Evaluation of the School Based

Supply Cluster Model Project

Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg.

This document is also available in Welsh.

© Crown Copyright Digital ISBN 978-1-83933-398-9

SOCIAL RESEARCH NUMBER:

50/2019

PUBLICATION DATE:

12/11/2019

Evaluation of the School Based Supply Cluster Model Project

Author(s): Brett Duggan, Alison Glover and Tanwen Grover,

Arad Research, and Annalisa Feehan.

Full Research Report: Duggan, B., Glover, A., Grover, T. Feehan, A. (2019).

Evaluation of the School Based Supply Cluster Model Project. Cardiff: Welsh

Government, GSR report number xx/201x.>

Available at: https://gov.wales/evaluation-school-based-supply-clusters

Views expressed in this report are those of the researcher and not

necessarily those of the Welsh Government

For further information please contact:

Katy Marrin

Social Research and Information Division

Welsh Government

Cathays Park

Cardiff

CF10 3NQ

Email: [email protected]

1

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank all of the supernumerary teachers,

headteachers, school senior managers and other stakeholders who took part

in the interviews and survey. The authors would also like to thank,

Welsh Government officials, Gail Deane, Lucy Durston (Education and

Public Services Group), and Katy Marrin (Knowledge and Analytical

Services) for their guidance and support.

Mabon ap Gwyn at Arad Research who coordinated fieldwork and

assisted with presenting survey results.

2

Contents

List of tables…………………………………………………………….………………….……….3

List of figures………………………………………………………………………….……………3

Glossary ................................................................................................................................. 4

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5

2. Methodology .............................................................................................................. 8

3. Project context ........................................................................................................ 12

Policy context ................................................................................................................... 12

Project objectives ............................................................................................................. 15

Approaches used to provide supply cover in cluster schools prior to the Project ............. 15

4. Management and delivery ....................................................................................... 17

Engagement and recruitment ........................................................................................... 17

Delivery models adopted by the clusters .......................................................................... 20

Monitoring and evaluation ................................................................................................ 27

5. Project outcomes .................................................................................................... 28

Teaching and learning ...................................................................................................... 28

Wider school improvement ............................................................................................... 33

Cluster collaboration ......................................................................................................... 37

Supernumerary teachers .................................................................................................. 42

Efficiencies and financial benefits ..................................................................................... 50

6. Sustainability ........................................................................................................... 54

7. Conclusions and issues for future consideration ..................................................... 58

Annex A: Research tools ..................................................................................................... 67

Annex B: Summary of cluster school online survey responses (Spring 2019) ..................... 85

Annex C: Pilot cluster case studies ...................................................................................... 96

3

List of tables

Table 2.1: The pilot school clusters and completed interviews. ........................................... 11

Table 4.1: The strengths and challenges of the different delivery models. .......................... 26

Table 5.1. Overview of the cost comparison to provide supply cover .................................. 51

Table 7.1. Examples of potential tapered intervention support ............................................ 65

List of figures

Figure 4.1: Timeline of cluster engagement with the Project ............................................... 18

Figure 4.2: The structure of each of the pilot clusters. ......................................................... 21

Figure 4.3: Example of block timetable ................................................................................ 23

Figure 4.4: Example of fixed timetable ................................................................................. 24

Figure 4.5: Example of flexible timetable ............................................................................. 24

Figure 4.6: Example of combination timetable ..................................................................... 25

4

Glossary

Acronym/Key word

Definition

ALN

Additional Learning Needs

ASD

Autistic Spectrum Disorder

Cluster lead

Headteacher or senior manager in a school responsible for

coordinating Project activity across a cluster.

CPD

Continuing Professional Development

EAL

English as an Additional Language

Estyn

The education and training inspectorate for Wales which provides

independent inspection and advice on the quality and standards

of education and training provided in Wales.

EWC

Education Workforce Council, the independent regulator in Wales

for teachers in maintained schools, Further Education teachers

and learning support staff in both school and FE settings, as well

as Youth Workers and people involved in work-based learning.

HLTA

Higher Level Teaching Assistant

LSA

Learning Support Assistant

NQT

Newly Qualified Teacher

PE

Physical Education

PPA

Planning, preparation and assessment (time)

QTS

Qualified Teacher Status

SDP

School Development Plan

STEM

Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics

Supernumerary

teacher

A floating teacher employed by one school or a cluster of schools

to provide cover for absent teachers.

WLGA

Welsh Local Government Association, an organisation which

represents the interests and views of local government in Wales.

5

1. Introduction

1.1 In July 2018, Arad Research was appointed by the Welsh Government to evaluate

the School Based Supply Cluster Model Project (the Project). The Project provided

£2.7 million grant funding for two years for 18 school cluster pilot projects in 15 local

authorities to trial approaches to employing recently qualified teachers on a

supernumerary basis to manage absence cover (planned or unplanned).

1.2 Each cluster pilot project allocated a cluster lead school, where the headteacher or

senior manager was responsible for co-ordinating project activity across the cluster;

and acted as the main point of contact with the Welsh Government and the local

authority, and as the employer for the supernumerary teacher/s. One hundred and

three schools were involved in the Project, with 50 supernumerary teacher roles

available; 47 of these posts were filled. During the course of the pilot there have

been school mergers and in some cases more teachers needed to be recruited as

supernumerary teachers secured permanent posts before the end of the Project.

1.3 The Project intended to support workforce capacity by employing recently qualified

teachers to the posts advertised by clusters. Local authorities and schools are

responsible for maintaining effective staffing within schools and making decisions

around delegated staffing budgets and this pilot Project supported this approach.

The financial support given to clusters was tapered over the project period: during

Year 1 (from September 2017) clusters were provided with grant funding to cover

100 per cent of the project’s costs; during Year 2 (from September 2018) clusters

were provided with grant funding for 75 per cent of costs. Although no grant funding

was available to clusters into the third year, the intention was that arrangements

would be sustainable, with schools continuing to employ supernumerary teachers

on a self-financing basis at either local authority or school cluster level from

September 2019.

1.4 Although the Project was initially intended to be operational from September 2017, it

was decided that the start date would be delayed until after the start of the

academic year, later than September 2017, so that the Project would not cause any

disruption to the normal job market and work opportunities for recently qualified

teachers in securing permanent positions.

6

1.5 The aims of this evaluation were to:

Review the implementation and delivery of the Project;

Assess and provide advice on project monitoring and reporting;

Assess how the projects have contributed to the broad outcomes of the Project

and their own objectives; and

Make recommendations regarding future models of supply delivery in Wales and

whether arrangements for collaborative direct employment model should be

extended/ encouraged.

1.6 In recent years, a number of reports

1

have explored issues surrounding the

deployment and management of supply teachers and the impact on learner

outcomes. In May 2015, in response to the Children, Young People and Education

Committee’s inquiry into supply teaching

2

, a Supply Model Taskforce was

established to consider future delivery options for commissioning supply teachers in

Wales. From September 2019, the National Procurement Services Supply Teachers

Framework for Wales will apply, with schools encouraged to use agencies

complying with the framework, which includes a minimum pay point for supply

teachers

3

.

1.7 The Taskforce was charged with reviewing national and international models of

delivery for the supply workforce, engaging with key stakeholders to take evidence

with a view to recommending alternative delivery options going forward. The

Taskforce reported with recommendations in February 2017

4

. Several of the

recommendations advocated greater support for recently qualified teachers who

found themselves in short term supply roles and the introduction of a collaborative

approach to delivery. The School Based Supply Cluster Model Project was

developed in response to these recommendations.

