WORST CASE

HOUSING NEEDS

2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Ofce of Policy Development and Research

Visit PD&R’s website

huduser.gov

to nd this report and others sponsored by HUD’s Ofce of Policy Development and Research (PD&R).

Other services of HUD User, PD&R’s research information service, include listservs, special interest

reports, bimonthly publications (best practices, signicant studies from other sources), access to public

use databases, and a hotline (800-245-2691) for help accessing the information you need.

WORST CASE

HOUSING NEEDS

2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Prepared for

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

Ofce of Policy Development and Research

Prepared by

Thyria Alvarez

Barry L. Steffen

July 2021

WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Acknowledgments

The authors of this report gratefully acknowledge David A. Vandenbroucke

for his invaluable contributions to the Worst Case Housing Needs Report to

Congress over the years. David Vandenbroucke was a senior economist for the

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development who served for 28 years

before retiring in 2020. Mr. Vandenbroucke managed the American Housing

Survey and led its two survey redesigns in 1997 and 2015.

The authors would also like to thank Jennifer Turnham for her leadership and

expert advice in this report.

WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Foreword

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Department (HUD) is pleased to

present to the U.S. Congress its 18th biennial report on Worst Case Housing

Needs. The 2021 report on Worst Case Housing Needs provides national data

and analyzes the critical problems facing low-income renting families. The report

primarily draws on data from the American Housing Survey (AHS) sponsored

by HUD and conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. AHS is a comprehensive

national longitudinal housing survey conducted since 1973.

Households with worst case housing needs are very low-income renters—

households with incomes at or below 50 percent of area median income—who

do not receive government housing assistance and who pay more than one-

half of their income toward rent, live in severely inadequate conditions, or both.

The report finds that in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, 7.77 million

households had worst case housing needs. This is an improvement from the

record high of 8.5 million in 2011 but is substantially higher than the 5 million

households with worst case housing needs in 2001. There was no significant

change in the number of households with worst case housing needs between

2017 and 2019 despite favorable economic conditions.

While the overall number of worst case needs was unchanged, there were some

changes in the underlying drivers of worst case needs that push the count in

different directions. Two changes that lessened worst case housing needs were

modest income growth among households at the top of the very low-income

range (those with incomes between 30 and 50 percent of area median income)

and a modest increase in the availability of quality, affordable housing stock

for very low-income renters. Countering these positive developments were an

increase in total very low-income renters due to household formation and a

modest decrease in the number of very low-income renters receiving housing

assistance.

The 7.77 million households with worst case housing needs in 2019 included

2.27 million households with children, 2.24 million households headed by an

older adult (62 years or older), and 2.54 million single adults. About 13 percent

of households with worst case needs included people younger than 62 who

have disabilities, and about one-half were non-White or of Hispanic ethnicity.

Among very low-income renters, more than one-half of Asian, Native Hawaiian,

and Other Pacific Islander households had worst case needs, as did more

than 45 percent of Hispanic households, 44 percent of non-Hispanic White

households, and 36 percent of non-Hispanic Black households.

The key to ending worst case housing needs is increasing affordable housing.

In 2019, only 62 affordable units were available for every 100 very low-income

renter households. Only 40 affordable units were available for every 100

extremely low-income renter households. HUD is committed to ending worst

case housing needs and homelessness in America by increasing affordable

housing access. Key policy levers include increasing incomes of very low-

FOREWORD

WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

income renters, substantially expanding rental assistance, preserving the

existing assisted and affordable housing stock, and reducing barriers to the

production of new affordable housing.

This report captures housing need in the period immediately before the onset

of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic recession early in 2020.

The financial shock to the labor market and household incomes may cause

substantial increases in worst case needs when next measured with the 2021

American Housing Survey. The potential increase in worst case needs could

be dampened by strong fiscal relief packages that provide rental assistance to

sustain affordable housing and prevent homelessness during the pandemic.

Increased federal resources provided by pandemic stimulus packages,

fiscal year 2021 appropriations, and 2022 budget proposals are estimated

to generate affordable and assisted housing opportunities for approximately

330,000 households who would otherwise be at risk of worst case housing

needs. Further, targeted tax credits and resources proposed in the Biden

administration’s initial infrastructure plan would build and modernize more than

two million affordable and sustainable places to live. A Special Addendum in this

report discusses the recession, key features of the relief legislation, expected

impacts of the recession on housing outcomes, and potential implications for

future worst case needs estimates. The focus on the pandemic and response,

however, should in no way distract from the persistent, underlying structural gap

in the affordable housing market that is consistently documented in Worst Case

Needs reports. Ideally, a policy response that begins to bridge this affordable

housing gap will also seek to address geographic disparities in resource

allocation that contribute to inequities and pockets of distress.

Todd Richardson

General Deputy Assistant Secretary for Policy Development and Research

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

FOREWORD

vWORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Contents

Executive Summary ............................................................................................ vii

Few Significant Changes in Worst Case Needs Since 2017

....................... vii

Worst Case Needs Improved Slightly for Some Demographic Groups

and Household Types

.....................................................................................viii

Persistent Shortage of Affordable and Available Rental Housing

Is Especially Severe for Extremely Low-Income Households

....................ix

Conclusion

........................................................................................................xi

Section 1. Extent and Nature of Worst Case Needs

........................................ 1

Extent of Worst Case Needs in 2019

.............................................................. 1

Which Households Can Have Worst Case Needs?

........................................ 2

Severe Problems Trigger Worst Case Needs

................................................. 2

Inadequate Housing and Inadequate Income

............................................... 2

Progress in Reducing Homelessness

............................................................. 3

Prevalence of Worst Case Needs by Income

................................................ 4

Worst Case Needs Prevalence Among U.S. Households

.............................. 4

Demographics of Worst Case Needs

............................................................. 5

Worst Case Needs by Race and Ethnicity

...................................................... 5

Worst Case Needs by Household Type

.......................................................... 7

Disability and Accessibility in the American Housing Survey

....................... 10

Summary

.......................................................................................................... 11

Section 2. Shortage of Affordable Housing

..................................................... 13

Geography of Worst Case Needs

.................................................................. 13

Worst Case Needs and Housing Assistance by Region and

Metropolitan Location

.................................................................................... 14

Variation in Worst Case Needs Between Metropolitan Markets..................... 16

Factors Limiting Access to Affordable Rental Housing

............................. 18

How the Market Allocates Affordable Housing on a National Basis

.............. 18

Affordability, Availability, and Adequacy of the National Rental Stock

.......... 19

Measuring Whether Affordable Housing Stock Is Sufficient for Need

........... 20

CONTENTS

vi WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Rental Stock by Income ................................................................................. 21

Geography of Supply ...................................................................................... 22

Rental Stock by Region ................................................................................. 22

Rental Stock by Metropolitan Location .......................................................... 23

Summary ......................................................................................................... 24

Section 3. Understanding the Trend in Worst Case Needs ........................... 27

Drivers of Affordable Housing Demand .......................................................28

Other Factors Affecting Affordable Housing Supply and Demand ........... 29

Changes in Income Limits and Worst Case Needs ....................................... 31

Concluding Summary ..................................................................................... 32

Special Addendum. The Potential Effect of the COVID Pandemic

on Worst Case Needs ......................................................................................... 33

Economic Implications of the Pandemic ...................................................... 33

Federal Pandemic Relief Legislation .............................................................. 34

Eviction Moratoria ...........................................................................................35

What Percentage of Renter Households Are Behind on Rent

During the Pandemic? ....................................................................................35

How Well Will the AHS Measure Pandemic Effects in 2021? ..................... 37

Summary ......................................................................................................... 38

Appendix A. Detailed Data on Housing Problems and Supply

of Affordable Housing ........................................................................................ 39

Appendix B. Supplemental Exhibits ................................................................. 79

Appendix C. Federal Housing Assistance and Affordable

Housing Programs .............................................................................................. 81

Appendix D. Previous Reports to Congress on Worst Case Needs ............. 83

Appendix E. Data and Methodology ................................................................. 85

Using the American Housing Survey Data .................................................... 85

Household and Family Types ......................................................................... 86

Housing Assistance Status ............................................................................ 87

Housing Problems .......................................................................................... 87

Income Measurement .................................................................................... 88

Income Categories ......................................................................................... 88

Location ......................................................................................................... 89

Mismatch of Supply and Demand for Affordable Rental Housing ................. 89

Race and Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 90

Literature Cited ................................................................................................... 91

CONTENTS

viiWORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Worst case needs are a long-standing measure of the extent of unmet needs for

affordable rental housing of adequate quality. Renter households are defined

as having worst case needs for such housing if they have very low incomes—

household incomes at or below 50 percent of the area median income (AMI), do

not receive government housing assistance, and pay more than one-half of their

income for rent, live in severely inadequate conditions, or both.

