Newsletter Issue No. 8 suMMer 2013

Issue No. 9 wINter 2013/2014

It has been a hugely busy start to the academic year

2013/14 for staff and students alike. Our Anthrosociety

has held a successful debate, hosting Dr Jo Cook and Dr

Lucio Vinicius on the topic of Piece of Mind. Staff put the

nishing touches on the Research Excellence Framework

submission due this November and began to discuss the

directions which research and teaching will take in the

Department over the next seven years. With the arrivals

of the new President & Provost, Professor Michael Arthur,

and the new Dean of the Social and Historical Sciences

(SHS), Professor Mary Fulbrook, the College is abuzz

with debate about the vision for UCL reaching forward

into the 2020s.

The past academic year has seen a consolidation of all of

our activities in the Department, with a now fully staffed

administration, thanks to the arrival in April of Jolanta

Skorecka as Undergraduate Administrator. A successful

Internal Teaching Quality Audit delivered much praise

for our staff and students and the wonderful creative,

productive and supportive atmosphere that we enjoy

in our department. The committee’s advice on how to

tighten some of our internal processes and committee

structure were implemented straight away and staff and

students should see the benet already this year in a

smoother ow of information up and down the spine of

our command structure. As always, however, changes

induced by UCL’s vast engine room are keeping us on

our toes and promise to make this academic year far

from boring.

The rst year BSc students are looking forward again to

their eld trip in February, and we are busy with planning

the implementation of a 2nd year eld trip, directed to

life skills, as requested by our students. We are awaiting

the rst running of the new compulsory 2nd year course,

‘Being Human’, on which all staff will teach following a

new teaching format inspired by the Oxbridge tutorial

structure.

Sadly we had to remove the staff book covers from the

main stairwell, but thanks to Paul Carter-Bowman in

the ofce, our master’s student Shweta Barupal, and

recently completed PhD student Aaron Parkhurst, most

of the covers have already been rehung beautifully on the

ground oor and in the staff common room, with further

hangings planned on the 2nd oor near the Seminar

room. Towards the end of this academic year we have

been promised the start of a huge renovation project for

our walls, carpets and common rooms, and I am sure

that this will be welcome news for us all.

Perhaps the greatest credit to the excellent teaching and

the huge energy invested by our staff in the care and

attention to advancing student learning is the repeat of

the stellar performance of our 3rd year students, which

saw almost half of our students leaving the College

in June with a First Class Honours degree, two of our

students being put forward to the Dean’s list, and the

remaining students being awarded good and very good

Upper Second Class Honours degree results. Four of our

students have left us with PhD studentships at the LSE

and Cambridge, and we are very proud to have been able

to fully fund a fth student with an ESRC studentship to

stay with us. Three of our PhD students won competitive

postdoctoral research grants and are supported for 2

and 3 year periods by the ESRC, Leverhulme Trust and

Marie Curie. Two of our staff are shortlisted for ERC

grants, results pending. And so we are rejoicing in the

success of our students and staff and are looking forward

to the new academic year with condence and a desire

to match or improve upon these results.

I wish you all a very happy and productive year.

Professor Susanne Kuechler, Head of Department

Welcome

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

3

INSIDE THIS ISSUE

4

6

8

12

13

14

16

22

24

25

26

27

ANTHROPOLITAN is published by UCL Anthropology © 2013

CONTRIBUTORS

Aarthi Ajit, Nienke Alberts, Alexandra Antohin, Carol Balthazar, Joe Calabrese, Paul Carter-Bowman, Nik Chaudhary, Mark Dyble,

Susanne Kuechler, Charlotte Loris-Rodiono, Hannah Luck , Andrea Migliano, Abigail Page, Christopher Pinney, Alice Rudge,

Chris Russell, Deniz Salali, Daniel Smith, Jed Stevenson, Poppy Walter

EDITORS

Allen Abramson, Paul Carter-Bowman, Lucio Vinicius, Man Yang

SPECIAL THEME: THE INFORMANT’S VIEW OF THE ETHNOGRAPHER

Being a Spy or a Black Shaman in Southern Siberia: Fieldwork Among the Shors, by Charlotte Loris-Rodionoff

