abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................. 2

I. NEIGHBORHOOD CHANGE IN BALTIMORE: AN OVERVIEW ................................................................................... 5

A. Citywide trends ......................................................................................................................................................... 6

B. Neighborhood trajectories ...................................................................................................................................... 11

II. THE DIMENSIONS OF NEIGHBORHOOD CHANGE IN BALTIMORE ....................................................................... 16

A. Demographic change .............................................................................................................................................. 16

1. Black population change ..................................................................................................................................... 16

2. White and Latinx population change .................................................................................................................. 19

B. Housing market change ........................................................................................................................................... 20

1. Real estate market dynamics .............................................................................................................................. 22

2. Homeownership ................................................................................................................................................. 30

III. KEY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTERS ........................................................................................................................... 33

A. Predominantly black moderate-income neighborhoods ........................................................................................... 34

B. The Northeast Triangle ............................................................................................................................................ 36

C. Gentrifying neighborhoods ...................................................................................................................................... 40

IV. CLOSING COMMENTS .............................................................................................................................................. 46

APPENDIX I: METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................................................... 50

APPENDIX 2: CORRELATIONS BETWEEN ECONOMIC, DEMOGRAPHIC,

AND HOUSING-MARKET FACTORS ............................................................................................................................... 52

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods:

Changes in racial/ethnic composition and

income from 2000 to 2017

by Alan Mallach

Prepared for the Abell Foundation

Baltimore, Maryland

April 2020

The opinions in this report are those of the author and do not represent the position of either the Abell Foundation

or the Center for Community Progress.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 2

INTRODUCTION

Urban neighborhoods—their dynamics, their eects, and their transformation in the 21st century—have

become one of the most heatedly contested issues in the ongoing discussion about the present and future of

American cities. Few discussions about urban neighborhoods fail to bring in the issue of gentrication, which

has become one of the most widely used (and, I would suggest, misused) words in the urban lexicon. At the

same time, research has increasingly shown the power of neighborhood eects, and how devastating living

or growing up in a distressed, concentrated poverty area can be on people’s health and well-being, their life

expectancy, and their prospects for better earnings and upward mobility later in life.

All of these issues are powerfully present in Baltimore, a city that in many respects is experiencing strong

revival, and in others, continuing decline. Baltimore is a city intensely polarized by race and economic status.

What happens in Baltimore’s neighborhoods, whether they are gentrifying or declining, continuing to

struggle or growing in strength, not only is critical for framing public policy, but also denes what kind of a

city Baltimore is, and what kind of city its residents want it to be. And yet, little is known about what is actually

going on. In recent news posts, Baltimore has been portrayed by President Trump as a “rat and rodent infested

mess,”

1

and by a highly publicized national study as one of the ve most rapidly gentrifying cities in the United

States.

2

Neither is true, of course, although Baltimore undoubtedly has some neighborhoods that are in deep

distress, and some neighborhoods that are gentrifying.

The purpose of this report is to ll in part of that knowledge gap by providing an initial picture of what has

actually been happening in Baltimore’s neighborhoods since the beginning of the 21st century—that is,

to what extent have neighborhoods moved upward economically, moved downward, or stayed largely the

same, and what does that mean in terms of population change, economic condition, and housing markets.

Specically, this report looks at Baltimore’s roughly 200 census tracts, breaking them down into categories

by race and by economic level in 2000 (as described in the next section) and presenting how they’ve changed

since. For example, have neighborhoods that were similar economically but dierent racially in 2000 followed

similar or dierent trajectories from then until now? And if their trajectories were dierent, in what ways?

I look at how neighborhoods have changed; whether they moved upward or downward economically; whether

they gained or lost population; how their racial composition did or did not shift; and how their housing market

conditions, including home ownership rates and sales prices, changed. I tried to get a sense of how many and

which neighborhoods were gentrifying versus declining, and how those trends relate to population change,

particularly in the city’s black population.

Although I look closely at gentrication in Baltimore, this report is not about gentrication as such. It is

about the larger picture of neighborhood change. Gentrication is one part of that picture—a signicant part,

but one that aects only a small minority of Baltimore’s neighborhoods. Most of Baltimore’s neighborhoods

are changing, but in dierent ways. Those changes are being driven by major demographic shifts in the city’s

population, which are in turn driving major changes in Baltimore’s housing market. This local change

parallels the hollowing of the middle class and the increasing polarization of wealth and poverty seen at

the national level.

The largest single factor driving change in Baltimore is that Baltimore is losing its working- and middle-class

families. That factor plays out very dierently across the city’s racial divide. While Baltimore is losing white as

well as black middle- and working-class families, it is gaining a young, highly skilled and high-earning white—

but not black—population through in-migration. As a result, the white population is becoming more auent,

1 Tweet on July 27, 2019; the exact wording was “[Rep. Elijah] Cumming District is a disgusting, rat and rodent infested mess.”

2 National Community Reinvestment Coalition, Shifting Neighborhoods: Gentrication and Cultural Displacement in American Cities (March 2019);

e.g., “Baltimore and Philadelphia metro areas are in the top 10 list, with the fourth and fth largest number of gentried tracts in the study” (p.15).

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 3

and the black population is becoming poorer. That shift reverberates through the housing market. In those

areas to which young, auent white households are moving, housing demand is strong and prices are rising.

In those areas from which working- and middle-class black families are leaving, housing demand is weak,

prices are largely at, and abandonment is distressingly common.

All of those who are engaged in working to make Baltimore a healthier, stronger city need to ask the question:

Why is Baltimore losing its working- and middle-class families, particularly its African American ones? I hope

this report will encourage conversation around that question.

The relationship between demographic change and market change underlies most of what is happening to

Baltimore’s neighborhoods. Markets may not be fair, but they are powerful, and they tend to work in ways

little aected by political decisions and community aspirations. They can be inuenced, but only if they are

thoroughly understood. This is particularly relevant to the subject of gentrication. In light of the role that

this issue plays in many discussions of neighborhood change in Baltimore, I will address it briey in this

introduction, and then in more detail later.

While gentrication may have dierent meanings for dierent people, I dene it here, as do almost all

researchers who study and write about it, as a combination of signicant increases in both house prices and

household incomes in a given area.

3

This reects the understanding that gentrication is about both the inux

of more auent households into an area and the increase in that area’s house prices above some citywide

or regional benchmark. It is not the same as displacement. Displacement is a dicult term because as with

gentrication itself, it can mean dierent things to dierent people in dierent contexts. Most precisely,

displacement refers to an involuntary process—that is, people being forced to leave their homes, for any

number of reasons—as opposed to people voluntarily moving, again for any number of reasons.

The data cannot tell us whether displacement, in the sense given above, is happening in Baltimore’s relatively

small gentrifying area, but the data suggest, in the words of progressive journalist Jarrett Murphy, that “the

issue isn’t displacement of the poor, it’s replacement.”

4

The one available statistical measure of displacement,

the rate of evictions, shows no correlation with any indicator of gentrication. It is a product, above all, of

poverty and high rental cost burden. I am not arguing that there is no displacement, as dened above,

connected to gentrication in Baltimore. As philosophers and scientists have long pointed out, proving

the absence of something is often impossible. I nd, however, that the changes taking place in those

neighborhoods are fully explained by replacement, not displacement. In the course of that process, far more

lower-income white households have been replaced than black households, while in many cases out-moving

larger black households have been replaced by smaller black households.

This report is not a complete picture of Baltimore’s neighborhoods. Neighborhoods are complicated things.

A neighborhood is more than its economic trajectory; it is a product of the commitment of its residents and

property owners, or the absence of that commitment; the presence or absence of neighborhood organizations

and institutions; the levels and character of the interactions among its residents, and much more. At the

same time, understanding economic and demographic trends and how they then drive housing markets

is fundamental to understanding neighborhoods, while many market-related factors, such as trends in

homeownership rates or population movements, powerfully aect the social as well as the economic dynamics

of the neighborhood.

