Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association

Volume 7 Number 2 Article 5

Fall 2019

Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia

Author A<liations Author A<liations

Elizabeth PullekinesElizabeth Pullekines, Front Street Clinic (Americorps)

Janani Rajbhandari-ThapaJanani Rajbhandari-Thapa, University of Georgia

Corresponding Author Corresponding Author

Janani Rajbhandari-Thapa (jr[email protected])

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/jgpha

Part of the Public Health Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Pullekines, Elizabeth and Rajbhandari-Thapa, Janani (2019) "Health Care Access by Weight Status in the

State of Georgia,"

Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association

: Vol. 7: No. 2, Article 5.

DOI: 10.20429/jgpha.2019.070205

Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/jgpha/vol7/iss2/5

This secondary data analysis is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Georgia Southern

Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association by an authorized

administrator of Georgia Southern Commons. For more information, please contact

Secondary Data Analysis

Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia

Elizabeth Pullekines, MPH

1

and Janani Rajbhandari-Thapa, PhD

2

1

Health Outreach Coordinator, Front Street Clinic (Americorps);

2

Department of Health Policy and Management, College of Public Health,

University of Georgia

Corresponding Author: Janani Rajbhandari-Thapa College of Public Health, University of Georgia 211 B Wright Hall (HSC), Athens, GA 30602 706-713-

2700 jrthapa@uga.edu

ABSTRACT

Background: Obesity continues to grow in prevalence in the United States and within the state of Georgia. Obesity is a risk

factor for many chronic and preventable diseases. As such, obese individuals have higher demand for health care services than

non-obese individuals. In addition, the health care system can play a role in preventing obesity and other conditions caused by

obesity.

Methods: This research follows the established positive relationship between health care use and access to health care services

through insurance coverage. The paper analyzes how the Affordable Care Act (ACA) affected insurance coverage and access to

health care services for obese and overweight individuals. A logistic regression was used on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor

Surveillance System.

Results: Results concluded that Georgia residents were less likely to have health insurance after the ACA was passed.

Significant association between weight status and health care services through insurance coverage was not found. The results

show that increased access to care including preventive services for obese and overweight post ACA is yet to be observed.

Conclusions: Findings present a need for lawmakers to develop policy to promote insurance enrollment for Georgian residents.

This is critical as the state sees an increase in overweight and obesity that are risk factor to many chronic disease conditions.

Keywords: Affordable Care Act, obesity, insurance, healthcare

https://doi.org/10.20429/jgpha.2019.070205

INTRODUCTION

Obesity prevalence has been increasing in the United States

(U.S.) since the 1990s. Nearly 38% of adults in the U.S.

were obese in 2014. This increasing trend in adult obesity

rates also applies to southern states. Though Georgia had the

third lowest obesity rate among southern states after Florida

(27.4%) and Virginia (29%), Georgia ranks 20

th

among all

the state in the U.S. in obesity and overweight rate. The

obesity rate in Georgia was 31.4% in 2016. The highest rate

among southern states was West Virginia, with 37.7%

(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Obesity

throughout the nation and the state is pervasive across

gender, ethnic origin, and socioeconomic status with some

variation in trend by race and ethnicity (Flegal et al., 2012).

For adults over the age of 20, men among all races, except

non-Hispanic black, were more likely to be overweight.

Women among all races were more likely to be obese then

men (Ogden et al., 2014). Further, obesity associated

comorbidities have been cited and reported in many

scholarly works (Guh et al., 2009). Obesity has also been

identified as a risk factor for heart disease and cancer, which

are among the top five preventable causes of death (Yoon,

2014). In Georgia, heart and vascular diseases, such as

stroke or hypertension, and some cancers are among the top

ten causes of deaths for adults aged 25 and older (Georgia

Department of Public Health, n.d.).

Furthermore, the cost impact of obesity on the U.S. health

care system is high. Annual cost of obesity was $190 billion

in 2005 (Cawley et al., 2012). In the state of Georgia alone

the direct and indirect costs of obesity was $2 billion in

2003 (Finkelstein et al., 2004). Chronic diseases that obesity

is a risk factor for, such as heart disease and diabetes,

account for $2.3 trillion in health care costs annually in

2008 dollars (Oschman, 2011). Obese individuals’ health

care utilization rates and associated costs was also higher

compared to non-obese individuals (Peterson and

Mahmoudi, 2015). The median increase in mean annual

healthcare costs were 12% for overweight and 36% for

obese individuals, compared to individuals at healthy weight

with highest percentage increase in medications, inpatient

care and ambulatory care (Kent et al., 2017). Furthermore,

studies have found that about 80% of heart disease, stroke,

and type 2 diabetes and 40% of cancers are preventable

(Gerteis et al., 2014). As such understanding factors

associated with prevention and treatment of obesity,

including access to health care, is critical. The focus of this

study is to explore access to health care by weight status.

38

Pullekines and Rajbhandari-Thapa: Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia

Published by Georgia Southern Commons, 2019

Health care services can play a role both in obesity

prevention and treatment. To prevent obesity, hospitals may

provide behavioral counseling (Katz and Faridi, 2007).

