San Jose State University San Jose State University

SJSU ScholarWorks SJSU ScholarWorks

Faculty Research, Scholarly, and Creative Activity

10-28-2022

Critical Translingual Perspectives on California Multilingual Critical Translingual Perspectives on California Multilingual

Education Policy Education Policy

Eduardo R. Muñoz-Muñoz

San Jose State University

Luis E. Poza

San Jose State University

Allison Briceño

San Jose State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/faculty_rsca

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Eduardo R. Muñoz-Muñoz, Luis E. Poza, and Allison Briceño. "Critical Translingual Perspectives on

California Multilingual Education Policy"

Educational Policy

(2022). https://doi.org/10.1177/

08959048221130342

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in

Faculty Research, Scholarly, and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more

information, please contact scholar[email protected].

1

Critical Translingual Perspectives on California Multilingual Education Policy

Eduardo Muñoz-Muñoz, Luis Poza, Allison Briceño

ABSTRACT

Policies restricting bilingual education have yielded to policy frameworks touting its benefits.

This shift corresponds with evolving lines of debate, focusing now on how bilingual education

can best support racialized bilingual learners (Cervantes-Soon, et al., 2017). One element of this

new debate is the perspective on language underlying curriculum in bilingual programs, with a

focus on translanguaging– normalization of the language practices of bilingual communities and

positing that bilinguals draw from a singular linguistic repertoire (García, 2017; García, Johnson,

& Seltzer, 2017; Leung & Valdés, 2019). This article examines initiatives undertaken in

California between 2010 and 2019 using Critical Policy Analysis (Apple, 2019; Taylor, 1997).

The work highlights that while opportunities for translanguaging have arisen, tensions between

heteroglossic perspectives and the impulses toward standardization and commodification of

language undermine such possibilities, and that notable gaps remain between teacher preparation

frameworks and intended pedagogical practice.

2

Critical Translingual Perspectives on California Multilingual Education Policy

The turn of the 21

st

Century in the U.S. witnessed waves of state and federal policies

constricting bilingual education for students classified as English Learners (EL). In 1998,

California voters approved Proposition 227, advanced largely by billionaire Ron Unz, which

mandated that EL-classified students receive all instruction in English except when families had

completed onerous waiver requirements. Similar initiatives were pushed through in Arizona

(Proposition 203) and Massachusetts (Question 2) in 2000 and 2002, respectively, and another

Unz-backed measure was narrowly defeated in Colorado in 2003. Besides these outright bans,

the widespread mandates for standardized testing carried out mostly in English (and of English,

for EL-classified students) under No Child Left Behind (2001) further pressured schools to

abandon or truncate their bilingual programming. The combined effect of these state and federal

policies was to cut the number of emergent bilingual learners receiving home language

instruction by more than half (Alamillo et al., 2005; Crawford, 2007; Gándara, et al., 2000;

Menken, 2009; Menken & Solorza, 2014).

With ample scholarship demonstrating the harms of these constrictions (Darling-

Hammond, 2007; Matas & Rodríguez, 2014; Ulanoff, 2014), policies restricting bilingual

education have yielded to proliferating frameworks touting its benefits. Nevertheless, allowances

for and promotion of bilingualism and bilingual education have not necessarily been linked to the

civil rights concerns that racially and linguistically minoritized populations brought to the fore in

their initial advocacy for such programs by failing to address broader issues of racialization and

marginalization in political and materialist dimensions (Flores, 2016) or the ideological

predominance of English (Rubio, 2020). This policy shift corresponds with evolving lines of

3

debate moving past whether bilingual education is helpful and rather focusing on how bilingual

education can best support racialized bilingual learners (Cervantes-Soon, et al., 2017).

One element of this new debate is the perspective on language underlying curriculum in

bilingual programs (Leung & Valdés, 2019). Notable scholarship now advances translanguaging

approaches, which we describe further in our theoretical framework, consisting of the

normalization of the language practices of bilingual communities and positing that bilinguals

draw from a singular linguistic repertoire rather than distinct cognitive repertoires for each of

their languages (García, Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017; García & Li, 2014). In this work, we examine

four recent measures advanced in California as part of its reversal of previous suppression of

bilingual education. We rely on a Critical Policy Analysis framework (Apple, 2019; Taylor,

1997) and incorporate perspectives in applied linguistics that center the communicative practices

of multilinguals (particularly those from minoritized backgrounds) as part of a social justice

agenda to overturn colonialist norms of race, nationhood, and language (e.g., García & Li, 2014;

May, 2013). Specifically, we ask, how do California’s Proposition 58, EL Roadmap, California

2030, and 2016 Teacher Performance Expectations (TPE) provide affordances for or constraints

upon translingual approaches in schools? Given that translanguaging perspectives eschew top-

down approaches to language planning and curricularization, we acknowledge the tensions in

this inquiry. Thus, as our methods section further details, we focus on affordances for

translanguaging approaches such as references to elevation of students’ familiar linguistic and

cultural assets and connections to language as it is used in students’ communities which we

conceptualize as preconditions and implicit tenets of a translanguaging lens rather than explicit

promotion of translanguaging.

4

Our goal is to elucidate opportunities for educational equity amid the revival of bilingual

education, while noting risks based on current and historical patterns in the education of

multilingual learners. Moreover, we approach this work from the position of teacher educators

preparing future bilingual teachers who themselves were denied access to bilingual education,

and who will be on the front lines of policy interpretation and implementation in their classrooms

(Menken & García, 2010). We are therefore particularly mindful of the persistent disconnect

between student-aimed policies and teacher preparation and have elected to analyze specific

language-in-education policies (Prop 58, EL Roadmap), an overarching policy framework

(California 2030), and corresponding teacher preparation standards (California TPE) to examine

their individual translanguaging affordances as well as their tensions or complementarity.

This work unfolds in four parts. First, our theoretical framework and literature review

interweave translanguaging perspectives with Language Policy and Planning (LPP) to note how

educational language policy shapes schooling experiences for linguistically minoritized groups.

Next, we situate our inquiry within Critical Policy Analysis to explain how our focal policies

correspond to historical and contemporary conditions regarding affordances for translanguaging

and equity for multilingual learners. Then, we examine four relevant policies: 1) California’s

Prop 58, which overturned Prop 227’s ban on bilingual education, 2) the English Learner

Roadmap (CDE, 2017), which articulates systemic and instructional commitments to support

multilingual learners, 3) the Global California 2030 initiative (CDE, 2018) that provides an

overarching vision and framework for multilingual education in the state, and 4) Teacher

Performance Expectations ([TPEs] CTC, 2016) that guide teacher preparation. Lastly, we discuss

how these legislative victories for bilingual learners and bilingual education, taken together, can

foster translingual practices in classrooms and what risks educators must avoid to do so. We

5

begin, however, with a succinct overview of bilingual education policy in California during the

last quarter century to help contextualize our analysis.

California’s Bilingual Education Policy Context

Even prior to its incorporation into the United States in 1850, the territory now known as

California has been a linguistically and culturally diverse expanse. As with other states in the

union, support for languages other than English has undulated over time. For brevity, we focus

here on the most recent restrictions on bilingual education in the state and their reversal, and

refer interested readers to more comprehensive examinations of the broader history of bilingual

education and bilingual education policy in the United States elsewhere (Del Valle, 2003;

García, 2009; Kibbee, 2016; Wiley, 2014).

The 1990’s in California witnessed rising nativist sentiment, and bilingual education

became entwined with anti-immigrant rhetoric and campaigns. Proposition 227 was passed by

voters in 1998, merely four years after the state’s voters favored a ballot initiative excluding

undocumented immigrants from public benefits including education (that initiative, Prop 187 of

1994, was struck down as unconstitutional and never took effect). Dubbed “English Language

Education for Immigrant Children,” the law proposed under Prop 227 ignored that many EL-

classified students were in fact US-born and that over two-thirds of them were in English-only

programs already (Matas & Rodríguez, 2014), nevertheless charging that California schools

were, “wasting financial resources on costly experimental language programs whose failure over

the past two decades is demonstrated by the current high drop-out rates and low English literacy

levels of many immigrant children,” (CA Secretary of State, nd). The law severely curtailed

bilingual education by requiring that all EL-classified students be placed in sheltered English

immersion programs for a transitional one year period before entering mainstream English-only

6

instruction. Bilingual education was prohibited unless a critical mass of parents at any given

school submitted annual signed waivers. Scholarship examining the effects of Prop 227

identified a substantial decrease in the proportion of the state’s EL-classified students receiving

bilingual instruction as mostly only the schools with strong, entrenched bilingual programs

adopting the waiver process (Gándara, et al., 2000; García & Curry-Rodríguez, 2000), no gains

in student achievement (Matas & Rodríguez, 2014), and lesser preparation of teachers to serve

bilingual learners in the state (Ulanoff, 2014).

