AVIATIONSAFETY

ActionsNeededto

EvaluateChangesto

FAA’sEnforcement

PolicyonSafety

Standards

Accessible Version

August 2020

ReporttoCongressionalCommittees

GAO-20-642

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-20-642, a report to

congressional committees

August 2020

AVIATION SAFETY

Actions Needed to Evaluate Changes to FAA’s

Enforcement Policy on Safety Standards

What GAO Found

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) directed individual offices to

implement the Compliance Program, and FAA has increasingly used compliance

actions rather than enforcement actions to address violations of safety standards

since starting the Compliance Program. FAA revised agency-wide guidance in

September 2015 to emphasize using compliance actions, such as counseling or

changes to policies. Compliance actions are to be used when a regulated entity

is willing and able to comply and enforcement action is not required or warranted,

e.g., for repeated violations, according to FAA guidance. FAA then directed its

offices—for example, Flight Standards Service and Drug Abatement Division—to

implement the Compliance Program as appropriate, given their different

responsibilities and existing processes. Under the Compliance Program, data

show that selected FAA offices have made increasing use of compliance actions.

Total Number of Federal Aviation Administration Enforcement Actions and Num ber of

Compliance Actions Closed for Selected Program Offices, Fiscal Years 2012-2019

No specific FAA office or entity oversees the Compliance Program. FAA tasked a

working group to lead some initial implementation efforts. However, the group no

longer regularly discusses the Compliance Program, and no office or entity was

then assigned oversight authority. As a result, FAA is not positioned to identify

and share best practices or other valuable information across offices. FAA

established goals for the Compliance Program—to promote the highest level of

safety and compliance with standards and to foster an open, transparent

exchange of data. FAA, however, has not taken steps to evaluate if or determine

how the program accomplishes these goals. Key considerations for agency

enforcement decisions state that an agency should establish an evaluation plan

to determine if its enforcement policy achieves desired goals. Three of eight FAA

offices have started to evaluate the effects of the Compliance Program, but two

offices have not yet started. Three other offices do not plan to do so—in one

case, because FAA has not told the office to. FAA officials generally believe the

Compliance Program is achieving its safety goals based on examples of its use.

However, without an evaluation, FAA will not know if the Compliance Program is

improving safety or having other effects—intended or unintended.

View GAO-20-642. For more information,

contact Heather Krause at (202) 512-2834 or

krauseh@gao.gov.

Why GAO Did This Study

FAA supports the safety of the U.S.

aviation system by ensuring air

carriers, pilots, and other regulated

entities comply with safety

standards. In 2015, FAA announced

a new enforcement policy with a

more collaborative and problem-

solving approach called the

Compliance Program. Under the

program, FAA emphasizes using

compliance actions, for example,

counseling or training, to address

many violations more efficiently,

according to FAA. Enforcement

actions such as civil penalties are

reserved for more serious violations,

such as when a violation is reckless

or intentional.

The FAA Reauthorization Act of

2018 included a provision that GAO

review FAA’s Compliance Program.

This report examines (1) how FAA

implemented and used the

Compliance Program and (2) how

FAA evaluates the effectiveness of

the program. GAO analyzed FAA

data on enforcement actions

agency-wide and on compliance

actions for three selected offices for

fiscal years 2012 to 2019 (4 years

before and after program start).GAO

also reviewed FAA guidance and

interviewed FAA officials, including

those from the eight offices that

oversee compliance with safety

standards.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three

recommendations including that

FAA assign authority to oversee the

Compliance Program and evaluate

the effectiveness of the program in

meeting goals. FAA concurred with

the recommendations.

Page i GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Contents

Letter 1

Background 4

FAA Directed Individual Program Offices to Implement the

Compliance Program, and Data Show an Increase in Use of

Compliance Actions 11

FAA Has Taken Limited Actions to Monitor and Evaluate the

Effectiveness of Its Compliance Program 25

Conclusions 34

Recommendations for Executive Action 35

Agency Comments 36

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 37

Appendix II: Additional Analysis of Federal Aviation Administration’s Enforcement Data 45

Appendix III: Comments from the Department of Transportation 54

Appendix IV: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 56

GAO Contact 56

Staff Acknowledgments 56

Appendix V: Accessible Data 57

Data Tables 57

Agency Comment Letter 71

Tables

Table 1: Federal Aviation Administration Program (FAA) Offices,

Oversight Responsibilities, and Inspection Staff 8

Table 2: Examples of Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA)

Program Office Guidance before and after the Start of the

Compliance Program 15

Table 3: Number of Enforcement Actions Closed by Federal

Aviation Administration (FAA) Program Offices, Fiscal

Years 2012 and 2019 19

Page ii GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Table 4: List of Industry Associations, Unions, and Regulated

Entities Interviewed by GAO 44

Table 5: Number of Actions Resulting from Cases That Initiated an

Enforcement Action for Federal Aviation Administration

(FAA) Certificate Types That Comprise a Majority of all

Actions, Fiscal Years 2012 to 2019 49

Table 6: Number of Actions Resulting from Cases That Initiated an

Enforcement Action by Type and by Regional Office, by

Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019 51

Table 7: Amounts of Proposed and Final Civil Penalties for

Enforcement Actions by Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019 52

Figures

Figure 1: Description of Compliance and Enforcement Actions

Available to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) 7

Figure 2: Examples of Federal Aviation Administration’s Safety

Standards and Aviation Stakeholders 9

Figure 3: Summary of the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA)

Enforcement Policy and Guidance Prior to and under the

Compliance Program 12

Figure 4: Total Number of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

Enforcement Actions and Number of Compliance Actions

Closed for Three Selected Program Offices, Fiscal Years

2012–2019 17

Figure 5: Number and Type of Federal Aviation Administration

(FAA) Enforcement Actions, by Fiscal Year Closed,

2012–2019 18

Figure 6: Median Number of Days Taken to Close Federal

Aviation Administration (FAA) Enforcement Actions,

Fiscal Years 2012–2019 20

Figure 7: Number of Non-enforcement Actions for Selected

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Program Offices,

Fiscal Years 2014-2019 22

Figure 8: Median Number of Days to Close Non-enforcement

Actions for Selected Federal Aviation Administration

(FAA) Program Offices, Fiscal Years 2016-2019 24

Figure 9: Number of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Cases

That Initiated an Enforcement Action, by Fiscal Year

Closed, 2012–2019 46

Page iii GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Figure 10: Number and Type of Actions Resulting from Federal

Aviation Administration (FAA) Cases That Initiated an

Enforcement Action, by Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019 47

Figure 11: Number of Actions from Cases That Initiated an

Enforcement Action by Federal Aviation Administration

(FAA) Program Office, by Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019 48

Figure 12: Number of Actions Resulting from Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA) Cases That Initiated an

Enforcement Action by Violation Category, by Fiscal Year

Closed, 2012–2019 50

Figure 13: Median Number of Days for Proposed and Final

Sanctions for Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

Enforcement Actions Involving Certificates by Fiscal Year

Closed, 2012–2019 53

Accessible Data for Total Number of Federal Aviation

Administration Enforcement Actions and Number of

Compliance Actions Closed for Selected Program

Offices, Fiscal Years 2012-2019 57

Accessible Data for Figure 1: Description of Compliance and

Enforcement Actions Available to the Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA) 58

