FOR THE LOVE OF THE WHITE MAN'S GAME:

AN ANALYSIS OF RACE IN CONTEMPORARY MAJOR LEAGUE

BASEBALL

_______________

A Thesis

Presented to the

Faculty of

San Diego State University

_______________

In Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Master of Arts

in

Liberal Arts and Sciences

_______________

by

Weston Robertson

Spring 2022

iii

Copyright © 2022

by

Weston Robertson

All Rights Reserved

iv

DEDICATION

To Mom, Dad, and Grandma. Without you, none of this would be possible.

v

“It’s like déjà vu all over again.”

― Yogi Berra

vi

ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS

For the Love of the White Man’s Game: An Analysis of Race in

Contemporary Major League Baseball

by

Weston Robertson

Master of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences

San Diego State University, 2022

It is supposed to be common knowledge that Major League Baseball’s “color line”

was broken by Jackie Robinson. Leading up to that historic event, baseball team owners had

collectively forged an unwritten agreement to maintain that their league was to be played by

white players. However, players such as Moses Fleetwood Walker, Charlie Grant, and Rube

Foster challenged the unofficial enforcement of the color-line in the major leagues and

consequently faced varied forms of public backlash, all before Robinson’s tumultuous debut

in April 1947. And Negro League teams and barnstorming clubs experienced significant

popularity and financial success. This paper will seek to recognize the largely unknown

history of “color line” breakers prior to Robinson as well as to address the status of race-

based discrimination in baseball in the post-Robinson era, leading up to today. Drawing on

works by Rob Ruck, Adrian Burgos Jr., David J. Leonard, as well as from contemporary

journalism, I will compare and contrast racial divides in Major League Baseball across nearly

a hundred years; I will explore how Ben Chapman’s verbal berating of Robinson in 1947

compares to the Fenway crowd’s hateful jeers towards Adam Jones in 2017, and how MLB

exploitation of talent from the Negro Leagues served as a precursor to the way it currently

“acquires” and compensates international players. Proving the well-known adage that

“history tends to repeat itself,” this thesis demonstrates the persistence of both covert and

overt discriminatory practices employed by major league baseball regarding race, and

decisively argues that discriminatory practices, transactions, and environments are still

prevalent in the league today. This research contributes to an ongoing dialogue regarding the

“white way” to play baseball, decreasing participation rates by players of color, and systemic

discrimination in the hiring and gatekeeping practices of Major League Baseball.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. vi

LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................... viii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... ix

CHAPTER

1 HISTORIOGRAPHY ....................................................................................................3

Introduction ..............................................................................................................3

II. Nineteenth Century Black Baseball ....................................................................4

III. Latinos & Passing: A Tracing Of Early Public Reception ..............................17

IV. Afro-Latinos & Rising Latino Prominence in MLB .......................................20

V. Consequences of Integration .............................................................................23

VI. Conclusion .......................................................................................................26

2 CONTEMPORARY MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL ...............................................29

Introduction ............................................................................................................29

II. Socioeconomic Inequalities in American Baseball Development ....................30

III. Problematic International Signing and Development Systems ........................33

IV. Racially Coded Descriptors of Black and Latin Players .................................41

V. “Unofficial Rules” Upholding the “White Way” to Play ................................46

VI. Major League Baseball Today .........................................................................56

VII. Conclusion ......................................................................................................62

REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................65

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

PAGE

Figure 1. Image displaying a fallen soldier juxtaposed with a Black pitcher. .........................13

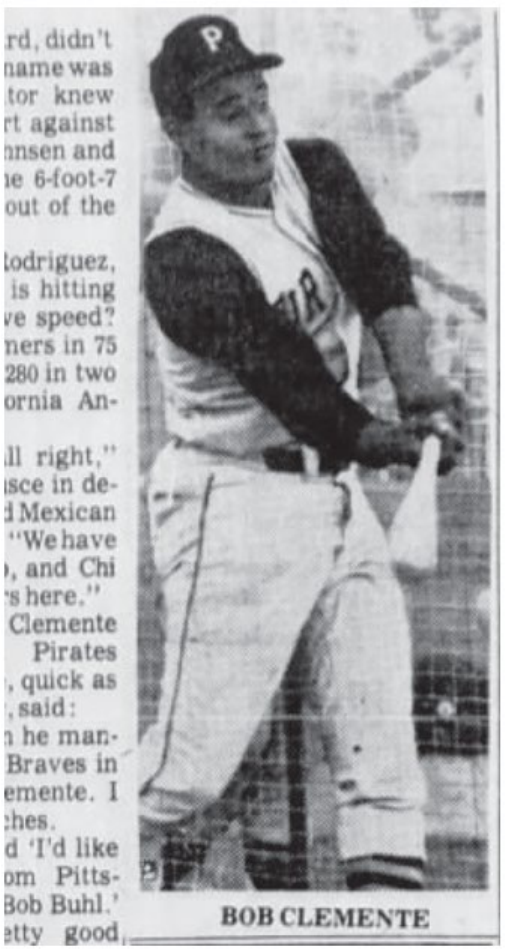

Figure 2. Roberto Clemente, 1970. ..........................................................................................22

Figure 5. MLB: The Show 21 cover athlete Fernando Tatis Jr. ..............................................39

Figure 6. Sports Illustrated magazine “The Cardinal Way.” ...................................................50

Figure 7. Tim Anderson, throwing his bat in celebration. .......................................................52

ix

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First, I am extremely gracious of Dr. David Cline, Dr. Michael Dominguez, and Dr.

David Kamper for their time, effort, and energy in pushing this across the finish line.

Second, to all my friends and family that have unconditionally supported me throughout my

academic journey: I could not have done it without each one of you.

Third, a special thank you to all my other teachers, faculty, and professors that have

significantly impacted me in various ways. Thank you in particular to Mrs. Christina Garrity,

Dr. Paul Minifee, Prof. Blaine Malcolm, Dr. Edith Frampton and Dr. Raj Chetty for showing

me the way.

1

INTRODUCTION

In the time following George Floyd’s death at the hands of the police in May 2020,

many American institutions, including the predominant sports in America, faced a period of

self-reckoning regarding race, racial injustices, and police brutality (Tracy). Race, a socially

constructed concept referring to different types of human bodies and their physical

characteristics, has significant consequences largely due to existing institutional power

structures. Publicly at least, over the past two years Major League Baseball, for example, has

begun to pay more attention to its racial inequities such as its increasing inaccessibility for

members of lower-income or non-white communities, its player acquisition and development

systems in international contexts, its racially-charged descriptors and covert stereotypes, its

overt enforcement of arbitrary rules and on-field etiquette, and its inherent racism regarding

hiring, heckling, and historically-rooted partiality for Whiteness. When applying these

concepts to my argument about race in contemporary Major League Baseball, I am

specifically referring to people belonging to African American or Black ethnic groups and

Mexican, Dominican, Cuban, Venezuelan, Puerto Rican, or other Latin ethnic groups. All

these racial dynamics and policies have long, unique, and complex histories that must be

examined in order to put more recent claims to change into appropriate context.

Chapter One begins with the recognition of African Americans in Major League

Baseball before Jackie Robinson and note the varied successes that early Negro League

teams earned, while also beginning an exploration of player of color demographics that

included not only African Americans but a long history of Latinx participation in the sport.

Although the history of the Black baseball pioneers has been well explored elsewhere, we

must start with this story, as it forms the backbone for what will come later. In this first

section, I relied heavily on publications from the Society of Baseball Research (SABR),

Ryan A. Swanson’s 2014 book, When Baseball Went White: Reconstruction, Reconciliation,

and Dreams of a National Pastime, electronic records from both the Negro League Baseball

eMuseum and National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Patricia H. Hinchey’s 2018

analysis of The Souls of Black Folk, originally written by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1903. Next, I

trace the representation of Latinos in Major League Baseball using Adrian Burgos Jr.’s 2007

book, Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line, and identify the

relationship between light-skinned Latinos and their reception from players and the public.