1

Estyn (2013) The impact of teacher absence; Wales Audit Office (2013) Covering Teachers’ Absence;

National Assembly for Wales (2014) Covering Teacher’s Absence

2

National Assembly for Wales (2015) Inquiry into Supply Teaching

3

Welsh Government (2019) The National Procurement Services Supply Teachers Framework for Wales

4

Ministerial Supply Model Taskforce (2017) Report to the Cabinet Secretary for Education

7

1.8 The evaluation addressed the following research questions:

1. What different models of supply delivery have been developed?

2. Are project monitoring systems appropriate for assessing the progress and

outcomes of projects?

3. How can the cost savings and efficiencies of the Project be assessed?

4. What barriers and facilitators to collaborative working have been experienced

by clusters?

5. To what extent have clusters delivered against the broad outcomes of the

Project?

6. To what extent have clusters met their own objectives?

7. To what extent have clusters contributed to school improvement activities?

8. Are clusters self-sustaining in year three (2019/20)?

9. Should and how could local authorities and Welsh Government support such

initiatives in the future?

1.9 The pilot nature of the Project offers significant opportunity for learning both in terms

of reforms to the current education system in Wales and impetus for collaborative

regional working with schools considering alternative ways of meeting supply

needs, which could be sustainable in the longer term. This independent evaluation

delivers an assessment of the design, implementation and outcomes of the Project

and aims to provide learning for future policy and practice in this area.

1.10 The report presents the findings from the research activity conducted from

September 2018 to July 2019, and focuses on the implementation and impact of the

Project during years 1 and 2. A short follow-up report will be published in

September 2020, which will be informed by surveying cluster leads and

supernumerary teachers, exploring longer-term impact of the Project, reporting on

any changes in the way schools address their supply needs and the impact of the

supernumerary role on teachers’ employment experience. The follow-up report will

also contain a final cost effectiveness analysis, as the final monitoring data

submission from clusters was not available for this report.

8

2. Methodology

2.1 A mixed methods approach was undertaken, with opportunities provided for all

clusters and key stakeholders to contribute at various points during the evaluation.

The evaluation drew on data from multiple sources including monitoring data,

primary qualitative data and quantitative data, which provided opportunity for deeper

analysis and the corroboration of findings. During the scoping phase of the

evaluation all project documentation such as project background information and

clusters’ applications for the grant funding were examined. As the Project

progressed all clusters submitted termly monitoring forms, which included data on

the number of supernumerary teachers employed, the total number of absence

days that required cover in the cluster, the cost of agency supply cover and the

number of days covered by the supernumerary teachers. End of year reports

summarised each cluster’s delivery of the Project and reported impact; and these

were also shared with the research team. Primary data was collected during

interviews where the perspectives of senior managers, supernumerary teachers and

other relevant stakeholders provided insights into the Project’s design, planning and

delivery. Table 2.1 provides an overview of all contributors and how the information

was collected. More detail of the various stages of data collection is provided below.

2.2 As a first stage of the evaluation, a series of stakeholder interviews was carried out,

focusing on the policy context and background to the Project, its aims, design and

delivery to date. Interviews were carried out with Welsh Government officials (3),

Estyn (1), Education Workforce Council (EWC) (2), Welsh Local Government

Association (WLGA) (1) at the beginning of the evaluation, and with local authority

representatives (3), other headteachers and deputy headteachers (8), Newly

Qualified Teacher (NQT) mentors (2) and learners (4) later on in the evaluation

process. All interviewees invited to participate in the evaluation were given the

opportunity to participate in the language of their preference, with interviews

conducted by telephone or face to face. The outcomes of the scoping interviews

were used to inform the ongoing design and delivery of the evaluation, providing

further context to the Project and identifying supplementary questions to be asked

9

during fieldwork with cluster leads, supernumerary teachers and other participating

schools.

2.3 The monitoring forms submitted by clusters were used to establish the cost

effectiveness of the Project. The total number of cover days needed and the cost of

this cover provided by agencies, along with the number of days covered by the

supernumerary teacher/s were used to work out the total spend on cover if the

cover provided by the supernumerary teachers had been provided by agency

supply. The average daily supply cost for the agency cover used by clusters was

also calculated (Section 5).

2.4 A key aim of the evaluation was to ensure good levels of engagement with

participating clusters and to understand their experiences of the Project at different

points in time. Cluster leads were invited to take part in interviews in autumn 2018

and interviews were completed with all 18 cluster leads. These discussions focused

on project delivery to date, how supernumerary teachers were deployed,

collaboration with cluster schools, support for supernumerary teachers’ professional

development, and any barriers or challenges faced. Further interviews were carried

out during summer 2019 with 17 out of the 18 cluster leads: these interviews

focused on project management over the course of the Project, and its impact on

learners, on supernumerary teachers, on wider school staff and the contribution to

wider school priorities. The information collected during these summer 2019

interviews was used to inform all clusters’ end of year 2 reports.

2.5 Telephone interviews were completed with 25 supernumerary teachers from across

15 clusters. These interviews provided insights into teachers’ motivation for

applying, recruitment processes, models of deploying teachers, management,

professional development, experiences of working across different schools and key

stages, benefits, and future plans. The research team gained consent to re-contact

the supernumerary teachers by telephone or email for follow-up interviews during

the 2019/20 academic year to record whether, and where they are teaching post-

Project.

10

2.6 In addition, an online survey was designed to collect the views of other schools

involved in the Project. The survey explored similar topics to those discussed with

cluster leads. 34 out of 85 schools (excluding cluster leads who were not invited to

complete the survey) responded. When appropriate, links to the survey findings are

included in the narrative of this report, referenced as supporting data from other

cluster schools/headteachers.

2.7 Table 2.1 provides a breakdown of the numbers of individuals who contributed to

the various stages of the evaluation outlined above. All interview schedules are

included in Annex A and a summary of the online survey results are presented in

Annex B. Case studies were also developed to present further detail on specific

themes to emerge during the evaluation, such as managing a large cluster of

schools, recruiting and deploying specialist cover for Welsh-medium schools and

Special schools. As a result, the case studies reflect the Project experience across

different parts of Wales and in different types of schools. Information for these case

studies was collected during half day visits to the cluster lead school and telephone

interviews. Cluster leads, other headteachers and other relevant stakeholders such

as NQT mentors, and local authority representatives contributed to the development

of the case studies. Annex C contains the full case studies, which are also

referenced as appropriate throughout the report.

11

Table 2.1: The pilot school clusters and completed interviews.

Cluster

No. of

schools

in

cluster

No. of

SN*

teacher

roles

Completed interviews

Survey

Cluster leads

SN*

teachers

**Other

stakeholders

Cluster

schools

Spring

2019

Autumn

2018

Summer

2019

Spring

2019

Blaenau

Gwent A

5

4

1

1

1

Blaenau

Gwent B

6

2

1

1

2

Caerphilly

7

1

1

1

2

1

4

Cardiff

10

10

1

1

4

3

3

Carmarthen

7

3

1

1

2

Conwy A

6

4

1

1

4

Conwy B

6

3

1

1

3

3

Merthyr

Tydfil A

7

1

1

1

1

2

Merthyr

Tydfil B

7

1

1

1

1

Monmouthshire

1

1

1

1

1

Neath Port

Talbot

10

5

1

1

2

1

5

Newport

2

1

1

1

1

3

1

Pembrokeshire

3

3

1

2

Powys

6

1

1

1

1

4

Rhondda

Cynon Taff

2

2

1

1

1

1

Torfaen

4

2

1

1

1

2

Vale of

Glamorgan

6

1

1

1

1

Wrexham

8

2

1

1

2

8

3

103

47

18

17

25

17

34

Note: Some cluster schools merged during the course of the Project; individual schools have not

been named as only the names of the local authorities participating in the pilot Project were

announced by the Welsh Government.

