1

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

COMMUNICATING AND CO NTROLLING STRATEGY:

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF

THE BALANCED SCORECARD

Mary A. Malina

University of Melbourne

and

Frank H. Selto

University of Colorado at Boulder

University of Melbourne

APPEARS IN JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING RESEARCH, V. 13, 2001

We gratefully acknowledge helpful comments from Luke George, David Guenther, Marlys Lipe,

Peter Luckett, Bill Maguire, Axel Schulz, Phil Shane, Naomi Soderstrom, and Wim Van Der Stede,

workshop participants at the University of Colorado, University of Melbourne, AAANZ 2000 and

AAA 2000, and, in particular, the two anonymous reviewers who gave consistently insightful and

constructive comments. This research was supported by a Hart Doctoral Fellowship from the

University of Colorado at Boulder and by data generously provided by the anonymous host

company.

1

COMMUNICATING AND CONTROLLING STRATEGY:

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF

THE BALANCED SCORECARD

ABSTRACT

This paper reports evidence on the effectiveness of the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) as a strategy

communication and management-control device. This study first reviews communication and management

control literatures that identify attributes of effective communication and control of strategy. Second, the

study offers a model of communication and control applicable to the BSC. The study then analyzes empirical

interview and archival data to model the use and assess the communication and control effectiveness of the

BSC. The study includes data from multiple divisions of a large, international manufacturing company. Data

are from BSC designers, administrators, and North American managers whose divisions are objects of the

BSC. The study accumulates evidence regarding the challenges of designing and implementing the BSC faced

by even a large, well-funded company. These findings may be generalizable to other companies adopting or

considering adopting the BSC as a strategic and management control device.

Data indicate that this specific BSC, as designed and implemented, is an effective device for controlling

corporate strategy. Results also indicate disagreement and tension between top and middle management

regarding the appropriateness of specific aspects of the BSC as a communication, control and evaluation

mechanism. Specific results include evidence of causal relations between effective management control,

motivation, strategic alignment and beneficial effects of the BSC. These beneficial effects include changes in

processes and improvements in both the BSC and customer-oriented services. In contrast, ineffective

communication and management control cause poor motivation and conflict over the use of the BSC as an

evaluation device.

Data availability: Use of all data collected for this study is regulated by a strict non-disclosure agreement,

which requires the researchers to protect the company’s identity and its proprietary information.

2

COMMUNICATING AND CONTROLLING STRATEGY:

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF

THE BALANCED SCORECARD

INTRODUCTION

The professional and academic strategy literatures claim that many organizations have found traditional

performance measures (e.g., ex post costs, profits, and return on investment) to be insufficient guides for

decision making in today’s rapidly changing, hyper-competitive environment. Sole reliance on current,

financial measures of performance arguably does not reflect the importance of current resource decisions for

future financial performance [e.g., Dearden, 1969]. Though some firms recognized the importance of non-

financial measures of performance many years ago (e.g., General Electric in the 1950s), growing international

competition and the rise of the TQM movement have widened the appeal of non-financial performance

measures. Since the 1980s, authors have filled the professional and academic literature with recommendations

to rely more on non-financial measures for both managing and evaluating organizations [e.g., Johnson and

Kaplan, 1987; Berliner and Brimson, 1988; Nanni et al., 1988; Dixon et al., 1990; Rappaport, 1999].

In addition to normative arguments, empirical research can help to establish the roles and effectiveness

of non-financial performance measurement. A number of studies have sought to link specific non-financial

measures to financial performance (e.g., Banker et al., 2000; Behn and Riley, 1999; Foster and Gupta, 1999;

Ittner and Larcker, 1998a).

1

Evidence in the human resources literature shows that systems of non-financial

measures, not individual measures themselves, appear to be more reliable determinants of firm performance.

(e.g., Becker and Huselid, 1998; Huselid, 1995, 1997). The objective of this study is to examine the process

and impact of managing an organization with non-financial performance measures, specifically in the context

of the balanced scorecard (BSC), which is a comprehensive system of performance measurement.

The BSC, popularized by Kaplan and Norton [1992, 1993, 1996a, b, c] and adopted widely around the

world, has been offered as a superior combination of non-financial and financial measures of performance.

2

Because the BSC explicitly focuses on links among business decisions and outcomes, it is intended to guide

strategy development, implementation, and communication. Furthermore, a properly constructed BSC could

provide reliable feedback for management control and performance evaluation.

Atkinson et al. [1997] regard the BSC as one of the most significant developments in management

accounting, deserving intense research attention. Silk [1998] estimated that 60 percent of the U.S. FORTUNE

500 companies have implemented or are experimenting with a BSC. Given its high profile, surprisingly little

academic research has focused on either the claims or outcomes of the BSC [Ittner and Larcker, 1998b]. A

natural question is: does the BSC’s content, format, implementation, or use have discernable effects on

3

business decisions and outcomes that could not be attained with existing measures, alone or in combination?

In the first study of its kind, Lipe and Salterio [2000] identify decision effects associated with the format of

the BSC. The arrangement of performance measures into four related categories appears to convey decision-

relevant information to subjects performing a laboratory evaluation task. Most other current BSC studies,

however, are relatively uncritical descriptions of BSC adoptions.

Kaplan and Norton [1996] argue that the BSC is not primarily an evaluation method, but is a strategic

planning and communication device to (1) provide strategic guidance to divisional managers and (2) describe

links among lagging and leading measures of financial and non-financial performance. The BSC purports to

describe the steps necessary to reach financial success; for example, invest in specific types of knowledge to

improve processes. If the links are valid reflections of a company’s administrative and productive processes

and economic opportunities, the BSC embodies and can communicate the company’s operational strategy.

Furthermore, effectively communicating these links throughout the organization can be crucial to

implementing that strategy successfully [Tucker et al, 1996; West and Meyer, 1997]. Organizations also might

use non-financial measures as the basis of performance evaluation. Alternatively, they might improve

performance by using the BSC as a guide to financial success and by also judicially using financial

performance measures for evaluation purposes [e.g., Rappaport; 1999].

The present study investigates the communication and management-control attributes and the

effectiveness of a large, successful, international company’s BSC model. The study includes archival and

qualitative data from interviews with the BSC’s designers, managers, and users to (1) assess the perceived

attributes of the BSC as both a strategic communication and control device and (2) find evidence of the

BSC’s decision impacts. The current study does not test whether the company’s BSC is a statistically valid

model of the company’s activities and performance. This feature of the BSC will be tested in subsequent

research [Malina, 2001].

The company introduced the BSC to advance its strategy. The scorecard has greatly affected the outlook

and actions of users, both beneficially and adversely. When elements of the BSC are well designed and

effectively communicated (according to criteria described in the study), the BSC appears to motivate and

influence lower-level managers to conform their actions to company strategy. Furthermore, managers believe

that these changes result in improved sub-unit performance. However, there also is consistent evidence that

flaws in the BSC design and shortcomings in strategic communication have adversely affected relations

between some top and middle managers. The tension exists because the BSC design exacerbates strong

differences between their views of future opportunities. Shortcomings in communication generate mistrust

and unwillingness to change. While the specific flaws and shortcomings may be unique to the studied

company, these findings appear to reflect generally on issues of BSC design and uses.

4

The second section of this paper develops a research question from a review of the communication

literature regarding characteristics of effective communication of strategy. The third section develops a

second research question through an overview of attributes of management control devices that effectively

control strategy. The fourth section describes the research site and the company’s BSC. The fifth section

describes procedures used to obtain and analyze the archival and qualitative interview data. This section also

presents a theoretical model to describe BSC effectiveness. The sixth section addresses the research questions

and derives an empirical model of BSC effectiveness. The final section summarizes conclusions and offers

recommendations for future research.