Hospitals can also engage in outreach activities or have

obesity prevention programs such as skill building classes

for their service area. Healthcare organizations might also

have spaces in their facility for small fitness centers or a

healthful cooking teaching kitchen. This would be an

important step towards addressing obesity as simple

nutrition and weight counseling has been proven to be

effective at reducing weight (McAlpine & Wilson,

2007).While this idea has been considered in the past, there

have been many barriers such as access to care by obese

individuals to seriously offering treatments such as obesity

and nutrition counseling to tackle the obesity issue in the

hospital setting (Kraschnewski et al., 2013; McAlpine &

Wilson, 2007). To treat obesity, health care providers can

utilize more invasive treatment options such as bariatric

surgery (Gloy et al., 2013). Hence it is important to

understand the health care coverage for obese and

overweight individuals.

Utilization of the available obesity prevention and treatment

services depends on obese individuals’ access to health care

through insurance coverage. Health care access and

utilization is dependent on insurance coverage and insurance

coverage measures access to health care. In a study

exploring societal and individual determinants of medical

care insurance coverage was found to affect health care

utilization (Milbank, 2005). In a study, 90% of low-income

uninsured adults stated costs as the main barrier to health

care (Hoffman and Paradise, 2008). Over 40% of uninsured

adults, compared to 18% of insured adults, did not have a

routine checkup in a two-year time frame (Hoffman and

Paradise, 2008). Furthermore, obesity has been found to be

associated with lower socioeconomic status (Newton et al.,

2017). Cost of care is a significant barrier to accessing

health care. As such, utilization of health care is affected by

insurance coverage. Insurance assist individuals in reducing

their health care expenses. Routine checkups are important

to maintain health and avoid long-term health care costs.

Because obesity is an identified risk factor for several

comorbid conditions, access and utilization of health care in

association with weight status is even more critical.

This study aims to analyze how the Affordable Health Care

(ACA) impacted access to health care coverage and health

care coverage by weight status among adults in the state of

Georgia. We hypothesize that those with a higher weight

status would be more likely to obtain health care coverage

and access to health care would have increased post ACA.

Increased access to health care would allow individuals with

more than normal weight to reduce the costs of services that

they receive, regardless of whether it is due specifically to

their weight or a disease associated with excess weight.

METHODS

Data

This study used the state of Georgia’s Behavioral Risk

Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data from 2005

through 2015. BRFSS is a telephone-based survey

conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC); the deidentified dataset is made publicly

available on their website at www.cdc.gov

. The survey

collects data on U.S. residents at the state level regarding

resident’s health behavior, chronic health conditions, and

preventative services utilization. Data also includes access

to healthcare, weight status, and metropolitan status. BRFSS

collects responses from participants in all 50 states,

Washington D.C., and territories and provides state

identifiers making studies possible at the state level.

Furthermore, this study was possible as the data set for

Georgia included the same questions regarding the variables

of interest from 2005 to 2015. Further this research does not

constitute Human Subjects Research as per the institution’s

policy as it is based on publicly available deidentified

secondary dataset. The survey question and response option

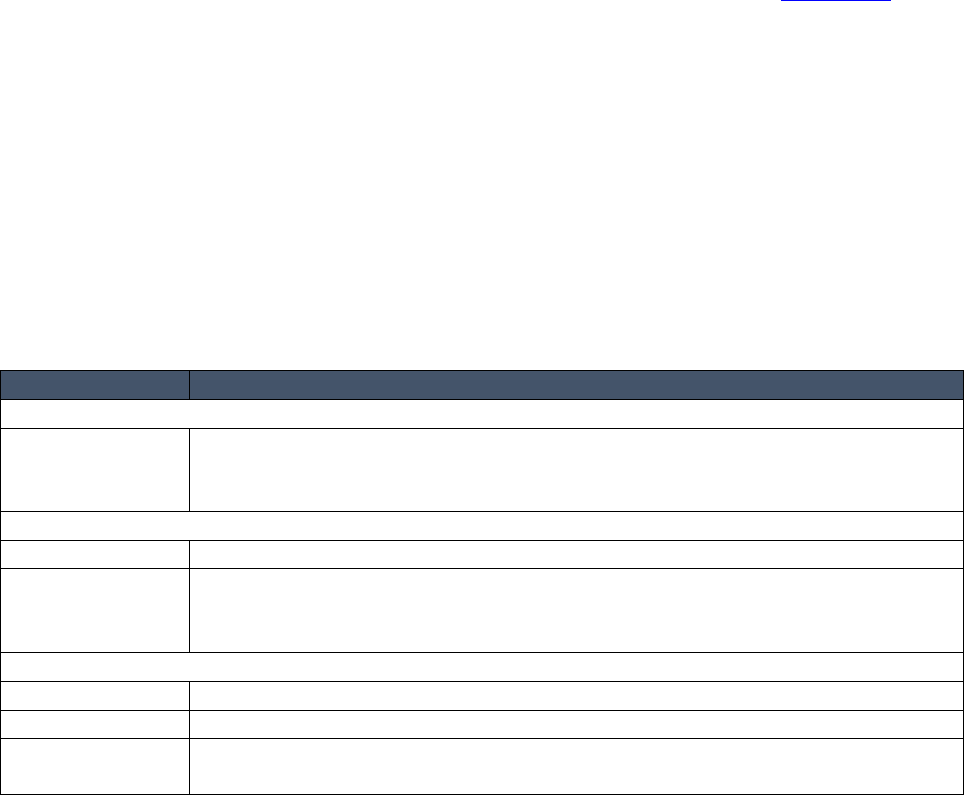

for each variable are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Data from 2005-2015 BRFSS Surveys

