

15 January 23, 2023

Related to this threat was the need for dynamic leadership, which was identified as a need across

multiple focus groups. While the community’s leaders have initiated a successful effort in setting

up Richland County to meet the present opportunities described in the previous section, there

was a sense that more individuals from younger generations, and those who relocated to Richland

County as adults, should be encouraged to seek elected office.

Ultimately, failing to capitalize on the current moment will mean that Richland County’s

opportunities will flow to other, surrounding counties. Several of these counties are arguably

ahead of the curve in terms of planning for housing growth, with market-rate development

occurring in Galion’s downtown and high-end rental units in Ashland.

Kick-off Meeting

With assistance from the Housing Development Steering Committee, the Community Science

team hosted a kick-off meeting for local stakeholders at the Area Office on Aging on April 29,

2022. Over 40 stakeholders—representing government, development, housing service providers,

and other interested agencies—attended the kick-off meeting. Following a short presentation

about the project, the Community Science team collected participant feedback through the

Mentimeter platform.

The second feedback question asked, “What do you see as the greatest housing need in your

community?” Individuals could provide up to three responses. A total of 40 respondents answered

this question, recording 52 total responses. These responses are categorized in Exhibit 2 (note

that responses could ‘fit’ into multiple categories, so the sum is greater than 52).

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

16 January 23, 2023

Exhibit 2: Responses to 'What is the Greatest Housing Need in Your Community?"

The greatest housing need identified was more affordable housing, which was noted by half of

all respondents. Particularly noteworthy responses here include:

• Clean, safe housing available to home buyers and renters of all incomes in all our communities

• More affordable inventory

• Safe, affordable housing to meet the needs of the current and growing population mix

Closely behind—and closely related—was the need for more housing stock in general, including

affordable, attainable, and market-rate units. Additional respondents touched on improving the

quality of housing available in Richland County (nine responses); expanding opportunities for

homeownership (eight responses), seniors (six responses), and renters (three responses); and

expanding the pool of developers and contractors in Richland County (four responses). Exemplary

comments for these categories include:

• Need new housing stock ranging from apartments, affordable housing, “starter” houses, and

custom houses

• Local contractors for construction and repair

• Fix up or replace dilapidated housing

• Homes that people can buy someday, not just to rent forever

• Updated, new construction at affordable pricing

Richland County Housing Needs and Action Plan

17 January 23, 2023

The third and final feedback question asked respondents “What do you see as the housing-related

capacity that could be improved in Richland County?” Thirty-two participants provided responses

to this question, which are summarized in Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3: Responses to "What do you see as the housing-related capacity that could be improved

in Richland County?"

Related to the previous question, the two most-common responses relate to capacity to develop

housing and attracting more developers and/or contractors to Richland County. Within the

‘housing development’ category, responses include both general capacity and the capacity to

achieve certain types of development, such as:

• Need more homes developed (general)

• Collaborative development (general)

• Start building on land bank property (specific)

• Conversion of downtown older buildings into condos (specific)

• More sustainable, energy-efficient homes/rehabs (specific)

Less frequent but still noteworthy responses to this question include expanding financing

expertise (six responses), improving property management capacity (four responses), and

streamlining bureaucracy and permitting (three responses). Within those categories, responses

include:

• Comprehensive knowledge about putting [together] deals and packages to build required

housing (financing)