2

Their history of “passing” requires contrary context on darker-skinned Afro-Latinos who

were barred due the color of their skin, such as Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso, Roberto Clemente,

and to a more contemporary extent, Sammy Sosa. Then I examine the consequences of Major

League Baseball’s integration using Rob Ruck’s 2012 book, Raceball: How the Major

Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game, August Wilson’s 1985 play, Fences, and Joe

Posnanski 2007 book, The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck O'Neil's America, to

fully contextualize the harm that integration caused to Negro League players, teams, and

surrounding Black communities. I also utilize William C. Rhoden’s 2006 book, Forty Million

Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete, and Dave Zirin’s 2009

book, A People's History of Sports in the United States: 250 Years of Politics, Protest,

People, and Play to demonstrate the perceived invalidity—and unfair raiding of talent

from—the Negro Leagues after Jackie Robinson’s integration in 1947. Lastly, I recognize the

roots of persisting or peripheral artifacts of current systemic racial discrimination in MLB’s

history of holding and sometimes transgressing the color-line.

Chapter Two consolidates and examine the listed racial inequalities in contemporary

Major League Baseball and confirms the existence of persisting ‘color-lines’ originating

from its pre-integration period. It does so within the context of recent work in decolonial

theory and decolonial methodology employed by Ethnic Studies scholars such as Walter

Mignolo, Santiago Castro-Gomez, and Stewart Hall, and tied closely to postcolonial theorists

like Edward Said. Also applied are ideas about constructions of the White identity,

essentialism, positionality, and structuration theory, as well as the theory of “racial covering”

established by legal scholar Kenji Yoshino. More specifically, I will draw upon Walter

Mignolo’s concept of epistemological disobedience to highlight the rejection of hegemonic

Whiteness, Eurocentric epistemology, and upstanding “unwritten rules'' as decolonizing acts

by Black and Latin players. Additionally, I will be addressing said issues within Major

League Baseball (MLB)—the professional baseball organization located predominantly in

the United States—and its affiliate developmental academies located in the Dominican

Republic. This argument applies to baseball as institutionalized through the Major League

and does not address or examine systemic issues inherent in the sport of baseball, the bat-

and-ball game played worldwide in various competitive, expressive, or structural formats.

This distinction is of vital importance.

3

CHAPTER 1

HISTORIOGRAPHY

I

NTRODUCTION

In one swift announcement on December 16, 2020, Major League Baseball officially

recognized the Negro Leagues as “Major Leagues,” solidifying a reclassification that was

long-overdue (@MLB). This elevation of status meant that the Negro Leagues’ statistical

achievements and championship titles at last became integrated into MLB’s history, although

some historians and baseball aficionados had long recognized them previously. Players, too,

like Dizzy Dean and Willie Sellars, as well as sportswriters Wendell Smith and Sam Lacy,

knew that Negro League baseballers were good enough to play in the segregated Major

Leagues (Condon). Contemporaneous practice proved as much, as coveted athletes like

Satchel Paige earned more money than their white counterparts (Ruck 81-3). Despite sport

operating on the premise of “equality of opportunity, sportsmanship, and fair play,” and

previous attitudes of integration and positive public popularity on the backs of Jack Johnson,

Jesse Owens, and Joe Louis, Black professional athletes still ‘failed to receive the recognition

and monetary reward they deserved’ (Spivey 148).

In this Introduction, I will chart the current historiography, discussing published

works such as Rob Ruck’s Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin

Game, Adrian Burgos Jr.’s Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line.

Additionally, I reference William C. Rhoden’s Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall,

and Redemption of the Black Athlete and Ryan A. Swanson’s When Baseball Went White:

Reconstruction, Reconciliation, and Dreams of a National Pastime, among others, to fully

acknowledge and contextualize the presence of African Americans in Major League Baseball

prior to Jackie Robinson. I explore the consistent contention with the color line through

publications associated with the Society of Baseball Research (SABR), published archives

from both the Negro League Museum and the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and recorded

4

in personalized accounts sourced from Dave Zirin’s book, A People's History of Sports in the

United States: 250 Years of Politics, Protest, People, and Play, Joe Posnanski’s book, The

Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck O'Neil's America, and Ballers of the New

School: Race and Sports in America by Thabiti Lewis. I explore how this historiography

depicts how African Americans and Latino players, like Josh Gibson and Silvio García,

navigated an era of organized baseball defined by lack of opportunities and the firm

enforcement of racial discrimination. The color line—as explained in works by Ruck, Burgos

Jr., and others—has always been a point of historical contention and cultural significance for

African Americans and Latinos, and reports of its demise have sometimes been issued far too

soon.

II. NINETEENTH CENTURY BLACK BASEBALL

First, it is important to establish that before Jackie Robinson, Black baseball players

competed in baseball at all levels, including in organized, non-segregated professional

baseball. While baseball was primarily a white-collar activity before the American Civil War,

the intermingling and recreational time in wartime camps facilitated the spread of baseball’s

popularity to all socio-economic groups—including different races. Yet the “people’s game,”

as it was called, was equally reflective of American segregationist practices. Ryan A.

Swanson, in his book, When Baseball Went White: Reconstruction, Reconciliation, and

Dreams of a National Pastime, states that in 1892, the same year that the federal government

abolished slavery in Washington D.C., the district ‘enacted a series of black codes that

limited the social freedom of free blacks’ (11). As Washington D.C. popularized in the

nineteenth century, so did baseball. Swanson records that in 1866, public spaces such as the

White Lot (a field south of the White House, previously existing where The Ellipse Park is

today), were bustling with baseball and cricket games (14-5). The closer one played to the

White House signified a geographical proximity to political power, but nearly ten years later,

in 1874, The White Lot became segregated, further gatekeeping baseball from black athletes

like Octavius Catto and Charles Douglass (“The White Lot”).

However, in 1866, only a year after the conclusion of the Civil War, Octavius Catto

founded a baseball team at the only Black high school in Philadelphia (Institute for Colored

Youth), and within five years, they officially established themselves as the Pythian Base Ball

5

Club and began playing white teams (Casway, “Octavius Catto…”). “In 1867 the ‘Pyths,’ as

they were sometimes called, strengthened themselves by recruiting players from other black

teams. Under Catto’s captaincy the team played 13 games in 1867. They went 8–3, and two

games have no known results. One white reporter was so impressed by the Pythians, he

described them as a ‘well behaved gentlemanly set of young fellows … [who] are rapidly

winning distinction in the use of the bat’” (Casway, “Sept. 3…”). The Pythians were part of

several regionally organized baseball teams, like the South Brooklyn Excelsiors and the

Olympic Base Ball Club of Washington D.C. that formed after the American Civil War; and

despite their low-stakes exhibitions, these teams created a path for future Black competitive

teams. In October of that year, Catto and his Pythian Base Ball Club applied to join the

Pennsylvania Association of Amateur Base Ball Players but were denied due to their race.

The Pythian Base Ball Club believed that “black credibility and acceptance could be

promoted by competing against “our white brethren” on a baseball diamond” (Casway,

“Octavious Catto”). And yet, because of the racial power systems during Reconstruction, the

White baseball accepted the Pythian’s challenge because they believed the “black teams

would play inferior ball” (Casway, “Octavious Catto”). The Pythian’s faced an important

challenge: win and prove their validity as athletes and as individuals or lose and endure more

discrimination on account of their race. Despite the underlying socio-political pressure,

Pythian games became a community event; there were organized pre-game and post-game

festivities, women and wives prepared picnics and banquets, as well as “gatherings that

allowed black leaders to meet and discuss issues that transcended the ball fields” (Casway,

“Octavious Catto”). During the same—and arguably best—1867 season for the Pythians,

abolitionist Fredrick Douglass ‘attended and watched his son play third base for the

Washington D.C. club versus the Pythians’ (Casway, “Octavious Catto”). Baseball during

this period was intertwined with burgeoning civil rights activism as seen in this quote from

Swanson’s book: “Black baseball, in Washington D.C. and often elsewhere, exhibited the

blend of operational pragmatism and steely commitment to equality advocated by Frederick

Douglass” and often their participation embodied “autonomy, equality and opportunity”

(Walker). Using baseball as a vehicle for equality, in much the same way that they attempted

to participate in the American military, Black Americans created their own teams–and found

6

great, albeit short, success–despite nationwide racial hostilities and the foundations of a

‘color line’ in America’s national pastime.