*SN – Supernumerary

**includes NQT mentors, headteachers, local authority education officers and learners.

12

3. Project context

Policy context

3.1 In September 2017, the Welsh Government stated in their Action Plan for Education

in Wales that ‘Education has never been more important. Education reform is our

national mission’

5

. Strengthened teacher training delivery, new professional

standards for teachers

6

, the National Academy for Educational Leadership

7

and the

implementation of Successful Futures

8

with the development of the new curriculum

for Wales

9

, all underpin this education reform for Wales. A key objective to be

achieved by 2021 is the establishment of more effective workforce planning

systems, which includes developing ‘alternative models to ensure the quality and

sufficiency of supply teachers for schools’

10

.

3.2 Collaborative working between schools is also key for progressing professional

learning for teachers

11

and for schools to develop as learning organisations

12

and

this pilot Project contributes to further progress in these areas. The Welsh

Government also has responsibility to ensure all employment practices are lawful

and ethical

13

, and the introduction of the National Procurement Services Supply

Teachers Framework for Wales

14

will be revised on a geographical lot basis and will

be active from September 2019. This Framework includes a minimum pay point,

transparency of fees and the abolition of particular working practices, with

professional learning and induction support required and will provide schools with ‘a

greater degree of choice and flexibility in which supply agencies to work with’

15

.

5

Welsh Government (2017) Education in Wales: Our national mission Action plan 2017-21. p. 2.

6

Welsh Government (2019) Professional standards for teaching and leadership.

7

National Academy for Educational Leadership Wales

8

Donaldson, G. (2015) Successful Futures: Independent Review of Curriculum and Assessment

Arrangements in Wales

9

Welsh Government (2019) Curriculum for Wales 2022

10

Welsh Government (2017) Education in Wales: Our national mission Action plan 2017-21. p. 4.

11

University of Wales Trinity Saint David (2018) The National Approach to professional learning in Wales:

Evidence base.

12

OECD (2018) Developing schools as learning organisations in Wales: highlights

13

Welsh Government (2016) Code of Practice Ethical Employment in Supply Chains.

14

Welsh Government (2019) The National Procurement Services Supply Teachers Framework for Wales

15

Welsh Government (2019) Supply teachers Guidance

13

Twenty-seven supply agencies are part of this Framework and schools are being

encouraged to use it to source supply teachers.

3.3 Several challenges have been highlighted regarding the management of supply

teachers and the impact on learners in Wales. The collaborative Estyn and Wales

Audit Office reports noted the negative impact of supply teaching on learner

progress and behaviour and difficulties encountered by supply teachers to establish

effective working relationships with learners. The difficulty schools face sourcing

Welsh speaking supply teachers, those able to fulfil roles in rural or economically

deprived areas, or those able to teach shortage subjects such as mathematics and

physics was also reported

16

. It was also noted that appropriate professional

development was lacking for those engaged as supply teachers, hindering teachers

securing a permanent post

17

.

3.4 In May 2015, a Supply Model Taskforce was established to consider the future

delivery options for commissioning supply teachers in Wales. The Taskforce found

that supply provision was often variable and inconsistent; with supply teachers paid

different rates of pay and experiencing different terms and conditions dependent on

how they were employed. These were not always commensurate with the terms of

the nationally agreed School Teachers' Pay and Conditions Document

18

or the

qualifications, skills and experience held by supply teachers. Teachers on short

term supply may not be able to access learning and professional development

opportunities in the same way that those on longer term supply contracts can and

there may be retention issues among NQTs employed as supply teachers. With one

in ten of the Welsh teaching workforce working as a supply teacher, and of those a

third have been in the profession less than five years, with just over a fifth not

having completed their induction year

19

, the pilot Project provided opportunity to

support NQTs to complete their induction year requirement and deliver ongoing

professional development.

16

Estyn (2013) The impact of teacher absence. p. 3-4.

17

Estyn (2013) The impact of teacher absence. p. 5.

18

Department for Education (2018) School teachers’ pay and conditions document 2018 and guidance on

teachers’ pay and conditions.

19

Education Workforce Council (2016) An analysis of registered supply school teachers. p. 2-5.

14

3.5 The Taskforce report made a number of recommendations in light of the issues

highlighted above including one related to the development and trialling of a

regional collaborative model for the delivery of supply teaching. Such an approach

was viewed as having the potential to address some of the specific difficulties

experienced in a number of areas by deploying recently qualified supply teachers in

clusters of schools to meet the demand for absence cover (planned and unplanned)

often at short notice.

3.6 There are also wider policy developments within Wales which run alongside this

pilot Project. The powers to determine Teachers’ Pay and Conditions were formally

transferred to Welsh Ministers in September 2018. In July 2019 the Minister for

Education announced an increase in pay for newly qualified school teachers from

September 2019, as well as an increase for all other school teachers

20

. This

followed recommendations made by the Independent Welsh Pay Review Body

aimed at raising the status of the profession and supporting the recruitment and

retention of high-quality teachers and leaders

21

.

3.7 Another current priority for the Welsh Government is the work of the Managing

Workload and Reducing Bureaucracy Group, which is looking at managing

workforce well-being and workload

22

. This Group’s priorities are to develop a

workload and well-being toolkit for the school workforce, to promote reducing

workload resources, to develop training models and exemplar case studies and to

carry out a sector-wide audit.

3.8 In May 2019, the Fair Work Commission’s report Fair Work Wales was published.

The report made a number of recommendations relating to Welsh Government’s

role in the fair work agenda

23

. Welsh Government will now be establishing a Social

Partnership and Fair Work Directorate to drive forward fair work in Wales.

3.9 This pilot Project reflects the ambitions of the above policy developments, working

to ensure the education workforce (including supply teachers) is provided with

20

Announcement of teacher pay rise as teacher pay devolved to Wales - July 2019

21

Independent Welsh Pay Review Body, First Report – 2019

22

Plenary Statement 11 June 2019

23

Plenary Statement 7 May 2019

15

opportunities for fair work, effective well-being and workload support and a

minimum standard for professional learning provided for supply teachers.

Project objectives

3.10 Welsh Government identified broad outcomes of interest relating to the extent to

which the pilot Project:

Implements alternative and innovative arrangements that address school

absence cover (planned and unplanned absence);

Supports NQTs in short term supply roles in terms of professional development

and retention;

Aids efficiencies, evidence added value and potential cost savings against the

school;

Promotes best practice in collaboration and joint working across school clusters.

Approaches used to provide supply cover in cluster schools prior to the

Project

3.11 Cluster schools commonly used external supply agencies to address their supply

needs. In some cases, cluster schools had built positive relationships with particular

supply agencies to facilitate the process. Some cluster schools also commonly used

various internal supply options to address their supply needs. In particular, smaller

primary schools were more likely to use internal cover exclusively, due to these

schools not having a dedicated external supply budget. Internal supply options

commonly included the use of cover supervisors and Higher Level Teaching

Assistants (HLTAs). Insurance was also available to cluster schools in certain

circumstances (such as when staff absence extended beyond five days) and one

cluster had developed its own internal insurance mechanism. Yet it is important to

note that schools’ insurance policies varied. The survey completed by other cluster

schools provides an overview of approaches used by some of the schools to cover

absence (see Annex B).