This state-level restriction was aggravated by federal mandates for standardized testing

under the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2001. New school accountability measures

relied on high-stakes standardized tests to assess student progress generally as well as the

specific growth of EL-classified students towards attaining English proficiency. Given that this

standardized testing was in English, the law resulted in further reductions in bilingual

programming (Crawford, 2007; Menken, 2009; Menken & Solorza, 2014), with scholarship

noting constriction on the curricular experiences of bilingual students (Darling-Hammond, 2007;

Menken, 2009). Although reauthorization of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2015 as the Every

Student Succeeds Act addressed some of the most egregious issues with NCLB such as requiring

uniform policies within states for identifying English Learners and reclassifying them as English

proficient, it left in place the mechanism of high stakes testing.

As the above cited works attest, mounting evidence pointed to the drawbacks of these

policies on students’ educational experiences and attainment. Coupled with a growing interest

nationwide in bilingualism and bilingual education even among English-dominant, affluent

families (Delavan, et al., 2021; Flores, 2016), the stage was set for California to repeal its ban on

bilingual education. In 2016, voters approved Proposition 58, also known as the California

7

Education for a Global Economy Initiative (CA Ed.G.E), which overturned Prop 227. As we

discuss further in our analysis, early scholarship on Prop 58 has not identified effects in terms of

the number of bilingual programs or student outcomes, but has noted that the framing of

bilingual education has evolved from one of civil rights and cultural responsiveness to a more

generalist and utilitarian focus on the economic, national security, and diplomacy benefits of

multilingualism (Katznelson & Bernstein, 2017; Kelly, 2018).

Theoretical Framework

Our twofold theoretical framework encompasses how California’s policy changes enable

(or suppress) translingual pedagogies. We draw from LPP scholarship, which explores how state

action shapes which linguistic practices are used and valued in a society. We also draw from the

burgeoning literature on translanguaging to identify specific theoretical and practical dimensions

that bear on the possible outcomes of policy implementation in California.

Translanguaging and Translingual Pedagogies

Translanguaging as a theory of language offers that a bi/multilingual language user’s

communicative features and practices correspond to a singular repertoire from which they draw

strategically for meaning-making rather than distinct linguistic systems (García, 2009; 2017). In

other words, translanguaging normalizes the practices of bi/multilinguals, such as mixing

features from across political languages (“Spanish,” “English,” “French,” etc.) and across

registers, rather than the monolingual paradigms and adherence to standardized forms of

language that predominate in educational language policy. Applied linguists advancing

translanguaging frameworks thus argue that current frameworks imposing expectations for

“native-like” performance of standardized form of language through mechanisms such as testing

8

and scripted curriculum, including requirements for strict language separation in bilingual

programs, reify social hierarchies rooted in colonialism and nation-state governmentality (Flores,

2013). Instead, advocates of translanguaging approaches propose educational language policies

that place the rights and dignity of language users at the forefront and language itself as a

subsequent consideration (Poza, 2021). They seek policies that make space for community-

engaged pedagogy that affirms students’ and their families’ communicative practices and

expressly challenges the power relations embedded in linguistic interaction (García, 2017; Poza,

García, & Jiménez-Castellanos, 2021).

The translingual project is conceived in this paper as a triadic framework:

translanguaging as a humanizing activity (i.e., centered on speakers/students, see García-Mateus

& Palmer, 2017; Li, 2018), translanguaging as fluidity (i.e., integrative meaning-making

practices, see Hua, Li, & Lyons, 2017; Pennycook, 2017), and translanguaging as liberatory (i.e.,

counter-hegemonic, anti-oppressive work, see García & Leiva, 2014; Prada & Nikula, 2018).

The underlying assumption is that these constitutive tenets are mutually dependent,

complementary, in the conception and enactment of a translingual/heteroglossic policy.

Therefore, distance from these principles in the policy streams analyzed can be construed as

indicative of the degree of receptiveness of the translingual project.

Language Policy and Planning (LPP)

LPP considers the ideological and functional aspects by which specific languaging

features and practices (and, concurrently, the people who use them) are elevated or oppressed

within a society (Tollefson, 1991). Beyond legislation, governments also rely on policy

mechanisms such as standardized testing to engineer particular linguistic outcomes (Shohamy,

2006). Although language planning is by definition never neutral, it is not inherently negative

9

and can, in fact, serve to revitalize and affirm minority languages within a society (Hornberger,

1998). In the US, however, scholars have noted both the direct policy efforts to suppress

languages other than English (Crawford, 2000; del Valle, 2003; Faltis, 1997; Gándara et al.

2010; Wiley, 2014; Wiley & García, 2016; Wiley & Lukes, 1996) as well as how standardized

testing in English undermines bilingual education (Menken, 2009; Menken & Solorza, 2014;

Poza & Shannon, 2020).

Nonetheless, scholars of LPP observe that top-down language policy efforts do not

always achieve their stated goals. Layers of interpretation and implementation leave room for

deviation or outright defiance given the interstitial spaces between legislative and regulatory

enactment and practical execution (Ricento & Hornberger, 1996). Classrooms especially create

spaces for agency and local language policy negotiation as students, teachers, and families

engage their diverse communicative practices, sometimes even creating the social conditions for

bottom-up policy influence (García & Wiley, 2016; Hornberger & Johnson, 2007; García &

Menken, 2010; Ricento & Hornberger, 1996). While this work centers analysis of the top-down

policy efforts in California to foment multilingualism, we consider in our conclusion how

translingual practices may indeed correspond more aptly to this local and bottom-up dimension.

Translanguaging and Educational Policy

As described above, translanguaging scholarship builds on sociolinguistic and

anthropological research positioning language as a social practice governed by local norms of

interaction. Translanguaging critiques structural approaches to language as remnants of

colonialism that reinforce the marginalization of linguistically and racially minoritized groups

(García, 2009; García & Li, 2014; Mignolo, 1996) and specifically counters the kinds of social

control efforts constituted by many language planning regimes that promote monolingualism or

10

adherence to standardized forms of language. In this manner, translanguaging positions itself as

“part of a moral and political act that links the production of alternative meanings to

transformative social action” (García & Li, 2014, p. 37).

Applied to LPP, translanguaging perspectives reject monolingual impulses of US policy,

calling instead for school organization and curriculum that affirms and sustains community

linguistic practices within multilingual ecologies (Hornberger, 2003; Kramsch & Whiteside,

2008). Prior work applying translingual lenses to educational policy has considered the Common

Core State Standards (CCSS) (Flores & Schissel, 2014; Rymes, et al., 2016) as well as relevant

guidance documents (Poza, 2016) to critique monolingual orientations and highlight

opportunities for translingual practice within them. Unlike the CCSS, however, California’s

recent policy changes are specifically aimed at supporting multilingual development, and the

expectation might be that translanguaging would enjoy more official support. This is precisely

the issue we examine.

Methods

Critical Policy Analysis

Critical Policy Analysis (CPA) empirically investigates how global political and

economic forces interact with domestic policy to shape educational practice (Rata, 2014; Taylor,

1997). Notably, the method elucidates tensions between global capitalist patterns of exploitation,

austerity, and privatization alongside aspirations for education as an engine of social mobility

and positive social change (Apple, 2019; Rata, 2014). Pioneers in CPA (e.g., Apple, 1982; Ball,

1991) criticized assumptions that policy and policy research were objective, rational processes

conducted with complete information. Instead, they highlighted the role of power and ideology

11

in policymaking and called attention to the disparate impacts of certain policies on minoritized

groups (Diem, Young, & Sampson, 2019).

