Key Substance Use and

Mental Health Indicators

in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National

Survey on Drug Use and Health

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Acknowledgments

is report was prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), under Contract No. HHSS283201700002C with

RTI International. Rachel N. Lipari and Eunice Park-Lee were the SAMHSA authors. Peter Tice served as the

government project officer and as the contracting officer representative.

Public Domain Notice

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission

from SAMHSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. However, this publication may not be reproduced or

distributed for a fee without the specific, written authorization of the Office of Communications, SAMHSA, HHS.

Electronic Access and Printed Copies

is publication may be downloaded or ordered at https://store.samhsa.gov. Or call SAMHSA at

1-877-SAMHSA-7 (1-877-726-4727) (English and Español).

Recommended Citation

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health

indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication

No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality,

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Originating Office

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,

5600 Fishers Lane, Room 15-E09D, Rockville, MD 20857. For questions about this report, please e-mail

Nondiscrimination Notice

SAMHSA complies with applicable federal civil rights laws and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color,

national origin, age, disability, or sex. SAMHSA cumple con las leyes federales de derechos civiles aplicables y no

discrimina por motivos de raza, color, nacionalidad, edad, discapacidad o sexo.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality

Populations Survey Branch

August 2019

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health August 2019

|

iii

Summary ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1

Introduction ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������5

Survey Background ��������������������������������������������������������������������5

Data Presentation and Interpretation ������������������������������������������5

Substance Use in the Past Month �����������������������������������������������6

Tobacco Use in the Past Month ��������������������������������������������������� 7

Cigarette Use ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������8

Daily Cigarette Use ������������������������������������������������������������������������9

Alcohol Use in the Past Month ��������������������������������������������������10

Any Alcohol Use ��������������������������������������������������������������������������10

Binge Alcohol Use ������������������������������������������������������������������������11

Heavy Alcohol Use �����������������������������������������������������������������������11

Illicit Drug Use in the PastYear �������������������������������������������������12

Any Illicit Drug Use ����������������������������������������������������������������������12

Marijuana Use �����������������������������������������������������������������������������13

Cocaine Use ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������14

Heroin Use ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������15

Methamphetamine Use ����������������������������������������������������������������15

Hallucinogen Use �������������������������������������������������������������������������16

Inhalant Use ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������17

Misuse of Psychotherapeutic Drugs ����������������������������������������������17

Stimulant Misuse �������������������������������������������������������������������������18

Tranquilizer or Sedative Misuse ����������������������������������������������������18

Benzodiazepine Misuse ����������������������������������������������������������������19

Pain Reliever Misuse �������������������������������������������������������������������20

Opioid Misuse �����������������������������������������������������������������������������23

Initiation of Substance Use �������������������������������������������������������24

Initiation of Cigarette Use �������������������������������������������������������������24

Initiation of Alcohol Use ����������������������������������������������������������������25

Initiation of Marijuana Use ������������������������������������������������������������25

Initiation of Cocaine Use ���������������������������������������������������������������26

Initiation of Heroin Use �����������������������������������������������������������������26

Initiation of Methamphetamine Use �����������������������������������������������27

Initiation of Hallucinogen Use��������������������������������������������������������27

Initiation of Inhalant Use ���������������������������������������������������������������28

Initiation of Stimulant Misuse��������������������������������������������������������28

Initiation of Tranquilizer or Sedative Misuse �����������������������������������28

Initiation of Pain Reliever Misuse ��������������������������������������������������29

Perceived Risk from Substance Use �����������������������������������������30

Perceived Risk from Substance Use among Adolescents ����������������30

Perceived Risk from Substance Use among Young Adults ���������������31

Perceived Risk from Substance Use among Adults Aged

26 or Older ����������������������������������������������������������������������������32

Substance Use Disorders in the PastYear ��������������������������������32

Alcohol Use Disorder �������������������������������������������������������������������32

Illicit Drug Use Disorder����������������������������������������������������������������33

Marijuana Use Disorder ����������������������������������������������������������������35

Cocaine Use Disorder ������������������������������������������������������������������35

Heroin Use Disorder ���������������������������������������������������������������������36

Methamphetamine Use Disorder ���������������������������������������������������37

Stimulant Use Disorder ����������������������������������������������������������������37

Tranquilizer Use Disorder or Sedative Use Disorder ������������������������38

Pain Reliever Use Disorder �����������������������������������������������������������38

Opioid Use Disorder ���������������������������������������������������������������������39

Substance Use Disorder (Alcohol or Illicit Drugs) ����������������������������39

Major Depressive Episode in the PastYear ������������������������������� 41

MDE and MDE with Severe Impairment among Adolescents �����������41

MDE and MDE with Severe Impairment among Adults ��������������������42

Any Mental Illness among Adults in the PastYear ��������������������43

Serious Mental Illness among Adults in the PastYear ��������������43

Co‑Occurring MDE and SUD among Adolescents ����������������������44

Substance Use among Adolescents with MDE �������������������������� 45

Co‑Occurring Mental Health Issues and SUD among Adults �����45

Co‑Occurring AMI and SUD ����������������������������������������������������������45

Co‑Occurring SMI and SUD ����������������������������������������������������������46

Substance Use among Adults with Mental Health Issues ���������47

Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior among Adults ������������������������� 47

Serious Thoughts of Suicide ���������������������������������������������������������48

Suicide Plans ������������������������������������������������������������������������������48

Suicide Attempts �������������������������������������������������������������������������49

Substance Use Treatment in the PastYear �������������������������������50

Need for Substance Use Treatment �����������������������������������������������50

Receipt of Substance Use Treatment ���������������������������������������������50

Perceived Need for Substance Use Treatment ��������������������������������53

Reasons for Not Receiving Specialty Substance Use Treatment �������54

Mental Health Service Use in the PastYear ������������������������������55

Treatment for Depression among Adolescents �������������������������������55

Treatment for Depression among Adults ����������������������������������������55

Any Mental Health Service Use among All Adolescents �������������������57

Any Mental Health Service Use among All Adults ���������������������������58

Any Mental Health Service Use among Adults with AMI ������������������59

Table of Contents

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Healthiv

|

August 2019

Any Mental Health Service Use among Adults with SMI ������������������60

Perceived Unmet Need for Mental Health Services

among Adults with Mental Illness

���������������������������������������������61

Receipt of Services for Co‑Occurring Substance Use

Disorder and Mental Health Issues �������������������������������������������63

Receipt of Services among Adolescents with

Co‑Occurring MDE and a Substance Use Disorder ��������������������63

Receipt of Services among Adults with Co‑Occurring AMI

and a Substance Use Disorder

�������������������������������������������������64

Receipt of Services among Adults with Co‑Occurring SMI

and a Substance Use Disorder

�������������������������������������������������65

Endnotes �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������67

AppendixA: Supplemental Tables of Estimates for Key

Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the

United States �������������������������������������������������������������������������� A‑1

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health August 2019

|

1

Summary

is report summarizes key findings from the 2018 National

Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for national

indicators of substance use and mental health among people

aged 12 or older in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population

of the United States. Results are provided for the overall category

of people aged 12 or older and by age subgroups.

Substance Use

In 2018, an estimated 164.8 million people aged 12 or older

in the United States (60.2 percent) were past month substance

users (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs). About 2 out of 5

people aged 12 or older (108.9 million, or 39.8 percent) did not

use substances in the past month. e 164.8 million past month

substance users in 2018 include 139.8 million people who drank

alcohol, 58.8 million people who used a tobacco product, and

31.9 million people who used an illicit drug.

Tobacco Use

In 2018, an estimated 47.0 million people aged 12 or older

were past month cigarette smokers, including 27.3 million

people who were daily cigarette smokers and 10.8 million

daily smokers who smoked approximately a pack or more

of cigarettes per day. Fewer than 1 in 6 people aged 12 or

older in 2018 were past month cigarette smokers. Cigarette

use generally declined between 2002 and 2018 across all

age groups. Some of this decline may reflect the use of

electronic vaporizing devices (“vaping”), such as e-cigarettes,

as a substitute for delivering nicotine. NSDUH does not

currently ask separate questions about the vaping of nicotine.

Alcohol Use

In 2018, about 139.8 million Americans aged 12 or older

were past month alcohol users, 67.1 million were binge

drinkers in the past month, and 16.6 million were heavy

drinkers in the past month.

1

About 2.2 million adolescents

aged 12 to 17 drank alcohol in the past month, and

1.2 million of these adolescents binge drank in that period.

Although the percentage of adolescents who drank alcohol

decreased between 2002 and 2018, about 1 in 11 adolescents

in 2018 were past month alcohol users.

1

NSDUH collects information on past month alcohol use, binge alcohol use,

and heavy alcohol use. For men, binge alcohol use is defined in NSDUH as

drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the

past 30 days. For women, binge drinking is defined as drinking four or more

drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days. Heavy

alcohol use is defined as binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past 30 days.

Illicit Drug Use

In 2018, nearly 1 in 5 people aged 12 or older (19.4 percent)

used an illicit drug in the past year, which is a higher

percentage than in 2015 and 2016. e estimate of past year

illicit drug use for 2018 was driven primarily by marijuana

use, with 43.5 million past year marijuana users. e

percentage of people aged 12 or older in 2018 who used

marijuana in the past year (15.9 percent) was higher than

the percentages in 2002 to 2017. is increase in past year

marijuana use for people aged 12 or older reflects increases

in marijuana use among both young adults aged 18 to 25

and adults aged 26 or older. In contrast, past year marijuana

use among adolescents aged 12 to 17 did not increase

between 2014 and 2018.

Prescription pain reliever misuse was the second most

common form of illicit drug use in the United States in

2018, with 3.6 percent of the population misusing pain

relievers. For people aged 12 or older and for young adults

aged 18 to 25, the percentages who misused prescription

pain relievers in the past year were lower in 2018 than in

2015 to 2017. Similar decreases in pain reliever misuse were

observed for adolescents aged 12 to 17 and adults aged 26 or

older in 2018 compared with 2015 and 2016 but not when

compared with 2017. Among people aged 12 or older in

2018 who misused pain relievers in the past year, the most

common main reason for their last misuse of a pain reliever

was to relieve physical pain (63.6 percent). More than half

(51.3 percent) of people who misused pain relievers in the

past year obtained the last pain reliever they misused from a

friend or relative.

NSDUH also allows for estimation of opioid misuse, which

is defined as the use of heroin or the misuse of prescription

pain relievers. In 2018, an estimated 10.3 million people

aged 12 or older misused opioids in the past year, including

9.9 million prescription pain reliever misusers and 808,000

heroin users. Approximately 506,000 people misused

prescription pain relievers and used heroin in the past year.

e percentage of people aged 12 or older in 2018 who were

past year opioid misusers was lower than the percentages

between 2015 and 2017, which was largely driven by

declines in pain reliever misuse rather than by changes in

heroin use.