3 In some cases, researchers add signicant increase in educational attainment (particularly the percentage of adults with a bachelor’s or higher

degree) to the rst two factors. This is the basic framework that was adopted by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition in the study cited

earlier; I do not disagree with the framework, although I question how it was applied.

4 Jarrett Murphy, “The Complicated Research on how Gentrication Aects the Poor,” CityLimits, November 20, 2015. https://citylimits.

org/2015/11/20/the-complicated-research-on-how-gentrication-aects-the-poor/

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 4

Finally, this report is not about pointing ngers. The picture painted here is in large part the reection of

powerful and long-term changes in our nation’s demographic and economic character and reects historical

patterns of discrimination, segregation, redlining, and white ight. The ability of the city’s current community

leaders and advocates to rapidly undo the city’s underlying social, economic, and physical challenges is

severely limited. That said, there are many things that can be done to redress inequity, and the strategic

framework recently adopted by the city’s Department of Housing and Community Development represents a

serious, thoughtful eort to begin grappling with many of them.

5

I look rst at the larger city picture, and the patterns of variation in neighborhood change by race and

economic condition, followed by a discussion of the implications of change for population change, as well

as change in house values, home ownership rates, and other key neighborhood indicators. The next section

looks at particular patterns of neighborhood change, including gentrication and the decline of middle-

income neighborhoods. The following section looks at three neighborhood clusters of particular signicance in

Baltimore, and a nal section oers some key takeaways with particular implications for public policy.

Some of the ndings presented in this report may be surprising, and some may be upsetting. That said, it

is important to lay out the facts as dispassionately as possible, so that they can be understood, and so they

can help further the discussion among people who care about the city and its neighborhoods to bring about

change for the better to Baltimore’s neighborhoods. The thrust of this report, however, is not to recommend

what those changes should be, but to lay out, as best I can, the picture of neighborhood change in a dynamic,

beautiful, but deeply challenged city.

To study Baltimore’s neighborhoods, I used census tracts, the unit created and used by the U.S. Census Bureau

for small area analysis. With the city divided into nearly 200 tracts, they are small enough to be meaningful

and relatively homogenous, and they have the advantage that nearly all datasets are available by census tract.

Census tracts are not the same as the Neighborhood Statistical Areas (NSAs) used by the city, but the two are

often roughly comparable. Thus, when I refer to a neighborhood by name in this report, the reader should

understand that I am referring to areas that are similar but not identical to that named neighborhood.

I then segmented the city’s census tracts into categories based on race and economic condition. With respect

to race, I used the percentage of black population, and with respect to economic level, I used the median

6

tract household income. I looked at data for 2000, 2010, and 2017. The breakdown in race and income is

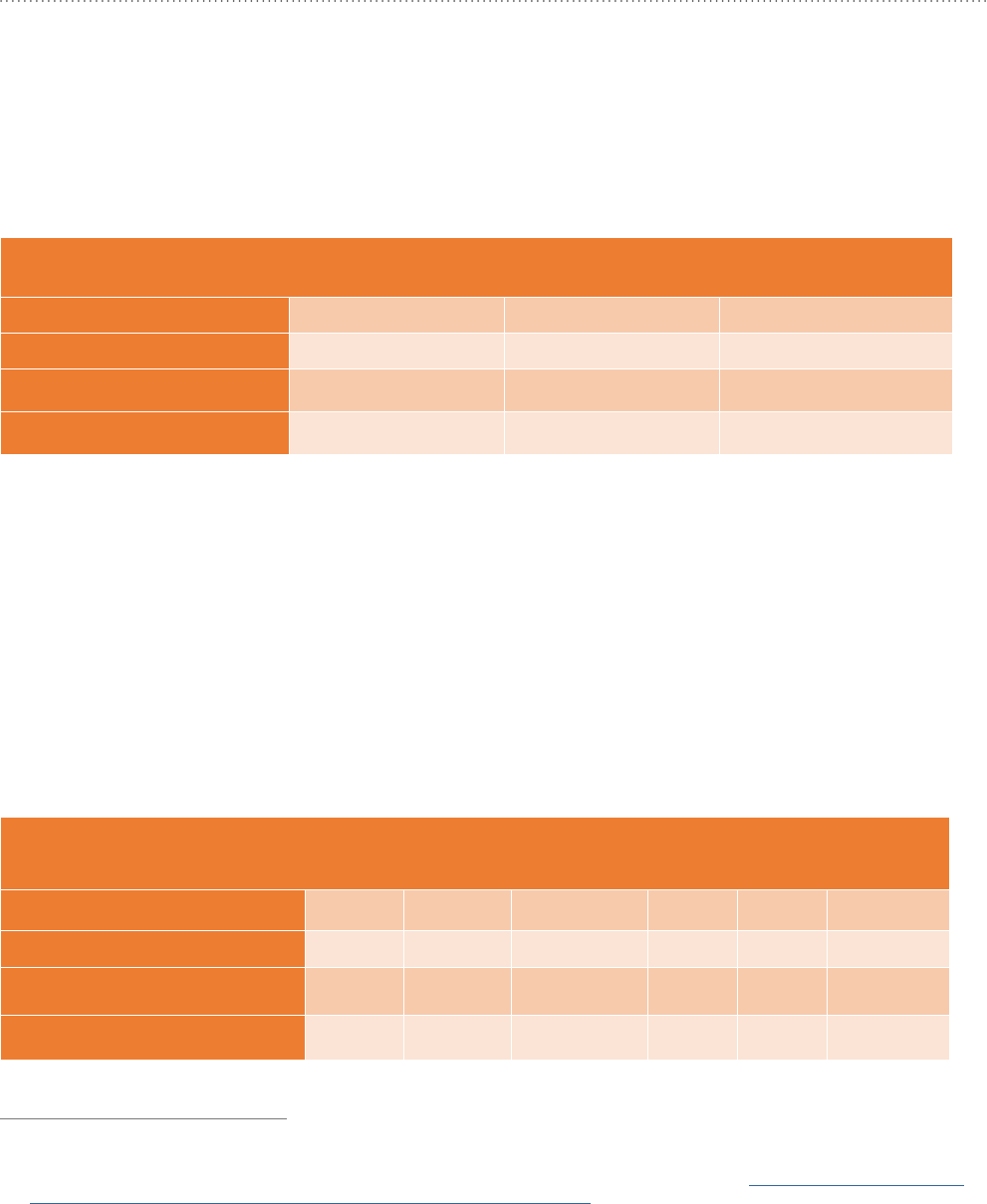

shown in the matrix in Table 1 (income ranges are relative to the citywide median household income). I use

the descriptive terms for the economic and racial composition of the city’s neighborhoods shown in the matrix

frequently in the report.

5 Baltimore City Department of Housing and Community Development, A New Era of Neighborhood Investment: A Framework for Community

Development, November 2018.

6 Median refers to the midpoint of a range of numbers (i.e., that number where half of the numbers are lower and half are higher). It is dierent

from average, which is the sum of the numbers divided by the number in the range.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 5

Table 1: Neighborhood Category Matrix By Economic Level and Racial Composition

ECONOMIC

COMPOSITION

RACIAL

COMPOSITION

Neighborhood Type Range

0-29.9% Black 30-69.9% Black 70-100% Black

Predominantly

White

Mixed

Predominantly

Black

Low Income 0-59.9% X

Moderate Income 60-99.9% X X X

Middle Income 100-149.9% X X X

Upper-Middle Income 150-199.9% X X X

Upper Income 200%+ X

The matrix oers a total of 15 possible neighborhood categories. The actual number of categories is 11, as

shown by “X” in the table. There are no census tracts (e.g., predominantly white low-income tracts) in the other

categories. The income ranges—those within which the tract median falls—for the three time periods I looked

at are shown in Table 2. A tract that had a median income of $40,000 in 2000 would be considered middle

income, and if its median fell to $35,000 in 2010, it would be considered moderate income at that point. A more

detailed description of my methodology is provided in Appendix 1.

