Marquette University Marquette University

e-Publications@Marquette e-Publications@Marquette

Management Faculty Research and

Publications

Management, Department of

2008

The “Name Game”: Affective and Hiring Reactions to First Names The “Name Game”: Affective and Hiring Reactions to First Names

John Cotton

Marquette University

Bonnie S. O'Neill

Marquette University

Andrea Gri<n

Marquette University

Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/mgmt_fac

Part of the Business Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Cotton, John; O'Neill, Bonnie S.; and Gri<n, Andrea, "The “Name Game”: Affective and Hiring Reactions to

First Names" (2008).

Management Faculty Research and Publications

. 3.

https://epublications.marquette.edu/mgmt_fac/3

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

1

The “Name Game”: Affective and

Hiring Reactions to First Names

John L. Cotton

Department of Management, Marquette University

Milwaukee, WI

Bonnie S. O’Neill

Department of Management, Marquette University

Milwaukee, WI

Andrea Griffin

Department of Management, Marquette University

Milwaukee, WI

Abstract:

Purpose: The paper seeks to examine how the uniqueness and ethnicity of

first names influence affective reactions to those names and their potential for

hire.

Design/methodology/approach: In study 1, respondents evaluated 48

names in terms of uniqueness and likeability, allowing us to select names

viewed consistently as Common, Russian, African‐American, and Unusual. In

Study 2 respondents assessed the uniqueness and likeability of the names,

and whether they would hire someone with the name.

Findings: Results indicated that Common names were seen as least unique,

best liked, and most likely to be hired. Unusual names were seen as most

unique, least liked, and least likely to be hired. Russian and African‐American

names were intermediate in terms of uniqueness, likeability and being hired,

significantly different from Common and Unique names, but not significantly

different from each other.

Research limitations/implications: The name an individual carries has a

significant impact on how he or she is viewed, and conceivably, whether or

not the individual is hired for a job.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

2

Practical implications: Human resource professionals need to be aware that

there seems to be a clear bias in how people perceive names. When resumés

are screened for hiring, names should be left off. Our findings also suggest

that when selecting, parents may want to reconsider choosing something

distinctive.

Originality/value: This study offers original findings in regards to names,

combining diverse research from social psychology and labor economics, and

offering practical implications.

Keywords: Recruitment, Affective psychology, Ethnic groups, Discrimination

Despite laws (e.g. the 1964 Civil Rights Act) and a growing

social/cultural inclination towards fairness, discrimination in hiring

continues (Darity and Mason, 1998). For example, a recent study

found that a Caucasian applicant with a conviction for selling drugs

was more likely to be called back after a job interview than an African‐

American with no record (Pager, 2003). Like most research on hiring

discrimination, that study examined the interview process, where

interviewers are obviously aware of the race or possible ethnic origin

of the applicant (e.g. Sacco et al., 2003). However, most applicants for

a job do not make it to an interview. They are excluded through

information found in a cover letter, an application or a resumé. It is

possible for cover letters and such to influence recruiters, for example,

through ingratiation (Varma et al., 2006). However, if race or ethnic

origin is not specified, it is assumed that this process is race‐neutral.

Yet, there can be many clues signaling race or ethnicity, one of the

primary ones being the applicant's name. Some names imply that the

individual is African‐American (Jamal and Lakisha), while others sound

Caucasian (Greg and Emily) (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2003). How

are these names perceived by people who make hiring decisions? This

is the focus of our research.

Literature review

Extensive research in social psychology has demonstrated that

when we perceive others as being similar to ourselves, we are

attracted to them (Byrne, 1969). Much of this research has

concentrated on how similar attitudes lead to greater attraction, and

dissimilar attitudes lead to less attraction. We tend to like that which is

familiar and similar to us. Additional research has shown that we are

also attracted to people with similar values (Turban and Jones, 1988),

personalities (DiMarco, 1974), and demographic backgrounds (Glaman

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

3

et al., 1996). This research has examined similarity in work groups,

between superiors and subordinates, and between interviewers and

applicants. However, as we noted above, perceptions of similarity or

dissimilarity can be made before meeting a person, perhaps based on

a person's name. A common or familiar first name will be perceived as

similar, while an unusual name will appear dissimilar. How does the

uniqueness of various types of first names influence affective reactions

to those names?

Our research integrates earlier research from two academic

areas that have examined first names. First, there is considerable

research in social psychology on how an individual's name elicits

impressions about the individual, even prior to interaction. Mehrabian

(1990, 2001) and others in social psychology have examined how a

variety of factors influence the perceptions of people with certain

names. Studies have found, for example, that unique names (unusual

names or unusual spellings) connote less attractive characteristics

than names that are more common (Mehrabian, 2001), and were seen

as less desirable (Busse and Seraydarian, 1978; Mehrabian, 1992).

Most of these studies examine people's evaluative reactions to people

with these names, asking respondents to evaluate across various

dimensions (e.g. ethical, successful, fun, masculinity). Only one study

examined decisions made about people with different names. Garwood

et al. (1980) found that desirable names led to more votes in selecting

a beauty queen.

Other name attributes have also been studied. Nicknames have

been found to imply less successful characteristics (Mehrabian and

Piercy, 1993a). With male names, longer names connoted more ethical

caring, and more success (Mehrabian and Piercy, 1993b). Leirer et al.

(1982) found that formal versions of a name (e.g. Robert versus Bob

or Bobby) elicit different inferences concerning personality. Joubert

(1994) found that rare names were rated as lower in class status than

more common names. Dinur et al. (1996) found that Israeli student

preferences for names corresponded with their stereotypes about the

names.

In summary, first names lead to a variety of implied

characteristics. The most consistent findings were that more unique

names are seen as less desirable and tend to elicit more unfavorable

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

4

characteristics. The research did not directly examine racial and ethnic

differences, nor (with one exception) did it investigate decisions based

on the names.

The second area of research comes from labor economics, and

examines how African‐American names may influence hiring decisions

and life outcomes. Fryer and Levitt (2004) describe how the names

chosen by African‐American parents have shifted over time. Prior to

the 1970s, African‐Americans tended to choose common names for

their children. Beginning in the 1970s, however, to be distinct or

unique, African‐American parents increasingly chose African sounding

names, and this pattern continues today. The names tend to

incorporate elements of both African and American culture (Lieberson

and Mikelson, 1995)[1]. Fryer and Levitt's (2004) data indicates that

not only are these names distinctively African‐American, but that

among those born in the last two decades, “a distinctly Black name is

now a much stronger predictor of socioeconomic status” (p. 801). This

study found that African‐sounding names tend to be more common

among lower‐class African‐Americans. So names can imply not only

race, but also economic class. However, in looking at life outcomes,

Fryer and Levitt (2004) found that distinctly African‐American names

are unrelated to the life outcomes, after including controls for

education, education of parents, age of mother, marital status of

mother, and other factors. They suggest, however, that names may be

correlated with other determinants of productivity that are not

typically captured by the information provided in a resumé.

Employing an experimental design, Bertrand and Mullainathan

(2003) examined how names influence callbacks for job interviews.

These authors sent out resumés with a variety of African‐American and

Caucasian‐sounding names. Their results indicated that resumés with

African‐sounding names received fewer callbacks than the Caucasian

names. In addition, a higher‐quality resumé elicited more callbacks

with Caucasian names, but the greater quality had no impact on

callbacks when paired with an African‐American name. This research

was repeated and publicized in a 20/20 segment on ABC, where they

posted 22 pairs of names with identical resumés on prominent job

websites and found that Caucasian names received more attention

than African‐American sounding names (Ruppel, 2004).