16

3.12 Cluster schools reported that, prior to the commencement of the Project, they were

facing a number of common challenges linked to supply, most notably: the rising

costs of supply cover, particularly when school budgets are under pressure; the

reduced quality of teaching provided through supply cover; challenges accessing

specialised supply such as Welsh-medium supply teachers or supply teachers

experienced in supporting pupils with additional learning needs, (see Case studies 2

and 4 for further discussion on this issue) and the burden of spending time on

supply management instead of on other school priorities.

3.13 Many clusters were able to build on previous partnership working and collaboration

(such as collaboration on transition or school improvement, or a shared attendance

officer) however this prior partnership working did not include joint approaches to

supply cover.

17

4. Management and delivery

4.1 This section discusses the management and delivery of the Project, including initial

engagement and recruitment; delivery models; and monitoring and evaluation.

Engagement and recruitment

Key findings

Local authorities were informed about the Project in July 2017.

Some schools facing particular supply challenges were targeted.

Recruitment of supernumerary teachers took longer than anticipated for some

clusters.

Some clusters were unable to access the full 100 per cent funding for the full

first year, due to delayed start.

Some supernumerary posts required re-advertising when teachers secured

permanent jobs during the Project.

4.2 The timeline for the announcement and implementation of the Project is

summarised in Figure 4.1. The Welsh Government invited local authorities to submit

expressions of interest in taking part in July 2017. Subsequently, local authorities

informed clusters about the Project, in some cases targeting schools they were

aware faced particular supply challenges (e.g. accessing Welsh-medium supply

cover) or identifying clusters deemed to be well-placed to deliver the Project.

However, an initial delay to the start date of the Project (with schools able to start

recruiting only in the autumn) resulted in clusters initiating recruitment processes a

few months into the 2017-18 academic year. As a result some clusters were unable

to access the full 100 per cent grant funding for the full first year of the Project.

18

Figure 4.1: Timeline of cluster engagement with the Project

19

4.3 Recruitment took longer than some cluster lead schools had anticipated, with

repeated rounds of advertising before appointing supernumerary teachers in some

cases. Schools reported receiving fewer applications than expected for the

supernumerary posts (based on previous recruitment experience), which some

attributed to the time of year. In some cases this led to delayed start dates. Cluster

lead schools reported that greater lead-in time would have been helpful, as well as

the opportunity to recruit for the start of the academic year.

4.4 A minority of supernumerary teachers secured permanent positions (either within

the cluster or elsewhere) during the pilot period. In each case, clusters have re-

advertised and have not faced many challenges in replacing these supernumerary

teachers. Although clusters report that re-advertising and recruit anew to these

posts has disrupted project delivery, schools also recognise that providing a route

into full-time teaching posts is a measure of the Project’s success.

4.5 All clusters outlined their anticipated outcomes for the Project, with some clusters

identifying national/regional priorities that the Project would help support, including:

The development of the Curriculum for Wales

24

;

Contributing towards establishing a self-improving school system;

ALN transformation programme

25

;

Providing support for More Able and Talented learners;

Reducing the attainment gap.

4.6 For other clusters, proposed outcomes supported school-based or cluster-wide

priorities, such as:

Building capacity across the cluster;

Cost savings for supply cover;

Continuity of provision through the deployment of supernumerary teachers;

Improved learner outcomes – progress, attainment, literacy/numeracy/digital;

Improved school-to-school working – collaboration, sharing good practice;

Improved quality of teaching;

24

Welsh Government (2019) Curriculum for Wales 2022

25

Welsh Government (2017) Additional learning needs (ALN) transformation programme

20

Enhanced professional development of supply teachers;

School Development Plan (SDP) priorities;

Staff wellbeing;

Sustainability.

Delivery models adopted by the clusters

Key findings

The number of schools and supernumerary teachers in each cluster ranged

from one to ten.

Clusters welcomed the flexibility and autonomy they had to design and

implement the Project.

The different delivery models adopted by clusters;

o Block timetable (half or whole term in each school)

o Fixed weekly/fortnightly timetable in several schools

o Flexible timetable according to demand

o Combination of flexible and fixed

4.7 A range of delivery models was adopted by clusters, with a range in the type of

school that have served as cluster leads (i.e. clusters have been led by primary,

secondary, middle and special schools). As illustrated in Table 2.1 the configuration

and structure of each cluster also varied. The number of both the schools and the

supernumerary teachers in each cluster ranged from one to ten. Figure 4.2 provides

an overview of the structure of each pilot cluster.

4.8 Welsh Government gave clusters flexibility regarding the approach they took for the

Project, the number of supernumerary teachers to be employed and the number of

schools which would form the cluster. This autonomy was welcomed by cluster

leads and the other headteachers in the clusters, with the diversity of approaches

adopted by clusters reflecting this. The delivery model of each pilot cluster was

decided by cluster leads and other cluster headteachers during the design stage.

Key decisions included:

Who would manage and mentor the supernumerary teacher/s;

21

How would the supernumerary teacher/s be shared between the cluster schools

(proportion of time in each school and timetabling approach e.g. set blocks in

each school or weekly timetable); and

What type of cover would the supernumerary teacher/s be providing (e.g.

sickness or for planning, preparation and assessment time (PPA)).

Figure 4.2: The structure of each of the pilot clusters

22

4.9 Clusters adopted a range of approaches and, following feedback from

supernumerary teachers and cluster schools, a couple of clusters altered their

approach for the second year. It is possible to identify four different models based

on the timetabling approach clusters used for the supernumerary teachers;

1. A block timetable, based on supernumerary teachers spending a half term or

whole term in each cluster school

2. Fixed weekly or fortnightly timetable in several cluster schools

3. Flexible deployment, led by demand from the cluster schools

4. Combination of fixed and flexible approaches

4.10 Block – half or whole term timetable. Some of the clusters allocated the

supernumerary teacher to each of their cluster schools for a term, with the teacher

teaching in the smaller cluster schools for half a term. This approach proved useful

for one cluster (see Figure 4.3), as the supernumerary teacher was able to observe

teaching and behaviour management in the larger cluster school at the beginning of

the process, before spending at least a half term in each of the other cluster

schools. Another cluster only applied this approach at the beginning; following a

week of preparation time, the supernumerary teacher taught each Year 7 class for a

week, using more of a ‘primary teaching approach’ to support learners’ transition to

secondary school. This meant that the secondary school received their full

allocation of supernumerary hours at the beginning of the Project. However, as

movement between the cluster schools was less frequent for the supernumerary

teacher, sharing of practice and collaborative work was less apparent over the short

term.

23

Figure 4.3: Example of block timetable

Powys Cluster

Allocation

Management

6 schools

1 teacher

All rural/semi-rural primary schools

The teacher was allocated to each

school in the cluster for a full term

each, but with the two smaller schools

sharing over a term. The first term was

spent in the larger school, observing

teaching and behaviour management to

‘develop ground rules as to what was

acceptable’, this was then transferable

to the other cluster schools.