Table 2: Income Ranges by Neighborhood Type for 2000, 2010, and 2017

NEIGHBORHOOD TYPE RANGE 2000 2010 2017

Low Income 0-59.9% $0-$18,046 $0-23,631 $0-27,984

Moderate Income 60-99.9% $18,047-30,078 $23,632-39,386 $27,985-46,641

Middle Income 100-149.9% $30,079-45,117 $39,387-59,079 $46,642-69,961

Upper-Middle Income 150-199.9% $45,118-60,156 $59,082-78,772 $69,962-93,282

Upper Income 200%+ $60,157+ $78,773+ $93,283+

Citywide Median $30,078 $39,386 $46,641

I. NEIGHBORHOOD CHANGE IN BALTIMORE: AN OVERVIEW

This section will look at how each of the 11 neighborhood types has shifted since 2000—which types of

neighborhood have moved upward, which have moved downward, and which have stayed largely the same.

When I talk about upward and downward, I am talking about movement from one income range to another;

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 6

that is, when a census tract that was middle income in 2000 becomes an upper-income tract in 2017, or vice

versa. Upward movement is an indicator of potential gentrication, but does not in itself demonstrate that an

area is gentrifying. I explore additional factors that can point to gentrication in a later section of the report.

A. Citywide trends

Before looking at neighborhood categories, though, it is useful to take a quick look at the overall pattern of

change in the city of Baltimore since 2000, as shown in Table 3. Baltimore is a majority-minority city, with 62.1%

identifying as black or African American, 30.6% white, 0.26% American Indian and Alaskan Native, 3% Asian,

1.7% other races and 2.5% two or more races. Five and a quarter percent of the population identies as Latinx

of any race.

7

The city lost 30,000 people between 2000 and 2010, but its population has been roughly stable

since then. Specically, since 2000, the city has lost roughly 30,000 black residents and 30,000 white residents,

while gaining nearly 20,000 Latinx and 5,000 Asian residents. Since 2010, however, Baltimore has lost nearly

10,000 black residents, while its white population has stabilized, largely as a result of in-migration. Figure 1

shows the cumulative change by year from 2010 to 2017 for the city’s white and black populations.

Figure 1: Cumulative Population Change by Race 2010-2017

Baltimore has seen solid economic growth in recent years. Since 2010, the city has added nearly 20,000 jobs.

Household incomes in Baltimore have grown at a rate nearly 50% greater than the national rate over that

period; as a result, the median Baltimore household’s income has risen from 72% to 81% of the national

median. Income growth, however, has been greater among white households, whose incomes have grown at

more than double the rate of black households. As a result, the city’s income distribution has become more

polarized. In 2000, the median black household income was 71% of the median non-Latinx white household

income; by 2017, it had dropped to 49% of the median non-Latinx white household income.

7 Data from the 2014-2018 American Community Survey.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 7

Table 3: Citywide Trends

2000 2010

CHANGE

2000-2010

2017

CHANGE

2010-2017

CHANGE

2000-2017

Total Population (1) 651,154 620,538 -4.7% 619,796 -0.1% -4.9%

Black Population 418,951 399,121 -4.7% 389,222 -2.5% -7.1%

Latinx Population 11,061 22,821 +106.2% 30,729 +34.7% +177.8%

White Non-Latinx

Population

201,566 173,972 -13.7% 170,916 -1.8% -15.2%

Median Household

Income

$30,078 $39,386 +30.9% $46,641 +18.4% +55.1%

Average Annual Rate

of Change

+2.7% +2.4%

Black Median

Household Income

$26,202 $33,260 +26.9% $36,428 +9.5% +39.0%

White Median

Household Income

$37,113 $55,249 +48.9% $72,085 +30.5% +94.2%

% in Poverty 22.9% 21.3% -1.6% 22.4 +1.1% -0.5%

Homeowners 129,079 118,655 -8.1% 113,558 -4.3% -12.0%

Renters 128,117 119,737 -6.5% 126,233 +5.4% -1.5%

Homeownership

Rate

50.2% 49.2% 47.4%

Median Sales Price

(2)

$60,000 $91,000 +51.7% $106,000 +16.5 +76.7%

Sales Volume 10,211 6,647 -34.9% 10,433 +57.0% +2.2%

Median Monthly

Gross Rent

$498 $859 +72.5% 1,009 +17.5% +102.6%

Average Annual

Change

+$36 +5.6% +$21 +2.3%

SOURCE: 2000 Decennial Census, 2006-2010 and 2013-2017 American Community Survey, CoreLogic (sales price and volume)

(1) Breakdown of population by race/ethnicity does not include other racial groups and people indicating two or more racial

group membership.

(2) Median of sales by census tract

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 8

Sales prices in Baltimore, after collapsing with the foreclosure crisis and the Great Recession, have been slowly

recovering, but in most parts of the city, they are still well below national levels

8

or their 2007 peak. Since 2000,

rents have increased more rapidly than sales prices, and are now slightly above the national median rent. One

byproduct of this is that the percentage of Baltimore renters who are cost-burdened (spending over 30% of

their income for rent) went from 43% to 53% between 2000 and 2017. The most rapid rent rise and growth in

cost-burdened households took place between 2000 and 2010, and both have been largely stable since then.

Despite rising rents and aordable sales prices, Baltimore is losing homeowners. Since 2000, the city has lost

15,000 homeowners, and the homeownership rate has dropped from 50% to 47%, falling below 50% for the

rst time since 1930.

This short description makes clear that there is not one Baltimore. Baltimore is a large city, within which

many inconsistent, even conicting trends exist side by side. As a result, its neighborhoods are moving in

many dierent directions: some upward, some downward, and some staying much the same. This is to be

expected, but it reects an important overarching point about neighborhood change that is often overlooked.

Change is the norm. The majority of urban neighborhoods are engaged in an ongoing process of change.

Change can be upward, downward, or back again, driven by a complex mix of local, regional, and national

economic, demographic, and social trends and consumer preferences.

9

There is nothing inevitable either about

gentrication or neighborhood decline.

Table 4 shows how the distribution of the city’s neighborhoods has shifted since 2000 by race and economic

level. Reecting the national trends both with respect to a diminishing middle class and an increasing process

of “economic sorting” by income group, the number of neighborhoods in the middle in Baltimore has declined,

while the number of those at either end has risen. The number of upper-income areas has nearly tripled. This

shift can be seen vividly in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Change in Number of Baltimore Neighborhoods by Economic Level 2000 TO 2017

Low Moderate Middle Upper Middle Upper

15

10

5

0

-5

-10

-15

-20

8 The median price for existing homes in the United States during 2017 was approximately $246,000, or more than double the median price in

Baltimore.

9 For a comprehensive discussion of the dynamic processes of neighborhood change, and the factors involved, see my paper What Drives Neigh-

borhood Trajectories in Legacy Cities? Understanding the Dynamics of Change (2015), published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, and

available at https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/working-papers/what-drives-neighborhood-trajectories-legacy-cities.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 9

Table 4: Change in Number of Neighborhoods Over Time by Race and Economic Level

ALL NEIGHBORHOODS

2000 2010 2017

Low Income 22 28 32

Moderate Income 88 84 84

Middle Income 72 59 55

Upper-Middle Income 12 17 10

Upper Income 6 12 17

TOTAL

200 200 198

PREDOMINANTLY BLACK NEIGHBORHOODS

2000 2010 2017

Low Income 20 22 26

Moderate Income 59 63 62

Middle Income 31 27 16

Upper-Middle Income 2 1 0

Upper Income 0 0 0

TOTAL

112 113 104

PREDOMINANTLY WHITE NEIGHBORHOODS

2000 2010 2017

Low Income 0 1 0

Moderate Income 11 9 9

Middle Income 29 17 13

Upper-Middle Income 5 9 8

Upper Income 6 12 17

TOTAL

51 48 47

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 10

MIXED NEIGHBORHOODS

2000 2010 2017

Low Income 2 5 6

Moderate Income 18 12 13

Middle Income 12 15 26

Upper-Middle Income 5 7 2

Upper Income 0 0 0

TOTAL

37 39 47

When one looks at how neighborhoods have shifted by both economic level and race, however, a startling

contrast appears. Predominantly white neighborhoods tend to move upward in their trajectories, while

predominantly black neighborhoods tend to move downward. In 2000, there were 31 predominantly black

middle-income census tracts in Baltimore, or not quite 1 out of every 6 tracts. By 2017, there were only 16, or

half as many. As noted later, these neighborhoods did not gentrify, and many are in decline.