Worst Case Housing Needs: 2021 Report to Congress examines the causes

of and trends in worst case needs using the most recent data from the 2019

American Housing Survey. The report finds that despite favorable economic

conditions in the 2017–2019 period, worst case housing needs persisted across

demographic groups, household types, and regions throughout the United

States. The unmet need for decent, safe, and affordable rental housing has

continued to outpace income growth and the ability of federal, state, and local

governments to supply housing assistance and facilitate affordable housing

production. As a result, the number of families with worst case housing needs

in 2019 remains modestly below historical high levels recorded since the Great

Recession of 2007–2009.

The report captures housing need in the period immediately before the onset

of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic recession early in 2020.

The financial shock to the labor market and household incomes can cause

substantial increases in worst case needs when next measured with the 2021

American Housing Survey. The major federal legislative response, however,

complicates the expectation and measurement of worst case needs. A Special

Addendum in this report discusses the recession, key features of the relief

legislation, expected impacts of the recession on housing outcomes, and

potential implications for future worst case needs estimates.

Few Signicant Changes in Worst Case

Needs Since 2017

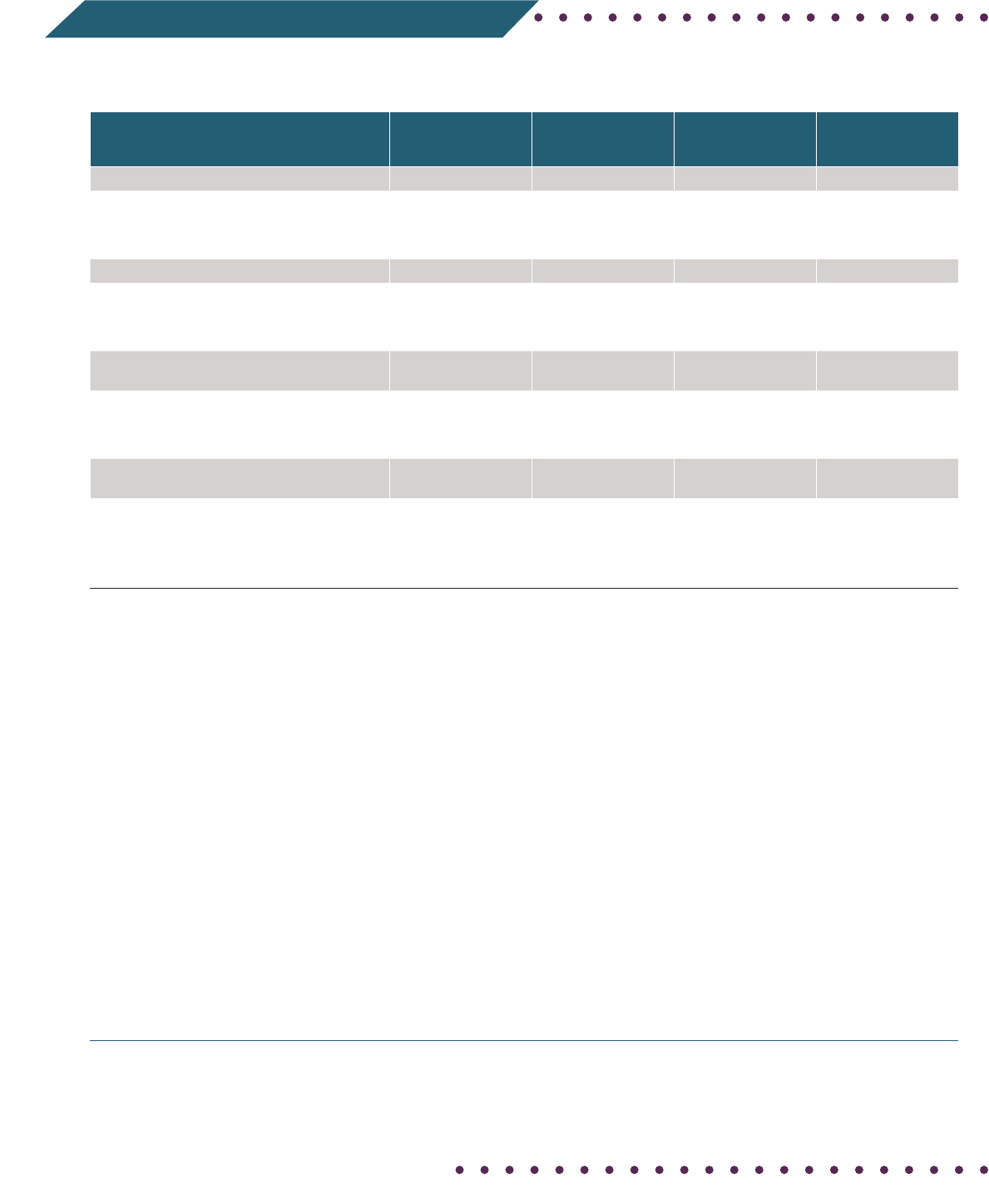

There were 7.77 million renter households with worst case needs in 2019, a

statistically insignificant increase of 50,000 cases compared with 7.72 million in

2017 (exhibit ES-1).

The latest figure continues to represent an improvement from the overall record

high of 8.5 million in 2011 but remains higher than during the years preceding

the 2007–2009 recession when there was greater availability of affordable

housing stock.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Executive

Summary

viii WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

0.0

6.0

8.0

9.0

5.0

7.0

4.0

2.0

3.0

1.0

2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

Renters with worst case needs (millions)

7.10

8.48

7.72

8.30

Exhibit ES-1. Change in Worst Case Housing Needs, 2009–2019

Source: HUD PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

7.72

7.77

10.0

The rate at which very low-income (VLI) renters experience

worst case needs also has improved only modestly in recent

years. The percentage of VLI renters experiencing worst

case needs (the “prevalence”) was 42.2 percent in 2019, a

slight reduction of 0.5 points from 42.7 percent in 2017. The

number of worst case needs increased more slowly (0.6

percent) than the number of VLI renters (1.8 percent). The

prevalence has improved moderately from the highest rate

observed since the 2007–2009 recession, 44 percent in

2011. The most recent biennial change is attributable to three

factors: (1) modest income growth among households at the

top of the VLI range (those with incomes between 30 and

50 percent of AMI); (2) a modest decrease in the number of

renters with very low incomes receiving housing assistance;

and (3) a modest increase in the availability of quality,

affordable housing stock for very low-income renters.

Although the relative shares of renters with incomes at

and below 30 percent of AMI (known as extremely low-

income, or ELI

1

) and with incomes between 30 and 50

percent of AMI did not change, the prevalence of worst case

needs increased among the lowest-income group while it

decreased among the next income group. As a result, ELI

renters account for the majority of worst case needs cases:

74 percent in 2019, a proportion that has not been seen since

2005.

1

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is required by law to set income limits or cutoffs that determine the eligibility of applicants for HUD’s

assisted housing programs. Extremely low-income (ELI) cutoffs for Section 8 programs historically meant household incomes at or below 30 percent of the

HUD-adjusted median family income for the metropolitan area. The FY 2014 Continuing Appropriations Act required ELI cutoffs to be set at the greater of 30

percent of HUD-adjusted median family income or the federal poverty guideline as published by the Department of Health and Human Services. The ELI cutoff

is capped by the VLI cutoff. See the Income Categories discussion in appendix E for further information.

Worst Case Needs

Improved Slightly for Some

Demographic Groups and

Household Types

The percentage of very low-income renters experiencing worst

case needs varied among demographic groups. In 2019, the

prevalence of worst case needs was 55 percent among Native

Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander households, 53 percent

among Asian households, 45 percent among Hispanic

households, 44 percent among non-Hispanic White

households, 36 percent among non-Hispanic Black households

and the other race and ethnicity group, and 23 percent among

American Indian or Alaska Native households. The prevalence

of VLI renters with severe problems narrowly decreased by

2 percentage points for non-Hispanic Whites and 1 point for

Hispanics but increased by 1.6 points for non-Hispanic

Blacks and by 2 points for other races or other ethnicities.

