i

EVALUATION OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF WESTERN

STATES’ AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES PUBLIC

AWARENESS CAMPAIGNS FOR ELICITING DESIRED

PREVENTION BEHAVIORS

FINAL REPORT

August 2022

Gerard Kyle, PhD

Department of Rangeland, Wildlife & Fisheries Management

Quinn Linford

Daniel Pilgreen

Trang Le

Department of Recreation, Park & Tourism Sciences

Richard Woodward

Department of Agricultural Economics

Contact:

Gerard Kyle

Department of Rangeland, Wildlife & Fisheries Management

Texas A&M University

2138 TAMU

College Station TX 77843-2261

Email: gkyle@tamu.edu

ii

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. iii

LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................ IV

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... V

1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................1

2.0 BACKGROUND ..............................................................................................................................2

3.0 STUDY DESIGN AND METHOD .......................................................................................................4

3.1 Key Informant Interviews .................................................................................................................... 4

3.2 Survey Questionnaire .......................................................................................................................... 4

3.3 Data Collection .................................................................................................................................... 9

3.4 Message Experiment - Manipulation Check ..................................................................................... 12

4.0 SAMPLE PROFILE ........................................................................................................................ 14

5.0 STUDY FINDINGS ........................................................................................................................ 19

5.1 Familiarity with Clean, Drain, Dry ..................................................................................................... 19

5.2 Awareness and Concern over Aquatic Invasive Species ................................................................... 20

5.3 Exposure to Aquatic Invasive Species Messaging ............................................................................. 21

5.4 Trust in Information Source .............................................................................................................. 22

5.5 Perceived Effectiveness of Clean, Drain, Dry Messaging .................................................................. 23

5.6 Message Experiment – Encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry ..................................................................... 25

5.7 Message Experiment – Perceived Severity of Aquatic Invasive Species ........................................... 27

5.8 Message Experiment – Message Influence on Clean, Drain, Dry ..................................................... 28

5.9 Frequency of Undertaking Clean, Drain, Dry .................................................................................... 31

5.10 Perceived Effectiveness of Clean, Drain, Dry .................................................................................. 32

5.11 Perceived Difficulty of Undertaking Clean, Drain, Dry .................................................................... 33

5.12 Perception of Other Boaters’ Clean, Drain, Dry Behavior ............................................................... 34

5.13 Expectation from Others to undertake Clean, Drian, Dry Behavior ............................................... 35

5.14 Perceived Obligation to Engage in Clean, Drain, Dry Behavior ....................................................... 36

5.15 Constraints to Undertaking Clean, Drain, Dry Behavior ................................................................. 37

5.16 Trust in State to Manage Aquatic Invasive Species ........................................................................ 38

5.17 Comparisons of Select Variable by Boater Characteristics ............................................................. 39

5.18 Message Treatment Follow-up Analyses ........................................................................................ 45

6.0 DISCUSSION & RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................................................... 47

7.0 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................... 53

iii

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Quagga Zebra Mussel Action Plan

implementation grant via the Invasive Species Action network (# 21-001A). We would also like to extend

our appreciation to Monica McGarrity and the members of the Education and Outreach Committee for

the Western Regional Panel on Aquatic Nuisance Species for their guidance and thoughtful feedback

throughout the conduct of this work.

iv

LIST OF TABLES

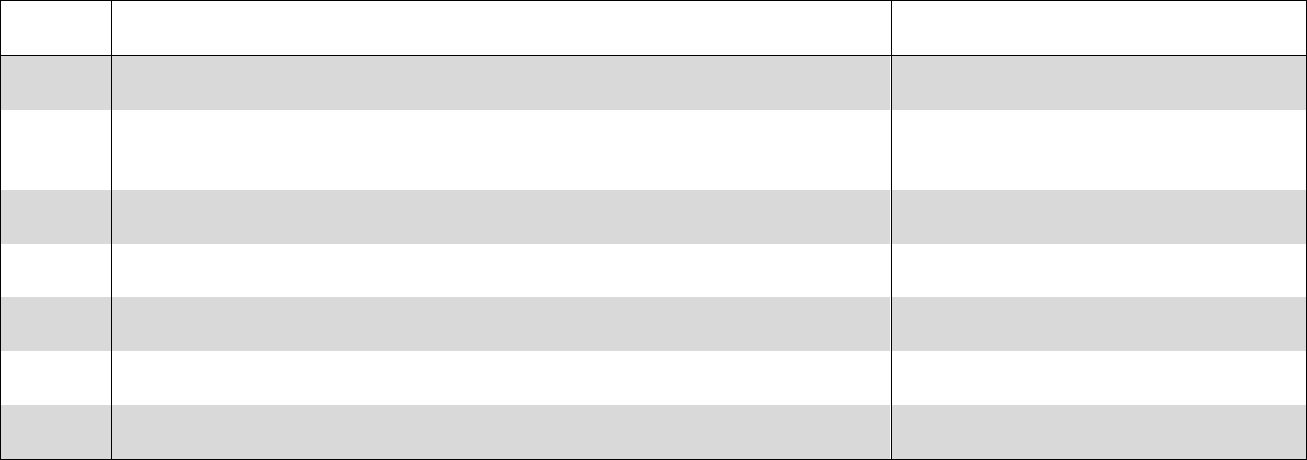

Table 1. Message Treatments ....................................................................................................................... 6

Table 2. Solicitation, Response, and Questionnaire Completion ................................................................ 10

Table 3. Manipulation Check Questions ..................................................................................................... 12

Table 4. Age Categories............................................................................................................................... 14

Table 5. Gender ........................................................................................................................................... 14

Table 6. Race ............................................................................................................................................... 14

Table 7. Education ....................................................................................................................................... 15

Table 8. Household Income ........................................................................................................................ 15

Table 9. Primary Boating State/Province .................................................................................................... 16

Table 10. State/Province of Primary Residence .......................................................................................... 17

Table 11. Watercraft Ownership................................................................................................................. 17

Table 12. Activity Preferences .................................................................................................................... 18

Table 13. Days Boating by Season............................................................................................................... 18

Table 14. Primary Waterbody ..................................................................................................................... 18

Table 15. Familiarity with AIS ...................................................................................................................... 19

Table 16. Attitudes Toward AIS ................................................................................................................... 20

Table 17. Information Source ..................................................................................................................... 21

Table 18. Trust in Source of Information about AIS .................................................................................... 22

Table 19. Perceived Effectiveness of Information Source .......................................................................... 24

Table 20. Message Effect on Clean Drain Dry ............................................................................................. 26

Table 21. Perceived Problem of AIS in State ............................................................................................... 27

Table 22. Message Influence on Clean, Drain, Dry Behavior ...................................................................... 29

Table 23. Statistical Variation Among Message Treatments ...................................................................... 30

Table 24. Frequency of Undertaking Clean, Drain, Dry .............................................................................. 31

Table 25. Effectiveness of Clean, Drain, Dry ............................................................................................... 32

Table 26. Perceived Difficulty of Clean, Drain, Dry ..................................................................................... 33

Table 27. Perception of Other Boaters’ Clean, Drain, Dry .......................................................................... 34

Table 28. Perception of Other Boaters’ Expectation of Me to Engage in Clean, Drain, Dry ....................... 35

Table 29. Personal Obligations to Engage in Clean, Drain, Dry .................................................................. 36

Table 30. Constraints to Engaging in Clean, Drain, Dry .............................................................................. 37

Table 31. Individual Behaviors - Constraints to Engaging in Clean, Drain, Dry ........................................... 37

Table 32. Trust in State to Manage AIS ....................................................................................................... 38

v

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Study Purpose

The overarching goal of this project was to collect and analyze data that would ultimately enhance the

long-term success of aquatic invasive species (AIS) prevention outreach campaigns across Western

Regional Panel (WRP) member states and member organizations by analyzing the effectiveness of

current and potential messaging and delivery methods to elicit desired behavior change from specific

demographics. However, the applicability of the results of this effort are not limited to the project’s

geographical area.