While the number of predominantly white middle-income census tracts also went down, the ones that changed

mostly moved upward. Indeed, the great majority of Baltimore’s gentrifying neighborhoods come from the

ranks of largely white formerly moderate- and middle-income neighborhoods. Indeed, a close look at the shift

in the distribution of predominantly white census tracts shows dramatic change: In 2000, only 1 out of 5 of

these tracts was upper-middle or upper income, but by 2017, over half fell into those categories.

This shift reects a major change in the makeup of Baltimore’s white population. While that population

was historically distributed fairly evenly across the full income spectrum from rich to poor, it is increasingly

becoming one of auent households. At the same time, the income distribution of the city’s black population

is moving in the opposite direction, reecting the out-migration of much of the city’s black middle class. Both

are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Citywide Change in Income Distribution of Households by Race 2000 TO 2017

Low Moderate Middle Upper Middle Upper

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

-10%

-20%

-30%

Black

White

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 11

The only economic segment of the city’s black population that is growing (either in share or numbers) is the

low-income population, while the only segment of Baltimore’s white population that is growing is the upper-

income population, reecting the dierential in- and out-migration taking place. Relative to their share of the

existing population, white in-migration to Baltimore is signicantly greater than black in-migration,

10

and as I

discuss later, white in-migration is disproportionately made up of well-educated (bachelor’s or higher degree)

and high-earning people in their 20s and 30s, who are clustering in a small number of areas in the city.

As I discuss in a later part of this report, a large part of the loss of white low-income households in Baltimore

is associated with gentrication. Between 2000 and 2017, the city lost 8,200 low-income white households,

of which 3,800 were in gentrifying census tracts. While some of this loss may potentially be considered

displacement, with these households moving elsewhere,

11

a signicant part of the loss may also be

attributable to mortality; over the same period, the number of white Baltimoreans over 65 dropped by

10,000, or nearly 30%.

B. Neighborhood trajectories

Given these citywide trends, what does it mean for individual neighborhoods? For an initial answer, I asked a

simple question: For each neighborhood in each of the 11 categories in 2000, where did they stand, in terms

of both race and economic level, in 2010 and 2017? Once I had the data, in order to present answers to that

question in a visually meaningful form, I color-coded each neighborhood based on its 2000 economic level and

racial distribution, and where it stood in both respects in 2010 and 2017.

Table 5: Economic Trajectories of Middle-Income Neighborhoods by Racial Category

NUMBER YEAR UP DOWN ALL CHANGE SAME

PREDOMINANTLY BLACK

31

2010 0 12 12 19

2017 0 18 18 13

MIXED

12

2010 2 1 3 9

2017 0 1 1 11

PREDOMINANTLY WHITE

28

2010 12 3 15 13

2017 15 4 19 9

10 For the period 2013 through 2017, the average annual number of white in-migrants was equal to 10% of the underlying white population base,

while the average annual number of black in-migrants was equal only to 4% of the underlying black population base. Average annual Latinx in-mi-

gration was nearly 12% of their population base. Latinxs were the only group with a net positive migration balance, although the white net loss

was far smaller than the black net loss.

11 Between 2000 and 2017, although the white population of Baltimore County dropped by over 50,000, the number of white residents over 65

increased by 3,200, suggesting the possibility of some migratory eects.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 12

Table 6 and Table 7 show the trajectories for predominantly white and predominantly black middle-income

neighborhoods (with median incomes between 100% and 150% of the citywide median income in 2000). The

color-coding key appears at the bottom of Table 6. By scanning across the three sets of columns, one can

quickly get a sense of the extent and direction of change in the cluster of census tracts from 2000 to 2010, and

from 2010 to 2017. Table 8 summarizes the data from the two tables below and also shows the trajectories for

the smaller number of racially mixed middle-income neighborhoods.

Table 6: Trajectories of Predominantly White Middle-Income Neighborhoods

by Black Population Share and Economic Level

2000

2010 2017

CATEGORY

% BLACK CATEGORY % BLACK CATEGORY % BLACK

24510010100 4% 24510010100 4% 24510010100 7%

24510010200 18% 24510010200 11% 24510010200 5%

24510010300 1% 24510010300 5% 24510010300 2%

24510010400 3% 24510010400 5% 24510010400 2%

24510010500 7% 24510010500 6% 24510010500 4%

24510020100 14% 24510020100 11% 24510020100 7%

24510030200 21% 24510030200 35% 24510030200 31%

24510120100 10% 24510120100 8% 24510120100 9%

24510130600 3% 24510130600 4% 24510130600 7%

24510130700 6% 24510130700 9% 24510130700 7%

24510130803 11% 24510130803 14% 24510130803 10%

24510130806 18% 24510130806 26% 24510130806 19%

24510230200 3% 24510230200 5% 24510230200 1%

24510230300 2% 24510230300 7% 24510230300 4%

24510240100 0% 24510240100 2% 24510240100 3%

24510240400 2% 24510240400 3% 24510240400 1%

24510250206 3% 24510250206 14% 24510250206 13%

24510250401 11% 24510250401 26% 24510250401 29%

24510260404 26% 24510260404 31% 24510260404 31%

24510260605 14% 24510260605 19% 24510260605 17%

24510260900 3% 24510260900 5% 24510260900 8%

24510270402 25% 24510270402 53% 24510270402 58%

24510270501 13% 24510270501 32% 24510270501 42%

24510270502 22% 24510270502 51% 24510270502 58%

24510270703 19% 24510270703 36% 24510270703 36%

24510271101 20% 24510271101 36% 24510271101 34%

24510272004 10% 24510272004 15% 24510272004 15%

24510272005 10% 24510272005 16% 24510272005 10%

0-29% African American Very Low Income (0-59% citywide median)

30-69% African American Low Income (60-99% citywide median)

70-100% African American Middle Income (100-149% citywide median)

Upper-Middle Income (150-199% citywide median)

Upper Income (200%+ citywide median)

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 13

The majority of Baltimore middle-income neighborhoods in 2000 were no longer middle-income

neighborhoods by 2017 (39 out of 71). But the trajectories of predominantly white and predominantly black

neighborhoods were very dierent. The great majority of predominantly white neighborhoods that changed

moved upward economically, while all of the predominantly black neighborhoods that changed moved

downward economically. Mixed neighborhoods showed much less change. By 2017, nine of the predominantly

white middle-income neighborhoods had become upper-income (200% or more of the city median income),

and another six had become upper-middle income. These are the neighborhoods in which the great majority

of Baltimore’s gentrication has taken place. The geographic distribution of predominantly black and

predominantly white middle neighborhoods, and their trajectories from 2000 to 2017, are shown in Map 1.