The percentage of VLI renters receiving rental assistance

decreased for all racial and ethnic groups between 2017

and 2019.

Three regions in the country—Midwest, Northeast, and

South—had an average decline of about 2 percent in the

share of renter households reporting worst case needs in 2019,

while the West saw an increase of almost 7 percent, offsetting

the decreases in other regions. The prevalence of worst case

needs decreased in suburbs and non-metro areas between

2017 and 2019 but not in central cities. The greatest decline

was observed in rural suburbs.

The prevalence of worst case needs slightly declined among

all household types, with the exception of households headed

by older adults. As the older adult population has increased

during the past 10 years, so, too, has the number of older adult

households with severe housing problems. The prevalence of

worst case needs decreased by 1 point among households

headed by someone younger than 62 while it increased by 1

percentage point among households headed by an older adult.

Despite minor changes, worst case needs remained a serious

and prevalent problem among all household types in 2019:

40 percent among families with children and among

households headed by older adults, 44 percent among

“other family” households (including multiple family members

without children), and 46 percent among “other nonfamily”

households (mostly single individuals). In absolute terms,

worst case needs involving other nonfamily households

increased during the last biennial period. In 2019, the worst

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

ixWORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

case needs tally included 2.5 million “other nonfamily”

households, compared with 2.3 million families with children,

2.2 million older adult households, and 0.7 million “other

family” households.

About one in eight renter households with worst case

needs—13 percent—included people younger than 62 who

have disabilities. Those 1 million households reflect limited

improvement since 2011, when national levels of worst case

needs peaked at 8.5 million households.

Persistent Shortage of

Affordable and Available

Rental Housing Is Especially

Severe for Extremely Low-

Income Households

For most households, worst case needs are caused by

severe rent burdens—that is, paying more than one-half

of income for rent. Inadequate market supply, competition

for affordable units, and a shortage of rental assistance

continued to pose a substantial challenge for VLI renter

households in 2019. Inadequate housing quality caused only

3 percent of worst case needs.

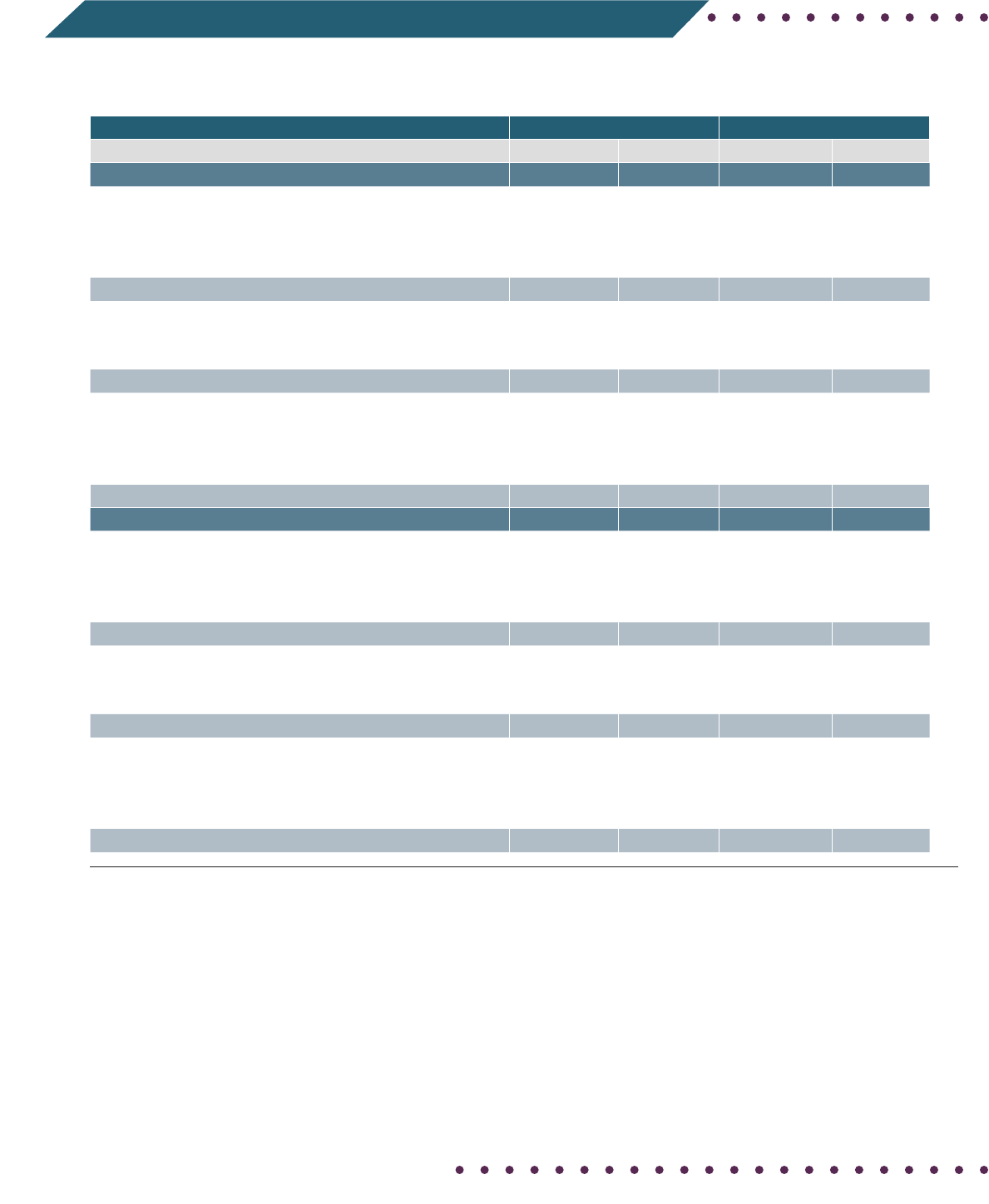

The net increase in worst case needs by 50,000 cases

between 2017 and 2019 is attributable to a combination

of the demographic changes affecting the number

of unassisted VLI renter households and the housing

market’s response to such quantitative drivers of affordable

housing demand. An attribution analysis estimated the

independent contribution of each of four increasingly focused

demographic factors to assess its effect on the number of

unassisted VLI renters and thereby on the number of worst

case needs. The positive or negative effects attributed to

the four demographic factors are represented by the first

four bars of exhibit ES-2: household formation increased

worst case needs because there was a net increase in

new households from population changes; tenure shift

reduced worst case needs because the growth in renters

lagged growth in homeowners; renter household income

shifts increased worst case needs because there was a net

increase of those with income below 50 percent of AMI; and

the housing assistance gap increased worst case needs

because there was a net increase in VLI renters lacking

rent subsidies from the federal, state, or local government.

(The columns of ES-2 are cascading in the sense that each

column begins where the previous one ends; the gray box

shows the net change in worst case needs.)

Source: HUD PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

159,000

increase from

population

growth

45,000

decrease from

homeowner

increases

relative to

renter share

20,000 increase

from renter

income changes

adding to VLI

numbers

218,000 decrease

from more

affordable and

available units for

VLI renters

Household

formation

Renter share Renter income

changes

Rental

assistance

gap

Affordable unit

competition

135,000 increase

from reduction in VLI

renters receiving

assistance

Net change:

50,000

increase

Exhibit ES-2. Contributions to Worst Case Needs

from Household Formation and the Rental

Assistance Gap were Offset by Less Competition

for Affordable Units from 2017 to 2019

Contributing most to the increase in worst case needs

were household formation, primarily among households

with extremely low incomes, and the widening of the

already unsettling gap in housing assistance relative to

households eligible to receive it. Although rising incomes in

a strengthening economy lifted some renter households with

incomes between 30 and 50 percent of AMI out of the VLI

population, there were larger increases in the number of ELI

renters. The only demographic factor that helped improve

the worst case needs picture between 2017 and 2019 was

the modest increase in homeownership rates. The primary

force helping to reduce housing problems in 2019 could be

considered economic rather than demographic: improvement

in the availability of affordable units in the housing market

associated with slightly less severe competition.