Design

• Thirty-one key informant interviews were conducted in the fall of 2021. Most informants had in

excess of 20 years of boating experience and occupied a professional or voluntary role in the

management of AIS in their communities. Analyses of the interview data provided some insight on

different AIS message content, message placement, and mode of delivery. These findings were

integrated into our survey questionnaire.

1. The survey questionnaire was comprised of series of items that explored an array of issues related

to boaters’ perceptions and actions related to AIS. It also included a messaging experiment where

respondents were assigned to one of 20 message treatments and requested to indicate the

message’s effectiveness for encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry. The survey questionnaire took

approximately 25 minutes to complete.

2. Three broad approaches were employed to contact potential respondents; 1) Texas A&M University

sending emailing solicitations to potential respondents in databases provided by participating states;

2) Participating states distributing a web-link to the questionnaire hosted by Texas A&M University

to their registered boater or licensed angler databases; and 3) states posting the web-link to the

questionnaire on their agency website.

3. The varied methods yielded 3,900 fully completed questionnaires.

Sample Profile

The survey sample was relatively homogenous and comprised mostly of White, older men (M=58 years),

residing in households with annual incomes in excess of $100,000. These demographics are consistent

with other surveys of registered boaters.

Findings

• Familiarity with AIS - Respondents reported being broadly aware of AIS and the need to Clean,

Drain, Dry. They were less familiar with specific species present in their state and locations

(waterbodies) of where they have been detected.

• Frequency of Clean, Drain, Dry - Respondents reported that they regularly Clean, Drain, and Dry their

boats prior to entering another waterbody. They are less inclined to wash their watercraft with a

pressure washer or hot water.

• Perceived Effectiveness of Clean, Drain, Dry - Actions related to cleaning, draining, and drying

respondents’ watercraft were considered most effective. Considered to be less effective was

washing watercraft with a pressure washer or hot water before entering another waterbody.

• Constraints to Clean, Drain, Dry - Twenty-five percent of respondents indicated facing some form of

a constraint to undertaking Clean, Drain, Dry. The absence of cleaning stations, crowding at boat

ramps, and skepticism over other boaters’ undertaking Clean, Drain, Dry were the most cited

reasons constraining their behavior.

vi

• Information about AIS - Boat ramp signage, state agency websites, and inspection station personnel

were the most commonly cited sources of information about AIS.

• Trust in Information Providers - State agency websites, boat ramp signage, inspection stations, and

conservation organizations were the most trusted sources of AIS information.

• Perceived Effectiveness of Information about AIS and Clean, Drain, Dry - Respondents were

requested to indicate which of the listed sources of information would be most effective at; a)

preventing the spread of AIS, b) encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry, and c) reaching the population of

boaters across the state. Boat ramp signage and state agency websites were considered to be most

effective for accomplishing all three outcomes. Alternately, while inspection stations were

considered to be effective for encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry, and preventing the spread of AIS, they

were somewhat limited in their ability to reach the population of boaters.

• Messaging Experiment to Encourage Clean, Drain, Dry - While no single treatment message was

statistically superior at encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry, seven messages scored highest. Their means

of 3.4 (on a 5-point scale) or greater indicate that respondents felt the messages would be

moderately to quite effective at increasing boaters’ Clean, Drain, Dry behavior. The messages were

designed around themes related to:

• Militaristic, nativist, protective, and science-based metaphors;

• Injunctive norms (i.e., encouraging the belief that other boaters expect them to Clean, Drain,

Dry); and

• Economic losses and ecological gains.

Messages that respondents considered least effective were focused on specific identities (i.e.,

hunter, boater, paddler) and a combination of descriptive and injunctive norms (i.e., other boaters’

expectation of them and the suggestion that other boaters conduct Clean, Drain, Dry).

Follow-up analyses exploring variation among select groups on the most effective message revealed

little variation.

Discussion/Conclusion

• Age was associated with awareness and knowledge of AIS and Clean, Drain, Dry behavior with older

boaters scoring higher. Messaging toward a younger cohort ought to occur early in their boating

careers. Beyond the most popular sources (i.e., boat ramps, state agency websites, and inspection

stations), these messages could be delivered with boat registration and fishing license renewals.

• Familiarity with AIS (prior to taking survey) was linked to the extent to which respondents interacted

with the resource (e.g., houseboat owners, tournament anglers, avid boaters). Those least familiar

with AIS reported (e.g., pontoon and sailboat owners, paddlers, hunters) less concern over AIS and a

lower likelihood of implementing Clean, Drain, Dry. Those most actively interacting with the

resource will likely encounter AIS messaging through the most popular sources of information (boat

ramp kiosks, state agency websites, inspection stations), whereas accessing infrequent boaters will

be an ongoing challenge. Point of sale for non-motorized watercraft (e.g., decals placed on the

watercraft) and hunting licenses provides one opportunity for agency contact.

• In terms of AIS information to which respondents had been previously exposed:

o Most common sources were boat ramp kiosks, followed by the state’s agency website, and then

inspection station personnel. For these information sources, respondents indicated that their

state’s agency websites were most trusted, followed by boat ramp kiosks, and then state

inspection personnel. AIS information should be easily accessible on agency websites. Given

their broad coverage and, importantly, boaters’ trust in the state to provide up to date

information about AIS, access to this information on agency websites should feature

prominently.

vii

o Younger (18-25) respondents were more likely to trust conservation organizations. Conservation

organizations provide an opportunity to develop strategic partners that can help amplify agency

efforts through social media, their agency websites, and through members’ social networks.

Regular active engagement with these partners would also assist in providing up to date

information.

o Similar to respondents’ exposure and trust, boat ramp signage, state agency websites, and state

inspection personnel were considered most effective for preventing the spread of AIS,

encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry, and reaching the population of boaters. Residents of states

utilizing inspection stations (e.g., California, Utah, Nevada) expressed greater trust in the

information provided by inspection station personnel, considered the information more

effective at preventing the spread of AIS, and more effective at encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry.

While the coverage of the information provided by inspection station personnel is

geographically limited, it is clearly a useful tool and one that warrants consideration/adoption.

• In terms of the messaging experiment:

o Overall, respondents considered the identity frames least effective compared to other frames at

encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry.

o Statistically, there was no significant variation among message treatments – all moderately

effective at encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry. Seven messages, however, were somewhat superior.

For future messaging efforts, agencies should consider elements of each message or in

combination when designing persuasive appeals. These include:

o All metaphor themes preformed comparatively well compared to other message

treatments. The science metaphor was the strongest performer in terms of

respondents’ reported effectiveness for encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry.

o Framing the impact of AIS on aquatic ecosystems (i.e., health in the absence of AIS) and

the state’s economic health (i.e., detriment with their presence) is compelling.

o Unlike the descriptive norm, the injunctive norm message attempts to instill a personal

obligation that rests on the perception of others’ expectations.

• Respondents indicated that they almost always engaged in cleaning and draining behaviors. They

indicated being less likely, however, to wash their boat with a pressure washer or hot water. Not all

boaters will have access to a pressure washer and washing watercraft with hot water is likely

perceived to be cumbersome. Cleaning stations with pressure washers or hot water would help to

address this issue.

• The installation of cleaning stations with clearly visible messaging kiosks would help negate the

perception that few undertake Clean, Drain, Dry by providing evidence of others taking action. The

more boaters are seen to be engaging in these actions, the more normative the behavior becomes.