Accessible Data for Figure 2: Examples of Federal Aviation

Administration’s Safety Standards and Aviation

Stakeholders 59

Accessible Data for Figure 3: Summary of the Federal Aviation

Administration’s (FAA) Enforcement Policy and Guidance

Prior to and under the Compliance Program 60

Accessible Data for Figure 4: Total Number of Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA) Enforcement Actions and Number

of Compliance Actions Closed for Three Selected

Program Offices, Fiscal Years 2012–2019 61

Accessible Data for Figure 5: Number and Type of Federal

Aviation Administration (FAA) Enforcement Actions, by

Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019 62

Accessible Data for Figure 6: Median Number of Days Taken to

Close Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Enforcement

Actions, Fiscal Years 2012–2019 63

Accessible Data for Figure 7: Number of Non-enforcement Actions

for Selected Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

Program Offices, Fiscal Years 2014-2019 64

Accessible Data for Figure 8: Median Number of Days to Close

Non-enforcement Actions for Selected Federal Aviation

Page iv GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Administration (FAA) Program Offices, Fiscal Years

2016-2019 65

Accessible Data for Figure 9: Number of Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA) Cases That Initiated an

Enforcement Action, by Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019 66

Accessible Data for Figure 10: Number and Type of Actions

Resulting from Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

Cases That Initiated an Enforcement Action, by Fiscal

Year Closed, 2012–2019 67

Accessible Data for Figure 11: Number of Actions from Cases

That Initiated an Enforcement Action by Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA) Program Office, by Fiscal Year

Closed, 2012–2019 68

Accessible Data for Figure 12: Number of Actions Resulting from

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Cases That

Initiated an Enforcement Action by Violation Category, by

Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019 69

Accessible Data for Figure 13: Median Number of Days for

Proposed and Final Sanctions for Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA) Enforcement Actions Involving

Certificates by Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019 70

Page v GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Abbreviations

CCMIS Certification and Compliance Management Information

System

CETS Compliance and Enforcement Tracking System

DOT Department of Transportation

EIS Enforcement Information System

FAA Federal Aviation Administration

ICAO International Civil Aviation Organization

PTRS Program Tracking and Reporting Subsystem

SAS Safety Assurance System

SMS safety management system

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

Letter

August 18, 2020

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Technology

United States Senate

The Honorable Peter A. DeFazio

Chairman

The Honorable Sam Graves

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The U.S. airspace system is one of the safest in the world. The Federal

Aviation Administration (FAA), within the Department of Transportation

(DOT), helps ensure the safety of the system by overseeing and

enforcing safety standards for air carriers, pilots, airports, and other parts

of the aviation system. In accordance with broader agency changes to a

more proactive, data-driven approach to overseeing safety, FAA

announced a change to its enforcement policy in June 2015 through the

Compliance Program. According to FAA, the Compliance Program

emphasizes an open, problem-solving approach to examine and address

violations of safety standards in law and regulation.

1

As such, the

program emphasizes collaboration and use of compliance actions, such

as counseling or training, to address violations. However, FAA continues

to use a range of more punitive enforcement actions, including assessing

civil penalties and suspending a person’s or entity’s certificate, when

warranted, to try to ensure that regulated entities comply with safety

standards.

While FAA implemented this change to its enforcement policy to improve

safety, recent events have raised questions about the effectiveness of

1

FAA, Order 8000.373, Federal Aviation Administration Compliance Philosophy, June 26,

2015. Initially known as the Compliance Philosophy, FAA renamed this change to its

enforcement and compliance policy to the Compliance Program in 2018.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

FAA’s enforcement efforts. For example, DOT’s Office of Inspector

General reported that FAA allowed one airline to continue to operate

aircraft for nearly 2 years, even though many of its aircraft were out of

compliance with weight and balance regulations.

2

The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 included a provision for GAO to

review FAA’s enforcement policy under the Compliance Program.

3

This

report

· describes how FAA has implemented and used the Compliance

Program, and

· examines how FAA monitors and evaluates the effectiveness of its

Compliance Program.

To describe how FAA implemented and used the Compliance Program,

we reviewed current and prior FAA-wide guidance on compliance and

enforcement.

4

We also reviewed guidance and manuals for the eight

program offices responsible for overseeing regulated entities’ compliance

with safety standards to understand how these offices applied the

Compliance Program to their responsibilities. These program offices are

listed in table 1 of the report.

5

We interviewed FAA officials from these

program offices and the Enforcement Division in the Office of Chief

Counsel to further understand implementation and use of the Compliance

Program.

In addition, we analyzed FAA data to examine FAA’s use of compliance

and enforcement actions over time. Specifically:

· First, we analyzed Enforcement Information System (EIS) data on

enforcement actions closed for fiscal years 2012 through 2019.

2

DOT Office of Inspector General, FAA Has Not Effectively Overseen Southwest Airlines’

Systems for Managing Safety Risks, AV2020019 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2020).

3

Pub. L. No. 115-254, § 324, 132 Stat. 3186, 3271. While FAA refers to its new approach

as the Compliance Program, it is a change in the agency’s enforcement policy.

4

This includes versions FAA Order 2150, FAA Compliance and Enforcement Program .

5

We did not include examining FAA’s designee program or organization authorization

designation program in our review. Through these programs, FAA authorizes individuals

or organizations, respectively, to conduct exams, perform tests, and issue approvals and

certificates on behalf of FAA. One example of organization delegation authorization is

when the organization is responsible for managing the engineering and manufacturi ng

approvals needed to issue type certificates or supplemental type certificates for aircraft.

Letter

Page 3 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

We selected this time period to cover 4 years before and after the

start of the Compliance Program and to include the most recent

full fiscal year of available data.

6

· Second, we analyzed data on compliance actions as well as

informal actions (i.e., non-enforcement actions) for three selected

program offices to examine the number of such actions closed for

fiscal years 2014 through 2019. The program offices were Flight

Standards Service, the Drug Abatement Division, and Airport

Safety and Standards.

7

We chose these program offices to vary in

terms of size (e.g., number of inspectors), number of enforcement

actions taken in years prior to the Compliance Program, and

availability of data, among other criteria.

We assessed the reliability of each data source by reviewing documents

and interviewing knowledgeable agency officials, among other things. We

determined that the data sources were sufficiently reliable for our

purposes of describing the number and type of actions FAA used over

time.

To examine how FAA monitors and evaluates the Compliance Program,

we reviewed FAA-wide guidance and other information. We also

interviewed FAA officials in the Enforcement Division and all eight

program offices to understand efforts to monitor and evaluate the

effectiveness of the Compliance Program. We compared FAA’s efforts to

(1) federal internal control standards for establishing structure,

responsibility, and authority; designing control activities; and using quality

information; and (2) key considerations for agency design and

enforcement decisions.

8

6

Data from EIS included several types of actions. These actions include legal enforcement

actions, such as civil penalties; administrative actions, such as w arning letters; referrals to

other agencies; and no actions, meaning the collected evidence did not support the finding

of a violation. We reported on all of these actions in EIS collectively as enforcement

actions unless otherwise noted.

7

Informal actions are non-enforcement actions that FAA could use to address less serious

violations prior to the Compliance Program. Two selected program offices—Flight

Standards and Airport Safety and Standards—used informal actions prior to the start of

the Compliance Program. For these offices, we analyzed available data on informal

actions for fiscal years prior to the Compliance Program.

8

See GAO, Federal Regulations: Key Considerations for Agency Design and Enforcement

Decisions, GAO-18-22 (Washington, D.C.: Oct.19, 2017) and Standards for Internal

Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 20, 2014).