THE BSC AND COMMUNICATION OF STRATEGY

Kaplan and Norton [1996c] state that, “by articulating the outcomes the organization desires as well as

the drivers of those outcomes (by using the BSC), senior executives can channel the energies, the abilities, and

the specific knowledge held by people throughout the organization towards achieving the business’s long-

term goals.” Thus, Kaplan and Norton assert that not only does the BSC embody or help create

organizational strategy and knowledge, but also the BSC itself effectively communicates strategy and

knowledge. Merchant [1989] argues that communication failure is an important cause of poor organizational

performance. Because no organization’s knowledge or strategy exists apart from or succeeds without its key

human actors, the ability to effectively communicate may be itself a source of competitive advantage [Tucker

et al., 1996; Daft and Lewin, 1993; Grant, 1991; Schulze, 1992; Amit and Shoemaker, 1990]. If the BSC does

articulate organizational knowledge and strategy in a superior manner, then it may be a source of competitive

advantage, at least until all competitors use it equally well. The organizational communication literature,

however, identifies a complex set of characteristics that affect the quality or effectiveness of communication

in organizations.

Based on a review of the literature, an organizational communication device or system may be

characterized by the attributes of its (1) processes and messages, (2) support of organizational culture, and (3)

creation and exchange of knowledge. Brief reviews of these communication characteristics follow.

Communication Processes and Messages

Individuals use and rely on communication if its processes and messages are perceived as understandable

and trustworthy. Other characteristics of effective organizational communication processes are routineness,

predictability, reliability, and completeness [Barker and Camarata, 1998; Goodman, 1998; Tucker, et al., 1996].

Communication also is more effective if it uses concise messages and clearly defined terms [Goodman, 1998].

Furthermore, an effective communication system precludes suppression of truth or misstatement of

performance. There should be no ambiguity regarding the differences between truthfulness and “looking

good” or integrity with winning. The effective communication system and its users will be intolerant of “spin,

5

deniability, and truth by assertion” [Goodman, 1998]. Therefore, organizational communication will be

effective if processes and messages are valid representations of performance. Effective communication and

effective performance measurement conceptually overlap, as was discussed previously.

Support of Culture, Values, and Beliefs

The traditional view of effective organizational communication is that it supports organizational culture

and individual interest by reinforcing desired patterns of behavior, shared values, and beliefs. Effective

communication demonstrates that the organization does what it says and that individual or group rewards are

predicated on their actions [Tucker, et al, 1996; Goodman, 1998]. Communication by leaders that consistently

articulates shared goals, values and beliefs [Tucker, et al, 1996; Goodman, 1998] also is effective in reinforcing

culture and directing behavior. Furthermore, effective communication must encourage behavior consistent

with organizational goals, values, and beliefs [Goodman, 1998].

Proponents of the BSC [e.g., Kaplan and Norton, 2000] argue that it also can be an instrument of cultural

and strategic change. Consistent with Kotter’s [1995] observations of change processes, the BSC may

facilitate change by effectively creating and communicating a credible vision of and method for achieving

change.

Creation and Exchange of Knowledge

Knowledge, which may be objective or tacit, is the basis of strategy formulation and implementation.

3

Therefore, an effective communication system supports an organization’s strategy by nurturing both objective

and tacit knowledge. The effective communication system exchanges objective (observable) knowledge

among key individuals so that all are aware of the organization’s current status. Organizations create objective

knowledge from the development and integration of new knowledge by individual specialists. Objective

knowledge usually derives from the refining and sharing of individuals’ tacit knowledge, which is understood

but not yet articulated or usable by the organization. Therefore, an effective communication system

encourages and enables the sharing of individuals’ experiences and collects those shared experiences. This

may be best accomplished by intense and frequent sharing, and by dialogue rather than one-directional

reporting. Perhaps importantly for the effectiveness of the BSC, de Haas and Kleingeld [1999] argue further

that participation in the design of performance measurement systems is an important determinant of effective

communication of strategy.

In summary, effective organizational communication devices should possess the observable attributes of

• Valid messages – reliable, understandable, trustworthy

• Support of organizational culture – existing or changing

• Knowledge-sharing – including dialogue and participation

6

The organizational communication literature predicts that a BSC, which has these attributes, will create

strategic alignment, positive motivation, and positive organizational outcomes. The first research question is:

1. Is the BSC an (in)effective communication device, creating strategic (non)alignment,

(in)effective motivation, and (negative)positive organizational outcomes?

THE BSC AND MANAGEMENT CONTROL OF STRATE GY

A common criticism of managing organizations based on financial measures of performance is that these

measures induce managers to make myopic, short-run decisions. Financial measures tend to focus on the

current impacts of decisions without a clear link between short-run actions and long-run strategy [recent

criticisms include McKenzie and Schilling, 1998; Luft & Shields, 1999]. Furthermore, traditional financial

measures of performance can work against knowledge-based strategies by treating the enhancement of

resources such as human capital, which may be critical to implementing strategy, as current expenses [e.g.,

Johnson, 1992]. Dixon et al. [1990] argue that traditional financial measures, by expensing costs of many

improvements, also work against strategies based on quality, flexibility, and minimization of manufacturing

time. For many lower-level employees, most financial performance measures are too aggregated and too far

removed from their actions to provide useful guidance or feedback on their decisions. They might need

measures that more directly and accurately relate to outcomes that they can influence [McKenzie and

Schilling, 1998]. A number of studies have found evidence that traditional, financial measures of performance

are most useful in conditions of relative certainty and low complexity – not the conditions faced by many

organizations today [e.g., Gordon and Naranyan, 1984; Govindarajan, 1984; Govindarajan and Gupta, 1985;

Abernethy and Brownell, 1997].

Lynch and Cross [1995] argue that performance measures should motivate behavior leading to

continuous improvement in key areas of competition, such as customer satisfaction, flexibility, and

productivity. That is, they should reflect cause and effect between operational behavior and strategic

outcomes [Keegan et al, 1989; Ittner and Larcker, 1998a].

4

Furthermore, as an organization identifies new

strategic objectives, it also may realize a need for new performance measures that encourage and monitor new

actions [Dixon et al., 1990]. Thus, organizations sensibly and perhaps optimally may use a diverse set of

performance measures to reflect the diversity of management decisions and efforts [e.g., Holmstrom, 1979;

Banker and Datar, 1989; Feltham and Xie, 1994; Ittner and Larcker, 1998b]. Empirical support for these

propositions is limited but growing.

5

The Management-Control Case for the Balanced Scorecard

Kaplan and Norton [1996b] have arranged multiple performance measures into the Balanced Scorecard,

which is a logical expression of most models of western business management.

6

Indeed, the BSC may have

7

spread widely throughout the world on the strength of its intuition and internal logic. Kaplan and Norton

claim that the BSC offers two significant improvements over traditional financial or even non-financial

measures of performance.

First, the BSC identifies four related areas of activity that may be critical to nearly all organizations and all

levels within organizations:

• Investing in learning and growth capabilities

• Improving efficiency of internal processes

• Providing customer value

• Increasing financial success

Following the logic of the BSC and ignoring cost-benefit considerations, most organizations could use

measures in all four areas to encourage and monitor actions appropriate to organizational strategy. In its most

basic use, a properly configured BSC could provide a comprehensive picture of the state of the organization,

much as an automobile’s dashboard shows fuel level, oil pressure, coolant temperature, engine RPM, and

velocity. Thus, the BSC might promote positive organizational outcomes such as improvements in all four

areas of organizational activity, which include administrative activities and the BSC itself. Assessing this first

level of effectiveness is the objective of this research.