Substance Use Initiation

In 2018, the substances with the largest number of recent

(i.e., past year) initiates of use or misuse were alcohol

(4.9 million new users), marijuana (3.1 million new users),

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health2

|

August 2019

1.7 million people with a prescription pain reliever use

disorder and 0.5 million people with a heroin use disorder.

Although the percentage of people with an SUD in

2018 was similar to the percentages in 2015 to 2017, the

corresponding percentages of the population with a pain

reliever use disorder, opioid use disorder, or alcohol use

disorder were lower than in 2015.

Major Depressive Episode

In 2018, about 1 in 7 adolescents aged 12 to 17

(14.4 percent) had a past year major depressive episode

(MDE), or 3.5 million adolescents. About 1 in 10

adolescents (10.0 percent) had a past year MDE with severe

impairment, or 2.4 million adolescents.

3

e percentage of

adolescents in 2018 who had a past year MDE was higher

than the percentages in 2004 to 2017.

In 2018, approximately 13.8 percent of young adults aged

18 to 25 (4.6 million) had an MDE during the past year, and

8.9 percent (3.0 million) had a past year MDE with severe

impairment. e percentage of young adults in 2018 who

had a past year MDE was greater than the percentages in

2005 to 2016, but it was similar to the percentage in 2017.

Mental Illness among Adults

In 2018, an estimated 47.6 million adults aged 18 or older

(19.1 percent) had any mental illness (AMI) in the past year.

An estimated 11.4 million adults in the nation had serious

mental illness (SMI) in the past year, corresponding to

4.6 percent of all U.S. adults.

4

e percentages of adults

aged 18 or older in 2018 with AMI or SMI were similar to

the corresponding percentages in 2017, but they were higher

than the percentages in most years from 2008 to 2016.

Percentages of young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2018 who

had AMI or SMI also were greater than the corresponding

percentages in each year from 2008 to 2016, but they were

similar to the percentages in 2017.

3

People who met the criteria for MDE based on criteria specified in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5),

were defined as having an MDE. See the following reference: American

Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

4

Adults with AMI were defined as having any mental, behavioral, or

emotional disorder in the past year that met DSM-IV criteria (excluding

developmental disorders and SUDs). Adults with AMI were defined as

having SMI if they had any mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder that

substantially interfered with or limited one or more major life activities.

See footnote 2 for the reference for the DSM-IV criteria.

prescription pain relievers (1.9 million new misusers), and

cigarettes (1.8 million new users). Although the number

of marijuana initiates aged 12 or older in 2018 was higher

than the numbers in 2002 to 2016, it was similar to that

in 2017. e number of people aged 12 or older in 2018

who initiated the misuse of prescription pain relievers was

similar to the numbers in 2015 to 2017. In 2018, among

adolescents aged 12 to 17 and young adults aged 18 to 25,

however, the numbers of new misusers of pain relievers were

lower than the numbers in 2015 and 2016.

Perceived Risk from Substance Use

In 2018, more than 4 out of 5 people aged 12 or older

perceived great risk of harm from weekly use of cocaine or

heroin (86.5 and 94.3 percent, respectively), while less than

one third of people (30.6 percent) perceived great risk of

harm from weekly marijuana use. About 2 out of 3 people

(68.5 percent) perceived great risk from daily binge drinking,

and nearly 3 out of 4 people (71.8 percent) perceived great

risk from smoking one or more packs of cigarettes per day.

Perceptions of risk from this level of daily cigarette use or

weekly marijuana and cocaine use among people were lower

in 2018 than in 2015. However, the percentages of people

in 2018 who perceived great risk from weekly heroin use

or daily binge drinking were similar to the corresponding

percentages in 2015 to 2017. Among adolescents aged 12

to 17 in 2018, there were declines in the percentages who

perceived great risk from this level of daily cigarette use

(smoking one or more packs per day) and weekly marijuana

use, but the percentages who perceived great risk from daily

binge drinking, weekly cocaine use, or weekly heroin use

were similar to prior years.

Substance Use Disorders

In 2018, approximately 20.3 million people aged 12 or

older had a substance use disorder (SUD) related to their

use of alcohol or illicit drugs in the past year, including

14.8 million people who had an alcohol use disorder and

8.1 million people who had an illicit drug use disorder.

2

e most common illicit drug use disorder was marijuana

use disorder (4.4 million people). An estimated 2.0 million

people had an opioid use disorder, which includes

2

People who met the criteria for dependence or abuse for alcohol or illicit

drugs in the past 12 months based on criteria specified in the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), were

defined as having an SUD. See the following reference: American Psychiatric

Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(DSM-IV) (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health August 2019

|

3

Co‑Occurring Mental Health Issues and Substance Use

Disorders

Approximately 358,000 adolescents (1.5 percent of all

adolescents) had an SUD and an MDE in the past year,

including 288,000 adolescents (1.2 percent of all

adolescents) who had an SUD and an MDE with severe

impairment. e percentages of adolescents who had an

SUD and an MDE or who had an SUD and an MDE with

severe impairment remained steady from 2015 to 2018.

In 2018, an estimated 9.2 million adults aged 18 or older

(3.7 percent of all adults) had both AMI and at least one

SUD in the past year, and 3.2 million adults (1.3 percent

of all adults) had co-occurring SMI and an SUD in the

past year. e 2018 percentages of adults with both AMI

and an SUD and adults with both SMI and an SUD were

higher than the corresponding percentages in 2015 and

2016, but they were similar to the percentages in 2017.

Substance Use among People with Mental Health

Issues

In 2018, substance use was more common among both

adolescents and adults who had a mental health issue than

among those who did not have a mental health issue. About

1 in 16 adolescents aged 12 to 17 in 2018 (6.1 percent)

with a past year MDE smoked cigarettes in the past month

compared with 2.1 percent of those without a past year

MDE. In addition, adolescents with an MDE were more

likely than those without an MDE to binge drink in the

past month (8.5 vs. 4.1 percent) and to use an illicit drug in

the past year (32.7 vs. 14.0 percent).

Among adults aged 18 or older in 2018, an estimated

28.1 percent of adults with AMI and 37.2 percent of

adults with SMI were cigarette smokers in the past month

compared with 16.3 percent of those without any mental

illness. In addition, 31.3 percent of adults with AMI and

32.3 percent of adults with SMI were binge drinkers in the

past month compared with 25.3 percent of adults with no

mental illness. e percentages of adults who used illicit

drugs in the past year were higher among those with SMI

(49.4 percent) and adults with AMI (36.7 percent) compared

with those without any mental illness (15.7 percent).

Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior among Adults

In 2018, an estimated 10.7 million adults aged 18 or

older had thought seriously about trying to kill themselves

(4.3 percent of adults), 3.3 million had made suicide plans

(1.3 percent), and 1.4 million made a nonfatal suicide

attempt (0.6 percent). e percentage of adults aged 18

or older in 2018 who had serious thoughts of suicide was

higher than the percentages in 2008 to 2014, but it was

similar to the percentages in 2015 to 2017. e percentage

of young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2018 with serious thoughts

of suicide also was higher than in 2008 to 2016. Similarly,

the percentage of adults aged 26 to 49 in 2018 who had

serious thoughts of suicide was higher than the percentages

in most years between 2008 and 2015. In contrast, the

percentage of adults aged 50 or older in 2018 with serious

thoughts of suicide was similar to the percentages in most

years from 2008 to 2017.

Substance Use Treatment

In 2018, an estimated 21.2 million people aged 12 or older

needed substance use treatment.

5

is number translates to

about 1 in 13 people who needed treatment (7.8 percent).

About 1 in 26 adolescents aged 12 to 17 (3.8 percent),

about 1 in 7 young adults aged 18 to 25 (15.3 percent),

and 1 in 14 adults aged 26 or older (7.0 percent) needed

treatment. e 2018 percentage of adolescents aged 12 to

17 who needed treatment was lower than in 2015 and 2016,

but it was similar to the percentage in 2017. In contrast,

percentages of adults in 2018 who needed substance use

treatment were similar to the percentages in 2015 to 2017

for young adults aged 18 to 25 and adults aged 26 or older.

In 2018, approximately 1.4 percent of people aged 12

or older (3.7 million people) received any substance use

treatment in the past year, and 0.9 percent (2.4 million)

received substance use treatment at a specialty facility. e

percentages of people aged 12 or older in 2018 who received

any substance use treatment and who received substance

use treatment at a specialty facility were similar to the

percentages in 2015 to 2017. An estimated 11.1 percent of

people aged 12 or older who needed substance use treatment

received treatment at a specialty facility in the past year. e

percentage of people aged 12 or older in 2018 who needed

substance use treatment and received treatment at a specialty

facility also was similar to the percentages in 2015 and 2017.

5

For NSDUH, people are defined as needing substance use treatment if they

had an SUD in the past year or they received substance use treatment at

a specialty facility in the past year. Substance use treatment at a specialty

facility refers to treatment at a hospital (only as an inpatient), a drug or

alcohol rehabilitation facility (as an inpatient or outpatient), or a mental

health center.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health4

|

August 2019

In 2018, among the estimated 18.9 million people aged 12

or older who needed substance use treatment but did not

receive specialty treatment in the past year, about 964,000

perceived a need for substance use treatment. About 2 in

5 people who needed and perceived a need for treatment

but did not receive treatment at a specialty facility were not

ready to stop using, and about 1 in 3 had no health care

coverage and were not able to afford the cost.

Treatment for Depression

Among the 3.5 million adolescents aged 12 to 17 and the

4.6 million young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2018 who had

a past year MDE, 1.4 million adolescents (41.4 percent)

and 2.3 million young adults (49.6 percent) received

treatment for depression. e percentages of adolescents and

young adults in 2018 with a past year MDE who received

treatment for their depression were similar to the percentages

in most prior years.

Mental Health Service Use among Adults

In 2018, an estimated 37.1 million adults aged 18 or older

(15.0 percent of adults) received mental health care during the

past 12 months. Among the 47.6 million adults with AMI,

20.6 million (43.3 percent) received mental health services in

the past year. e percentage of adults in 2018 with AMI who

received mental health care was higher than the percentages

in most years from 2008 to 2012, but it was similar to the

percentages in 2013 to 2017. About 7.3 million of the

11.4 million adults with past year SMI (64.1 percent) received

mental health services in the past year. e percentage of

adults in 2018 with SMI who received mental health care was

similar to the percentages in 2008 to 2012 and 2015 to 2017,

but it was lower than the percentages in 2013 and 2014.