Letter

Page 4 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

To inform both objectives, we interviewed 11 selected industry

associations, two unions representing FAA inspectors in the selected

program offices, and eight selected regulated entities (e.g., air carriers,

airports) to gather their views on the implementation and use of the

Compliance Program. We selected industry associations to align with the

operations overseen by the selected program offices and to cover a range

of aviation operations. We selected regulated entities to also align with

the selected program offices and to vary by size and location. The

information and viewpoints obtained from these interviews cannot be

generalized to all industry associations, FAA inspectors, or regulated

entities but offer insight into understanding the issues examined in this

report. Appendix I contains more information on our objectives, scope,

and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2019 to August 2020 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Over the last several decades, FAA has evolved its oversight of aviation

safety in response to changes in the industry and technologies. Due to

increasing complexity of the aviation system, FAA has stated that it

cannot rely on traditional, enforcement-based oversight to further improve

safety. In particular, FAA has stated that new technologies and users,

such as unmanned aircraft system (i.e., drone) users, mean that it cannot

wait for violations and accidents to occur but must take a more proactive

approach to identify and address potential new safety hazards. More

specifically, the low accident rate in the U.S. aviation system reflects the

importance of analyzing less serious incidents and available data for

causes and indicators of potential hazards, rather than identifying these

hazards after the fact when investigating accidents. In 2005, FAA began

implementing a data-driven and risk-based safety management system

(SMS) oversight approach. SMS is a formalized process that involves

collecting and analyzing data on aviation operations to identify emerging

safety problems, determining risk severity, and mitigating that risk to an

Letter

Page 5 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

acceptable level.

9

In addition, FAA’s transition to its more proactive

oversight approach aligns with applicable global standards for safety

management and the international aviation community.

10

FAA describes the Compliance Program as a part of the agency’s shift to

a proactive, risk-based oversight approach. Under the Compliance

Program, FAA aims to collaborate with regulated entities to address the

root cause of any violations of safety standards upfront, using counseling,

remedial training, or other compliance actions, when possible.

11

In this

manner, FAA states that it aims to identify and correct violations as

effectively, quickly, and efficiently as possible. FAA’s goals for the

Compliance Program, according to FAA, are to (1) promote the highest

level of safety and compliance with regulatory standards and (2) foster an

open and transparent exchange of data.

12

According to FAA guidance,

when a regulated person is willing and able to comply with safety

standards and the conduct does not meet the criteria for legal

enforcement action, FAA will resolve the issue with a compliance action.

However, according to this guidance, FAA will use enforcement actions

when it finds evidence of reckless, intentional, or criminal behavior, such

9

FAA started implementing SMS in 2005. This type of approach is recognized by aviation

leaders and aligns with global standards for aviation. For more information on SMS, see

GAO, Aviation Safety: Additional Oversight Planning by FAA Could Enh ance Safety Risk

Management, GAO-14-516 (Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2014).

10

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) adopted standards and

recommended practices covering safety management and safety management systems

between 2001 and 2007. ICAO encouraged civil aviation authorities, including FAA, to

issue regulations to implement safety management systems across their service providers

such as air carriers and maintenance organizations. ICAO is an agency of the United

Nations that promotes the safe and orderly development of international civil aviation

worldwide. ICAO has 193 member states.

11

We use the term violation in this report, but FAA and other agencies often refer to

violations as noncompliances or deviations. As outlined in FAA guidance, the Compliance

Program also can be used to address any non -regulatory safety concerns. In particular,

FAA personnel can use a compliance action to encourage regulated persons to adopt

FAA-recommended best practices to address safety concerns that are not regulatory in

nature. See FAA, Order 2150.3C. For the purposes of our report, we focused on FAA’s

actions to address violations.

12

FAA, Order 8000.373.

Letter

Page 6 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

as a pilot deliberately flying into restricted airspace without clearance, or

when FAA identifies a significant safety risk.

13

FAA is not unique in its decision to emphasize compliance over

enforcement. In October 2017, we reported that federal agencies

generally have the flexibility to tailor their compliance and enforcement

strategies. In particular, we reported that selected agencies often adapted

the appropriate mix of compliance assistance, together with monitoring

and enforcement efforts, to ensure safety and other positive outcomes.

14

For example, we reported that when the Food and Drug Administration

identifies a violation, it may not immediately use an enforcement action.

Instead, it may begin with a meeting or call with the regulated entity to

address the issue and gradually implement more serious measures as

needed.

Although the Compliance Program emphasizes use of compliance actions

in certain circumstances, FAA can still use enforcement actions to

address instances of noncompliance (see fig. 1).

13

FAA personnel are required in some circumstances and have discretion in other

circumstances to refer matters to FAA’s Enforcement Division to evaluate using legal

enforcement action and, if appropriate, initiating a legal enforcement action. For example,

FAA personnel are required to refer matters that arise from a regulated person’s failure to

complete corrective action, where legal enforcement action is required by law, and where

a certificate holder lacks the care, judgment, or responsibility to hold the certificate. FAA

personnel have the discretion to take legal enforcement action in other instances, such as

where a person has committed repeated violations. FAA, Order 2150.3C, Chapter 5.

14

GAO-18-22. This report examined how selected federal agencies made decisions

related to regulatory design, compliance and enforcement, and updating regulations .

Letter

Page 7 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Figure 1: Description of Compliance and Enforcement Actions Available to the

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

Note: FAA Order 2150.3 outlines the circumstances for which legal enforcement action is required. In

such circumstances FAA personnel are required to refer matters to FAA ’s Enforcement Division for

evaluation and, if appropriate, initiation of legal enforcement action against a regulated person. FAA

personnel also have the discretion to refer matters for legal enforcement action for other

circumstances detailed in guidance.

Inspectors and staff in eight program offices within FAA are responsible

for overseeing regulated entities’ compliance with safety standards (see

table 1).

Letter

Page 8 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Table 1: Federal Aviation Administration Program (FAA) Offices, Oversight Responsibilities, and Inspection Staff

Program office

Examples of oversight responsibilities

Number of reported

inspection staff

a

Aircraft Certification Service

Provides oversight of persons involved in the production and

manufacture of aircraft and aircraft parts.

818

Commercial Space Transportation

Regulates the U.S. commercial-space transportation industry, including

protecting persons, property, and national security during commercial

launch or reentry activities.

19

Drug Abatement Division, Office

of Aerospace Medicine

Oversees the aviation industry’s compliance with drug and alcohol testing

laws and regulations, covering safety-sensitive employees such as pilots,

mechanics, and flight dispatchers at aviation companies.

49

Flight Standards Service

Provides standards, certification, and oversight of a variety of persons,

aircraft, and aircraft operations. For example, regulates air carriers,

commercial and general aviation pilots, unmanned aircraft system (i.e.,

drone) users, and aviation mechanics.

3,267

Medical Certification Division,

Office of Aerospace Medicine

Oversees airman medical certification and investigates cases involving

an airman’s medical qualifications, including issuing or denying

applications based on whether an applicant meets medical standards set

forth in regulation.

n/a

b

Office of Airport Safety and

Standards

Oversees airports that meet specific thresholds for scheduled and

unscheduled air carrier operations. For example, inspects pavement

conditions, runway lighting, and aircraft rescue and firefighting training at

these airports.

57

Office of Hazardous Materials

Safety

Oversees entities that offer, accept, or transport hazmat to, from, or

within the United States or on U.S. registered aircraft. Regulated entities

include the operators that transport hazmat, businesses that handle or

offer hazmat, and individuals (e.g., passengers with hazmat in luggage).