Data

Survey question and response options in BRFSS

Dependent variable

Have insurance

coverage

Do you have any kind of health care coverage, including health insurance,

prepaid plans such as HMOS, or governmental plans such as Medicare, or

Indian Health Service? Yes/ No

Explanatory variables

BMI categories

Underweight or normal (≤ 24.9)/ Overweight (25-29.9)/ Obese (≥30)

Before and after

the Affordable

Care Act

2005-2015 (1 if 2005 through March 2010, 0 if April 2010 through 2015)

Confounding variables

Gender

Male/ Female

Age

18-24/ 25-34/ 35-44/ 45-54/ 55-645/ 65 and above

Race

White/ Black/ American Indian or Alaskan Native (Native)/ Asian/ Native

Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (Hawaiian) / Other race

39

Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association, Vol. 7, No. 2 [2019], Art. 5

https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/jgpha/vol7/iss2/5

DOI: 10.20429/jgpha.2019.070205

Data

Survey question and response options in BRFSS

Income

Less than $15,000/ $15,000 to $24,999/ $25,000 to $34,999/ $35,000 to

$49,999 /$50,000 or more

Education

Did not graduate high school/ Graduated high school/ Attended college or

technical school/ Graduated from College or Technical School

Metropolitan

status (MSA)

In the center city of an MSA/ Outside the center city of an MSA, but inside

the county containing the center city/ Inside a suburban county of the MSA/

In a MSA that has no city center/ Not in an MSA

Employment

status

Employed for wages/ Self-employed/ Out of work for 1+ year/ Out of work

for less than 1 year/ A homemaker/ A student/ Retired/ Unable to work

General health

Would you say that in general, your health is?

Excellent/ Very Good/Good/Fair/Poor

Have poor

physical health

Now thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and

injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health

not good? # of days/ None

Have poor

mental health

Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression,

and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was

your mental health not good? # of days/ None

Poor health

preventing usual

activities

During the past 30 days, for about how many days did poor physical health or

mental health keep you from doing your usual activities, such as self-care,

work, or recreation? # of days/ None

Checkup

About how long has it been since you last visited a doctor for a routine

checkup? Within past year/ Within past 2 years/ Within past 5 years/ 5 or

more years ago/ Never

Unable to

receive care due

to cost

About how long has it been since you last visited a doctor for a routine

checkup? [A routine checkup is a general physical exam, not an exam for a

specific injury, illness, or condition.]

This study assessed access to health care by weight status in

Georgia using insurance coverage as a proxy to health care

access, which affects utilization of obesity prevention and

treatment-oriented health care services. Data from the 2005

to 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

surveys were compiled to create a time series data and

logistic regression analysis was used. This study tested if

obese and overweight individuals have a higher likelihood

of having insurance coverage given the established

relationship between higher weight status and chronic

diseases. The model was controlled for confounding from

socio-demographic variables such as age, income,

education, employment status, and race along with

metropolitan status. Further, prior to 2010, most states

allowed insurance companies in the individual market to

deny individuals’ health insurance coverage based on health

status and allowed rates to be set based on health status (Lee

et al., 2010). Obesity was identified as a risk factor for

several disease as early as the 1990s (Must et al., 1999). As

a result, obese individuals may have been denied health

insurance services due to health conditions that list obesity

as a risk factor. The enactment of the Affordable Care Act

(ACA) in 2010, prohibited insurance companies from

denying individuals coverage due to pre-existing conditions.

The study accounts for the post ACA period due to its

potential impact on insurance coverage. Period after ACA is

also important to identify because post ACA individuals

with insurance coverage would have increased access to

preventive health care such as annual wellness check. This

is important with respect to obesity and it could potentially

help identify weight issues earlier rather than later when it

has caused other health problems or treatment are costlier.

Data analysis

Data from each year from 2005 to 2015 were downloaded

and compiled to develop a time series data. Pregnant women

were excluded from the study. Variables were adjusted to

accommodate variations in answers to the same questions in

different years. For example, the years 2011-2015 had four

categories for BMI (underweight, normal, overweight, and

obese), while 2005-2010 only used three. Underweight and

normal weight in 2011-2015 were combined to match data

from previous years. A logistic regression model was used

to predict insurance coverage as a proxy to health care

access by weight status and enactment of the Affordable

Care Act. As such, having any health care coverage served

as the dependent variable. This was measured by the

responses to the question “Do you have any kind of health

care coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans

such as HMOs, or governmental plans such as Medicare or

Indian Health Service?” The explanatory variables of

interest included year and weight status. Year variable was

40

Pullekines and Rajbhandari-Thapa: Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia

Published by Georgia Southern Commons, 2019

dichotomized to before and after the Affordable Care Act

was passed. Prior to the Affordable Care Act ranged from

2005 to March 2010. After the Affordable Care ranged from

April 2010 to 2015. This was due to the ACA being signed

into law on March 23, 2010 (“H.R. 3590-11

th

Congress”,

2010). The dataset is rich and allowed adjustment for

confounding from sociodemographic variables such as

gender, age, race, income, and education. In addition, the

model controlled for other potential confounders such as

employment status, geographical location (metropolitan

status), general, physical and mental health, and the state of

being in poor health. Education may influence knowledge of

what kind of coverage is available. Employment status can

influence where individuals receive health insurance and the

type of coverage they receive. Metropolitan status (MSA)

can influence the number of insurance providers individuals

have access to. For example, there may be more providers in

a city center than a rural community. The data were

analyzed using STATA version 14.2.