Ethnography as Devotion - An insider backstory in the heart of Ethiopia, by Alexandra Antohin

SPECIAL FEATURE

Now Delhi is Not Far, by Christopher Pinney

CURRENT STUDENTS

Stigmatising HIV/AIDS in Malawi, by Hannah Luck

FROM OUR ALUMNI

God Bless the Tools, by Aarthi Ajit

STAFF PROFILE

An Interview with Joe Calabrese

RESEARCH

Hunter-Gatherer Resilience Project

Snifng out a mate, by Nienke Alberts

EVENTS

A beginning for LabUK, by Carol Balthazar

Piece of Mind: A Dabate on the Path to Happiness, by Poppy Walter

DEPARTMENT NEWS

New Appointments and Recently Awarded PhDs

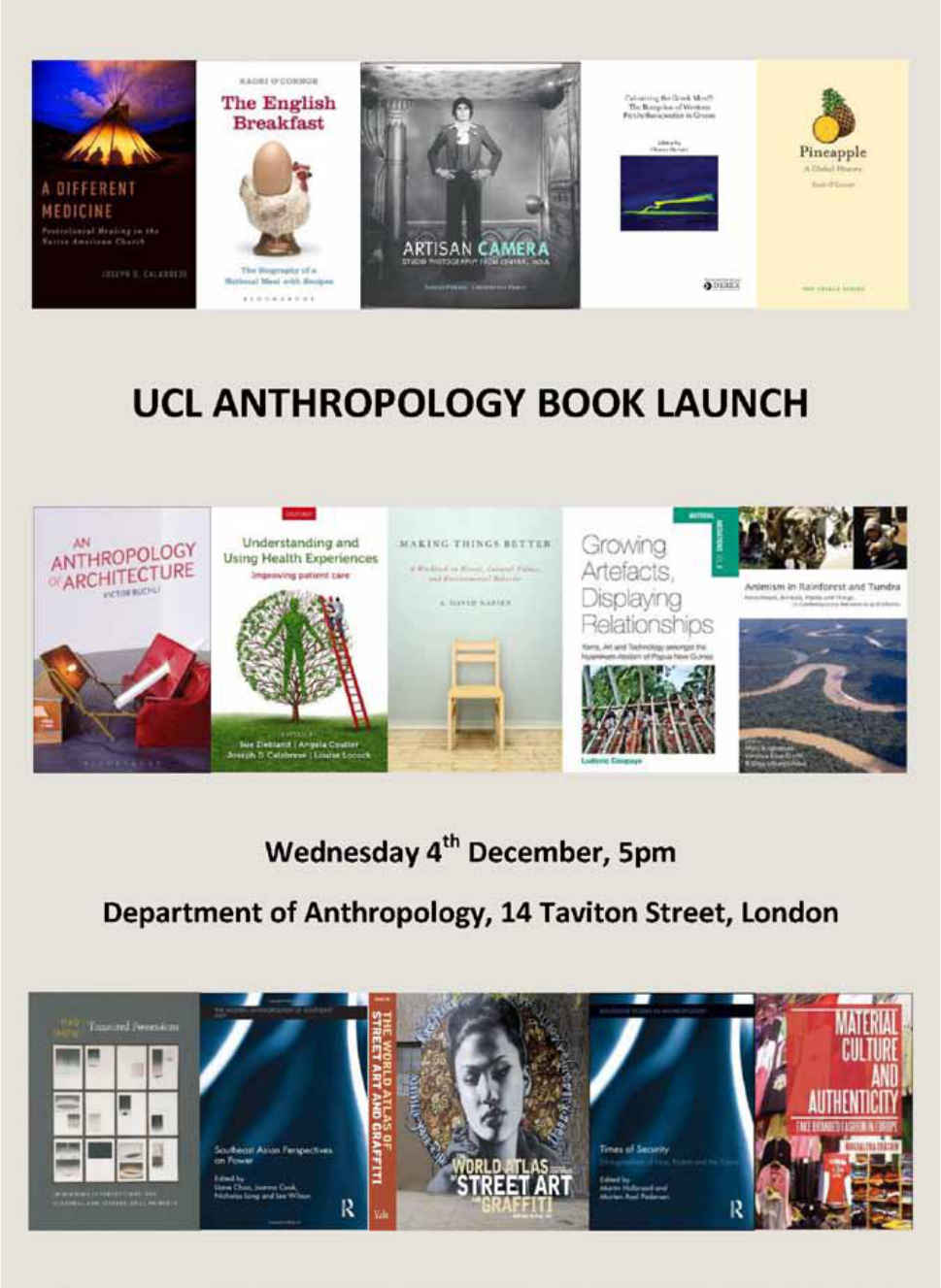

New Books by Staff

4

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

SPECIAL THEME: THE INFORMANT’S VIEW OF THE ETHNOGRAPHER

This SMS – where ‘her’ is ‘me’ - was sent

to my hosts a few weeks after my arrival

in Gornaya Shorya, a mountainous area

located Kemerovo region in the north

of the Altai-Saian, 3,700 km south of

Moscow. I aimed to study shamanism

among the Shors, a small Turkic people,

who live in mountains covered with

taiga, a dense evergreen forest. But as

soon as I arrived after a three-day long

train trip, Petr condently announced

that: “there are no shamans left among

the Shors”. Surprisingly, he sent me an

email about a month earlier offering to

introduce me to a shamaness, Anna,

with whom I could work. I was puzzled

to hear that there were actually no

shamans left in the region. However,

I quickly understood that Petr did not

mean that there were no shamans left

at all among the Shors, rather that

there were no genuine shamans left:

only “incomplete”, “unauthentic”, “non-

traditional” shamans live in Shorya. This

absence of “genuine” shamans strongly

contrasted with the omnipresence of

shamans and shamanism in jokes and

talks.

Nonetheless, people did not speak

‘seriously’ about shamanism with me;

not because of the so-called absence

of shamans, but because people did not

see why they should speak about it with

me - a foreign anthropologist. People