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

5

Related to the research in labor economics, Bart et al. (1997)

examined how the gender and race of respondents can influence

reactions to different names on resumés. Employing a sample of

college undergraduates, they asked respondents to read a resumé with

either a Caucasian‐sounding female name (Mary Ann Roberts) or an

African‐American female name (Lakesia Washington). Consistent with

the similarity‐attraction literature (Byrne, 1969; Goldberg, 2005), the

authors found that female raters evaluated the female candidates

higher than male raters, and that African‐American raters evaluated

the African‐American candidates higher than the Caucasian raters

(Bart et al., 1997, p. 302). In addition, female raters had lower pay

expectations than male raters, and African‐American female raters had

the lowest pay expectations of all.

The research above has answered a number of interesting

questions. However, there are still major concerns and gaps in current

knowledge in this area. The research from social psychology has

examined a variety of name characteristics, but the dependent

variables are often global assessments on general dimensions (good‐

bad, active‐passive, strong‐weak, successfulness, ethical, etc.). It is

difficult to say how these characteristics influence actual behavior, for

example, hiring decisions. In addition, this research has not compared

racial and ethnic names. Bertrand and Mullainathan's (2003) study

from labor economics examined job‐hiring behavior, but it was not

clear whether the effects were entirely due to race. For example, some

of the Caucasian names used were Emily, Allison, Kristen, Brendan,

Geoffrey, and Brett. Many of these names are not only Caucasian, they

also tend to be perceived as above average in success (Mehrabian,

1990). It is possible that the names employed varied not just on race,

but also on perceptions of familiarity, socioeconomic status, or other

characteristics (Fryer and Levitt, 2004). For example, the African‐

American names (Latoya, Ebony, and Tremayne) are more unique

than the Caucasian names (Jill, Anne, Greg). In addition to race, a lack

of familiarity towards certain names may influence reactions. These

additional explanations for the effects attributed to race may also

apply to the findings of Bart et al. (1997).

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

6

Research issues

Although prior research hints at the impact that the uniqueness

of African‐American names can have on various outcomes, no research

to date has examined the influence of uniqueness on individuals'

perceptions of African‐American and other ethnic names and their

potential for hire. In this paper we expand on prior work by examining

whether individuals with unique or ethnic names are perceived the

same way as those with African‐American names.

Based on the research reviewed above, we argue that as names

vary in how unique they are perceived, so will they vary in how well

they are liked. Therefore we make the following hypotheses:

H1. Common names will be seen as familiar by individuals, and

more unique names will be seen as less familiar.

H2. Common names will be liked the most and names which are

the most unique will be liked the least.

H3. African‐American and other ethnic names will be seen as

more unique than common names, and will therefore be liked

less than common names.

Two studies were conducted to test the hypotheses above. The

first study examined responses to a wide variety of names in order to

determine if individuals perceived differences in uniqueness between

the names and if uniqueness was related to likeability. The second

study was designed to focus more closely on a selected subset of

names. In addition to examining the uniqueness of names on

likeability, the second study also examined how uniqueness influenced

hiring intentions.

Study 1

Sample and procedure

In the first study we examined the perceptions of working adults

and undergraduate business students to various names. Similar to

past research, we prepared collections of Common names (i.e.

categorized as White names in prior studies) and African‐American

names. We expanded our name categories to include Russian names,

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

7

which would be racially classified as White, but like the African‐

American names would be perceived as more unique (and less similar)

than the Common names. In this way we could differentiate between

race and uniqueness in our comparisons across name categories. We

also included a group of unique names, which we labeled Unusual. For

Common names, we accessed the Social Security Administration

website (www.ssa.gov/OACT/babynames/), which identified the most

common male and female baby names in the USA for the past three

decades. We selected male and female names that consistently ranked

as the most popular names, as these names would be most likely to be

perceived as similar by respondents[2].

Since the SSA website did not provide a list of names by race or

ethnicity, we conducted an internet search on a variety of websites

that provided names for each of the remaining categories. African‐

American and Russian names were chosen based on those names we

found most often and we also included several names examined in

prior studies. Unusual names were chosen based on those names

thought by the researchers to be fictitious and/or unheard of in

mainstream American culture (i.e. not used by any popular/media

person).

A total of 48 names (six male and six female from each of the

four categories) were employed in this study. These names were given

to 505 individuals enrolled in business programs at a university located

in the upper Midwest. Of these individuals, 153 were working adults

(employed full‐time and participating in a part‐time graduate business

program) and 352 were full‐time undergraduate business students

(either not working or working part‐time). Fifty‐five percent of the

sample was male and 45 percent was female. In terms of

demographics, 81 percent of the sample were Caucasian, 4 percent

were African‐American, 4 percent were Hispanic, and 6 percent

identified themselves as Asian. Students did not receive extra credit

for participation, but were simply asked to volunteer their time. The

vast majority of students (approximately 95 percent) responded. To

avoid exhaustion (and incomplete responses), half of the names were

given to about half the respondents, and the other half of the names

were given to the rest of the respondents. Using a Likert scale ranging

from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), the respondents were

asked to evaluate names across a variety of dimensions, including

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

8

uniqueness, likeability, nationality, ethnicity, and gender. All questions

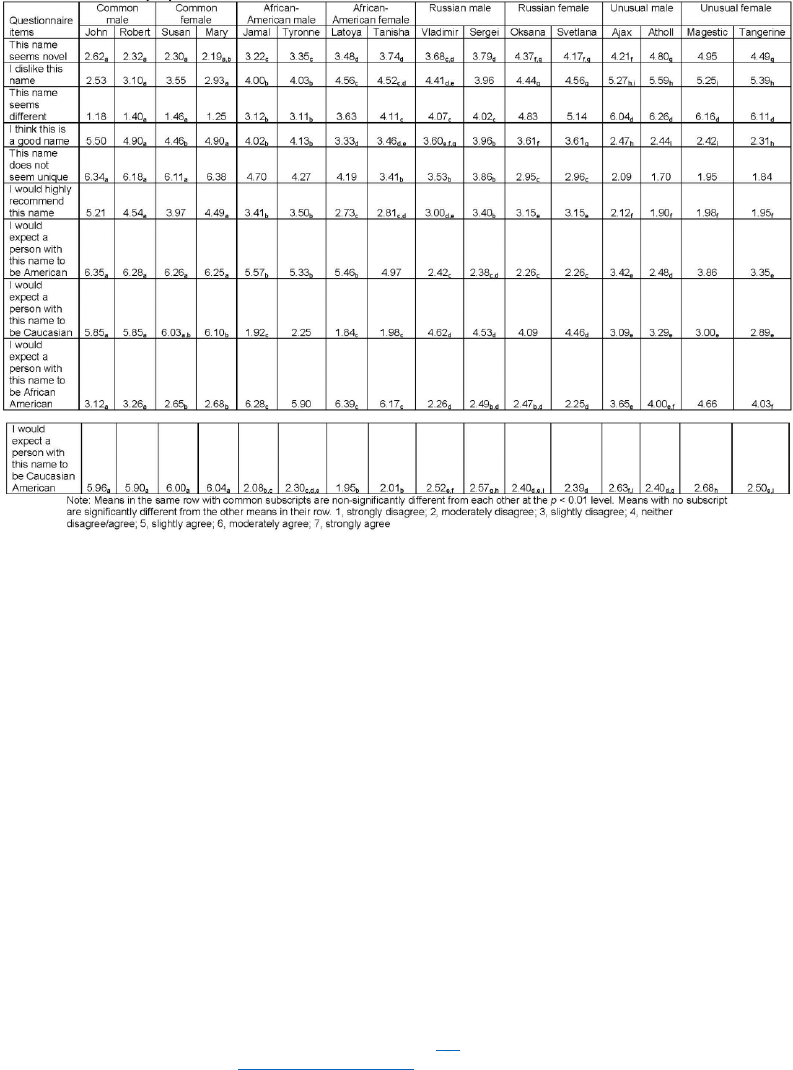

used are listed in Table I.