Furthermore, the BSC seeks to link these measures into a model that accurately reflects cause and effect

relations among categories and individual measures. Using the automobile analogy, the BSC simulates a

change in a car’s performance (e.g., velocity) given a planned increase in fuel consumption and engine RPM

(and perhaps other factors). Such a model might support operational decisions, make predictions of

outcomes given decisions and environmental conditions, and provide reliable feedback for learning and

performance evaluation.

7

The Role of the BSC for Strategy Implementation and Performance Measurement

Proponents of the BSC stress its alignment of critical measures with strategy and links of the measures to

valued outcomes. In addition, the management control literature identifies other characteristics of control

systems that may be critical to the successful implementation of strategy and should apply to the BSC.

8

To be

effective, BSC measures should be accurate, objective, and verifiable. Otherwise, measures will not reflect

performance and may be manipulated, or managers could in good faith achieve good measured performance

but cause the organization harm. If managers can achieve good measured performance by cheating, the

system quickly will lose credibility and desired motivational effect. Furthermore, the set of BSC measures

should completely describe the organization’s critical performance variables, but should be limited in number

to keep the measurement system cognitively and administratively simple. An exhaustive set of performance

measures may accurately reflect the complexity of the organization’s tasks, but too many measures may be

8

distracting, confusing, and costly to administer. However, Lipe and Salterio [2000] did not find evidence of

information overload from multiple measures in their experimental study of the BSC.

Positive motivational impact induces managers to exert effort to achieve organizational goals. While

informative but not controllable performance measures may be important, positive motivation requires that

at least some of the BSC measures should reflect managers’ actions. For example, relative performance

evaluation (e.g., across similar business units), which can identify “influenceable” but not completely

controllable outcomes, may be an important component of the BSC [e.g., Antle and Demski, 1988], but it

may not be sufficient by itself. Extensive goal-setting literature confirms that performance should be keyed to

challenging but attainable targets [e.g., Locke and Latham, 1990]. Without such explicit BSC targets,

performance likely would be lower than could be reasonably achieved. Finally to build goal commitment, the

BSC should be linked with prompt and well-understood rewards and penalties. Rewards that are delayed,

uncertain, or ambiguous may be ineffective motivational devices.

Therefore, even though an organization’s BSC reflects its critical performance variables and links to

valued outcomes, it may fail as an effective management control device if it lacks other attributes. For

example, Ittner et al. [2000] found that subjectivity in a bank’s BSC led to both its having little beneficial

impact and the bank’s reversion to short-term financial measures of performance. To summarize, an effective

management control device, which is capable of promoting desired organizational outcomes, should have the

following, observable management control attributes to, first, attain strategic alignment:

• A comprehensive but parsimonious set of measures of critical performance variables, linked with

strategy

• Critical performance measures causally linked to valued organizational outcomes

• Effective – accurate, objective, and verifiable – performance measures

Second, to further promote positive motivation, an effective management control device should have

attributes of:

• Performance measures that reflect managers’ controllable actions and/or influenceable actions, e.g.,

measured by absolute and/or relative performance

• Performance targets or appropriate benchmarks that are challenging but attainable

• Performance measures that are related to meaningful rewards

Management control theory predicts that, if the BSC has these attributes, it is likely that the BSC will promote

strategic alignment and positive motivation and outcomes. Therefore, the second research question, which

parallels the first, is:

2. Is the BSC an (in)effective management control device, creating strategic (non)alignment,

(in)effective motivation, and (negative)positive organizational outcomes?

9

Subsequent discussions elaborate the details of a model that reflects the two research questions. This

model, based on the literature review, shows that the BSC’s management control and communication

characteristics generate outcomes by creating strategic alignment and motivation (or not). This study also

describes efforts to collect data on an implemented BSC’s management control and organizational

communication attributes, as well as evidence on the BSC’s effects on strategic alignment, motivation, and

organizational outcomes. It is bold to judge the effectiveness of the BSC against evidence from a single, non-

experimental BSC implementation. However, a thorough examination of a critical case can be instructive and

generalizable to theory [i.e., analytical generalization, Yin, 1994: 30-32], which in this case is that the BSC can

be an effective strategy communication and management control device.

RESEARCH SITE AND BSC CHARACTERISTICS

Overview of the Research Site

The research site is a U.S. FORTUNE 500 company with more than 25,000 employees and $6 billion

sales of durable products and post-sale services. The company is regarded as a long-term, well-managed

company. It is succeeding in highly competitive domestic and foreign markets, characterized by competition

among relatively few, very large, international companies. The company recently adopted a customer- and

quality-driven strategy to improve its competitiveness, and consequently perceived a need to expand its

management controls and performance management beyond traditional, financial measures. The company

began changing its performance measurement systems with a BSC that focuses on a very important part of

the company. One and a half years before the start of this study, the company began its implementation of a

Distributor-BSC (DBSC), for its 31 North American distributorships, which are responsible for a large share

of the company’s sales. The company has sufficient resources to assign BSC responsibilities to key staff that

are championing its continued development and implementation. These staff members have had formal BSC

training and are not using services of outside consultants. The DBSC was developed centrally and imposed

on the distribution channel, with little initial input from distributors themselves.

The company’s distributors in North America have primary responsibility for retail sales and service of

company products. Distributorships are organized by geographical area and may not sell other companies’

competing products. Although they are independently owned, individuals with employment experience in the

company currently lead 30 of the 31 distributorships. Distributors operate under renewable three-year

contracts with the company, which are based on realized and expected future performance.

9

The authors gained access to this company because of a family relationship between one of the authors

and executives of the company.

10

In this sense the field study is serendipitous, but the site is attractive on a

priori, objective grounds, and would have been a top candidate in a purposive sampling approach.

11

10

To summarize, the company has a long history of effective management control, extensive resources, and

a commitment to communicate its strategy to its distributors. Furthermore, early in the investigation

researchers perceived considerable tension and possible resistance to change among parties affected by the

DBSC, which, as Ahrens and Dent [1998] counsel, usually makes for an engaging study. Thus, the company

and its DBSC project are ideal for field study research on the balanced scorecard.

Overview of the DBSC

Purpose of the DBSC

In line with its new customer-driven strategy, the company recently changed its distribution strategy from

one of operational efficiency to managing long-term customer relations. Until the DBSC, the company had

evaluated formal distributor performance solely on financial performance and market share. Company

documents and literature show that staff personnel designed the DBSC, top-down without input from

distributors, to communicate the company’s new retail distribution strategy to its distributors. Company

documents state the purposes of the DBSC are to:

• Highlight areas within distributorships that need improvement to enhance customer relations

• Provide an objective set of criteria, consistent with the company’s new strategic initiatives, to

guide and measure total distributor performance.

These purposes fall well within the scope of the use of the BSC as envisioned by Kaplan and Norton.

However, administrators who developed and use the DBSC describe two additional objectives, which have

far reaching implications for managing the company’s distribution system:

• DBSC performance will be used as the starting point for the three-year contract review process.

• The DBSC is used for comparing and ranking distributorships and may be used for

performance-based compensation.

Because the DBSC includes many previously unevaluated areas of performance, it represents a dramatic

change in communication, interactions, and formal relations between the company and its distributors. In

particular, using the DBSC for distributor contract renewal and compensation added significant economic

incentives and created uncertainty regarding the impacts of DBSC performance.

Structure of the DBSC

The DBSC contains measures of performance in each of the four BSC perspectives plus another for

corporate citizenship, which the company felt was lacking in Kaplan and Norton’s specification of the BSC.