started to speak to me about shamanism

after my place in this communicational

situation changed: I had to be a part

of this shamanic discourse for me to

be told (and taught) about it (Favret-

Saada 1980). The situation shifted after

two shamanesses decided that I was

not a scientist to keep away from their

esoteric knowledge and practices, but

rather a potential initiate. Given that I

“still did not choose any religion”, they

resolved to “teach me shamanism”.

They thus had to unveil things shamanic.

However, my position of initiate was

unstable: after two days spent with

the shamanesses, they sent my hosts

the SMS copied above. I was now “a

person who serves the dark forces”: a

black shaman. Yet I was not ‘just’ a black

shaman. A few hours after the SMS was

sent, the shamaness Anna called my

hosts, warning them against me, saying

that I was a black shaman and a spy.

This double accusation was followed

by immediate reactions: the doors of

the community closed one after the

other on me, and, apart from my hosts,

no one would speak to me anymore. I

no longer enjoyed the “comfortable”

position of the foreign anthropologist,

but I was in the uncomfortable one of a

black shaman/spy.

Indeed, after the accusation spread

in the city, one thing was certain: I

was working with the dark forces, I

Being a Spy or a Black

Shaman in Southern

Siberia: Fieldwork

Among the Shors

Charlotte Loris-Rodionoff

MPhil/PhD in Social and Cultural

Anthropology

“Remember the most important thing: shamanism is not

something exotic, and it brought the death of civilisations!

We watched her. You sent us a person who serves the

dark forces. We understand their interests. Do not try to

understand – do not go in this sphere if your life is dear to

you! The dark forces do not know how to have pity or how

to pardon. Stay in your own scientic sphere.”

“A few hours after the SMS

was sent, the shamaness Anna

called my hosts, warning them

against me, saying that I was a

black shaman and a spy.”