Examining our selected California policies through a CPA lens required iterative coding

and analysis. Based on major distinctions raised in prior research between allowing or restricting

bilingual education and our research questions, we began with structural codes (Saldaña, 2009)

capturing specific text segments within the policy documents that encouraged or constrained

bilingual approaches, particularly translanguaging, as well as conspicuous “silences'' that reified

an unjust status quo (Foucault, 1990). We followed with elaborative coding (Saldaña, 2009) for

construct refinement by applying themes identified in existing research that examines policy

through a translingual focus (e.g., Poza, 2016) and possible interpretations in light of concurrent

and historical discourses in official guidance documents, policy white papers, practitioner

conference programs, and district action plans (the “policy stream”). This latter stage

foregrounded the importance of intertextuality, referring to the need to analyze individual

discursive acts (such as policy documents) not in isolation but with consideration of their

histories and the broader discursive environments in which the texts were produced and are

consumed (Fairclough, 1989). Developed by Kristeva (1986) and rooted in Bakhtin´s dialogism,

intertextuality as an analytical concept elucidates how texts partake in co-constructed discourse

lineages by in the process of cross-referencing themselves and each other (Johnstone, 2017;

Tannen et al., 2015). Thus, our elaborative codes focused on whether references to bilingualism

were monoglossic (rooted in notions of standardized language and separate linguistic repertoires

for bilinguals) or heteroglossic (attuned to translingual perspectives of language and language

development) (García, 2009), and whether bilingualism and bilingual education were positioned

12

merely as human capital enhancement or pursuant to an anti-racist civil rights agenda (Flores,

2016). Our codes are summarized in Table 1 below.

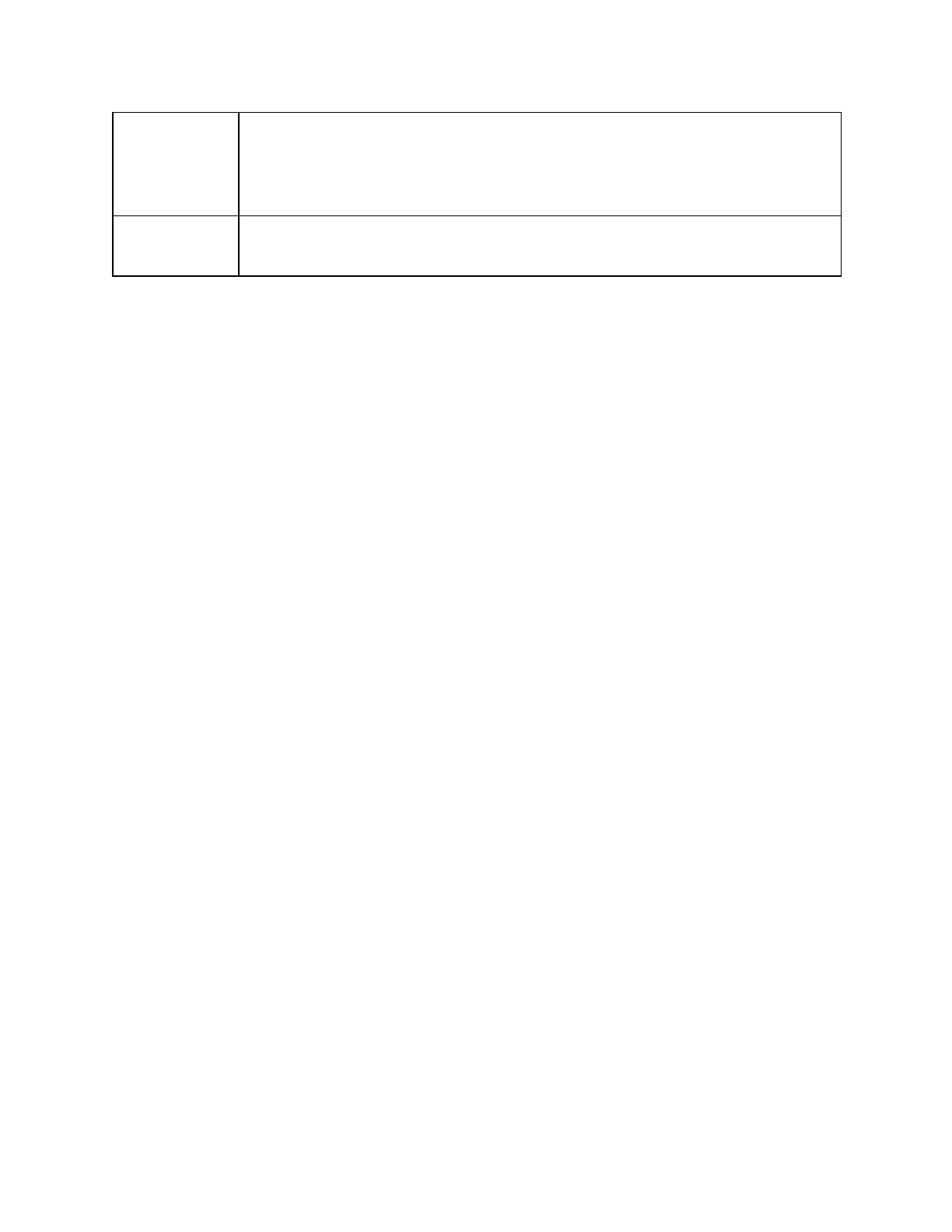

Table 1 - Codes and Examples

Structured Codes

Code

Example

Encouraging

bilingual

approaches

“Bilingualism provides benefits from the capacity to communicate in more

than one language and may enhance cognitive skills, as well as improve

academic outcomes.” (EL Roadmap, p. 3)

Allowing

bilingual

approaches

“All parents will have a choice and voice to demand the best education

programs for their children, including access to language programs” (SB

1174, p. 5)

Constraining

bilingual

approaches

“...literacy in the English language is among the most important of these

[skills]” (SB 1174, p. 5)

Conspicuous

silence

“California’s K-12 education system has made great strides in teaching world

languages to students, providing more opportunities for fluency and the

benefits fluency brings.” (Global California, p. 4) - Silent regarding status

distinction between learning a “world language” (though Spanish pre-dates

English in CA) and learning English; silent regarding criteria for fluency that

may devalue community language practices deemed non-standard.

Elaborated Codes

Code

Example

Heteroglossic

affordances

“Many English learners represent the newest members of our society

(including recently arrived immigrants and children of immigrants) who bring

a rich diversity of cultural backgrounds and come from families with rich

social and linguistic experiences. They also bring skills in their primary

languages that contribute enormously to the state’s economic and social

strengths as a talented multilingual and multicultural population.” (EL

Roadmap, p. 1)

Monoglossic

orientations

“California has the unique opportunity to provide all parents with the choice

to have their children educated to high standards in English and one or more

additional languages…”(SB 1174, p. 4)

13

Civil rights

orientation to

bilingualism

“Providing more equitable funding and local control, allowing communities to

determine how to best meet the educational needs of the students they serve.”

(Global California 2030, p. 5)

Human capital

orientation

“California employers across all sectors, public and private, are actively

recruiting multilingual employees…” (SB 1174, p. 4)

Policy Selection and Review

We selected our four focal policies on the basis of their direct relation to pedagogical

practice and its ideological context. Taken as an analytic whole, the stream of these policies and

their tributaries of guidance, regulation, and scholarship chart a specific vision for educating

linguistically minoritized youth. By overturning Prop 227, Prop 58 marked a crucial turning

point in the state’s educational vision. The EL Roadmap, by its specific mention of asset-

orientations to the linguistic resources that students classified as EL bring to their learning and its

ambitious scope of cohesive, meaningful learning experiences, adds potential for translingual

perspectives that affirm community multilingualism. Similarly, California 2030, a

comprehensive vision for increasing multilingual instruction in the state, invokes asset-

orientations regarding emergent bilinguals. Lastly, the revised TPE’s could connect the lofty

goals of the first three policies to specific knowledge and skills that teacher candidates must be

able to implement. That is, policies that favor bilingual approaches are meaningless if teachers

are not expected to learn linguistically responsive and culturally sustaining pedagogies (CSP) to

enact them.