Fredrick Douglass, in his life-long fight against slavery and segregation, was

“suspicious of sports” despite being an honorary member of his son’s team, the Mutual Base

Ball Club (Rhoden 47). His reason for this, as William C. Rhoden details in his 2006 book,

Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete, is that

“competition dulled the revolutionary inclination” in a way that kept slaves “semi-civilized,”

unfocused on emancipation and psychological liberation’ (47-8). Therefore, reinforcing why

his attendance in 1867 was particularly note-worthy. Rhoden offers an alternate perspective,

arguing that Douglass was too close-minded about sports and competition, arguing that

sports could, “for enslaved men in particular, became a ritual of reclaiming one’s manhood…

[and that] for many blacks, sports were similarly symbolic ways of physically transcending

the system of bondage, a space for freedom” (49). Despite his general pessimism about

sports, Douglass’s desegregationist ideologies resonated among Black baseball organizations.

Swanson, in his own book, writes, “In Charles Douglass’s baseball world, then, social

equality seemed to support the creation of strong, black-led clubs that then fought for equal

access to baseball grounds and the opportunity to compete at baseball’s highest levels. There

is no evidence of black ballplayers clamoring to join white baseball clubs” (11). Their own

teams and their own leagues represented a fighting chance at equality in comparison to the

White teams; more simply, if they could compete without assimilating into dominant White

culture, their racial identities could be validated and accepted.

In 1987, The Society of Baseball Research recognized Bud Fowler as the “first

professional African-American baseball player” for his participation on a white team in 1872,

however, prior to his breaking of organized baseball’s color line, he played alongside Charles

Douglass on the Mutual Base Ball Club in 1869 (McKenna, “Bud Fowler”). It was there that

desegregationist ideologies inspired color-line breakers; Fowler’s 1872 joining of an all-

white professional team in New Castle, Pennsylvania was the first of a long line of black

incursions into organized “white” baseball, such as the Independent League—baseball’s

oldest continually operating circuit (White). During his journeyman career, Bud Fowler

gradually began to compete against other talented Black players on all-white teams and his

friendly rivalry with Frank Grant is most notable; according to The Society of Baseball

7

Research, ‘Grant is arguably the best Negro player in the 19th century’ (McKenna, “Frank

Grant”). Frank Grant’s success consequently earned him the record for playing three

continuous years (1886-1888) with an all-white minor league team, a testament that largely

defies racial discrimination in the nineteenth-century context. The career of Moses Fleetwood

Walker is also most crucial to include, as his inclusion on the 1884 Toledo Blue Stockings is

historically acknowledged as the first time a Black athlete played professionally in the then-

recognized Major Leagues. Rhoden explains that Walker’s professional debut did not spur a

rush to sign further African Americans to major-league teams. Additionally, during Walker’s

time with Toledo, he faced harsh racial discrimination—yet still was allowed to play. Walker

was the catcher for the White pitcher Tony Mullane, “who conceded that he did not like

blacks, but admitted that he respected Walker’s ability and said Walker was the best catcher

he had ever worked with” (Rhoden 80-1). In a newspaper clipping from December 18, 1886,

The Sporting News remarked:

“The Newark club will probably place a novelty in the field next season in the shape

of a colored ‘battery.’ Stovey, the pitcher, and Walker, the catcher, are both colored

men. Stovey played with the Jersey City club last season and showed he was a great

pitcher. Several of the League contemplated signing him last season, but the prejudice

against his color prevented. Had he not been of African descent he would have

pitched for the New York club last fall” (The Sporting News 2).

The following season, the Newark Little Giants did indeed field both Stovey and Walker,

forming the first all-Black battery in organized baseball in the year 1887 (Riley). In that same

season, during a July 1887 game between the Newark Little Giants and the Chicago, that a

color line was established, although it was rarely acknowledged and was most often

characterized as a “gentleman’s agreement” rather than strict policy. As per a Newark

Evening News report, “Manager Charles Hackett (of Newark) received a telegram from

Captain Cap Anson (of Chicago) saying that the Chicago Club would not play if Stovey and

Walker, the colored men, were put at the points… The International League representatives

held a meeting at the Genesee House, in Buffalo, yesterday and passed a resolution

instructing Secretary (C.D.) White not to approve the contract of any more colored players.

Jersey City and some of the other clubs insisted the African players drove white men from

the league” (Mancuso). Just a month prior, a June 1887 “revolt” between Bud Fowler and

8

fellow Black player William Renfro resulted in a petition signed by nine white teammates

demanding that the integrated black players be released or ‘voluntarily’ quit (Mancuso).

Through these events in 1887, the color line in Major League Baseball was officially put in

effect.

The impact of racial discrimination in baseball was further compounded with the

1896 U.S. Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Ferguson, ultimately deciding that racial

segregation was permitted by the Constitution if the facilities for each race were equal in

quality. The establishment and legitimization of Jim Crow swiftly crossed the nation, as

facilities and services were erected for members of non-white races, but they were hardly

equal in quality or upkeep— if they were constructed at all. This de jure enforcement of

racial segregation in the South, and de facto enforcement elsewhere, further entrenched

White athletes, front offices, and owners as the controlling ethnic group and epistemological

value system in Major League Baseball. By 1900, four years after the landmark decision,

there were no Black ballplayers in the professional league (“The History of Baseball…”). As

the Black identity was increasingly and intensely marginalized, movements for equal societal

status were concurrently revitalized; activists such as Mary White Ovington, Ida B. Wells,

and W. E. B. Du Bois founded The National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People (NAACP) on February 12, 1909 (“Our History”). Civil rights ideas such as “double-

consciousness” (1903), as W. E. B. Du Bois first published, described the psychological

ordeal of perceiving one’s Black identity through the lens of a racist society: “measuring

one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity” (Hinchey). Du

Bois, in his book, The Souls of Black Folk, describes this identity as the feeling of “his two-

ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two

warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn

asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife – this longing to attain

self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging

he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost… He simply wishes to make it possible for a

man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows,

without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face” (Hinchey).

In analyzing one’s Black identity in relation to the hegemonically white society, Du

Bois sets foundational concepts in decolonial and critical race theories that—106 years

9

later—give birth to Walter Mignolo’s 2009 actionable idea of epistemic disobedience. Du

Bois’s idea of “double-consciousness” identifies the perceived inferiority of the Black

identity, and in Mignolo’s 2009 article, he adds that ‘in the 16

th

century, as Christianity came

to be the leading epistemic force in the classification of people and places, slavery became

indistinguishable from blackness’ (175). Mignolo continues, stating that “From then on, it

was a particular framing of social and psychological dimensions where ‘the lived experience’

of the Negro would always be formed by the gaze of the white” (175). Mignolo argues that

epistemic disobedience is needed to reject one’s perceived “two-ness,” or more broadly, the

gaze (and centrality) of Whiteness, in order to support and advance non-White knowledge,

values, and lived experiences (161). Through the decolonial process of de-linking

Eurocentricity and separation from White epistemology, Black individuals can reject White

rules—such as their unofficially enforced color lines. In applying these concepts to Major

League Baseball, it can be argued that its color line has reinforced “epistemic privilege[s] of

the First World” and racial opinions in America (166). Currently, even though it is portrayed

as long-gone, Major League Baseball still contains artifacts from its racist past because of its

subconscious or subvert systemic racial discriminations. These artifacts are still felt among

non-white players, forcing many Black or Latin athletes to reconcile their racial identities

much as Du Bois did—wishing their “double selves” could be accepted as equal.