Results

One purpose of Study 1 was to select names that are

consistently viewed as Common, African‐American, Russian, and

Unusual. On a scale from 1 to 7, the following names were rated at 1.5

or below as being “different”: John, Robert, Mary, and Susan. The

following names were rated at or above 6.0 as expected to be African‐

American: Tyronne, Jamal, Latoya, and Tanisha. The following names

were rated below 3.0 as expected to be American (i.e. were not seen

as American): Vladamir, Sergei, Oksana, Svetlana. Finally, the

following names were rated at or above 6.0 as being “different”: Ajax,

Atholl, Magestic, and Tangerine. In addition to confirming our

expectations regarding perceived nationality and ethnicity, the

respondents viewed the names as being male or female, although

these findings were not as consistent for the Unusual names as they

were for the other categories.

A second purpose of Study 1 was to see how the various names

were viewed in terms of how unique and how likeable they were

perceived to be. We attempted to combine several of the questionnaire

items into scales; however, the reliabilities were so low that we had to

examine the questions individually. When comparing the 16 names

chosen above, we found a consistent, often statistically significant

pattern, although this was not true for every question with every

name. Table I shows the means for all of the questions across the 16

names selected.

As expected, Common names were seen as less “different” than

other names, followed by the African‐American names and Russian

names, followed (distantly) by the Unusual names. These effects also

carried over to the likeability of the names. Common names were seen

as being more likeable or better than the other three groups. Unusual

names were seen as being less likeable or not as good as the other

three groups. African‐American names and Russian names were in the

middle, usually significantly different from Common and Unusual

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

9

names, but often not different from each other. Similar results were

found for both male and female names.

The means in Table I suggest that uniqueness in names has a

powerful impact on likeability concerning those names. Race and

ethnic origin seem to also have an impact, but it is not clear if these

are due to perceptions of race/ethnicity, or whether the novelty of

these names makes them less likeable. To explore the possible

influence of race and ethnic origin on individuals' perceptions of liking,

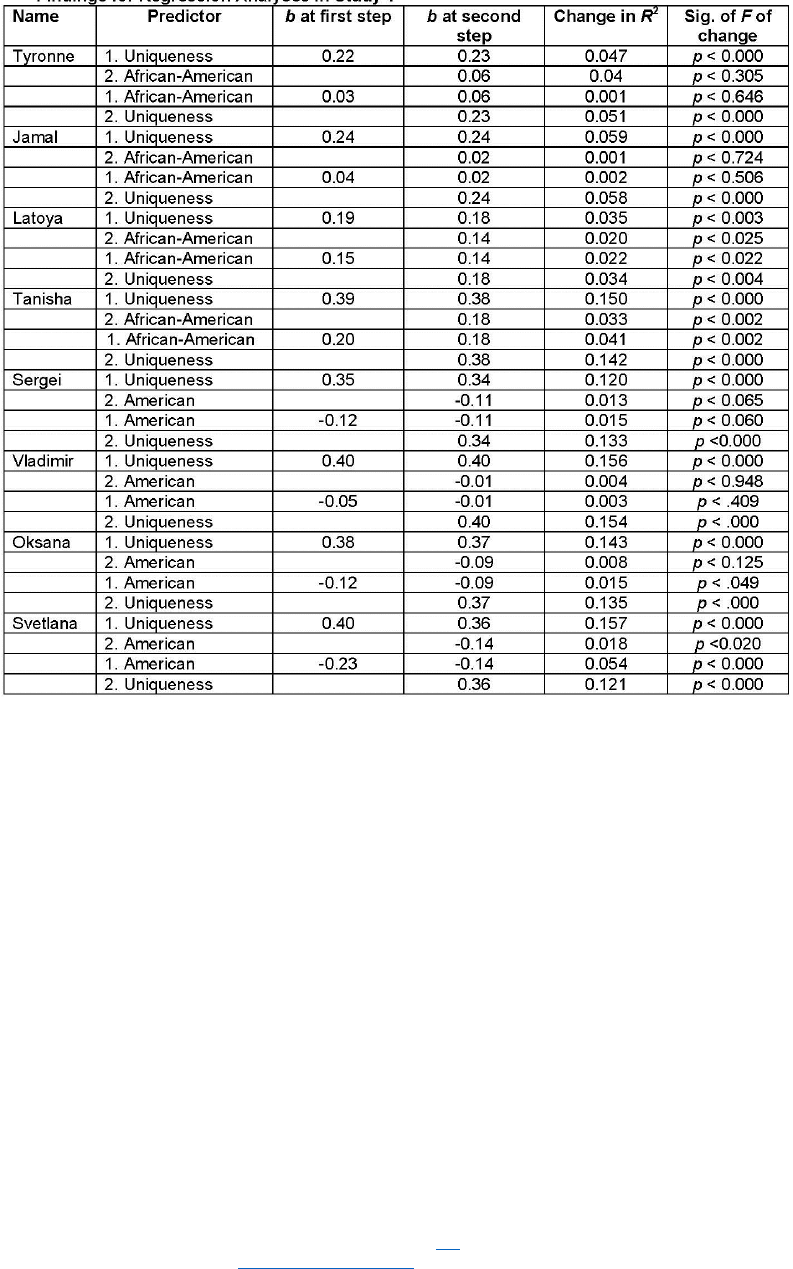

post hoc regression analyses were conducted on each of the four

chosen African‐American names (Jamal, Tyronne, Latoya, and Tanisha)

and the four chosen Russian names (Oksana, Svetlana, Vladimir, and

Sergei).

The regressions on African‐American names employed both

uniqueness (“This name seems different”) and perceptions of being

African‐American (“I would expect a person with this name to be an

African American”) as predictors of liking. Two hierarchical regressions

were performed for each name. One regression entered uniqueness

and then being African‐American into the equation; the second

regression entered being African‐American and then entered

uniqueness in the second step. The analyses for the male names found

that perceptions of being unique significantly predicted liking, but

expectations of the person being an African‐American had no effect

(see Table II). This pattern was consistent for both male names,

across all respondents (both working adults and undergraduate

students). The pattern was somewhat different for the female names.

For these names, both the perceptions of being unique and the

expectation of being an African‐American were related to liking. These

results were found for both of the female names, across all

respondents. However, in looking at the change in R

2

, it is clear that

even when both are significant, being unique is a stronger predictor

(average R

2

=0.090) than being African‐American (average R

2

=0.029).

The hierarchical regression analyses above were also performed for

the African‐American names that were not chosen for Study 2, with the

same results.

The regressions on Russian names employed both uniqueness

(This name seems different”) and perceptions of being American (“I

would expect a person with this name to be an American”) as

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

10

predictors of liking. Two hierarchical regressions were performed for

each name. One regression entered uniqueness and then being

American into the equation; the second regression entered being

American and then entered uniqueness in the second step. The

analyses found that both uniqueness and being an American predicted

liking for one of the four names (Svetlana). For the other three names,

being American was not a significant predictor. Overall, the effect for

uniqueness was very powerful (average change in R

2

=0.15) while the

effect for not being American, even when significant, was much

smaller (average change in R

2

=0.014).