The four demographic factors together created the potential

for a substantial net increase in worst case needs between

2017 and 2019 by increasing the unassisted VLI renter

population. The market’s easing of competition among

renters for affordable units, however, successfully offset

much of the potential increase in worse case needs through

2019. The net increase attributed to demographic changes

was reduced an estimated 81 percent by modest expansion

in rental supply and associated changes in the availability

of affordable VLI units, as indicated by the fifth bar of

the exhibit. If the supply of affordable rental units fails to

increase at the same rate as the renter population, greater

demand would be expected to increase competition for

affordable units, drive up rents, and increase the prevalence

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

x WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

of worst case needs. Competition may include higher-

income households choosing to occupy units that would be

affordable to households with significantly lower incomes,

making those units unavailable to those with greater needs.

By the end of 2019, an increase of 771,000 rental units

affordable and available to VLI renters exceeded the increase

of 321,000 VLI renter households. For ELI renters, however,

the increase of affordable and available units by 137,000 fell

short of the increase of 200,000 renter households in this

group. Additions to the total supply of rental units, including

converted owner-occupied units, were limited to a 1-percent

increase between 2017 and 2019.

With modestly improved supply, rents did not increase as

much as renter incomes between 2017 and 2019. Median

housing costs

2

increased by 8.1 percent, building on a similar

increase in the prior period incomes (see exhibit 3-2). The

mean change in renter income during 2017 to 2019 was 13

percent, greater than the median change of 10.8 percent

(thus showing that the distribution of gains was skewed).

This mean value was influenced by a 17 percent increase

in income for the subgroup of households with incomes

exceeding 120 percent of AMI and, on the other hand, by an

increase of about 4 percent for ELI renters—which was less

than one-half that of any other income group (see appendix

A-14).

Similarly, compared with an increase in median housing

costs of 8.1 percent, mean housing costs increased by 9.1

percent among all renter households. For the ELI renter

subgroup, however, housing costs increased by 12 percent

during the 2-year period. As a result, the housing costs of

ELI renters increased almost three times faster than their

incomes from 2017 to 2019. This growing financial challenge

explains why the prevalence of severe problems among ELI

renters increased from 48.1 percent in 2017 to 49.2 percent

in 2019.

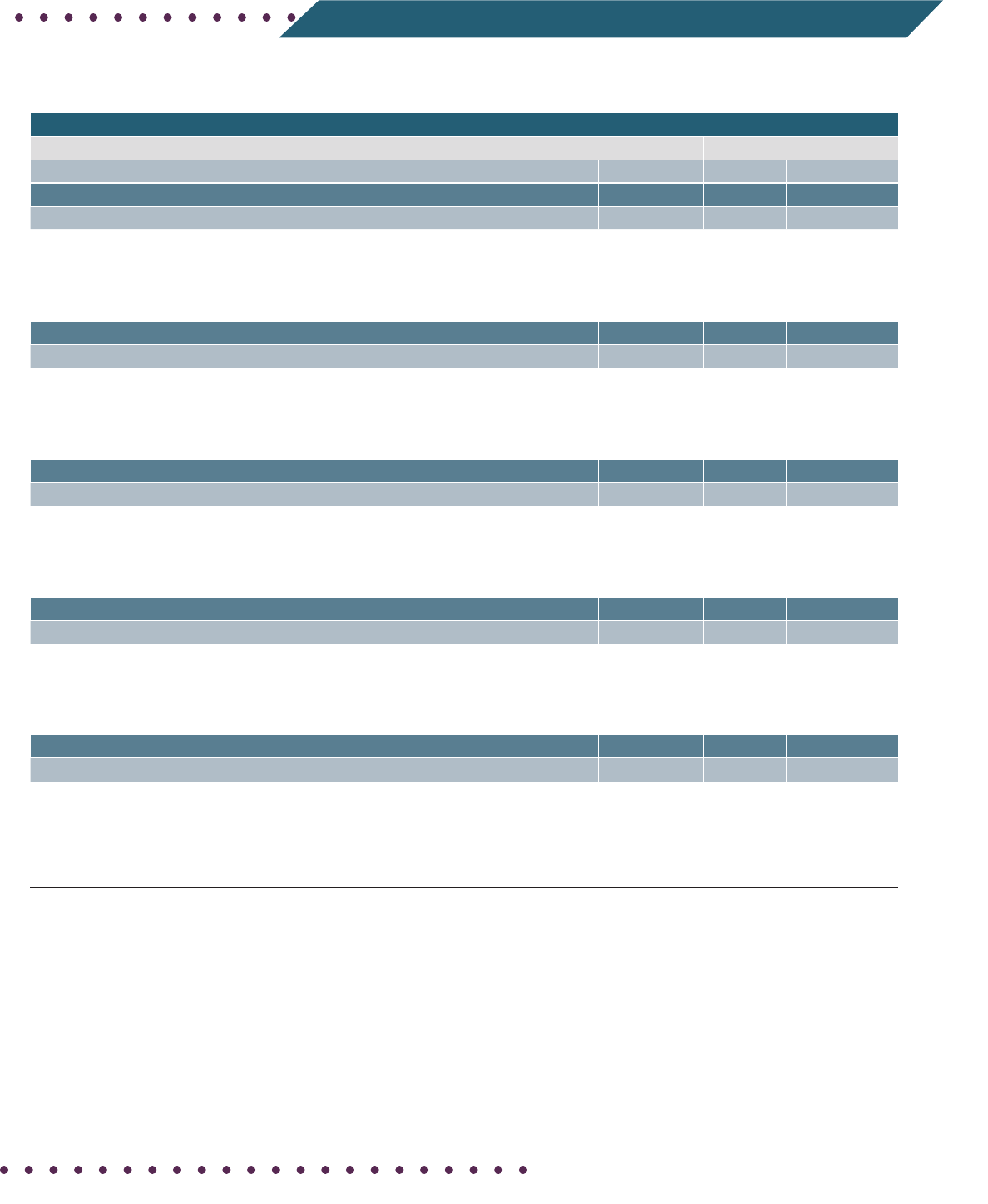

Access of VLI renter households to a sufficient supply of

naturally affordable rental units or assisted units is critical

to the extent of the worst case needs problem. Exhibit ES-3

presents how the availability of rental units affordable to VLI

households has responded to demand trends over the past

10 years.

2

Those housing costs include rent, utilities, property insurance, land rent, and association fees but exclude any separate security deposit or parking fees.

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

10,000

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

100.0

2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

Worst Case Needs (thousands)

Units per 100 Renter Households

Exhibit ES-3. Trends in Housing Supply

Mismatch and Worst Case Needs, 2009–2019

Affordable and available

units for ELI renters

(per 100 households)

Affordable and available

units for VLI renters

(per 100 households)

Worst Case

Needs

(thousands)

ELI = extremely low income. VLI = very low income.

Source: HUD PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

Although the supply of rental units slightly expanded in

2019, rental housing production has significantly lagged

behind household formation since 2010. At the same time,

the number of households with rental assistance has risen

only modestly and has not kept pace with the increase in

the number of VLI households. Rental units that have been

added tended to be in higher-rent properties. As a result,

the ratio of affordable and available units to VLI renters

followed a downward path from 2009 to 2017. After 2017,

there was some improvement, with the ratio increasing from

59 units per 100 renter households in 2017 to 62 units per

100 renter households in 2019. For ELI households, the ratio

of affordable and available units did not change—there were

only 40 affordable and available units for every 100 ELI renter

households in both 2017 and 2019. A more generous supply

of affordable and available housing for VLI households did

not generate proportional benefits for their ELI counterparts.

Increasing affordable housing supply by providing rental

and sustainable homeownership options for households

across the income spectrum—including by expanding rental

assistance, particularly for poorer households—therefore, will

be important for reducing worst case needs during the next

decade.

Availability ratios are as important as worst case needs

measurement for understanding affordable housing

problems. Availability ratios demonstrate the critical role of

rental assistance in expanding affordable housing options

for VLI renters: among VLI renters with access to affordable

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

xiWORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

housing, a large share have such access by virtue of the

rental assistance they receive. Availability ratios, when

compared with affordability ratios, also make clear the

striking competition for the most affordable housing. For each

affordability bracket, renters with incomes above the bracket

levels occupy large shares of units affordable to households

within the bracket. Such crowding-out affects 43 percent

of the units affordable to ELI renters, 40 percent of units

affordable at incomes of 30 to 50 percent of AMI, and 37

percent of units affordable at incomes of 50 to 80 percent of

AMI. As higher-income renters defer home purchases, they

continue to compete for affordable units and sustain rental

demand, limiting the availability of affordable rental units

for lower-income renters by two fifths. In short, the effect

of weak growth in the rental housing supply, a shortage of

rental assistance, and strong competition for available rental

units from higher-income renters seems to be having the

most detrimental effect on the availability of units affordable

to renters with incomes at and below 30 percent of AMI.