95

Office of National Security

Programs and Incident Response

Investigates the failure of pilots with certificates to timely provide reports

of driving under the influence/driving while intoxicated motor vehicle

actions and investigates intentional falsifications and incorrect statements

on applications for medical certificates. Also provides assistance to

federal, state, local, and other law enforcement agencies investigating

areas that overlap with FAA regulatory responsibilities (e.g., transporting

prohibited drugs by aircraft).

27

Source: GAO analysis of FAA documents and interviews with FAA officials. | GAO-20-642

a

Number of inspection staff as reported to GAO by program offices in fall 2019.

b

The Medical Certification Division does not employ inspector staff. Aviation medical examiners

designated by the FAA evaluate applications and conduct physical examinations necessary for

determining qualification for medical certificates, and may issue or defer medical certificates based on

w hether an applicant meets medical standards set forth in regulation. Cases involving potential

falsifications or incorrect statements on applications for medical certification are referred to FAA ’s

Enforcement Division.

All aviation stakeholders play a role in ensuring the safety of the aviation

system. For example, regulated persons such as pilots, airlines, and

airports are responsible for complying with applicable safety standards.

FAA inspectors and other staff conduct inspections, investigations, and

other means of surveillance to help ensure regulated entities understand

and comply with standards. FAA also relies on regulated entities to share

Letter

Page 9 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

data and information on safety risks and violations to aid its efforts to

improve aviation safety. Air traffic controllers and local law-enforcement

officials provide FAA investigative personnel with information on possible

violations, such as a pilot not following instructions from air traffic control,

to prompt an FAA investigation. Figure 2 highlights some of these

stakeholders and examples of FAA safety standards.

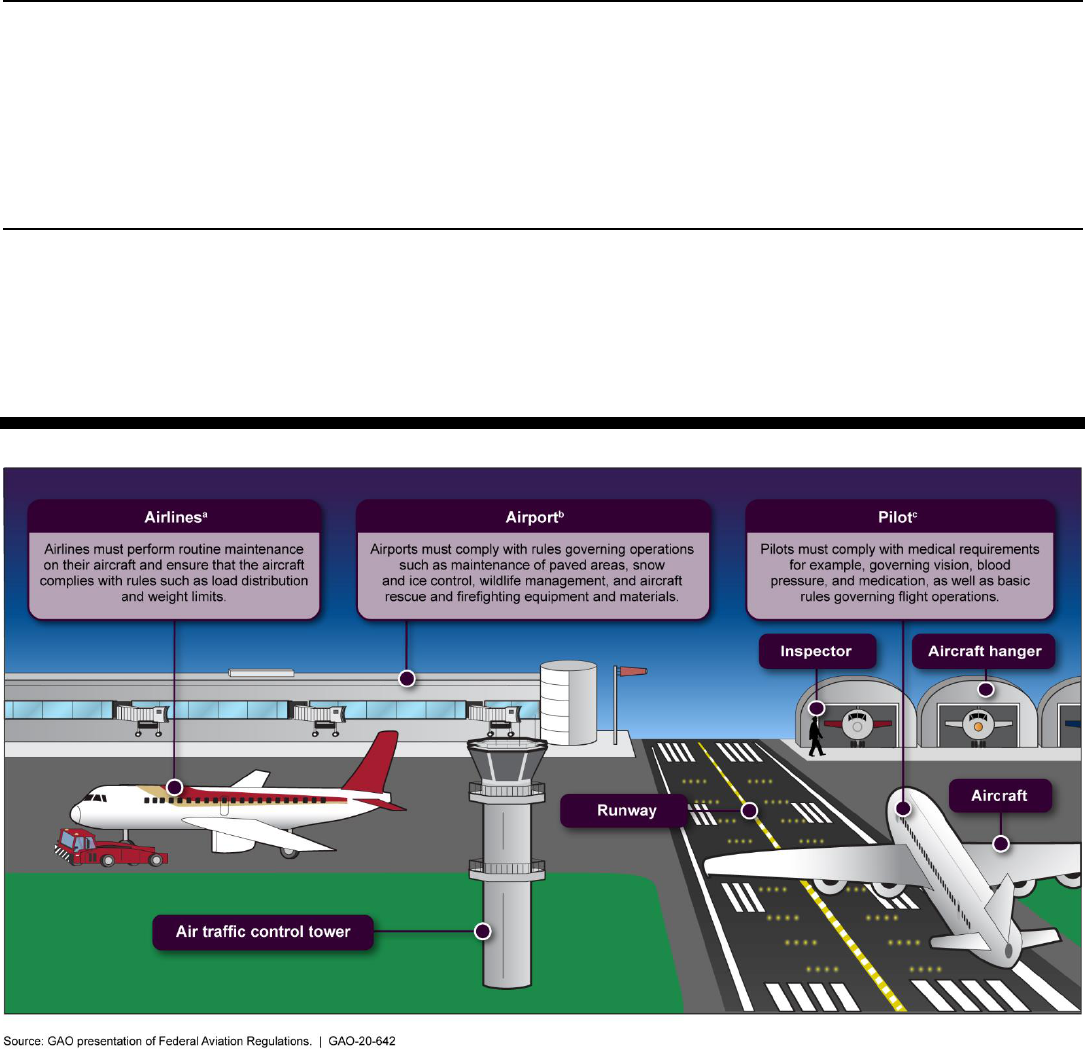

Figure 2: Examples of Federal Aviation Administration’s Safety Standards and Aviation Stakeholders

a

14 C.F.R. Part 25 (larger aircraft), 14 C.F.R. Part 23 (smaller aircraft).

b

14 C.F.R. Part 139.

c

14 C.F.R. Part 61, 14 C.F.R. Part 91.

After an FAA inspector identifies and confirms a violation, the inspector is

responsible for recommending the appropriate action to address the

violation. The inspector’s recommended compliance or enforcement

Letter

Page 10 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

action and related information are to be reviewed by managers.

15

In

addition, any proposed legal enforcement action is to be sent to FAA’s

Enforcement Division in the Office of the Chief Counsel. The Enforcement

Division is responsible for evaluating and, if appropriate, initiating legal

enforcement action.

16

Legal enforcement actions as well as administrative

actions are tracked in FAA’s enforcement database, EIS. During the

manager’s or legal counsel’s review, the type of action and any related

sanction, like the number of days to suspend a certificate, may change.

17

A decision that no action is warranted can also be made.

15

One FAA program office—the Office of Hazardous Materials Safety—does not use

compliance actions to address violations involving non -certificated persons, such as

shippers or freight forwarders. Instead, this office uses informal actions —typically oral or

written counseling—or administrative and legal enforcement actions, to address violations

involving non-certificated persons.

16

FAA program offices are to create an enforcement investigative report for cases with a

proposed legal enforcement action(s). This report is to be sent to the Enforcement

Division and information on the case, violations, and proposed and final actions is entered

into EIS.

17

FAA changed its guidance on September 18, 2018, so that inspectors in most program

offices would no longer propose a sanction amount. According to FAA officials, this

change allowed the agency to speak with one voice about sanction amounts. In particular,

FAA officials said the Enforcement Division selects the final sanction based o n guidance

in FAA Order 2150. One program office—Hazardous Materials Safety—retained the ability

for its inspectors to recommend sanction amounts.