1

1.0 INTRODUCTION

The overarching goal of this project was to collect and analyze data that would ultimately enhance the

long-term success of aquatic invasive species (AIS) prevention outreach campaigns across Western

Regional Panel (WRP) member states and member organizations by analyzing the effectiveness of

current and potential messaging and delivery methods to elicit desired behavior change from specific

demographics. However, the applicability of the results of this effort are not limited to the project’s

geographical area.

Objective 1: Evaluate and quantify the effectiveness of WRP states’ campaign messaging, current and

potential, alone or in combination, in eliciting the desired AIS prevention behavior among boaters (e.g.,

pull drain plugs, do not launch for a specific period of time, remove vegetation, don’t dump bait, etc.)

for specific boating and boater demographics. The focus will be placed on high-risk recreational user

groups, in accordance with guidance from the WRP Education Outreach Committee (EOC). Past, current,

and future behaviors were evaluated.

Objective 2: Evaluate and quantify the effectiveness of delivery methods currently used–or that could

potentially be used–by WRP states to elicit desired AIS prevention behaviors for specific boating and

boater demographics.

Objective 3: Provide a summary report/publication on the effectiveness of current and past WRP states’

public outreach campaigns’ messaging and delivery methods and recommendations on how to most

effectively tailor campaigns to elicit specific AIS prevention behaviors overall and for specific

recreational user groups and demographics which includes:

• analysis of the effectiveness of WRP states’ messaging

• analysis of the effectiveness of implemented delivery methods

• recommendations on specific messaging that may be most effective

• recommendations on delivery methods that may be most effective for different demographics

• recommendations on other important considerations on how to effectively elicit specific AIS

prevention behaviors

2

2.0 BACKGROUND

Humans have had enormous impacts on earth and its biodiversity and many of these effects are global.

Lakes and streams are particularly prone to species loss (Ricciardi & Rasmussen, 1999), with the greatest

threats coming from land use changes and exotic invasive species (“biotic exchange”, Sala et al., 2000).

Humans have been particularly effective in breaking down biogeographic barriers through long-distance

trade, intentionally introducing some species and carrying others as hitchhikers (Kolar & Lodge, 2000).

The result has been a translocation of numerous freshwater species (Hulme, 2009). Although most

introduced species fail to establish and spread (Williamson, 1996), many freshwater species have

become invasive and some have caused widespread environmental effects and economic harm

(Pimentel et al., 2005).

Freshwater ecosystems have greater biodiversity per surface area than marine and terrestrial

ecosystems (Dudgeon et al., 2006; Balian et al., 2008). Freshwater ecosystems also play an active role in

nutrient and water cycling (Wetzel, 2001), which translate into goods and services for human societies.

At the same time, freshwater ecosystems have been deeply transformed by invasive species from a wide

variety of taxonomic groups (Strayer, 2010; Simberloff et al., 2013). It is thus vital to understand the

factors that govern the introduction, spread, and subsequent impacts of invasive species in these

ecosystems.

Recreational boating can significantly contribute to the rapid spread of AIS by unintentionally

transporting species attached to hulls, props, and other submerged components attached to the

watercraft, as well boat live wells or any other water-bearing compartments. Boaters often travel long

distances for recreation in different freshwater bodies and can be a significant vector for spreading AIS

between inland waters (Johnson et al., 2001; Robertson et al., 2020; Rothlisberger et al., 2010). This fact

highlights the crucial role boaters’ preventive behavior can play in controlling and reducing AIS high

economic and ecological impacts. Cleaning, draining, and drying watercraft is recognized as the key

desired boater behavior for AIS spread prevention and “Clean, Drain, Dry” is a central message in AIS

outreach at a national scale.

Despite the significance of their role in controlling and managing the spread of AIS, our understanding of

boaters’ preventive behavior and the impact of possible interventions to alter behavior is, in large part,

restricted to insights gleaned from studies conducted in the Eastern and Great Lakes states. Among

these studies, several have explored the effectiveness of various outreach and communication

strategies. For instance, Wallen and Kyle (2018) found that regulation-framed messages emphasizing the

law and the possibility of fines outperformed messages referring to the norms of compliance with Clean,

Drain, Dry. The results from Sharp et al.'s (2017) study also revealed the importance of educational

programs tailored to specific recreational uses and recreational settings in compliance with preventive

measures. Moreover, Witzling et al. (2016) and Witzling et al. (2015) evaluated the effectiveness of

different communication channels and found that signs posted at boat ramps, interpersonal

communications, information provided by lake associations, and direct communication between natural

resource managers and boaters can all be effective to varying degrees when messaging is tailored to

different groups of boaters. These findings highlight the need for communication strategies to be multi-

modal in terms of the distribution of AIS information to improve the likelihood of message exposure and

targeted toward different boating and aquatic recreation use groups.

3

Another line of research has revealed the relationship between socio-psychological factors and boater

intentions, and preventive pro-environmental behavior. These studies have shown psychological drivers

such as norms (personal and social), the ascription of responsibility, a concern for the environment and

threats to its health, and value orientations can all shape boaters’ willingness to engage in pro-

environmental behavior that mitigates the threat of AIS (Kemp et al., 2017; Pradhananga et al., 2015;

van Riper et al., 2019). Similarly, those who felt greater responsibility and a moral obligation to prevent

the spread of ANS reported engaging in preventive measures more often (Beardmore, 2015; Mayer et

al., 2015; Seekamp et al., 2016). Also, the more likely boaters were to express concern for

environmental protection and an understanding of the risks posed by the spread of AIS, the more likely

they were to report adopting preventive action (Connelly et al., 2016; Pavloski et al., 2019; Pradhananga

et al., 2015). Moreover, boaters’ perception of what their peers do and significant others expect them to

do influences their behavior (Connelly et al., 2016; Wallen & Kyle, 2018; Witzling et al., 2015). Other

studies have also investigated the relationship between the public’s awareness and knowledge of ANS

and their behavior. The findings, generally, demonstrate that residents, especially those who participate

in water-based recreation, are supportive of actions to minimize the effects of AIS when they are aware

of the negative consequences (e.g., Eiswerth et al., 2011; Fouts et al., 2017; Sharp et al., 2017).

There is research, however, that reveals a mismatch between boaters’ AIS awareness and support for

preventive measures and their willingness to adopt mitigation behavior (Cole et al., 2016; Connelly et

al., 2016; Mueting & Gerstenberger, 2011). For instance, Cole et al. (2016) found that raising awareness

and knowledge is a necessary but insufficient condition for the adoption of ANS prevention behaviors.

Their results illustrate that awareness of AIS spread and its impact on aquatic ecosystems does not

necessarily relate to an agency’s investment in outreach (Cole et al., 2016). Similarly, Connelly et al.

(2016) and Ventura et al. (2017) found that despite high awareness and stated support, boaters were

less frequently conducting difficult preventive actions, such as drying and disinfecting, rinsing equipment

with hot water, or using high-pressure washing. These findings highlight often reported gaps between

individuals’ awareness of environmental issues and appropriate action. These knowledge/awareness-

action gaps necessitate outreach efforts focusing on strategies that facilitate behavior and remove

barriers (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002; Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Steg et al., 2014).

Last, research on the barriers to engagement in pro-environmental behavior has also revealed that

regardless of environmental concern, they have the potential to significantly constrain intent and action

(Cleveland et al., 2020; Moghimehfar & Halpenny, 2016; Tanner, 1999). Broadly, two categories of

constraints to pro-environmental action have been identified in the literature; subjective and objective

(Tanner, 1999). Findings illustrate that objective constraints, such as time, the availability of facilities,

space limitations, cost, and convenience hinder pro-environmental action (Lorenzoni et al., 2007;

Moghimehfar & Halpenny, 2016). However, there is evidence suggesting that subjectively perceived

barriers (e.g., perceived costliness, perceived ineffectiveness) are a more compelling obstacle for

adopting pro-environmental action (Cleveland et al., 2020; Steg et al., 2014). In the context of

preventing the spread of ANS, boater misconceptions on subjectively defined constraints related to

perceived cost, effort, and effectiveness can negatively impact their willingness to adopt mitigation

measures (Connelly et al., 2016; Ventura et al., 2017).