However, about one third of adults with SMI in any given

year did not receive mental health services.

In 2018, an estimated 11.2 million adults aged 18 or older

with past year AMI and 5.1 million adults with past year

SMI had a perceived unmet need for mental health care at

any time in the past year. e percentage of adults in 2018

with AMI who perceived an unmet need for mental health

care in the past year was higher than the percentages in most

years from 2008 to 2017. e percentage of adults in 2018

with SMI who perceived an unmet need for mental health

care in the past year was higher than the percentages in 2015

and 2016, but it was similar to the percentages in 2017 and

in most years from 2008 to 2014. In 2018, about 2 out of 5

adults with AMI (45.2 percent) and slightly more than half

of those with SMI (54.7 percent) who perceived an unmet

need for mental health services did not receive services

because they could not afford the cost of care.

Receipt of Services among People with Co‑Occurring

Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorder

In 2018, among adolescents aged 12 to 17 who had

a co-occurring MDE and an SUD in the past year,

65.7 percent received either substance use treatment at a

specialty facility or mental health services in the past year.

An estimated 5.4 percent of adolescents with a co-occurring

MDE and an SUD received both mental health care and

specialty substance use treatment, 59.5 percent received only

mental health care, and 0.8 percent received only specialty

substance use treatment.

In 2018, about half of the adults aged 18 or older

with co-occurring AMI and an SUD in the past year

(51.4 percent) received either mental health care or specialty

substance use treatment, and 48.6 percent received neither

type of care. An estimated 69.5 percent of adults with

co-occurring SMI and an SUD received either type of care,

and about 1 in 3 (30.5 percent) received neither type of care.

e percentage of adults in 2018 with co-occurring AMI

and an SUD who received mental health care or specialty

substance use treatment was similar to the percentages in all

years from 2015 to 2017. For adults with SMI and an SUD,

the percentage of those who received either type of care was

higher than the percentage in 2015, but it was similar to the

percentages in 2016 and 2017.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health August 2019

|

5

Introduction

Substance use and mental health issues affect millions of

adolescents and adults in the United States and contribute

heavily to the burden of disease in the nation.

1,2,3,4

e

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) is the

primary source for statistical information on illicit drug use,

alcohol use, substance use disorders (SUDs), and mental

health issues for the civilian, noninstitutionalized population

of the United States. Information on mental health and

substance use allows the Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration (SAMHSA) and other policymakers

to gauge progress toward improving the health of the nation.

is report summarizes findings for key substance use

and mental health indicators from the 2018 National

Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

is report contains findings from the 2018 NSDUH for

key substance use and mental health indicators in the United

States. Comprehensive 2018 NSDUH detailed tables showing

additional substance use and mental health-related outcomes,

including data for various subpopulations covered in NSDUH,

are available separately at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

.

5

Survey Background

NSDUH is an annual survey of the civilian, noninstitution-

alized population of the United States aged 12 or older.

6

e survey is sponsored by SAMHSA within the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). e

survey covers residents of households and individuals in

noninstitutional group quarters (e.g., shelters, boarding

houses, college dormitories, migratory workers’ camps,

halfway houses). e survey excludes people with no

fixed address (e.g., people who are homeless and not in

shelters), military personnel on active duty, and residents of

institutional group quarters, such as jails, nursing homes,

mental institutions, and long-term care hospitals.

NSDUH employs a stratified multistage area probability

sample designed to be representative of both the nation as

a whole and for each of the 50 states and the District of

Columbia. e 2018 NSDUH annual target sample size of

67,500 interviews was distributed across three age groups,

with 25 percent allocated to adolescents aged 12 to 17,

25 percent allocated to young adults aged 18 to 25, and

50 percent allocated to adults aged 26 or older.

7

NSDUH is a face-to-face household interview survey

conducted in two phases: the screening phase and the

interview phase. e interviewer conducts a screening

of the sampled household with an adult resident (aged

18 or older) in order to determine whether zero, one, or

two residents aged 12 or older should be selected for the

interview. NSDUH collects data using audio computer-

assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) in which respondents read

or listen to the questions on headphones, then enter their

answers directly into a NSDUH laptop computer. ACASI is

designed for accurate reporting of information by providing

respondents with a highly private and confidential mode for

responding to questions about illicit drug use, mental health,

and other sensitive behaviors. NSDUH also uses computer-

assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) in which interviewers

read less sensitive questions to respondents and enter the

respondents’ answers into a NSDUH laptop computer.

is report is based on data from

67,791 completed interviews from 2018 NSDUH

respondents aged 12 or older.

In 2018, screening was completed at 141,879 addresses,

and 67,791 completed interviews were obtained, including

16,852 interviews from adolescents aged 12 to 17 and

50,939 interviews from adults aged 18 or older. Weighted

response rates for household screening and for interviewing

were 73.3 and 66.6 percent, respectively, for an overall

response rate of 48.8 percent for people aged 12 or older.

e weighted interview response rates were 73.9 percent

for adolescents and 65.8 percent for adults.

8

Further details

about the 2018 NSDUH design and methods can be found

on the web at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

.

9

Data Presentation and Interpretation

is report focuses on substance use and mental health in

the United States based on NSDUH data from 2018 and

earlier years.

10

Estimates of substance use and substance

use treatment are presented for people aged 12 or older,

adolescents, and adults.

11

However, estimates of mental

health issues and mental health service use are not presented

jointly for people aged 12 or older. Rather, these estimates

are presented separately for adolescents aged 12 to 17 and

adults aged 18 or older because adolescents and adults

completed different sets of questions regarding mental

health and mental health service utilization. All estimates

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health6

|

August 2019

(e.g., percentages and numbers) presented in the report are

derived from survey data that are subject to sampling errors.

e estimates have met the criteria for statistical precision.

Estimates not meeting these criteria have been suppressed

and are not shown.

12

One of NSDUH’s strengths is the stability in the sample

and survey design. is stability allows for the examination

of trends across time. However, the benefit of using

NSDUH data to assess trends has to be balanced with the

periodic need to revise or add content to address changes in

society and emerging issues.

13

Consequently, the number

of years for which comparisons can be made varies across

measures depending on when content was revised or added

for NSDUH. For example, the perceived recovery items

were added in 2018; as a result, these items will establish a

baseline that starts in 2018 (

Table A.4 in Appendix A). e

prescription drug misuse items revised in 2015 have 4 years of

trend data for 2015 to 2018 (Table A.1B), and the marijuana

use items have 17 years of trend data for 2002 to 2018

(Table A.1B). All trends in the report present 2018 estimates

and comparable estimates from 3 or more prior years.

Most trend analyses are presented for percentages because

the percentages take into account any change in the size

of the total population and facilitate the comparison of

estimates across years.

14

However, trend analyses for the

initiation of substance use present the number of people

who initiated substance use in the past year rather than

percentages. erefore, care should be taken in interpreting

increases over time in the estimated number of past year

initiates because some of these increases could reflect growth

in the size of the population. Percentages of the population

who initiated substance use in the past year are available in

the 2018 NSDUH detailed tables, such as Detailed Table

(DT) 4.4 at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/.

Analyses of trends in this report focus on long‑term trends

in substance use and mental health issues. Trends for

2015 to 2018 also are presented for selected measures.

Statistical tests have been conducted for comparisons

appearing in the text of the report. Statistically significant

differences are described using terms such as “higher,” “lower,”

“increased,” or “decreased.” Statements use terms such as

“similar,” “remained steady,” or “stable” when a difference is

not statistically significant. Analyses of long-term trends in

this report involving more than 4 years of data summarize

whether the 2018 estimates differ from or are similar to

estimates in most or all previous years,

15

while minimizing

discussion of anomalous differences between any 2 years that

can occur due to these estimates being based on samples.

16

Substance Use in the Past Month

Tobacco products, alcohol, and illicit drugs are the three

categories of substances measured in NSDUH. is section

provides an overview of whether respondents aged 12 or

older have used any of these substances in the 30 days

before the interview (i.e., in the past month, also referred to

as “current use”). Additional details on the use of tobacco

products, alcohol, and illicit drugs are provided in other

sections of this report.

Past month tobacco use includes any use of the four

tobacco products in NSDUH: cigarettes, smokeless tobacco

(such as snuff, dip, chewing tobacco, or snus), cigars, and

pipe tobacco.

17

Alcohol use in the past month refers to

having more than a sip or two from any type of alcoholic

drink (e.g., can or bottle of beer, a glass of wine or a wine

cooler, a shot of liquor, or a mixed drink with liquor in it).

In NSDUH, illicit drug use in the past month includes

any use of marijuana, cocaine (including crack), heroin,

hallucinogens, inhalants, or methamphetamine, as well as

misuse of prescription stimulants, tranquilizers or sedatives

(including benzodiazepines), or pain relievers. (See the

section on the Misuse of Psychotherapeutic Drugs for the

definition of “misuse.”)

In 2018, an estimated 164.8 million people aged 12 or older

used a substance (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, or an illicit drug) in

the past month (Figure 1). is number of current substance

users corresponds to 60.2 percent of the population. About

2 out of 5 people aged 12 or older (108.9 million, or

39.8 percent) did not use substances in the past month.

e 164.8 million current substance users in 2018 include

139.8 million people who drank alcohol, 58.8 million

people who used a tobacco product, and 31.9 million people

who used an illicit drug (2018 DT 7.3). ese numbers are

not mutually exclusive because respondents could have used

more than one type of substance (e.g., tobacco products and

alcohol) in the past month.

Although about half of the people aged 12 or older

(51.1 percent) drank alcohol in the past month and 1

in 5 (21.5 percent) used a tobacco product, use of illicit

drugs was less common (Table A.1B). About 1 in 9 people

aged 12 or older (11.7 percent) used an illicit drug in the

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health August 2019

|

7

past month. Given that illicit drug use was less prevalent

than the use of either tobacco or alcohol, the remainder of

this report presents past year estimates of illicit drug use to

allow presentation of estimates for low prevalence drugs,

such as heroin. In contrast, the higher prevalence of tobacco

and alcohol use makes it possible to present estimates not

only for any past month use of these substances, but also

for the intensity of their use in the past month (e.g., daily

cigarette use, binge alcohol use).

Tobacco Use in the Past Month

NSDUH data can be used to estimate the percentage of

people who currently use tobacco products and to monitor

changes in tobacco use over time. As noted in the section on

Substance Use in the Past Month, NSDUH asks respondents

aged 12 or older about their tobacco use in the 30 days

before the interview. Tobacco products include cigarettes,

smokeless tobacco (such as snuff, dip, chewing tobacco, or

snus), cigars, and pipe tobacco.