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

5

was ‘not quite an enemy’. Everybody

was worried about the possibility of

a bad omen, and/or of problems with

the local police, or worse, with the

FSB (Federal Security Service). Even

Makar, a convinced atheist, was not

certain that I was harmless: he kept

mentioning, sarcastically laughing, that

I must be a very good spy, since I did

not look like one. This suspicion was

partly grounded on my fuzzy status,

since there are practically no foreigners

in Shorya, and my identity was unclear,

for I introduced myself as French, but

I also revealed my Russian descent

as it explained my knowledge of the

language. But the accusation was also

cosmological: I was a black shaman. I

found myself in a reverse situation to

Favret-Saada (1980). Whilst she became

an intimate friend and an assistant

of a magician in the French Bocage, I

became an intimate enemy of the Shor

shamanesses of whom I was a potential

initiate.

This tricky position yet gave me a better

understanding of contemporary Shor

society: rst, it made me realise that

shamanism and politics are intimately

intertwined, and that there is a troubling

“isomorphism of form” between these

two spheres in Shorya (Pedersen 2011).

Second, it gave me a better insight into

Shor social relations. The Janus-like

figure of the black shaman/spy made

clear that suspicion of spies (politics)

had a shamanic dimension. And, indeed,

any outsider, political opponent, rival

shaman, or Shor with whom another

Shor is in conict, is referred to as a

black shaman; while any foreigner,

anyone having a fuzzy status, is called

a spy.

In short, this experience revealed that

even when perceived ‘negatively’ and

suspiciously by one’s informants, one

can still do fruitful eldwork! Although I

was seen as a suspicious person, rather

than an anthropologist, and I could not

establish relations other than those

based on mistrust and deceit with my

informants, this eldwork experience

gave me an intimate access to the Shor

society.

References

Favret-Saada, Jeanne. 1980. Deadly

Words: Witchcraft in the Bocage.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Pedersen, Morten Axel. 2011. Not

Quite Shamans: Spirit Worlds and

Political Life in Northern Mongolia.

London: Cornell University Press.

SPECIAL THEME: THE INFORMANT’S VIEW OF THE ETHNOGRAPHER

Left: Map showing the location of Kemerovo

region in the Russian Federation (en.wikinews.

org)

6

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

SPECIAL THEME: THE INFORMANT’S VIEW OF THE ETHNOGRAPHER

Having imagined my home for the

next year and a half on Google Maps,

my doctoral fieldsite was a location

I could not nd. Gishen Debre Kirbe

was a flat-topped mountain, its

plateau distinguishable as resembling

the contours of a cross, where in the

church of St. Mary my grandmother

was baptised in 1934. A difcult journey

on mule and winding dirt roads that

took nearly a month to complete,

brought mother and child to this

remote place to full a vow. This act

broke the misfortune of many failed

pregnancies by giving the new-born to

Gishen Mariam, more specically to the

tabot (ark and altar) of this church. The

intrigue of not nding its coordinates

on a map and the draw of the personal

connection spurred my interest to start

with Gishen.

Rather strategically, I also recognised

that this personal story would be

useful with the Orthodox Christian

communities I planned to work with.

Whatever privilege the ‘’insider’’

anthropologist role was expected to

afford me, I aimed to exercise a certain

versatility of shifting positions due to

my claims to roots (Narayan 1993). My

“way in’’ would be as a participant in

an intergenerational rite of promise,

representing the newest link in this chain

by honouring the memory of Gishen,

how “Mariam listened and protected’’.

This logic would translate well, I

anticipated, giving the ethnographer

context. And, sure enough, when

this backstory disappeared, I became

a foreigner, causing individuals to be

genuinely mystified at my extended

presence at Gishen.

To study pilgrimage (lit. ‘spiritual

journey’ in Amharic) required

committing oneself to a sort of mission.

Surely, this anthropology business

was a guise. In my case, a scholastic

curiosity about the devotional customs

of Ethiopian Orthodox Christians was

interpreted by many as an inner, spiritual

motivation to be closer to the religious

heritage of my generations past. Both

my biographical details and Christian

personhood were constantly recast

in an interactive exchange between

the ethnographer and her informants

(Reitsikas 2008). It was accurate to

call me an Orthodox Christian, one

knowledgeable and intimately familiar

with its traditions but not a confessing

one, as I had never taken communion.