4

3.0 STUDY DESIGN AND METHOD

3.1 Key Informant Interviews

Thirty-one key informant interviews were conducted with boaters from Arkansas (3), California (4),

Kansas (3), North Dakota (1), Nevada (2), South Dakota (2), Texas (4), Utah (8) and Washington (4). State

AIS coordinators provided informants’ contact information. Key informants are “particularly

knowledgeable and articulate – people whose insights can prove particularly useful in helping the

observer understand what is happening” (Patton, 1990). The key informant interviews were conducted

to ensure that we were not missing content that would be crucial in the development of our survey

questionnaire. The interview guide is provided in Appendix A1.

Most informants had in excess of 20 years of boating experience and occupied a professional or

voluntary role in the management of AIS in their communities. Analyses of the interview data provided

some insight on different AIS message content, message placement, and mode of delivery. These

findings were integrated into our survey questionnaire.

3.2 Survey Questionnaire

The survey questionnaire was comprised of series of items that explored an array of issues related to

boaters’ perceptions and actions related to AIS and as arranged in six sections (see Appendix A3):

4. Watercraft ownership and use history;

5. Knowledge and awareness of aquatic invasive species;

6. AIS messaging awareness and preferences;

7. AIS messaging experiment;

8. Clean, drain, dry behavior, perceived effectiveness, perceived difficulty, and perceived

prevalence; and

9. Socio-demographic characteristics.

For the AIS messaging experiment, respondents were presented with one of 20 messages and asked a

series of questions about their perception on whether or not the image would impact Clean, Drain Dry

behavior (See Table 1 and Appendix A3). The message treatments were structured around eight themes

all focused on promoting Clean, Drain, Dry behavior plus a control:

1. A control message with a basic Clean, Drain, Dry statement.

2. The control in addition to the “Stop Aquatic Hitchhikers” branding.

3. The control in addition to statement about Clean, Drain, Dry being required by law.

4. The control in addition to four treatments focused on respondents’ identity as a;

a. Boater,

b. Paddler,

c. Hunter, and

d. Angler.

5. The control in addition to four treatments examining ecological and economic gains and losses.

6. The control in addition to three treatments examining norms associated with Clean, Drain, Dry

behavior;

a. Injunctive – Individual perceptions of what boaters ought to do,

b. Descriptive – Individual perceptions of what other boaters are doing, and

c. Combination of injunctive and descriptive norm messaging.

5

7. The control in addition to four metaphor-themed messages focused on;

a. Science,

b. Protection/nurturing,

c. Nativist, and

d. Militaristic.

8. The control in addition to a messaging informing boaters they are entering a lake with AIS.

9. The control in addition to a message indicating boaters need to Clean, Drain, Dry their

watercraft after leaving every lake, every time.

The treatments focused on identity were drawn from the work of Fielding and associates’ work on social

identity and its association conservation-related behaviors (Fielding & Hornsey, 2016; Schultz & Fielding,

2014; Unsworth & Fielding, 2014). This work reveals the extent to which identity salience and the

norms associated with the identity gird pro-environmental behavior. The environment and economic

gain/loss scenarios were drawn from Degolia, et al.’s (2019) related to wild pig management. Their work

revealed that messages framed in terms of environmental outcomes, as opposed to economic, elicited

more support for AIS management among a sample of California residents. Also, messages referencing

economic and environmental loss drove stronger support for invasive species management compared to

messages referencing gain. Normative message frames were drawn from the work of Wallen and Kyle

(2018). Metaphor themed frames were drawn from Shaw, Campbell, and Radler (2021). These

metaphors touched upon themes related to; a) science with objective, fact-based information, b) the

protection of nature with a nurturing statement related to protecting the environment, c) non-nativist

with reference to alien species, and d) militaristic with reference to battles against invasives.

6

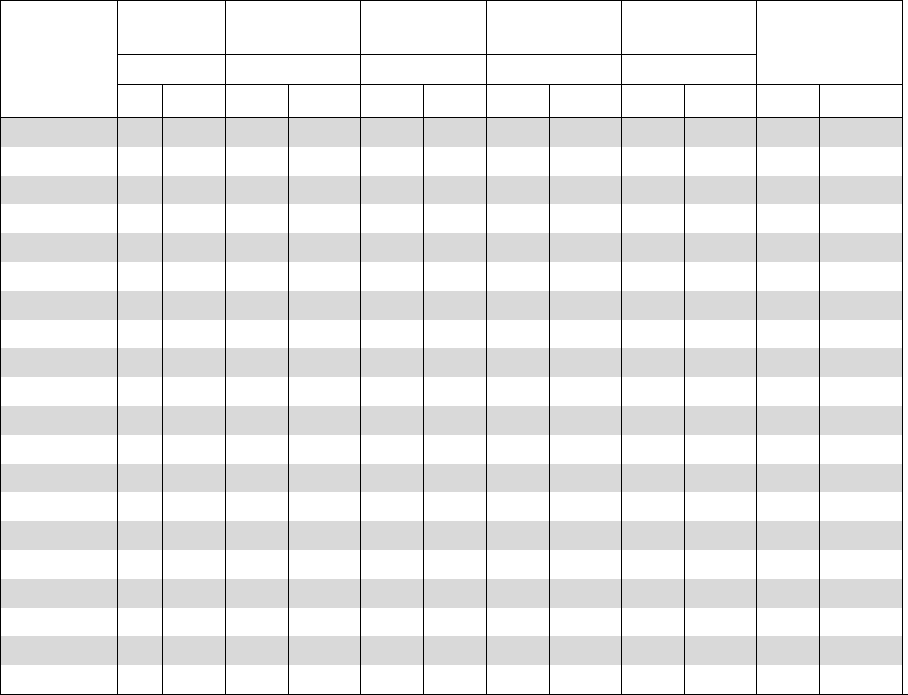

Table 1. Message Treatments

Treatment

Theme

Message

Image

Header

Footer

1

Baseline/Control

Clean, Drain, Dry

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

2

Stop aquatic

hitchhikers branding

Stop aquatic hitchikers brand logo

Logo

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

3

Legal

IT’S THE LAW.

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY YOUR BOAT

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

4

Identity

BOATERS - DO YOUR PART

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY YOUR BOAT

Motorboat

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

5

PADDLERS - DO YOUR PART

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY YOUR BOAT

Paddlers

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

6

HUNTERS - DO YOUR PART

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY YOUR BOAT

Hunters

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

7

ANGLERS - DO YOUR PART

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY YOUR BOAT

Anglers

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

Loss/Gain

8

Ecological Loss

PROTECT YOUR WATERS.

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY.

Our aquatic ecosystems will

suffer tremendously

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

9

Ecological Gain

PROTECT YOUR WATERS.

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY.

Our aquatic ecosystems will

benefit tremendously

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

10

Economic Loss

PROTECT YOUR WATERS.

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY.

It will cost our state (YOU) $

millions

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

11

Economic Gain

PROTECT YOUR WATERS.

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY.

It saves our state (YOU) $ millions

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

7

Table 1 (continued). Message Treatments

Treatment

Theme

Message

Image

Header

Footer

Norms

12

Descriptive

PROTECT YOUR WATERS.

The MAJORITY of the state’s

boaters CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY their

boats

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

13

Injunctive

PROTECT YOUR WATERS.

the state’s boaters EXPECT you to

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY your boat

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

14

Descriptive/injunctive

PROTECT YOUR WATERS.

The MAJORITY of the state’s

boaters EXPECT you to CLEAN,

DRAIN, DRY your boat

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

Metaphors

15

Science

PREVENT THE SPREAD OF

AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES.