12

Additionally, the company has arranged its DBSC measures in categories that reflect its own priorities and

culture. Though distributors prepare some DBSC measures in “real time,” the company staff compiles,

analyzes, and disseminates the DBSC quarterly to top management and to distributors. An internal document

(usual BSC categories shown in brackets) describes the DBSC as:

11

“…comprised of measures that are categorized into groups which are aligned with [the company’s strategic]

objectives: Competitive Advantage [customer value and internal processes], Profitability and Growth [internal

processes and financial success], Corporate Citizenship, and Investments in Human Capital [learning and

growth]. A fifth category has been added to include other measures important to distributor performance

[internal processes]. Each of the categories includes specific measures with specific criteria for acceptability.

The results for the measures within each category will be weighted to determine an overall score for each

category and an overall score for the distributorship.”

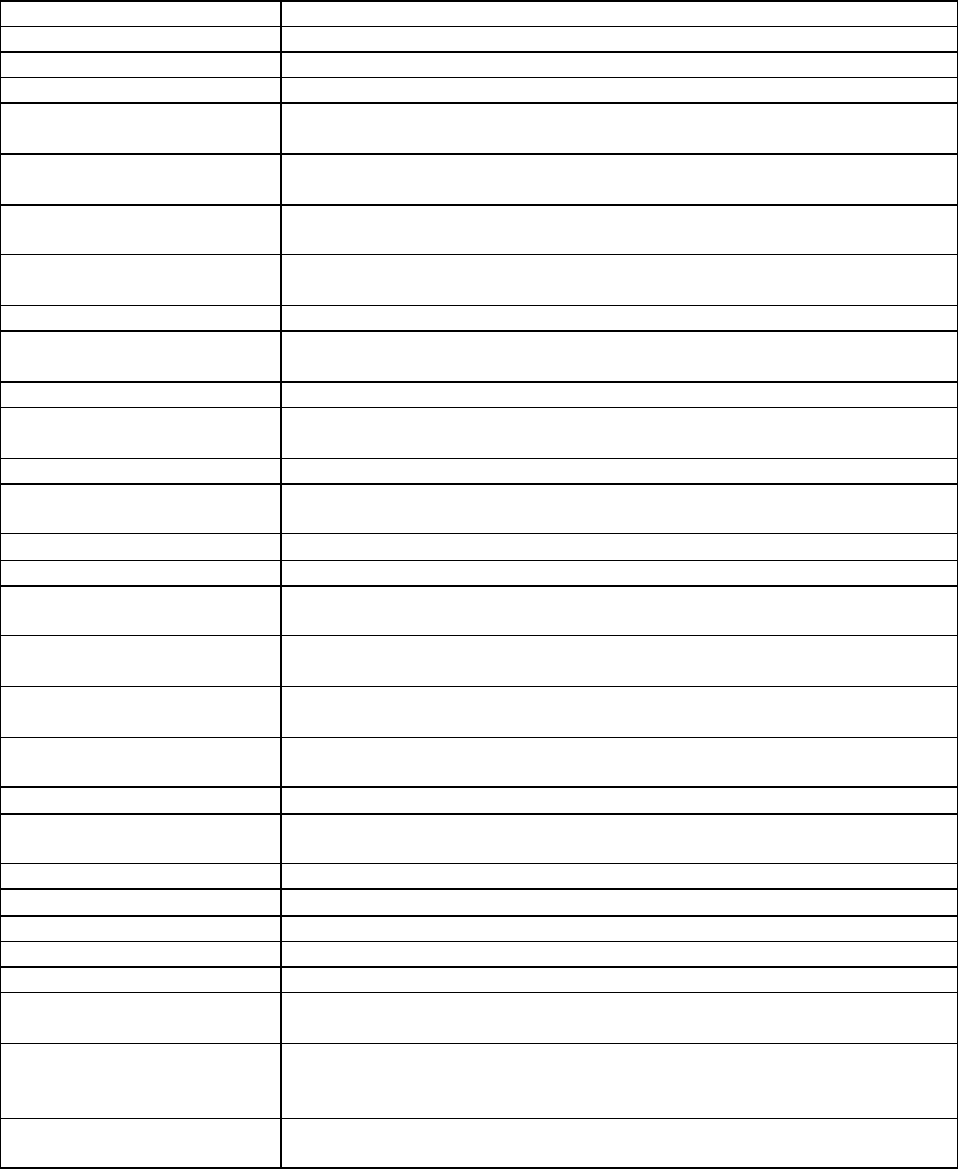

A summary of the measures and the weights currently used in the DBSC are in table 1. For comparability

with the literature, we have arranged these measures into the usual BSC categories, but we also note where

the company has placed them in its own categories.

TABLE 1

DBSC Measures and Approximate Weights

Both distributors and DBSC administrators understood immediately that the DBSC’s relative weights

reflect the company’s view of the most important areas of performance.

13

Distributors’ knowledge of “why”

came later, if at all, as will be seen. Additionally and with experience, the company revised the weights to

reflect learning about measures’ impacts, reliability, or possible manipulation, particularly of some of the

softer measures, as Flamholtz [1979] predicts. One of the principal designers of the DBSC stated:

“Changes in weights are a function of two things: 1) how important we think the things are; 2) how credible the

numbers we get are…. How do we measure outstanding people at the distributor? It’s important, but how

substantive a measure can we come up with for it? Hardness of the number definitely affects the weights. If

we place a heavier weighting on something you don’t have confidence in, is that better than now?” [11:71-83].

One of the key managers of the distribution channel also explained:

“Now market share really is the driver and means more than the other things do. We did move more of the

weighting there. It’s more important to reflect the feeling of the management team. The distributors say, tell me

how you’re ranking me, and I’ll do it even if I don’t like it.” [12: 143-149]

The company’s first version of the DBSC placed a total of 20 percent weighting on Investments in human

capital (learning and growth area), but after a year that weight had been reduced to only 4 percent, primarily

because management felt the numbers were unreliable. Likewise, the first scorecard placed a 10 percent

weighting on Corporate citizenship (internal processes and customer value areas), later reduced to 4 percent. The

company redistributed the original weightings mostly to the traditional market share measure (an outcome of

building customer relationships), which grew in importance from 12 percent to 28 percent, to reflect the

paramount importance of building long-term customer relationships that result in market share. The

company also has added weight to quickly diagnosing and solving customer problems (internal processes

12

area), which grew from 2 percent to 10 percent in importance, to reflect the company’s belief about an

essential element for building customer relationships. As discussed later, the weightings and changes in

weighting affected distributors’ perceptions about both the “balance” in the DBSC and the truly important

measures of importance.

Management did not consider distributors to be partners in the process of developing the DBSC, which

reflected the company’s traditional, top-down approach to management. A more open, participative approach

to the development and use of the DBSC (one attribute of effective communication) could have had an

impact on distributors’ acceptance of the DBSC’s and their subsequent performance. Furthermore, the

company did not explicitly design the DBSC to be a “strategy map,” in Kaplan and Norton’s [2000]

terminology,

14

but let the measures and weights “speak for themselves” as key performance indicators. The

top-down and ambiguous nature of the communication may have impeded the immediacy and effectiveness

of the DBSC message. As will be demonstrated later, distributors had strong feelings on this, which can

explain adverse impacts of the DBSC.

Figure 1 shows a quarterly DBSC, as reported to management for several representative distributors. This

scorecard, which is based on numerical measures, is notable for several reasons. First, each distributor’s

quantified and internally benchmarked performance measure is labeled and colored “red” for “fails to meet

criteria for acceptability”, “yellow” for “meets criteria for acceptability”, or “green” for “exceeds criteria for

acceptability.”