Prior to World War I and the formation of the Negro Leagues in 1920, the Cuban

Giants established themselves as the original model for Negro League teams as a result of

their sustained success beginning in 1885. They were the first African American team to

fully compensate their players, but ironically, none of the players were actually of Cuban

nationality (Burgos Jr., “Economics” 47). As noted in Bill Kirwin’s 2005 book, Out of the

Shadows: African American Baseball from the Cuban Giants to Jackie Robinson, it is

suspected that their name intended to ‘avoid the opprobrium of hostile white Americans by

“passing” as Cubans even though their ruse hardly deceived informed baseball fans, who

already were accustomed to such euphemisms as “Cuban,” “Spanish,” and even “Arabian”

being applied to black ballplayers by the sporting press’ (Kirwin). Their success was soon

emulated by other Black baseball clubs, one such being the Page Fence Giants from 1885 to

1898. First created by white businessmen as a way to advertise their fencing company, the

Page Fence Giants competed against white teams in the Michigan State League (MSL) and

10

barnstormed—to travel rapidly around rural areas, staging exhibition matches as part of a

campaign—the nation seeking competition from the likes of Honus Wagner’s Adrian

Demons/Reformers, Frank Grant’s Cuban X-Giants (a branched team from the

aforementioned Cuban Giants, “X-Giants'' referring to being “Ex-Giants”), and Frank

Dwyer’s all-white Cincinnati Reds (Baseball Reference). All while the U.S. Supreme Court

decided to uphold and permit racial segregation, Black baseball was thriving. In 1896, the

Page Fence Giants competed predominantly against the Cuban X-Giants, ultimately winning

their match-up and claiming the title as the best team in Black baseball (Baseball Reference).

Charlie Grant, a former member of the Page Fence Giants, came extremely close to breaking

Major League Baseball’s newly formed color line when he was recruited in 1901 by

Baltimore Orioles manager John McGraw to play in the Major Leagues (“Charlie Grant”).

Grant was renamed “Tokohama,” identifying as Cherokee Indian, in order to pass through

the color line—but unfortunately, his true identity was revealed before playing in a major

league game (McKenna, “Charlie Grant”). In response to McGraw’s ploy, Chicago White

Sox owner, Charles Comiskey, stated: “I'm not going to stand for McGraw ringing in an

Indian on the Baltimore team. If Muggsy really keeps this Indian, I will get a Chinaman of

my acquaintance and put him on third. Somebody told me that the Cherokee of McGraw's is

really Grant, the crack Negro second baseman from Cincinnati, fixed up with war paint and a

bunch of feathers” (Loew). Used as a strategy to advance into predominantly White systems,

Grant’s attempt at “passing” was quickly muted due his popularity as a Negro League player.

In less than fifteen years of its recognized existence, the color line was already under

challenge by a Black player and a white facilitator; a practice that would be replicated by

Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson less than forty-five years later. This “passing” strategy is

used by people of color or members of multiracial groups in order to be perceived as White

in order to escape oppressive conventions or discriminatory systems. “Passing” has a long

history in America, dating back to the Antebellum period when passing as White was a

gateway to freedom (Hobbs). Black pioneers like Charlie Grant, Moses Fleetwood Walker,

and Bud Fowler made substantial forward progress towards integration—and upon Fowler’s

death in 1913, passed the pioneering torch to former Cuban X-Giant Rube Foster.

Less than two years after the conclusion of World War I, Rube Foster and his fellow

Black team owners mutually agreed that stability was needed for the continued success of

11

organized Black baseball, thus creating the Negro National League in February 1920. The

official formation of the league provided unified financial and competitive security for all the

involved teams. This agreement also tried to prevent the financial folding of many Black-

owned teams and leagues that had been created prior. Rube Foster opined his frustrations

about the health of Black baseball in the Chicago Tribune between late 1919 and early 1920,

pitching the promotion and organization of Negro Leagues to eventually play white

ballclubs: “Each club will be allowed to retain their players, but cement a partnership in

working for the organized good for baseball… This will pave the way for such champion

team eventually to play the winner among whites. This is more than possible. Only in

uniform strength is there permanent success” (Francis). A 1921 Afro-American column

summarizes Foster’s articles, repeating his pleads for African American investment: “Here is

a chance for the businessmen of Baltimore to get busy and see that this city gets a league club

so that it will be possible to see the big colored teams in action here. There is money in

baseball and we can’t see to save our life why some of our colored businessmen of this city

don’t get into the game and reap some of it” (“Rube Foster Speaks Out”). Rube Foster

ultimately desired to “keep Colored baseball from the control of whites” by “[creating] a

profession that would equal the earning capacity of any other profession” (Kelly). By doing

so, Foster wanted to substantially “do something concrete for the loyalty of the Race”

(Kelly). In the first year of Foster’s Negro National League, an October 8, 1920, edition of

the Baltimore Afro-American prefaces an upcoming game between the St. Louis Giants, “this

city’s best colored team,” and the White team in the National League, the St. Louis Cardinals

(“Plays National League Team”). While seeming like an inconsequential local exhibition at

first, this game marks an early 1900s instance in which White teams agreed to play Black

teams. Rube Foster’s written petitions and creation of the organized league was making

significant progress towards integration, and games between Black and White teams began to

gradually become more frequent. Through the Negro National League’s determination, the

teams embodied a confident investment in themselves and their own Black identity—

separate from White interference—and reflected philosophies of self-improvement and

unified prosperity presented by Booker T. Washington in the late 1800s.

As Negro National League stars like Oscar Charleston and Cool Papa Bell paved the

way for more, the legacies of many Negro League players would be incomplete without

12

crediting the principal owner of the Homestead Grays, Cumberland Posey Jr. The only

person in both the Baseball and Basketball Hall of Fame, Cum Posey was also able to “pass”

as White in certain scenarios due to his light-skinned African American race (McKenna,

“Cum Posey”). While this physical quality had its advantages, he still had to tolerate racial

discrimination including segregation in organized basketball, thus forcing Posey to play

basketball under the name “Charles Cumbert” in order to pass as White. In 1911, he signed a

contract to play for the Homestead Grays but by 1920, Posey began a different business

endeavor: purchasing the majority ownership stake in the Homestead Grays, making him the

principal owner (“Cumberland Posey”). Under Posey’s stead, the Homestead Grays became a

powerhouse Negro League team—until 1922, when greater competition created greater

demand. Successful businessman and illegal gambler, Gus Greenlee, formed a competing

team in the Pittsburgh Crawdads in 1922 and consequently threatened the Grays baseball

dominance. Their lively competition, regional popularities, and strong baseball identities kept

them both in successful operation during the Great Depression, even so that Hall of Fame

members Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, and Cool Papa Bell played for both teams during

their illustrious careers. In a 2016 Andscape article, Nancy Boxill disclosed that her

grandfather, Cum Posey, had discussed with Branch Rickey pathways of integrating Major

League Baseball, but Posey untimely passed away in 1946 before seeing his last dream come

to life (Washington).

13

Figure 1. Image displaying a fallen soldier juxtaposed with a

Black pitcher.

While it is historically accurate that Cum Posey, Rube Foster, Gus Greenlee, and their

contemporaries were not, by definition, color line breakers, their influence on the growth and

popularity of the Negro Leagues were integral to its later success after World War II. But

even as African American soldiers, and Negro League players alike, returned home after

fighting for their country, the color line waited them. Presented in a pamphlet cover sourced

14

online from the National Negro Congress Records, an African American pitcher is

juxtaposed with a dead soldier; visually depicting the Black identity’s frustrations regarding

their persisting status as second-class citizens. Inserted below as Figure 1, this imagery was

created by Benjamin J. Davis Jr. in his campaign for New York City Council in 1945 (“A

Black Candidate Runs…”). His membership in the “End Jim Crow in Baseball” committee

also spelled support for the Communist Party as well as the New York Trade Union Athletic

Association (TUAA) (Nathanson). Their post-war protests for desegregated baseball

demonstrates the clear connection between African American civil rights activism and its

constant intertwined history with baseball. Overseas, Negro League athletes played

recreational baseball alongside Whites—very similar to the part-time integration that

occurred during the Civil War. Additionally, because of the depleted talent pool in the United

States during World War II, many historians argue that it could have been an ideal

opportunity to integrate Major League Baseball—but alas, MLB decided against it. In a

November 1945 edition of The Sporting News published after the end of WWII, a column

details the findings of a probe of race-based discrimination in organized (White) baseball.