Letter

Page 11 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

FAADirectedIndividual ProgramOfficesto

Implement theComplianceProgram,andData

ShowanIncreaseinUseofCompliance

Actions

FAAUpdatedEnforcementPolicyandGuidanceto

IncorporatetheComplianceProgram

Adoption of the Compliance Program changed FAA’s emphasis from

enforcement to compliance actions to promote safety. When violations

occur, FAA states that it aims to use the most effective means to return

the regulated entity to full compliance and prevent recurrence. In addition,

according to FAA documents, FAA believes that when violations occur

due to, for example, flawed procedures or simple mistakes, compliance

actions such as training or improvements to procedures can most

effectively address the violation. The primary way FAA operationalized

this was by changing guidance for FAA’s inspectors on which type of

actions to take in response to violations. For example, in September

2015, FAA’s Enforcement Division updated the agency-wide guidance to

outline the general circumstances under which the agency may use a

compliance action, administrative action, and legal enforcement action.

As noted above, the guidance describes that legal enforcement action is

appropriate for cases involving, among other things, conduct that is

intentional or reckless or that creates or threatens to create an

unacceptable risk to safety.

18

The Compliance Program gives inspectors more leeway to choose

compliance actions over enforcement actions. Figure 3 summarizes

changes to agency-wide guidance prior to and then under the

Compliance Program.

18

FAA, Order 2150.3C, Chapter 5.

Letter

Page 12 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Figure 3: Summary of the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) Enforcement

Policy and Guidance Prior to and under the Compliance Program

Although non-enforcement actions were previously allowed, the

Compliance Program now encourages FAA inspectors to use non-

enforcement actions to address violations when appropriate. Prior to the

Compliance Program, agency-wide guidance permitted inspectors to use

informal actions—which are non-enforcement actions—under certain

conditions.

19

For example, an inspector could take an informal action,

such as oral or written counseling, or an administrative action to address

violations that presented a low risk of occurring or causing damage.

However, officials in three of seven FAA field offices we interviewed said

that it was difficult to use an informal action in the past as the

19

Prior to the Compliance Program, investigative personnel could take an admi nistrative or

informal action if the case met eight criteria: (1) legal enforcement action was not required

by law; (2) administrative action would have been an adequate deterrent to future

violations; (3) lack of qualification was not indicated; (4) the a pparent violation was

inadvertent, i.e., not the result of purposeful conduct; (5) a substantial disregard for safety

or security was not involved; (6) the circumstances of the apparent violation were not

aggravated; (7) the alleged violator had a constructive attitude toward compliance; and (8)

a trend of noncompliance was not indicated. If all eight criteria were met, the inspector had

to evaluate whether the risk of the apparent violation was high , medium, or low, per the

potential severity and likelihood of the hazard. Investigators could take an informal action

for apparent violations that presented a low risk. In addition, if a lack of qualification is

evidenced by a lack of the care, judgment, and responsibility to hold that certificate, FAA

personnel were to refer the matter for legal enforcement action evaluation.

Letter

Page 13 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Enforcement Decision Process pushed them to pursue enforcement

actions.

20

Moreover, officials in five of seven FAA field offices said the

Compliance Program now encourages inspectors to use compliance

actions when appropriate. By encouraging use of compliance actions,

officials in four of these offices said they have greater flexibility to better

address the cause of a violation.

21

FAA officials in six of seven field

offices said that it is easier to get a regulated entity’s cooperation and

attention under the Compliance Program. They said that this is because

inspectors can work with the entity to take action to address potential or

realized problems rather than to simply recommend an enforcement

action.

In addition to updating agency-wide guidance, FAA leadership tasked a

risk-based decision-making working group to guide initial implementation

of the Compliance Program. During the spring of 2014, the working

group, which was composed of staff from various program offices, began

developing goals, drafting an Order outlining the Compliance Program,

and creating a communications plan to announce it.

22

FAAProgramOfficesImplementedtheCompliance

ProgramatTheirOwnDiscretion

In addition to updating agency-wide guidance, FAA also directed each

program office to implement the Compliance Program according to each

20

We used open-ended questions to guide our interviews with officials in FAA field offices.

Here and throughout the draft, we present the number of field offices for which a topic or

view was raised during the discussion; the remaining field offices did not specifically

comment on the topic or view.

21

FAA Order 2150.3C requires a legal enforcement action when a regulated person’s

noncompliance arises from: (1) intentional conduct; (2) reckles s conduct; (3) failure to

complete a corrective action; (4) creating or threatening to create an unacceptable risk to

safety; or (5) an act where the express terms of a statute or regulation require initiation of

a legal enforcement action. In addition, if a lack of qualification is evidenced by a lack of

the care, judgment, and responsibility to hold that certificate, FAA personnel refer the

matter for legal enforcement action evaluation.

22

According to FAA, this working group’s meetings aimed to execute on e part of the FAA’s

risk-based decision-making strategic initiative—to evolve the safety oversight model to

leverage industry's use of safety management principles, and to exchange safety-

management lessons learned and best practices. This strategic initia tive covered several

past and ongoing items, including implementing the Compliance Program, developing

standardized safety oversight terminology for FAA, and conducting a gap analysis of

FAA’s oversight policies, processes, and tools.

Letter

Page 14 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

office’s differing oversight responsibilities and existing processes. FAA’s

program offices oversee regulated entities that vary from individuals to

large companies. These offices also oversee compliance with rules that

range from drug testing to record keeping to transporting hazardous

materials. FAA officials said that each program office therefore

implemented the Compliance Program at its own discretion consistent

with agency-wide guidance.

23

According to these officials, the risk-based

decision-making working group provided a forum for program office

officials to share information during implementation. For example, during

such meetings, program offices shared updates on the status of

implementing the Compliance Program within their respective offices,

according to officials from one program office.

Most program offices implemented the Compliance Program by creating

or updating their guidance to align with the new enforcement policy in

agency-wide guidance. Officials from seven of eight program offices told

us they created or updated their guidance to incorporate the Compliance

Program during fall 2015 or later.

24

However, the extent of changes made

to guidance varied across program offices based on several factors,

including the following:

· A few program offices frequently used informal actions prior to the

Compliance Program. These program offices, therefore, already

had language or processes in their guidance to account for using

non-enforcement actions. For example, officials from one program

office said they used informal actions in the past for violations that

did not have a safety effect, such as signing a form with black

rather than the required blue ink. Once the Compliance Program

was implemented, this office further formalized guidance on when

to use compliance actions. Other program offices that rarely used

or did not use informal actions had to make more changes to

guidance to reflect the new approach.

· As FAA’s agency-wide guidance shifted from the Enforcement

Decision Process to broader, more flexible guidance, some

23

This agency-wide guidance is outlined in FAA Order 2150.3C, Chapter 5, as of May

2020.

24

Officials from the Medical Certification Division said the office was excluded from the

Compliance Program because it involves whether a medical standard is met. That is, the

decision to issue or deny a medical certificate is based on whether a pilot meets the

medical standards set forth in regulation, or whether limitations can be added to the

medical certificate to allow issuance. Therefore, the office has not made any changes to

its guidance or procedures.

Letter

Page 15 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

program offices had to develop their own specific processes to

replace the Enforcement Decision Process. For example, one

program office created a new worksheet with steps for inspectors

to use to identify the action to take for a violation. A second

program office also created a worksheet with a decision tree to

help inspectors determine the action to take based on the risk

associated with a violation.

Table 2 below provides examples of how program offices updated their

guidance to implement the Compliance Program.