15

The total score in the last column is computed by multiplying each measure’s numerical score

by the appropriate weights. Second, each distributor obtains its own report and its relative, numerical ranking

(e.g., 7

th

out of 31). Furthermore, names of distributors that achieve “green” ratings are posted on the

company’s intranet for all to see.

16

FIGURE 1

Representative Distributor BSC Ratings and

Scores

RESEARCH METHOD

This study investigates its research questions with qualitative, interview data obtained from individuals

directly involved with the company’s DBSC. Thus, the evidence is perceptual in nature and, while it ideally

reflects the “reality” of the impact of the DBSC, it also may reflect individuals’ and researchers’ biases in ways

that are not easily detectable. The study’s research method attempted to mitigate the effects of these

unknown biases. The research method is described below.

17

Sampling

Because the DBSC represents a dramatic change in distribution strategy from operational efficiency to

managing customer relationships by the company’s distributors, we sought and obtained direct commentary

13

from two DBSC designers, three managers who use it to evaluate distributors, and nine of the 31 distributors.

Because the research is interested in all facets of the DBSC, the scope of the distributor sample is limited to

those who consistently reported complete or nearly complete data. At the time of the study, these distributors

had the full six quarters’ experience with the DBSC. While added experience may continue to refine

perceptions, the sampled distributors represent the most experienced distributors available at the time of the

study. This selection may bias the analysis if more experienced distributors that also report more complete

data have systematically different perceptions than other distributors. Another source of bias may be

scorecard performance, which could influence perceptions of the DBSC; the sample included nine

distributors who reflected overall red, yellow, and green ratings. Of the distributors reporting complete data,

only one “green” distributor was available and three “red,” so the sample was filled out with five “yellow”

distributors. At the time of the interviews, overall there were 2 green, 19 yellow, and 10 red distributors. The

sample also reflected geographic dispersion – three western, two midwestern, two southern, one northeastern

US, and one Canadian distributor.

After analyzing the interviews, we feel confident that we have obtained a

full range of distributor responses. As the interviews proceeded, responses became repetitive. While

additional “green” distributor interviews would have been desirable, we feel they would be unlikely to

contribute additional insights.

18

Data Collection

The researchers obtained archival data (background and policy documents and quarterly DBSC scores)

from managers who administer the DBSC. All interview data were obtained via telephone in mid-1999 after

sponsoring managers informed designers, other managers, and all 31 distributors that the researchers were

conducting this study and may call them for input about the DBSC. Interviews lasted from 45 minutes to 75

minutes, depending entirely on how much an interviewee had to say. The study used a semi-structured

interview format and assured respondents of anonymity.

19

To avoid responses that could be artifacts of the interview process itself, the researchers deliberately did

not ask leading questions regarding management control or communication attributes of the DBSC or

questions directly related to the study’s research questions. While the study’s use of management control and

organizational communication theories represents a deductive approach to research and does guide later

analysis and model building, we were not confident that we had identified all relevant factors related to the

effectiveness of the DBSC. At this stage, we preferred to gather data more freely and let the respondents’

natural, undirected commentary support, deny, or extend the theories.

20

An important benefit of this

approach is that respondents may identify factors that affect the effectiveness of the DBSC other than those

anticipated by the study’s theory.

The researchers asked each distributor the following open questions:

1. In your own words, what is the distributor-balanced scorecard?

14

2. What do you think the objective of the balanced scorecard is?

3. What are the nine measures that distributors report really measuring?

4. What are the measures that are filled out by the company really measuring?

5. How do the measures that distributors report relate to the company’s measures? (Follow up: Do

changes in distributor performance cause changes in the company’s measures?)

6. Do the measures (distributors’ and the company’s) help you in any way? (Follow up: How?)

7. Are there any benefits from the balanced scorecard itself? (Follow up: Apart from the individual

measures?)

8. Do you have any (other) recommendations for improving the balanced scorecard?

The researchers asked essentially the same questions of administrators of the DBSC, but their interviews

tended to be more open and wide-ranging. To keep within the time available, the researchers usually did not

ask the administrators questions about specific DBSC measures (questions 3 and 4). Thus, distributor and

administrator interviews are not directly comparable on all questions. Because the administrator interviews are

less focused on the DBSC measures, this study uses them for background information. Unless otherwise

indicated, the analyses that follow refer to the distributor interviews only.

The interviews were conducted via conference calls conducted over a three-week period, with one

researcher asking initial and follow-up questions and the second researcher taking notes and capturing the

commentary on a laptop computer. After each interview, the two researchers conferred immediately to

complete abbreviated comments that might be difficult to decipher later. Interview files were copied intact

and archived in several locations.

Coding Interview Data

Coding Procedures

Two alternative coding procedures are (1) completely free coding unconstrained by prior theory or (2)

strict use of codes based on theoretical constructs. Both approaches have their adherents. However, it is

unusual for accounting researchers to enter the field free from preconceptions or prior theory. Miles and

Huberman [1994] argue that, when theory guides inquiry, it is efficient and realistic to begin with a conceptual

framework, and add “free” codes as the data suggest. The result is a hybrid approach that acknowledges

theoretical guidance (or bias) and permits empirical flexibility (or theory revision). The research used the

management control and organizational communication literatures surveyed earlier as a coding and analysis

guide, but modified the framework as the researchers delved into the data. Thus, the study contains elements

of both theory building and testing.

The computerized analysis method applies codes that reflect theoretical or empirical constructs to the

qualitative data – a sophisticated way to annotate and generalize interview transcripts. The researchers

predetermined codes for the interview data to reflect the interview questions – questions 1, 2, 4 to 8 and

15

twelve distributor-supplied measure questions for question 3.

21

The researchers also created codes that reflect

expected management control factors (e.g., Causality among measures), attributes of organizational

communication (e.g., Supports company culture), and impacts of the DBSC (e.g., Measure causes change). As

discussed earlier, some codes reflect additional concepts, revealed in the coding process (e.g., Weight of each

measure in determining overall DBSC scores). These codes were then applied to the interview data as

illustrated in Figure 2.

22

The study did not use the software specifically to search for or count specific words

or phrases. Choice of vocabulary is arbitrary, and words or phrases may not carry meaning outside of their

spoken context [Miles and Huberman, 1994]. Analysis, therefore, required reading, understanding, and coding

blocks of text in the context of each interview. This is the most subjective stage of the analysis, but in

addition to using both an interview protocol and a coding scheme the researchers took other steps to increase

the objectivity of the coding. Appendix 2 details these steps of the analysis.

FIGURE 2

Example of Coded Interview Text

The final list of codes, with frequencies by interview, is in table 2. Observe that for ease of later

exposition, the study collects related individual codes into large-pattern codes or “supercodes.” These

supercodes reflect ex ante theoretical constructs (e.g., Effective communication, Effective management control, Positive

outcomes) and are analogous to statistical factor models. The frequencies of the codes are an indication of

relative importance of each of these concepts, but frequency does not reflect intensity of feelings, nor does it

reflect relations among concepts. These attributes of the data may be discovered through additional analyses,

which are described next. One or a few talkative respondents did not dominate the coded comments, though

one distributor’s interview was briefer than the rest.

TABLE 2

Interview Codes and Frequencies by Interview

Relations Among Codes

Theoretically Supported Model

Figure 3 is a model of relations among employees’ perceptions of the management control and

organizational communication attributes of the DBSC that is based on the prior literature review and codes

applied during analysis. The arrows (? ) between the boxes reflect expectations about causal relations. The

research expected that both Effective management control and Effective communication in the design and use of the

DBSC would cause Strategy alignment, Effective motivation, and, ultimately, Positive outcomes. In contrast, the

16

research expected that “ineffective” factors could cause “negative” outcomes (in this case, only Conflict/tension

was observed qualitatively and coded

23

).