Fears of proselytism in the way Blanes

(2004) discusses in his strategising of

an ‘’unnished agnosticism” were not a

concern, though I did engage in a similar

open-ended possibility of the deeper

Christian I might become as a result of

this project. My ethnographic activities,

for many of my interlocutors, were

about stretching my belief.

Several weeks before thousands of

travellers would head an additional

300 km north to the town of Lalibela,

I decided to visit this famed holy site

early. This experience had all the

A priest accepts a donation for the sake of St. Mary: in the background, a trail of buses parked at Gishen.

Ethnography as Devotion

An insider backstory in the

heart of Ethiopia

Alexandra Antohin

PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

7

SPECIAL THEME: THE INFORMANT’S VIEW OF THE ETHNOGRAPHER

hallmarks of a typical long-distance

journey in Ethiopia, particularly the

combination of a reckless driver and

fatal or near-fatal accidents along the

road. Despite these known factors, the

trip was an absolute nightmare, directly

life-threatening and inauspicious on

both legs of the journey. One reaction

to these events by my cousin was not

at all surprised that our entrance was

“rejected’’ as he put it. ‘’One doesn’t

just go to a holy place in a hurry’’ he

said. To “get permission’’ is an active,

dialogic negotiation that is based on

reinforcing ties with God and by giving

offerings to the church. My lack of

subscribing to a regime made glaring

the importance of making promises to

reconrm links, dening belief, through

devotional acts, as “the quality of a

relationship, that of keeping the faith,

having trust” (Ruel 1982: 22).

Brushes with death on pilgrimage can

also indicate signs of spiritual proximity

and potency. On one occasion while

descending Gishen, a large bus tipped

over to the side of a road no more

than four meters wide. Fisseha, a

fellow pilgrim, prompted me to take

photographs of the accident. Horried

and a bit stern in my response, I

refused, and kept silent my opinion that

this act gloried tragedy and showed

a flippant reaction to the fragility of

life. He looked at me blankly, not

comprehending my indignation. “But

it’s a miracle. They didn’t die. This is

proof of God’s power and love. That’s

what we are celebrating.’’ This thin line

between tragedies and miracles, rather

than demonstrating a much-cited

emphasis on ‘’god-fearing’’ by Ethiopian

Orthodox Christians, in fact stands for

a certain relishing of the unknown. It is

a type of communication that Orthodox

Christian direct to what they label

as ‘’the sacred’’, as ‘’a way of coping

with certain epistemological problems

– maybe necessary ones?” (Bateson

& Bateson 1988: 86). Belief, rather

than a statement of truths we know,

represents the truths we don’t. It is

this confrontation that is being sought

after and the work that implicates

individuals to realise this encountering

between this and the other world. As

it was stated to me by one pilgrim to

Gishen, “the journey to the sacred

place is always trying and exceedingly

long. The return to the world is short

and easy.’’

Bateson, Gregory, and Mary Catherine

Bateson. Angels Fear: Towards an

Epistemology of the Sacred. London:

Rider Books, 1988.

Blanes, Ruy Llera. “The Atheist

Anthropologist: Believers and Non-

believers in Anthropological Fieldwork.”

Social Anthropology 14, no. 2 (June 2006):

223–234.

Narayan, Kirin. “How Native Is a

‘Native’ Anthropologist?” American

Anthropologist 95, no. 3 (September 1,

1993): 671– 686.

Retsikas, Kostas. “Knowledge from

the Body: Fieldwork, Power, and

the Acquisition of a New Self.” In

Knowing How to Know: Fieldwork and

the Ethnographic Present, edited by

Halstead, Narmala and Hirsch, Eric and

Okely, Judith, (eds.), 110–129. Oxford:

Berghahn Books, 2008.

Ruel, Malcolm. “Christians as Believers.”

In Religious Organization and Religious

Experience, edited by J. Davis. London:

Academic Press, 1982.