Aquatic invasive species are

present in our state’s lakes and

rivers and can severely impact

these ecosystems

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

16

Protective/Nurturing

HELP PROTECT OUR WATERS.

Aquatic invasive species harm our

lakes and rivers.

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

17

Nativist

NOT NATIVE, NOT WELCOME

Keep aquatic invasive species out

of our state’s lakes and rivers

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

18

Militaristic

STOP THE INVASION OF AQUATIC

INVASIVE SPECIES

Help fight the battle again aquatic

invasive species

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

8

Table 1 (continued). Message Treatments

Treatment

Theme

Message

Image

Header

Footer

19

Entering

You are entering a lake that has

AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES.

Be sure you CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY

before re-entering another

waterbody

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

20

Every lake, every

time

Every lake, every time

Different

boater types

ATTENTION

Clean, Drain, Dry

9

3.3 Data Collection

Respondents’ access to the questionnaire utilized multiple solicitation modes. The different methods of

solicitation are displayed in Table 2 below. Three broad approaches were employed:

1. For solicitations management by TAMU, respondents were sent an email with an individualized

URL. Two additional email reminders/thank you notes were sent four days apart.

2. For agencies electing to distribute a URL to their registered boaters of licensed anglers, multiple

approaches were employed; 1) email a single URL and email a follow-up thank you reminder, 2)

post a weblink on their agency website, and 3) promote the URL on the agency’s social media

(Facebook, Twitter).

3. States posted a URL weblink on their agency website.

Collectively, 8,135 recipients of the solicitation initiated the questionnaire. The first question

respondents encountered asked if they had boated in freshwater in the previous 12 months. Only those

answering “yes” proceeded with the questionnaire; 6,393 responded “yes”. Of these, 3,900 completed

all questions. For our AIS messaging experiment, Qualtrics® randomly assigned each respondent to one

of the 20 message treatments. Responses to each treatment ranged between 201 to 226 responses.

10

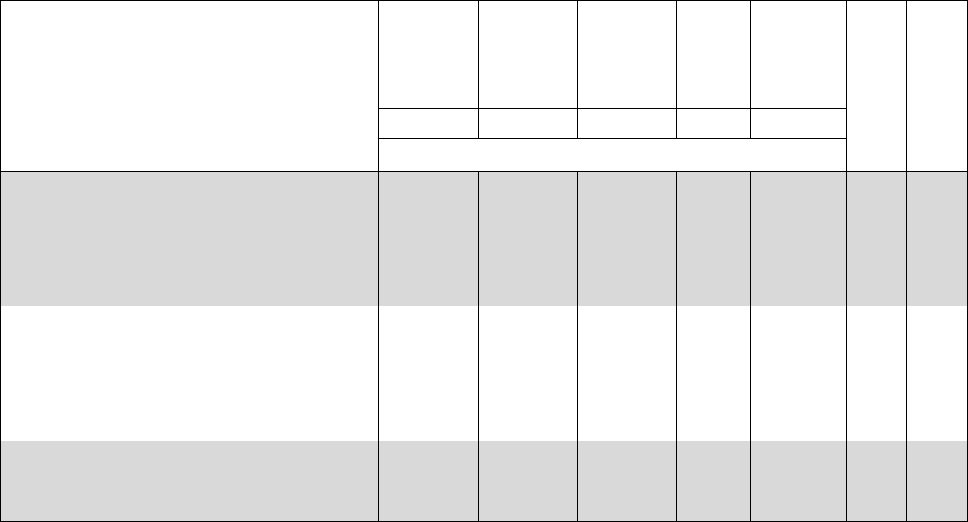

Table 2. Solicitation, Response, and Questionnaire Completion

State/Province

Email Invitation Sent by TAMU

Email Invitation Sent by State

Weblink Posted on

State Agency Website

Sent

a

Initiated

b

Complete

c

Sent

a

Initiated

b

Complete

c

Initiated

Complete

Alaska

1

126,082

2,332

573

Arizona

2

13

8

California

3

464

332

Colorado

4

48

39

Hawaii

5

4

3

Idaho

6

24

16

Kansas

7

10,000

1,313

942

Montana

8

400

24

16

Nevada

9

100

97

Nebraska

10

2

2

New Mexico

11

1

1

North Dakota

12

4

2

Oklahoma

13

10,000

203

65

Oregon

14

10,000

1,007

548

South Dakota

15

5

3

Texas

16

10,000

939

527

Utah

17

8,000

1,590

1,040

Washington

18

10,000

52

47

Wyoming

19

10

9

11

a

Weblink sent to respondents.

b

Respondents clicking on weblink to commence completing the questionnaire.

c

Full completion of the questionnaire.

1

Email sent to hunting and fishing license holders purchased in 2019 and 2020.

2

Did not post weblink. Respondents reported residing outside of AZ but boat in AZ.

3

State weblink was included in an “angler update” promotional/information email distributed to

licensed anglers in additional to sharing on the Division of Boating and Waterway’s Facebook Page.

4

Weblink on agency website promoted through Colorado Department of Natural Resources social

media.

5

Twelve boaters were approached at a fishing club on Wahiawa Reservoir.

6

Link placed on websites for Idaho Parks and Recreation Department, Idaho Department of Agriculture,

and Invasive Species of Idaho.

7

An email invitation and additional reminder was sent to a random sample of registered boaters.

8

Three email invitations sent four days apart.

9

Weblink on agency website promoted through Nevada Department of Wildlife social media. Two email

solicitations sent to motorized and non-motorized boaters who had purchased an AIS decal.

10

Did not participate.

11

Did not participate.

12

Weblink posted on agency website.

13

Three email invitations sent four days apart.

14

Three email invitations sent four days apart.

15

Weblink posted on agency website.

16

Three email invitations sent four days apart.

17

Link distributed by Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. Link also promoted on agency Facebook page

and distributed with flyers.

18

Email invitation sent to licensed anglers.

19

Link placed on Wyoming Game and Fish Department website.

12

3.4 Message Experiment - Manipulation Check

For our AIS messaging experiment, to ensure respondents had read and accurately processed the content of each image, respondents were

requested to answer two questions;

1. What does this message tell you about Clean, Drain, Dry behaviors? and

2. What do you think is the intent of this message?

Responses to the first question were tailored around the content of each image/message and are displayed in Table 3. The response choice for

the question was a dichotomous “yes/no” with “yes” being the correct answer. For the second question, respondents were again requested to

answer “yes/no” to the question with “yes” also being the correct answer. If respondents answered “no” to either question, they were removed

from the analyses. Four hundred and six respondents were removed from the analyses.