Our analysis excludes California’s Seal of Biliteracy, recognition of the state’s high

school graduates deemed proficient in English and one other language, even though this too is an

important element in reviving bilingual education in the state. We exclude it in consideration of

space limitations, recognition that excellent scholarship has already examined the policy’s

14

benefits vis-a-vis raising the status of bilingual education and drawbacks in terms of

undermining the civil rights concerns of racialized bilinguals in favor of human capital

development arguments that perpetuate hierarchies among language varieties and the

racialization of certain bilingual communities (Subtirelu et al., 2019; Valdés, 2020).

Translanguaging in Selected California Policies

Proposition 58

Proposition 58, introduced as EdGE (Education for the Global Economy) and renamed

LEARN (Language education, Acquisition, and Readiness Now), overturned the English-only

mandates of Proposition 227. With a 73.5% passage support, it facilitated bilingual education by

lifting stringent requirements with regards to parent requests. Proposition 58 incarnated Senate

Bill 1174 (Lara, 2014) and seemed to crystallize a policy trend heralded by the groundbreaking

2011 Seal of Biliteracy (Brownley, 2011). While celebrated, however, the b-word was not

coming back por la puerta grande (not through ”the main gates”) but notably silenced in the

proposition and replaced by “multilingualism”, as the apparently resounding passage of the

proposition masked conflicting attitudes towards cultural diversity among the California

electorate. Katznelson and Bernstein (2017) highlight that 1 million Trump voters also supported

proposition 58, complicating any inference of mandate emerging from the ballot box.

The superficial reading of alleged changes in linguistic sensitivities in California

combined with causal arguments based on demographic shifts are also to be dimmed in light of

the critical analysis of the text itself. Based on survey studies preceding the November 2016

election, Citrin, Levy, and Wong (2017) argue that the title and framing of the initiative (starting

with the words “English proficiency¨”) may have triggered approval among conservative voters

15

who otherwise, when informed about the repeal of proposition 227, would have voted against it.

Aware of the prospects of certain opposition and armed with the handbook of the political realist,

it seems plausible that the developers of the proposition embraced a pragmatist approach

capitalizing on language-as-a-resource policy orientation (Ruiz, 1984).

With an emphasis on commodified language in a globalized era, the extant literature has

consistently highlighted the neoliberal ideological substratum in the policy. In their analysis of

neoliberal governmentality, Martín Rojo and Del Percio (2019) focus on the linguistic

implications derived from the current regimes of power and control that characterize late-

capitalism, and how they influence the ontology and epistemology of speakers and language.

Petrovic, for instance, notes that “The resource orientation appeals to neoliberal economic forces

to promote cultural pluralism and prop up language diversity... to undermine the civil rights

gains of the 1960s and 1970s" (2005, p. 400) in reference to the alignment of bilingual education

advocacy with commodifying capitalist discourses that may allow languages other than English

but do not inherently resist privatization and defunding of public programs like education.

Similarly, Flores (2019) states, “at the core of the neoliberal governmentality are heteroglossic

language ideologies that develop conceptualizations of language that take bi/multilingualism as

the norm” (p. 57). Thus, our concern in critically analyzing the policy focused on identifying

such “heteroglossic seeds,” ascertaining the degree to which Prop 58 may be fertile for

translingual approaches or, rather, patake in the neoloiberal governmentality logic that

alternatives are not possible. Beyond the resounding silences around equity for linguistically

minoritized populations and the recognition of the long road of bilingual and civil rights

struggles in the state, the linguistic notions and the linguistic imagery embedded in proposition

16

58 are anchored in distinct but interrelated pillars of monoglossic ideology, namely English

centrality, native-speaker ideology, and language objectification.

The bill emphasizes nation-state discourses and reasserts English primacy. The preamble

defines an ideological package inherited from proposition 227 reinforcing monoglossic English-

as-the-norm, “Whereas the English language is the national public language of the United States

of America and the state of California” (Section 2[a]), with old meritocratic ideological lore,

“Whereas all parents are eager to have their children master the English language and obtain a

high-quality education, thereby preparing them to fully participate in the American dream of

economic and social advancement" (Section 2 [b]). Echoing Duchêne and Heller's "pride" and

"profit" (2012), it is worth noting how the nationalistic strain of the policy is undergirded by the

electoral siren's song of California’s linguistic and economic exceptionalism.

By partitioning the body of students binarily as either “English learners” or “native

speakers of English” (305. (a)(1), and 306 (a) and (b)p. 95), Prop 58 reinforces the schema of the

mythical native speaker (Bonfiglio, 2013), proficient by virtue of being born into the named

language. Moreover, monoglossic ideological strands coordinate by reserving “nativeness” for

English speakers, further reinforcing English centrality. In a noteworthy metalinguistic turn in

the legislative text, “native speakers” are defined in the bill as those who “learned and used

English in their homes from early childhood with English as their primary means of concept

formation and communication” (pp. 6-7). From this metalanguage, the connection between the

construct of a named language and the assumed determinism over early cognitive processes

stands out. Such a conceptual turn in a legislative text may strike the reader as rhetorical and

reinforces the ideological current of biologization that undergirds the native-speaker concept

(Bonfiglio, 2013).

17

The text's emphasis on economic advancement and California's global role depends on

the exploitation of commodified linguistic resources (Heller, 2010) and instrumental

multilingualism (Bernstein, et al., 2015). The proposition's metaphorical language reveals an

inconspicuous objectification of language intermingled with its stated purposes: "California has a

natural reserve of the world's largest languages, including English, Mandarin, and Spanish,

which are critical to the state’s economic trade and diplomatic efforts.” (2.f., p.94). As it will be

later discussed, such reification contributes to monoglossic language ontologies by increasing the

discreteness of named languages and the perceived boundaries among them.

Certainly, the decisive breakthrough in proposition 58 is the overturn of the suffocating

pre-existing framework. The question has already been raised by researchers and theorists (see

Flubacher & Del Percio, 2017; Rojo & Del Percio, 2019) that have decried the neoliberal

emphasis on linguistic resource extraction: At what cost and for whom? Can the downplay of

critical racial and linguistic concerns serve a higher policy purpose? This cannot fully be

adjudicated on the basis of proposition 58 alone, but in scrutinizing the discursive stream that

emanated from prop 58. In other words, historical distance will tell if the policy has served as a

muted contestation of proposition 227, or a strategic long-range move to lift the restrictions on

the growth of a bilingual critical mass. Thus, the next sections attempt to delineate critically the

policy trajectory specifically with regards to the translingual project that concerns us.

EL Roadmap

The stated goal of California’s English Learner Roadmap (the “Roadmap”) is to provide

direction to Local Education Agencies (LEAs) in “welcoming, understanding, and educating the

diverse population of students who are English learners” (EL Roadmap, 2017, p. 1). It consists of

four principles: (1) Assets-oriented and needs-responsive schools; (2) intellectual quality of

18

instruction and meaningful access; (3) system conditions that support effectiveness; and (4)

alignment and articulation within and across systems. Within each principle, various "elements"

further clarify the intent.

Like Proposition 58, the EL Roadmap holds a strongly neoliberal perspective, albeit

softened by language of inclusion. For example, the policy’s introduction addresses ELs’

contribution “to the state’s economic and social strengths.” The mission statement claims,

“California schools prepare graduates with the linguistic, academic, and social skills and

competencies they require for college, career, and civic participation in a global, diverse, and

multilingual world, thus ensuring a thriving future for California.” The purpose of education,

according to the Roadmap, is for the economic success of the state and students’ college and

career readiness. In fact, the policy’s eight uses of variants of the term “college and career

readiness” suggest the purpose of educating ELs is statewide financial gains rather than the

benefits ELs might receive from education. While education can provide the potential benefit of

upward mobility for linguistically minoritized students (Callahan & Gándara, 2014), EL

students’ right to an appropriate education (Ella T. v. State of California settlement, 2020; Lau v.

Nichols, 1974) is understated in the policy.