RESULTS

The demographics of the overall sample and the insured and

uninsured categories within this sample is shown in Table 2.

The highest proportion of respondents in each category were

white followed by African-American. The insured

population had a slightly higher percentage (71%) of white

individuals and slightly lower percentage of African-

American respondents (22%) compared to 63% and 28%

within the uninsured category. About 36% of the overall

population had a college degree followed by high school or

some college education. The percentage of college

graduates within the insured was highest (36%), while the

percentage of high school graduates was highest (35%)

within uninsured category. Proportion of male respondents

were higher than female. Most individuals in all three

populations were between the ages of 35 and 44. About 32%

of the respondents in all categories were from a suburban

county. Highest proportion (35%) of the uninsured lived

outside an MSA. Highest proportion (43%) of respondents

in the insured category had an income above $50,000. Only

20% of the uninsured population had an income over

$50,000. For the uninsured population, having an income

between $15,000 and $24,999 made up the largest

percentage, at about 32%. In terms of employment,

employed for wages make up the largest percentage for all

three categories.

Table 2. Respondent’s demographics (%)

Overall

n=12,437

Insured

n=10,855

Uninsured

n=1,582

Race

White

70

71

63

Black

23

22

28

Hispanic

3

3

4

Asian

1

1

1

American Indian

1

1

1

Other Race

1

1

1

Multiracial

1

1

2

Education

< High school

11

10

18

High school graduate

27

25

35

Some college

27

26

27

College graduate

36

39

20

Gender

Male

54

54

58

Female

46

46

42

Age

18-24

5

4

9

25-34

17

16

22

35-44

27

26

30

45-54

14

13

18

55-64

17

17

18

≥ 65

20

23

3

Metropolitan status

Not in MSA

29

28

35

MSA suburban county

32

32

31

MSA county

12

13

11

MSA city center

26

27

23

Income

< $15,000

13

11

24

41

Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association, Vol. 7, No. 2 [2019], Art. 5

https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/jgpha/vol7/iss2/5

DOI: 10.20429/jgpha.2019.070205

Overall

n=12,437

Insured

n=10,855

Uninsured

n=1,582

$15,000-24,999

19

17

32

$25,000-34,999

12

12

13

$35,000-49,999

14

15

11

≥ $50000

43

46

20

Employment status

Employed for wages

46

47

40

Self-employed

8

7

13

No work > 1 year

3

2

11

No work < 1 year

3

2

7

Homemaker

6

6

6

Student

3

2

4

Unable to work

12

11

13

Retired

20

22

5

Year

Before ACA (Jan 2005-Mar 2010)

55

55

57

After ACA (Apr 2010-Dec 2015)

45

45

43

Table 3 shows the demographics of respondents by weight

status. Most of the respondents in each of the three

categories reported being white, followed by African-

American. In terms of education, most overweight and

normal or underweight respondents reported having a

college degree, while most obese respondents reported

having a high school degree. About 49% of obese

respondents reported after the Affordable Care Act was

passed. This was higher than overweight and normal or

underweight. Obese and overweight individuals were more

likely to report being male, 54% and 63%, respectively.

About 55% of normal or underweight individuals reported

being female. Most respondents in each category reported to

be between the ages of 35 and 44. About 32% of obese,

33% of overweight, and 31% of normal or underweight

reported living in a suburban county of a metropolitan city.

Most individuals in each weight status reported having an

income of over $50,000. Nearly 45-50% of respondents in

each weight category reported to be employed for wages.

About 16% of obese reported being unable to work. This

was about twice the percentage for each of the other two

weight status.

Table 3. Respondents’ demographics by weight status (%)

Obese

(n=4,186)

Overweight

(n= 4,367)

Normal

(n=3,884)

Race

White

65

73

74

Black

30

21

18

Hispanic

3

2

3

Asian

0

1

2

American Indian

1

1

1

Other Race

1

1

1

Multiracial

1

1

1

Education

< High school

12

10

10

High school graduate

30

26

23

Some college

28

26

25

College graduate

30

38

42

Gender

Male

54

63

45

Female

46

37

55

Age

18-24

3

3

9

25-34

15

16

21

35-44

27

25

29

42

Pullekines and Rajbhandari-Thapa: Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia

Published by Georgia Southern Commons, 2019

Obese

(n=4,186)

Overweight

(n= 4,367)

Normal

(n=3,884)

45-54

17

15

10

55-64

20

19

12

≥ 65

19

23

19

Metropolitan Status

Not in MSA

32

29

26

MSA suburban county

32

33

31

MSA county

11

13

13

MSA city center

24

25

29

Income

< $15,000

15

10

12

$15,000-24,999

21

18

18

$25,000-34,999

12

12

11

$35,000-49,999

14

14

14

≥ $50000

37

46

45

Employment Status

Employed for wages

45

47

45

Self-employed

7

8

9

No work > 1 Year

4

3

4

No work < 1 Year

3

3

3

Homemaker

4

5

8

Student

2

2

4

Unable to work

16

10

9

Retired

19

23

19

Year

Before ACA (Jan 2005-Mar 2010)

