https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508417691019

Assessment for Effective Intervention

2017, Vol. 43(1) 34 –47

© Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2017

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1534508417691019

aei.sagepub.com

Special Series Article

Over the course of the last decade, increased importance

has been placed on schools’ ability to improve the behav-

ioral outcomes of their students. In an effort to support stu-

dent behavior, many schools have chosen to implement

multitiered systems of support (MTSS). Within an MTSS

framework, evidence-based interventions are delivered

with fidelity at each of three tiers, or specified levels of

need (Gresham, 2011). Although the implementation of

evidence-based interventions is a critical component of sup-

porting student behavior, it is equally important to be able

to measure whether a student’s behavior is improving as a

result of the intervention. Thus, to implement an MTSS

framework successfully, it is critical to reliably and validly

assess a student’s response to an intervention.

To reliably and validly assess response to intervention, it

is necessary that there be readily available tools, or forma-

tive assessment measures, that have the capacity to monitor

real-time changes student behavior over a relatively short

period of time. Through the efficient and effective use of

reliable formative assessment tools, schools are able to

engage in a valid, data-based decision-making process

about the effectiveness of interventions. In turn, schools can

appropriately identify the supports that a child needs to

achieve behavioral success. To this extent, this study evalu-

ates the capacity of Direct Behavior Rating–Single Item

Scales (DBR-SIS) to monitor student response to a Daily

Report Card (DRC) intervention. In addition, this study

investigates the relationship between the method of assess-

ment utilized (i.e., DBR-SIS or Systematic Direct

Observation [SDO]) and the decisions made about student

response to supports.

Formative Assessment in MTSS

Given that the link between reliable assessment and valid

decision making is central to an MTSS framework and evi-

dence-based practice, it is somewhat surprising that more

attention has not been given to the establishment of tools to

measure the response to those interventions. As a result,

school personnel have often relied on developing and utiliz-

ing their own behavioral assessment tools on a case-by-case

basis to meet progress-monitoring needs. For example,

691019AEI

XXX10.1177/1534508417691019Assessment for Effective InterventionMiller et al.

research-article2017

1

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA

2

University of Connecticut, Storrs, USA

Corresponding Author:

Faith G. Miller, Department of Educational Psychology, University of

Minnesota, 250 Education Sciences Building, Minneapolis, MN 55455,

USA.

Email: [email protected]

Progress Monitoring the Effects of Daily

Report Cards Across Elementary and

Secondary Settings Using Direct Behavior

Rating: Single Item Scales

Faith G. Miller, PhD

1

, Nicholas J. Crovello, MA

2

, and Sandra M. Chafouleas, PhD

2

Abstract

Direct Behavior Rating–Single Item Scales (DBR-SIS) have been advanced as a promising, systematic, behavioral, progress-

monitoring method that is flexible, efficient, and defensible. This study aimed to extend existing literature on the use of

DBR-SIS in elementary and secondary settings, and to examine methods of monitoring student progress in response to

intervention. To this end, two concurrent multiple baseline design studies were conducted in a diverse magnet school

district located in the northeastern United States. One study was conducted with four students in kindergarten and first

grade, whereas the second study was conducted with three students in 10th and 11th grade. Response to a Daily Report

Card (DRC) intervention was monitored using two different approaches: DBR-SIS and systematic direct observation

(SDO) probes. Across all participants, modest improvements in behavior were observed using both visual and quantitative

analyses of DBR-SIS data; however, decisions regarding student response to the intervention varied as a function of the

dependent variable analyzed. Implications for practice and future directions for research are discussed.

Keywords

high school, elementary, progress monitoring

Miller et al. 35

common approaches to progress monitoring may include

various types of behavioral point sheets, behavior contracts,

or DRCs. These tools often lack information regarding their

technical adequacy, and thus may lead to inappropriate

decisions regarding student supports. According to

Chafouleas, Riley-Tillman, and Christ (2009), any tool

intended for use within a problem-solving MTSS frame-

work must be flexible, defensible, efficient, and repeatable.

That is, the instrument should be able to reliably and validly

measure student response to an intervention with relative

ease on multiple occasions and in multiple settings.

SDO

Given the need for defensible formative assessment meth-

ods, school psychologists have often turned to the use of

SDO. The strengths of SDO have been often cited in the

literature (Hintze, Volpe, & Shapiro, 2002). However,

trained observers using SDO require three to five observa-

tions to generate a single reliable estimate of student aca-

demic engagement (Briesch, Chafouleas, & Riley-Tillman,

2010). Thus, if a school psychologist wished to obtain five

reliable data points to assess the trend of academic engage-

ment, it would be necessary to collect data on 15 to 25 occa-

sions. As a considerable amount of data points are needed to

reliably assess behavior over time, it is worth noting that

SDO requires a substantial amount of resources to be used

effectively. Most notably, SDO relies on the presence of

external observers in the classroom whose sole focus is to

assess the behavior of a given student. Therefore, the use of

SDO as the primary formative assessment measure would

require an external observer to be present in the classroom

rather frequently. Although this may be possible or even

desirable in high stakes situations, the use of SDO to moni-

tor response to intervention for all students receiving some

type of support is not feasible. Therefore, although the use

of SDO can result in psychometrically defensible data,

schools may not be able to allocate the resources required to

generate the necessary number of data points to effectively

determine the response to an intervention for every student

that may be receiving some type of individualized behav-

ioral support.

Direct Behavior Rating

To address some of the limitations inherent to the use of

SDO, researchers have attempted to establish an assessment

method that meets all four key criteria outlined by Chafouleas

and colleagues (2009) as required of a formative assessment

measure within a problem-solving MTSS framework (flexi-

ble, defensible, repeatable, and efficient). The product of this

work is an assessment method known as Direct Behavior

Rating (DBR). DBR can be best described as a hybrid

assessment tool that combines elements of a rating scale and

SDO (Chafouleas, 2011). In using DBR, a user makes an

evaluation of a specific behavior at the time and place that

the behavior occurs (Chafouleas et al., 2009). A unique

advantage of DBR is that teachers or other individuals that

are inherent to the classroom setting (e.g., paraprofessional)

serve as the typical raters, and they are typically able to com-

plete the measure in less than 1 min per day. Given this rela-

tive ease of use, DBR allows more frequent assessment (e.g.,

daily) over an extended period of time.

DRC as an Assessment Tool

Within the broad assessment domain of DBR, a DRC is

viewed as a specific application often implemented as part

of an intervention package (Chafouleas, 2011; Chafouleas

et al., 2009). Although DRCs have traditionally been used

to support home–school communication, they are not with-

out utility as an assessment instrument (Chafouleas, Riley-

Tillman, & McDougal, 2002). In fact, the capacity to serve

as a progress-monitoring tool has been highlighted as an

attractive quality of DRCs, as one study has shown a mod-

erate association between DRC and SDO data (Chafouleas,

McDougal, Riley-Tillman, Panahon, & Hilt, 2005). There

are, however, some significant limitations on the use of

DRC as a formative assessment measure. Primarily,

researchers have noted that user-developed tools such as

DRCs may not have psychometric evidence to support use

or may not be constructed to be adequately sensitive to

detect behavior change (e.g., Miller, Patwa, & Chafouleas,

2014; Venn, 2012). That is, the defensibility of this approach

may be ambiguous compared with more standardized

assessment approaches. Similarly, if the scale construction

of the DRC were qualitative in nature (as may be used for

younger students), another data source may be required for

quantitative progress monitoring. Furthermore, the DRC

would be limited in monitoring general outcome behaviors

(e.g., academic engagement, disruptive behavior) if the

intervention targeted a more specific behavior (e.g., fre-

quency of hand raises). Taken together, the limitations on

the use of a DRC as a formative assessment measure likely

require the use of an additional measure to ensure reliable

and valid progress monitoring.