Table 2: Examples of Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) Program Office Guidance before and after the Start of the

Compliance Program

Program office

Guidance prior to the Compliance Program

Guidance under Compliance Program

Drug Abatement Division

Inspectors were required to use either an

administrative or legal enforcement action when

they discovered a violation.

Inspectors may use a compliance action to

address most violations that used to result in

administrative actions.

Flight Standards

Inspectors could use an administrative action for

violations that presented a moderate-risk or an

informal action to address low-risk violations.

Inspectors can use a compliance action to

address instances of violations as long as the

person is willing and able to comply and the

conduct does not meet criteria for using legal

enforcement action.

Office of Airport Safety and

Standards

Inspectors worked with airports to educate and

assist them with compliance as required, and

inspectors used an informal action (that took the

form of a letter) to address any violations.

Inspectors can use a compliance action (that

continues to take the form or a letter) to address

any violations.

Source: GAO analysis of FAA documents and interviews with FAA officials. | GAO-20-642

Program offices took steps to communicate about the Compliance

Program and changes in guidance to staff as they deemed appropriate,

recognizing the varying size and purpose of their office. Seven program

offices reported offering training to announce and implement the

Compliance Program. In one program office, training on the Compliance

Program was offered to managers before training was offered to all of the

workforce. FAA officials said the program office did this because it

believed that managers needed to first understand and support the

Compliance Program for it to be successful. Four program offices also

reported holding town hall or all-staff meetings to present the Compliance

Program and new guidance to staff. One of these program offices

supplemented these meetings with presentations to explain the

Compliance Program and associated changes in guidance to staff.

Letter

Page 16 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

DataShowThatEnforcementActionsHaveDecreased

andBeenOffsetbyComplianceActionssince2015

Mix of Compliance Actions and Enforcement Actions

Our analysis of FAA data found that the total number of enforcement

actions, counted by the fiscal year the actions were closed, decreased

across the agency under the Compliance Program. At the same time, the

number of compliance actions closed for three selected program offices

has increased since the start of the Compliance Program (see fig. 4).

25

According to FAA officials, this shift aligns with what FAA officials

expected would happen under the Compliance Program.

25

While data on enforcement actions are tracked centrally, individual program offices track

data on compliance actions. We selected three program offices—Flight Standards

Service, Drug Abatement Division, and Airport Safety and Standards—to examine the

number and type of compliance actions taken by FAA. See appendix I for more

information on how we selected program offices and the data we examined from these

offices.

Letter

Page 17 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Figure 4: Total Number of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Enforcement

Actions and Number of Compliance Actions Closed for Three Selected Program

Offices, Fiscal Years 2012–2019

Notes: Enforcement actions includes (1) legal enforcement actions like civil penalties and suspending

or revoking a regulated entity’s certificate and (2) administrative actions like w arning letters and

letters of correction.

The number of compliance action are based on data for three selected program offices: Flight

Standards Service, Airport Safety and Standards, and Drug Abatement.

Enforcement Actions

As noted above, the number of enforcement actions closed decreased

after the start of the Compliance Program. The number of legal

enforcement actions closed decreased slightly from fiscal year 2012 to

fiscal year 2019 (see fig. 5). However, the number of administrative

actions closed declined more substantially from above 6,000 to under

2,000 per year over this period. There was a notable decrease in

administrative actions from 2015 to 2016 following the start of the

Compliance Program.

Letter

Page 18 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Figure 5: Number and Type of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Enforcement Actions, by Fiscal Year Closed, 2012–2019

Looking further at the change in enforcement actions, all but one of eight

program offices had a decrease in the number of enforcement actions

closed from fiscal year 2012 to 2019 (see table 3).

26

Flight Standards had

the greatest decrease in the number of enforcement actions closed. This

outcome is not a surprise as Flight Standards has historically initiated the

most enforcement actions and is responsible for the majority of FAA’s

oversight. Only the Medical Certification Division saw an increase in the

number of enforcement actions over this time period, mostly during the

last 3 years. Officials from this program office said the increase is

possibly due to changes associated with the start of BasicMed in 2017, a

program that provides certain pilots that meet specific requirements

26

The count of enforcement actions in this section includes lega l enforcement and

administrative actions tracked in FAA’s EIS database. See appendix I for further detail.

Letter

Page 19 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

potential relief from having to hold a medical certificate.

27

Table 3: Number of Enforcement Actions Closed by Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Program Offices, Fiscal Years 2012

and 2019

FAA program office

a

2012

b

2019

Percentage change

Aircraft Certification

280

28

(90)

Flight Standards

4,998

881

(82)

Hazardous Materials Safety

1,788

578

(68)

Airport Safety and Standards

3

0

(100)

Drug Abatement

1,289

345

(73)

National Security Programs and Incident Response

579

378

(35)

Medical Certification

142

451

218

Source: GAO analysis of FAA’s Enforcement Information System database. | GAO-20-642

a

Commercial Space is not included in the table as it did not take any enforcement actions during fiscal

years 2012 through 2017, so w e could not look at change over the 8-year period for this program

office.

b

Enforcement actions include (1) legal enforcement actions like civil penalties and suspending or

revoking a regulated entity’s certificate and (2) administrative actions like w arning letters and letters of

correction.

While FAA is using fewer enforcement actions, our analysis of data found

that the time needed to process and close these actions has not

decreased. According to FAA, it expected that the greater use of

compliance actions would help decrease the time it takes the agency to

process all types of actions and allow it to target resources to more

egregious cases. For enforcement actions, we found that it is taking FAA

roughly the same amount of time to process administrative actions and

more time to close legal enforcement actions since the start of the

Compliance Program (see fig. 6).

27

The FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016, Pub. L. No. 114-190, § 2307, 130

Stat. 615, 641, permits pilots who would normally be required to hold a third -class medical

certificate to forego the process under certain conditions and instead fly under a new

process and standards. FAA named this process and standards BasicMed. Pilots could

use BasicMed if they held a driver’s license, held a medical certificate after July 1 5, 2006,

got a physical exam that used a specific checklist, and completed a medical education

course, among other requirements. A pilot cannot use BasicMed if their medical

certification application has ever been denied, suspended, revoked , or withdrawn. With

the start of BasicMed, according to FAA officials, the FAA determined that it could not

allow applications to remain open indefinitely without a decision while awaiting information

needed from an applicant to determine if the applicant is medically qualified. The start of

BasicMed provided a potential opportunity for these applicants to instead apply through

BasicMed, because their application for medical certification had neve r been denied,

suspended, revoked, or withdrawn.

Letter

Page 20 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Figure 6: Median Number of Days Taken to Close Federal Aviation Administration

(FAA) Enforcement Actions, Fiscal Years 2012–2019

FAA officials said legal enforcement actions involve different steps and

circumstances than administrative or compliance actions, and such steps

can contribute to more time being needed to close legal enforcement

actions. First, a legal enforcement action may require specific events to

occur before it is closed, even after FAA issues the action. For example,

the officials said that FAA will not close a civil penalty, one type of legal

enforcement action, until all payments of the penalty are made. Second,

Enforcement Division officials said the cases for legal enforcement action

they have received in recent years are more complex. These cases, such

as those involving illegal charter operations or requiring emergency action

to suspend a pilot’s medical or other certificate, take longer to process

and close.