51

56

59

After ACA (Apr 2010-Dec 2015)

49

44

41

Table 4 shows the health status of respondents. Most

respondents in the overall (34%) and insured categories

(33%) were overweight. For the uninsured population, obese

individuals had the highest percentage (36%). About 87% of

the overall population reported having insurance. Finally,

most individuals reported having a checkup within the past

year. Most respondents reported being in good health across

all categories. About 71% of the overall and insured

population and 68% of the uninsured population reported

having poor physical health in the last 30 days. About 62%

of the overall population and 60% of the insured reported

having poor mental health in the past 30 days. Seventy one

percent of the uninsured respondents reported poor mental

health.

Table 4. Respondents’ health status (%)

Overall

n=12,437

Insured

n=10,855

Uninsured

n=1,582

Weight status

Obese

33.66

33.29

36.16

Overweight

35.11

35.63

31.54

Normal

31.23

31.07

32.3

Have insurance coverage

87.28

100

0

Unable to receive care due to cost

20.95

16.55

51.14

Time Since Last Checkup

Never

0.97

0.81

2.09

Within the past year

74.41

77.52

53.03

Within 2 years

11.06

10.58

14.41

Within 5 years

6.65

5.73

12.96

5 or more years

6.91

5.36

17.51

43

Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association, Vol. 7, No. 2 [2019], Art. 5

https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/jgpha/vol7/iss2/5

DOI: 10.20429/jgpha.2019.070205

Overall

n=12,437

Insured

n=10,855

Uninsured

n=1,582

General health

Excellent

12.14

12.42

10.24

Very good

28.83

29.33

25.41

Good

30.19

29.96

31.8

Fair

18.37

17.84

22

Poor

10.46

10.45

10.56

Have poor physical health

71.02

71.52

67.64

Have poor mental health

61.71

60.34

71.11

Poor health preventing usual activities

41.61

41.02

45.64

Table 5 shows the respondents’ health status by weight.

Overweight respondents had the highest percentage (89%)

of being insured followed by obese (86%) and normal or

underweight (87%). About 26% of obese individuals

reported they were unable to receive care due to costs. All

three weight categories mostly reported having had a

checkup within the past year. Obese had the highest

percentage while normal or underweight had the lowest. In

terms of general health, about 35% of obese respondents

reported being in good health. About 31% of overweight

and 33% of normal or underweight individuals reported

their health as very good. A higher percentage of obese

individuals reported their health as being fair or poor than

the other two weight categories. Obese were also less likely

to report their general health as being excellent. About 77%

of obese individuals reported having poor physical health in

the past month. Normal or underweight respondents were

the most likely to reported having poor mental health in the

past month. Finally, about 47% of obese reported having

poor health preventing them from engaging in their usual

activities.

Table 5. Respondents’ health status by weight (%)

Obese

(n=4,186)

Overweight

(n= 4,367)

Normal

(n=3,884)

Have insurance coverage

86.34

88.57

86.84

Unable to receive care due to cost

25.9

17.66

19.31

Time Since Last Checkup

Never

0.72

1.03

1.18

Within the past year

77.16

73.87

72.04

Within 2 years

9.82

11.15

12.31

Within 5 years

6.24

7.01

6.69

5 or more years

6.07

6.94

7.78

General health

Excellent

5.47

12.18

19.28

Very good

22.17

31.3

33.24

Good

34.5

30

25.77

Fair

24.7

16.78

13.34

Poor

13.16

9.73

8.37

Have poor physical health

76.59

70.74

65.35

Have poor mental health

61.47

59.45

64.52

Poor health preventing usual

activities

47.37 38.68 38.7

The results of the logistic regression are shown in Table 6,

reported are the odds ratio for having insurance coverage by

weight status, and before and after ACA with controls for

potential confounding from gender, education level, income

level, employment status, age, metropolitan status, race,

checkup, unable to receive care due to cost, general health,

have poor physical health, have poor mental health, and

poor health preventing usual activities. No significant

44

Pullekines and Rajbhandari-Thapa: Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia

Published by Georgia Southern Commons, 2019

differences were seen in the likelihood of having insurance

plan by weight status. Finally, after the Affordable Care Act

was passed, Georgians were 21% less likely to have

insurance (p<0.01). Confounding from race was not

significant for any race category. However, there were

significant confounding from education status. Those with

less than high school education were 41% less likely to have

health insurance than college graduates (p<0.001) followed

by high school graduate (32% less likely, p<0.001) and

some college (21% less likely, p<0.001). Males were 53%

less likely to have health insurance than females (p<0.001).

Each age category under the age of 65 were at least 81%

less likely to have insurance than those over 65 (p<0.001).

Those between 18 and 25 were the least likely (89%,

p<0.001) to have insurance coverage. Likelihood of having

insurance increased with age. Individuals living outside of

the MSA were 17% less likely to have insurance than those

within a city center (p=0.026). Income revealed similar

trends to age, higher the income more likely an individual

would be insured. Those with an income less than $15,000

were 73% less likely (p<0.001) than those with an income

higher than $50,000 to have insurance. Regarding

employment, those employed for wage were 37% less likely

to have insurance (p=0.003). Students were 48% less likely

to have insurance than retired (p=0.003). Homemakers and

those with no work for less than one year were just under

45% less likely to have insurance (p<0.001). Self-employed

and those without work for over a year were 71% and 74%,

respectively, less likely to have insurance than the retired

population (p<0.001). Individuals unable to receive care due

to cost were 43% less likely to have insurance (p<0.001).