Table 3. Manipulation Check Questions

Message

What does this message tell you about Clean, Drain, Dry behaviors?

a

What do you think is the intent of this

message?

a

1

[state] boaters should clean, drain, and dry their boats and equipment before

entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

2

To prevent the spread of aquatic invasive and stop aquatic hitchhikers, [state]

boaters should clean, drain, and dry their watercraft and equipment before entering

another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

3

Cleaning, draining, and drying your watercraft and equipment is required by [state]

law.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

4

It is a boater’s responsibility to clean, drain, and dry their watercraft and equipment

before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

5

It is a paddler’s responsibility to clean, drain, and dry their watercraft and

equipment before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

6

It is a hunter’s responsibility to clean, drain, and dry their watercraft and equipment

before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

7

It is an angler’s responsibility to clean, drain, and dry their watercraft and

equipment before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

13

Table 3 (continued). Manipulation Check Questions

Message

What does this message tell you about Clean, Drain, Dry behaviors?

a

What do you think is the intent of this

message?

a

8

The [state]’s aquatic ecosystems will suffer if [state] boaters do not clean, drain, and

dry their watercraft and equipment before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

9

The [state]’s aquatic ecosystems will benefit from [state] boaters cleaning, draining,

and drying their watercraft and equipment before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

10

If [state] boaters fail to adopt clean, drain, and dry behaviors it will cost the state

millions of dollars to mitigate damage from aquatic invasive species

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

11

If [state] boaters fail to engage in clean, drain, and dry behaviors it will save the

state millions of dollars from having mitigate damage from aquatic invasive species

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

12

The majority of [state] boaters clean, drain, and dry their watercraft and equipment

before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

13

[state] boaters expect you to clean, drain, and dry your boat and equipment before

entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

14

The majority of [state] boaters expect you to clean, drain, and dry your watercraft

and equipment before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

15

Aquatic invasive species negatively impact [state] ecosystems and to prevent their

spread you should clean, drain, and dry your watercraft and equipment before

entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

16

To protect [state] waters, you should clean, drain, and dry your watercraft and

equipment before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

17

Aquatic invasive species are neither native or welcome in [state] and you need to

clean, drain, and dry your watercraft and equipment before entering another

waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

18

To prevent the invasion of aquatic invasive species in [state], you need to clean,

drain, and dry your watercraft and equipment before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

19

You are about to enter a lake with aquatic invasive species and need to clean, drain,

and dry your watercraft and equipment before entering another waterbody.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

20

You need to clean, drain, and dry your watercraft and equipment after leaving every

lake, every time.

To encourage, clean, drain dry behaviors

among [state] boaters.

a

Responses choice for both questions; Yes/No

14

4.0 SAMPLE PROFILE

Respondents were predominantly White (85.2%; Table 6), older (M=54.99) men (85.8%; Table 5). They

were relatively well educated with most having at least vocational school educational training or two-

year college (83.5%: Table 7) and residing in households with moderately high annual incomes (61.6%

earning > $100,000; Table 8).

Table 4. Age Categories

Table 5. Gender

Table 6. Race

n

%

18-25

28

.7

26-35

136

3.5

36-45

486

12.5

46-55

854

21.9

56-65

1256

32.2

66-75

923

23.7

> 75

217

5.6

Total

3900

100.0

n

%

Prefer not to answer

130

3.3

Female

420

10.8

Male

3346

85.8

Nonbinary

4

.1

Total

3896

100.0

n

%

Asian

42

1.0

Spanish/Hispanic/Latino

89

2.2

White

3447

85.2

American Indian/Alaska Native

102

2.5

Black/African American

24

.6

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

18

.4

Middle Eastern

9

.2

Prefer not to Answer

226

5.6

Other

91

2.2

Total

4048

100.0

15

Table 7. Education

Table 8. Household Income

n

%

Less than high school

32

.8

High school graduate

611

15.7

Vocational/trade school Two-year college

1031

26.4

Four-year college

1366

35.0

Graduate degree

860

22.1

Total

3900

100.0

n

%

Prefer not to answer

131

3.4

Under $20,000

83

2.1

$20,000-$39,999

159

4.1

$40,000-$59,999

271

6.9

$60,000-79,999

421

10.8

$80,000-$99,999

434

11.1

$100,000-$119,999

530

13.6

$120,000-$139,999

381

9.8

$140,000-$159,999

334

8.6

$160,000 and above

1156

29.6

Total

4048

100.0

16

Respondents’ state of residence (Table 10) and primary boating state/province (Table 9) tracked along

response rates reflected in Table 2.

Table 9. Primary Boating State/Province

n

%

British Columbia

1

.0

Nunavut

1

.0

Alaska

505

12.9

Arizona

12

.3

Arkansas

4

.1

California

305

7.8

Colorado

20

.5

Hawaii

3

.1

Idaho

33

.8

Kansas

822

21.1

Minnesota

6

.2

Missouri

31

.8

Montana

21

.5

Nebraska

3

.1

Nevada

57

1.5

New Mexico

1

.0

North Dakota

1

.0

Oklahoma

75

1.9

Oregon

508

13.0

South Dakota

3

.1

Texas

484

12.4

Utah

950

24.4

Washington

39

1.0

Wyoming

15

.4

Total

3900

100.0

17

Table 10. State/Province of Primary Residence

The most commonly owned watercraft reported by respondents were ski/wakeboard boats (17.1%;

Table 11), followed by kayak/canoes (15.7%), other (13.6%), and bass boats (13.3%).

Table 11. Watercraft Ownership

n

%

Alberta

1

.0

Alaska

510

13.1

Arizona

8

.2

California

297

7.6

Colorado

34

.9

Hawaii

3

.1

Idaho

15

.4

Kansas

878

22.5

Montana

15

.4

Nebraska

2

.1

Nevada

72

1.8

New Mexico

1

.0

North Dakota

2

.1

Oklahoma

59

1.5

Oregon

501

12.8

South Dakota

2

.1

Texas

495

12.7

Utah

955

24.5

Washington

42

1.1

Wyoming

8

.2

Total

3900

100.0

n

%

Pontoon

455

7.2

Johnboat

555

8.8

Bass boat

836

13.3

Houseboat

132

2.1

Ski/Wake board

1080

17.1

Sailboat

122

1.9

Cabin Cruiser

181

2.9

Jet ski

435

6.9

Center console

336

5.3

Kayak/Canoe

988

15.7

Paddleboard

326

5.2

Other

855

13.6

Total

6301

100.0

18

Recreational fishing (44.0%; Table 12), pleasure cruising (27.7%), and wake sports (14.7%) were

respondents’ most favored activities.

Table 12. Activity Preferences

Summer (M=9.07 days; Table 13) was the most popular boating season.

Table 13. Days Boating by Season

Respondents indicated that lakes (77.5%; Table 14) were the freshwater waterbody they used most

often.

Table 14. Primary Waterbody

Respondents had extensive boating experience, reporting almost 19 years of boating experience

(M=18.76 years).

n

%

Recreational Fishing

2804

44.0

Tournament Fishing

168

2.6

Wake Sport

935

14.7

Pleasure Cruising

1729

27.2

Hunting

465

7.3

Other

267

4.2

Total

6368

100.0

Spring

Summer

Fall

Winter

M

4.93

9.07

5.40

1.30

SD

5.25

6.88

5.40

3.10

n

%

Lake

3022

77.5

River/Bayou

636

16.3

Offshore Ocean

30

.8

Inshore Bay

147

3.8

Private waterbody

65

1.7

Total

3900

100.0

19

5.0 STUDY FINDINGS

5.1 Familiarity with Clean, Drain, Dry

Respondents were most familiar with the with the need for boaters to engage in Clean, Drain, Dry before entering different waterbodies (item b,

M=4.58; Table 15). They were least familiar with the locations where AIS had been detected in their state (item d, M=3.54).

Table 15. Familiarity with AIS

Item

Not at all

familiar

Somewhat

familiar

Very

Familiar

M

SD

1

2

3

4

5

%

a. How familiar were you with aquatic invasive species

before taking this survey?

2.1 4.6 24.1 26.7 42.5 4.03 1.02

b. How familiar are you with the need for watercraft

users to clean their boats and equipment, drain all

water from the watercraft (e.g., bilges, ballasts), and

dry before entering another waterbody?

1.1 1.8 7.9 16.4 72.8 4.58 .80

c. How familiar are you with the aquatic invasive species

that have been detected in [state]?

4.0 8.8 27.3 26.2 33.6 3.77 1.13

d. How familiar are you with the locations (waterbodies)

where aquatic invasive species have been detected in

[state]?

7.8 11.3 28.7 23.3 28.8 3.54 1.23

e. How familiar are you with the problems caused by

aquatic invasive species in [state]?

2.2 4.6 19.6 26.7 46.9 4.12 1.02

20

5.2 Awareness and Concern over Aquatic Invasive Species

In terms of respondents’ awareness and concern over AIS (Table 16), most concern was expressed over the importance of preventing the spread

of aquatic invasives (Item h, M=4.73) and engaging in Clean, Drain, Dry behavior (item g, M=4.66).