DBR-SIS

A majority of the research on DBR has centered on the evalu-

ation of DBR-SIS, which focus on the assessment of three core

behavioral competencies (academically engaged [AE], disrup-

tive [DB], and respectful) as occurring over the duration of an

observation period (Chafouleas, 2011; Volpe & Briesch, 2012).

DBR-SIS was developed as a systematic and standardized

approach to formative assessment of student behavior (Miller,

Riley-Tillman, Chafouleas, & Schardt, 2017). A programmatic

line of research has emerged regarding the evaluation of the

36 Assessment for Effective Intervention 43(1)

technical adequacy of DBR-SIS. Results from a series of gen-

eralizability analyses have demonstrated that data generated

from DBR-SIS can reach adequate levels of reliability when a

single rater (i.e., the same teacher) completes DBR-SIS across

several occasions (Chafouleas et al., 2010; Chafouleas, Christ,

Riley-Tillman, Briesch, & Chanese, 2007; Christ, Riley-

Tillman, Chafouleas, & Boice, 2010). Although Chafouleas

and colleagues (2010) suggested that up to 10 to 20 observa-

tions might be needed to achieve a single reliable estimate of

student academic engagement, this recommendation is less

burdensome given the efficiency of DBR-SIS data collection

(i.e., one observation requires only 1 min to collect). Thus, a

user of DBR-SIS requires 20 min to generate a reliable esti-

mate of academic engagement (20 observations × 1 min),

which is substantially less than the 45 to 75 min required when

using SDO (three to five observations × 15 min).

In addition to establishing the capacity for DBR-SIS to

produce reliable data, use in progress-monitoring assess-

ment must also be validated by assessing an instrument’s

ability to detect behavioral change. To this extent, Fuchs

(2004) proposed that researchers evaluate an instrument’s

technical features of level and trend. In other words, eval-

uating an instrument’s technical features of level and trend

is akin to evaluating how much and how quickly that

instrument can detect behavioral change (Chafouleas,

Sanetti, Kilgus, & Maggin, 2012). In one study that evalu-

ated the sensitivity of DBR-SIS to behavioral change,

Chafouleas and colleagues (2012) found that DBR-SIS

demonstrated adequate ability to detect changes in behav-

ior regardless of the change metric that was analyzed (e.g.,

absolute change, percent of nonoverlapping data points,

effect size, etc.).

The Relationship Between DBR-SIS

and SDO

Although DBR-SIS has demonstrated the ability to generate

psychometrically defensible data as well as the ability to

detect behavioral change, it is logical to explore its corre-

spondence with SDO in evaluating response to intervention.

Early investigations into the correspondence between DBR

and SDO revealed that both data sources were generally

consistent in their evaluation of both individual (Chafouleas,

Riley-Tillman, Sassu, LaFrance, & Patwa, 2007) and class-

wide (Riley-Tillman, Methe, & Weegar, 2009) social behav-

iors, including the suggestion of a functional relationship

upon visual analysis. Although correspondence between

DBR and SDO has been found, it is important to note that

correspondence does not necessarily imply perfect agree-

ment, thereby suggesting some moderate differences in the

dependent variable dependent on the data source utilized

(Riley-Tillman, Chafouleas, Sassu, Chanese, & Glazer,

2008). Relatedly, more recent investigations have shown a

greater correlation between DBR-SIS and SDO for off-task

behaviors, whereas the correspondence is attenuated for on-

task behaviors (Chafouleas et al., 2012).

DRC as an Evidence-Based

Intervention

In addition to an assessment option, DRCs have been estab-

lished as a flexible, efficient, and effective intervention

method for both increasing on-task behavior and decreasing

DB (Chafouleas et al., 2002; Vannest, Davis, Davis, Mason,

& Burke, 2010; Volpe & Fabiano, 2013). Although the

structure and format of the intervention can vary, it typi-

cally includes a system of daily behavior monitoring, fre-

quent teacher feedback, and the delivery of a reward

contingent on meeting a specified behavior goal (Vannest

et al., 2010; Volpe & Fabiano, 2013). DRCs have been

found to be an effective intervention across a wide range of

demographic variables (e.g., race, age, etc.; Vannest et al.,

2010). Given the noted effectiveness of a DRC intervention,

as well its general acceptability and frequent use (Chafouleas

et al., 2007), it was a logical choice to evaluate the capacity

of DBR-SIS to monitor student response to intervention.

Purpose

Implementing evidence-based interventions and evaluating

students’ subsequent response to the interventions at fre-

quent, repeated intervals are the cornerstone components to

the successful implementation of an MTSS model. Yet, it is

clear that substantial gaps in the literature limit the ideal

implementation of the MTSS framework. Thus, it is neces-

sary that there be increased understanding of different for-

mative assessment measures and the implications for

data-based decision making that are associated with using a

particular method. Although user-created measures (such as

intervention outcome data) may present a readily available

data source, the psychometric defensibility required for

valid decision making or capacity for consistent monitoring

of general outcome behaviors is questionable. Although

SDO addresses these limitations, the method does so at the

cost of devoting a substantial amount of resources needed to

assess behavior repeatedly over time. To this extent, DBR-

SIS offers an option that capitalizes on the strengths of both

DRC and SDO.

Although support exists for the use of DBR-SIS in prog-

ress monitoring, the literature has indicated that the measure

does not perfectly align with SDO. As the ultimate purpose

of assessment is to engage in data-based decision making

about student supports, it is logical to ask whether this non-

conformity between data sources would lead to different

decisions about student supports. In other words, the litera-

ture has not yet explored whether or not there would be dif-

ferences in the decisions made about the effectiveness of the

intervention dependent on the data source that was utilized.

Miller et al. 37

Taken together, further investigation is necessary to (a)

add support to the growing body of evidence regarding the

validity of DBR-SIS as a formative assessment instrument

within an MTSS framework and (b) evaluate potential dif-

ferences in the conclusions made about intervention effec-

tiveness based on outcome data from DBR-SIS and SDO,

respectively. To this extent, this study utilized DBR-SIS and

SDO to monitor student response to a DRC intervention

implemented within a multiple baseline design framework

in a diverse magnet district in the northeastern United

States. Research questions and associated hypotheses were

posed as follows:

Research Question 1: Does DBR-SIS demonstrate ade-

quate sensitivity as a formative assessment measure?

Hypothesis 1: DBR-SIS will demonstrate adequate sen-

sitivity to detecting behavioral change in response to a

DRC intervention.

Research Question 2: Do data obtained from DBR-SIS

and SDO suggest similar or different interpretations

about the students’ responses to the intervention?

Hypothesis 2: Different data sources will lead to differ-

ent conclusions and decisions regarding students’

response to intervention.