4.11 Fixed weekly or fortnightly timetable. Pilot clusters that allocated supernumerary

teachers using a fixed timetable assigned teachers to cluster schools for an agreed

number of days each week or fortnight. The teacher’s role at a school could vary;

teaching the same class each week or covering some regular classes with other

time allocated according to the need in the school at the time (e.g. sickness cover,

staff professional development). Adopting this format allowed clusters to release

staff on a regular timetable to work on school-level priorities or for PPA time. This

model also allowed the supernumerary teachers to deliver specific projects to all

cluster schools on a regular basis e.g. STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering

and Mathematics) or PE (Physical Education) focused cluster projects. Even where

clusters adopted a more flexible approach based on demand, some cluster schools

chose to request the teacher for the same day each week (or similar), to help them

maintain momentum and consistency in classroom teaching. An example of this

approach is provided in Figure 4.4.

For her first staff

meeting at each school

we wanted to learn

about what she had

been doing, what had

she seen? And what

did she think worked

well? (Cluster lead)

24

Figure 4.4: Example of fixed timetable

Carmarthenshire

Cluster

Allocation and role

Benefit of the model

7 schools

3 teachers

Each teacher had a regular

timetable, teaching in two or

three schools each week. Cover

was provided for management

duties, INSET, transition projects,

triad working and sickness

absence. For example one

teacher focused on PE, and

delivered sessions in the primary

schools and organised events at

the secondary school.

4.12 Flexible according to demand from the cluster schools. A further model used less

frequently by clusters was a flexible model, allowing cluster schools to book

supernumerary teachers’ time as and when they were needed to provide cover.

This model was usually administered either through an online booking calendar

(see Figure 4.5) or through a central administrator in the cluster lead school. This

model lent itself to short-notice cover (such as sickness absence) but was also used

to book supernumerary teachers’ time ahead of time and/or on a regular basis. As

such, this flexible model could still be used in much the same was as a fixed

timetable if cluster schools chose to book supernumerary teachers’ time on a

regular schedule. Clusters found that this approach could effectively meet the needs

of cluster schools as they arose but could potentially be more burdensome to

administer. Equitable division of the supernumerary teachers’ time between cluster

schools needed to be monitored within this model.

Figure 4.5: Example of flexible timetable

Pembrokeshire Cluster

Allocation and role

3 schools 3 teachers

The secondary school had the administrative capacity

to manage the project. Time between the schools was

allocated according to pupil numbers. An online

booking calendar through Hwb was used for planned

cover, with teachers re-allocated when an emergency

cover was needed.

Without the project we

would have had much

less school self-

evaluation and

monitoring going on;

this year we have been

able to do more than we

usually do.

(Cluster lead)

25

4.13 Combination of fixed and flexible. Pilot clusters which used a combination of both a

fixed and a flexible timetable usually took one of two approaches: allocating each of

the supernumerary teachers a partial fixed timetable, with the remaining time

allocated flexibly to meet demands; and/or allocating a fixed timetable to one

supernumerary teacher and a more flexible timetable to another supernumerary

teacher. This model allowed regular release of staff to focus on school priorities

and/or PPA while maintaining an element of responsiveness to school needs. An

example of this model is provided in Figure 4.6.

Figure 4.6: Example of combination timetable

Blaenau Gwent Cluster

Allocation and role

5 schools 4 teachers

Within the learning community, teachers were used to

cover sickness absence and cross-phase activity in the

primary phase, and the teacher in the secondary phase was

allocated a partial fixed timetable in the learning resource

base (with the remaining time dedicated to sickness and

CPD (Continuing Professional Development) cover). In

other cluster schools, teachers covered for sickness

absence, PPA and transition activities.

4.14 Table 4.1 provides an overview of the common strengths and challenges associated

with the different models of delivery. Other strengths and challenges associated

with Project delivery relate more specifically to the nature of individual cluster

projects; for example, the teaching background of supernumerary teachers may

dictate which key stages they are comfortable covering, or a cluster school may

wish to use the supernumerary teachers primarily for sickness absence cover,

which may not be possible if the cluster as a whole is using a fixed timetable to

allocate their time. The survey of other cluster schools (see Annex B) also found

that the majority of schools found the deployment of the supernumerary teachers to

be satisfactory; for example, ‘all schools got a fair allocation of the supply teachers

and were able to build up good professional relationships with them’ (headteacher).

26

Table 4.1: The strengths and challenges of the different delivery models

Delivery model

Strengths

Challenges

Block timetable

Working relationships with staff

and learners developed

quickly.

Consistent procedures for

supernumerary teacher.

Less opportunity to share

practice between schools on

an ongoing basis.

Fixed

weekly/fortnightly

timetable

Class teachers released

regularly to focus on school

priorities.

Consistency for

supernumerary teachers and

learners.

Less flexibility to respond to

short-notice / emergency

cover needs.

Opportunity for NQT

observation/assessment with

regular classes.

Flexible timetable

Cover could be provided at

short notice.

Can be burdensome to

administer.

Monitoring of equitable share

needed.

Difficult to ensure NQT

induction requirements were

met.

Combination

timetable

Regular PPA cover provided.

Flexibility for emergency cover

available.

Ensuring opportunities for

NQT observations were

fulfilled.

27

Monitoring and evaluation

Key findings

Cluster leads reported the monitoring of the grant by the Welsh Government

was flexible.

Cluster leads reported that the monitoring requirements were proportionate to

the amount of financial support received.

Occasionally there were some challenges experienced by clusters in collating

monitoring data.

The end of year one reports varied in the level of detail provided by clusters.

A template and support were provided for the end of year two report.

4.15 Cluster lead schools were generally positive about the flexibility with which the

Welsh Government had approached the monitoring of the grant. While regular

monitoring was required, cluster lead schools generally reported that they and the

Welsh Government had approached the Project as a pilot, allowing clusters to act

flexibly and trial approaches while maintaining overall general monitoring.

4.16 On the whole, cluster lead schools found the monitoring requirements (in particular,

claim forms) proportionate to the amount of financial support received as part of the

Project. Clusters did face some challenges in collating and submitting monitoring

data on occasion, such as: ensuring data was gathered consistently from all cluster

schools; ensuring the way in which supernumerary teachers had been deployed

was logged appropriately; and ensuring school-level data could be translated into

claim form sections correctly.

4.17 Clusters were also required to submit end-of-year reports summarising the progress

and impact of their pilot project. There was no specific template for these reports

and so reports at the end of the first year were varied, with some clusters providing

a greater level of detail than others. Arad Research supported clusters with this

process (including providing a template) for the second end-of-year report.

28

5. Project outcomes

5.1 This section discusses the outcomes and impact of the Project. Specifically, it

reports on key findings relating to teaching and learning; wider school improvement;

cluster collaboration; impact on supernumerary teachers; and efficiencies and cost

savings.

Teaching and learning

Key findings

Cluster leads and other cluster headteachers reported that the Project has had

a positive effect on teaching and learning.

Cluster leads and other cluster headteachers reported that the positive impact

of the Project on teaching and learning stems from supernumerary teachers

being integrated into staff teams and providing consistency in teaching and

learning.

Over time supernumerary teachers have increasingly been given fixed

timetables or have taken on responsibility for classes on a more regular basis,

making a positive difference to pupil progress.

The Project has led to greater consistency of teaching, supporting the

emotional well-being of learners and providing a more stable and better quality

learning experience for pupils.

Supernumerary teachers have helped support effective transition and

progression of teaching and learning between key stages.