The EL Roadmap’s mission statement explains that schools should “affirm, welcome and

respond to a diverse range of EL strengths, needs and identities.” While the terms “diverse” and

“diversity” together are used 12 times in the policy, when “diverse” is defined in the policy, it is

only as EL classification constructs (e.g., "newcomers, long-term English learners, students with

interrupted formal education," among others). However, the Roadmap’s acknowledgement of the

significant diversity within the EL population and the resulting variety of educational practices

19

that might therefore be required is a strength compared to prior policies that take a monolithic

view of ELs. Principle 1 Element B states:

Recognizing that there is no universal EL profile and no one-size-fits-all approach that

works for all English learners, programs, curriculum, and instruction must be responsive

to different EL student characteristics and experiences. EL students entering school at the

beginning levels of English proficiency have different needs and capacities than do

students entering at intermediate or advanced levels. Similarly, students entering in

kindergarten have different needs than students entering in later grades. The needs of

long term English learners are vastly different from recently arrived students (who in turn

vary in their prior formal education). Districts vary considerably in the distribution of

these EL profiles, so no single program or instructional approach works for all EL

students.

This statement leaves instruction open to a variety of approaches, including Translanguaging, for

educators who are seeking to implement it. In contrast, the Roadmap positions language as a set

of skills ("they also bring skills in their primary language”); its perspective on language learning

is that of building linguistic skills to participate in the global economy. Those skills are intended

to prepare students for “college and career readiness,” or to operate in settings that are

traditionally white and where standardized English is privileged. The skills-based approach to

language contrasts with practices that view language as practice (Palmer & Martinez, 2013),

such as translanguaging.

However, savvy educational leaders could interpret the Roadmap to defend

translanguaging pedagogies (Briceño & Bergey, 2022). The Roadmap does not address specific

theoretical perspectives or pedagogical practices. Instead, it requires “differentiated and

20

responsive” approaches to ELs’ diverse linguistic strengths and needs, thus opening the door

(albeit the back door) for translanguaging. The most significant opportunity for translanguaging

appears in Principle Two, which states that schools should "provide access for comprehension

and participation through native language instruction and scaffolding." This statement allows a

wide array of instructional practices that foster comprehension and communication-based

language development. However, as in Prop 58, the term “native language” evidences a

theoretical misalignment with translanguaging’s single linguistic reservoir (García & Li, 2014)

and underlying heteroglossic foundation.

While translanguaging views language as a social practice governed by local norms of

interaction, the EL Roadmap privileges “academic” English proficiency, with the term

“academic” used 18 times in the policy. Five of the references describe language (e.g.,

“academic language”), and the others describe a set of skills distinct from language (e.g.,

“linguistic, academic and social skills” in the mission statement). There is debate about the

definition of academic language (Valdés, 2004), and the operationalization of “academic

language” usually results in bi/multilingual students being assessed on an arbitrary, undefined

standard (Valdés et al., 2011). In this way, schools’ linguistic colonialism ignores the

communication practices of bi/multilingual communities (García & Li, 2014), results in students

being labeled as “semilingual” instead of multilingual (Edelsky, et al., 1983), and interferes with

students' ability to achieve the arbitrary "academic" standards required within a racist educational

system (Flores & Rosa, 2015).

While multilingualism is supported in the policy, the vision statement explains that EL

students should have “high levels of English proficiency” as compared with more vague

“opportunities to develop proficiency in multiple languages,” implying a hierarchy of

21

importance. Despite these constraints on translingual practices, the Roadmap’s acknowledgment

of ELs' linguistic diversity, the (limited) space for translingual practices, and the explicit

references to ELs’ assets are progress in the policy stream toward foundational ecological

conditions where heteroglossia and translanguaging could be implemented by agentive

educators.

California 2030

While undisputedly modest in its reach and mostly testimonial in nature, focusing on the

“California 2030: Speak, Learn, Lead” nonbinding initiative (CDE, 2018) allows for meaningful

qualifications in our analysis of the discursive trajectory in the Prop-58 policy stream. The text

serves as a corollary in bundling together the policy drive behind prop 58 and the ELL Roadmap.

Forward-looking in nature, the document lays out expectations for the growth of multilingualism

in the state and implications for teacher preparation, namely the shortage of authorized bilingual

teachers and the low number of bilingual teacher preparation programs.

Most importantly, California 2030 adopts an eclectic pluralism and carefully balances the

language as a right and language as a resource orientations (Ruiz, 1984). The document opens,

“the mission of global California 2030 is to equip students with world language skills to better

appreciate and more fully engage with the rich and diverse mixture of cultures, heritages, and

languages found in California and the world, while also preparing them to succeed in the global

economy” (p.4). As is the case throughout the document, economic arguments are systemically

counterbalanced with humanizing arguments foregrounding the speakers and the values of their

culture. The fact that both “economy” and “culture” (including their lexical derivatives) appear

six times, often in textual proximity of one another, further reinforces this assessment.

California’s Teaching Performance Expectations (TPEs)

22

The California TPEs (2016) outline the knowledge, skills, and abilities that teacher

candidates ought to possess upon licensure, and thus determine the content and structure of

teacher preparation programs. First developed by the commission on teacher credentialing in

2001, this policy was then revised in 2003 and fully redrafted in 2016 to establish structural

parallels with other documents in its policy ecology such as the California Standards for the

Teaching Profession (CTC, 2009a) or the Continuum of Teacher Practice (CDE, CTC, & NTC,

2012). Underlying teacher preparation, this policy logically occupies a pivotal position in

determining the relationship between aspiring teachers and language, the invocation of linguistic

targets, and the potential role that newly minted teachers may occupy as language policy agents.

The analysis underlying this paper has accordingly considered how the TPE conceptual

framework may cohere with the post-Prop 58 policy stream, and whether it may foster or

constrain teachers' engagement with translanguaging.

While the 2016 TPEs were approved in June 2016 and predate proposition 58, the

process of drafting and design overlapped with the ramping up of the proposition´s campaign.

However, while both partake in a policy discourse environment that heightens the role of

language in learning, lack of any intertextual connections or references to bilingual education is

most notable. Aside from structural modifications, this iteration of the TPEs departs from

previous editions in the recurring referencing of language throughout the document, which

brings the standards in an intertextual relationship with the English Language Development

standards (CDE, 2012) and, by extension, the English Language Arts/English Language

Development Framework (CDE, 2014). Throughout the description of expectations and specific

credentials, the TPEs identify “academic language” and “standard language” as linguistic targets

and English-language learners and Standard English Learners as specific populations in need of

23

linguistic support (Author 1, 2018). References to standard language and its “users” go from one

occurrence in the 2013 edition to 11 in the 2016 policy, whereas references to academic language

and ELLs go from 4 and 10 to 27 and 36, respectively. This marked linguistic turn in the TPEs is

associated with a monoglossic inclination in the identification of target linguistic varieties and

purported speaker subgroups, which the policy does not define or substantiate.

The TPEs remain agnostic with regard to bilingual education, and the minimal references

to languages other than English do so in the context of using the primary language as a scaffold

for English proficiency. Such silencing promotes the English-dominant status quo. It can be

argued that the de facto divorce between generalist and bilingual education after proposition 227

left its mark in the chasm between the TPEs in their recent iteration and the Bilingual

Authorization (BILA) Standards (CTC, 2009b), which regulate the credentialing of aspiring

bilingual teachers. Existing as a separate document and lacking overt intertextual ties with TPEs,

the BILA standards that apply to a limited subset of California teachers have become the de facto

repository of concrete bilingual-oriented knowledge, skills, and abilities, even though most

bilingual learners will not have access to bilingual instruction.

Discussion

In addressing how amenable the “return” of California bilingual education may be to the

translingual project in the preparation of new teachers, the sections that preceded have first laid

out the components of this policy ecology and presented a disconnect between the Prop 58 policy

stream and the basic reference in teacher preparation policy, the TPEs. This divide is exemplified

in practice by current funded policy initiatives that aim at the dissemination of the ELL Roadmap

as inservice opportunities (e.g., Educator Workforce Investment Grant, 2020), leaving preservice

24

programs to their own devices to incorporate these paradigmatic changes. However, the

discussion to follow will conceive such a vacuum as both a challenge and an opportunistic space

for the implementation of bottom-up, grounded, and transformative language policies.