Table 7: Trajectories of Predominantly Black Middle-Income Neighborhoods

by Black Population Share and Economic Level

2000 2010 2017

24510080102 94% 24510080102 97% 24510080102 98%

24510090100 89% 24510090100 88% 24510090100 84%

24510090300 79% 24510090300 77% 24510090300 68%

24510090600 98% 24510090600 97% 24510090600 89%

24510130805 76% 24510130805 78% 24510130805 86%

24510150701 98% 24510150701 98% 24510150701 92%

24510150702 98% 24510150702 98% 24510150702 96%

24510150900 97% 24510150900 97% 24510150900 95%

24510151100 100% 24510151100 98% 24510151100 99%

24510160801 100% 24510160801 99% 24510160801 97%

24510160802 99% 24510160802 98% 24510160802 97%

24510200702 97% 24510200702 97% 24510200702 97%

24510250101 85% 24510250101 90% 24510250101 81%

24510250102 84% 24510250102 89% 24510250102 96%

24510260203 90% 24510260203 90% 24510260203 95%

24510260301 80% 24510260301 92% 24510260301 89%

24510260302 81% 24510260302 92% 24510260302 91%

24510260403 97% 24510260403 94% 24510260403 92%

24510270802 86% 24510270802 94% 24510270802 91%

24510270803 82% 24510270803 89% 24510270803 89%

24510270805 84% 24510270805 87% 24510270805 84%

24510270901 94% 24510270901 97% 24510270901 96%

24510270902 92% 24510270902 93% 24510270902 91%

24510270903 90% 24510270903 89% 24510270903 74%

24510271002 97% 24510271002 96% 24510271002 95%

24510271900 72% 24510271900 76% 24510271900 73%

24510280101 89% 24510280101 92% 24510280101 88%

24510280102 97% 24510280102 97% 24510280102 97%

24510280200 96% 24510280200 95% 24510280200 91%

24510280401 82% 24510280401 85% 24510280401 79%

24510280402 93% 24510280402 98% 24510280402 97%

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 14

Table 8: Economic Trajectories of All Other Neighborhoods by Racial Category

NUMBER YEAR UP DOWN ALL CHANGE SAME

LOW PREDOMINANTLY BLACK

19

2010 6 (note 1) NA (note 2) 6 13

2017 6 (note 1) NA (note 2) 6 13

MODERATE PREDOMINANTLY BLACK

59

2010 4 8 12 46

2017 3 14 17 42

MODERATE MIXED

18

2010 6 2 8 10

2017 6 3 9 9

MODERATE PREDOMINANTLY WHITE

11

2010 5 0 5 6

2017 5 0 5 6

UPPER-MIDDLE PREDOMINANTLY BLACK

3

2010 0 1 1 2

2017 0 3 3 0

UPPER-MIDDLE MIXED

4

2010 0 2 2 2

2017 0 4 4 0

UPPER-MIDDLE PREDOMINANTLY WHITE

5

2010 2 1 3 2

2017 2 1 3 2

UPPER PREDOMINANTLY WHITE

6

2010 NA (note 2) 0 0 6

2017 NA (note 2) 1 1 5

NOTES TO TABLE 8

(1) This “upward” movement, with the exception of one census tract, represents movement from low to moderate, which is not

necessarily a meaningful change in neighborhood conditions, but is likely to represent little more than the statistical phenomenon

known as regression to the mean. One tract did, however, move from low to middle over the study period; this census tract, which

roughly corresponds to the Greenmount West neighborhood, is unique in that respect, and will be discussed further later.

(2) Because the low-income and upper-income categories occupy the bottom and top of the category scale, and because the

methodology used to dene upward and downward movement is movement between categories, no downward movement for the

former, or upward movement for the latter, can take place.

During the same period, the black population living in what had been predominantly white middle-income

neighborhoods increased by 6,300, or roughly 72%, as seven of the census tracts in this category moved from

being predominantly white to racially mixed. Most of these tracts were in the northeastern part of the city, an

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 15

area to which large numbers of African American families have moved since 2000. By comparison, only one of

the 31 predominantly black middle-income census tracts saw any change in its racial distribution.

Table 8 shows the same information for the other neighborhood categories. The pattern that can be seen in

the middle-income neighborhoods generally holds true across economic levels. The majority of predominantly

black low- and moderate-income census tracts showed little or no change, but far more moderate-income

tracts moved downward, falling below 60% of the citywide median income between 2000 and 2017, than

moved upward. By contrast, nearly half of the predominantly white moderate-income tracts moved upward.

Similarly, all three of the largely black upper-middle income tracts in 2000 had moved downward by 2017.

Figure 4 summarizes and compares the overall neighborhood trend pattern for predominantly white and

predominantly black moderate, middle, and upper-middle neighborhoods, which could go either up or down,

from 2000 to 2017.

MAP 1: TRAJECTORIES OF MIDDLE NEIGHBORHOODS FROM 2000 TO 2017

Predominantly Black Neighborhoods Predominantly White Neighborhoods

272004

272003

271900

271801

271700

271501

130805

271600

151300

151200

151100

151000

280200

280302

150900

150800

150701

150702

150500

130400

130600

120700

130100

130200

090800

080101

270101

260303

260302

080102

080200

080302

260301

260202

260201

270102

260102

260203

260402

260403

130300

150400

150600

160802

280402

160700

280401

280403

280404

250101

250102

250103

200800

200702

200600

250206

210200

200500

200400

200200

190100

180100

180300

200100

180200

020200

030100

030200

020100

010500

261100

261000

080301

080400

070300

070200

070100

060200

060100

060300

010100

010200

190300

200300

040200

160600

160500

150300

150200

150100

140100

140200

280500

110100

120600

120300

120201

170200

170100

170300

160100

160200

160300

160400

140300

120500

090900

080600

080500

090700

090200

270903

090600

090500

090300

090100

090400

080700

080800

070400

040100

100100

100200

100300

120400

100200

250303

250301

250205

250207

250203

250204

250401

250402

250600

240100

010400

010300

060400

240400

230300

210100

220100

240200

020300

240300

230200

230100

260605

260604

260501

260700

260404

260401

260900

260800

250500

200701

160801

280301

271503

271400

271300

271200

271101

271102

271001

271002

270805

270804

270801

270802

270901

270902

270803

270600

270301

270302

270402

270502

270501

270703

270702

270701

270401

260101

270200

120100

120202

130700

130803

130806

130804

271802

272007

272006

280101

280102

272005

272004

272003

271900

271801

271700

271501

130805

271600

151300

151200

151100

151000

280200

280302

150900

150800

150701

150702

150500

130400

130600

120700

130100

130200

090800

080101

270101

260303

260302

080102

080200

080302

260301

260202

260201

270102

260102

260203

260402

260403

130300

150400

150600

160802

280402

160700

280401

280403

280404

250101

250102

250103

200800

200702

200600

250206

210200

200500

200400

200200

190100

180100

180300

200100

180200

020200

030100

030200

020100

010500

261100

261000

080301

080400

070300

070200

070100

060200

060100

060300

010100

010200

190300

200300

040200

160600

160500

150300

150200

150100

140100

140200

280500

110100

120600

120300

120201

170200

170100

170300

160100

160200

160300

160400

140300

120500

090900

080600

080500

090700

090200

270903

090600

090500

090300

090100

090400

080700

080800

070400

040100

100100

100200

100300

120400

100200

250303

250301

250205

250207

250203

250204

250401

250402

250600

240100

010400

010300

060400

240400

230300

210100

220100

240200

020300

240300

230200

230100

260605

260604

260501

260700

260404

260401

260900

260800

250500

200701

160801

280301

271503

271400

271300

271200

271101

271102

271001

271002

270805

270804

270801

270802

270901

270902

270803

270600

270301

270302

270402

270502

270501

270703

270702

270701

270401

260101

270200

120100

120202

130700

130803

130806

130804

271802

272007

272006

280101

280102

272005

Remained middle-income neighborhoods in 2017

Moved downward to low or moderate income

Moved upward to upper-middle or upper income

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 16

Figure 4: Summary of Neighborhood Trajectories From 2000 to 2017 by Race

To summarize, neighborhood change is a fundamental reality in Baltimore. Large numbers of neighborhoods

are moving both upward and downward economically, a few moved in one direction from 2000 to 2010,

and then reversed direction after 2010. Within the three middle-income categories—which represent the

great majority of Baltimore neighborhoods—nearly half changed category, either up or down, between 2000

and 2017.

In the next section, I will explore the signicance of these changes, and how they aect such factors as

population change, house values, and homeownership rates.