The article states that “Negroes are not in the major leagues and that they should be; that

there is prejudice.” While the probe clearly acknowledges the existence of a color line, the

investigation also concludes that the contractual arrangements between the Negro League

organizations and its players are “loose,” and thus “before anything can be done for Negro

baseball insofar as an invasion of white Organized baseball is concerned, the Negro leagues

must institute a cleanup.” According to Leslie Heaphy’s article published within the book

Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II, MLB resisted integrating high-quality

Black players and “instead they turned to men such as Pete Gray, the one-armed outfielder,

and over 400 other men, none of whom were African American. The excuse given almost

universally was that the players did not have the skills; this was quickly disproved when

Jackie Robinson went on to be named Rookie of the Year when he was first given the

opportunity in 1947.” One of the largest obstacles for integration was then-MLB

Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis; his iron-fisted upholding of the color line and

perpetuation of racial prejudice prevented teams and front offices from attempting integration

(Burgos Jr. 87). At this point during the early 1900s, racist beliefs towards African

Americans were hegemonically-held—this contextual detail is articulated in a 2004 ESPN

15

article: “Landis has been blamed for delaying the integration of the major leagues, but the

truth is that the owners didn't want black players in the majors any more than Landis did”

(Neyer). Landis’s reign as MLB Commissioner came to an unceremonious end when he died

in November 1944, and nine months later, Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to a minor

league contract. In doing so, it was only a matter of time until segregated baseball became a

relic of the past.

In acknowledging these Black baseballers and their significance to American

baseball, it is imperative to also acknowledge the price they paid for pioneering pathways

towards equality. Octavius Catto, one of the founding members of the Philadelphia Pythian

Base Ball Club in 1865, was entrenched in civil rights activism in addition to his baseball

interests. He was an educator and an intellectual, striving for racial equality. Catto helped

form the “National Equal Rights League, the first U.S. group devoted to promoting black

equality” in 1864, as well as “work[ing] zealously alongside Frederick Douglass and other

abolitionists to pass the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery” (Elias). Catto also played a

hand in the successful passing of the 14

th

and 15

th

amendments, respectively, becoming “one

of the most influential African American leaders in Philadelphia during the 19th century”

(“A Quest for Parity”). However, on October 10, 1879, Catto was shot and killed in cold

blood; “a martyr to racism” on the first day African Americans were permitted to vote

(Elias). Charles Douglass, a contemporary of Catto, had a largely successful career in politics

and as a member of the NAACP. His father’s popularity and influence assisted his career,

resulting in a relatively large number of opportunities compared to most black men at the

time (Swanson 12). Bud Fowler, on the other hand, did not have the privilege of nepotism

and in 1913, died at age 55 with little publicly known about him.

During World War II, when Major League Baseball was actively refusing integration

by instead playing the one-armed outfielder Pete Gray and three-and-a-half-foot-tall Eddie

Gaedel, then-Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley created a professional women’s

baseball league to keep ballparks busy (Francis). Beginning in 1943, the All-American Girls

Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) gave over “500 women an opportunity that had

never existed before” (Francis). These women, on one hand and much like Rosie the Riveter

icon, benefitted from eroding social norms during wartime. But on the other, Zirin documents

that ‘the women who participated in the league were all-white and had to attend charm

16

school in order to maintain images of femineity’ (95). They were the “All American Girls,”

but African American women were nowhere to be seen. Mami “Peanut” Johnson, formerly of

the Negro Leagues, tried out for the AAGPBL in 1951, but was not selected due to her race

(“Mamie Johnson”). Johnson, a Black woman, was not permitted to play in the women’s

league, yet was allowed to play in the barnstorming Black one. One of the reasons for this

was because the AAGPBL was managed by MLB-affiliated men such as Branch Rickey,

several coaches from the Chicago Cubs, and Max Carey, among others. It became abundantly

clear in their hurried inception and backing from MLB that they were preferred option of

entertainment over the previously established Negro Leagues.

Despite this step backward, Black athletes finally prevailed when Jackie Robinson

breached Major League Baseball’s color barrier shortly thereafter in 1947. But this sudden

influx of Black talent did not come without costs. As baseball forces Rube Foster, Josh

Gibson, and Jackie Robinson had trudged forward towards racial desegregation, their place in

integration resulted in anticlimactic, and fatal, consequences—a price to be paid for

disrupting the hegemonic status-quo. Foster, the primary father of the Negro National League

in 1920, was exposed to a gas leak in 1925 which, in turn, deteriorated his mental stability;

he was admitted into a mental asylum a year later. His tragic death served as a precursor to

the downfall of the league he created, and within five years, the Negro National League was

also finished (Odzer). Josh Gibson, a prolific Negro League athlete, was long assumed to be

the first Black player to break Major League Baseball’s color line in the twentieth century

until his untimely death at the age of 35. Gibson’s athletic prowess overshadowed his

consistent substance abuse and major health problems, ultimately paying the ultimate price

(Hamill). It’s fair to imagine how Gibson’s career would have transpired if he played in

integrated Major League Baseball, but regardless, his baseball achievements continued to

pave the way for the athletic validation and racial acceptance of Negro League athletes.

Finally, its well-known in many scholarly circles that Jackie Robinson had an active political

career after his baseball retirement. In some circles, he was called “the White man’s Negro”

due to his precarious acceptance in White society. However, he was actively involved with

the NCAAP and maintained a close professional relationship with Martin Luther King Jr.,

and his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (“Robinson’s Later

Career”). In the 2014 volume of critical essays Sports and Identity: New Agendas in

17

Communication, Abraham Khan articulates that “In contemporary culture, Jackie Robinson

stands as an irrefutable figure of civic courage and embodiment of social progress…Be that

as it may, the HUAC testimony, his endorsement of Nixon in 1960, his active campaigning

for Rockefeller, and his support for US involvement in the Vietnam War mitigate awkwardly

in black history against both his status as an integration pioneer and the luminous mythos that

surrounds the remarkable events of his life” (Brummett). He critiqued the NAACP in 1967,

“I am forced to say that I am terribly disappointed in the NAACP and deeply concerned

about its future,” in an attempt to “reinvigorate its original mission, not an attempt to

undermine its founding goals” (Brummett). Khan argues that Robinson, in his post-playing

career, was liberal in the way he addressed desegregation but was a civic republican in his

statements regarding black politics (Brummett). Through his essay, it is evident that

Robinson’s duality of political rhetoric adds another layer of depth to his well-documented

legacy. On October 24, 1972, Jackie Robinson passed away at the age of fifty-three via a

heart attack; his early death and health issues capitalizing the steep price he paid for racial

desegregation in Major League Baseball.