Improving the availability of affordable rental units for ELI

renters will be crucial to achieving substantial decreases in

worst case needs.

Conclusion

Worst case housing needs worsened slightly, but statistically

insignificantly, between 2017 and 2019 due to household

formation (new households formed as a result of population

increase) and widening of the rental assistance gap for

eligible very low-income households. Reductions in worst

case needs generally result when economic growth improves

household incomes and when the production of affordable

housing is sufficient to reduce market rents or, alternatively,

when rental assistance rates increase.

The leveling between 2017 and 2019 of housing problems

among the nation’s VLI renter households is primarily

attributable to a more adequate response of the housing

market to quantitative changes in demand for VLI-affordable

rental units. The progressive response of the housing

market blunted the potential increase in worst case needs

cases resulting from demographic and economic factors—

especially household formation, income loss, and the

widening gap between renter households eligible to receive

housing assistance and those receiving it. Households

reporting assistance decreased slightly even as the number

of VLI renter households expanded. An improved housing

market response that included modest housing production

helped increase the availability of affordable units for VLI

renters, although ongoing demand for more-affordable units

from higher-income renters continues to constrain availability

and prevent major reductions in worst case needs cases.

Three of five ELI renter households and three of eight VLI

renter households continued to lack access to affordable

and available housing units as of 2019. Rental housing

assistance—such as that offered by HUD programs,

other federal programs, states, or localities—helps many

vulnerable renter households who have such limited incomes.

Among VLI renters in 2019, 27 percent of households

were able to avoid worst case needs because they had

rental assistance. But rental assistance is in short supply:

because of inadequate funding, only about one in four

eligible households receives rental assistance. Another 30

percent were able to avoid severe housing problems in the

unassisted private rental market. The remaining 42 percent,

however, were left with worst case needs for assisted or other

affordable housing, and almost three-fourths of those were

ELI households.

As the economy grew during 2017 to 2019, the production

and supply of affordable homes remained insufficient to

satisfy the demand for affordable and available units by very

low-income renters. A broad strategy at the federal, state,

and local levels has long been needed to continue to grow

the economy, support market production and access to

affordable homes, and provide rental assistance to the most

vulnerable households. Additionally, beginning in early 2020,

economic stresses associated with the COVID-19 pandemic

created new critical needs to prevent eviction.

Several Congressional pandemic responses, as discussed in

the Special Addendum, provided increased federal housing

resources during 2020 and 2021. Stimulus funding provided

$46 billion to states for Emergency Rental Assistance to

assist tenants and landlords with pandemic-related rent

arrears. HUD’s FY 2021 appropriation increased subsidies

for public and assisted housing operations by $3.2 billion

from FY 2020 levels to address lost tenant rent contributions.

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provided $5 billion

that funded 70,000 new Emergency Housing Vouchers. The

Federal Housing Finance Agency announced a $711 million

allocation for the Housing Trust Fund in 2021, representing

twice the state funding for housing production as available

in 2020. The Treasury Department’s $10 billion Homeowner

Assistance Fund will help prevent foreclosures that ultimately

could increase the number of renter households with

worst case needs. The President’s FY 2022 Budget further

proposes to fund an additional 200,000 Housing Choice

Vouchers and increase housing production with $500 million

of increased funding for the HOME Investment Partnerships

program and $180 million to support 2,000 units of new

permanently affordable housing for older adults and people

with disabilities. Such housing supply-side and demand-

side resources are complemented by HUD’s work to reduce

regulatory barriers to affordable housing production and

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

xii WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

provide technical assistance to local governments to assist in

removing barriers that drive up housing costs.

With the expected impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and

associated economic difficulties in 2020 and 2021, worst

case housing needs have potential to increase substantially

before HUD’s next report. A comprehensive approach to

housing policy is sorely needed to address the long-standing

and evolving challenge of worst case housing needs.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Extent and Nature of

Worst Case Needs

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is the largest

federal provider of affordable rental housing. In response to a request by

Congress in 1991, HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research (PD&R)

periodically reports on the severity of worst case needs for affordable rental

housing, as collected in the biennial American Housing Survey (AHS). This

report is the 18th in the series of core reports.

3

Extent of Worst Case Needs in 2019

HUD analysts examined the 2019 AHS data to understand the evolving

dimensions of a persistently expanding shortage of decent and affordable rental

housing for lower-income households. The basic facts presented and examined

in the following pages are—

- In 2019, 7.77 million renter households had worst case needs (see

exhibit 1-1). These are renters that have very low incomes,

4

lack housing

assistance, and have either severe rent burdens or severely inadequate

housing (or both).

3

PD&R supplements the core reports on worst case needs with periodic topical reports. For a list

of previous titles, see appendix D.

4

Very low income and extremely low income refer throughout this report to the income levels of

renters. Very low incomes (VLI) are those incomes of no more than 50 percent of the area median

income (AMI), and extremely low incomes (ELI) are those incomes of no more than 30 percent

of AMI—typically below the poverty line. HUD programs use AMI based on local family incomes

with adjustments for household size, more precisely known as HUD-adjusted area median family

income, or HAMFI (see appendix E). Nationwide, median very low-income and extremely low-

income levels were $32,250 and $21,330 per year, respectively, in 2019 (see exhibit 3-2). These

income levels are for a family of four. ELI and VLI families may have incomes much less than

these national thresholds if they have fewer than four members or live in areas with lower median

family incomes.

SECTION 1. EXTENT AND NATURE OF WORST CASE NEEDS

Section 1

2 WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

0.0

6.0

8.0

9.0

5.0

7.0

4.0

2.0

3.0

1.0

2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

Renters with worst case needs (millions)

7.10

8.48

7.72

8.30

Exhibit 1-1. Growth in Worst Case Housing Needs, 2009–2019

Source: HUD PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

7.72

7.77

10.0

- Between 2017 and 2019, the number of very low-income

renters with worst case needs increased by a statistically

insignificant 0.6 percent, following a 7.1-percent

decrease observed during the 2015-to-2017 period. The

50,000 additional cases of worst case needs reflect a

significant increase of 225,000 cases among renters

with extremely low incomes, offset by a decrease of

175,000 cases among renters with incomes between 30

and 50 percent of AMI.

- Consistent with long-term trends, the primary problem

for worst case needs renters in 2019 was severe rent

burden resulting from insufficient income relative to rent.

Among all renter households, much of the 10.8-percent

increase in median incomes between 2017 and 2019

was consumed by an 8.1-percent increase in median

housing costs for renters. Severely inadequate housing

accounted for only 2.5 percent of worst case needs.

- Positive economic forces prevented worst case needs

from growing between 2017 and 2019. Competition for

affordable units eased slightly, and households moved

toward homeownership, a welcome contrast with the

recession-related challenges of mortgage foreclosures,

unemployment, and shrinking renter incomes that

increased worst case needs by 2.57 million households,

or 43.5 percent, between 2007 and 2011.

- In 2019, there were 18.39 million VLI renter households,

a 1.8-percent increase from 2017 levels that partially

reversed the 6.1-percent decrease seen in the 2015-

to-2017 period. In 2019, 42.2 percent of VLI renter

households and 49.2 percent of ELI renter households

had worst case needs.

- Worst case needs remained unchanged as a proportion

of U.S. households from 2017 to 2019 at 6.3 percent.

WHICH HOUSEHOLDS CAN HAVE WORST CASE

NEEDS?

By denition, households that can have worst case

needs are households that—

• Are renters.

• Have very low incomes—that is, incomes of no

more than 50 percent of the area median income

(as adjusted for family size).

• Do not receive housing assistance.

SEVERE PROBLEMS TRIGGER WORST CASE

NEEDS

Two types of severe problems determine whether

households have worst case needs:

1. Severe rent burden, which means that a renter

household is paying more than one-half of its

income for gross rent (rent and utilities).

2. Severely inadequate housing, which refers

to units having one or more serious physical

problems related to heating, plumbing, and

electrical systems or maintenance (problems

are listed in appendix E).

- Housing assistance prevents millions of renters from

experiencing worst case needs. The shortfall of housing

assistance relative to need increased between 2017 and

2019 as the number of assisted renters decreased by 2.7

percent. The share of VLI renter households receiving

housing assistance decreased by 1.3 points to 27.5

percent during the period.