Those who have had a longer time since their last checkup

were less likely to have insurance (p<0.001). The other

health related measures were not significant.

Table 6. Odds ratio from logistic regression

Odds ratio

p value

95% CI

BMI

Obese

1.05

0.564

0.90-1.21

Overweight

1.12

0.125

0.97-1.31

Normal or underweight

1.00

Year

After ACA

0.79

<0.001

0.69-0.89

Before ACA

1.00

Education

< High school

0.59

<0.001

0.48-0.74

High school graduate

0.68

<0.001

0.57-0.81

Some college

0.79

0.007

0.66-0.94

College graduate

1.00

Gender

Male

0.47

<0.001

0.41-0.55

Female

1.00

Age

18-24

0.11

<0.001

0.07-0.16

25-34

0.14

<0.001

0.09-0.20

35-44

0.14

<0.001

0.10-0.20

45-54

0.18

<0.001

0.13-0.25

55-64

0.19

<0.001

0.13-0.26

≥ 65

1.00

Metropolitan status

Not in MSA

0.83

0.026

0.71-0.98

MSA suburban county

0.88

0.112

0.75-1.03

MSA county

0.97

0.795

0.78-1.20

MSA city center

1.00

Income

< $15,000

0.27

<0.001

0.22-0.34

$15,000-24,999

0.32

<0.001

0.27-0.39

$25,000-34,999

0.50

<0.001

0.40-0.62

$35,000-49,999

0.66

<0.001

0.54-0.81

≥ $50,000

1.00

Employment status

45

Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association, Vol. 7, No. 2 [2019], Art. 5

https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/jgpha/vol7/iss2/5

DOI: 10.20429/jgpha.2019.070205

Odds ratio

p value

95% CI

Employed for wages

0.63

0.003

0.46-0.85

Self-employed

0.29

<0.001

0.21-0.40

No work > 1 Year

0.26

<0.001

0.18-0.37

No work < 1 Year

0.36

<0.001

0.25-0.52

Homemaker

0.38

<0.001

0.26-0.56

Student

0.52

0.003

0.34-0.81

Retired

1.00

Health

Unable to receive care due to cost

0.37

<0.001

0.33-0.42

Time Since last checkup

0.76

<0.001

0.72-0.81

Race had no significant confounding effect, hence not reported in the table.

DISCUSSION

This study examines access to health care by weight status

in the state of Georgia using insurance coverage as a proxy

to health care access and thus utilization of obesity

prevention and treatment-oriented health care services.

Findings suggest that obese and overweight residents did

not have a higher likelihood of having insurance coverage

compared to non-obese individuals. The direction of the

coefficients was as expected, but not significant. Further,

Georgia residents were less likely to be insured after the

Affordable Care Act was passed. This was not entirely

expected due to the individual mandate outlined by the

reform law. This result was different from another study that

found that there was a 27.4% decrease in uninsured rates

between 2010 and 2015. This study found larger decreases

in uninsured rates for the three southern states that expanded

Medicaid in 2014 than those that did not (Garret. &

Gangopadhyaya, 2016). However, this study did not look at

weight status. These differences could be attributed to

Georgia lawmakers not expanding Medicaid. Several

Georgians may have fallen in the coverage gap and were

unable to afford insurance coverage. Living outside of an

MSA may have influenced this association, as nearly 30%

of respondents lived outside these areas. This population

was the second largest of the overall respondents. This

region was the only area that had a statistically significant

association with having less insurance than those living in a

city center. Such, rural urban gap in health care safety net

program has also been previously documented in the state of

Georgia (Minyard et al., 2016).

Obesity has been found to be associated with certain

socioeconomic status (SES). One meta-analysis found that

overall, those with lower SES were more likely to be obese

(Newton et al., 2017). Though there are individual variation,

there is a predictable pattern. Studies have found that those

with higher incomes and higher education levels were more

likely to be insured (Swinburn, 2011 and Hong et al., 2016).

This is consistent with our findings. This could be because

those with higher incomes may find insurance more

affordable and would be more willing to purchase it. Several

factors can influence the relationship between education and

insurance status. Educated adults are less likely to be

unemployed, as well as have higher incomes. More

educated individuals may have the knowledge or social

networks to help navigate healthcare more easily. They may

also live in areas where insurance is more accessible than

less educated individuals (Zimmerman et al., 2015). Males

having less insurance is consistent with other research (Day

et al., 2015; Long et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2016; Dahlen,

2015). Each study reported similar numbers and that the

percentage of men and women having insurance grew closer

after the ACA was passed. Similar percentages of men and

women having Medicare and private insurance were found

(Day et al., 2015).