III. LATINOS & PASSING: A TRACING OF EARLY PUBLIC

RECEPTION

Throughout his 2007 book, Adrian Burgos Jr. details the advancement of Latinos in

Major League Baseball—and the different prejudices, experiences, and careers Latinos have

experienced compared to their African American counterparts. Burgos Jr. also analyzes that

Major League Baseball’s color line has treated Latinos differently, which supports my

inclusion of his work in this historiography at this particular location. Before advancing into

the subsequent downfall of the Negro Leagues as a result of integration, it is important to

acknowledge and trace the existence of Latino athletes in Major League Baseball, as their

different ethnic qualities presented different race-based privileges. They were present and

influential in Major League Baseball before, during, and after the breaking of the color

barrier in 1947. In fact, Burgos Jr. explains that Jackie Robinson was not Branch Rickey’s

first choice to integrate Major League Baseball, but rather it was the Afro-Cuban athlete

Silvio García instead (186). Many historians have explored why García was never signed; he

was, as Branch Rickey identified in 1943, a “major-league talent” (186). Burgos Jr. notes that

18

there were multiple reasons García was not chosen, such as his temperament or advanced

age, but the foremost reason stemmed from his Latino ethnicity: “Importantly, signing a

darker-skinned Latino like García would not have obliterated the racial ideas that had

sustained the most persistent function of baseball’s color line—exclusion of African

Americans (Burgos Jr. 186). The reason being for this critical ethnic difference is because

there were already Latinos and Afro-Latinos present in Major League Baseball before Silvio

García’s potential entrance—his barrier-breaking signing would not, in actuality, have

broken anything at all. The purpose of this section will intend to acknowledge those Latinos

already present in MLB during the Negro League era.

In Chapter One of Adrian Burgos Jr.’s 2007 book, he highlights the first Cuban player

in professional baseball: Esteban Bellán (17). His debut in 1868 contained little fanfare, as

American professional baseball organizations had yet to take concrete shape and player

movement between newly formed (and quickly folding) regional teams and leagues were

frequent (21). Burgos Jr. contextualizes that Cuba’s geographical proximity to the United

States was not the only contribution to assimilation, as Cuba’s Ten Years War (1868-78)

resulted in emigration that consequently “worked to facilitate baseball’s assimilation into

Cuban national culture as part of a broader shift in the cultural orientation an attitudes of

Cuban elite” (19). During this time, Cuban émigrés moved to the United States for improved

sociopolitical or economic opportunities, including the “father” of Cuban baseball, Nemesio

Guillo, and the future founders of the Almendares Baseball Club, Carlos and Teodoro Zaldo

(Echevarría). Over the next thirty years, according to Roberto González Echevarría’s 2009

Encyclopedia Britannica article, players like Luis Bustamante, Cristóbal Torriente, and Lou

Castro earned great success—the latter of which became the second Latin American in the

recognized major leagues. Concluding the Spanish-American War and the political unrest

following Tomás Estrada Palma’s 1906 resignation, United States military forces occupied

Cuba—and in turn, baseball’s influence followed suit once again (Echevarría). In his article,

Echevarría elaborates:

“During the three-year occupation, the presence of baseball on the island increased.

Negro-circuit and major league teams played often in Cuba. The Cincinnati Reds

visited in the fall of 1908 and were shut out three times by Almendares pitcher José

de la Caridad Méndez. Because Méndez was black, he was unable to play on a major

19

league team; he had a notable career as a player and later as manager of the Kansas

City Monarchs, one of the best teams in the Negro leagues. When white Cubans

Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsans joined the National League Cincinnati Reds in

1911, they became the first significant major league Latin American players in the

20th century” (Echevarría).

Echevarría’s article in Encyclopedia Britannica converses with Adrian Burgos Jr.’s book by

detailing that because of wars, political unrest, and military occupation, American and Cuban

people exchanged cultural capital—including baseball. In the quote above, Echevarría

indicates that José de la Caridad Méndez was prevented to play in Major League Baseball

because of its color line, despite his extraordinary talent. Burgos Jr. provides further

historical context, drawing upon Bill Phelon’s 1912 article in Baseball Magazine: “most

[Cuban ballplayers] are black, jet black, and their star battery performers are all African of

the darkest shade” (Burgos Jr. 99). Black Cubans such as José Méndez, Cristobal Torriente,

and Gervasio “Strike” Gonzalez may have been ‘A1 performers,’ but because they were so

visibly black, their prominence in Cuba’s professional ranks, some contended, ‘block[ed] the

path of Cuban teams to full recognition and proper welcome in the States’” (99). Cuban

players like Esteban Bellán and Luis Castro were able to “pass” enough to be accepted into

American professional baseball leagues, but players like Jose Mendez and Cristobal

Torriente were not due to the color of their skin. It was clear that light-skinned Latino players

were welcome to cross baseball’s color line, but darker-skinned Black players were not.

According to a 2008 Harvard publication by Jennifer L. Hochschild, “During the nineteenth

century, the Census Office did not consider the people we now call Latinos or Hispanics to

be formally distinct from whites” In the case of American baseball, “passing” was indeed

limited to Latinos of light-skinned phenotype in order to obtain the ‘freedom’ to play in the

Major Leagues. This historical record largely clarifies how light-skinned Cuban baseball

players were able to break into professional baseball, and why their darker-skinned

counterparts were left to play in the Cuban professional leagues or the Negro Leagues until

Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso’s Major League Debut in April 1949 (Baseball Reference).

20

I V. AFRO-LATINOS & RISING LATINO PROMINENCE IN

MLB

In the previous section, I mentioned that Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso was historically

not the first Afro-Latino in Major League Baseball, despite being widely acknowledged as

the first. Light-skinned Cubans and were able to “pass” and outwardly identify as Latino,

whereas darker-skinned Latinos were left out because of their phenotype. In his book, Adrian

Burgos Jr. cites an October 1913 Amsterdam News article containing a quote from then-New

York Giants manager John McGraw, stating if “[José Méndez] was a white man he

[McGraw] would pay $50,000 for his release from Almendares” (106). As a result of his

exclusion, Méndez finished his acclaimed career with the Kansas City Monarchs in the

Negro National League (Baseball Reference). About fifteen years after Méndez’s retirement,

the New York Cubans—led by the legacy of Martín Dihigo—became the dominant team in

the Negro National League by winning the Negro League World Series in 1947. Members of

the team included thirty-three-year-old Silvio García (the player Branch Rickey favorably

scouted to break the color line), forty-year-old Luis Tiant, and twenty-one-year-old Orestes

“Minnie” Miñoso. Their 1947 championship was the penultimate Negro League World

Series ever played, as Jackie Robinson’s debut in the same year signaled the end of Negro

League competitive prosperity.

Larry Doby was second to integrate—and first to sign and play directly for a Major

League club—with the Cleveland Indians in 1947, and the seventh barrier-breaking player,

Satchel Paige, was not too far behind debuting on July 9, 1948, also for the Cleveland

Indians. Between them were sequential debuts of Hank Thompson (July 17), Willard Brown

(July 19), Dan Bankhead (August 26), and Roy Campenella (April 20), but the individual I

will primarily provide historical context for is the eighth overall and third for the Cleveland

Indians: Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso (Baseball Reference). As articulated by Adrian Burgos Jr.,

“Miñoso and [Vic] Power and the black Latinos who followed them broke into organized

baseball not only as black men but also as Latinos, requiring cultural adjustments that further

complicated their place in this integration generation” (Burgos Jr. 181). Despite Miñoso

debuting for the Cleveland Indians on April 19, 1949, he was quickly traded to the Chicago

White Sox, becoming the first Black player in the history of their franchise on May 1, 1951.

Burgos Jr. details Miñoso’s “double impact of race and ethnicity” here: “The manner in

21

which Miñoso responded to social conditions challenged the popular stereotype of the ‘hot-

blooded Latin.’ The English-language press often poked fun at Miñoso accent. On the

diamond he dealt with beanballs, bench jockeying from opposing teams, and jeers from fans

who remained opposed to integration… Miñoso’s example of fighting back without anger

made it easier for Latinos to later speak out against those who denigrated their place in U.S.

society” (Burgos Jr. 194-5). Although neither the first Black nor Cuban player, Orestes

“Minnie” Miñoso was the Jackie Robinson for darker-skinned Latinos; cementing his

foundational impact for all Afro-Latino players that followed, including Roberto Clemente,

Juan Marichal, Felipe Alou, and Orlando Cepeda as well as more contemporary players such

as Sammy Sosa, Carlos Delgado, David Ortiz, and Manny Ramirez.