- An important dimension of the affordable housing supply

gap is that affordable units are not necessarily available

to the renters who need them most; higher-income

renters occupy substantial shares of units that would be

affordable to the lowest-income renters.

With these key facts in mind, section 1 explores the current

extent and the demographic characteristics of worst case

needs—which households have such needs and what their

situations are.

Inadequate Housing and

Inadequate Income

Of the two types of severe problems that make up worst

case needs, severe rent burden is, by far, the more frequent

problem. As exhibit 1-2 illustrates, 97.5 percent of all

worst case needs renters, or 7.57 million households, had

severe rent burdens in 2019. Paying one-half (or more) of

a limited total income for rent leaves very little income for

SECTION 1. EXTENT AND NATURE OF WORST CASE NEEDS

3WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

other essentials, such as food, medical care, transportation

expenses, education, and child care.

Source: HUD PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

Exhibit 1-2. Severe Rent Burdens Drove

Worst Case Needs in 2019

Severe rent

burden only

Both severe

problems

Severely

inadequate

housing only

95.2%

2.3%

2.5%

N = 7.766 million renters with worst case needs.

Severely inadequate housing alone made up only 2.5

percent of worst case needs in 2019; 4.8 percent of renter

households with worst case needs, 374,000, had severely

inadequate housing, either alone or in combination with

severe rent burdens. Although severe housing inadequacies

represent only a small fraction of severe housing problems,

the number and share of worst case needs households

experiencing such quality problems remained almost

unchanged, with a 0.3-point decrease in the 2017-to-2019

period.

That severely inadequate housing causes such a small

fraction of worst case needs is the result of a decades-long

trend of improvements to the nation’s housing stock. More

stringent building codes prevent the construction of units

without complete plumbing or heating systems, and obsolete

units are demolished each year.

5

In addition, a portion of

severe physical inadequacies reported in the AHS likely

results from or reflects maintenance or upgrade activity

occurring in occupied units. Among all renter households,

3.0 percent of those with very low incomes and 1.0 percent of

those with higher incomes

6

had severely inadequate housing

in 2019. Nevertheless, the housing stock is continually

aging, and thousands of renters continue to live in severely

inadequate units. The costs associated with repairing severe

5

Changes in the overall housing stock are primarily driven by new construction and losses due to demolition and natural disasters (Econometrica, 2016).

6

Homeowners reported severely inadequate housing at even lower rates than renters: 1.9 percent of VLI homeowners and 0.5 percent of homeowners with

higher incomes had severely inadequate housing. See exhibit A-1B.

7

Divringi et al. (2019) estimated repair costs associated with quality deficiencies identified in the 2017 AHS and found that units occupied by renters with incomes

at or below the poverty line accounted for $25.5 billion, or 56.7 percent, of the aggregate estimated repair costs associated with rental units in the United States.

Older single-family and multifamily units occupied by poor renters had higher median repair cost estimates—$2,096 and $1,355, respectively—than newer units.

Similarly, Wallace et al. (2019) found that repair costs increase with the degree of housing inadequacy as measured by the AHS, with median costs for repairing

moderately and severely inadequate units estimated at $2,440 and $3,346, respectively.

quality deficiencies present another formidable barrier to the

ability of lower-income households to improve their housing

conditions. Landlords offering lower-priced units for rent

may similarly delay or avoid high maintenance and repair

expenses as units age.

7

PROGRESS IN REDUCING HOMELESSNESS

Individuals and families experiencing homelessness

clearly have the greatest need for affordable

or assisted housing. People experiencing

homelessness, however, are not included in ofcial

estimates of worst case needs because the AHS

covers only housing units and the households

that live in them, and people experiencing

homelessness, by denition, do not live in a housing

unit and are not surveyed by the American Housing

Survey (AHS).

a

In the 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report

to Congress, HUD estimated that 568,000 sheltered

and unsheltered homeless people were in the

United States during a given night in January 2019.

Most of these, 63 percent, were staying in residential

programs for people experiencing homelessness,

and the remaining 37 percent were staying in

unsheltered locations (HUD-CPD, 2019).

Since 2007, total homelessness on a given night

has declined by 15 percent, and homelessness

among families with children continues to decline.

This long-term progress, however, is threatened

by recent local trends among unsheltered and

chronically homeless populations in certain areas

of the country. Total homelessness has increased

modestly since 2016. The increase has been driven

by a growing unsheltered population in high-cost

markets, particularly in California, even as total

homelessness has continued to decline outside of

those areas. Although the number of people staying

in emergency shelters and transitional housing

programs continues to decline as the inventory of

beds in rapid rehousing programs increases, the

number of people staying in unsheltered locations

grew by 20 percent between 2016 and 2019.

Between 2016 and 2019, families with children

experiencing homelessness decreased by 12

percent, but the number of individuals experiencing

SECTION 1. EXTENT AND NATURE OF WORST CASE NEEDS

4 WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

homelessness increased by 11 percent. Chronic

homelessness among individuals grew by 24

percent even as the count of veterans experiencing

homelessness decreased by 6 percent during the

same period.

a

The AHS samples both occupied and vacant residential housing

units but excludes places such as group quarters or motels where

homeless persons may be sheltered (Census-HUD, 2017: 3–5).

Prevalence of Worst Case

Needs by Income

Because most cases of worst case needs are triggered by

severe rent burdens, the adequacy of household incomes

relative to rents of available units is crucial. Among the 18.39

million VLI renter households in 2019, 42.2 percent had worst

case needs (exhibit 1-3). The VLI category includes ELI renters,

who had an even greater prevalence of worst case needs

at 49.2 percent. ELI renter households constituted a large

share (63.9 percent) of VLI renter households in 2019, yet

their 1.7 percent increase between 2017 and 2019 was about

the same as the 1.9 percent increase of the 30–50 percent

of AMI population. ELI renter households experienced worst

case needs at a greater frequency in 2019, 49.2 percent, than

they did in 2017, 48.1 percent. As a result of their increased

prevalence of severe problems, ELI renter households account

for 74.4 percent of worst case needs in 2019, up from 72.0

percent in 2017, reflecting the difficulty of finding decent,

affordable housing at ELI levels.

8

Exhibit 1-3. Extremely Low-Income Renters Were Most

Vulnerable to Worst Case Needs in 2019

0–30% AMI

>30–50%

AMI Total VLI

Number of renters

(thousands)

11,748 6,640 18,388

Number that are worst

case needs renters

(thousands)

5,780 1,986 7,76 6

Percentage that are worst

case needs renters

49.2 29.9 42.2

AMI = area median income (HUD adjusted). VLI = very low income.

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

8

Of the 6.0 million ELI renter households without worst case needs, 4.0 million (or 66.2 percent) received rental assistance subsidized by HUD or other federal,

state, or local programs. In other words, only 2.0 million of the 11.7 million ELI renter households nationally (or 17.2 percent) avoided severe housing problems in the

unassisted private market in 2019. See exhibit A-1A.

9

Previous Worst Case Needs reports have documented much more rapid growth during the preceding 10 years. During 1999 to 2009, the number of worst case needs

increased from 4.86 million to 7.10 million, an increase of 46 percent.

Worst Case Needs Prevalence Among

U.S. Households

The estimated number of worst case needs increased by a

statistically insignificant 50,000 cases (or 0.6 percent) from

2017 to 2019, halting the decline in worst case needs observed

during the previous biennial period from 2015 to 2017. Over

the 10-year span from 2009 to 2019, however, the number of

households with worst case needs had grown by 9.5 percent,

or 671,000 households (exhibit 1-4).

9

Worst case needs

minimally decreased as a proportion of U.S. households during

the most recent 2-year period, from 6.4 percent in 2017 to 6.3

percent in 2019, but remains higher than the prerecession level

of 5.3 percent in 2007.

Exhibit 1-4. Growth in Worst Case Needs

Among All U.S. Households

2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

All households

(millions) 111.86 115.08 116.03 118. 29 121.56 124.14

Renters

with worst

case needs

(millions) 7.10 8.48 7.72 8.30 7.72 7.7 7

Worst case

needs as

percentage of

all households 6.34 7.3 6 6.65 7.0 2 6.35 6.26

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

As reflected in the most recent year of exhibit 1-4, this report

captures housing need in the period immediately prior to the

onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic

recession early in 2020. The financial shock to the labor market

and household incomes has potential to cause substantial

increases in worst case needs when next measured with the

2021 American Housing Survey. The major federal legislative

response, however, complicates the expectation and

measurement of worst case needs. A Special Addendum in

this report discusses the recession, key features of the relief

legislation, impacts of the recession on housing outcomes, and

potential implications for future worst case needs estimates.