Clusters felt that having teachers work across primary and secondary schools

encouraged them to plan more strategically across phases, leading to benefits

to teaching and learning.

Supernumerary teachers have made a positive difference to behaviour by

becoming familiar with and applying schools’ behaviour management

approaches.

The Project has been used by some clusters to support ALN provision,

impacting positively on learners.

29

5.2 Cluster leads and other cluster school headteachers reported that the Project has

had a positive effect on teaching and learning. By becoming immersed in school life,

supernumerary teachers have come to understand schools’ teaching and learning

strategies and have supported their delivery. Cluster leads reported, quite early in

the Project, that the pilot Project had led to increased quality of teaching, compared

with supply teachers sourced through traditional supply routes. One school reported

that this had resulted in fewer complaints from parents about the impact of supply

cover on their children’s learning. Teachers whose classes were frequently covered

by supernumerary teachers were reassured that experienced teachers who

understood their pupils were delivering their lessons. One cluster lead noted:

‘Without this Project classes may have been covered by HLTAs or cover teachers

who are not familiar with the school, the learners or the data tracking systems. The

consistency has been hugely valuable’.

5.3 Cluster leads and other cluster school headteachers reported that the positive

impact of the Project on teaching and learning stems from supernumerary teachers

being integrated into staff teams and providing consistency in teaching and learning.

It was also reported that as supernumerary teachers become established in a

school or in several schools, their lesson planning and pedagogy improve. ‘The

most successful aspect of the Project has been the quality of teaching and learning

across the phases and standards as a whole’ (Cluster lead). Cluster leads valued

the fact that supernumerary teachers came to understand exactly what was

expected of them to become well-prepared and independent teachers. Cluster lead

schools also reported that the Project helped alleviate pressure on other teachers,

knowing that when they had to be away from their class that ‘learners were in safe

hands because the teacher had built relationships with the children, which is first

and foremost the most important thing’ (Cluster lead). Invariably, cluster leads and

headteachers in other schools compared the model favourably with other supply

cover arrangements.

5.4 During the second year of the Project, in particular, many supernumerary teachers

were given fixed timetables or took on responsibility for classes on a more regular

basis. Some clusters planned to use supernumerary teachers’ subject specialisms,

which has impacted positively on the quality of teaching and on learners’ progress.

30

This includes in Welsh-medium secondary schools, where supernumerary teachers

brought skills in specialist subject areas where there has traditionally been a

shortage of teachers. Indeed headteachers in participating Welsh-medium schools

– primary and secondary – reported continuing challenges in sourcing good quality

supply teachers. The Project has contributed towards filling a gap in this sector. The

Project has been seen as an investment in the quality of supply teachers, as well as

in capacity.

5.5 The Project has led to greater consistency of teaching, supporting the emotional

well-being of learners and providing a more stable and better quality learning

experience for pupils. On balance, evidence from across the clusters indicates that

the increased quality of provision delivered by supernumerary teachers has made a

difference to learners. This observation by cluster leads was provided early on in

the Pilot Project. A number of cluster leads recognised, however, that it is not

possible to make a direct link between the Project and learning attainment given the

range of other factors that impact on learner progress and outcomes. In some

clusters supernumerary teachers provided support for vulnerable learners and

learners with additional learning needs. This has made a difference as learners

transition into the next phase of education or as they prepare to transition into

adulthood and their lives after school. As a result of the additional capacity provided

through the Project, schools have been able reduce the student: staff ratio.

31

Importance of consistency for quality of teaching and learning

One cluster lead commented on the positive impact of having a consistent

supply teacher for the learners and other teaching staff in the school;

‘When we have had to have supply to supplement it [the cluster supply model],

the children’s learning hasn’t been as good. The children are happy to see a

familiar face and the children respond really well. When children are told that a

cluster teacher is covering a class they can go home settled as they know who

they have got. For children who find change stressful preparing them the day

before regarding who the cover teacher is, is very useful. Easy communication

between the class teacher and the cluster teacher means the cover teacher is

fully informed on issues that could impact the emotional well-being of the

children. The standard of work that children produce is much improved to

regular supply teaching and it is marked appropriately.’ (Cluster lead)

5.6 Supernumerary teachers have helped support effective transition and progression

of teaching and learning between key stages. Supernumerary teachers who have

worked in primary and secondary schools within a cluster have supported improved

planning of provision in Year 7 to enable better progression and avoiding duplication

of learning at the beginning of Key Stage 3. This has been achieved through shared

teaching and learning approaches and collaborative planning involving

supernumerary teachers and core staff teams.

Positive impact on transition: One supernumerary teacher was delivering

year 7 Science and discussed with one of the primary headteachers the skills

that the learners would need in year 7. As a result, some of the Year 6

curriculum was altered, this was welcomed in the primary school, particularly

when the relevance for learners’ progress to year 7 was taken into account.

(Cluster lead)

5.7 Cluster leads felt that having teachers work across primary and secondary schools

encouraged them to plan more strategically across phases, leading to benefits to

teaching and learning. In one example, some of the more vulnerable learners in

32

year 6 were identified and allocated to a supernumerary teacher’s tutor group for

year 7 the following year. ‘Parents were delighted when they saw that the member

of staff their child was going to be with was a teacher who already knew their child.

The learners were also delighted they were to have her as their tutor’. (Cluster lead)

5.8 Supernumerary teachers have made a positive difference to behaviour by becoming

familiar with and applying schools’ behaviour management approaches. Cluster

leads and other cluster school headteachers reported that the relationships formed

between supernumerary teachers and learners led to a reduction in instances of

poor behaviour. This was noted during the early stages of the pilot Project. Cluster

leads also reported that often pupils – particularly older pupils – will ‘test the

boundaries’ when agency-sourced supply teachers are brought in to cover lessons.

This has been less of an issue with supernumerary teachers: schools report there is

greater accountability built into the model (as a result of the teacher being based in

the cluster) and lessons have been more focused and beneficial.

5.9 The Project has been used by some clusters to support ALN provision, impacting

positively on learners. In some clusters, there was a specific focus on supporting

ALN provision. Case study 2 discusses the difficulties Special schools experience

when trying to recruit skilled personnel. Supernumerary teachers have been used to

provide additional capacity to support learners with ALN, both in mainstream

schools and in Special schools involved in the pilot. One Special school used the

Project to cover long-term sickness, providing ‘enormous stability and continuity to a

group of students who would have had rolling supply’. The headteacher in this

school noted the difficulties in finding a teacher through a supply agency with the

right skillset would have been ‘almost impossible’.

5.10 The Project has also led to increased capacity to deliver Welsh-medium ALN

provision in mainstream schools. Through the Project a specialist Welsh-medium

teacher has been released to work across Welsh-medium primary schools,

delivering targeted support to learners. The cluster lead estimates that, as a direct

result of this support, facilitated through the supply clusters pilot, six learners have

been retained in mainstream education who would otherwise have transferred to

special schools. The Project has therefore delivered cost savings by retaining

33

children in mainstream education

26

and enhancing Welsh-medium ALN in

designated Welsh-medium schools, supporting wider policy priorities set out in the

Welsh Government’s additional learning needs (ALN) transformation programme.

Wider school improvement

Key findings

It was common for cluster leads and other cluster school headteachers to

report that without this Project, they would have been unable to release staff to

the same degree.

Some cluster schools chose to release members of staff to focus on

progressing school improvement priorities.