Before debuting with the Pittsburgh Pirates on April 1, 1955, Roberto Clemente was a

minor-leaguer for the Brooklyn Dodgers. According to a 2005 ESPN article, the Dodgers

wanted more than just Clemente’s talent; they wanted to keep him away from joining the

then-New York Giants and Willie Mays. Stew Thornley, in his 2006 article in SABR’s The

National Pastime publication, analyzes a questionable theory that Clemente’s demotion to

the minor leagues was intended to hide his extraordinary talent from other baseball clubs, and

also explores the existence of an unofficial “race quota” on the Brooklyn Dodgers. In 2005,

at the age of 90, Emil Bavasi (the former vice president of the Dodgers) stated in an

interview with Thornley that Clemente’s promotion would have demoted George Shuba—a

popular teammate in the Dodgers clubhouse. In the interview, Bavasi recalls a conversation

with Jackie Robinson regarding the potential transaction: “With that [Robinson] shocked me

by saying, and I quote: ‘If I were the GM [general manager], I would not bring Clemente to

the club and send Shuba or any other white player down. If I did this, I would be setting our

program back five years.’” This set-back, as Robinson suggests, was “the thought [that] too

many minorities might be a problem with the white players” (Thornley). In his article,

Thornley states that claims like these are difficult to definitively prove, but despite its

ambiguity, enough contextual circumstances point to an coincidental demotion to the Minor

Leagues. As a result, Clemente’s season-long demotion—and obvious baseball talent—

resulted in his first overall selection in the 1954 Rule 5 Draft by Branch Rickey’s Pittsburgh

Pirates. In the November 23, 1954, edition of the Pittsburgh Press, Clemente was described

as an alarming first round selection: “Brach Rickey was a real bargain hunter and paid only

22

$4000 for the highly touted “sleeper.” Branch Rickey Jr., representing his father, caused a

gasp of surprise when he named Clemente as the draft’s first choice. The Puerto Rican Negro

batted only .257 in 86 games at Montreal last season, where he was used chiefly for

defensive purposes” (“Bucs Wide Awake”).

Figure 2. Roberto Clemente, 1970.

In addition to being subject to a manipulative demotion, Roberto Clemente also

experienced racial whitewashing that centralized Whiteness in an attempt to “mute cultural

23

difference and to project an image of assimilated Latinos to the baseball public” (Burgos Jr.

223). As Burgos Jr. has documented, Clemente was periodically referred to as “Bob” by

American sportswriters. By the early 1960s, however, sportswriters had dramatically upped

the usage and newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette had followed suit to

Americanize his identity (Jordan). This would continue for nearly a decade, as a fellow

Pennsylvanian newspaper, The Evening Sun, also touted his extraordinary talent whilst, too,

projecting a White perspective of him—demonstrated in Figure 2 to the left (Eck). In his

book, Adrian Burgos Jr. furthers examines Clemente’s racial discrimination, particularly

Clemente’s experiences of racialization and intellectual disenfranchisement by sportswriters.

Burgos Jr. draws on Samuel O. Regalado’s 1998 book, Viva Baseball! Latin Major Leaguers

and Their Special Hunger to document Clemente’s quotes in broken English that

purposefully emphasized his ethnicity: “I no play so gut yet. Me like hot weather, veree hot. I

no run so fast in cold weather” (Burgos Jr. 225). Also referred to as the “flashing Latin” or

the “chocolate-covered islander,” Clemente confronted this unfair racialization, saying “I

never talk like that; they just want to sell newspapers” (Burgos Jr. 225). Burgos Jr., in the

entirety of his book, compiles and establishes examples of clear and present racial

discrimination in Major League Baseball after racial integration in 1947—and similarities

can be drawn between Clemente’s racialized treatment by sportswriters and Sammy Sosa’s,

nearly sixty years later. In reporting coverage of Sosa’s 2003 corked bat incident, Adrian

Burgos Jr. states that “Sosa’s quote portrayed him as less intelligent than his peers and

unintelligible to readers” (Burgos Jr. 253). Burgos Jr. continues, explaining that “Latino

journalists at the 2003 National Hispanic Journalists Conference decried the manner in which

verbatim quotes of Latino players affect popular perceptions, leading many to see Latinos as

unintelligent regardless of their individual speaking ability” (Burgos Jr. 254).

V. CONSEQUENCES OF INTEGRATION

In August Wilson’s 1985 play Fences, which explores the covert consequences of

America’s color line in the mid 1950’s, Troy Maxson, the father, and main character of the

play, was shut out of a baseball career due to his race, thus leaving him with deep feelings of

anger towards racial discrimination. His suppressed resentment toward his own lack of

further opportunity—and financial prosperity—fractures his family, which he only

24

compounds when, as a result of his own experiences, he prevents his son Cory from playing

college football. Troy’s embittered experiences with racial discrimination cause a wedge

between him and his son, as their rocky dynamic is one of the main cores of August Wilson’s

play. In one scene, Troy exclaims his frustration with the timing of major league baseball

integration and Jackie Robinson:

ROSE. They got lots of colored boys playing ball now. Baseball and football.

BONO. You right about that, Rose. Times have changed, Troy. You just come along

too early.

TROY. There ought not never have been no time called too early! Now you take that

fellow . . . what's that fellow they had playing right field for the Yankees back

then? You know who I'm talking about, Bono. Used to play right field for the

Yankees.

ROSE. Selkirk?

TROY. Selkirk! That's it! Man batting .269, understand? .269. What kind of sense

that make? I was hitting .432 with thirty-seven home runs! Man batting .269 and

playing right field for the Yankees! I saw Josh Gibson's daughter yesterday. She

walking around with raggedy shoes on her feet. Now I bet you Selkirk's daughter

ain't walking around with raggedy shoes on her feet! I bet you that!

ROSE. They got a lot of colored baseball players now. Jackie Robinson was the first.

Folks had to wait for Jackie Robinson.

TROY. I done seen a hundred niggers play baseball better than Jackie Robinson. Hell,

I know some teams Jackie Robinson couldn't even make! What you talking about

Jackie Robinson. Jackie Robinson wasn't nobody. I'm talking about if you could

play ball then they ought to have let you play. Don't care what color you were.

Come telling me I come along too early. If you could play . . . then they ought to

have let you play. (Wilson 1.1)

Another typical reaction to the same situation can be seen in the responses of Buck O’Neil,

as recorded in Joe Posnanski 2007 book, The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck

O'Neil's America. O’Neil, the first Black coach in the Major Leagues, holds much less

animosity towards baseball’s segregation and, because of his career on-and-off the field, and

was recently elected to Major League Baseball’s Hall of Fame as part of the 2022 class. In

25

1955, Coach O’Neil helped the Chicago Cubs identify talent from predominantly black high

schools and colleges (Muskat). However, O’Neil also recalls ‘what the Negro Leagues were

really like,’ stating that “we had become conditioned to racism,” when recalling a half-

baseball, half-show organization he played for in the 1930’s (Posnanski 23). He continues,

“Hatred will steal your heart, man. You don’t have any fight left in you. You accept what’s

around you. That’s what this country was like. We thought it would change someday. We

just waited for it to change” (Posnanski 22). O’Neil reminisces upon the era of the Negro

Leagues like August Wilson’s character, Troy Maxson, but their attitudes towards racial

segregation are decisively opposite. O’Neil converses with Monte Irvin about timing, a

foundational theme in Fences: “[Irvin] said that had he been born a little later, he would have

spent his whole career in the Major Leagues, and people might think of him as one of the

greatest players who ever lived. They might think of him the way they think of Willie Mays,

Joe DiMaggio, and Mickey Mantle. Then again, [Irvin] said, had he been born a few years

earlier, he might not have been known at all. He would have spent all his life in the Negro

Leagues, playing baseball on rock diamonds in small towns. The only way anyone would

know him would be through whispers and myth. ‘Either way, though, I would have gotten to

play ball, and that’s all I ever wanted to do,’ [Irvin] said. ‘I don’t feel sorry for myself. I got

to play’ (Posnanski 222). The two opposite attitudes of Maxson and O’Neil (and Irvin)

summarize how African Americans generally felt about the color line in Major League

Baseball; either they were proud to have simply played, or on the contrary, they felt unfairly

robbed of further opportunities. As demonstrated by Rob Ruck and Buck O’Neil, Major

League Baseball’s segregated status meant a well-represented league for African Americans

where they could communally participate in an entity that was not dictated by Whites.