Because the problem of worst case needs is primarily one of

a scarcity of units with affordable rents relative to the number

of renters with very low incomes, the balance of section 1

examines the demographics of the renters who have those

problems. Section 2 explores the dimensions of the inadequate

supply of affordable rental units, and section 3 summarizes and

SECTION 1. EXTENT AND NATURE OF WORST CASE NEEDS

5WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

integrates supply and demand issues to shed light on the

root causes and shifting dimensions of this persistent national

problem.

Demographics of Worst Case

Needs

Worst case needs are an economic reality for many of the

nation’s VLI renter households. The severe housing problems

that trigger worst case needs are widespread for such

households, yet notable variations exist among subgroups of

the population.

Worst Case Needs by Race and

Ethnicity

Worst case needs were found across all types of

communities, racial groups, and ethnic lines. Both similarities

and differences emerged when examining the three largest

racial and ethnic groups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic

Black, and Hispanic. This section also examines detailed

subgroups within the “all other races and ethnicities” group

10

to the extent supported by the AHS sample size. (See

exhibit 1-7.)

During 2019, non-Hispanic White renters accounted for

the largest number of households with worst case needs

(3.6 million) by race and ethnicity. Non-Hispanic Whites

accounted for 46.7 percent of worst case needs, followed by

Hispanics, with 24.7 percent; non-Hispanic Blacks, with 20.4

percent; and renters of all other races and ethnicities, with

8.2 percent. Together, the three largest race and ethnicity

groups accounted for 91.8 percent of worst case needs in

2019, and households headed by people of color accounted

for more than one-half—53.3 percent—of worst case

needs.

11

As suggested by exhibit 1-5, very low-income renters do not

experience worst case needs at a uniform rate. During 2019,

worst case needs affected 43.7 percent of VLI renters among

both non-Hispanic Whites and the other race and ethnicity

group—slightly less than the 45.1 percent prevalence among

10

In this section, race and ethnicity of households is based on the race and ethnicity of the householder as reported in the AHS data. People of color or households

of color refers to households that are not non-Hispanic White. “Other” is used in several ways. In the finest analysis that is consistently feasible with the AHS

data, “all other races and ethnicities” is the fifth of five main categories, comprising households of color in subgroups not otherwise listed or in a combination

of subgroups. In the more detailed breakout of exhibit 1-7, “Other race or ethnicity” has the same meaning but refers to a smaller residual category of households

because the exhibit provides additional categories by breaking down the AHS data to the full extent feasible. Finally, some portions of the narrative use “other” in

its plain sense of “ones not specified in the present context,” for example when groups of color are being compared to another group of color.

11

Similarly, the three largest race and ethnicity groups accounted for 92.1 percent of all VLI renter households nationally, and households of color accounted for

54.9 percent of VLI renter households.

12

See exhibit A-9.

Hispanics. Prevalence was lower among non-Hispanic

Blacks, with 36.1 percent having worst case needs. The lower

prevalence of worst case needs among Black households

reflects greater likelihood that Black households receive

housing assistance. Among Non-Hispanic Black renters with

very low incomes, 40.2 percent report housing assistance,

compared with only 24.3 percent for Non-Hispanic Whites,

23.2 percent for Hispanics, and 27.0 percent for all other

races and ethnicities (see exhibits A-9 and A-1A). Among

other factors contributing to this disparity, the geographic

distribution of housing assistance plays a prominent role, as

discussed in Section 2.

Variation in rates of housing assistance among VLI renter

households contributed to variation in the prevalence of

worst case needs and the likelihood that households avoided

severe housing problems unassisted in the private market.

12

Non-Hispanic White and Hispanic VLI renter households

had the best odds of avoiding severe housing problems in

the private market in 2019—32.5 percent of non-Hispanic

White VLI renters and 33.1 percent of Hispanic VLI renters

avoided severe problems without housing assistance. Only

about one-fourth of non-Hispanic Black and other VLI renter

households—23.8 and 29.2 percent, respectively—avoided

severe problems in the private market without housing

assistance.

SECTION 1. EXTENT AND NATURE OF WORST CASE NEEDS

6 WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Exhibit 1-5. Very Low-Income Renters from All

Household Types and Racial and Ethnic Groups

Experienced Worst Case Needs in 2019

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

Subgroup VLIR with worst case needs (percent)

Subgroup share of all very low-income renters (percent)

30%

10%

40%

50%

20% 30% 40%

50%

0%

Other race/ethnicity

Hispanic

Non-Hispanic Black

Non-Hispanic White

VLIR = very low-income renters.

Source: HUD PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

The position of the markers in exhibit 1-5 reflects each

group’s share of VLI renter households and the rate at which

they experience worst case needs. Groups account for a

greater share of worst case needs as their markers move

toward the upper-right quadrant. As a share of VLI renter

households, the subgroups based on race and ethnicity span

a range of 37.2 percentage points, but the prevalence of

worst case needs varied by only 9.0 percentage points. The

all other races/ethnicities group and Hispanic households are

particularly more likely to have worst case needs than other

subgroups, relative to their share of the VLI renter population.

Other race and ethnicity groups, not included in the three

main race and ethnicity categories (non-Hispanic White, non-

Hispanic Black, and Hispanic), represent a small proportion

of VLI households (7.9 percent), thus appearing in the

upper-left quadrant of the exhibit. About 44 percent of these

households, however, experience worst case housing needs.

Non-Hispanic White households account for a relatively large

share of the VLI renter household population (45.1 percent)

and have a relatively large prevalence of worst case needs

(43.7 percent), thus appearing in the upper-right quadrant

of the exhibit. Except for non-Hispanic Black households, all

subgroups have a larger share of their VLI renter household

population afflicted with worst case needs than the national

average of 42 percent.

Exhibit 1-6. Growth in Worst Case Needs Among

All Racial and Ethnic Groups, 2009-2019

Source: HUD PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

Worst case needs (thousands)

Other Race/Ethnicity

Hispanic

Non-Hispanic Black

Non-Hispanic White

0

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

2,000

1,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

437

587

601

621

620 633

1,582

1,971

1,845

2,104

1,884 1,922

1,640

1,820

1,657

1,800

1,578 1,588

3,436

4,097

3,618

3,778

3,634 3,623

Exhibit 1-6 shows a slight increase in worst case needs

among households of color between 2017 and 2019 and

a small decrease among non-Hispanic Whites. Hispanic

households had the greatest increase of worst case

needs, 38,000 households, followed by an increase of

13,000 additional cases among renters of other races and

ethnicities, and about 10,000 cases more among non-

Hispanic Blacks. The proportion of VLI renters receiving

housing assistance decreased overall between 2017 and

2019. Renters in the all other races and ethnicities group

experienced the largest decrease in the housing assistance

rate, a reduction of 5.3 points from 32 percent in 2017 to 27

percent in 2019.

Despite those absolute changes in numbers, the prevalence

of worst case needs among VLI renters differed among racial

and ethnic groups. The rate of worst case needs modestly

improved for non-Hispanic Whites, decreasing 2 points from

46 percent in 2017 to 44 percent in 2019, and Hispanics,

decreasing 1 point from 46 to 45 percent. The prevalence

increased by 1.6 points among non-Hispanic Blacks, from

34.6 to 36.1 percent, and by 2 points among the all other

races and ethnicities group, from 42 to 44 percent.

Exhibit 1-6 also illustrates differences in the long-term growth

of worst case needs. Between 2009 and 2019, worst case

needs increased 9.5 percent overall but increased only 5.4

percent for the largest subgroup of VLI renter households:

non-Hispanic Whites. During the last 10 years, non-Hispanic

SECTION 1. EXTENT AND NATURE OF WORST CASE NEEDS

7WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

Blacks saw a decrease of 3.2 percent in the number of worst

case needs. Worst case needs expanded much more rapidly

during these 10 years among other people of color, with

increases of 21.5 percent among Hispanics and 44.9 percent

among renters of all other races and ethnicities. In the most

recent biennial period, the population of non-Hispanic White

VLI renter households grew by 4.5 percent. The change

among minorities varied among subgroups; while Hispanic

VLI renters households increased by 4.3 percent, economic

recovery reduced the VLI renter populations of non-Hispanic

Blacks and all other races/ethnicities by 3.7 and 2.8 percent,

respectively.