Table 16. Attitudes Toward AIS

Item

Not at all

Somewhat

Significant

M

SD

1

2

3

4

5

%

a. How common are AIS (in primary boating state)?

.9

8.8

32.7

33.2

24.4

3.71

.96

b. How much of a problem are AIS (in primary boating state)?

1.1

8.0

32.2

33.1

25.7

3.74

.96

c. How much of a threat do AIS pose to the economy (of

primary boating state)?

1.3 7.0 24.6 31.0 36.1 3.94 1.00

d. How much of a threat do AIS pose to the health of

freshwater lakes and rivers (in primary boating state)?

.5 2.5 13.1 25.5 58.4 4.39 .84

e. How much of a threat do AIS pose to the health of

freshwater fish and wildlife (in primary boating state)?

.6 2.9 13.9 25.6 57.0 4.35 .87

f. How much of a threat do AIS pose to freshwater recreation

(in primary boating state)?

.8 4.4 16.6 26.9 51.3 4.24 .93

g. How important is removing plants/mud/organisms, draining

water from boat/compartments, drying completely?

.5 1.6 5 16.8 76.1 4.66 .70

h. How important do you think it is to prevent the spread of

aquatic invasive species?

.3 .9 4.2 14.5 80.1 4.73 .61

21

5.3 Exposure to Aquatic Invasive Species Messaging

Respondents were asked to indicate where they had received information about AIS in their state (Table

17). They were instructed to check all that apply. The most commonly reported source of information

was obtained at boat ramps or other signage (17.0%), followed by state agency websites (13.4%), and

then inspection station personnel (8.3%).

Table 17. Information Source

Information Source

n

%

Billboard

1022

5.9

Boat captain or fishing guides

354

2.0

Boat ramp or other signage

2957

17.0

Boating event (e.g., sailing regatta)

105

.6

Boating or fishing show

736

4.2

Conference, Meeting

120

0.7

Conservation organization

1110

6.0

Fishing Group

807

4.6

Fishing Tournament

194

1.1

Friends or Family

886

5.1

Inspection station personnel

1441

8.3

Internet search ads (e.g., Google)

433

2.5

Lake/homeowners association

348

2.0

Magazine

855

4.9

Newsletter

485

2.8

Newspaper

585

3.4

Other boaters

869

5.0

Radio

313

1.8

State agency website

2329

13.4

Other website

512

2.9

State social media

780

4.5

Other social media (e.g., fishing clubs)

454

2.6

TV

591

3.4

Other

238

1.4

Total

18524

100.0

22

5.4 Trust in Information Source

Respondents reported that the most trusted source of information (Table 18) came from state agency

websites (20.0%), followed by information at boat ramps or other signage (14.4%), and then inspection

station personnel (11.6%).

Table 18. Trust in Source of Information about AIS

Information Source

N

%

Billboard

313

2.3

Boat captain or fishing guides

374

2.7

Boat ramp or other signage

1970

14.4

Boating event (e.g., sailing regatta)

98

.7

Boating or fishing show

452

3.3

Conference, Meeting

167

1.2

Conservation organization

1236

9.0

Fishing Group

542

4.0

Fishing Tournament

134

1.0

Friends or Family

364

2.7

Inspection station personnel

1589

11.6

Internet search ads (e.g., Google)

226

1.7

Lake/homeowners association

205

1.5

Magazine

336

2.5

Newsletter

439

3.2

Newspaper

434

3.2

Other boaters

351

2.6

Radio

230

1.7

State agency website

2798

20.5

Other website

164

1.2

State social media

686

5.0

Other social media (e.g., fishing clubs)

199

1.5

TV

246

1.8

Other

110

.8

Total

13663

100.0

23

5.5 Perceived Effectiveness of Clean, Drain, Dry Messaging

Respondents were requested to indicate how effective they considered information on AIS for; a)

preventing the spread AIS, b) encouraging the adoption of Clean, Drain, Dry behaviors, and c) reaching

the population of boaters from across the state (Table 19).

For preventing the spread of AIS, boat ramp or other signage was considered to be most effective

(29.2%), followed by state agency websites (17.7%), and then inspection station personnel (16.1%).

With regard to the information source’s impact on the adoption of Clean, Drain, Dry behaviors, boat

ramp or other signage was again considered to be most effective (33.5%), followed by inspection station

personnel (18.9%), and then stage agency websites (11.5%).

Last, with regard to reaching the state’s population of boaters, boat ramp or other signage was

considered to be most effective (27.6%), followed by state agency websites (15.6%), and then television

(7.5%).

24

Table 19. Perceived Effectiveness of Information Source

Information Source

Preventing the spread

of AIS

Encouraging the adoption of

Clean, Drain, Dry Behaviors

Reaching the

Population of Boaters

n

%

n

%

n

%

Inspection station personnel

629

16.1

739

18.9

407

.4

Newspaper

34

.9

25

.6

40

1.0

TV

173

4.4

169

4.3

292

7.5

Radio

48

1.2

49

1.3

85

2.2

Newsletter

66

1.7

66

1.7

128

3.3

State social media

149

3.8

129

3.3

235

6.0

Other social media (e.g., fishing clubs)

77

2.0

98

2.5

154

3.9

Internet search ads (e.g., Google)

53

1.4

44

1.1

66

1.7

Magazine

16

.4

10

.3

26

.7

State agency website

691

17.7

447

11.5

608

15.6

Other website

10

.3

10

.3

15

.4

Other boaters

79

2.0

108

2.8

69

1.8

Billboards

149

3.8

135

3.5

240

6.2

Boat captains or fishing guides

34

.9

31

.8

27

.7

Boat ramp or other signage

1138

29.2

1305

33.5

1077

27.6

Fishing groups

103

2.6

116

3.0

88

2.3

Conservation organizations

211

5.4

159

4.1

114

2.9

Friends or family

33

.8

76

1.9

28

.7

Lake/homeowners association

41

1.1

36

.9

20

.5

Fishing Tournament

11

.3

12

.3

8

.2

Boating event (e.g., sailing regatta)

5

.1

5

.1

5

.1

Conference, meetings

7

.2

4

.1

2

.1

Boating or fishing show

57

1.5

48

1.2

59

1.5

Other

86

2.2

79

2.0

107

2.7

Total

3900

100.0

3900

100.0

3900

100.0

1=Not at all effective through 5=Extremely effective.

25

5.6 Message Experiment – Encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry

Respondents were presented with one of 20 messages and asked a series of questions about their

perception of whether or not the image would impact Clean, Drain, Dry behavior (See Appendix A3). The

messages were randomly assigned across the population of respondents. After being presented with the

message, respondents were then requested to respond to a series of questions concerning their; a)

perceptions of the message’s effectiveness for encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry behavior, b) raising their

concern over AIS, and c) the likelihood they would engage in Clean, Drain, Dry behavior on their next

boating trip.

We conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA; When there was equality among the variances we used

Tukey’s post hoc comparisons. For unequal variances, we used Games-Howell comparisons test to

examine which message treatments were most likely to increase respondents Clean, Drain, Dry

behavior. While the F-value approached statistical significance (F=1.60 (df=19, 3,880), p=.049, η

2

=.008),

based on our post hoc message comparisons coupled with a very weak effect, we observed no

statistically significant variation.

Of the messages that received strongest agreement (M>3.40) in terms of their perceived effectiveness,

however, their message content addressed (Table 20):

a. Science-based metaphor (#15; M=3.43) - “PREVENT THE SPREAD OF AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES.