Proposition 58’s foundation in nation-state discourse and nativism and its focus on

communication as a capitalist transaction present obvious barriers to hybridizing conceptions of

language. Partially modifying the steer of Prop 58, the ELL Roadmap and California 2030 bring

English Language Learners to the discourse focus. This “recentering” process is most noticeable

in the rhetorical progression of the 2030 policy, which espouses the language as a right argument

with a now proportionately attenuated Prop 58 economic impetus. However, the still palpable

neoliberal traits and solid monoglossic tenets in the Roadmap and 2030 frameworks raise doubts

as to the potential for top-down embrace of translanguaging, particularly with regards to its

unbounded fluidity leading to heteroglossic liberation.

In the case of California's Prop 58 policy stream, advocates and scholars face a decades-

old conundrum that pits pragmatism and policy realism (McGroarty, 2006) against fidelity to a

democratic and social agenda in education (Petrovic, 2005). Recently, García and Sung (2018)

reflected on the rise and demise of the Bilingual Education Act of 1968 (PL90-247), in which the

justice principles of activists were first withheld and finally diluted in the process, thus thwarting

the transformative potential of bilingual education and laying the foundation for the English-

centric backlash that ensued. Alarming parallels can be drawn between present dynamics of

ethical concessions, the path charted by the expansion of elite bilingualism, and the 40-year-old

tensions that García describes, which played to the detriment of linguistically minoritized

students.

25

With regard to the discourse stream centered around the TPEs, our analysis indicates that,

while language gains relevance as a learning factor, the conceptual foundations behind this

linguistic turn remain unequivocally monoglossic. In fact, the 2016 TPEs echo the linguistic

thrust behind other state policy documents, such as the 2014 ELA-ELD framework, that build on

the linguistic momentum propelled by the Common Core Standards. The TPEs, therefore,

gravitate around traditional language targets such as "standard" and "academic" English, which

are heavily inscribed across all sets of content standards and discursively reinforced by the

curricularizing influence of scholars, consultants, and advocates (Leung & Valdés, 2019).

While the present analysis has described a policy stream evolving towards the

humanizing orientation of language as a right, skepticism remains with regard to the policy

momentum to grow in the direction of the translingual project. For one, at the general level,

education is but an arena among many imbued by the logic of neoliberal governmentality

(Martín Rojo & Del Percio, 2019) which, while predicated on arguments of freedom, flexibility,

and adaptability in structures and the human capital, still profits from the reified/commodified

constructs of the nation-state ideologies. In other words, the neoliberal world order is still

predicated in hierarchical othering and monopolistic regimes that justify inequity and

minoritization. Second, concerning LPP, modernist top-down conceptions of policy underlying

the prop 58 policy stream and the TPE iterations are at odds and struggle with concepts and

practices that elude objectification and explicit regulation by a policy, such as the case of

translanguaging. To illustrate this dynamic, Flores and Schissel (2014) elaborate on the local

appropriation of the CCSS in the New York State Bilingual Common Core Initiative, the

resulting heteroglossic affordances seized in two classrooms and the tensions with the

monoglossic testing regime. Accordingly, hope for policies that embrace the translingual project

26

can be found in bottom-up ecological (Mühlhäusler, 2000) and ethnographic approaches

(Johnson, 2009) to LPP that put the spotlight on carving out such ideological and

implementational spaces and emphasize the policy agency of educators as grounded actors

(García and Menken, 2010). Exemplifying this in the CA context, Martínez and Mejía (2020)

conveniently interrogate the concept of “academic English” and exhort practitioners to be

mindful of their agency and potential by demonstrating how a student in central Los Angeles

employs his fluid linguistic repertoire to engage in communicative interactions that fulfill

linguistic expectations outlined in the CCSS.

As discussed earlier, the disconnect between the Prop 58 policy stream and the TPEs

presents a challenge from a modernist-rationalist policy perspective, since such a stance aspires

at controlling the LPP process and achieving calculated linguistic results. Conversely, from an

ecological and ethnographic perspective, this disconnect presents transformational educators

with an ideological space to be filled up. With the California Commission on Teacher

Credentialing (CTC) launching a committee of bilingual field practitioners and scholars to

review the BILA standards (and add a newly developed set of bilingual TPEs to complement in a

one-to-one correspondence the general TPEs) in May 2020 and its work through 2022

1

, a

window of opportunity is opening up before progressive bilingual teachers and California teacher

educators. Building on the momentum of the ELL Roadmap, a collaborative of teacher educators

and advocates published a white paper (Bilingual Standards Refresh Work Group, 2020)

evidencing the field’s desire to account for recent and important developments in bilingual

education such as translanguaging. While affecting the monoglossic status from the single angle

of bilingual teacher preparation may have limited leverage, it paves the way for a future

1

Author 1 serves on this committee. The BILA standards were approved in December 2021 but the full policy,

comprehending planning questions and implementation regulations, is expected to be approved in 2022.

27

replenishment of the system with educators that have explicitly learned and tackled the

monoglossic-heteroglossic tension. Given that this committee´s work is still subject to

commission approval and input from the field and that, if approved, it will take one to two years

to become a firm mandate, due caution needs to be exercised with its potential outcomes and its

role in influencing the trajectory of the Prop 58 policy stream.

Conclusion

This article has discussed the conditions for the development of translingual perspectives

and practices in light of recent developments in language policy and teacher preparation policy in

California. Proposition 58 and the ensuing stream of policies evolved towards a language-as-a-

resource-and-as-a-right integrative approach that ultimately ignored paradigmatic linguistic

differences. Concerning teacher preparation, the TPEs have evolved over the years to

discursively mirror and cohere with the monolingual perspective of language present in the

general education standards. Ultimately, while intertextually disconnected, both the Prop 58 and

the TPE policy streams remain discursively anchored in monoglossic conceptions of language,

limiting the potential for translanguaging.

Nevertheless, the acknowledgment of the silences and ambiguities within and between

our target policy streams allows us to conclude with a call to action for educators and teacher

educators as policymakers to occupy such ideological and implementational spaces (Flores &

Schissel, 2014). The growing translanguaging scholarship needs to be capitalized on to enrich

conversation between research and policymaking, which entails the legitimate recognition of

ecological LPP approaches within the general field of education policy. Capitalizing on the

unique features of the California bilingual dynamics, this study captures the ideological

28

morphing of policy discourses over time with critical policy analytical implications that can

transfer to other contexts (e.g., the deconstruction of neoliberal framings of bilingualism in other

states; global neoliberal discourses of language stardization and regimes of control, see Martín

Rojo & Del Percio, 2019) and its ramifications in teacher preparation language policy discourses

(i.e., possibilities for agentic reappropriation of language policy).

By shedding light on the historical progression of bilingual policy in California, this

article raises the possibility of future heteroglossic policy trajectories that merit additonal

research: A translingual and CSP-inspired revision of the bilingual authorization standards in

California could serve as an influence platform for the next iteration and reframing of the general

TPEs. Accordingly, we want to highlight the potential of seemingly peripheral policies to

contribute heteroglossic conditions that may influence the redrafting of exisiting monoglossic

policies in the ecology in California and beyond. At a micropolicy level, teacher preparation

programs may benefit from including critical policy awareness content in coursework (e.g.,

sociology of education courses in interaction with English Learner-related courses) and clinical

experiences (e.g., analysis of the interaction among state, district, and school language policies),

the exploration of educator agency and, importantly, practical advice on successful language

activism in diverse micropolitical professional contexts given teachers’ ability to serve as local

policy agents (Wiley & García, 2016; Hornberger & Johnson, 2007; Menken & García, 2010;

Ricento & Hornberger, 1996). Following from the work of Somerville and Faltis (2019), who

note bilingual students’ translanguaging as a subversive tactic in light of language separation

requirements within their dual language programs, we argue that educators can operate within

the strategies of new policy to open doors for bilingual instruction and adopt translingual

perspectives and student-centered linguistic curriculum as tactics for CSP. As a much-needed

29

result, new generations of translingual teachers may interrogate the ideological foundations

behind the current policy status quo (e.g., standardized testing regimes), how to carve

translingual spaces in them, and how to make these practices not only compatible with, but

necessary to, their existence and agency in the educational system. In advancing the cause of a

heteroglossic learning ecology, the critical scrutiny of teacher education and EL policies by

teacher educator activists is a necessary and actionable first step.