General Method

Data were collected during the 2013–2014 school year in

large urban regional magnet school district located within

the Northeastern United States. Two separate studies were

conducted, one in an elementary setting and one in a sec-

ondary setting. Subsequent to securing administrator sup-

port, teachers attended an informational session describing

the study purpose and procedures. During the informational

session, a research assistant described the target population

of interest and inclusion criteria (i.e., students with chal-

lenging behavior who did not have major external contribu-

tors to behavior such as chronic absenteeism or inconsistent

medication, and were not identified with a disability).

Teachers who were interested in participating then con-

tacted the research assistant and (a) provided consent to par-

ticipate, (b) were asked to identify a student they worked

with whom met inclusion criteria, and (c) made contact

with the student’s parent/guardian to determine interest in

participating in the study. Parental consent and student

assent were obtained for all participants, and all study pro-

cedures were approved by the university’s human-subjects

internal review board. Pseudonyms were used to protect

participant confidentiality.

Measures

DBR-SIS. DBR-SIS reflects the rater’s perception of the pro-

portion of time a student is observed to be engaged in a

target behavior on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 10

(always). Target behaviors were selected in consultation

with the teacher, and one of two behaviors were selected for

progress monitoring: AE or DB based on teacher preference

and perceived student need. Definitions and examples of

each target behavior were provided on the top of the DBR-

SIS form. AE behavior was defined as actively or passively

participating in classroom activities. DB was defined as stu-

dent action that interrupts regular school or classroom

activities. Students were rated during the target activity that

was deemed most problematic by the teacher.

SDO. External observers completed 15-min observations of

target students using a momentary time sampling (MTS)

recording procedure with 10-s intervals. This recording pro-

cedure was selected as MTS procedures have been found to

produce accurate estimates of the duration of a target behav-

ior (Suen, Ary, & Covalt, 1991).

Target behaviors that were selected for progress moni-

toring using DBR-SIS were also used for SDO (i.e., the

same behavior and definition was utilized for both DBR-

SIS and SDO). Observations were conducted approximately

once per week. Consistent with What Works Clearinghouse

design standards, interobserver agreement (IOA) data were

collected on at least 20% of observations per phase, with a

goal of at least 80% agreement (Kratochwill et al., 2010).

For Study 1, IOA data were collected for 33% of baseline

phase data points and 29% of intervention phase data points.

For Study 2, IOA data were collected for 42% of baseline

phase data points and 52% of intervention phase data points.

Across studies, IOA ranged from 92% to 100%, with an

average of 98%.

Usage Rating Profile–Intervention Revised (URP-IR). To evalu-

ate teacher perceptions of the DRC, the URP-IR was used to

collect information regarding the social validity of the inter-

vention. The URP-IR is a self-report measure that consists of

29 items to which participants respond regarding their level

of agreement to statements provided using a 6-point Likert-

type scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Prior research on the URP-IR has supported a measure with

six factors that include Acceptability, Understanding, Feasi-

bility, Home–School Collaboration, System Climate, and

System Support (Briesch, Chafouleas, Neugebauer, & Riley-

Tillman, 2013). The Acceptability factor incorporates items

related to the appropriateness of the intervention and the

respondent’s interest and enthusiasm in using the interven-

tion. The Understanding factor incorporates items related to

respondent’s knowledge regarding the intervention and

associated procedures in using it. The Home–School Col-

laboration factor includes items evaluating the extent to

which respondents feel this collaboration is necessary in

supporting use of the intervention. The Feasibility factor

includes items related to ease of use. The System Climate

38 Assessment for Effective Intervention 43(1)

factor includes items evaluating the compatibility of the

intervention with the school environment. Finally, the Sys-

tem Support factor includes items evaluating the extent to

which respondents feel additional support is needed to carry

out the intervention.

Procedures

Participating teachers engaged in a structured behavioral con-

sultation process including four stages: problem identifica-

tion, problem analysis, treatment implementation, and

treatment analysis. At each stage, a research assistant served

as a consultant and conducted an interview to inform the

development and implementation of the DRC, including (a)

defining individual target behaviors (b) setting goals and

establishing reward contingencies to be delivered in the school

setting, and (c) setting up a home–school communication sys-

tem where the DRCs would be signed by parents/guardians

and returned the following day. Each DRC was created in an

effort to be developmentally appropriate to the target student,

such that a simple Yes/No scale was used for students in kin-

dergarten and first grade, and a continuous scale (0–10) was

used for secondary students. At the end of the target activity,

the teacher and student reviewed the DRC together and agreed

upon ratings. Reinforcers were identified through a reward

menu that was developed in discussion between the teacher

and the student, and individual criteria were set for access to

reinforcement based on that discussion. Research assistants

and participating teachers followed a structured training pro-

tocol for introducing the DRC intervention to participating

students. The training included (a) describing the purpose of

the intervention, (b) providing examples and nonexamples of

the DRC target behaviors, (c) a discussion of how to assign

ratings on the DRC, and (d) a discussion of specific goals and

rewards to be delivered contingent upon goal attainment. At

the start of the study, participating teachers were trained in

data collection procedures and completed an online training

module on DBR-SIS. DBR-SIS ratings served as the primary

outcome measure, supplemented with periodic SDO observa-

tions. To facilitate comparison between data sources, DBR-

SIS data were converted from a 0–10 scale to a 0–100 scale.

For both studies, a concurrent multiple baseline design across

participants was used to evaluate student response to the inter-

vention. Students were randomly assigned to the order in

which the intervention would begin, and the study design was

aligned to What Works Clearinghouse single-case design

standards (Kratochwill et al., 2010).

Data Analyses

Both visual and quantitative analyses were conducted to

evaluate student response to the DRC intervention.

Specifically, we examined DBR-SIS ratings for documenta-

tion of an experimental effect through visual evaluation of

change in (a) level, (b) trend, (c) variability, (d) degree of

overlap, and (e) immediacy of effect (Kratochwill et al.,

2010). To quantitatively evaluate student response to inter-

vention, either Tau-U or Tau

novlap

effect size (ES) metrics

were used, depending on the nature of the data. Tau-U and

Tau

novlap

were described by Parker, Vannest, Davis, and

Sauber (2011), with Tau-U accounting for positive baseline

trend when statistically significant trend is observed. These

metrics are interpreted as the percentage of pairwise data,

which shows improvement across phases in a time-forward

direction and is calculated by subtracting the percentage of

pairwise overlap from the percentage of pairwise nonoverlap.

A web-based calculator developed by Vannest, Parker, and

Gonen (2011) was used in all ES calculations. A threshold

alpha value of .05 was used in all significance tests.

Study 1

Participants and Setting

Participating students were enrolled in a regional magnet

elementary school serving approximately 400 students

(K-5). Approximately 35% of students enrolled at the

school qualified for free or reduced lunch. The school

served a diverse student body; 36% of the students identi-

fied as White, 25% identified as Hispanic, and 24% identi-

fied as Black, 10% as Asian or Asian/Pacific Islander, and

5% as multiracial.

A total of four students participated in Study 1, all of

whom attended general education classrooms and were not

identified with a disability. All of the students were in kin-

dergarten or first grade, and were selected by their teachers

due to problematic behavior in the classroom. Two of the

students, Jordan and Amari, received supplemental sup-

ports for behavior.