The findings of this study have policy implications at the

state level. Obese and overweight individuals of Georgia not

having a higher likelihood of having insurance coverage is

concerning. It is further concerning that there was decrease

in insurance coverage after the Affordable Care Act. Health

insurance can help reduce the costs of health care services

for patients, including obese patients who are at a higher

risk for diseased condition. This would especially be

beneficial for lower income individuals who were found to

be less likely to have insurance. Therefore, Georgia

lawmakers should consider expanding Medicaid. Efforts

also should be made to increase the insurance rates for those

who would qualify for employer-sponsored or Marketplace

based plans as well. This could increase the number of

individuals, including obese and overweight individuals,

with health insurance, as well as the number of individuals

who have access to healthcare. Special attention is also

needed to increase insurance coverage among individuals

with obesity and overweight in future policies developed to

promote insurance coverage.

In addition to increasing the number of insured individuals,

expansion of insurance coverage, specifically to low income

population through Medicaid can positively influence

economic activity and employment rates at the state level.

One report noted that 70,343 jobs could be created statewide

in Georgia because of Medicaid expansion, mostly in the

healthcare sector. Real estate, food services, transit and

ground passenger transportation, employment services,

wholesale trade businesses, and construction would also see

an increase in employment. Yearly economic output would

increase by an average of $8.2 billion because of these new

jobs. State and local tax revenue would be increased by an

average of $276.5 million, annually (Custer, 2013).

Another report noted that an investment of 1% of the state

46

Pullekines and Rajbhandari-Thapa: Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia

Published by Georgia Southern Commons, 2019

budget could create $65 billion in new economic activity

over 10 years, as well as create over 56,000 jobs throughout

Georgia. State and local tax revenue would increase by $2.2

billion over the same 10-year period (Sweeney, 2013).

CONCLUSIONS

This study aimed to look at the association between weight

status and insurance coverage among Georgia residents and

how the ACA influenced this association. Results

concluded that obese and overweight residents in the state of

Georgia did not have a higher likelihood of having

insurance coverage compared to non-obese individuals. This

conclusion is concerning as the literature is well established

that obese and overweight individuals are at a higher risk for

several preventable chronic disease conditions. Further,

having access to healthcare is crucial to this population for

obesity prevention and treatment. Suggested that Georgia

residents were less likely to have health insurance after the

ACA was passed. This study demonstrates the need to

promote insurance for Georgia residents.

Acknowledgements

There was no funding for this data.

Statement of Student-Mentor Relationship: The lead author for

this report is Elizabeth Pullekines, a Master of Public Health

student in the Department of Health Policy and Management,

College of Public Health, University of Georgia. Dr. Janani

Rajbhandari-Thapa, the senior author, served as her mentor.

References

Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an

instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2012;

31(1):219-230. Doi: 10.1016/j.jealeco.2011.10.003.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). BRFSS

Prevalence & Trends Data. Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html

.

Custer, W.S. (2013, February). The Economic Impact of Medicaid

Expansion in Georgia.

Healthcare Georgia Foundation. Retrieved from

http://www.healthcaregeorgia.org/uploads/file/Georgia_Medicai

d_Economic_Impact.pdf.

Dahlen, H.M. (2015). “Aging Out” of Dependent Coverage and the

Effects on US Labor Market And Health Insurance Choices.

American Journal of Public Health, Supplement 105(55), S640-

S650.

Day, J.C., O’Hara, B., Taylor, D. (2015, September 16). Another

Difference Between the Sexes-Health Insurance Coverage: Men

Lag Behind Women in Health Insurance Coverage.

Census.

http://blogs.census.gov/2015/09/16/another-difference-

between-the-sexes-health -insurance-coverage-3/.

Finkelstein, E.A., Fiebelkorn, I.C., Wang, G. (2004). State-Level

Estimates of Annual Medical Expenditures Attributable to

Obesity. Obesity Research, 12(1), 18-24. Doi:

10.1038/oby.2004.4.

Flegal, K.M., Carroll, M.D., Kit, B.K., Ogden, C.L. (2012,

February 1). Prevalence of obesity And trends in the distribution

of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA,

307(5), 491-7. Doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39.

Georgia Department of Public Health. Community Health Needs

Assessment Dashboard. Online Analytical Statistical

Information System. Retrieved from

https://oasis.state.ga.us/CHNADashboard/Default.aspx

Garrett, B., Gangopadhyaya, A. (2016, December). Who Gained

Health Insurance Coverage Under the ACA, and Where Do

They Live? The Urban Institute. Retrieved from

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/86761/2001

041-who-gained-health-insurance-coverage-under-the-aca-and-

where-do-they-live.pdf

Gerteis, J., Izrael, D., Deitz, D., LeRoy, L., Ricciardi, R., Miller,

T., Basu, J. (2014, April). Multiple Chronic Conditions

Chartbook. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Retrieved from

https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/

prevention-chronic- care/decision/mcc/mccchartbook.pdf.

Gloy, V., Briel, M., Bhatt, D.L., Kashyap, S.R., Mingronge, G.,

Bucher, H.C., Nordmann, A.J.

(2013, October 22). Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical

treatment for obesity: a

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled

trials. BMJ. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f5934.

Guh, D.P., Zhang, W., Bansback, N., Amarsi, Z., Birmingham,

C.L., Anis, A.H. (2009, March 25). The incidence of co-

morbidities related to obesity and overweight: A systematic

Review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458

-9-88.

Hoffman, C., Paradise, J. (2008, June). Health Insurance and

Access to Health Care in the United

States. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Doi:

10.1196/annals.1424.00

Hong, Y.R., Holcom, D., Bhandari, M., Larkin, L, (2016).