30

References

Alamillo, L., Palmer, D. K., Viramontes, C., & Garcia, E. (2005). California’s English-only

policies: An analysis of initial effects. In A. Valenzuela (Ed.), Leaving children behind:

How Texas-style accountability fails Latino youth (pp. 201–224). SUNY Press.

Apple, M. W. (1982). Education and Power. London: Routledge.

Apple, M. W. (2019). On doing critical policy analysis. Educational Policy, 33(1), 276-287.

Ball, S. J. (1991). Politics and policy making in education. London, England: Routledge.

Bernstein, K. A., Hellmich, E. A., Katznelson, N., Shin, J., & Vinall, K. (2015). Introduction to

Special Issue: Critical Perspectives on Neoliberalism in Second / Foreign Language

Education. L2 Journal, 7(3), 3–14

Bilingual Education Act (1968). Publ. No. (90–247), 81 Stat 816.

Bilingual Standards Refresh Work Group. (2020). Bilingual authorization program standards

content analysis white paper. Loyola Marymount University Center for Equity for English

Learners & The Sobrato Foundation. Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved from

https://soe.lmu.edu/media/lmuschoolofeducation/departments/ceel/contentassets/documents/

BilingualAuthorization_ContentStandards_WhitePaper-Final.pdf

Bonfiglio, T. P. (2013). Inventing the native speaker. Critical Multilingualism Studies, 1(2), 29-

58.

Briceño, A. & Bergey, R. (2022). Policy Implementation: Navigating the English Learner

Roadmap for Equity. Journal of Leadership, Equity, and Research, 8(1), 24-33.

Brownley. CA Assembly Bill 815 (2011).

31

California Department of Education. (2012). English language development standards. Common

Core State Standards California, California Department of Education, Sacramento, CA.

Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/el/er/documents/eldstndspublication14.pdf

California Department of Education. (2014). ELA/ELD framework. California Department

of Education: Sacramento, CA. Retrieved from

https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/rl/cf/elaeldfrmwrksbeadopted.asp

California Department of Education. (2017). English Learner Roadmap. California Department

of Education: Sacramento, CA. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/el/rm/index.asp

California Department of Education (2018). Global California 2030: Speak, learn, live.

California Department of Education, Sacramento, CA. Retrieved from

https://www.cde.ca.gov/eo/in/documents/globalca2030report.pdf

California Department of Education (2020). Educator workforce investment grant program.

California Department of Education, Sacramento, CA. Retrieved from

https://www.cde.ca.gov/pd/ps/ewig.asp

California Department of Education, Commission on Teacher Credentialing & New Teacher

Center (2012). Continuum of teaching practice. Sacramento, CA. Retrieved from

https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/ca-ti/final-continuum-of-teaching-

practice.pdf

California Secretary of State. (nd). English language in public schools. Initiative Statute.

https://vigarchive.sos.ca.gov/1998/primary/propositions/227text.htm

Callahan, R. M., & Gándara, P. C. (Eds.). (2014). The bilingual advantage: Language, literacy

and the US labor market. Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.

32

Citrin, J., Levy, M., & Wong, C. J. (2017). Politics and the English language in California:

Bilingual education at the polls. California Journal of Politics and Policy, 9(2). 1-14.

Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2009a). California standards for the teaching profession

(CSTP). Commission on Teacher Credentialing, Sacramento, CA. Retrieved from

https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/CSTP-2009

Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2009b). Bilingual Authorization Program Standards.

Commission on Teacher Credentialing, Sacramento, CA. Retrieved from

https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/standards/bilingual-authorization-

handbook-pdf.pdf

Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2016). California teaching performance expectations.

Commission on Teacher Credentialing, Sacramento, CA. Retrieved from

https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/standards/adopted-tpes-

2016.pdf?sfvrsn=0

Common Core State Standards. (2010/2020). English language arts standards. Common Core

State Standards Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/

Crawford, J. (2000). At war with diversity: US language policy in an age of anxiety.

Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Crawford, J. (2007). The decline of bilingual education: How to reverse a troubling trend?.

International Multilingual Research Journal, 1(1), 33-37.

Darling‐Hammond, L. (2007). Race, inequality and educational accountability: The irony of ‘No

Child Left Behind’. Race, Ethnicity, and Education, 10(3), 245-260.

del Valle, S. (2003). Language rights and the law in the United States: Finding our voices.

Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

33

Delavan, G. M., Freire, J. A., & Menken, K. (2021). Editorial introduction: a historical overview

of the expanding critique (s) of the gentrification of dual language bilingual education.

Language Policy, 20(3), 299-321.

Diem, S., Young, M. D., & Sampson, C. (2019). Where critical policy meets the politics of

education: An introduction. Educational Policy, 33(1), 3-15.

Duchêne, A., & Heller, M. (Eds.) (2012). Language in late capitalism: Pride and profit. New

York and London: Routledge.

Edelsky, C., Hudelson, S., Flores, B., Barkin, F., Altwerger, B., & Jilbert, K. (1983).

Semilingualism and language deficit. Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 1-22.

Ella T. v. State of California, Settlement Agreement. (2020). Los Angeles County Superior

Court. Retrieved from https://media2.mofo.com/documents/200220-literacy-ca-ella-t-

settlement-agreement.pdf

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. London and New York: Longman.

Faltis, C. (1997). Bilingual education in the United States. In J. Cummins & D. Corson (Eds.)

Bilingual Education. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, vol 5. Dordrecht: Springer.

Flores, N. (2013). Silencing the subaltern: Nation-state/colonial governmentality and bilingual

education in the United States. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 10(4), 263-287.

Flores, N. (2016). A tale of two visions: Hegemonic whiteness and bilingual

education. Educational Policy, 30(1), 13-38.

Flores, N. (2019). Producing national and neoliberal subjects: Bilingual education and

governmentality in the United States. In L. Martín Rojo & A. Del Percio (Eds.), Language

and Neoliberal Governmentality. (49-68). New York: Routledge.

34

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language

diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149-171.

Flores, N., & Schissel, J. L. (2014). Dynamic bilingualism as the norm: Envisioning a

heteroglossic approach to standards‐based reform. TESOL Quarterly, 48(3), 454-479.

Flubacher, M. & Del Percio, A. (2017). Language, education and neoliberalism: Critical

studies in sociolinguistics. Bristol: Multilingual Matters

Foucault, M. (1990). The history of sexuality: An introduction. New York: Vintage.

Gándara, P., Maxwell-Jolly, J., Garcia, E., Asato, J., Gutierrez, K., Stritikus, T., & Curry, J.

(2000). The initial impact of Proposition 227 on the instruction of English learners.

University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute. Education Policy Center,

University of California Davis. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED470809.pdf

Gándara P., Losen D., August D., Uriarte M., Gómez M. C., & Hopkins M. (2010). Forbidden

language: A brief history of US language policy. In P. Gándara & M. Hopkins (Eds.),

Forbidden language: English learners and restrictive language policies (pp. 20–33). New

York, NY: Teachers College Press.

García-Mateus, S., & Palmer, D. (2017). Translanguaging Pedagogies for Positive Identities in

Two-Way Dual Language Bilingual Education. Taylor & Francis, 16(4), 245–255.

García, E. E., & Curry-Rodríguez, J. E. (2000). The education of limited English proficient

students in California schools: An assessment of the influence of Proposition 227 in

selected districts and schools. Bilingual Research Journal, 24(1-2), 15-35.

García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Malden, MA:

Wiley-Blackwell

35

García, O. (2017). Translanguaging in schools: Subiendo y bajando, bajando y subiendo as

afterword. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(4), 256-263.

García, O., Johnson, S. I., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging

student bilingualism for learning. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon.

García, O., & Leiva, C. (2014). Theorizing and Enacting Translanguaging for Social Justice

Educational Linguistics, (pp. 199-216) Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

García, O., & Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. New

York: Palgrave Macmillan.