FIGURE 3

Theoretical Model of Management Control,

Communication, and the BSC

Observing Relations Among Codes

The relational-query capabilities of qualitative software, such as Atlas.ti, permit extensive exploration of

associations and possible causal hypotheses using coded interviewees’ perceptions of the DBSC. Assessing

the degree of relation among codes requires analysis of proximity and context of hypothesized relations (as in

figure 3). This is analogous to building a correlation table using a set of statistical measures, where the

frequency and nature of qualitative associations are building blocks of causality. The study assessed causality

by testing for multiple qualitative attributes of causal relations. Appendix 2 details the steps used to

operationalize this approach to analyzing and establishing evidence of causality within the study’s research

questions.

RESULTS

It is clear that distributors are aware of and understand the company’s diagnostic objective for the overall

DBSC. Representative comments that explain their awareness of the new measures and their links include:

“A lot of businesses tend to run with financial and market share measures, but those are pretty crude handles.

We have to get underneath with measures like quality and cycle time, and softer things like employee

development. That’s where the leverage of the business is. The others are results of what you’ve done” [3:154-

158].

24

“I think they are all linked. It’s hard to be a good manager in one area and not another” [9:118-119].

The first objective of this study is to find if the DBSC is perceived to possess the attributes of effective

organizational communication and management control devices. The second objective is to determine

whether these attributes can be causally related to goal alignment, motivation, and reported process or

decision changes.

As detailed in Appendix 2, where the research found specific, consistent, frequent patterns of association, the

researchers looked for further evidence of causality, based on coherence,

25

which is closely related to face

validity. This credible “story” of coherent causality is what distinguishes between findings of causality or mere

association. Table 3 and figure 4 summarize the results of an exhaustive audit of the coherence of specific,

consistent, and frequent associations.

These exhibits contain only those associations found to meet sufficient

causality criteria (complete data are in Appendix 2).

17

TABLE 3

Summary of Distributor-Response Supercode

Associations

FIGURE 4

Empirical Model of Distributors’ BSC

Perceptions

Overview of Data-Supported Model

Empirically associated quotations in the interview data, which are reflected by links in figure 4, support

the research questions in interesting ways.

26

Further analysis of all the paired codes in table 3 and figure 4

reveals answers to the study’s research questions and leads to recommendations for improving the

effectiveness of the DBSC.

Trimming the ex ante relations in figure 3, reflected in figure 4, has implications for understanding how

the BSC may cause management control and communication of strategy. On the “effective” side of figure 4,

Effective management control appears to cause Aligned with strategy and Effective motivation, which in turn appears to

cause Positive outcomes (e.g., perception of Improvement). These are consistent, strong associations between

specific factors that tell a coherent story, which the research interprets as evidence of causality. There is,

however, no consistent evidence of a direct link between Effective management control and Positive outcomes. In this

model, Effective management control affects Positive outcomes through Aligned with strategy and Effective motivation.

These data provide support for the “effective” form of the management control research question 2.

Surprisingly, there are no consistent links between perceptions of Effective communication and any other

DBSC model factor, which provides no support for the “effective” form of the communication research

question 1. In this case, the effective communication aspects of the BSC appear to be redundant to effective

management control.

On the “ineffective” side of the model, Ineffective management control, Ineffective communication, and Ineffective

motivation are associated or appear to be causally related. Furthermore, they appear to cause Conflict/Tension,

which provides support for “ineffective” forms of both research questions 1 and 2. This indicates that poorly

designed and implemented features of the BSC can do harm to the communication and control of strategy.

Several causal links involving Ineffective motivation and other factors were unexpected and will be discussed later.

The research now addresses each of the causal and associative links in the context of the two research

questions, referring to links in figure 4.

Question 1: Is the BSC an (in)effective communication device, creating strategic (non)alignment,

(in)effective motivation, and (negative)positive organizational outcomes?

18

Effective Communication ? Strategy Alignment / Effective Motivation ? Positive Outcomes

Unexpectedly, the study found no consistent evidence of specific relations between the attributes of

Effective communication and other DBSC-model factors. Overall this study does not support the “effective”

form of research question 1 that Effective communication is either associated with or causes Strategic alignment,

Effective motivation, or Positive outcomes.

27

Ineffective Communication ? Strategy Non-alignment / Ineffective Motivation ?

Conflict/Tension

Ineffective communication appeared to be largely independent of other “ineffective” DBSC factors. However,

though the study found little evidence of the impact of Effective communication, there was abundant evidence

that the DBSC administrators’ frequent use of One-way reporting is a direct cause of Conflict/tension (16 causal

links).

Unfortunately, the Conflict/tension appeared to be unproductive (i.e., no consistent links to Positive outcomes).

This may contribute to a climate of distrust and alienation that reduces the company’s and its distributors’

effectiveness. The company imposed DBSC measures and benchmarks without seeking input, and then used

the DBSC as a diagnostic control and an evaluation measure. Distributors felt ignored and trivialized because

of their non-involvement. However, they have little recourse because of the frequency of One-way reporting,

which was a common complaint. For example:

“No response (to my complaints), so we stand by our measure [of safety]. I’ve gotten no response to my

concerns, and I’m ‘PO’d’ at them on this subject. Any distributor who is green is a liar. No realistic way in hell

that that can happen. The nature of the work we do, we just can’t do this…. Do they have any idea what the

distributor environment is? They don’t care enough to reconcile issues, but the factor itself is important” [6:

116-123].

Partly as anticipated, the data provide support for the “ineffective” form of research question 1: Ineffective

communication, specifically One-way reporting, has largely negative consequences for acceptance, perceptions, and

reported uses of the DBSC.

Question 2: Is the BSC an (in)effective management control device, creating strategic

(non)alignment, (in)effective motivation, and (negative)positive organizational outcomes?

Effective Management Control ? Strategy Alignment ? Positive Outcomes.

As expected, BSC characteristics of Effective management control (Effective measurement, Comprehensive

performance, and Weight) appear to be causally linked with Strategy alignment (9 causal links with Key factors, 5 with

BSC important for business, and 9 with Traditional market share, respectively). Distributors perceive that having

reliable data leads to the ability to take actions that affect the new customer-relationship strategy (e.g., 17

causal links with Measure causes change), which might not have been feasible before the DBSC. For example, in

the use of customer satisfaction measures:

19

“We [now] give the work to an outside service. They call a couple of customers every day. We get input on a

list of questions. If the customer ends up not having a good experience, (now) we can get that info that day

and call the customer ourselves” [8: 119-122].

Because the DBSC measures Comprehensive performance, including the key financial and non-financial

measures, it is a reflection of overall success of managing critical factors (BSC important for business). Thus,

managers have a better feel for how they are managing the overall business for both current and future

results.

“The BSC is trying to give us a broader business set of measures of success than the more traditional financial

and market share. It wraps a set of things together that make sense for managing the business” [3: 5-7].

One of the company’s key strategic goals is to increase its traditional market share. The relatively heavy

Weight placed on this DBSC measure forces distributors (sometimes reluctantly) to align their goals with

improving the traditional market segment. They value their relationship with the company, and the DBSC

tells them what they must do to be a successful distributor, though they interpret this to mean they should

pursue improvements in traditional market share to the exclusion of other growth opportunities.

“If they care only about one-third of their business, then that’s good. It’s worth 28 points on the BSC. I’m red

and yellow there so there’s no hope to be green from all the other measures…. They are measuring only

(traditional) market penetration…. Balanced scorecard is certainly a misnomer” [2: 122-126].

By including Key factors, the DBSC causes distributors to diagnose problems and change their processes

and actions (Measure causes change) in significant ways. This leads to numerous recommendations to Modify

measures or BSC (11 causal links) – an example of potential interactive use of the DBSC [e.g., Simons, 2000, ch.