17

Cigarette use is defined

as smoking “part or all of a cigarette.” A discussion of the

estimates for daily cigarette smoking follows a presentation

of the estimates for any cigarette smoking in the past month.

e majority of the 58.8 million current (i.e., past month)

tobacco users in 2018 were current cigarette smokers (Figure 2),

as has been the case historically.

18

Specifically, 47.0 million

people aged 12 or older in 2018 were current cigarette smokers,

12.2 million people were current cigar smokers, 8.0 million

people were current users of smokeless tobacco, and 2.1 million

people currently smoked pipe tobacco.

Among current users of any tobacco product who were aged

12 or older, 65.5 percent smoked cigarettes but did not use

other tobacco products, 14.4 percent smoked cigarettes and

used some other type of tobacco product, and 20.1 percent

used other tobacco products but not cigarettes (Table A.2B).

is same pattern was observed in 2018 among young adults

aged 18 to 25 and adults aged 26 or older, with most current

tobacco users smoking only cigarettes. Specifically, more than

half of young adults (50.3 percent) and more than two thirds

of adults aged 26 or older (68.9 percent) who were current

tobacco users smoked only cigarettes in the past month.

Among adults who were current users of tobacco products,

25.9 percent of those aged 18 to 25 and 18.7 percent of those

aged 26 or older did not smoke cigarettes. In contrast, among

adolescents who were current tobacco users, 36.1 percent

used tobacco products other than cigarettes but did not

smoke cigarettes. In addition, 26.5 percent of adolescents and

23.8 percent of young adults aged 18 to 25 who were current

tobacco users smoked cigarettes and used other tobacco

products. Among adults aged 26 or older who were current

tobacco users, about 1 in 8 (12.4 percent) were current

cigarette smokers and current users of other tobacco products.

e remainder of this section on tobacco use focuses on

cigarette smoking because most current tobacco users were

cigarette smokers. More information on the use of cigars,

pipe tobacco, and smokeless tobacco in the past month by

people aged 12 or older can be found in Table A.1B and

in the 2018 detailed tables by age groups (i.e., DT 7.6,

DT 7.12, and DT 7.15, respectively).

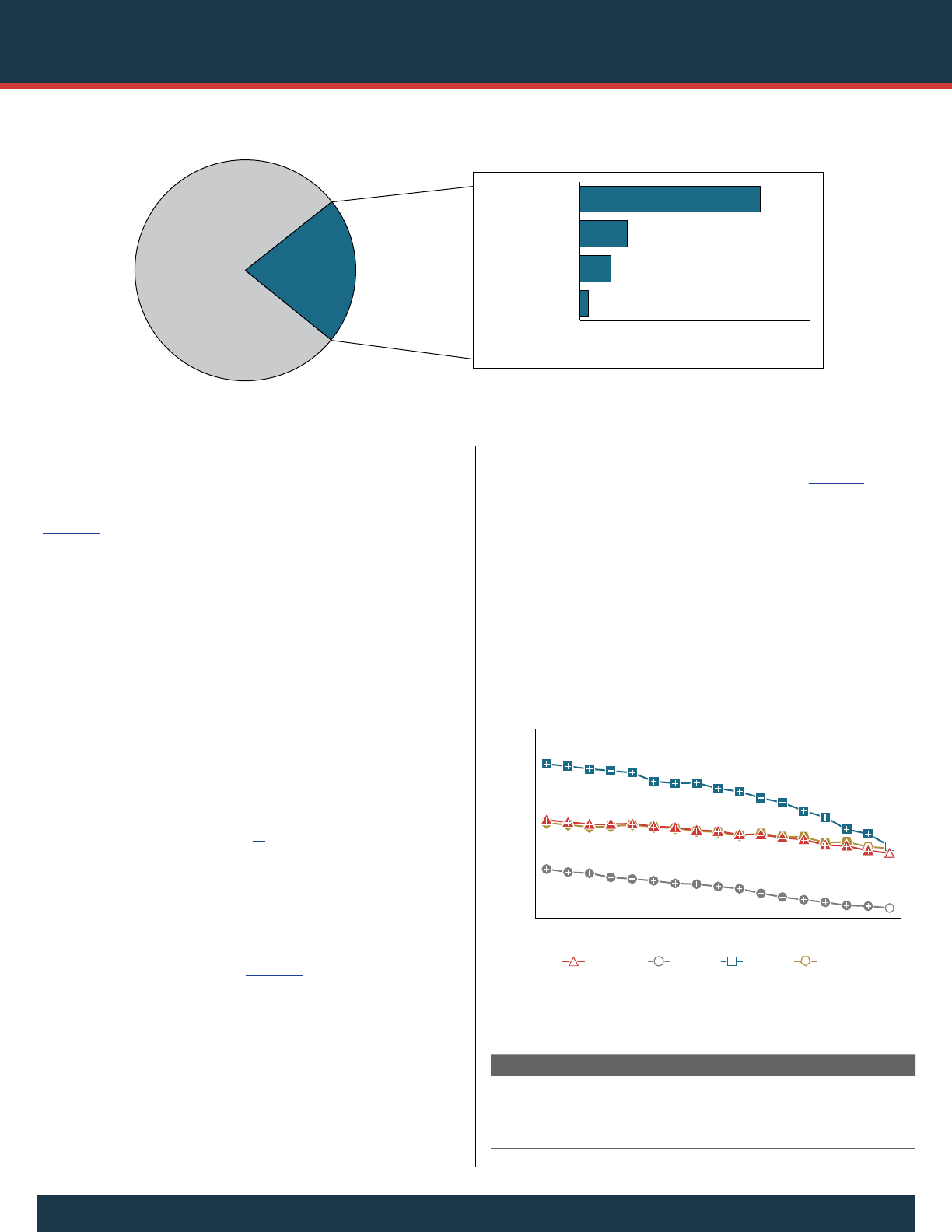

Figure 1. Past Month Substance Use among People Aged 12 or Older: 2018

139.8M

58.8M

27.7M

2.9M

1.9M

1.8M

1.7M

1.6M

1.0M

612,000

354,000

0 50 100 150

Alcohol

Tobacco

Marijuana

Rx Pain Reliever Misuse

Cocaine

Rx Tranquilizer or Sedative Misuse

Rx Stimulant Misuse

Hallucinogens

Methamphetamine

Inhalants

Heroin

Number of Past Month Users

Past Month

Substance Use

164.8 Million People

(60.2%)

No Past Month

Substance Use

108.9 Million People

(39.8%)

Rx = prescription.

Note: The estimated numbers of current users of different substances are not mutually exclusive because people could have used more than one type of substance in the past month.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health8

|

August 2019

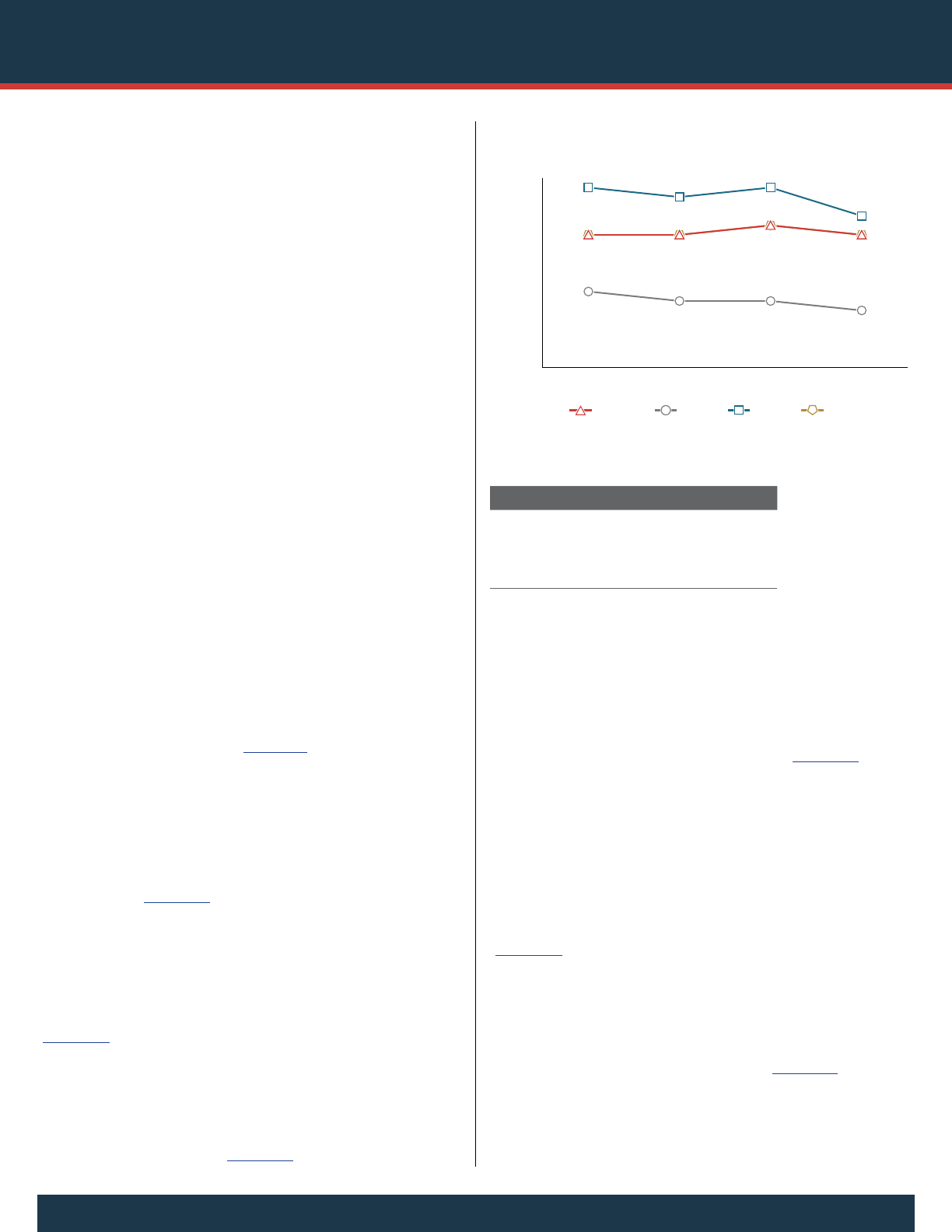

Cigarette Use

As noted previously, an estimated 47.0 million people

aged 12 or older in 2018 were current cigarette smokers

(Figure 2). is number of current cigarette smokers

correspond to 17.2 percent of the population (Figure 3). e

percentage of the population who smoked cigarettes in the

past month was lower in 2018 than in 2002 to 2017. Stated

another way, fewer than 1 in 6 people aged 12 or older in

2018 were current cigarette smokers. In comparison, about 1

in 4 people were current cigarette smokers in 2002 to 2008

(ranging from 24.0 to 26.0 percent).