Jordan. Jordan was a 5-year, 5-month old, male, Black,

Non-Hispanic student in kindergarten. Jordan received

small group reading support, and also took frequent breaks

with a behavior specialist. Prior to starting the intervention,

Jordan accumulated 37 office discipline referrals (ODRs)

during the 2013–2014 school year due to defiance, disre-

spect, noncompliance, DB, physical aggression, property

damage, and leaving the instructional area. Jordan received

pull-out support from a behavior specialist when his behav-

ior became too challenging for his teacher to manage

independently.

Jordan’s teacher, Ms. A., identified reading as his most

problematic activity during the school day. Specifically,

Jordan had difficulty transitioning to reading (cleaning up

prior activities and sitting in his designated spot).

Furthermore, during reading instruction, he would not sit

quietly and listen, and also would not participate in discus-

sions. Ms. A. reported that this problematic time seemed to

Miller et al. 39

set the stage for difficulties throughout the school day.

Consequently, Jordan’s DRC comprised the following

goals: (a) Was I ready for reading (cleaned up activity, went

to carpet, with less than three reminders)? (b) Did I sit qui-

etly and listen to my teacher? (c) Did I participate? Given

that previous intervention efforts focused on Jordan’s nega-

tive behaviors had been unsuccessful, Ms. A. expressed that

she wanted to target a positive behavior for the purpose of

this study. In line with these goals, Jordan’s progress was

monitored using the AE scale on the DBR-SIS form. Jordan

received a small reward for meeting two of the three goals

and a large reward for meeting all three goals.

Kai. Kai was a 5-year-8-month-old, male, Black, Non-His-

panic student in kindergarten. Kai received small group

reading support, but did not receive any supplemental

behavior supports. Kai had accumulated 66 ODRs prior to

starting intervention in the 2013–2014 school year due to

due to defiance, disrespect, and noncompliance.

Kai’s teacher, Ms. B., identified morning meeting time

as most problematic. Specifically, Kai would not follow

teacher directions, use his quiet voice, or stay in his own

space. Consequently, Kai’s DRC comprised the following

goals: (a) Did I follow teacher directions? (b) Did I use my

quiet voice? (c) Did I stay in my own space? She reported

frustration with the frequency with which Kai was referred

to the office, and that this prior focus on negative behaviors

had been unsuccessful. Consequently, Ms. A. expressed that

she wanted to target a positive behavior for the purpose of

this study. Kai received a small reward for meeting two of

the three goals and a large reward for meeting all three

goals. In line with these goals, Kai’s progress was moni-

tored using the AE scale on the DBR-SIS form.

Preston. Preston was a 6-year-11-month-old, male, White,

Non-Hispanic, first-grade student. He did not receive any

supplemental supports. Prior to receiving intervention,

Preston accrued 16 ODRs in the 2013–2014 school year due

to due to defiance, disrespect, noncompliance, physical

aggression, and DB.

Preston’s teacher, Ms. C., identified reading as his most

problematic activity during the school day. In particular, he

had difficulty following directions, being kind to his peers,

and managing frustration appropriately. Consequently,

Preston’s DRC comprised the following goals: (a) Did I fol-

low teacher directions? (b) Was I kind to my peers? (c) Did

I handle my frustration in a responsible way? Preston

received a small reward for meeting two of the three goals

and a large reward for meeting all three goals. In line with

these goals, Preston’s progress was monitored using the DB

scale on the DBR-SIS form.

Amari. Amari was a 6-year-4-month-old male, Black, Non-

Hispanic first-grade student. He received small group

pull-out support in reading, and also saw the school social

worker for individualized behavioral support. Amari

accrued 48 ODRs in the 2013–2014 school year prior to

starting the intervention due to defiance, disrespect, non-

compliance, harassment/bullying, DB, physical aggression,

property damage, and inappropriate language

Amari’s teacher, Ms. D., identified writing time as most

problematic and wanted to target staying seated, initiating

writing tasks, and completing writing prompts. She identified

academic engagement as the primary outcome of interest for

Amari. Consequently, Amari’s DRC comprised the following

goals: (a) Did I sit in my seat for the first 10 min of writing

time? (b) Did I start my writing work? (c) Did I write on at

least three pages? Amari received a small reward for meeting

two of the three goals and a large reward for meeting all three

goals. In line with these goals, Amari’s progress was moni-

tored using the AE scale on the DBR-SIS form.

Results

Results of the study are displayed in Figure 1. Examination

of DBR-SIS baseline data across participants revealed con-

siderable variability as opposed to stability of data, thus

decision rules were developed for determining when to ini-

tiate the intervention: (a) The last 3 data points were rela-

tively stable, defined as within a range of 10% of each other

or (b) a trend was observed in the direction opposite of the

intended effect. Jordan, Kai, and Preston met the first deci-

sion rule of relative stability, whereas Amari met the second

decision rule of trend observed in the direction opposite of

the intended effect.

Across participants, evidence is provided regarding the

immediacy of effect, thus suggesting a functional relation-

ship between the introduction of the intervention and

improvements in student behavior according to visual analy-

sis of DBR-SIS data. Improvements were also observed in

regard to the level of student behavior, with mean levels of

AE increasing from baseline to intervention and mean levels

of DB decreasing from baseline to intervention (see Table 1).

With regard to trend, improvements were observed for Jordan

and Preston; Kai and Amari both exhibited a slightly increas-

ing trend during baseline that continued during intervention.

Notably, the behavior exhibited across students was

highly variable, and consequently, there were a fairly large

number of overlapping data points between baseline and

intervention phases across all students. Thus, quantitative

effect size metrics were used to supplement visual analyses.

The Tau

novlap

effect size metric described by Parker, Vannest,

Davis, and Sauber (2011) was used, which is similar to

Tau-U but does not account for baseline trend. None of the

participants exhibited statistically significant baseline trend

(p > .05), thus, Tau

novlap

was deemed appropriate. Phase

contrasts were performed between the baseline and inter-

vention conditions, and DBR-SIS data were analyzed to

40 Assessment for Effective Intervention 43(1)

Figure 1. Elementary DBR-SIS data (Study 1).

Note. DBR-SIS = Direct Behavior Rating–Single Item Scales.

Miller et al. 41

determine (a) the magnitude of effects and (b) whether sta-

tistically significant improvement in behavior were

obtained. Individually, the largest effect size was obtained

for Jordan (Tau

novlap

= .64, p < .001), followed by Amari

(Tau

novlap

= .51, p = .01), while smaller, nonstatistically sig-

nificant effects were observed for Kai (Tau

novlap

= .31, p >

.05) and Preston (Tau

novlap

= −.30, p > .05). When combined

across all students, the omnibus effect size estimate sug-

gested that statistically significant improvements in behav-

ior were obtained overall (Tau

novlap

= .44, p < .01).

DBR-SIS and SDO. To facilitate comparison between data

sources, DBR-SIS data were converted from a 0–10 scale to

a 0–100 scale. Both DBR-SIS and the SDO procedures uti-

lized in this study were designed to provide estimates

regarding the duration of the target behavior during the

intervention period. As shown in Table 1, differences were

observed between DBR-SIS and SDO in regard to estimates

of duration. In particular, estimates of duration tended to be

slightly higher using DBR-SIS compared with SDO, with

the exception of Jordan. However, both data sources sug-

gested improvements in student behavior from the baseline

phase to the intervention phase. Effect size estimates were

slightly different between DBR-SIS and SDO, with statisti-

cally significant effects obtained for Amari based on DBR-

SIS data but not SDO data.