10]. Measuring the percentage of customers’ problems diagnosed within one hour, for example, also caused

most distributors to refocus their parts and service resources to building customer relationships, consistent

with the new strategy, rather than fully utilizing capacity – an example of diagnostic use of the DBSC

[Simons, 2000].

28

“This (measure) differentiates our businesses from our competition. It requires a complete change of ‘culture’

within the shop. Now we have to manage the service event instead of just scheduling work” [1:102-104].

In the past, distributors had favored large, complex service jobs that were relatively easy to schedule and

that could be counted on to occupy technicians and service space for blocks of time. Customers who had

simple service requirements were placed in the service queue in order of arrival, with no preferential

treatment, with the result that many began to take their simple jobs elsewhere and with the risk that they

would be lost as permanent customers. Distributors observed that:

“(One-hour diagnosis) requires a change in measurement and is creating a new mindset within the service

organization…We can’t schedule it; we have to provide the capacity and the process [1: 233-239]. [One-hour

diagnosis] tends to make us triage like a hospital and do the quick jobs first [2: 58-59]. I wasn’t an advocate at

the start, but now I am. It tells us how quickly we figure out what’s wrong so we can make an intelligent

20

statement to the customer, and so they can say ‘go ahead’ or not. We have been able to flow more jobs

through our shop by getting the quick, easy stuff through the shop. It lets us turn jobs quicker and avoids

embarrassing situations…It’s helping us, though it’s not easy to change the mentality, but it’s good” [6: 56-63].

Although there is no evidence of a direct link from Effective management control to Positive outcomes, the data

otherwise provide extensive support for the “effective” form of research question 2. Effective management control

using the DBSC appears to indirectly cause Positive outcomes through Strategic alignment.

Effective Management Control ? Effective Motivation ? Positive Outcomes

The DBSC’s motivational impacts were obvious overall and with respect to specific factors. Incentives

included both improved distributor business performance and successful contract renewals. The management

control design of the DBSC reflects the Causality of the DBSC description of the business, which causes

Meaningful rewards (8 causal links). Distributors believe that improving non-financial DBSC measures will result

in improved customer relationships and significant financial rewards.

“(Service utilization is) the most important number in the whole business [5: 102]. I gave the formula to our

guys that, if we bill our technicians out (on average) one more hour a day, we would put over $X million to our

(annual) bottom line. That’s the kind of magnitude were talking about” [4: 79-82].

29

The DBSC is successful as a motivational tool when it reflects relations between Strategic alignment and

distributor performance. For example, setting Appropriate benchmark targets for motivation goes hand-in-hand

with management control of Key factors (14 association links). Distributors do not object to tough, but

attainable goals.

“Good measurement. Don’t have a problem with that hurdle. Huge issue and can’t stress it enough. We have

about (xxx) labor hours. I can have one (accident) per year to be green. That’s a tight hurdle. It’s probably a

little tight right now” [4: 88-91].

Furthermore, setting attainable but tough DBSC goals (Appropriate benchmarks) motivates distributors to

change their decisions and processes (Measure causes change).

“80% of work is in 4-hour range in our service shop. Great number because the mentality in our shops

had been that we want that big overhaul, the long, lengthy jobs. But then, service efficiency suffers. We didn’t

turn many jobs and lost a lot of hours because there is a good chance of losing hours [on a large job]…Give

the company credit for the four-hour target. They thought about it; it’s probably the industry norm. Fo cusing

on this number has changed some of the culture or at least the thought process in the shop. We changed to the

little jobs and we can get the big jobs later. So our management has awakened to the fact that they can manage

their shops better using the one-hour diagnostic time and four-hour jobs to make their shops more efficient”

[4:47-59].

Relative performance evaluation allows each distributor to know his relative standing and what others are

doing, and thereby motivates distributors and gives them a tool for Improvement (7 causal links).

21

“(Gathering) the information and sharing it back to us, saying other distributors are X. I can look at it and see

how I am doing. Why am I different? I can use it as a lever to try to improve” [7: 123-125].

The data provide consistent evidence of causation and support the contention that perceptions of this

BSC’s effective management control characteristics lead to effective motivation, strategic alignment, and then

positive outcomes, in support of the second research question.

Ineffective Management Control ? Ineffective Motivation ? Conflict/Tension

This study found no consistent or frequent links between any of the elements of Strategy non-alignment and

other DBSC-model factors. However, Key factors that are poorly represented in the DBSC are associated with

numerous examples of other shortcomings. Notably, Inaccurate/subjective measures of Key factors (24 associations)

contribute to perceptions of Inappropriate benchmarks (8 causal links), which appear to cause widespread

Conflict/tension (9 causal links). This nexus of factors appears to be responsible for much of the Conflict/tension

caused by the use of the DBSC (17 out of 33 causal links), which reflected a lack of local autonomy and

participation in determining measures and targets. For example:

“(The measure is) a bunch of ‘hooey’ as far as keeping score, but for us running our business it’s an important

measure. What we do internally is what’s important, not if we get a ‘star’ on our shoe. This is one area if the

company wants to improve, we need to be a lot more consistent and define that criterion much more closely.

We routinely measured ourselves before the company did this. We gauge ourselves monthly on this one. We

ignore the BSC measure for our purposes, and use our own.” [1: 128-135]

“(Safety is a) hot button. The BSC uses a totally ludicrous measure, but the concept is great. I have written

four memos on this subject. I ran two plants before this. I have 100 technicians, and if those 100 have more

than one accident in a year, I’m in the red. Ridiculous!” [6: 109-111]

30

The data provide consistent evidence of causal paths connecting Ineffective management control, Ineffective

motivation, and Conflict/tension, which support the “ineffective” form of research question 2.

Other Findings

Strategy Alignment – Ineffective Management control or Ineffective Communication or

Ineffective Motivation – Positive Outcomes

The study found several unexpected causal relations and associations. Upon reflection, however, it is not

surprising that complaints about Inappropriate benchmarks are causes of recommendations to Modify measures or

BSC. Clearly, distributors, who have economic stakes in both their business’ success and contract renewal,

want relevant measures and attainable goals for DBSC Key factors. For example,

“Is the x% (benchmark percentage of technician hours used for training) appropriate? Hard to say. Probably

now, that would be a low number given (that)…the company will completely obsolete its own product line

soon. The need for training is much greater today than it has been in the past. Some companies will use

training dollars (rather than percentage of training hours). They are at like 5% (of revenues), which is much

22

higher than us. This raises a question in our minds. Do we do enough? We are concerned if we are reinvesting

enough in our employees.” [1: 183-190]

Additionally, the most numerous, consistent evidence (62 associations shown in dotted lines on the right

side of figure 4) shows that Key factors are associated with Inaccurate/subjective measures, Not understandable messages,

Inappropriate benchmarks, and Costly to measure. Distributors are frustrated when they perceive ineffective

implementation of DBSC factors that they believe are key to their business success and contract renewal.

Typical comments, for example involving the DBSC measure of training for salaried employees, include:

“(Training of salaried employees is) as critical (as for technicians) but harder to measure. We have to use some

guessing, because they are not paid hourly. Also, what’s training? Clearly going to a class during the workday,

but what about going after work? What percent of the total salaried hours is that?” [5: 155-160]

“For salaried people, it’s harder. We have to look at expense reports, and it’s a horrendous process. When you

bring this data collection problem to the company, they say we can’t do that either. They don’t even do it, and

they aren’t sure of the credibility of their number. From feedback from other distributors, they are just taking a

stab at it. We actually compile the numbers, but others are getting green scores for just a guess. We’re yellow

or red, and it’s a real number. The cost of the time isn’t worth it. But, it’s the right idea and the right thing to

do.” [1: 175-183]

Distributors’ frustrations were obvious when they realized that the DBSC was attempting to measure and

communicate important success factors, but that it was doing so ineffectively.