II. THE DIMENSIONS OF NEIGHBORHOOD CHANGE IN BALTIMORE

Economic change has powerful implications for other dimensions of neighborhood change. In this section, I

will explore how change aects two critical dimensions of Baltimore’s neighborhoods:

• Demographic change, including gains, losses, and population shifts by race, ethnicity,

and income; and

• Housing market change, including sales prices and sales volumes, and changes in

homeownership rates.

A. Demographic change

In this section, I will look at population shifts by race and by income, for the city’s African American, white, and

Latinx populations.

1. Black population change

Understanding trends aecting Baltimore’s African American population is particularly important for a number

of reasons. First, it is by far the city’s largest racial or ethnic group. Second, as I have shown, Baltimore’s

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 17

African American population has beneted proportionately less from the city’s strong but uneven revival

than Baltimore’s white population, exacerbating the racial wealth gap. Third, despite progress over the years,

African Americans face racialized disadvantage owing to structural racial and socioeconomic segregation, and

they are still more likely to experience discrimination and uneven treatment than others. Fourth, at least some

documents have treated population loss and gentrication-driven displacement as being eectively one and

the same, an assumption that needs to be critically examined.

As shown in Table 3, despite a natural increase (excess of births over deaths) of more than 20,000,

12

Baltimore’s

black population declined by nearly 20,000 from 2000 to 2010, and by an additional 10,000 from 2010 to 2017,

an overall decline of 7% since 2000. While I may not be able to answer the question of “why” with any precision,

the relationship between neighborhood trends and population change may suggest some answers.

Table 9: Change in Black Population 2000 to 2017 by 2000 Neighborhood Type

NEIGHBORHOOD

TYPE IN 2000

PREDOMINANTLY

BLACK

MIXED

PREDOMINANTLY

WHITE

NUMBER % NUMBER % NUMBER %

Low Income -10,716 -22.7%

Moderate Income -34,408 -18.8% -1,781 -7.1% +2,273 +52.8%

Middle Income -231 -0.2% +5,055 +21.7% +6,301 +72.4%

Upper-Middle

Income

+195 +3.5% +1,378 +20.9% -293 -21.4%

Upper Income +1,372 +84.7%

TOTAL CHANGE

45,160 -13.1% +4,652 +8.5% +9,653 +60.3%

Table 9 shows the gain or loss in black population by 2000 neighborhood type. Neighborhoods that were low-

income, predominantly black neighborhoods in 2000 lost 10,716 black residents, or nearly 1 out of 4 of those

living in those neighborhoods.

With minor exceptions, black population decline in Baltimore is the result of black households moving out of

predominantly black low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. That does not mean that there are no other

census tracts that saw declines in black population. There are a small number of such tracts, including some

that are gentrifying. But taken as a whole, movement out of predominantly black low- and moderate-income

neighborhoods unrelated to gentrication is driving black population decline in Baltimore. As I noted earlier,

this loss is disproportionately made up of middle- and upper-income households.

The table also shows a strong pattern of black households moving into neighborhoods that were either racially

mixed or predominantly white in 2000. These areas saw an increase of more than 14,000 in black residents

from 2000 to 2017. That inow, however, oset less than one-third of the outow from predominantly black

12 The positive natural increase balance is shrinking, however, as the number of births to black parents in Baltimore has dropped sharply since 2000

from 7,034 to 4,828 in 2017. This is a decline of 31%, far greater than the proportional decline in the overall population.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 18

low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. The others can be assumed to have left Baltimore City.

13

While

their destinations are not known, it is notable that over the same period, the black population of Baltimore

County grew by nearly 82,000 and that of Anne Arundel County by 26,000, growth that was likely to have been

fueled in part by out-migration from Baltimore City.

Map 2: Spatial Distribution of Black Population Gains and Losses 2000 to 2017

272004

272003

271900

271801

271700

271501

130805

271600

151300

151200

151100

151000

280200

280302

150900

150800

150701

150702

150500

130400

130600

120700

130100

130200

090800

080101

270101

260303

260302

080102

080200

080302

260301

260202

260201

270102

260102

260203

260402

260403

130300

150400

150600

160802

280402

160700

280401

280403

280404

250101

250102

250103

200800

200702

200600

250206

210200

200500

200400

200200

190100

180100

180300

200100

180200

020200

030100

030200

020100

010500

261100

261000

080301

080400

070300

070200

070100

060200

060100

060300

010100

010200

190300

200300

040200

160600

160500

150300

150200

150100

140100

140200

280500

110100

120600

120300

120201

170200

170100

170300

160100

160200

160300

160400

140300

120500

090900

080600

080500

090700

090200

270903

090600

090500

090300

090100

090400

080700

080800

070400

040100

100100

100200

100300

120400

100200

250303

250301

250205

250207

250203

250204

250401

250402

250600

240100

010400

010300

060400

240400

230300

210100

220100

240200

020300

240300

230200

230100

260605

260604

260501

260700

260404

260401

260900

260800

250500

200701

160801

280301

271503

271400

271300

271200

Northeast Triangle

271101

271102

271001

271002

270805

270804

270801

270802

270901

270902

270803

270600

270301

270302

270402

270502

270501

270703

270702

270701

270401

260101

270200

120100

120202

130700

130803

130806

130804

271802

272007

272006

280101

280102

272005

Loss of 1,500 or more

Loss of 1,000 to 1,499

Loss of 500 to 999

Gain of 1,500 or more

Gain of 1,000 to 1,499

Gain of 500 to 999

These trends have led to a dramatic shift in the spatial distribution of the city’s black population, as shown

in Map 2. Most tracts in East and West Baltimore are losing population, while most of the gain in black

population is taking place in an area that I call the “Northeast Triangle” shown on the map, including Loch

Raven, Overlea, Glenham-Belhar, Cedonia, and Frankford. That area saw its black population grow by 17,500

from 2000 to 2017.

13 The net out-migration was actually substantially larger than the reported population loss, since Baltimore’s black population maintained a positive

although gradually shrinking birth/death ratio throughout the period, resulting in a natural increase in the city’s black population since 2000 of

20,000 to 25,000. Notably, however, the number of births to black parents in Baltimore has dropped sharply since 2000 from 7,034 to 4,828 in

2017, a decline of 31%, far greater than the proportional decline in the overall population.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 19

The broad trend in Baltimore’s black population is the movement out of low- and moderate-income

neighborhoods, largely in East and West Baltimore, and movement toward the Northeast Triangle, but even

more so, outside Baltimore City entirely.

2. White and Latinx population change

As noted earlier, both black and white populations in Baltimore have declined by roughly 30,000 each since

2000. Since the city’s white population is much smaller than its black population, however, the proportionate

decline has been far greater, 15% compared to 7%. In contrast to the population decline in the city’s black

population, which is concentrated in predominantly black low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, white

population decline is widely distributed across most neighborhood types, except for small increases in

predominantly white upper-middle and upper-income tracts, as shown in Table 10. The increase in white

population in predominantly black moderate-income tracts is largely attributable to white population growth in

one census tract containing part of the Charles Village and Harwood NSAs near the Johns Hopkins campus.

Table 10: Change in White Population 2000 to 2017 by 2000 Neighborhood Type

NEIGHBORHOOD

TYPE IN 2000

PREDOMINANTLY

BLACK

MIXED

PREDOMINANTLY

WHITE

NUMBER % NUMBER % NUMBER %

Low Income -67 -2.3%

Moderate Income +475 +5.3% -4,231 -15.5% -7,667 -27.2%

Middle Income -1,746 -17.6% -6,921 -35.4% -7,947 -4.7%

Upper-Middle

Income

-661 -39.2% -2,616 -24.6% +305 +3.4%

Upper Income +387 +3.3%

TOTAL CHANGE

-1,999 -13,868 -14,922

Census tracts where the white population declined by more than 500 people greatly outnumbered those that

gained by a similar amount, as shown in Map 3. The greatest white population loss was in South Baltimore and

in the Northeast Triangle, while a handful of tracts showed signicant gain, principally downtown and around

the Inner Harbor.