Discussion

The findings above suggest that uniqueness in names can have

a powerful impact on likeability concerning those names. H1 and H2

were clearly supported. H3 was partially supported, in that race and

ethnic origin at times also had an impact. However, these factors

appear to be less powerful than uniqueness, disappearing entirely for

some of the names when controlling for uniqueness.

Although this study examined our hypotheses, there are several

limitations. First, a single survey was used to select names based on

perceptions of race and ethnicity. Then, within the same survey,

respondents evaluated the names in terms of liking. To avoid the

problem of common methods bias, it would be more effective to have

one sample determine the choice of names and a second sample

evaluate the names. Second, not all respondents responded to the

same set of names. However, having all individuals respond to all

names would have been an exhaustive process and we expected that

respondents would have been incapable of accurately completing such

a lengthy survey. We made every attempt to distribute the names

evenly (e.g. equal distributions of Common, Russian, African‐

American, and Unusual names) across the two surveys and two

samples. However, it is possible that the effects noted in our results

may be influenced by comparisons with the other names the

respondents read and evaluated on their particular survey and may

not generalize to other names or respondents. Third, evaluations of

uniqueness and liking were assessed with single items. We had

intended to combine the various questions into scales, but did not find

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

11

sufficient consistency between the items to develop valid scales.

Finally, we did not assess intended behavior, such as whether a

respondent would want to hire someone with that name. In the next

study, we conduct a replication of Study 1 and extend our analyses to

examine respondents' intentions to hire individuals with these names.

In this study we also controlled for some of the limitations noted in

Study 1, where possible.

Study 2

Sample and procedure

This study utilized the 16 names identified in Study 1 as best

fitting the ethnic, racial and common/unique categories we

established. In order to conduct a replication of our first study, we

asked respondents to evaluate the names in terms of how unique they

were and how much they liked the names. Then, to capture

perceptions related to employment behavior, we asked respondents

several questions related to how willing they would be to hire people

with those names. The respondents were 166 students in a variety of

part‐time graduate business programs in a university located in the

Midwest. The survey asked whether respondents had participated in

the first study, and 4.2 percent (or seven of the respondents) said

they had. This low number of overlapping respondents indicates that

our sample was largely a new sample of working adults. This provided

an opportunity to conduct a replication of perceptions of uniqueness

and liking from Study 1. The mean age among these respondents was

30 years, and they averaged 8.41 years of work experience, providing

a sample that is likely to be representative of working adults in

positions with hiring responsibilities. Of the respondents, 61 percent

were male and 39 percent were female. In terms of race, 78 percent

were Caucasian, while 4 percent were African‐American, 12 percent

were Asian or Pacific Islander, 2 percent were Hispanic, and 3 percent

were “other”. All respondents rated all of the names. Using the results

from the first study, we employed the 16 names that respondents

reliably identified as Common, African‐American, Russian, and

Unusual. Half of the names were female, the other half male. We

therefore have two names for each cell in an eight‐cell format.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