Treatment integrity and social validity data. Treatment integrity

was investigated by examining permanent products collected

throughout the intervention period, including daily DBR-SIS

rating forms and DRCs for each student–teacher dyad.

Although missed days of implementation occurred due to

teacher or student absences, field trips, and state testing, of the

eligible implementation days during the study, Jordan’s DRC

was implemented 98% of eligible intervention days, whereas

Amari’s DRC was implemented 90%, Kai’s DRC was imple-

mented 80%, and Preston’s DRC was implemented 77%.

Social validity data collected using the URP-IR indicated that

all four teachers rated the DRC intervention favorably (ratings

of 4 or greater) on the following subscales: Acceptability,

Understanding, Feasibility, and System Climate. Mixed rat-

ings were provided in terms of Home–School Collaboration

and System Support, with some teachers rating these sub-

scales high and others rating these subscales low (see Table 3).

Study 2

Participants and Setting

For Study 2, participating students were enrolled in a

regional magnet secondary school serving approximately

350 students in Grades 6–12. Approximately 58% of the

student population qualified for free or reduced lunch. The

school served a diverse student body; 34% of the students

identified as Black, 30% identified as Hispanic, 24% identi-

fied as White, 8% as Asian or Asian/Pacific Islander, and

3% as multiracial.

In total, three students participated, all of whom attended

general education classrooms and were not designated with

a disability. All of the students were in high school (Grades

10 or 11), and their target classes were scheduled to meet 3

days per week. None of the students received supplemental

behavioral supports, nor were ever suspended or expelled.

All participating secondary teachers expressed that their

primary goal involved improving student learning via

enhanced student engagement.

Maya. Maya was a 16-year-old female, Black, Non-His-

panic 11th-grade student. Prior to participating in the study,

Maya accumulated 14 ODRs in the 2013–2014 school year

Table 1. Comparison of Progress-Monitoring Data From Study 1 (Elementary).

Pseudonym

DBR-AE

M (SD)

DBR-DB

M (SD)

SDO-AE

M (SD)

SDO-DB

M (SD)

Tau

novlap

DBR-SIS

Tau

novlap

SDO

Jordan

Baseline 16% (18) 47% (14) 0.64* 0.84*

Intervention 48% (29) 75% (15)

Kai

Baseline 77% (15) 67% (10) 0.31 0.43

Intervention 84% (14) 79% (16)

Preston

Baseline 43% (33) 12% (15) −0.3 −0.27

Intervention 26% (25) 6% (11)

Amari

Baseline 42% (22) 38% (26) 0.51* 0.6

Intervention 61% (22) 61% (16)

Note. DBR = Direct Behavior Rating; AE = academically engaged; DB = disruptive behavior; SDO = systematic direct observation; SIS = Single Item

Scales.

*p < .05.

42 Assessment for Effective Intervention 43(1)

due to defiant and DB, being tardy to class, and for dress

code violations. Maya’s Chemistry teacher, Ms. F., partici-

pated in the study, and expressed that her primary goal was

to increase Maya’s AE behavior during class. Maya would

periodically put her head down on her desk and refuse to

participate. She also would not complete classwork or home-

work and was in danger of failing the class, despite having

average to above average academic skills. Mrs. F. expressed

that Maya would often argue with her, and preferred the use

of a simple dichotomous scale as opposed to a continuous

scale. Consequently, Maya’s DRC comprised the following

yes/no items: (a) Was I engaged for at least half of class? (b)

Did I complete all of my classwork? (c) Did I complete and

turn in all of my homework? Maya’s goal was to answer

“Yes” to either items A and B or A and C.

Alex. Alex was a 16-year-old male, Black, Non-Hispanic,

10th-grade student. Prior to participating in the study, Alex

accumulated nine ODRs in the 2013–2014 school year for

DB, being tardy to class, and dress code violations. Alex’s

Math teacher, Ms. G., participated in the study, and her pri-

mary goal was to increase Alex’s AE behavior during class.

Consequently, Alex’s DRC comprised the following items,

where Alex rated himself on a 0 to 10 scale, ranging from

not at all to always: (a) How engaged was I during class

activities (goal: rating of 7 or higher)? (b) How well did I do

with classwork completion (goal: rating of 7 or higher)? (c)

How often did I have off topic conversations (goal: 3 or

lower)? In line with these goals, Alex’s progress was moni-

tored using the AE scale on the DBR-SIS form.

Kayla. Kayla was a 16-year-old female, Black, Non-His-

panic 10th-grade student. Prior to participating in the study,

Kayla accumulated 10 ODRs in the 2013–2014 school year

for DB, being tardy to class, and for dress code violations.

Kayla’s Medical Sciences teacher, Ms., H., participated in

the study, and her primary goal was to increase Kayla’s AE

behavior during class. Consequently, Kayla’s DRC com-

prised the following items, where Kayla rated herself on a 0

to 10 scale, ranging from not at all to always: (a) How

engaged was I during class activities (goal of 7 or greater)?

(b) How often did I have off topic conversations (goal of 3

or lower)? (c) Did I come to class prepared (goal of Yes)? In

line with these goals, Kayla’s progress was monitored using

the AE scale on the DBR-SIS form.