Although cigarette smoking declined, some of this decline

may reflect a rise in the use of electronic vaporizing devices

(“vaping”), such as e-cigarettes, as a substitute for delivering

nicotine. NSDUH does not currently ask separate questions

about the vaping of nicotine. e measurement of both

cigarette use and the vaping of nicotine may be needed to

understand tobacco use trends.

19

Aged 12 to 17

In 2018, an estimated 672,000 adolescents aged 12 to

17 smoked cigarettes in the past month. is number of

adolescents who were current cigarette smokers corresponds

to 2.7 percent of adolescents (Figure 3). e percentage of

adolescents who were past month cigarette smokers declined

from 13.0 percent in 2002 (or about 1 in 8 adolescents) to

2.7 percent in 2018 (or about 1 in 37). e percentage of

adolescents who were current cigarette smokers in 2018 was

lower than the percentages in each year from 2002 to 2017.

Aged 18 to 25

In 2018, an estimated 6.5 million young adults aged 18 to 25

smoked cigarettes in the past month. is number of young

adults who were current cigarette smokers corresponds to

about one fifth of young adults (19.1 percent) (Figure 3). e

percentage of young adults who were current cigarette smokers

in 2018 was lower than the percentages in 2002 to 2017.

Aged 26 or Older

In 2018, an estimated 39.8 million adults aged 26 or older

smoked cigarettes in the past month. Stated another way,

about 1 in 5 adults aged 26 or older (18.5 percent) were

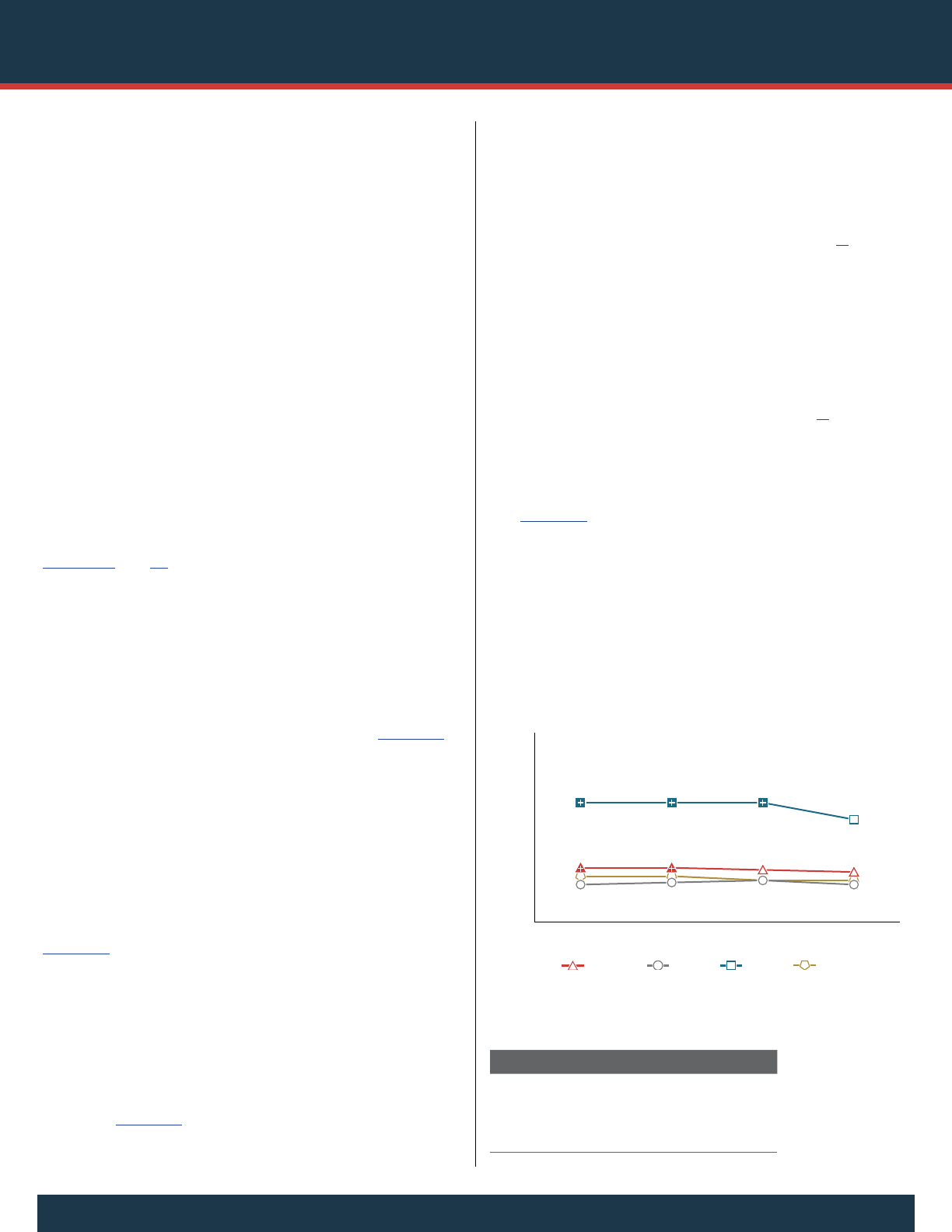

Figure 3. Past Month Cigarette Use among People Aged 12 or

Older: 2002-2018

Percent Using in Past Month

0

10

20

30

40

50

1817161514131211100908070605040302

12 or Older 12 to 17 18 to 25 26 or Older

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 3 Table. Past Month Cigarette Use among People Aged 12 or Older:

2002-2018

Age 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

≥12

26.0

+

25.4

+

24.9

+

24.9

+

25.0

+

24.3

+

24.0

+

23.3

+

23.0

+

22.1

+

22.1

+

21.3

+

20.8

+

19.4

+

19.1

+

17.9

+

17.2

12-17

13.0

+

12.2

+

11.9

+

10.8

+

10.4

+

9.9

+

9.2

+

9.0

+

8.4

+

7.8

+

6.6

+

5.6

+

4.9

+

4.2

+

3.4

+

3.2

+

2.7

18-25

40.8

+

40.2

+

39.5

+

39.0

+

38.5

+

36.2

+

35.7

+

35.8

+

34.3

+

33.5

+

31.8

+

30.6

+

28.4

+

26.7

+

23.5

+

22.3

+

19.1

≥26

25.2

+

24.7

+

24.1

+

24.3

+

24.7

+

24.1

+

23.8

+

23.0

+

22.8

+

21.9

+

22.4

+

21.6

+

21.5

+

20.0

+

20.2

+

18.9 18.5

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 2. Past Month Tobacco Use among People Aged 12 or Older: 2018

47.0M

12.2M

8.0M

2.1M

0 20 40 60

Cigarettes

Cigars

Smokeless Tobacco

Pipe Tobacco

Number of Past Month Users

Past Month

Tobacco Use

58.8 Million People

(21.5%)

No Past Month

Tobacco Use

215.0 Million People

(78.5%)

Note: The estimated numbers of current users of different tobacco products are not mutually exclusive because people could have used more than one type of tobacco

product in the past month.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health August 2019

|

9

current cigarette smokers in 2018 (Figure 3). e 2018

estimate for current cigarette smoking among adults aged 26

or older was lower than the estimates from 2002 to 2016,

but it was similar to the 2017 estimate.

Daily Cigarette Use

Among the 47.0 million current cigarette smokers aged 12

or older in 2018, 27.3 million were daily cigarette smokers.

e 27.3 million daily smokers correspond to 58.2 percent

of current cigarette smokers (Figure 4). us, nearly three

fifths of current cigarette smokers in 2018 smoked cigarettes

daily. e percentage of current smokers in 2018 who

smoked cigarettes daily was lower than the percentages in

most years from 2002 to 2012, but it was similar to the

percentages in 2013 to 2017 (2018 DT 7.26).

Among the 27.3 million daily smokers aged 12 or older

in 2018, 10.8 million smoked 16 or more cigarettes per

day (i.e., approximately one pack or more per day). Stated

another way, about 2 out of 5 daily smokers (39.6 percent)

smoked a pack or more of cigarettes per day (Figures 4 and

5). e percentage of daily smokers who smoked one or more

packs of cigarettes per day was lower in 2018 than in 2002 to

2011, but it was similar to the percentages in 2012 to 2017.

Aged 12 to 17

In 2018, about 99,000 adolescents aged 12 to 17 smoked

cigarettes every day in the past month. is number corresponds

to about 1 in 7 adolescent current smokers (14.7 percent) (2018

DT 7.27). e 2018 percentage was lower than the percentages

in most years from 2002 to 2014, but it was similar to the

percentages in 2015 to 2017. e percentage of adolescent

daily smokers who smoked one or more packs of cigarettes per

day was not reported for 2018 due to low precision.

12

Aged 18 to 25

About 2.4 million young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2018 were

daily cigarette smokers in the past month, or 37.4 percent

of young adults who were current cigarette smokers (2018

DT 7.29). us, nearly 2 in 5 young adults in 2018 who were

current cigarette users smoked cigarettes daily. e percentage

of young adult current smokers in 2018 who smoked

Figure 5. Smokers of One or More Packs of Cigarettes per Day

among Past Month Daily Cigarette Smokers Aged 12 or Older:

2002-2018

Percent Using in Past Month

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

1817161514131211100908070605040302

12 or Older 12 to 17 18 to 25 26 or Older

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 5 Table. Smokers of One or More Packs of Cigarettes per Day among

Past Month Daily Cigarette Smokers Aged 12 or Older: 2002-2018

Age 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

≥12

53.1

+

53.5

+

54.0

+

51.4

+

50.6

+

50.9

+

49.2

+

45.9

+

45.1

+

43.8

+

42.0 41.3 40.3 41.1 41.1 41.2 39.6

12-17

21.8 22.0 19.4 20.1 17.9 18.7 18.4 17.9 16.7 14.8 10.8 11.9 11.9 7.8 * * *

18-25

39.1

+

37.1

+

34.9

+

36.9

+

34.4

+

32.9

+

31.6

+

29.5

+

27.3

+

26.1 25.1 22.3 22.5 22.5 26.2 25.0 23.4

≥26

57.1

+

58.0

+

59.2

+

55.1

+

54.5

+

55.1

+

53.0

+

49.4

+

48.8

+

47.4

+

45.2

+

44.7

+

43.3 44.1 43.1 43.2 41.4

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

* Low precision; no estimate reported.