García, O., & Sung, K. K. (2018). Critically assessing the 1968 Bilingual Education Act at 50

years: Taming tongues and Latinx communities. Bilingual Research Journal, 41(4), 318-333.

Heller, M. (2010). The commodification of language. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39, 101-

114.

Hornberger, N. H. (1998). Language policy, language education, language rights: Indigenous,

immigrant, and international perspectives. Language in society, 27(4), 439-458.

Hornberger, N. H. (2003). Afterword: Ecology and ideology in multilingual classrooms.

International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 6(3-4), 296-302.

Hornberger, N. H., & Johnson, D. C. (2007). Slicing the onion ethnographically: Layers and

spaces in multilingual language education policy and practice. Tesol Quarterly, 41(3), 509-

532.

Hua, Z., Li, W., & Lyons, A. (2017). Polish shop(ping) as translanguaging space. Social

Semiotics 27(4), 411–433.

Johnson, D. C. (2009). Ethnography of language policy. Language Policy, 8(2), 139-159.

Johnstone, B. (2017). Discourse analysis. John Wiley & Sons

36

Katznelson, N., & Bernstein, K. A. (2017). Rebranding bilingualism: The shifting discourses of

language education policy in California's 2016 election. Linguistics and Education, 40, 11-

26.

Kelly, L. B. (2018). Interest convergence and hegemony in dual language: Bilingual education,

but for whom and why?. Language Policy, 17(1), 1-21.

Kramsch, C., & Whiteside, A. (2008). Language ecology in multilingual settings. Towards a

theory of symbolic competence. Applied Linguistics, 29(4), 645-671.

Kristeva, J. (1986). The kristeva reader. Columbia University Press.

Lara. Senate CA Bill 1174 (2014). https://elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov/ballot-measures/pdf/sb-1174-

chapter-753.pdf

Lau v. Nichols, 414 US 563 (1974).

Leung, C., & Valdés, G. (2019). Translanguaging and the transdisciplinary framework for

language teaching and learning in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal,

103(2), 348-370.

Li, W. (2018). Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Applied Linguistics,

39(1), 9–30.

Martín Rojo, L., & Del Percio, A. (Eds.). (2019). Language and neoliberal governmentality.

London: Routledge.

Martínez, R. A., & Mejía, A. F. (2020). Looking closely and listening carefully: A sociocultural

approach to understanding the complexity of Latina/o/x students’ everyday language. Theory

Into Practice, 59(1), 53-63.

37

Matas, A., & Rodríguez, J. L. (2014). The education of English Learners in California following

the passage of proposition 227: A case study of an urban school district. Penn GSE

Perspectives on Urban Education, 11(2), 44-56.

May, S. (Ed.). (2013). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual

education. New York and London: Routledge.

McGroarty, M. (2006). Neoliberal collusion or strategic simultaneity? On multiple

rationales for language-in-education policies. Language Policy, 5(1), 3-13.

Menken, K. (2009). No Child Left Behind and its effects on language policy. Annual Review of

Applied Linguistics, 29, 103-117.

Menken, K., & García, O. (Eds.). (2010). Negotiating language policies in schools: Educators as

policymakers. New York: Routledge.

Menken, K., & Solorza, C. (2014). No child left bilingual: Accountability and the elimination of

bilingual education programs in New York City schools. Educational Policy, 28(1), 96-125.

Mignolo, W. D. (1996). Linguistic maps, literary geographies, and cultural landscapes:

Languages, languaging, and (trans) nationalism. Modern Language Quarterly, 57(2), 181-

197.

Mühlhäusler, P. (2000). Language planning and language ecology. Current Issues in Language

Planning, 1(3), 306-367.

Muñoz-Muñoz, Eduardo R. (2018). Destandardizing the standard (s): ideological and

implementational spaces in preservice teacher education [Doctoral dissertation, Stanford

University] https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/12698948

Palmer, D. & Martinez, R. (2013). Teacher agency in bilingual spaces: A fresh look at

preparing teachers to educate Latina/o bilingual children. Review of Research in

Education, 13, 269-297.

38

Pennycook, A. (2017). Translanguaging and semiotic assemblages. International Journal of

Multilingualism, 14(3), 269–282.

Petrovic, J. E. (2005). The conservative restoration and neoliberal defenses of bilingual

education. Language Policy, 4(4), 395-416.

Poza, L.E. (2016). Barreras: Language ideologies, academic language, and the marginalization of

Latin@ English language learners. Whittier Law Review. 37(3). 401-421.

Poza, L. E. (2021). Adding Flesh to the Bones: Dignity Frames for English Learner Education.

Harvard Educational Review, 91(4), 482-510.

Poza, L. E., García, O., & Jiménez-Castellanos, Ó. (2021). After Castañeda: a glotopolítica

perspective and educational dignity paradigm to educate racialized bilinguals. Language

Policy, 1-24.

Poza, L.E. & Shannon, S.M. (2020). Where language is beside the point: English language

testing for Mexicano students in the Southwestern United States. In S.A. Mirhosseini & P.I.

De Costa (Eds). The sociopolitics of English language testing. (46-67). London, UK:

Bloomsbury.

Prada, J., & Nikula, T. (2018). Introduction to the special issue: On the transgressive nature of

translanguaging pedagogies EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages

Special Issue, 5(2), 1–7.

Rata, E. (2014). The three stages of critical policy methodology: An example from curriculum

analysis. Policy Futures in Education, 12(3), 347-358.

Ricento, T. K., & Hornberger, N. H. (1996). Unpeeling the onion: Language planning and policy

and the ELT professional. Tesol Quarterly, 30(3), 401-427.

Rubio, J. (2020). Educational Language Policy in Massachusetts: Discourses of the LOOK

39

Act. Educational Policy, DOI: 10.1177/0895904820974406

Ruiz, R. (1984). Orientations in language planning. NABE Journal, 8(2), 15-34.

Rymes, B., Flores, N., & Pomerantz, A. (2016). The Common Core State Standards and English

Learners: Finding the silver lining. Language, 92(4), e257-e273.

Saldaña, J. (2009). An Introduction to codes and coding: The coding manual for qualitative

researchers. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing

Shohamy, E. G. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches. New York and

London: Routledge.

Somerville, J., & Faltis, C. (2019). Dual languaging as strategy and translanguaging as tactic in

two-way dual language programs. Theory Into Practice, 58(2), 164-175.

Subtirelu, N. C., Borowczyk, M., Thorson Hernández, R., & Venezia, F. (2019). Recognizing

whose bilingualism? A critical policy analysis of the Seal of Biliteracy. The Modern

Language Journal, 103(2), 371-390.

Tannen, D., Hamilton, H. E., & Schiffrin, D. (2015). The handbook of discourse analysis. John

Wiley & Sons.

Taylor, S. (1997). Critical policy analysis: Exploring contexts, texts and consequences.

Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. 18:1, 23-35.

Tollefson, J. W. (1991). Planning language, planning inequality. New York: Longman

Ulanoff, S. H. (2014). California’s Implementation of Proposition 227. The mis-education of

English learners: A tale of three states and lessons to be learned, 79-107.

Valdés, G. (2004). Between support and marginalization: The development of academic

language in linguistic minority children. Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7(2&3), 102-

132.

40

Valdés, G. (2020). The future of the Seal of Biliteracy. In A.J. Heineke & K.J. Davin (Eds.) The

Seal of Biliteracy: Case studies and considerations for policy implementation. (177-204).

Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Valdés, G., Capitelli, S., & Álvarez, L. (2011). Latino children learning English: Steps in the

journey. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Wiley, T. G. (2014). Diversity, super-diversity, and monolingual language ideology in the United

States: Tolerance or intolerance?. Review of Research in Education, 38(1), 1-32.

Wiley, T. G., & García, O. (2016). Language policy and planning in language education:

Legacies, consequences, and possibilities. The Modern Language Journal, 100(S1), 48-63.

Wiley, T. G., & Lukes, M. (1996). English‐only and standard English ideologies in the US. Tesol

Quarterly, 30(3), 511-535.