However, as shown in August Wilson’s Fences, frustrations regarding the unilateral unequal

opportunities were also prevalent. Even though integration represented progress, the Negro

Leagues and other Black-owned institutions rapidly collapsed after Jackie Robinson’s

barrier-breaking debut in 1947.

Historians have also had differing takes on the effects of baseball’s desegregation.

William C. Rhoden, in his 2006 book Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and

Redemption of the Black Athlete, describes the collapse of the Negro Leagues after

integration. “Just one year later,” Rhoden writes, “in 1948, the black leagues were in

26

shambles. Many of the Negro League owners, so engrossed in the period of prosperity, never

saw what hit them until it was too late. Effa Manley, the co-owner of the Newhark Eagles,

said, ‘Our troubles started after Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers.’ Manley, who was

white but often passed for a fair-skinned African American, said ‘[Black fans] are stupid and

gullible in believing that [Branch] Rickey has any interest in Negro players other than the

clicking of his turnstiles’” (Rhoden 119-20). Rhoden continues, establishing that Manley was

naïve in believing that integration would help the Negro Leagues; instead of energizing and

popularizing the league in which Robinson, Campanella, Irvin—and so many others

originated from—the Negro Leagues devolved into a glorified minor-league system in which

its premier talent could be poached with relative ease. Sports Historian Dave Zirin adds:

“Manley described ‘being squeezed between intransigent racial considerations on one hand

and cold business reasoning on the other’” (Zirin 106). Zirin states that MLB general

managers like Branch Rickey and Bill Veeck ‘raided Negro League talent seemingly

overnight,’ as a part of their claims that ‘There are no Negro Leagues as such as far as I’m

concerned,’ and insisting that ‘Negro Leagues are not leagues and have no right to expect

organized baseball to respect them’” (Zirin 105). And it wasn’t only the Negro League teams

that folded; as Rob Ruck describes, “so did the institutions it had protected. Black hospitals,

newspapers, banks, insurance companies, hotels, and restaurants were often decimated by

competition from better-funded competitors. Many folded as a result. Only eight of over one

hundred black hospitals operating in 1944 remained open fifty years later. The black press

lost most of its circulation and some of its most talented writers; black banks all but

disappeared” (Ruck 116). In examining the consequences of Robinson’s breaking of Major

League Baseball’s color line, it’s clear that the Negro Leagues consequently went into a

sharp freefall that negatively affected its non-premier players, its organizations and team

owners, and its surrounding network of Black-owned businesses and communities.

VI. CONCLUSION

As this historiography has demonstrated, racial discrimination in Major League

Baseball did not cease to exist after Jackie Robinson’s entrance in 1947, nor did his signing

with Branch Rickey indicate a new era. Prominent Black players such as Moses Fleetwood

Walker, Bud Fowler, Charlie Grant, and Cumberland Posey Jr. all individually challenged

27

variations of a color line in organized baseball and deserve to be equally recognized as

similar pioneers. Once it was ‘the right time’ for integration, however, baseball’s style of

play would be changed forever (Ruck 84). Rob Ruck, in his book, highlights the infusion of

speed and power that Black and Latin players brought to Major League Baseball. Gone was

advancing “base-to-base” and the dead ball and entering was “the consummate speed of a

quality rarely demonstrated since the Ty Cobb heyday” (105). The element of speed and style

added a larger cerebral element to America’s pastime, as different pitching, defense, and

baserunning probabilities would now occur. The ongoing clash between the hegemonically

White style of play and the Black or Latin styles of play—and the racial discrimination that

stems from these differences—will be noted further in the following chapter.

In contemporary Major League Baseball, there remain many persisting aspects of a

discriminatory color line. Since 1887, owners and organizations have collaborated to resist

Black and Latin prominence—even despite its recent advancements of official recognition

and public popularization. Much has been previously established about the collapse of the

Negro Leagues because of integration, however, as Adrian Burgos Jr. documents, Latinos

were “not at all tangential to the working of baseball’s color line;” or more simply, that they

were also subject to racial discrimination due to the color—or lightness of color—of their

skin (Burgos Jr. 12). Afro-Latinos, subjects of dual exclusions, were scrutinized due to their

presumed lack of intelligence as a result of their English language fluency (Burgos Jr. 259).

Additionally, in the 1998 home run race that ‘saved baseball,’ Sammy Sosa was framed as

the ‘happy-to-be-here’ sidekick to Mark McGuire’s archetypal American hero, reinforcing

the centricity of Whiteness as and thus, minorities such as African Americans or Latinos as

inferior (Butterworth). Eurocentricity, as evidenced by this historiography, has perpetually

been the dominant value system and cultural priority in American baseball.

Research of American baseball and the Negro Leagues has significantly brought key

pioneers like Charlie Grant and Moses Fleetwood Walker to the forefront of discussions

about of Major League Baseball’s color line. Their achievements, among others, prove that

Jackie Robinson’s barrier-breaking debut in 1947 was merely another step towards racial

acceptance that is still ongoing today. Fredrick Douglass and W. E. B. Du Bois, also,

contributed greatly to racial movements in baseball; their activism, founded on desires of

“autonomy, equality and opportunity” was mirrored on the baseball diamond and team

28

building. If a Black player could earn his place on a White, organized team, then they could

therefore do the same in civil society. However, as the twentieth century came, one had to be

perceived as White to play at the highest level—light-skinned African Americans or Latinos

could finesse, via “passing,” an entrance into professional baseball, but darker-skinned

players were shut out and forced to stay toiling in the Negro Leagues. Patty Loew, in her

2004 article, articulates MLB’s color line’s arbitrary nature to perfection: “Hispanics

presented a special challenge to racial purists, who relied more on outward appearance than

ethnic origin. Light-skinned Cubans and other Hispanics were invited to the majors, while

dark skinned Latinos were ushered to the Negro leagues, which was itself not immune to race

blurring…The ironies and inconsistencies of major league baseball's misguided race-based

policies were obvious” (Loew). This historiography acknowledges and contextualizes

nuances of organized baseball’s color line and sets an evidence-based foundation that will be

applied to a contemporary baseball context in Chapter Two.

29

CHAPTER 2

CONTEMPORARY MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL

I

NTRODUCTION

Despite Jackie Robinson blazing the trail for African Americans in baseball when he

broke the color-line in 1947, New York Times journalist Brent Staples correctly identified in

1987 that ‘baseball has the longest, most perversing history of discrimination in professional

sport’ (Ruck 190-1). After 75 years of racial integration, non-white players in Major League

Baseball today are still subject to systemic racial discrimination and pressure to play the

“white way.” This de facto rule system is largely gate-kept by white players, managers, and

front offices to maintain control of their ‘national pastime.’ However, decolonial theory

suggests that these structural and informal discriminatory systems need to be challenged to

best include, benefit, and increase the representation of Black and Latin players in Major

League Baseball. This stance purposefully rejects Eurocentricity in favor of focusing on non-

white history and culture that has been largely erased or ignored by the dominant systems of

power and influence. In this chapter, I will present evidence of contemporary socioeconomic

inequalities between White and Black or Latino players throughout their careers, starting

with the increasing price to play, develop, or practice and ending with their financial

compensation once entering professional baseball. Additionally, I will document the

prevalence of racially coded descriptors for athletes of different ethnicities and discuss how

Major League Baseball’s “unwritten rules” act as a monolithic, de facto system that

effectively maintains Western culture as the superior epistemological belief system and value