12

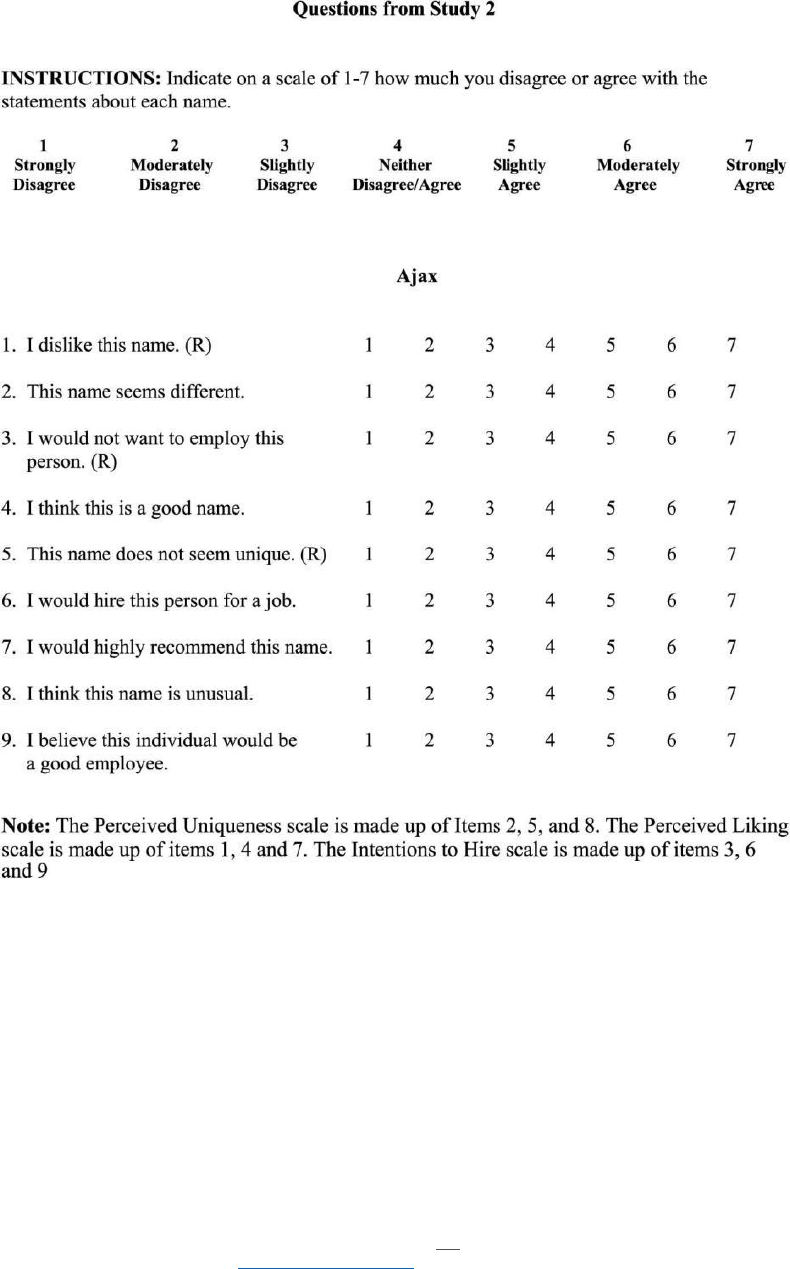

Measures

The three primary dependent variables were likeability,

uniqueness, and hiring intentions related to the name. Three questions

were employed to measure each variable (see Appendix). The

reliabilities of these scales were assessed for each name. These

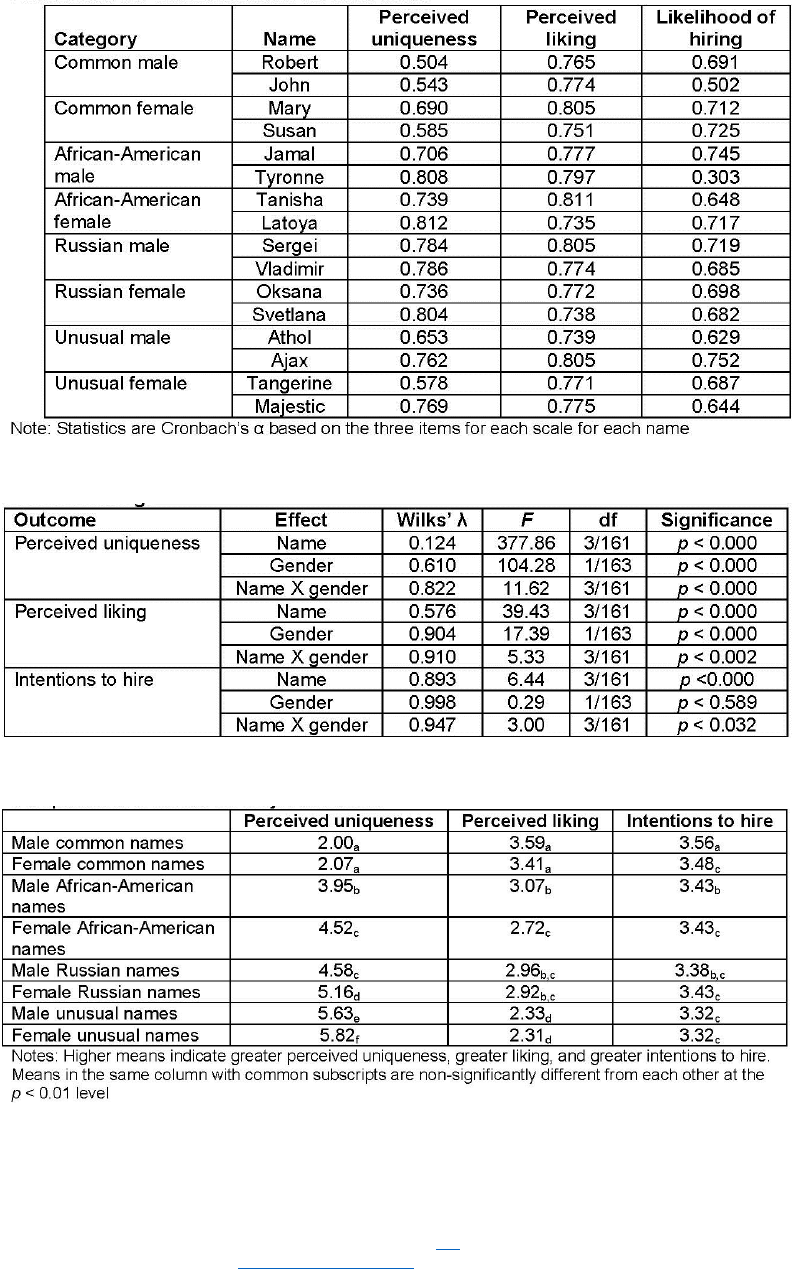

reliabilities are presented in Table III.

The reliabilities for the uniqueness scale ranged from 0.50 to

0.81, with the majority between 0.74 and 0.81. For perceived

likeability the reliabilities ranged from 0.74 to 0.81, with the majority

between 0.77 and 0.81. For intentions to hire, the reliabilities ranged

from 0.30 to 0.75, with the majority between 0.69 and 0.75. There

were no detectable patterns between the names with low reliabilities.

Results

The structure of the study can be considered a 4×2 factorial

design, with four levels of name type by gender. The levels of name

type range in sequence from Common names to African‐American, to

Russian, to Unusual names. This approach represents the order of

perceived uniqueness of the names in Study 1. As expected, the

overall analyses indicate that the type of name influenced perceptions

of uniqueness, likeability, and intentions to hire. However, the more

interesting findings are the direct comparisons among the types of

names. Therefore, for each of the dependent measures we performed

an overall MANOVA followed by comparisons across the various types

of names. The overall analyses are 4×2 repeated‐measures MANOVAs

(since all respondents evaluated all of the names). The follow‐up

comparisons are a priorit‐tests, with expected differences between the

four types of names. Because of the large number of t‐tests, we are

employing a significance level of p<0.01.

In terms of perceived uniqueness, the overall MANOVA was

significant for name type (Wilks' λ=0.124, F=377.86, p<0.001), for

gender (Wilks' λ=0.963, F=104.28, p<0.001), and for the name

category by gender interaction (Wilks' λ=822, F=11.62, p<0.01)[3].

The findings for the MANOVAs are presented in Table IV.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

13

Because of the gender interaction, separate a priori t‐tests were

conducted for all categories of male and female names. These t‐tests

indicated that perceptions of uniqueness were significantly different

across all name types for the male names (p<0.001), with the

Common names seen as least unique, followed by the African‐

American names, followed by the Russian names, with the Unusual

names perceived as being the most unique. The results were similar

for female names. The only exception to this pattern was that female

African‐American names were not seen as significantly different from

male Russian names. The findings for the t‐tests are presented in

Table V.

The MANOVA for the likeability scale was also significant for

name type (Wilks' λ=0.576, F=39.43, p<0.001), for gender (Wilks'

λ=0.904, F=17.39, p<0.001), and for the name category by gender

interaction (Wilks' λ=0.910, F=5.33, p<0.002). Again, separate t‐tests

were conducted for male and female names. The t‐tests for the male

names indicated that all of the name types were significantly different

from each other (p<0.001) in terms of likeability, with the exception of

the African‐American names and the Russian names. As in Study 1,

the Common names were liked the most, followed by the African‐

American names, followed by the Russian names, with the Unusual

names being the least popular. However, the difference between the

African‐American and Russian names was non‐significant (p<0.11). A

similar pattern was found for the female names. With female names,

the Common names were liked the most, followed by the Russian

names, the African‐American names, and the Unusual names. Like the

male names, the African‐American female names were not significantly

different from the Russian names.

In terms of intentions to hire individuals with the name, the

MANOVA was significant for name type (Wilks' λ=0.893, F=6.44,

p<0.001), but not for gender (Wilks' λ=0.998, F=0.293, p<0.60), and

was marginally significant for the name by gender interaction (Wilks'

λ=0.947, F=3.00, p<0.05). As predicted, respondents were most

likely to hire someone with a Common name, followed someone with

an African‐American name, a Russian name, and least likely to hire

someone with an Unusual name. Differences between the Common

male names and the other male names were significant (p<0.001).

The Unusual names were significantly different from the Common

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

14

names and the African‐American names, but not the Russian names

(p<0.02). The African‐American and Russian names were non‐

significantly different from each other. With the female names, there

were no significant differences at the p<0.001 level. However, if a less

conservative significance level was used (e.g. p<0.02), the Unusual

names would have been significantly different from the other three

groups. The Common, African‐American, and Russian names were non‐

significantly different from each other.

We also conducted additional MANOVA analyses to see if

characteristics of the respondents influenced their reactions to names.

No significant effects or interactions were found for the gender of the

respondents. In terms of race, Caucasian respondents (n=131) were

compared with all other groups (n=34)[4]. This analysis also found no

effects. Finally, the respondents were divided into three groups on the

basis of work experience. These groups consisted of those respondents

with zero to four years of experience (n=56), five to ten years of

experience (n=55), and those with more than ten years of experience

(n=49). Like the other respondent characteristics, no effects were

found for respondents' work experience.

Discussion

The two studies here demonstrate that “a rose by any other

name” is not appreciated the same way. Our results from both studies

indicate that the name that an individual carries has a significant

impact on how he or she is viewed, and conceivably, whether or not

the individual is hired for a job. Names that were seen as being more

unique were liked less, and in the second study, were less likely to be

hired. The best names (most liked and rated most likely to be hired)

were the most common ones (e.g. Mary, Robert), while the worst

names (least liked and least likely to be hired) were the most unusual

(e.g. Atholl, Magestic). In between these extremes were African‐

American and Russian names. These names were seen as being

intermediate in terms of being unique, and were also intermediate in

terms of how much they were liked and how likely they were to be

hired.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

15

In spite of the effects above, Study 2 simply asked respondents

how likely they would hire a person with a specific name. It is a

considerable leap from there to conclude that this would actually lead

to differential hiring behavior. Therefore, our next step was to examine

this hiring behavior in a controlled, laboratory setting. In Study 3,

described below, respondents were given resumés containing the

various names, and then asked how likely they would be to hire this

person.