Figure 4. Daily Cigarette Use among Past Month Cigarette Smokers Aged 12 or Older and

Smoking of One or More Packs of Cigarettes per Day among Current Daily Smokers: 2018

16.4 Million

Smokers of

Less Than a

Pack per Day

(60.4%)

10.8 Million

Smokers of

One or More

Packs per Day

(39.6%)

19.6 Million

Less Than

Daily Smokers

(41.8%)

27.3 Million

Daily Smokers

(58.2%)

Note: Current daily smokers with unknown data about the number of cigarettes smoked per day were excluded from the pie graph on the right.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health10

|

August 2019

cigarettes daily was lower than the percentages in 2002 to

2015, but it was similar to the percentages in 2016 and 2017.

e percentage of young adult daily smokers in 2018 who

smoked one or more packs of cigarettes per day (23.4 percent)

was lower than the percentages in 2002 to 2010, but it was

similar to the percentages in 2011 to 2017 (Figure 5).

Aged 26 or Older

In 2018, about 24.8 million adults aged 26 or older smoked

cigarettes every day in the past month, which corresponds to

62.3 percent of the current smokers in this age group (2018

DT 7.30). e percentage of current smokers in this age

group in 2018 who smoked cigarettes every day was lower

than the percentages in 2002 to 2013, but it was similar to

the percentages in 2014 to 2017. Despite the decline since

2002, when nearly 70 percent of current smokers aged 26 or

older were daily smokers, about three fifths of current smokers

in this age group in 2018 were daily smokers. Among daily

smokers aged 26 or older, the percentage in 2018 who smoked

one or more packs of cigarettes per day (41.4 percent) was

lower than in 2002 to 2013. However, the percentage was

stable from 2014 to 2018 (Figure 5).

Alcohol Use in the Past Month

As noted in the section on Substance Use in the Past Month,

NSDUH asks respondents aged 12 or older about their

alcohol use in the 30 days before the interview. Current

alcohol use is defined as any use of alcohol in the

past 30 days. In addition to asking about any alcohol use,

NSDUH collects information on binge alcohol use and

heavy alcohol use. Binge drinking for males is defined as

drinking five or more drinks

20

on the same occasion on at

least 1 day in the past 30 days, which is unchanged from the

threshold prior to 2015. Since 2015, binge alcohol use for

females has been defined as drinking four or more drinks

on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days.

21

is definition of binge alcohol use is consistent with

federal definitions.

22

Heavy alcohol use is defined as binge

drinking on 5 or more days in the past 30 days based on

the thresholds described previously for males and females.

Any alcohol use, binge drinking, and heavy drinking are not

mutually exclusive categories of use; heavy use is included in

estimates of binge and current use, and binge use is included

in estimates of current use (

Figure 6).

In 2018, an estimated 139.8 million Americans aged 12 or older

were current alcohol users, 67.1 million were binge drinkers

in the past month, and 16.6 million were heavy drinkers in

the past month (Figure 6). us, nearly half of current alcohol

users were binge drinkers (48.0 percent), and 1 in 8 current

alcohol users were heavy drinkers (11.8 percent). Among binge

drinkers, about 1 in 4 (24.7 percent) were heavy drinkers.

23

Any Alcohol Use

e estimate of 139.8 million current alcohol users aged 12

or older in 2018 (Figure 6) corresponds to past month use

by slightly more than half of the people in the population

(51.1 percent) (Figure 7). e 2018 estimate of past month

alcohol use was similar to the estimates in most years from

2002 to 2017.

Aged 12 to 17

An estimated 9.0 percent of adolescents aged 12 to 17

in 2018 were current alcohol users (Figure 7), which

corresponds to 2.2 million adolescents who drank alcohol

in the past month. e percentage of adolescents who were

current alcohol users in 2018 was lower than the percentages

in most years from 2002 through 2017. Although the

estimate of current alcohol use among adolescents decreased

between 2002 and 2018, about 1 in 11 adolescents were

current alcohol users in 2018.

Aged 18 to 25

In 2018, an estimated 55.1 percent of young adults aged 18

to 25 were current alcohol users (Figure 7), which corresponds

to about 18.8 million young adults. e percentage of young

adults in 2018 who drank alcohol in the past month was

lower than the percentages in 2002 through 2016, but it was

similar to the percentage in 2017. In addition, more than half

of young adults were current alcohol users in each year from

2002 to 2018 (ranging from 55.1 to 62.0 percent).

Figure 6. Current, Binge, and Heavy Alcohol Use among People

Aged 12 or Older: 2018

139.8 Million

Alcohol Users

67.1 Million

Binge Alcohol Users

(48.0% of Alcohol Users)

16.6 Million

Heavy Alcohol Users

(24.7% of Binge Alcohol

Users and 11.8% of

Alcohol Users)

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health August 2019

|

11

Aged 26 or Older

More than half of adults aged 26 or older in 2018 (55.3 percent)

were current alcohol users (Figure 7). is percentage

corresponds to about 118.8 million adults in this age group who

drank alcohol in the past month. In each year between 2002 and

2018, slightly more than half of adults aged 26 or older were

current alcohol users (ranging from 52.5 to 56.5 percent).

Binge Alcohol Use

In 2018, about 1 in 4 people aged 12 or older (24.5 percent)

were current binge alcohol users (Figure 8). is percentage

corresponds to about 67.1 million binge drinkers who were

aged 12 or older (Figure 6). e percentage of the population

who were past month binge alcohol users was stable from

2015 to 2018 (ranging from 24.2 to 24.9 percent).

Aged 12 to 17

About 1.2 million adolescents aged 12 to 17 in 2018 were

past month binge drinkers, which corresponds to 4.7 percent

of adolescents (Figure 8). us, about 1 in 21 adolescents

were current binge drinkers. e percentage of adolescents

who were current binge drinkers in 2018 was similar to the

percentages in 2016 and 2017, but it was lower than the

percentage in 2015 (5.8 percent).

Aged 18 to 25

An estimated 34.9 percent of young adults aged 18 to 25

in 2018 were binge drinkers in the past month (Figure 8),

which corresponds to about 11.9 million young adults. Stated

another way, more than a third of young adults in 2018

were current binge drinkers. Nevertheless, the percentage of

young adults who were current binge drinkers in 2018 was

lower than the percentages in 2015 to 2017 (ranging from

39.0 percent in 2015 to 36.9 percent in 2017).

Aged 26 or Older

In 2018, about a quarter (25.1 percent) of adults aged 26 or

older were current binge drinkers (Figure 8). is percentage

corresponds to about 54.0 million adults in this age group

who were binge drinkers. e percentage of adults aged

26 or older who were current binge drinkers in 2018 was

higher than the percentage in 2016, but it was similar to the

percentages in 2015 and 2017.

Heavy Alcohol Use

e estimate of 16.6 million people aged 12 or older in 2018

who were heavy alcohol users in the past month (Figure 6)

corresponds to 6.1 percent of the population (Figure 9). e

percentage of people who were current heavy alcohol users in

Figure 7. Past Month Alcohol Use among People Aged 12 or Older:

2002-2018

Percent Using in Past Month

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

1817161514131211100908070605040302

12 or Older 12 to 17 18 to 25 26 or Older

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 7 Table. Past Month Alcohol Use among People Aged 12 or Older:

2002-2018

Age 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

≥12

51.0 50.1 50.3 51.8 51.0 51.2 51.6 51.9 51.8 51.8 52.1 52.2

+

52.7

+

51.7 50.7 51.7 51.1

12-17

17.6

+

17.7

+

17.6

+

16.5

+

16.7

+

16.0

+

14.7

+

14.8

+

13.6

+

13.3

+

12.9

+

11.6

+

11.5

+

9.6 9.2 9.9

+

9.0

18-25

60.5

+

61.4

+

60.5

+

60.9

+

62.0

+

61.3

+

61.1

+

61.8

+

61.4

+

60.7

+

60.2

+

59.6

+

59.6

+

58.3

+

57.1

+

56.3 55.1

≥26

53.9

+

52.5

+

53.0

+

55.1 53.7

+

54.1 54.7 54.9 54.9 55.1 55.6 55.9 56.5 55.6 54.6 55.8 55.3

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

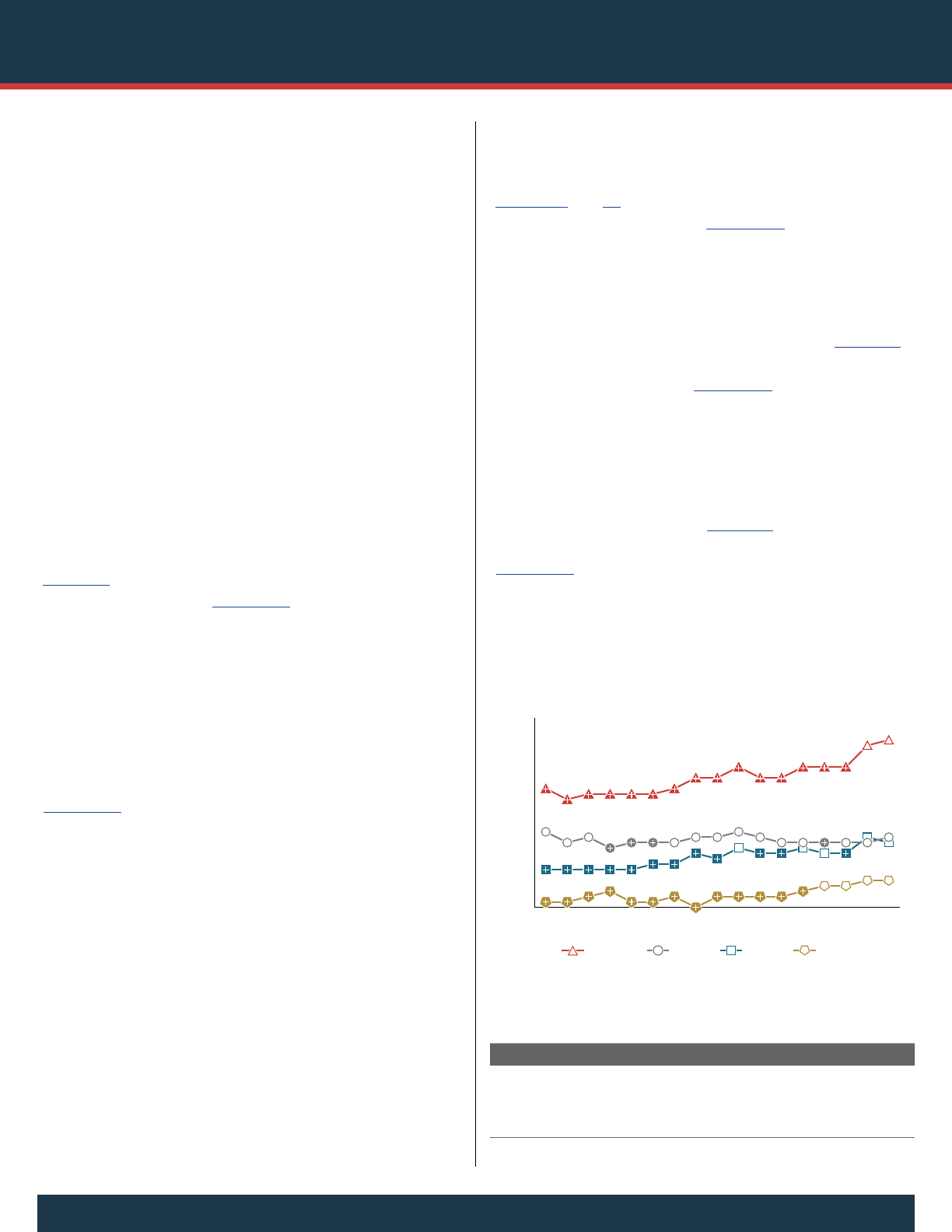

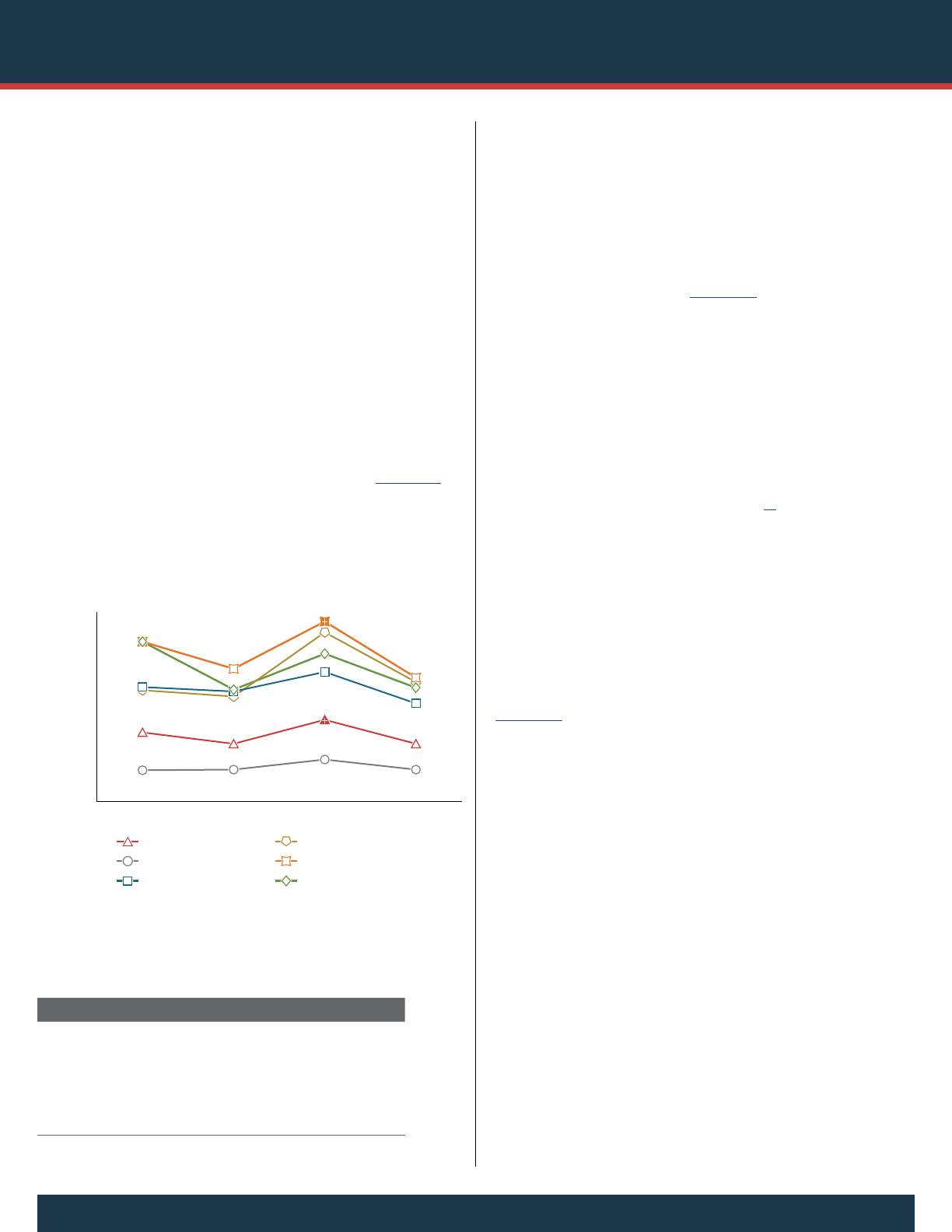

Figure 8. Past Month Binge Alcohol Use among People Aged 12 or

Older: 2015-2018

Percent Using in Past Month

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2018201720162015

12 or Older 12 to 17 18 to 25 26 or Older

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 8 Table. Past Month Binge Alcohol Use among People Aged 12 or

Older: 2015-2018

Age 2015 2016 2017 2018

12 or Older

24.9 24.2 24.5 24.5

12 to 17

5.8

+

4.9 5.3 4.7

18 to 25

39.0

+

38.4

+

36.9

+

34.9

26 or Older

24.8 24.2

+

24.7 25.1

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health12

|

August 2019

2018 was similar to the percentages in 2016 and 2017, but it

was lower than the percentage in 2015 (6.5 percent).

Aged 12 to 17

In 2018, an estimated 131,000 adolescents aged 12 to 17

were current heavy drinkers. Stated another way, about 1 out

of 200 adolescents (0.5 percent) engaged in binge drinking

on 5 or more days in the past 30 days (Figure 9). e

percentage of adolescents who were current heavy drinkers in

2018 was lower than the percentages in 2015 and 2016 but

was similar to the percentage in 2017 (0.7 percent).

Aged 18 to 25

About 1 out of every 11 young adults aged 18 to 25

(9.0 percent) in 2018 was a current heavy alcohol drinker

(Figure 9). is percentage corresponds to 3.1 million young

adults who engaged in heavy drinking in the past month. e

percentage of young adults who were current heavy drinkers

in 2018 was lower than the percentages in 2015 and 2016

but was similar to the percentage in 2017 (9.6 percent).

Aged 26 or Older

An estimated 6.2 percent of adults aged 26 or older in 2018

were current heavy drinkers (Figure 9). is percentage

corresponds to about 13.4 million adults in this age group who

engaged in heavy drinking in the past month. e percentage

of adults aged 26 or older who were current heavy alcohol

users in 2018 was similar to the percentages in 2015 to 2017.

Illicit Drug Use in the PastYear

As noted previously, NSDUH obtains illicit drug

use information for the use of marijuana, cocaine

(including crack), heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, and

methamphetamine, as well as for the misuse of prescription

stimulants, the misuse of tranquilizers or sedatives,

24

and

the misuse of pain relievers (see the section on the Misuse

of Psychotherapeutic Drugs for the definition of “misuse”).

Estimates of “illicit drug use” reported from NSDUH

reflect the data from these drug categories. is report also

describes in later sections the misuse of benzodiazepines and

opioids in the past year (e.g., the misuse of prescription pain

relievers or the use of heroin).

25

Unlike estimates of tobacco and alcohol use, estimates of

illicit drug use are presented for use in the past year rather

than the past month. e presentation of past year estimates

improves the precision of estimates for detecting changes

over time in substances with a low prevalence, such as

heroin. In addition, details on the misuse of benzodiazepines

and specific subtypes of prescription pain relievers (e.g.,

fentanyl products) were collected only for the past year.

Among people aged 12 or older in 2018, an estimated

53.2 million people used illicit drugs in the past year

(Figure 10). e most commonly used illicit drug in the

past year was marijuana, which was used by 43.5 million

people. e second most common type of illicit drug use

in the United States was the misuse of prescription pain

relievers by an estimated 9.9 million people in the past year.

Smaller numbers of people were past year users of the other

illicit drugs, as shown in Figure 10.