Results

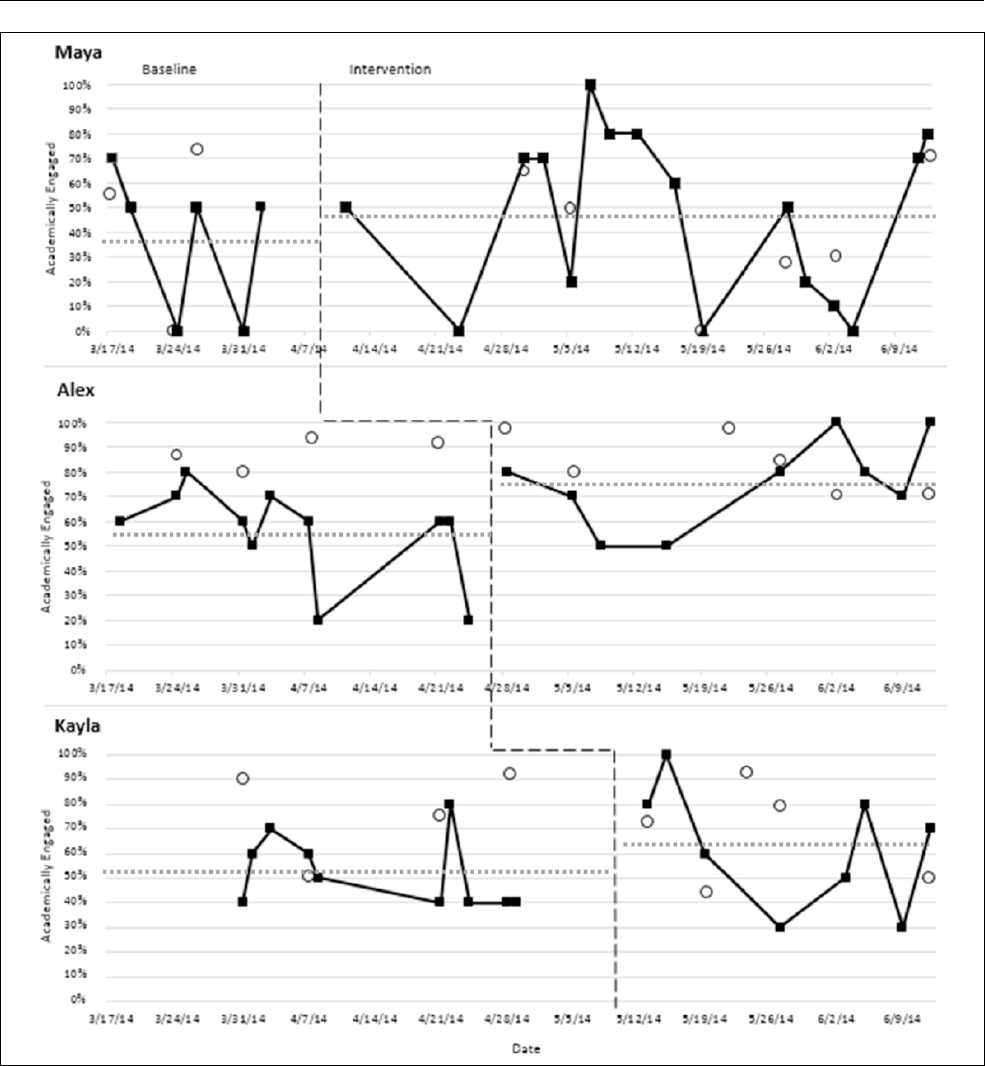

Results of the study are displayed in Figure 2. Examination

of DBR-SIS baseline data across participants revealed con-

siderable variability as opposed to stability of data, thus

decision rules were developed for determining when to ini-

tiate the intervention: (a) a predictable pattern of behavior

was established (Maya), (b) a trend was observed in the

direction opposite of the intended effect (Alex), or (c) the

last 3 data points were relatively stable, defined as within a

range of 10% of each other (Kayla).

For Alex and Kayla, evidence is provided regarding the

immediacy of effect, thus suggesting a functional relation-

ship between the introduction of the intervention and

improvements in student behavior according to visual anal-

ysis of DBR-SIS data. For Maya, intervention effects were

observed more gradually. Improvements were also observed

in regard to the level of student behavior, with mean levels

of AE increasing from baseline to intervention (see Table

2). With regard to trend, all three students exhibited a

slightly decreasing trend in AE during baseline. During

intervention, improved trend was observed for Alex and

Maya, but not for Kayla.

Notably, the behavior exhibited across students was

highly variable, and there were a significant proportion of

overlapping data points across baseline and intervention

phases for all students. Thus, quantitative effect size met-

rics were used to supplement visual analyses. None of the

participants exhibited statistically significant baseline

trend, and thus, Tau

novlap

was deemed appropriate. Phase

contrasts were performed between the baseline and inter-

vention conditions, and DBR-SIS data were analyzed to

determine (a) the magnitude of effects and (b) whether sta-

tistically significant improvement in behavior were

obtained. Individually, the largest effect size was obtained

for Alex (Tau

novlap

= .55, p = .04), while smaller, nonsig-

nificant effects were obtained for Maya (Tau

novlap

= .28, p

> .05) and Kayla (Tau

novlap

= .25, p > .05). When combined

across all students, the omnibus effect size estimate sug-

gested that statistically significant improvements in

behavior were obtained overall (Tau

novlap

= .36, p = .02). It

should be noted that, for Maya, an unanticipated event

may have impacted outcomes. Specifically, Maya was told

by a school counselor on 5/19/14 that she would not be

graduating on time, and her teacher reported that Maya

became disengaged and unmotivated following that

incident.

DBR-SIS and SDO. To facilitate comparison between data

sources, DBR-SIS data were converted from a 0–10 scale to

a 0–100 scale. As shown in Table 2, differences were

observed between DBR-SIS and SDO in regard to estimates

of duration. In particular, estimates of duration tended to be

higher using SDO compared with DBR-SIS. Interestingly,

conflicting decisions could be made with regard to student

response to intervention depending on the data source

examined; DBR-SIS data suggested modest improvements

in student behavior, whereas SDO data suggested that AE

decreased between baseline and intervention phases. Con-

sequently, effect size estimates were markedly different

between DBR-SIS and SDO, with DBR-SIS indicating

modest improvements in student behavior and SDO indicat-

ing that behavior became worse during the intervention

phase.

Miller et al. 43

Treatment integrity and social validity data. Treatment integ-

rity was investigated by examining permanent products col-

lected throughout the intervention period, including daily

DBR-SIS rating forms and DRCs for each student–teacher

dyad. Although missed days of implementation occurred

due to teacher or student absences, field trips, and state test-

ing, of the eligible implementation days during the study,

Alex and Kayla’s DRCs were implemented 100% of eligi-

ble intervention days, whereas Maya’s was implemented

81%. Social validity data collected using the URP-IR

Figure 2. Secondary DBR-SIS data (Study 2).

Note. Open circles denote systematic direct observation probes. Square markers denote DBR-SIS data. Dotted line denotes mean DBR-SIS score per

phase. Triangle data point on 5/19 denotes when the student was told she would not be graduating on time. DBR-SIS = Direct Behavior Rating–Single

Item Scales.

44 Assessment for Effective Intervention 43(1)

indicated that all four teachers rated the DRC intervention

favorably (ratings of 4 or greater) on the following sub-

scales: Acceptability, Understanding, Feasibility, and Sys-

tem Climate. Mixed ratings were provided in terms of

Home–School Collaboration and System Support, with

some teachers rating these subscales high and others rating

these subscales low (see Table 3).

General Discussion

The aims of the present study were to (a) add to the research

base regarding the validity of DBR-SIS as a progress-mon-

itoring instrument within an MTSS framework, and (b)

evaluate how different data sources might lead to different

conclusions and determinations with regard to student

response to the intervention. To this end, this study evalu-

ated student response to DRCs within two multiple baseline

designs in a diverse magnet school district located in the

northeastern United States, wherein student response to the

intervention was monitored using both DBR-SIS and SDO.

With regard to each of the research questions posed, this

study yielded several interesting findings.

First, with regard to the sensitivity of DBR-SIS as a for-

mative assessment tool, visual analysis of DBR-SIS data sup-

ported the sensitivity of the measure in detecting changes in

student behavior. In six of the seven cases, DBR-SIS data

provided evidence for immediacy of effect upon implemen-

tation of the DRC. Furthermore, the variability of data

obtained suggested that DBR-SIS captures fluctuations in

behavior and does not appear to demonstrate floor or ceiling

effects. Visual and quantitative analyses of the DBR-SIS data

generally supported a modest relationship between initiation

of the intervention and improvements in student behavior.

That is, all students evidenced improved behavior from base-

line to intervention phases based on DBR-SIS data. However,

it should be noted that statistically significant improvements

in behavior were only obtained for Jordan, Amari, and Alex

based on DBR-SIS data. Examination of the effect sizes

obtained via DBR-SIS and SDO suggests that this finding

might be attributable to the intervention itself, rather than an

artifact of the data source. That is, for four of the students,

regardless of the data source examined, the intervention was

not very effective.