Study 3

Sample

The respondents for this study were 105 working adults enrolled

in a part‐time MBA program who had not participated in either of the

earlier studies. The students varied in age from 21 to 47, with a mode

of 26 and a mean of 28. They averaged 6.25 years of work experience,

and 55 percent reported that they had been involved in hiring at some

point. Of the sample, 62 percent were male and 31 percent were

female, with 7 percent not reporting gender. In addition, 82 percent

were Caucasian, with 2 percent African‐American, 4 percent Asian or

Pacific Islander, 3 percent Hispanic, and 2 percent “other”. A total of 7

percent of the sample did not indicate their race.

Procedure

The students were asked at the beginning of a class if they were

willing to participate in a study examining hiring decisions. Students

did not receive extra credit for participation, but were simply asked to

volunteer their time. Virtually all (more than 95 percent) students

participated. Respondents were told that they should imagine

themselves hiring a new administrative assistant for PMA Consultants

LLC, an actual company located in Chicago. The instructions included

an actual ad for an administrative assistant taken from the Chicago

Tribune. Respondents were given a booklet with eight resumés and

eight sets of questions regarding hiring. Each of the resumés was

constructed to provide a reasonable candidate for the position.

Pretesting of the resumés had been conducted with graduate students

enrolled in a staffing class in order to assess comparability of the

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

16

resumés in terms of education and experience. Slight modifications

were made to certain resumés, as recommended. The resumés used

the same names employed in Study 2, with one male and female

name from each of the four name categories. The names, resumés and

their order were randomly assigned to each booklet. After each

resumé, six questions were listed for respondents to evaluate on a

seven‐point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 7=strongly agree)

how likely they would be to hire the candidate (e.g. “Given what I

know, I would hire this person for the position”). At the end of the

booklet were several demographic questions.

Results

Reliability analyses demonstrated that the six evaluation

questions were highly interrelated. The reliability of the scales

(Cronbach's α) varied from a low of 0.914 (White female resumés) to a

high of 0.938 (unusual female resumé). Like Study 2, the responses

were examined in an overall MANOVA followed by comparisons across

the various types of names. The overall analyses are 4×2 (name

category by gender) repeated‐measures MANOVAs and the follow‐up

comparisons are a priorit‐tests, with expected differences between the

four types of names.

The overall MANOVA was not significant for name type (Wilks'

λ=0.944, F=1.998, p<0.12), for gender (Wilks' λ=0.995, F=0.572,

p<0.50), nor for the name category by gender interaction (Wilks'

λ=0.947, F=0.894, p<0.50). Given the lack of overall effects, it was

not surprising that none of the t‐tests were significant at the 0.01 level

(largest t=2.02). Additional analyses were performed to see if

demographic characteristics of the respondents (sex, race, work

experience, hiring experience) influenced their reactions to names.

Very few significant interactions were found for these analyses (three

of 48 effects were significant at p<0.05).

Discussion

Given the strong findings from Study 1 and Study 2, the total

lack of effects in Study 3 was surprising. There are several possible

explanations. One possibility is that names influence affective

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

17

reactions but not behavior. In other words, people may not like certain

types of names, but these feelings do not influence hiring. However,

field research from Bertrand and Mullainathan (2003) and Bart et al.

(1997) suggests that there should be effects for names that indicate

race or gender. A second possible explanation is that our hiring

simulation did not completely imitate what happens in an actual

business context. Instead of seeing the task as a part of everyday

work, the respondents may have perceived it as some type of

academic test or problem, and worked hard studying the resumés to

make their decision. Since respondents were employed full‐time, many

in managerial positions, they may have been exhibiting an acquisitive

orientation of impression management. This occurs among managers

when they are concerned about obtaining approval from their audience

(Palmer et al., 2001). In the present context, students knew that

individuals administering the survey were colleagues of their course

instructors and they may have been attempting to positively influence

their instructors' initial impressions of them. This explanation is

consistent with some of our experiences in administering the survey.

First, respondents were given the opportunity to write written

comments after evaluating each candidate. Over 76 percent of the

respondents provided open‐ended comments, and many respondents

wrote comments about every candidate. Second, it took most

respondents about 15 minutes, and some as long as 20 minutes, to

evaluate eight single‐page resumés. It is unlikely that a typical hiring

manager spends that much time and effort in a preliminary review of

resumés for non‐exempt positions. Written comments by respondents

in Study 3 suggested a strong focus on the schooling and prior work

experiences of applicants, despite it being an administrative assistant

position (i.e. the position did not require advanced education or

extensive work experience).

This brings up an interesting question: at what point in the

hiring process does an applicant's name influence the hiring manager?

When quickly sorting through a large stack of applicant resumés,

managers frequently scan for key words before reading in more depth

(Capelli, 2001). However, in our laboratory test, the respondents

carefully went through all of the information before making any

evaluations, much like managers do after completing the preliminary

screening process. This may have resulted in the names having no real

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

18

impact. In practice, however, managers first do a superficial sorting of

resumés, and first impressions may be based on similarity to oneself

early in the screening process.

In essence, it may be that our laboratory task does not reflect

the actual process managers follow when hiring. In most contemporary

workplaces, managers must balance the costs associated with

spending their valuable time against the anticipated value of a good

hire. Instead of reading every applicant's materials in depth, a hiring

manager scans the resumé for specific skills or experience, sorting the

resumés accordingly. We investigated this possibility by asking several

HR managers about the process they typically use in hiring for similar

non‐exempt positions. Without exception, every manager responded

that they always skim the resumés they are evaluating first, allocating

much more time only to a small subset of qualified applicants. As one

respondent explained, “Typically, I only look at education/degree,

company name and dates and titles”. Another respondent commented,

“I probably spend about 5 seconds per resumé in the initial skimming

process”. Another estimated that about 30 seconds was spent per

resumé. One piece of information in this brief analysis would be the

person's name, which could have a significant impact.

Sociology research examining homophily – the theory that

contact between similar people is considerably greater than with

dissimilar people – finds that individuals often negatively discriminate

when they know little about a person other than their education,

occupation or similar characteristics (see McPherson et al., 2001). In

addition, inter‐group contact theory implies that as inter‐group contact

increases (in this case, racial and ethnic inter‐group contact exposure),

inter‐group prejudice decreases (thereby reducing the likelihood of

active discrimination (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006). And, Christopher

(1998) suggests that “although a person's first name does make a

difference in how he or she is perceived by others, the impact of a

name diminishes when additional information about the person is

available” (p. 1180).

These arguments suggest that if a name were to influence a

hiring manager, it would probably occur early in the hiring process,

when little is known about the applicant beyond his or her name and

when little time is spent carefully reviewing the resumé.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

19

Overall discussion

The results from these three studies complement and expand on

the findings from research in social psychology. We have taken the

results from those studies and applied them to personnel decisions.

Our results also complement and expand on the findings from labor

economics, principally the findings from Bertrand and Mullainathan

(2003) and Bart et al. (1997). However, our findings suggest that their

results may not have been due simply to racial prejudice. We found

similar effects for both African‐American and Russian names. We found

prejudice for a variety of unique names, not just African‐American

names.

The regression analyses from Study 1 indicated that the African‐

American and Russian names were not liked as much as Common

names because they were unusual, and because of prejudice (against

African‐Americans and non‐Americans). However, the uniqueness of

the names appeared to be a stronger predictor of liking than the racial

or ethnic category.