Cluster schools also reported using supernumerary teachers to release staff

for planning / PPA purposes (particularly to support new curriculum and

assessment arrangements).

It was common for cluster schools to use supernumerary teachers to release

staff for professional development (either training courses or school-based

professional learning activities).

Cluster leads were often able to provide examples of the improvements they

had seen within their schools as a result of releasing staff for school

improvement purposes.

There were examples of the supernumerary teacher role directly supporting

school improvement priorities to a greater extent than external supply agency

teachers are able to do.

Cluster leads emphasised the positive impact such additional supply cover

can have on wider staff well-being.

5.11 Rather than using supernumerary teachers to cover short-notice sickness absence,

many cluster schools have tried to make purposeful use of the supernumerary

teachers’ time to gain added value from the Project. This has meant releasing staff

from classrooms to work on more strategic, whole-school improvement activities. It

26

It has been estimated that educating a child in a special school costs approximately £25,000 per annum.

34

was common for cluster schools to report that without this Project, they would have

been unable to release staff to the same degree.

5.12 It was usual for teachers who were released to be allocated particular tasks or

activities to focus upon, relating closely to priorities identified in the school

development plan. Other teachers were released to focus on particular projects,

such as regional collaborative projects. The Project thus provided added supply

capacity and the following are some examples of the ways in which cluster schools

released staff to focus on school improvement priorities include:

Allowing the literacy coordinator to review the school’s literacy provision;

Undertaking learning walks with a particular focus, such as on assessment for

learning;

Undertaking action research relating to school improvement areas;

Planning for improved moderation across the school;

Allowing senior managers to focus on improving evaluation and monitoring

systems across the school;

Allowing senior managers to focus on transition planning;

Establishing school-wide behaviour approaches; and

Supporting a regional formative assessment project.

Addressing school priorities

One cluster lead provided an example of how the Project supported the school

to improve standards; ‘As a school we have found the Project invaluable in

allowing us to provide quality cover immediately for staff illness. However, the

greatest value of the Project has been the ability for school to regularly (e.g.

weekly for [our school]) utilise [the supernumerary teacher] for internal

moderation and standardisation of work within school. This has allowed SLT

and subject leaders to continually monitor and raise standards of teaching and

learning.’ (Cluster lead)

5.13 Cluster schools also reported using supernumerary teachers to release staff for

planning / PPA purposes. This was highlighted as a particularly important element

of preparing the teachers and the school for the new curriculum and assessment

35

arrangements. Examples of the type of activities undertaken by teachers released

for this purpose included cross-curricular planning to meet the requirements of the

new curriculum and planning collaboratively with colleagues (for instance planning

in triads). This type of cross-curricular planning was reported as being challenging

to achieve when teachers are not able to be released from the classroom.

Supernumerary teachers also provided cover for wider PPA requirements which

would ordinarily have been covered through other supply mechanisms.

5.14 In addition, it was common for cluster schools to use supernumerary teachers to

release staff for professional development. This included releasing staff to attend

particular courses (such as training on ALN) as well as to allow them to focus on

their own professional development and professional standards. Examples of the

type of professional development available to teachers released in this way include:

Releasing teachers to address the new professional standards by working

collaboratively with colleagues; observing practice in areas where improvement is

needed; ensuring senior members of staff (such as headteachers) are not called in

to cover PPA time on a regular basis.

5.15 Cluster schools provided examples of the improvements they had seen within their

schools as a result of releasing staff for school improvement purposes. Such

examples include improved self-evaluation processes; establishing monitoring and

assessment processes ahead of time; improved planning for delivering the new

curriculum requirements; improvement in standards following an Estyn inspection;

and consistent leadership to progress key priorities.

36

Impact of the availability of additional cover

One cluster school had invested in ‘Thrive’ (a well-being support programme).

‘Well-being is a big agenda in our school, and there is a lot of work associated

with it and being able to release a member of staff to move those things forward

and knowing we have got scope to do that in an organised way – that we can do

it without there being a negative impact on the class – has been very important

for us’.

The staff were trained during the first year, but there was limited opportunity to

put into practice what staff had learnt from the training. The well-being lead has

been able to focus on that this year, and there is now a comprehensive package

available for pupils. As a result, the school ‘is getting the value out of the money

invested in the training and our pupils are getting the benefit of the expertise

that staff have developed’. (Cluster lead)

5.16 There are also examples of the supernumerary teacher role directly supporting

school improvement priorities to a greater extent than external supply agency

teachers are able to. For example, cluster schools on occasion have been able to

make best use of supernumerary teachers’ existing skillset and expertise to address

particular improvement areas (such as supporting nurture activities). On other

occasions, supernumerary teachers have been able to support extra-curricular

activities (such as residential trips), when external supply agency teachers are

usually unable to do so. Case study 3 provides an example of supernumerary

teachers supporting such priorities. Supernumerary teachers have also been able to

share learning with colleagues in different schools to support professional learning,

having observed teaching and learning in different settings. However, a minority of

headteachers responding to the cluster school survey noted that some

supernumerary teachers were unable to teach Foundation Phase, which limited the

cluster’s ability to meet their intended aims for the Project.

5.17 On occasion, cluster schools emphasised the positive impact such additional supply

cover can have on wider staff well-being. Without such supply cover, cluster schools

reported that teachers would commonly complete school improvement activities

37

(including evaluation activities) in their own time. This is seen to place an additional

burden on teachers who already face a heavy workload; ‘the most successful part of

the Project has been having a spare teacher to release the senior management

team to carry out their role more effectively. In the past, and next year, teachers will

be writing these monitoring reports in their own time, because I can’t afford to

release them – that has been the greatest benefit’ (cluster lead). The survey of

cluster schools also found that the Project had resulted in a positive impact on

workload for staff and other school priorities in some, but not all, cluster schools

(Annex B). Cluster leads and headteachers from other cluster schools also

occasionally commented during interviews that classroom teachers have also

benefitted from increased confidence in the cover available, knowing that they can

take time away from their classroom without detriment to learners’ education.

Cluster collaboration

Key findings

The Project has been effective in strengthening cluster collaboration.

Cluster schools shared effective management approaches.

Supernumerary teachers shared teaching and learning approaches between

cluster schools.

Successful collaborative cluster school projects were completed.

Teachers have been able to lead developments, and take on ownership and

responsibility for initiatives.

There has been a positive impact on transition processes for schools and

learners.

Increased motivation to engage in future collaborative working between cluster

schools.

5.18 The Project has been effective in strengthening collaboration between cluster

schools. Some cluster leads who commented that there was strong collaborative

cluster working before the Project reported improved collaboration. Effective

collaboration was evident from the planning stage; for example, once all the

headteachers in one cluster had agreed to apply for the grant funding, a smaller

cluster sub-group developed the submission. Occasionally cluster leads reported

38

that their collaborative working was strong prior to the Project and the Project had

not had any impact on this. A collaborative approach was undertaken to allocate the

supernumerary teachers’ timetables, and three quarters of the other cluster schools

responding to the survey agreed that the supernumerary teachers had been

deployed fairly, with the feedback they provided during cluster meetings informing

this. Having flexibility in the allocation of the supernumerary teachers was viewed

positively, with some clusters able to accommodate individual school requests to

alter when they received their share of the supernumerary teacher’s time.