Relatively speaking, the magnitude of effects was greater

at the elementary level than the secondary level. Using inter-

pretive guidelines provided by Parker, Vannest, and Davis

(2011), Tau

novlap

DBR-SIS effect sizes were modest, falling

around the 25th percentile on average. Although the magni-

tude of these effects was lower than anticipated, several fac-

tors may have contributed to this finding. First, research has

suggested that a strong home–school collaboration compo-

nent can positively influence the effectiveness of DRC inter-

ventions (Vannest et al., 2010). Given the high needs of the

student population, teachers were generally reluctant to

include parents in the delivery of reinforcement, and instead

opted to reinforce student behavior only in the school set-

ting. Second, although efforts were made to identify students

exhibiting only a moderate level of need (e.g., excluding stu-

dents with identified disabilities), the population of students

selected for participation had higher behavioral support

needs than initially intended. In particular, the high number

of ODRs incurred for each participant suggests that these

students exhibited high levels of behavioral challenges.

Thus, they may have benefitted from more intensive and

individualized behavioral interventions. It is important to

note, however, that ODRs do not capture AE behavior and

instead capture behavioral incidents, such as instances of

defiance, DB, or aggression. Of the seven participating

teachers, six identified academic engagement as the primary

outcome of interest. Thus, while the number of ODRs

incurred for each student is informative in understanding the

nature of behavioral challenges, it does not capture the pri-

mary issue identified by teachers.

The final research question asked: Do data obtained

from DBR-SIS and SDO suggest similar or different inter-

pretations about the students’ responses to the intervention?

In light of prior research, we hypothesized that different

conclusions could be evident dependent on the data source

that was utilized. To this end, DBR-SIS and SDO data

diverged in some cases and converged in others. For exam-

ple, estimates of duration generally varied between the data

sources, which could impact goal setting and evaluations of

goal attainment. For elementary student participants, both

DBR-SIS and SDO data supported relatively similar con-

clusions. The exception to this case being Amari, whose

DBR-SIS data suggested statistically significant improve-

ments in behavior while the SDO data did not. At the ele-

mentary level, summary statistics derived from both data

sources suggested that there were improvements in student

behavior. Interestingly, this finding did not hold for

Table 2. Comparison of Progress-Monitoring Data From Study

2 (Secondary).

Pseudonym

DBR-AE

M (SD)

SDO-AE

M (SD)

Tau

novlap

DBR-SIS

Tau

novlap

SDO

Maya

Baseline 37% (29) 43% (38) .28 −.17

Intervention 48% (34) 41% (27)

Alex

Baseline 55% (19) 88% (6) .55* −.17

Intervention 76% (18) 83% (12)

Kayla

Baseline 52% (15) 77% (19) .25 −.20

Intervention 63% (25) 68% (21)

Note. DBR = Direct Behavior Rating; AE = academically engaged; SDO =

systematic direct observation; SIS = Single Item Scales.

*p < .05.

Miller et al. 45

secondary students, where DBR-SIS data suggested modest

improvements and SDO data suggested that behavior wors-

ened from baseline to intervention. Several factors may

have contributed to this finding in that (a) SDO data spanned

a shorter time frame (15 min) than DBR-SIS data (whole

target period) and (b) DBR-SIS ratings require more subjec-

tive evaluations via teacher’s perceptions. Chafouleas et al.

(2012) also found differences with regard to estimates of

duration for DBR-SIS and SDO; however, the authors cau-

tioned that different target behaviors were used between

DBR-SIS and SDO, and that future research should exam-

ine correspondence using the same target behaviors and

definitions across both methods. In the context of the cur-

rent evaluation, the same target behaviors and definitions

were utilized across DBR-SIS and SDO methods, yet dif-

ferences were still observed between methods. It may also

be the case that differences between elementary and sec-

ondary settings were due to the nature of those settings. For

example, secondary teachers typically spend less time with

specific students than elementary teachers, and perhaps this

difference affected ratings of behavior.

The results from these studies have several important

implications for practice. Because the results from these

studies were obtained using teachers as intervention agents

in actual school settings, the results have strong ecological

validity. Based on these results, there is evidence to support

the sensitivity of DBR-SIS as a formative assessment tool.

The measure was able to detect both modest and large

improvements in student behavior upon implementation of

the DRC. Results also suggested that some students did not

respond to the intervention as well as others and the mea-

sures implemented allowed for this determination to be

made. DBR-SIS demonstrated sensitivity to change, which

is an essential characteristic of progress-monitoring tools.

Data collection procedures using DBR-SIS are highly effi-

cient, and may be more feasible in school settings. Finally,

it is important to understand the strengths and limitations of

various data sources, and interpret findings within that con-

text. Clearly there are cases where DBR-SIS and SDO data

do not align, and yet decisions must be made with regard to

student response to intervention. In these cases, additional

data would be needed to triangulate such information and

make a determination.

Limitations and Future Directions

Findings from these studies must be interpreted within the

context of the limitations. This study was conducted

within a large magnet district with a small number of par-

ticipants, and so the extent to which these findings gener-

alize to different settings and participants requires further

investigation. Second, these studies were conducted with

limited parent involvement and participation. Although

DRCs were sent home to be signed and returned, parents

were not involved in the delivery of reinforcement as is

common in the DRC research literature. Therefore, it is

unclear the extent to which increased parent involvement

would have affected findings. Based on data obtained

from the URP-IR, teachers had various perceptions regard-

ing the extent to which home–school collaboration was

necessary in supporting use of the intervention. Third, stu-

dents displayed variable responsiveness to the interven-

tion. Consequently, additional research should examine

the circumstances under which DRCs are effective, and

how the intervention might be effectively tailored for non-

responders. Notably, each DRC was developed through a

series of teacher interviews, and the format and scaling of

the DRC was tailored to each student individually. Finally,

in light of impacts on decision making, future research is

needed to better understand sources of variance associated

with DBR-SIS and SDO data. Specifically, research has

suggested that teacher biases may impact ratings of stu-

dent behavior, particularly if the teacher’s race is different

from the student rated (Epstein, March, Conners, &

Jackson, 1998; Reid, Casat, Norton, Anastopoulos, &

Temple, 2001). While this prior research relied on the use

of teacher rating scales as opposed to more direct mea-

sures like DBR-SIS, additional research is needed to

investigate the possible influence of rating biases with

regard to DBR-SIS ratings.

Table 3. Social Validity Data: Usage Rating Profile–Intervention Revised.

Factor

Study 1—Elementary Study 2—Secondary

Ms. A. Ms. B. Ms. C. Ms. D. Ms. F. Ms. G. Ms. H.

Acceptability 5.7 4.1 5.0 5.0 4.9 6.0 5.3

Understanding 5.3 5.7 5.0 5.0 5.0 5.7 6.0

Home–School Collaboration 3.7 1 5.0 2.0 4.7 4.3 1.3

Feasibility 5.0 4.8 5.0 5.0 5.0 5.8 6.0

System Climate 5.0 5.6 5.0 5.0 4.8 5.8 6.0

System Support 2.0 1.0 3.0 2.0 4.0 3.7 1.0

Note. A low score on System Support is preferable as it indicates a low need for additional supports to successfully use the intervention.