Contrary to the findings of Bart et al. (1997), in Study 2 we

found no differences between Caucasian respondents and other groups

in how they evaluated the different names. However, there are several

differences between our sample and that of Bart et al. (1997). First,

the sample in that study was much more evenly distributed between

Caucasian and non‐Caucasian respondents than our study (54 percent

versus 78 percent Caucasian, respectively). Second, their subjects

were all college undergraduates. In Study 2, our respondents were

working adults in a part‐time MBA program, presumably possessing

more actual work experience. Finally, their sample was from the

Southeastern part of the USA, while ours was from the upper Midwest,

and regional variations in values and attitudes may exist. It is very

possible that one or more of these differences accounts for the

variation in results.

Another recent study by Smith et al. (2005) found that names

(and the gender they imply) influence the recommendations made by

HR professionals in response to information about applicants (e.g.

salary history, single or multiple employment gaps). In fact, a recent

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

20

study found that occupational stereotypes influenced perceptions of

applicant resumés such that race effects became non‐significant when

occupation was considered (King et al., 2006). Although there is a long

history of discrimination based on gender and race, our results from

Study 3 suggest that these problems may occur earlier in the hiring

process than suspected. As Smith and her colleagues suggest, whether

such discriminatory behavior is unintentional or not, the outcomes are

still devastating for successful diversity initiatives. Although many

managers dislike preferential hiring, it can be a valuable mechanism

for promoting fair representation of females and minorities in the work

place (Singer and Lange, 1994). As the ultimate gatekeepers of both

diversity and EEO/affirmative action initiatives, HR professionals need

to demonstrate how such initiatives add value to the organization

(Hammonds, 2005). Therefore, it becomes incumbent upon HR

professionals to discourage the use of stereotypes among anyone who

participates in hiring. They must continue to promote and coach

managers in the analytical techniques necessary to match qualified

applicants with available positions, especially if they want to be viewed

as key organizational players (Ulrich and Beatty, 2001).

Although previous research has indicated a prejudice against

African‐American sounding names (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2003),

our research suggests that the issue may not be simply race, but also

novelty. Individuals utilize schemas as a means for simplifying

cognition in situations where there is incomplete information (Elsbach

et al., 2005). Louis and Sutton (1991) suggest that individuals rely on

“habits of mind” in which we engage in much of our behavior without

paying attention to it (p. 55). We propose that when faced with a

name, especially an unusual name, individuals may initially respond

with some type of stereotype for the name, based on uniqueness and

other factors (e.g. race, ethnicity). The unique sound of a name to a

recruiter can set off a chain of discomfort and dislike which, although

unintentional, may result in an early dismissal from the recruitment

process and result in fewer employment opportunities for individuals

with unique names. Our results suggest that one reason African‐

American names are not liked as much as Common names is because

they are perceived as being unique. The same is true for Russian

names. Imagine the complex implications in a specific hiring situation:

a respondent will be less likely to hire Jamal versus John. However,

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

21

this may not be simply racial prejudice, as the respondent is also less

likely to hire Sergei, and much less likely to hire Atholl.

When we presented this research to a group of recruiters,

several of them lamented that their clients frequently reject potential

applicants with unique names – applicants with solid qualifications and

excellent employment histories – from initial consideration and, in

some cases, from further consideration for executive positions. One

recruiter complained that a client vehemently rejected several pleas to

consider a well‐qualified applicant stating, “I couldn't possibly work

with a person who has that name”. This recruiter's experience was

confirmed by nods of agreement from other recruiters in the room,

with most individuals expressing chagrin at the difficulty they

experienced in placing applicants with unique names. What makes this

even more disheartening is the fact that these well‐intentioned

recruiters openly acknowledge their frustration at this discriminatory

behavior, but they indirectly encourage it by sending their clients other

applicants with more common names. They rationalized this behavior

by commenting that their own livelihood (and continued employment)

depends on being able to fill orders for their clients. As a result, the

behavior continues.

We noted earlier that there is a growing tendency for African‐

Americans, especially lower‐class African‐Americans, to select unusual

names for their children in order to help them identify with their

African roots. Critical Race Theory describes examples of how people

of color make decisions to project their racial identity, for example,

with hair style (Carbado and Gulati, 2003). However, selecting an

unusual name may be detrimental to one's child in the long run. Along

with any racial discrimination that may exist, the African‐American

with an unusual sounding name like Erasto (an male East African name

meaning “man of peace”) or Adeola (a female Nigerian name meaning

“crown of honor”) may be facing two strikes when applying for a job

before he or she is even called in for an interview. Recognizing this

problem may alert individuals with unusual names to find ways of

addressing the negative perceptions that they are likely to encounter.

An example of this can be found in the story of a young actor

whose parents gave him a traditional Indian name. Kalpen Modi

experienced few auditions and a dismissive attitude among producers

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

22

when attempting to get acting jobs in the USA. He changed the name

on his resumé to a more common, American‐sounding name (Kal

Penn) and discovered that his auditions increased by almost 50

percent (Bhattacharyya, 2004). This subsequently led to appearances

on NBC's hit show, Law and Order. Born in the USA but given a

traditional Asian name, the actor found he would be more successful

by taking on a more common name. This simple example supports our

theory that novelty may have a downside.

There are, of course, limitations with this research. The most

serious limitation is that we are assessing what people say in a

laboratory situation. Although individuals may say they do not like a

particular name, or that this might influence hiring, we do not know

how much this affects actual behavior in the real world. For example,

the results from Study 3 suggest that job history, education and other

information from a resumé may overwhelm any prejudice coming from

the name. However, an unusual name might keep a resumé from

being read more closely, thereby not allowing job history, education

and other information to come forth. Organizational behavior research

has shown a strong correlation between an individual's attitudes and

subsequent behavior (Lee and Mitchell, 1994) and the study by

Bertrand and Mullainathan (2003) demonstrates such real behavior, in

accordance with our findings.

A second limitation is that we have only four names (two male

and two female) to represent each type of name in both studies.

Although we pretested these names in Study 1 for perceptions of

uniqueness, nationality and likeability, it is possible that the names we

selected are not representative of the categories to which they

correspond. Until additional names can be examined, we suggest

caution in generalizing the results beyond the present study. A third

possible limitation is that sample is from a single city in the upper

Midwest of the USA, and so may not be a typical sample of American

business people. However, our results are consistent with most prior

research conducted in other parts of the USA.

Finally, we have the issue of common method bias, the

possibility that respondents are answering questions in a consistent

fashion because they are being asked all of these questions in a single

survey. We can provide two arguments that mitigate this problem.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

23

First, we selected the names and collected data about how they were

perceived (as African‐American, as male or female, etc.) in Study 1.

We then asked questions concerning how people reacted to these

names in Study 2, with new respondents and found similar results.

Second, although the results for the various outcomes had similar

patterns, they were far from identical. The strongest results were

found in terms of perceived uniqueness, with somewhat weaker effects

in likeability, and the weakest findings in terms of whether the

respondent would hire the individual. This is precisely the pattern we

would expect if we propose that the names are perceived as being

unique, and this lack of familiarity leads to less liking, which in turn

affects decisions to hire. If the results were due to common method

bias, we would expect more identical results across all three outcomes.

In summary, there seems to be a clear bias in how people

perceive names. This suggests that human resource professionals

need to be aware of this predisposition and continually train their

hiring managers to do the same. When resumés are screened for

hiring, names (like pictures) should be left off to avoid potential

discrimination. In addition, applications and resumés that are received

could be routed to hiring managers with initials (see Smith et al.,

2005) or with applicant numbers to represent the applicant so as to

avoid any possible dislike of the name. Since applications are routinely

entered into an organization's human resources database, assigning an

applicant number in place of a name might be a worthwhile and easy

alternative to minimize potential bias. In this way, prescreening of

applicants can be conducted by key word searches, as is typically done

by sophisticated electronic recruitment software or job boards (e.g.