Affordable care act: comparison of Healthcare indicators among

different insurance beneficiaries with new coverage

Eligibility. BMC Health. Doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1362-1.act.

H.R. 3590-111

th

Congress: Patient Protection and Affordable Care.

(2010). Retrieved from

https://govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr3590.

Kraschnewski, J. L., Sciamanna, C. N., Stuckey, H. L., Chuang, C.

H., Lehman, E. B., Hwang, K. O., . . . Nembhard, H. B. (2013).

A silent response to the obesity epidemic: decline in US

physician weight counseling. Med Care, 51(2), 186-192.

doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182726c33

Katz, D.L., Faridi, Z. (2007). Health Care System Approaches to

Obesity Prevention and Control. In Kumanyika, S.,

Brownson, R.C. (Eds.), Handbook of Obesity Prevention: A

Resource for Health Professionals (285-316). New York, NY:

Springer Science + Business Media, LLC.

Kent, S., Fusco, F., Gray, A., Jebb, S.A., Cairns, B.J., &

Mihaylova, B. (2017, May 22). Body Mass index and healthcare

costs: a systematic literature review of individual participant

Data studies. Obesity Reviews. Doi: 10.1111/obr.12560.

Lee, J.S., Sheer, J.L.O., Lopez, N., & Rosenbaum, S. (2010, July-

August). Coverage of Obesity Treatment: A State-by-State

Analysis of Medicaid and State Insurance Law. Public

Health Report, 125(4): 596-604. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nigh.gov/pmc/articles/PMC288611/

.

Long, S.K., Stockley, K., Shulman, S. (2011). How Gender Gaps

in Insurance Coverage Access to Care Narrowed under Health

Reform? Findings from Massachusetts. American

Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 101(3), 640-644.

Doi: 10.1257/aer.101.3640.

McAlpine, D. D., & Wilson, A. R. (2007). Trends in obesity-

related counseling in primary care: 1995-2004. Med Care, 45(4),

322-329. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000254575.19543.01

Milbank, Q. (2005, December). Societal and Individual

Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States.

The Milbank Quarterly. Doi: 10.1111/j.1469-

0009.2005.00428.x.

47

Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association, Vol. 7, No. 2 [2019], Art. 5

https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/jgpha/vol7/iss2/5

DOI: 10.20429/jgpha.2019.070205

Minyard, K., Parker, C., Butts, J. (2016). Improving rural access to

care: Recommendations for Georgia’s health care safety net.

Journal of Georgia Public Health Association, 5(4), 387-396.

Retrieved from

https://www.gapha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/14-5.412-

Improving-rural-access-to care.pdf.

Must, A., Spadano, J., Coakley, E.H., Field, A.L., Colditz, G. &

Dietz W.H. (1999, October 27). The Disease Burden

Associated With Overweight and Obesity. The JAMA Network.

Retrieved from

http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/192030

Newton, S., Braithwaite, D., Akinyemiju, T.F., Xiao, G. (Ed.)

(2017, May 16). Socio-economic status over the Life course

and obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One,

12(5). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177151.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. (2014). Prevalence of

childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012.

JAMA. 311(8):806-814. Doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732

Oschman, J.L. (2011, April). Chronic Disease: Are We Missing

Something? Journal of Alternative Complementary Medicine,

17(4): 283-285. Doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0101.

Peterson, M.D., Mahmoudi, E. (2015). Healthcare Utilization

Associated with Obesity and Physical Disabilities. American

Journal of Preventative Medicine, 48(4): 426-435.

Doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.007

.

Sweeney, T. (2013, February). The Dollars and Sense of

Expanding Medicaid in Georgia: Medicaid Expansion Yields

Great Return for Georgia’s Economy. Georgia Budget

& Policy Institute. Retrieved from

https://gbpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Cover-Georgia1.pdf.

Swinburn, B.A., Sacks, G., Hall, K.D., McPherson, K., Finegood,

D.T., Moodie, M.L., Gortmaker, S.L. (2011, August 27). The

global obesity pandemic: shaped by global

Drivers and local environments. Lancet, 378(9793), 804-14.

Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1.

Yoon, P.W., Bastian, B., Anderson, R.N., Collins, J.L., Jaffe,

H.W., & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

(2014, May 2). Potentially preventable deaths from the five

leading Causes of death – United States, 2008-2010. Morbidity

and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(17), 369-74. Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6317a1.ht.

Zimmerman, E.B., Woolf, S.H., Haley, A. (2015, September).

Population Health: Behavioral and Social Science Insights:

Understanding the Relationship between Education and Health.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved from

https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-

tools/population health/zimmerman.html.

© Elizabeth Pullekines, and Janani Rajbhandari-Thapa. Originally published in jGPHA (http://www.gapha.org/jgpha/) October 25, 2019. This is

an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No-Derivatives License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original work ("first published in the Journal of the Georgia Public Health Association…") is properly cited with original URL and bibliographic

citation information. The complete bibliographic information, a link to the original publication on http://www.gapha.jgpha.org/, as well as this

copyright and license information must be included.

48

Pullekines and Rajbhandari-Thapa: Health Care Access by Weight Status in the State of Georgia

Published by Georgia Southern Commons, 2019