46 Assessment for Effective Intervention 43(1)

Conclusion

The effective implementation of MTSS relies on the use of

evidence-based interventions and methods to monitor stu-

dent progress in response to interventions. Although options

related to evidence-based interventions continue to flourish,

a greater depth of understanding is needed with regard to

what works, for whom, and under what conditions. Central

to these determinations are the use of reliable and valid data

to inform decisions. This study provides additional evi-

dence regarding the sensitivity of DBR-SIS to detect behav-

ior change. Although questions remain regarding how to

best monitor student progress in response to behavioral

interventions, these findings suggest that DBR-SIS offers a

promising approach to formative assessment.

Authors’ Note

Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position

of the U.S. Department of Education, and such endorsements

should not be inferred.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect

to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support

for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

Preparation of this article was supported by funding provided by

the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education

(R324A110017).

References

Briesch, A. M., Chafouleas, S. M., Neugebauer, S. R., & Riley-

Tillman, T. C. (2013). Assessing influences on interven-

tion use: Revision of the Usage Rating Profile-Intervention.

Journal of School Psychology, 51, 81–96. doi:10.1016/j.

jsp.2012.08.006

Briesch, A. M., Chafouleas, S. M., & Riley-Tillman, T. C. (2010).

Generalizability and dependability of behavior assessment

methods to estimate academic engagement: Comparison of

Systematic Direct Observation and Direct Behavior Rating.

School Psychology Review, 39, 408–421.

Chafouleas, S. M. (2011). Direct Behavior Rating: A review of the

issues and research in its development. Education & Treatment

of Children, 34, 575–591. doi:10.1353/etc.2011.0034

Chafouleas, S. M., Briesch, A. M., Riley-Tillman, T. C., Christ, T.

J., Black, A. C., & Kilgus, S. P. (2010). An investigation of the

generalizability and dependability of Direct Behavior Rating

Single Item Scales (DBR-SIS) to measure academic engage-

ment and disruptive behavior of middle school students.

Journal of School Psychology, 48, 219–246. doi:10.1016/j.

jsp.2010.02.001

Chafouleas, S. M., Christ, T. K., Riley-Tillman, T. C., Briesch, A.

M., & Chanese, J. A. M. (2007). Generalizability and depend-

ability of Direct Behavior Rating to assess social behavior of

preschoolers. School Psychology Review, 36, 63–79.

Chafouleas, S. M., McDougal, J. L., Riley-Tillman, T. C., Panahon,

C. J., & Hilt, A. M. (2005). What do daily behavior report

cards (DBRCs) measure? An initial comparison of DBRCs

with direct observation for off-task behavior. Psychology in

the Schools, 42, 669–676.

Chafouleas, S. M., Riley-Tillman, T. C., & Christ, T. J. (2009).

Direct Behavior Rating (DBR): An emerging method for

assessing social behavior within a tiered intervention sys-

tem. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 34, 195–200.

doi:10.1177/1534508409340391

Chafouleas, S. M., Riley-Tillman, T. C., & McDougal, J. L.

(2002). Good, bad, or in-between: How does the daily behav-

ior report card rate? Psychology in the Schools, 39, 157–169.

doi:10.1002/pits.10027

Chafouleas, S. M., Riley-Tillman, T. C., Sassu, K. A., LaFrance,

M. J., & Patwa, S. S. (2007). Daily behavior report cards: An

investigation of the consistency of on-task data across raters

and methods. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9,

30–37.

Chafouleas, S. M., Sanetti, L. M. H., Kilgus, S. P., & Maggin,

D. M. (2012). Evaluating sensitivity to behavioral change

using Direct Behavior Rating Single-Item Scales. Exceptional

Children, 78, 491–505.

Christ, T. J., Riley-Tillman, T. C., Chafouleas, S. M., & Boice, C.

H. (2010). Direct Behavior Rating (DBR): Generalizability

and dependability across raters and observations.

Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70, 825–843.

doi:10.1177/0013164410366695

Epstein, J. N., March, J. S., Conners, C. K., & Jackson, D.

L. (1998). Racial differences on the Conners Teacher

Rating Scale. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26,

109–118.

Fuchs, L. (2004). The past, present, and future of curriculum-

based measurement research. School Psychology Review, 33,

188–192.

Gresham, F. M. (2011). Response to intervention: Conceptual

foundations and evidence based practices. In M. A. Bray & T.

J. Kehle (Eds.), Oxford handbook of school psychology (pp.

523–551). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hintze, J. M., Volpe, R. J., & Shapiro, E. S. (2002). Best practices

in the systematic direct observation of student behavior. In A.

Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychol-

ogy IV (pp. 993–1006). Bethesda, MD: National Association

of School Psychologists.

Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R.,

Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2010).

Single-case designs technical documentation. What Works

Clearinghouse. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/

Docs/ReferenceResources/wwc_scd.pdf

Miller, F. G., Patwa, S. S., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2014). Using

Direct Behavior Rating–Single Item Scales to assess student

behavior within multi-tiered systems of support. Journal of

Special Education Leadership, 27(2), 76–85.

Miller, F. G., Riley-Tillman, T. C., Chafouleas, S. M., & Schardt, A.

A. (2017). Direct Behavior Rating instrumentation: Evaluating

the impact of scale formats. Assessment for Effective

Intervention, 42, 119–126. doi: 10.1177/1534508416658007

Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., & Davis, J. L. (2011). Effect size in

single-case research: A review of nine nonoverlap techniques.

Behavior Modification, 35, 303–322.

Miller et al. 47

Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011).

Combining nonoverlap and trend for single case research:

Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42, 284–299. doi:10.1016/j.

beth.2010.08.006

Reid, R., Casat, C. D., Norton, H. G., Anastopoulos, A. D.,

& Temple, E. P. (2001). Using behavior rating scales for

ADHD across ethnic groups: The IOWA conners. Journal of

Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9, 210–218.

Riley-Tillman, T. C., Chafouleas, S. M., Sassu, K. A., Chanese,

J. A. M., & Glazer, A. D. (2008). Examining the agree-

ment of Direct Behavior Rating and Systematic Direct

Observation data for on-task and disruptive behavior.

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10, 136–143.

doi:10.1177/1098300707312542

Riley-Tillman, T. C., Methe, S. A., & Weegar, K. (2009). Examining

the use of direct behavior rating methodology on classwide

formative assessment: A case study. Assessment for Effective

Intervention, 34, 242–250. doi:10.1177/1534508409333879

Suen, H. K., Ary, D., & Covalt, W. (1991). Reappraisal of momen-

tary time sampling and partial-interval recording. Journal

of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24, 803–804. doi:10.1901/

jaba.1991.24-803

Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., Davis, C. R., Mason, B. A., & Burke,

M. D. (2010). Effective intervention for behavior with a daily

behavior report card: A meta-analysis. School Psychology

Review, 39, 654–672.

Vannest, K. J., Parker, R. I., & Gonen, O. (2011). Single Case

Research: Web based calculators for SCR analysis (Version

1.0) [Web-based application]. College Station: Texas A&M

University. Available from singlecaseresearch.org

Venn, J. (2012). Current issues in assessing students with special

needs. In C. F. Webber & J. L. Lupart (Eds.), Leading student

assessment (pp. 133–150). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Volpe, R. J., & Briesch, A. M. (2012). Generalizability and

dependability of single-item and multiple-item direct behav-

ior rating scales for engagement and disruptive behavior.

School Psychology Review, 41, 246–261.

Volpe, R. J., & Fabiano, G. A. (2013). Daily behavior report

cards: An evidence-based system of assessment and interven-

tion. New York, NY: Guilford.