Monster.com) (Capelli, 2001). This can help ensure that hiring

managers focus on skills and abilities, rather than playing “the name

game”.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

24

Notes

Lieberson and Mikelson (1995, p. 929) define “unique” as “a name given to

no other child born in that year who is of the same sex or race”.

Critical Race Theory posits that race is a basic organizing principle in

American society, and that what is common and unlabeled will be

assumed to be Caucasian (McDowell and Jeris, 2004; Grimes, 2002).

Although we present Wilks' λ, the ANOVAs (via SPSS 13.0) also calculated the

values for Pillai's trace, Hotelling's trace, and Roy's largest root. Since

all of these measures gave identical results, we only present Wilks' λ.

Because of insufficient sample size, analyses were not conducted for the

individual racial/ethnic groups.

References

Bart, B.D., Hass, M.E., Philbrick, J.H., Sparks, M.R. and Williams, C. (1997),

“What's in a name?”, Women in Management Review, Vol. 12 No. 8,

pp. 299‐308.

Bertrand, M. and Mullainathan, S. (2003), “Are Emily and Greg more

employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor

market discrimination”, NBER Working Paper No. 9873, National

Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Bhattacharyya, A. (2004), “You can call him Kal”, Mantram, July, pp. 30‐5.

Busse, T.V. and Seraydarian, L. (1978), “Frequency and desirability of first

names”, Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 104 No. 1, pp. 143‐4.

Byrne, D. (1969), “Attitudes and attraction”, in Berkowitz, L. (Ed.), Advances

in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol 4, Academic Press, New York,

NY, pp. 35‐89.

Capelli, P. (2001), “Making the most of on

‐

line recruiting”, Harvard Business

Review, Vol. 79 No. 3, pp. 139‐46.

Carbado, D.W. and Gulati, M. (2003), “The law and economics of Critical Race

Theory”, The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 112 No. 7, pp. 1757‐828.

Christopher, A.N. (1998), “The psychology of names: an empirical

reexamination”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 28 No. 13,

pp. 1173‐95.

Darity, W. and Mason, P. (1998), “Evidence on discrimination in employment:

codes of color, codes of gender”, The Journal of Economic

Perspectives, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 63‐91.

DiMarco, N. (1974), “Supervisor

‐

subordinate life style and interpersonal need

compatibilities as determinants of subordinate's attitudes toward the

supervisor”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 575‐

8.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

25

Dinur, R., Beit‐Hallahmi, B. and Hofman, J. (1996), “First names as identity

stereotypes”, The Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 136 No. 2, pp.

191‐200.

Elsbach, K.D., Barr, P.S. and Hargadon, A.B. (2005), “Identifying situated

cognition in organizations”, Organization Science, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp.

422‐35.

Fryer, R. and Levitt, S. (2004), “The causes and consequences of distinctively

black names”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 119 No. 3, pp.

767‐805.

Garwood, S.G., Cox, L., Kaplan, V., Wasserman, N. and Sulzer, J. (1980),

“Beauty is only “name” deep: the effect of first

‐

name on ratings of

physical attraction”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 10 No.

5, pp. 431‐5.

Glaman, J., Jones, A. and Rozelle, R. (1996), “The effects of co

‐

worker

similarity on the emergence of affect in work teams”, Group and

Organization Management, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 192‐215.

Goldberg, C.B. (2005), “Relational demography and similarity

‐

attraction in

interview assessments and subsequent offer decisions: are we missing

something?”, Group and Organization Management, Vol. 30 No. 6, pp.

597‐624.

Grimes, D.S. (2002), “Challenging the status quo? Whiteness in the diversity

management literature”, Management Communication Quarterly, Vol.

15 No. 3, pp. 381‐409.

Hammonds, K.H. (2005), “Why we hate HR”, Fast Company, August, pp. 40‐

7.

Joubert, C. (1994), “Relation of name frequency to the perception of social

class in given names”, Perceptual and Motor Skills, Vol. 79, pp. 623‐6.

King, E.B., Madera, J.M., Hebl, M.R., Knight, J.L. and Mendoza, S.A. (2006),

“What's in a name? A multiracial investigation of the role of

occupational stereotypes in selection decisions”, Journal of Applied

Social Psychology, Vol. 36 No. 5, pp. 1145‐59.

Lee, T.W. and Mitchell, T.R. (1994), “An alternative approach: the unfolding

model of voluntary employee turnover”, Academy of Management

Review, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 51‐89.

Leirer, V., Hamilton, D. and Carpenter, S. (1982), “Common first names as

cues for inferences about personality”, Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 712‐8.

Lieberson, S. and Mikelson, K.S. (1995), “Distinctive African American names:

an experimental, historical, and linguistic analysis of innovation”,

American Sociological Review, Vol. 60 No. 6, pp. 928‐46.

Louis, M.R. and Sutton, R.I. (1991), “Switching cognitive gears: from habits

of mind to active thinking”, Human Relations, Vol. 44 No. 1, pp. 55‐76.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

26

McDowell, T. and Jeris, L. (2004), “Talking about race using Critical Race

Theory: recent trends in the Journal of Marital and Family Therapy”,

Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 81‐94.

McPherson, M., Smith‐Lovin, L. and Cook, J.M. (2001), “Birds of a feather:

homophily in social networks”, Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 27,

pp. 415‐44.

Mehrabian, A. (1990), The Name Game: The Decision that Lasts a Lifetime,

Signet Books, New York, NY.

Mehrabian, A. (1992), “Interrelationships among name desirability, name

uniqueness, emotion characteristics connoted by names, and

temperament”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 22 No. 23,

pp. 1797‐808.

Mehrabian, A. (2001), “Characteristics attributed to individuals on the basis of

their first names”, Genetic, Social, and General Psychology

Monographs, Vol. 127 No. 1, pp. 59‐88.

Mehrabian, A. and Piercy, M. (1993a), “Differences in positive and negative

connotations of nicknames and given names”, Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, Vol. 133 No. 5, pp. 737‐9.

Mehrabian, A. and Piercy, M. (1993b), “Affective and personality

characteristics inferred from length of first names”, Personality and

Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 19 No. 6, pp. 755‐8.

Pager, D. (2003), “The mark of a criminal record”, The American Journal of

Sociology, Vol. 108 No. 5, pp. 937‐75.

Palmer, R.J., Welker, R.B., Campbell, T.L. and Magner, N.R. (2001),

“Examining the impression management orientation of managers”,

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 35‐49.

Pettigrew, T.F. and Tropp, L.R. (2006), “A meta

‐

analytic test of intergroup

contact theory”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 90

No. 5, pp. 751‐83.

Ruppel, G. (Producer) (2004), “The Name Game”, ABC's 20/20, August 20,

ABC News, New York, NY.

Sacco, J., Scheu, C., Ryan, A. and Schmitt, N. (2003), “An investigation of

race and sex similarity effects in interviews: a multilevel approach to

relational demography”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88 No. 5,

pp. 852‐65.

Singer, M. and Lange, C. (1994), “Preferential hiring: a managerial

viewpoint”, Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 17‐21.

Smith, F.L., Tabak, F., Showail, S., Parks, J.M. and Kleist, J.S. (2005), “The

name game: employability evaluations of prototypical applicants with

stereotypical feminine and masculine first names”, Sex Roles, Vol. 52

No. 12, pp. 63‐82.

NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be

accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2008): pg. 18-39. DOI. This article is © Emerald and permission has been

granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be

further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald.

27

Turban, D.B. and Jones, A.P. (1988), “Supervisor

‐