26

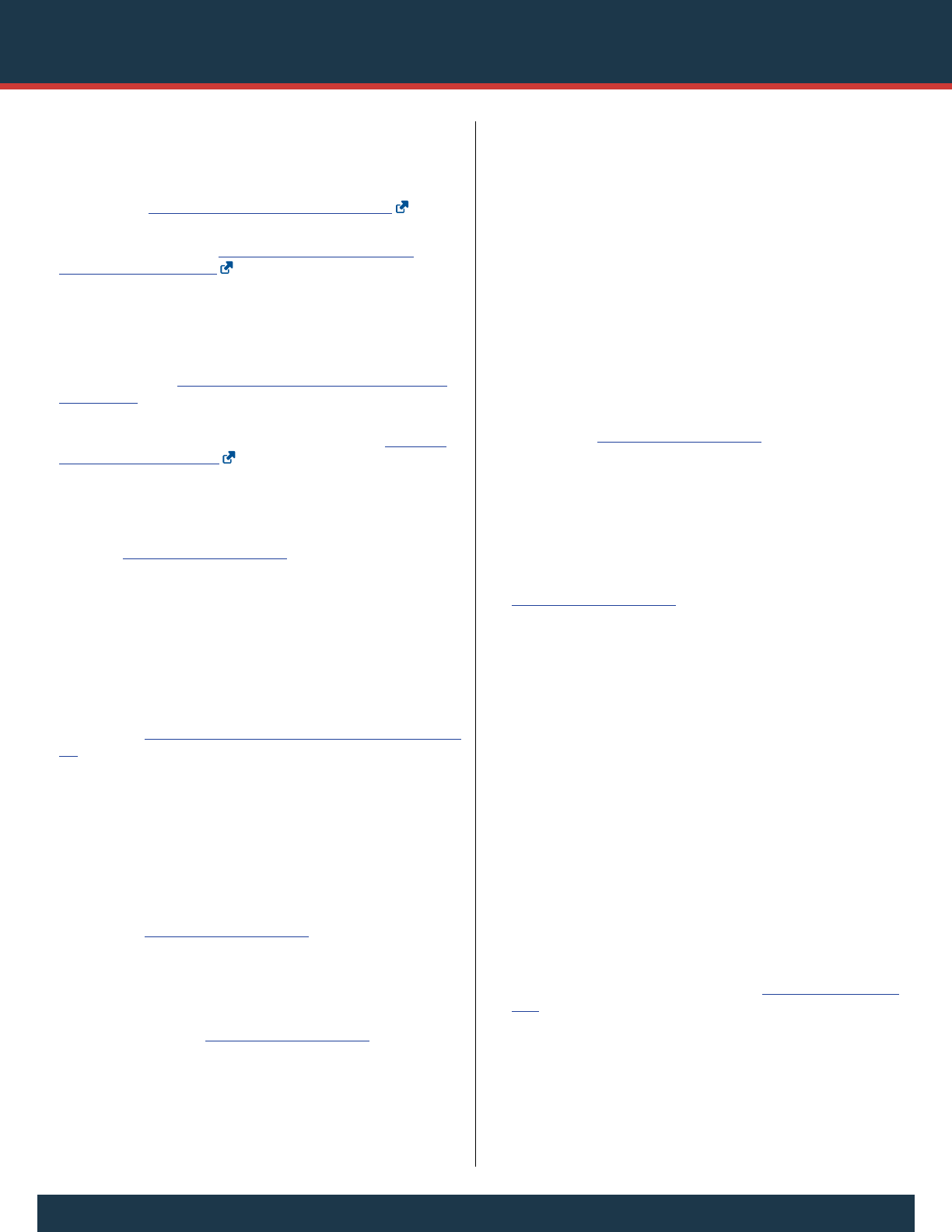

Any Illicit Drug Use

e estimated 53.2 million people aged 12 or older in

2018 who were past year illicit drug users correspond to

19.4 percent of the population (Figures 10 and 11). Stated

another way, nearly 1 in 5 people aged 12 or older in the

United States used illicit drugs in the past year. e percentage

of the population in 2018 who used illicit drugs in the

past year was higher than the percentages in 2015 and 2016

but was similar to the percentage in 2017 (19.0 percent).

Figure 9. Past Month Heavy Alcohol Use among People Aged 12 or

Older: 2015-2018

Percent Using in Past Month

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

2018201720162015

12 or Older 12 to 17 18 to 25 26 or Older

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 9 Table. Past Month Heavy Alcohol Use among People Aged 12 or

Older: 2015-2018

Age 2015 2016 2017 2018

12 or Older

6.5

+

6.0 6.1 6.1

12 to 17

0.9

+

0.8

+

0.7 0.5

18 to 25

10.9

+

10.1

+

9.6 9.0

26 or Older

6.4 6.0 6.2 6.2

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health August 2019

|

13

Aged 12 to 17

Approximately 4.2 million adolescents aged 12 to 17 in

2018 were past year illicit drug users, which corresponds

to about 1 in 6 adolescents (16.7 percent) (Figure 11). e

percentage of adolescents in 2015 to 2018 who used illicit

drugs in the past year ranged from 15.8 to 17.5 percent.

Aged 18 to 25

Approximately 2 in 5 young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2018

(38.7 percent) were past year users of illicit drugs (Figure 11).

is percentage corresponds to about 13.2 million young

adults who used illicit drugs in the past year. e percentage

of young adults in 2018 who used illicit drugs in the

past year was similar to the percentages in 2015 to 2017.

Aged 26 or Older

In 2018, about 1 in 6 adults aged 26 or older (16.7 percent)

were past year users of illicit drugs (Figure 11), or about

35.9 million adults in this age group. e percentage of

adults aged 26 or older in 2018 who were past year illicit

drug users was higher than the percentages in 2015 and 2016

but was similar to the percentage in 2017 (16.1 percent).

Marijuana Use

As noted in the section on Illicit Drug Use in the Past Year, an

estimated 43.5 million Americans aged 12 or older in 2018

used marijuana in the past year (Figure 10). is number of

past year marijuana users corresponds to 15.9 percent of the

population (Figure 12). e percentage of the population in

2018 who used marijuana was higher than the percentages from

2002 to 2017. is increase in marijuana use among people

aged 12 or older reflects increases in marijuana use among

both young adults aged 18 to 25 and adults aged 26 or older.

Aged 12 to 17

In 2018, about 1 in 8 adolescents aged 12 to 17 (12.5 percent)

were past year users of marijuana (Figure 12). is represents

approximately 3.1 million adolescents who used marijuana in

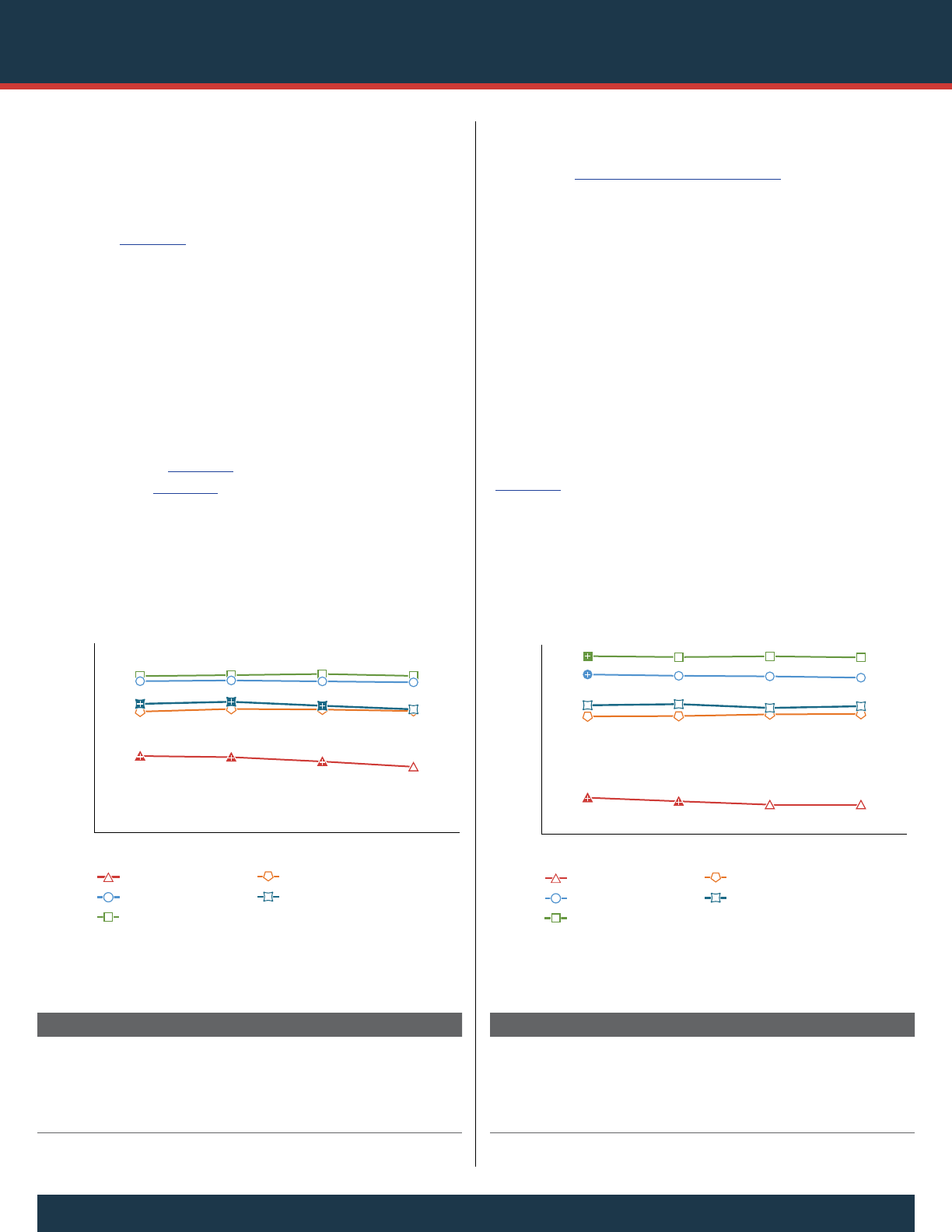

Figure 11. PastYear Illicit Drug Use among People Aged 12 or

Older: 2015-2018

Percent Using in Past Year

0

10

20

30

40

50

2018201720162015

12 or Older 12 to 17 18 to 25 26 or Older

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 11 Table. PastYear Illicit Drug Use among People Aged 12 or Older:

2015-2018

Age 2015 2016 2017 2018

12 or Older

17.8

+

18.0

+

19.0 19.4

12 to 17

17.5 15.8 16.3 16.7

18 to 25

37.5 37.7 39.4 38.7

26 or Older

14.6

+

15.0

+

16.1 16.7

+

Difference between this estimate and the 2018 estimate is statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 10. PastYear Illicit Drug Use among People Aged 12 or Older: 2018

43.5M

9.9M

6.4M

5.6M

5.5M

5.1M

2.0M

1.9M

808,000

0 10 20 30 40 50

Marijuana

Rx Pain Reliever Misuse

Rx Tranquilizer or Sedative Misuse

Hallucinogens

Cocaine

Rx Stimulant Misuse

Inhalants

Methamphetamine

Heroin

Number of Past Year Users

Past Year

Illicit Drug Use

53.2 Million People

(19.4%)

No Past Year

Illicit Drug Use

220.6 Million People

(80.6%)

Rx = prescription.

Note: The estimated numbers of past year users of different illicit drugs are not mutually exclusive because people could have used more than one type of illicit drug in the past year.

Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States:

Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health14

|

August 2019

the past year. e percentage of adolescents in 2018 who used

marijuana in the past year was lower than the percentages in

2002 to 2004 and in 2009 to 2013, but it was similar to the

percentages in 2005 to 2008 and in 2014 to 2017.

Aged 18 to 25

In 2018, more than a third of young adults aged 18 to 25

(34.8 percent) were past year users of marijuana (Figure 12),

or about 11.8 million young adults. e percentage of young

adults in 2018 who were past year marijuana users was

higher than the percentages between 2002 and 2016, but it

was similar to the percentage in 2017.

Aged 26 or Older

In 2018, an estimated 13.3 percent of adults aged 26 or older

were past year users of marijuana (Figure 12), which represents

about 28.5 million adults in this age group. e percentage

of adults aged 26 or older in 2018 who used marijuana in the

past year was higher than the percentages in 2002 to 2017.

Cocaine Use

In this report, estimates of the use of cocaine include use

of crack cocaine. Estimates also are presented separately for

crack use.

In 2018, an estimated 5.5 million people aged 12 or older

were past year users of cocaine (Figure 10), including

about 757,000 users of crack. Stated another way, about

2.0 percent of the population in 2018 used cocaine

(Figure 13), and 0.3 percent used crack (2018 DT 7.2).

e estimate of past year cocaine use in 2018 differed from