28

Finally, FAA officials said that other factors outside the

agency’s control, including appeals of legal enforcement actions, affect

28

For example, due to BasicMed, the Enforcement Division initiates more emergency

orders to suspend medical certificates than in the past, according to FAA officials. FAA

officials said that these cases require the immediate surrender of medical certificates, but

the suspension remains pending, or open, until the certificate holder provides the

requested information and qualifies for an unrestricted airman medical certification.

Therefore, FAA cannot close a case and the corresponding actions until the suspended

medical certificate expires, which can take several years .

Letter

Page 21 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

how long it takes to close an action. Regarding the sharp increase in

fiscal year 2016, FAA officials said it is likely due to an internal initiative to

clean up FAA’s enforcement data system. For the initiative, Enforcement

Division staff identified cases left in open or pending status in the system

but requiring no further work and subsequently took steps to close them.

Also, while FAA is taking fewer enforcement actions, the amounts

obtained in civil penalties and amounts of other sanctions associated with

legal enforcement actions has not lessened according to our analysis of

FAA data. For actions involving civil penalties, the median amount of the

final civil penalty that FAA assessed fluctuated but generally ranged

between $5,000 and $6,000 over the 8 years of data we analyzed.

29

In

contrast, for actions involving certificate actions, mainly suspensions, the

median number of days FAA suspended an entity’s certificate has

increased in recent years, from 60 days to 90 days.

Compliance Actions

Based on data for the three selected program offices we reviewed, the

number of non-enforcement actions—informal and compliance—

increased since the start of the Compliance Program. Examining by fiscal

year closed, the use of these actions increased overall after the start of

the program, though year-to-year changes differed by program office.

(See fig. 7.)

29

The median amount of civil penalties recommended by the regional office and legal

counsel decreased over the 8 years we analyzed. For the last 3 years, the median amount

recommended by the regional office and legal counsel moved closer to the final median

amount assessed for civil penalties. In September 2018, FAA changed its guidance so

that most offices no longer propose a sanction amount; rather, legal counsel determine

the sanction amount using tables on sanction amounts included in FAA guidance . See

appendix II for more detail on civil penalties and other sanctions related to enforcement

actions and additional analysis of FAA’s EIS data.

Letter

Page 22 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Figure 7: Number of Non-enforcement Actions for Selected Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA) Program Offices, Fiscal Years 2014-2019

Notes: The Drug Abatement Division did not use informal actions under FAA policy prior to the

Compliance Program. For the other tw o program offices, data w ere available for informal actions for

both offices for fiscal years 2014 and 2015.

Informal actions and compliance actions both represent non-enforcement action available to FAA.

Compliance actions did not exist prior to the start of the Compliance Program.

The increase in non-enforcement actions, including the large increase in

compliance actions closed by Flight Standards, was driven by the start of

the Compliance Program, as well as other factors according to FAA

officials. Officials from the three selected program offices identified factors

beyond the start of the Compliance Program that influenced some year-

to-year changes in the number of informal and then compliance actions

closed. Airport Safety and Standards, for example, extensively used

informal actions prior to the Compliance Program. However, an official

from this program office said that the recent increase in compliance

actions is primarily due to its new effort to identify emphasis areas for

inspections that started in 2017. Due to this new effort, FAA officials from

this office said that inspectors tend to identify more violations in the

Letter

Page 23 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

emphasis areas and as a result have taken more compliance actions for

these violations. FAA officials also said they have seen a decrease in the

number of compliance actions in these areas in subsequent years as

airports learn from and receive additional training to correct mistakes.

We also found the length of time it takes the three selected program

offices to close compliance actions has not decreased over time. As

shown in figure 8, the median number of days for these program offices to

close these actions has not gone down, based on the fiscal year closed.

Officials from one regulated entity we spoke with said that FAA and the

entity had been taking a longer time to close compliance actions due to

the higher volume of compliance actions it receives from FAA. According

to FAA officials, inspectors can leave a compliance action open as long

as needed to ensure a regulated entity has addressed the problem.

However, according to FAA guidance, inspectors must also ensure that

applicable time limits do not prevent FAA from taking further action, such

as a legal enforcement action, if the regulated entity fails to address the

problem to FAA’s satisfaction.

30

30

FAA guidance notes that it may consider a progressive response to repeated

noncompliance. For example, if a corrective action does not remediate a noncompliance,

it may be appropriate for FAA personnel to pursue legal enforcement action. However,

FAA may be prevented from taking an enforcement action if it does not comply with

certain time limits in regulation. For example, FAA must file a notice of proposed civil

penalty within 2 years from the date of an apparent violation under 14 C.F.R. § 13.208(d).

Failure to comply with these time limits could p reclude the FAA from bringing legal

enforcement action or result in the dismissal of a case .

Letter

Page 24 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

Figure 8: Median Number of Days to Close Non-enforcement Actions for Selected

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Program Offices, Fiscal Years 2016-2019

Notes: The selected program offices track different dates that can be used to mark the start of an

informal or compliance action. Therefore, the median number of days it took to close an informal or

compliance action across offices cannot be directly compared.

The Drug Abatement Division tracks dates using month and year, so w e tracked time to close actions

in monthly increments.

Flight Standards’ Safety Assurance System data w e analyzed, which cover a limited number of

actions closed in 2018 and 2019, did not include a date w e could use to mark the start of a

compliance action. Therefore, time to close actions for Flight Standards includes only actions from the

Program Tracking and Reporting System.

Letter

Page 25 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

FAAHasTakenLimitedActionstoMonitorand

EvaluatetheEffectivenessofItsCompliance

Program

FAAHasNotAssignedAuthoritytoOverseethe

ComplianceProgram

FAA implemented the Compliance Program in a decentralized manner,

directing program offices to tailor it to their specific needs. FAA initially

relied on a working group for centralized leadership during initial

implementation. According to officials who participated in the group, the

meetings served as an opportunity for program office officials to ask

questions about the Compliance Program and better understand FAA’s

expectations for the program. Although the working group still meets

regularly, according to the officials that lead this group, it is now focused

on other efforts, and currently the group does not regularly monitor or

discuss the Compliance Program.

31

While initially tasked with some

aspects of its implementation, FAA officials said the working group is not

directly responsible for the Compliance Program.

No specific office or entity is responsible for overseeing the ongoing use

of the Compliance Program across FAA. Federal standards for internal

control state that an agency should establish structure, assign

responsibility, and delegate authority to achieve the agency’s objectives.

32

In particular, an agency should develop an organizational structure with

an understanding of overall responsibilities, and assign these

responsibilities to discrete units to enable it to operate in an efficient and

effective manner. A sound internal control environment also requires that

an agency consider how its units interact to fulfill their overall

responsibilities and establishes appropriate lines of reporting. Based on

our review of FAA documents and our prior review of FAA’s enforcement

policy, FAA’s oversight used to be more centralized in the Enforcement

Division, where all administrative and legal enforcement actions were

31

These other efforts include performing a comprehensive gap-analysis of FAA’s oversight

processes. The gap analysis involves FAA offices comparing their existing policies and

procedures to the requirements of FAA’s Integrated Oversight Philosophy. Once these

gaps are identified, offices will update their policies and procedures to align with

requirements.

32

GAO-14-704G, Principle 3.

Letter

Page 26 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

tracked in a single database.

33

Now, as FAA emphasizes compliance

actions over enforcement actions, tracking of actions is less centralized

and occurs more in individual program offices, according to FAA officials.

Without a centralized oversight entity, no one is looking across program

offices to identify or share any best practices or lessons learned. We

previously reported (1) that the independent nature of FAA offices creates

challenges for implementing safety initiatives within FAA and (2) that the

agency could improve internal communication to advance safety efforts.