5.19 Cluster leads and other cluster school headteachers reported that the clusters

discussed the management and delivery of the Project regularly and communication

between schools was effective. The frequency of meetings between cluster schools

varied widely, with some arranging meetings every half term and others meeting

termly. In some cases, the Project was an agenda item on monthly cluster

meetings. One cluster lead commented that even though they work with other

schools ‘unless you have a specific reason to meet, sometimes you can go weeks

without meeting and this [the Project] has almost created an official calendar that

we have to meet as we have to fulfil certain obligations and as a result other things

are added to the agenda and discussed’.

5.20 Some cluster leads reported that cluster schools shared effective management

approaches and tools throughout the Project. For example, an online calendar was

used to oversee the allocation of the supernumerary teachers, with the calendar

easy for the supernumerary teachers and the different schools to access, the cluster

discussed in Case study 1 used this tool effectively. This approach also meant that

supernumerary teachers had access to their timetable in advance. Having a single

member of staff, usually at the cluster lead school, as the main point of contact for

supernumerary teachers was also effective and ensured clear communication. The

approach used to share information online during the Project has been used to

share other collaborative documents within one cluster. For example, School

Development Plans, and the Cluster Improvement Plan was developed

collaboratively using the same online platform.

39

5.21 Supernumerary teachers shared teaching and learning approaches between cluster

schools. The sharing of practice and ideas, such as approaches to the new

curriculum, behaviour management strategies, approaches to support learners or

specific curriculum delivery ideas were viewed by headteachers as positive

outcomes to emerge from the Project. One cluster school headteacher commented

that the supernumerary had taken ‘best practice and strategies back to the other

school and added value to them’.

Sharing effective practice

One cluster lead commented on an example where the supernumerary teacher

observed a child struggling to build sentences independently. The teacher

recalled seeing a programme delivered at one of the other cluster schools on

building sentences in a systematic way; this was then used to support the child.

It proved successful, and the child is continuing to use the programme. (Cluster

lead)

5.22 Successful collaborative cluster school projects were completed during the Project.

Cluster projects have been directly supported by supernumerary teachers delivering

activities across cluster schools, or by the supernumerary teachers providing the

cover of lessons needed for other teachers to complete such activities, attend

meetings or training in order to progress a cluster project. Examples of such

projects include:

Areas of Learning and Experience meetings to inform the development of the

new curriculum.

Humanities – main class teachers taught alongside the supernumerary teachers

for a term, also providing the opportunity to withdraw small groups of learners to

focus on specific elements of the project.

Maths curriculum development – all supernumerary teachers attended training

and have had input across all cluster schools into the development of a

consistent maths curriculum across one cluster

More Able and Talented training

Restorative Justice training

40

Shared attendance officer

Shared Welsh teacher

Sharing behaviour and learning management approaches across phases

resulted in a better understanding of the approaches for one cluster

STEM – the supernumerary teachers assisted class teachers to deliver a half

term project, which culminated in a presentation attended by all the cluster

schools

5.23 Activities initiated by the Project have helped ensure that collaborative working is

becoming an increasingly integrated part of how schools plan and deliver,

supporting wider school-to-school working. Teachers have had the time to lead on

developments and take on ownership and responsibility. However, one

supernumerary teacher’s poor attendance record limited the progress one cluster

was able to make against the cluster’s objectives.

5.24 The Project has had a positive impact on transition processes for schools and

learners. The Project has enabled collaboration between schools that has

supported schools’ transition activities. Supernumerary teachers working across

phases were able to develop longer term relationships with year 6 learners and the

‘familiar face’, and consistency in approach to behaviour and learning supported

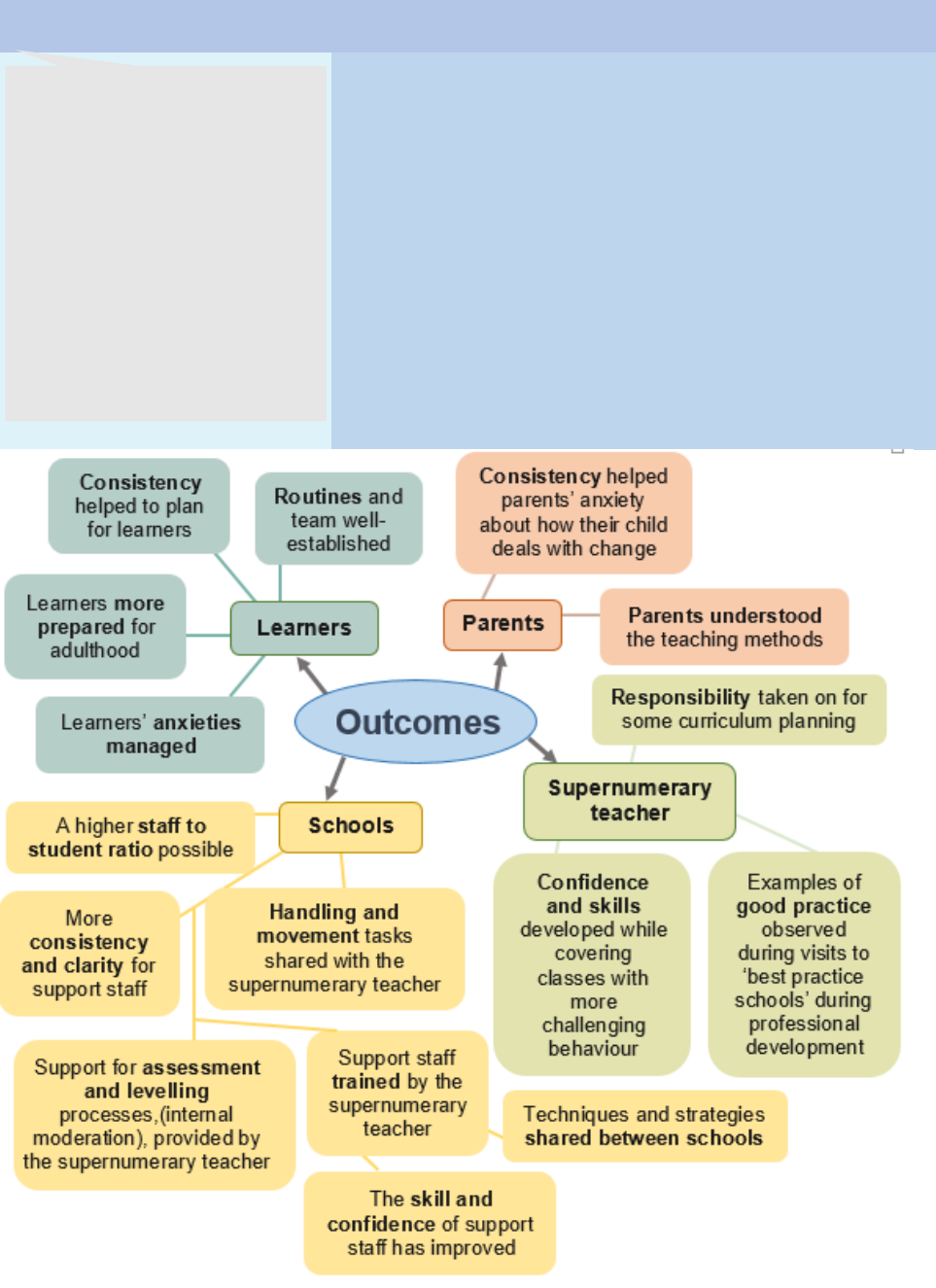

effective transition to the secondary phase. A couple of clusters reported specific