As noted earlier, Baltimore’s white population has stabilized in recent years as a result of strong white

in-migration, visible both in census data and in homebuying activity. Ongoing replacement of the city’s

white population appears to be taking place, as long-time residents, many moderate- and middle-income,

leave or pass away, and are replaced by generally younger and more auent new arrivals, who are largely

concentrated in a smaller part of the city.

Baltimore’s Latinx population is the fastest growing segment of the city’s population, although only 5% of the

total. The area of greatest Latinx concentration is in Highlandtown and eastward, where they make up 30% to

45% of the total population of six census tracts. Overall, however, the city’s Latinx population is fairly dispersed;

only 25% of the city’s Latinx population lives in that area of Latinx concentration.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 20

Map 3: Spatial Distribution of White Population Gains and Losses 2000 to 2017

272004

272003

271900

271801

271700

271501

130805

271600

151300

151200

151100

151000

280200

280302

150900

150800

150701

150702

150500

130400

130600

120700

130100

130200

090800

080101

270101

260303

260302

080102

080200

080302

260301

260202

260201

270102

260102

260203

260402

260403

130300

150400

150600

160802

280402

160700

280401

280403

280404

250101

250102

250103

200800

200702

200600

250206

210200

200500

200400

200200

190100

180100

180300

200100

180200

020200

030100

030200

020100

010500

261100

261000

080301

080400

070300

070200

070100

060200

060100

060300

010100

010200

190300

190200

200300

040200

160600

160500

150300

150200

150100

140100

140200

280500

110100

120600

120300

120201

170200

170100

170300

160100

160200

160300

160400

140300

120500

090900

080600

080500

090700

090200

270903

090600

090500

090300

090100

090400

080700

080800

070400

040100

100100

100200

100300

120400

100200

250303

250301

250205

250207

250203

250204

250401

250402

250600

240100

010400

010300

060400

240400

230300

210100

220100

240200

020300

240300

230200

230100

260605

260604

260501

260700

260404

260401

260900

260800

250500

200701

160801

280301

271503

271400

271300

271200

Northeast Triangle

271101

271102

271001

271002

270805

270804

270801

270802

270901

270902

270803

270600

270301

270302

270402

270502

270501

270703

270702

270701

270401

260101

270200

120100

120202

130700

130803

130806

130804

271802

272007

272006

280101

280102

272005

B. Housing market change

Up to this point, I have focused on the population of Baltimore’s neighborhoods: how they are distributed

by income and race, and how populations have shifted from one part of the city to others since 2000. In this

section, I explore changes in Baltimore’s neighborhood housing markets—the dynamics of buying, selling,

and renting homes and apartments in the city’s neighborhoods. Before digging into the numbers, a brief

discussion of why housing markets—particularly the patterns of homebuying and selling—are so important to

understanding the dynamics of Baltimore’s neighborhoods may be useful.

While the housing market is far from the only thing that determines whether or not a neighborhood is a vital,

thriving community, it powerfully aects neighborhood outcomes. The demand for housing in a neighborhood

reects the extent to which people choose to live there rather than elsewhere, given their means and their

locational preferences. When people choose to buy a home in a particular neighborhood, they are making

a longer-term commitment to that neighborhood that often leads to behaviors that enhance neighborhood

vitality. Conversely, if people only live in a neighborhood because they lack other locational choices, and leave

if they can, their behavior is likely to reect that perspective and the neighborhood is likely to suer as a result.

Housing markets are a critical underpinning of neighborhood strength and vitality.

Loss of 1,000 or mor

e

Loss of 500 to 999

Gain of 1,000 or mor

e

Gain of 500 to 999

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 21

Where market demand is weak, prices are low and sales are few. Houses sit empty for a long time, and

those that sell are more likely to attract investors than owner-occupant buyers. Homeowners make fewer

improvements because they are unlikely to get their money back if they sell, while property owners are more

likely to fall behind on mortgage or property tax payments and let their houses go into tax sales or mortgage

foreclosure. All of those forces, in turn, often lead to houses eventually becoming abandoned, and in many

cases, economically unfeasible to rehabilitate and restore to use. Conversely, too rapid growth in demand

and prices can destabilize a neighborhood, encouraging speculation and undermining neighborhood stability

and cohesion.

This study is not a neighborhood-level market analysis of Baltimore. Such an analysis already exists, as for a

number of years, Baltimore City has commissioned regular analyses of small-area market conditions from the

Philadelphia-based Reinvestment Fund, and used those analyses to create neighborhood market typologies.

14

That information has been used to help design a number of city strategies, including the Vacants to Value

program. The purpose of this report is to look at the market dimensions of neighborhood change, and to

relate them to the shifts in household incomes and population movements described earlier.

To measure market strength and weakness, I look at three factors:

• Sales price

The price at which houses sell is the single most powerful measure of market strength or weakness.

This is particularly true in Baltimore, where most neighborhoods are dominated by row houses and

where many dierent neighborhoods contain houses of largely similar size, vintage, and construction.

A three- story row house can sell for over $500,000 in Bolton Hill, and a physically all-but-identical

15

one

may sell for less than one-tenth that price less than a mile to the west.

• Sales volume

For a housing market to be healthy, there have to be enough buyers to absorb the supply. If there are

too few buyers, properties may sit empty and ultimately be abandoned. Conversely, too many buyers

can overheat the market, or be a sign of speculation and ipping.

• Percentage of investor buyers

A high share of investor buyers in a neighborhood made up largely of single-family homes is a warning

sign. Not only is a reasonably high level of owner-occupants important for a stable neighborhood,

but the absence of owner-occupant buyers is also a sign that there are few people willing to make a

personal commitment to the neighborhood, as distinct from buyers who see the neighborhood purely

as a prot opportunity.

Finally, I look at change in the number of homeowners and the homeownership rate, which is an important

indicator of market conditions and neighborhood strength. Not only is there evidence that homeownership

may be an important factor in fostering neighborhood stability and community engagement, but

there is also evidence that declines—particularly if rapid—in homeownership can have a destabilizing

eect on neighborhoods.

16

14 These analyses are available at https://planning.baltimorecity.gov/maps-data/housing-market-typology.

15 Identical in the sense of having a similar architectural appearance, structural quality, square footage, and interior conguration. The Bolton Hill

row house is likely, however, to be in substantially better condition.

16 There is a substantial body of research on the impacts of homeownership. Much of the research is summarized in Lawrence Yun and Nadia Evan-

gelou, “Social Benets of Homeownership and Stable Housing,” published by the National Association of Realtors (2016) and available at https://

realtoru.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Homeownership-Stable-Housing.pdf. The evidence for family and behavior eects of homeowner-

ship is much stronger than the direct evidence of neighborhood eects, which to some extent must be inferred from the former. The eects of

declines in homeownership have been studied less, but one solid study is Chengri Ding and Gerrit-Jan Knapp, “Property Values in Inner-City Neigh-

borhoods: The Eects of Homeownership, Housing Investment and Economic Development,” Housing Policy Debate 13:4 (2003) 701–727. Clearly,

however, there is no generalizable “magic number” as to what a homeownership rate should be.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 22

As I will discuss later, these factors—particularly increases in sales price—are relevant to evaluating whether

and where gentrication may be taking place.

1. Real estate market dynamics

Baltimore shared in the housing bubble that consumed the United States from 2000 to 2007 and in the

subsequent bust. As Figure 5 shows, home sales prices in Baltimore more than doubled from 2000 to 2007,

going from $60,000 to $132,000, and then plummeted, falling to $75,000 by 2011. After at prices for a few

years, prices have started to recover, reaching a median of $106,000 in 2017.

17

As with other trends, the change

in prices was not experienced evenly across the city. Indeed, the most dramatic price phenomenon since 2000

has been the extraordinary variation in price change from one part of the city to another.