34

This observation is also applicable for the Compliance Program, as

individual offices have information that might benefit other offices. For

example, Flight Standards surveyed its workforce to systematically collect

feedback when initially implementing the Compliance Program. A

centralized oversight entity could facilitate Flight Standards’ sharing

information on this practice with other offices, such as the survey

methodology or any actions it took in response to what it learned from the

survey. Further, officials from one FAA field office told us that the

Compliance Program could be improved by better sharing information on

its use across the agency. These officials noted that there are lessons to

be learned from how other program offices are using this and other

related safety programs.

In the past, FAA has assigned a single authority to coordinate other

safety efforts, including efforts that cross FAA program offices. For

example, in 2008, FAA established the SMS Committee to coordinate the

implementation of SMS across the agency. Specific offices that oversaw

the detailed implementation of SMS internally and externally then

reported directly to the SMS Committee.

35

Besides the working group,

FAA also has several options for offices or entities that could oversee the

Compliance Program, such as the following:

33

GAO, Aviation Safety: Better Management Controls are Needed to Improve FAA’s

Safety Enforcement and Compliance Efforts, GAO-04-646 (Washington, D.C.: July 6,

2004)

34

GAO, Aviation Safety: Additional FAA Efforts Could Enhance Safety Risk Management,

GAO-12-898 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2012) and GAO, Aviation Safety: Opportunities

Exist for FAA to Improve Airport Terminal Area Safety Efforts, GAO-19-639 (Washington,

D.C.: Aug. 30, 2019).

35

GAO-12-898. Additionally, FAA established the SMS Executive Council, composed of

high-level officials from each program office to oversee the implementation of SMS. The

SMS Committee reported directly to the SMS Executive Council.

Letter

Page 27 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

· Flight Standards, the largest of the eight program offices, created

a team that continues to lead and oversee implementation of the

Compliance Program in that program office.

· The Enforcement Division within the Office of Chief Counsel

provides guidance on compliance and enforcement actions

agency-wide and processes cases referred for civil penalties and

other legal enforcement actions.

A centralized oversight entity could enable improved information sharing

and direction across program offices that use the Compliance Program.

FAAHasCollectedLimitedAgencyWideDatatoMonitor

ComplianceProgram

Program offices collect data and track some measures related to the

Compliance Program, but FAA is no longer regularly collecting that data

centrally as it did during initial implementation. FAA officials said that

during the initial implementation of the Compliance Program, program

offices discussed using data to help gauge how each office was using the

Compliance Program during risk-based decision-making working group

meetings. In particular, they discussed measures that could be used in

presentations to the FAA Executive Council. FAA officials said that each

program office individually determined what measures to track quarterly.

Ultimately, the separate offices tracked data for many of the same

measures. For example, seven program offices reported tracking the

number of enforcement actions taken. Six program offices reported

tracking the number of compliance actions taken. Program offices also

chose to track data for other measures that ranged from the number of

reports made by regulated entities to voluntarily disclose violations, to the

time needed to close actions.

36

Although most FAA program offices reported tracking data on the

Compliance Program, no one office is collecting and analyzing the data

36

FAA has several programs that allow voluntary self-disclosure reports through which

regulated entities share information regarding an instance of non -compliance with FAA

through a designated program. Submitting a report protects the entity from an

enforcement action if the appropriate process is followed. For example, the Office of

Hazardous Materials Safety operates its Voluntary Disclosure Reporting Program for air

carriers to disclose violations of the Hazardous Materials Regulations without receiving a

civil penalty, if the process is followed correctly.

Letter

Page 28 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

on an ongoing basis to communicate a comprehensive picture of how the

program is working across offices. FAA has not assigned an office or

entity to continue to oversee the Compliance Program since the risk-

based decision-making working group completed its implementation work.

Federal standards for internal control state that an agency should design

control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks.

37

A control

activity could include, for example, a review at the functional or office

level to compare actual performance to expected results and to analyze

major differences. Federal standards for internal control also state that an

agency should internally communicate the necessary quality information

to achieve its objectives.

38

Currently, some program office data are

assembled into agency-wide presentations to brief the executive council,

inspector general, or other groups, but this activity is done as needed

rather than on a regular basis. The presentations compile specific

information on use of the Compliance Program, presenting it office by

office. The presentations do not, however, look across offices to present a

comprehensive message on the health of the program agency-wide

based on the data collected.

FAA is missing the opportunity to use available program office data to

monitor use of the Compliance Program across the agency. In the course

of our review, we analyzed data from three program offices and identified

changes over time. Some of these changes differed across the three

offices, such as the number of compliance actions closed each year since

the Compliance Program started. Other changes were similar across

offices; for example, the time each office is taking to close compliance

actions has not decreased over time. Monitoring such information across

offices could help FAA manage the Compliance Program, such as

determining if data suggests changes might be needed to agency-wide

guidance or if program offices need to take additional action to train

37

GAO-14-704G, Principle 10.

38

GAO-14-704G, Principle 14.

Letter

Page 29 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program

staff.

39

With a broader review of available data, FAA will also be better

positioned to know if observations from data for the three program offices

we examined hold true for other program offices as well.

40

Leadership

officials of one program office said they need to examine similarities in

how their and other program offices have implemented the Compliance

Program, a process that could then help FAA find ways to summarize

data across offices. Collecting and using this data for the Compliance

Program across program offices would also align with FAA’s broader

strategic initiative to integrate and standardize data.

41

By regularly collecting and monitoring data on use of the Compliance

Program, FAA would also be positioned to use what is found or learned in

additional ways, such as sharing information on the program with

stakeholders outside the agency.

42

Officials from ten industry associations

and organizations we spoke with stated they had not seen any data from

FAA on the use of the Compliance Program. Officials from two

associations noted that FAA had shared only limited data, such as counts

of compliance and enforcement actions taken by a single program office.

Moreover, officials from one industry association told us that FAA could

share more information on the types of actions it takes, or on types of

violations that lead to use of enforcement actions each year. The officials

39

In December 2019, the DOT Inspector General reported that FAA did not provide its

inspectors with guidance and comprehensive training to ensure that an airline, Allegiant

Air, took effective action to correct violations. Specifically, the Inspector General

recommended that FAA revise its guidance to clarify how inspectors address recurring

violations as a factor in considering whether to initiate compliance or enforcement actions.

The Inspector General also recommended that FAA perform a comprehensive review of

its root-cause analysis training for inspectors, as it found current training was insufficient.

U.S. DOT Office of Inspector General, FAA Needs to Improve Its Oversight To Address

Maintenance Issues Impacting Safety at Allegiant Air, AV202013 (Washington, D.C.: Dec.

17, 2019).

40

In presentations of program office data, each office’s information is presented

individually, but the data are not connected across offices for a look at the program’s use

agency-wide. Additionally, some program offices also face data limitations.

41

FAA’s 2019 strategic priorities include, as part of its systemic safety approach, specific

initiatives to build on safety management principles and to improve the collection,

management, and integration of safety data to enhance safety analysis across the

agency. FAA Strategic Plan FY 2019-2022.

42

In our October 2017 report on key considerations to strengthen agency decisions related

to regulatory design and enforcement, we reported that transparency and availability of

data are important to promoting compliance and achieving regulatory objectives .

GAO-18-22.

Letter

Page 30 GAO-20-642 FAA’s Compliance Program