13

The series of reports produced by the Native American Housing Needs Study are available at https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-

research-022117.html.

Although renters of color who are not Hispanic or non-

Hispanic Black make up a small share (8.2 percent) of

households with worst case needs, the American Housing

Survey sample is large enough to provide detailed national

estimates for some subgroups within this category. Beginning

with the 2017 AHS, HUD has reported estimates of worst

case needs for Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, and

Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander households. This

detail provides additional insight into the composition of the

small but growing group of “other race or ethnicity” renters

(exhibit 1-7).

Exhibit 1-7. Worst Case Needs Among Detailed Race and Ethnicity Subgroups in 2019

Non-

Hispanic

White

Non-

Hispanic

Black

Hispanic Asian American

Indian or

Alaska

Native

Native

Hawaiian or

Other Pacic

Islander

Other

Race/

Ethnicity

0–30% AMI renter households

(thousands)

5,083 3,050 2,651 526 219 60 158

Worst case needs (thousands) 2,582 1,288 1,443 300 (D) (D) 71

Percent with worst case needs 50.8 42.2 54.4 57. 0 (D) (D) 44.9

>30%–50% AMI renter households

(thousands)

3,207 1,343 1,607 273 68 17 125

Worst case needs (thousands) 1,041 301 479 120 (D) (D) 32

Percent with worst case needs 32.5 22.4 29.8 44.0 (D) (D) 25.6

Total very low-income renter

households (thousands)

8,290 4,393 4,258 799 287 77 283

Worst case needs (thousands) 3,623 1,589 1,922 420 66 42 103

Percent with worst case needs 43.7 36.2 4 5.1 52.6 23.0 54.5 36.4

AMI = area median income. Other race / ethnicity = racial or ethnic group not listed individually or consisting of multiple races or ethnicities.

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

Exhibit 1-7 shows that Asian households account for more

than one-half of worst-case households within the all

other races and ethnicities group presented in exhibit 1-6,

representing 4.3 percent of all households with worst case

needs. The prevalence of worst case needs among Asian VLI

renter households, 52.6 percent, was higher than among any

other racial or ethnic group except the small Native Hawaiian-

Pacific Islander group.

Together, American Indian or Alaska Native and Native

Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander households accounted

for 2.7 percent of all cases of worst case needs in 2019.

Although those estimates provide one indication of the

prevalence of severe housing affordability and quality

problems among those populations, HUD’s Native American

Housing Needs Study also found that overcrowding and

doubling up were far more common among Native American

households compared with other households in the United

States.

13

Thus, estimates of worst case housing needs should

be viewed as one component of a larger body of evidence on

housing problems among American Indian or Alaska Native

and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander households in

tribal and urban areas.

Worst Case Needs by Household

Type

The composition of different households reflects variations

in their stage of life, income and resources, and housing

needs. Other nonfamily households (single adults, unmarried

couples, and roommates) constituted the largest share of

households experiencing worst case needs in 2019—32.6

SECTION 1. EXTENT AND NATURE OF WORST CASE NEEDS

8 WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

percent—followed by families with children, with 29.2

percent; older adult households without children (hereafter,

older adult households), with 28.9 percent; and other family

households, with 9.3 percent (exhibit 1-8).

14

Exhibit 1-8. Very Low-Income Renters from All

Household Types and Racial and Ethnic Groups

Experienced Worst Case Needs in 2019

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

Subgroup VLIR with worst case needs (percent)

Subgroup share of all very low-income renters (percent)

30%

10%

40%

50%

20% 30% 40%

50%

0%

Other family

Other nonfamily

Older adults Families with children

VLIR = very low-income renters.

Source: HUD PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

As a share of VLI renter households, the subgroups based

on household type span a range of 21.8 percentage

points, but the prevalence of worst case needs varied by

only 5.8 percentage points. Exhibit 1-8 shows that three

household types share very similar proportions of VLI renter

households—30.7 percent families with children, 30.3

percent older adult families, and 30.0 percent other nonfamily

households—while only 9.0 percent are other family

households. “Other” nonfamily households and “other” family

households are somewhat more likely to have worst case

needs than other subgroups. Compared with the average

prevalence of 42.2 percent, 43.7 percent of other family

households and 45.9 percent of other non-family households

have worst case needs.

The variations in prevalence among these subgroups,

although limited, may reflect the result of housing programs

prioritizing families with children, older adults, and veterans.

Families with Children. The largest VLI group by household

type, families with children, was the only household type that

saw a decrease in worst case needs cases between 2017

and 2019. The number of families with children having worst

case needs decreased by 300,000 during the 2017-to-2019

period, contributing to a total reduction of 965,000 cases

since their housing problems peaked in 2011.

14

See appendix E for more on the composition of household types. Families with children may include a parent with child and unmarried partner. Either family or

nonfamily households may include same-sex partners. The Household Demographics table for AHS 2019 in the AHS Table Creator is illustrative: https://www.

census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/data/interactive/ahstablecreator.html.

Worst case needs decreased, in part, because VLI renter

households with children decreased by 545,000 between

2017 and 2019. This decrease took place wholly among

households with incomes at and below 30 percent of AMI.

Along with rising incomes, the decline in the number of renter

families with children appears to have had a causal role.

Nationally, the number of renter households with children was

reduced by 6.5 percent between 2017 and 2019.

Although progress is being made—partly attributable

to income gains among these households—the number

of families with children experiencing worst case needs

remained above prerecession levels. The share of VLI renter

households with children experiencing worst case needs

moderately decreased by 1.3 percentage points from the

2017 level to 40.2 percent in 2019, and the percentage

reporting housing assistance also declined from 26.8 to 25.6

percent.

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey data

Worst case needs (thousands)

Other

nonfamily

Other

family

Families

with children

Older adults,

no children

0

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

2,000

1,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

2,401

2,969

2,676

2,758

2,497

2,535

633

801

741

805

716

720

2,734

3,236

2,833

2,888

2,571

2,271

1,328

1,470

1,471

1,853

1,932

2,241

Exhibit 1-9. Growth in Worst Case Needs

Among All Household Types, 2009–2019

Without housing assistance, substantially more cases of

worst case needs would occur. Among VLI renter households

with children, 1.45 million reported having rental assistance

in 2019 and, by definition, could not have worst case needs.

Only about one in four VLI renter households with children

received housing assistance, which helps account for the

SECTION 1. EXTENT AND NATURE OF WORST CASE NEEDS

9WORST CASE HOUSING NEEDS: 2021 REPORT TO CONGRESS

fact that the greatest share of worst case needs occurred in

such families.

15

Older Adult Households. The number of older adult

households experiencing severe housing problems has

steadily climbed over the past decade. During 2019, 2.24

million older adult

16

renters had worst case needs, an

increase of 607,000 since 2017, even as 73,000 more of

these households reported receiving rental assistance in

2019. The increase is largely attributable to the growing

population of older adult VLI renter households. The

proportion of older adult VLI renter households with worst

case needs was 40.3 percent in 2019, marginally greater

than the rate for families with children and representing a

1.3-point surge since 2017. Although nearly 4 in 10 older

adult VLI households received housing assistance in 2019—

a 2.9-point decrease since 2017—aging baby boomers are

likely to continue to be a key demographic facing housing

problems in the years to come.

17

Other Family Households. After considering families with

children and older adult households, other households can

be divided into those that include multiple members of a

given family and those that do not. Other family households

include those such as married couples who are childless,

one or more parents with adult children at home, adult

siblings sharing an apartment, and householders boarding

an older adult parent.

18

Other family households constitute the smallest category

in exhibit 1-9, contributing 720,000 worst case households

in 2019. The rate of worst case needs among VLI renter

households in this group was 43.7 percent, exceeding the

prevalence for either families with children or older adult

15

Estimates of the number of rental households that reported receiving rental housing assistance are presented for various subgroups in the exhibits of appendix

A. AHS estimates of assisted very low-income renters in this report rely on self-reported data, which primarily include HUD-assisted households and may also

include households assisted through other federal, state, or local programs, such as U.S. Department of Agriculture rental housing subsidies. As expected,

HUD administrative data matching procedures suggest that excluding households assisted by non-HUD programs reduces the number of households classified

as receiving housing assistance. For the purposes of this report, however, households receiving assistance from a non-HUD program are not classified as