Figure 5: Citywide Median Sales Price by Year 2000 to 2017

Figure 6: Distribution of Sales Prices by Census Tract Relative to the Citywide Median

2000, 2010, and 2017

17 Preliminary 2018 data provided by CoreLogic shows a solid increase from the 2017 gures used in this report.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 23

What is striking about house prices in 2000 by census tract is how little price variation there was in Baltimore’s

housing market at the time. The lowest-priced census tract had a median that was more than half the citywide

median, and sales prices more than double the citywide median were found in only 15 tracts (7.5% of the total).

There were few tracts where the market was not functioning, and few upscale tracts where prices were high.

Prices in over 80% of the city’s census tracts fell in the relatively narrow range between 50% and 150% of the

citywide median price, as shown in Figure 6.

By 2010, this had already changed dramatically. The number of census tracts in the middle-income range had

dropped from 168 to 107, and the number continued to drop—to 84—from 2010 to 2017. More and more

tracts were at the bottom and the top of the home price range, and fewer and fewer were in the middle.

18

Another perspective on home sales price change comes by looking at the gain or loss in value in constant

dollars; that is, prices adjusted for ination.

19

From 2000 to 2017, the median sales price in Baltimore increased

by 24% in constant dollars, a respectable performance in light of the city’s boom-bust price cycle. Overall,

58% of the city’s tracts gained value, and 42% lost value. The change, however, was not evenly distributed.

Ordinarily, one would expect the gains and losses to be distributed along a bell-shaped curve,

20

with most of

the gains and losses clustered close to the middle. In actuality, as Figure 7 shows, the distribution was the

opposite. Few tracts changed only a little in house value. Far more gained a lot or lost a lot. Nearly a quarter of

the city’s tracts lost 30% or more in median house value in constant dollars, while over a quarter gained more

than 50% in value, and 1 out of 7 tracts saw their median house value in constant dollars more than double.

This is perhaps the single most vivid illustration of the economic polarization that has taken place in Baltimore

over the past two decades.

Figure 7: Distribution of Sales Price Change in Constant Dollars

2000 to 2017 (Number of Census Tracts)

18 For the statistically minded, the standard deviation of sales prices went from $42,417 in 2000 to $85,844 in 2010, and $103,056 in 2017.

19 For purposes of calculating ination, I used the change in the Consumer Price Index, which increased by 42.1% from June 2000 to

June 2017.

20 This distribution is so common that it is also referred to as a “normal distribution.”

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 24

This polarization relates closely to the racial composition of the neighborhood. As Figure 8 shows, 3 out of 5

predominantly white census tracts saw house prices increase by more than 50% in constant dollars, compared

to 2 out of 5 racially mixed, and only 1 out of 10 largely black tracts. Conversely, house prices declined by 20%

or more in nearly half of all predominantly black tracts, compared to less than 1 out of 5 mixed and 1 out of 12

predominantly white tracts. It is also strongly linked to the distribution of population losses and gains.

This has two powerful implications for the future of Baltimore’s predominantly black neighborhoods. First, it

has led to massive loss of wealth for many of the city’s black homeowners, for whom home equity typically

represents the greater part of their overall household wealth. Second, because stability and potential

appreciation in house value are an important consideration in homebuying decisions, it discourages

homebuyers, whether black or white, from buying homes in these neighborhoods. There is strong evidence,

with a handful of exceptions, that this is currently taking place.

Figure 8: Percentage Distribution of Sales Price Change from 2000 to 2017

by Racial Composition of Census Tract

The pattern is similar, but somewhat more complicated, for sales prices and sales volumes by both the

racial and income category of the census tract. Starting with the proposition that the average turnover in

an existing pool of residential properties typically runs 6% to 7% per year,

21

and allowing room for annual

uctuations, suggests that an annual volume of home sales in the range of 5% to 8% of the existing houses

in a given neighborhood (the “sales ratio”) can be considered the “Goldilocks” range—not too cold, and not

too hot. Ratios signicantly below that level are likely to lead to property deterioration, and in many cases

abandonment, as movers are unable to nd buyers or renters to replace them.

22

21 See, e.g., F.J.Fabozzi, The Handbook of Mortgage-Backed Securities, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill (2005); M. Piazzesi and M. Schneider, “Housing and

macroeconomics,” Handbook of Macroeconomics, 2, Elsevier, 2016: 1547-1640.

22 In a neighborhood where a signicant amount of new construction or substantial rehabilitation of houses for sale is taking place, the Goldilocks

range will be potentially signicantly higher, as the optimal number of buyers is the sum of those buying in the existing stock (i.e., 5% to 8% of

that stock) and the buyers of the new units coming on the market.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 25

Overall, the sales ratio for Baltimore in 2017 was 5.3%, meaning that residential sales in 2017 were equal to

5.3% of the city’s single-family housing inventory. While on the low side, it is within the Goldilocks range and

suggests that the housing market, on the whole, is functioning fairly well. As with other measures, however,

the citywide statistics mask considerable variation by neighborhood. Figure 9 shows the picture by census tract

racial and income category, while Table 11 shows detail for both sales prices and sales volumes for each of the

neighborhood categories.

Figure 9: Sales Ratios for Census Tracts by Racial and Income Category, 2017

The greatest market weakness is concentrated in predominantly black neighborhoods where the median

household income is at or below the citywide median—that is, low- and moderate-income neighborhoods.

Those neighborhoods have also seen signicant loss in house value in constant dollars. Black middle-

income neighborhoods are “hanging in” in terms of sales volumes, although barely, and seeing only nominal

appreciation in sales price. Adjusted for ination, house values in predominantly black middle-income

neighborhoods have been increasing at well under 1% per year since 2000, while predominantly white middle-

income neighborhoods saw an average increase of 4% per year over that period. Sales volumes in the city’s

mixed and predominantly white neighborhoods are consistently within the Goldilocks range, except for the ve

largely white upper-middle census tracts. On closer look, however, this reects unusually high volumes in two

areas: One is the Village of Cross Keys, and the second is to the west and south of the Inner Harbor, where a

great deal of new construction is taking place, pushing optimal sales volumes upward.

abell foundation

Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods | THE ABELL FOUNDATION 26

Table 11: Sales Prices and Sales Volumes by Neighborhood Category

NUMBER 2000 2010 2017

2017 SALES

RATIO

CHANGE

2000-2017

CHANGE IN

CONSTANT $$

LOW PREDOMINANTLY BLACK

Median price $52,450 $51,250 $69,125 +33%

-7%

Number of sales 445

191 297 2.2%

MODERATE PREDOMINANTLY BLACK

Median price $49,950 $61,000 $50,625

+1% -29%

Number of sales 1,934 1,621 1,831 3.2%

MODERATE MIXED

Median price $53,950 $84,225 $94,759 +76% 24%

Number of sales 914 746 1,006 6.3%

MODERATE PREDOMINANTLY WHITE

Median price $56,000 $145,000 $148,600 +165% 87%

Number of sales 591 474 751 7.5%

MIDDLE PREDOMINANTLY BLACK

Median price $62,000 $97,000 $101,550 +64% 12%

Number of sales 1,621 1,066 1,826 4.7%

MIDDLE MIXED

Median price $78,750 $120,375 $137,436 +75% 23%

Number of sales 982 590 890 5.9%

MIDDLE PREDOMINANTLY WHITE

Median price $86,375 $187,250 $237,250 +175% 93%

Number of sales 2,301 1,550 2,517 9.3%

UPPER-MIDDLE PREDOMINANTLY BLACK

Median price $75,975 $130,200 $146,950 +93% 36%

Number of sales 124 78 149 5.6%

UPPER-MIDDLE MIXED

Median price $76,000 $145,000 $156,000 +105% 41%

Number of sales 310 179 324 6.4%

UPPER-MIDDLE PREDOMINANTLY WHITE

Median price $124,000 $206,606 $296,675 +139% 68%

Number of sales 408 266 375 11.8%

UPPER PREDOMINANTLY WHITE

Median price $201,500 $426,250 $424,298 +111% 48%

Number of sales 545 322 442 6.8%

abell foundation