Aquatic invasive species are present in our state’s lakes and rivers and can severely impact these

ecosystems”;

b. Ecological gain (#9; M=3.41) – “PROTECT YOUR WATERS. CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY. Our aquatic

ecosystems will benefit tremendously”;

c. Protective/nurturing metaphor (#16; M=3.41) – “HELP PROTECT OUR WATERS. Aquatic invasive

species harm our lakes and rivers”;

d. Economic loss (#10; M=3.40) – “PROTECT YOUR WATERS. CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY. It will cost our

state (YOU) $ millions”;

e. I

njunctive norm (#13; M=3.40) – “PROTECT YOUR WATERS. the state’s boaters EXPECT you to

CLEAN, DRAIN, DRY your boat”;

f. Nativist metaphor (#17; M=3.40) – “NOT NATIVE, NOT WELCOME. Keep aquatic invasive species

out of our state’s lakes and rivers”; and

g. Militaristic metaphor (#18; M=3.40) – “STOP THE INVASION OF AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES.

Help fight the battle against aquatic invasive species”.

26

Table 20. Message Effect on Clean Drain Dry

1=Not at all effective through 5=Extremely effective

In your opinion, how effective would this message be at increasing boaters’

Clean, Drain, Dry behaviors?

n

M

SD

Message

1

195

3.28

.85

2

207

3.35

.75

3

198

3.32

.72

4

190

3.19

.79

5

199

3.26

.73

6

191

3.23

.78

7

195

3.32

.81

8

211

3.30

.80

9

205

3.41

.78

10

196

3.40

.81

11

139

3.29

.66

12

179

3.32

.87

13

181

3.40

.79

14

194

3.23

.78

15

199

3.43

.76

16

217

3.41

.81

17

194

3.40

.78

18

203

3.40

.79

19

200

3.37

.82

20

207

3.34

.71

Total

3900

3.33

3900

27

5.7 Message Experiment – Perceived Severity of Aquatic Invasive Species

Following the presentation of the treatment message, respondents were also asked to indicate the extent

to which they considered AIS to be a problem in their state. We conducted a chi-square test to examine

the distribution of responses across each of the treatment messages. The findings presented in Table 21

illustrate proportionate distribution across the response categories (i.e., extent of problem) for each of

the treatment messages. Response distributions were highly skewed; for all treatment messages, no less

than 80% of respondents acknowledged that AIS is “a problem” or “a major problem” within their state.

Table 21. Perceived Problem of AIS in State

Message

Treatment

Not sure

Not a

problem

A slight

problem

A problem

A major

problem

Total

0

1

2

3

4

n

%

n

%

n

%

n

%

n

%

n

%

1

8

4.1

3

1.5

25

12.8

80

41.0

79

40.5

195

100.0

2

5

2.4

2

1.0

22

11.3

94

45.4

84

40.6

207

100.0

3

7

3.5

2

1.0

18

9.2

101

51.0

70

35.4

198

100.0

4

6

3.2

3

1.6

12

6.2

90

47.4

79

41.6

190

100.0

5

6

3.0

1

.5

20

10.3

93

46.7

79

39.7

199

100.0

6

4

2.1

2

1.0

23

11.8

93

48.7

69

36.1

191

100.0

7

5

2.6

1

.5

14

7.2

95

48.7

80

41.0

195

100.0

8

6

2.8

0

.0

29

14.9

92

43.6

84

39.8

211

100.0

9

7

3.4

2

1.0

21

10.8

88

42.9

87

42.4

205

100.0

10

5

2.6

1

0.5

18

9.2

83

42.3

89

45.4

196

100.0

11

7

5.0

1

0.7

13

6.7

72

51.8

46

33.1

139

100.0

12

5

2.8

1

.6

16

8.2

94

52.5

63

35.2

179

100.0

13

5

2.8

2

1.1

19

9.7

84

46.4

71

39.2

181

100.0

14

2

1.0

2

1.0

23

11.8

100

51.5

67

34.5

194

100.0

15

7

3.5

0

.0

18

9.2

92

46.2

82

41.2

199

100.0

16

10

4.6

3

1.4

18

9.2

100

46.1

86

39.6

217

100.0

17

8

4.1

3

1.5

25

12.8

81

41.8

77

39.7

194

100.0

18

6

3.0

1

.5

19

9.7

91

44.8

86

42.4

203

100.0

19

5

2.5

0

.0

19

9.7

91

45.5

85

42.5

200

100.0

20

8

3.9

1

.5

16

8.2

109

52.7

73

35.3

207

100.0

Pearson Chi-Square (df)=55.85 (76), p=.960, Cramer’s V (ϕc)=.060

28

5.8 Message Experiment – Message Influence on Clean, Drain, Dry

Respondents were asked to indicate the likelihood that they would conduct the Clean, Drain, Dry

behaviors listed in Table 22. Based on the means reported in Table 24 and ANOVA reported in Table 23,

all messages were equally effective at encouraging Clean, Drain, Dry behavior. We observed no

statistically significant variation in the effectiveness of one message type over another. All messages

were equally effective at encouraging respondents to; a) clean mud, plants, and animals from their

boats and equipment, b) wash their boats and equipment with a pressure washer or hot water, c) drain

all water from their livewells, bilges, motors, and other receptacles, and d) dry their boat and equipment

for at least a week.

Across the behaviors, however, respondents appear to be more inclined to clean mud, plants and

animals from their boats and drain livewells, bilges, and motors rather than washing their boats and

equipment with pressure washers or hot water and drying their boats for a week before entering

another water body. The means for the former two behaviors hovered around 4.5 which approaches

“very likely” to engage whereas the means for the latter two behaviors hovered at or slightly below 4.0

indicating “likely”. Coupled with the findings presented in Tables 28, 32 and 33, respondents did indicate

that these latter two actions were more challenging.

29

Table 22. Message Influence on Clean, Drain, Dry Behavior

1=Not at all effective through 5=Extremely effective.

Based on the message you have just read, if you saw this message, how likely would you do the following

Clean, Drain, Dry behaviors the next time you go boating? (before launching in another waterbody)

Message

Clean mud, plants,

and animals from boat

and equipment

Wash boat and

equipment with pressure

washer or hot water

Drain all water from

livewells, bilges, motors,

and other receptacles

Dry boat and

equipment for

at least a week

1

M

4.30

3.70

4.35

3.95

SD

1.05

1.36

1.12

1.33

2

M

4.38

3.82

4.44

4.02

SD

.99

1.27

1.00

1.18

3

M

4.41

3.71

4.46

3.98

SD

.96

1.32

.95

1.23

4

M

4.37

3.64

4.44

4.01

SD

1.08

1.36

1.04

1.30

5

M

4.32

3.84

4.41

3.98

SD

1.05

1.25

1.10

1.24

6

M

4.27

3.70

4.38

3.92

SD

1.08

1.28

1.13

1.29

7

M

4.38

3.98

4.39

3.96

SD

1.02

1.22

1.01

1.24

8

M

4.32

3.81

4.33

3.86

SD

1.13

1.33

1.14

1.33

9

M

4.45

3.88

4.47

4.20

SD

1.02

1.33

1.04

1.14

10

M

4.37

3.96

4.49

4.15

SD

.94

1.25

.94

1.13

11

M

4.22

3.84

4.25

3.98

SD

1.22

1.27

1.26

1.23

12

M

4.39

3.56

4.47

4.06

SD

1.00

1.37

.96

1.21

13

M

4.34

3.72

4.48

4.05

SD

1.12

1.40

1.03

1.29

30

Table 23. Statistical Variation Among Message Treatments

Table 22 (continued). Message Influence on Clean, Drain, Dry

Message

Clean mud, plants,

and animals from boat

and equipment

Wash boat and

equipment with pressure

washer or hot water

Drain all water from

livewells, bilges, motors,

and other receptacles

Dry boat and

equipment

for at least a

week

14

M

4.36 3.69 4.43 3.94