“We don’t grow much, so we need to find ways to expand. That’s all they pushed here (in contract renewal).

At another distributor, all they pushed on was customer satisfaction. Some areas if we (both) know we’re doing

a bad job and were red, they don’t seem to care…. Great tool but I’m not sure we are using it the way it

should be used” [8: 175-181]. “This is something we all should pay more attention to. We haven’t done as well

as we should have, but the goal means nothing to me because I’m so far away from it” [5: 122-125].

While the study did not anticipate these (and other similar) associations, their discovery provides ample

additional evidence of opportunities to improve the control and communication of strategy with the DBSC.

The study found relatively few instances of associations between Conflict/Tension and Positive Outcomes, which

may reflect both the relative newness of the DBSC and the top-down, one-way dialogue prevalent in the

company.

Summary of Results

The BSC is an innovative strategy communication and management control development. However, as

with all innovations, establishing its validity takes time, objective evidence, and careful analysis. There is

always the danger that promotional “hype” will promise more than a technique can deliver, which could lead

to disappointment, skepticism, and failure to recognize significant benefits, even if they are not as grand as

advertised. Kaplan and Norton [1996, 2000] bill the BSC as a complete, reliable strategic guide. It perhaps will

prove to be just that. However, there is limited objective evidence presented in support of this proposition.

23

For example, Ittner et al. [2000] do not find compelling evidence that a large bank’s BSC promoted increased

strategic awareness. More empirical evidence will be useful, because most of the BSC literature is either

normative prescription or uncritical reports of BSC “successes.” We believe this study provides a significant

contribution to the literature, of interest to both academics and managers.

The present study uses a method of analysis that moves management accounting field research in the

direction of more generalizability and internal validity than is apparent in most descriptive field research in the

area. While this qualitative approach can never achieve the external validity of statistical analysis of archival

data, perhaps it can aid researchers (and their critics) who seek to increase the objectivity and reliability of

field-study analysis.

Our findings are that, in at least one corporate setting, the BSC does present significant opportunities to

develop, communicate, and implement strategy – just as Kaplan and Norton aver. We find evidence that

managers respond positively to BSC measures by reorganizing their resources and activities, in some cases

dramatically, to improve their performance on those measures. More significantly, they believe that improving

their BSC performance is improving their business efficiency and profitability. Managers react favorably to

the BSC and heed its messages when:

• BSC elements are measured effectively, aligned with strategy, and reliable guides for changes,

modifications, and improvements

• The BSC is a comprehensive measure of performance that reflects the needs of effective management

• The BSC factors are seen to be causally linked to each other and tied to meaningful rewards

• BSC benchmarks are appropriate for evaluation and useful for guiding changes

• Relative BSC performance is a guide for improvement

However, problems of designing and implementing the BSC may be no different from those associated

with any major change in performance-measurement systems. The following factors were found to negatively

affect perceptions of the BSC and cause significant conflict and tension between the company and its

distributors.

• Measures are inaccurate or subjective

• Communication about the BSC is one-way (i.e., top-down and not participative)

• Benchmarks are inappropriate but used for evaluation

Though some of these adverse findings are associated with recommendations for improvement, most are

found to be causes of unproductive conflict and tension or a general atmosphere of ineffectiveness. For

example, the study found many examples of key factors that were ineffectively implemented in the company’s

BSC. Left uncorrected, these negatives could result in deteriorated relations, increasing “imbalance” in the

BSC as focus shifts to more objective, short-term financial measures [Ittner et al., 2000], and forfeiting the

24

communication and management control benefits of the BSC. For example, we can speculate that we did not

observe sufficient relations between Positive outcomes and Conflict/Tension because there is little dialogue (or

dialectical process) between the company and its distributors – we found only 6 associations. In this case it

appears that conflict simmers and rarely results in a positive outcome.

On the brighter side, the previous bullet points represent value-added and non-value-added BSC

activities. To successfully design, implement and use the BSC, organizations should enhance the former,

positive factors and eliminate or correct the latter, negative factors. It may be worth noting that the total

number of consistent links on the “ineffective” side of the model in figure 4 far outweighs those on the

“effective” side (154 to 59). Thus, the predominance of negative perceptions reflects many opportunities to

improve both communication and control of strategy. It seems likely that this ineffectiveness could be

resolved and the negative outcomes of unnecessary conflict and tension could be avoided at relatively low

cost (though it may require significant changes in attitudes). Possible solutions could be as simple as

improved dialogue between the company and its distributors regarding important but ineffectively measured

or poorly understood DBSC factors [e.g., Lindquist, 1995].

Limitations and Future Research

Even though many of this company’s managers and distributors apparently use the DBSC as a valid

representation of their business, we recognize that their reported perceptions may not be valid

representations of their actions. To our knowledge, however, there has been no rigorous, statistical test of the

claim that the BSC is, in fact, a causal model, which is the focus of our ongoing research.

Preliminary analysis of the statistical properties of the host company’s DBSC confirms many expected

causal relations and in particular shows the importance of modeling time lags between changes in investments

in internal processes, customer value, and financial performance. Consistent with distributors’ beliefs, we

have found that “upstream” changes may not result in tangible financial improvements for over a year.

“You will see very little change from quarter to quarter. Last quarter only one measure changed” [9: 121-124].

“I expect a three to five-year lag to see a significant impact of market penetration investments. I’m spending a

gazillion dollars on it, but returns will be in about five years. We’ll see some short-term returns soon, but the

big returns are five years down the road” [2: 148-151]. “My gut feeling is that it took two to three years to

reorganize and retrain, and four or five years later it started to pay off. I expect a quicker response now from

improving the fill rate and one-hour diagnosis” [6: 205-207]. I would think about half a year to a year for the

parts fill rate. Do well, and your reputation becomes known and you’ll see some effect in the financials. It’s a

matter of customer awareness that we’re doing something different here that will bring repeat business” [3:130-

133].

“People are very sensitive. They let us know if we are not living up to expectations. Some of our

customers are looking elsewhere to get parts because of stocking problems. Customers will react in a six-month

window” [1: 217-223]

25

Practical difficulties that are encountered in any statistical test of a BSC include:

• Changes in BSC measures and links as systems evolve to meet changing conditions

• Changes in organizations, markets, and personnel that may affect BSC structure and links

• Long lead times before effects are seen in lagging measures of performance

• No effects or negative results that may be attributed to “bad design” or “bad implementation” rather

than to the concept of the BSC as a causal model

• Desirable effects or positive results that may be caused by other, related (but omitted) factors, but are

attributed to the BSC

Making progress on controlling these factors offers opportunities for significant contributions to our

understanding of strategy communication, performance measurement, and evaluation characteristics of the

BSC.

Epilogue

Since the data collection for this project in mid-1999, the DBSC has undergone significant changes. The

company has added new measures and deleted some of the original ones; adjusted weightings; and

reconfigured categories. The company did not change benchmark targets of the retained measures. The most

notable changes came into effect at the end of 1999 when DBSC managers trimmed it from 30 to 20

measures. One major adjustment was continuing de-emphasis of the Learning and Growth category – it is

now eliminated from the DBSC, but the measures continue to be compiled on an annual basis. This

important area of performance was a casualty of unreliable measurement – but perhaps presents an

opportunity for improving the DBSC. Another change is enhancement of measures of new market share,

largely at the request of distributors facing significant growth opportunities in the new markets. In this case,