Top left: Pilgrims descending after the

conclusion of the feast day.

Top right: Approaching a monk outside his cell.

Left: Celebration of liturgy and the offerings to

church.

8

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

My most recent trip to India (late

August through to end September 2013)

was chiey to organise a photographic

exhibition in a New Delhi art gallery,

part of Delhi Photo Festival. The

exhibition was a selection of prints

made from negatives dating from the

late 1970s and early 1980s salvaged

from a small-town studio’s warehouse

in central India.

The printing was done in London and

I took the images to the framers when

I arrived in Delhi before then heading

south by train to Madhya Pradesh for

a few weeks in the town where I’ve

worked intermittently since 1982. The

exhibition was due to open on 25th

September and I was returning to

Delhi a few days before to set things

up. Suresh Punjabi, the small-town

photographer would come up very

early on the day of the opening with his

family and stay one night in the New

Delhi bungalow of the local MP before

returning to the continuing work in the

studio.

Two days before I returned to Delhi

the local media fervour started. Suresh

arranged a series of group interviews

with local reporters and video

journalists, his planned news conference

having been cancelled through lack of a

suitable space. Prior to this Suresh had

been rather puzzled about the reason

for the exhibition, assuming that his

workaday portraits would appeal only

to “foreigners” who would be struck by

the “strangeness” of Madhya Pradesh

life. He also engaged in his own acts

of visual translation, deciding that the

invitation to the opening which had been

prepared by the gallery (Art Heritage),

while excellent, was inappropriate for

the aesthetics of a small-town. The

gallery had sent 50 copies for Suresh

to distribute locally but he decided to

print 300 of his self-designed invitation

Now Delhi is Not Far

Christopher Pinney

Professor of Anthropology and Visual Culture

“Prior to this Suresh had been

rather puzzled about the reason

for the exhibition, assuming that

his workaday portraits would

appeal only to ‘foreigners’

who would be struck by the

‘strangeness’ of Madhya

Pradesh life.”

SPECIAL FEATURE

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

9

because the Delhi-produced one was

zyada hai (“too high”, ie “too high

class”).

In the numerous interviews in the

days before I left it became clear how

important key facts were in defining

what kind of event this should be:

the location of the gallery (its central

position in New Delhi being of great

importance), the fact that all the

images in the show were by Suresh

(they were not mixed with and hence

diluted by the work of others), that

the name of Studio Suhag would be

outside the gallery, and that important

photographers would be present

at the opening. Having established

these key elements of the narrative

with reporters from Nai Duniya and

Dainik Bhaskar (the two major Hindi

newspapers), these elements were

then formalised in a press release

which found its way into stories used by

numerous other local Hindi publications

with much smaller circulations. We also

did numerous video interviews for local

cable networks in which I stressed,

with Suresh’s encouragement, the

aesthetic power of his images since he

SPECIAL FEATURE

10

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

SPECIAL FEATURE

had started to understand that it wasn’t

only “foreigners” who would nd them

striking and interesting. Suresh also

decided that he would send one of his

videographers, Ankit, to record the

whole event since he wanted the pura

clip (“whole clip”) of the event.

I had a midnight train to Delhi and an

astonishing late monsoon storm raged

all day. Torrential, lashing rain was

accompanied by terrifying thunder.

My train, which had departed twelve

hours earlier from Mumbai was three

minutes late. The day of the opening

arrived and the show looked great:

Suresh and his family were nally faced

with the translation of his studio work

from several decades ago into the white

cube of Art Heritage in the Kala Triveni

Sangam arts complex. Now Delhi was

not far (Ab Dilli Dur Nahin was the title of

a famous 1950s Raj Kapoor movie about

migration to the city). My anxieties

about the collision of two very different

worlds faded as Suresh talked amiably

with the celebrated performance artist

Pushpamala N, the World Press Photo

award winner Pablo Bartholomew,

and the renowned photographer Ram

Rahman who “released” the book

which accompanied the exhibition

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

11

SPECIAL FEATURE

(Artisan Camera: Studio Photography from

Central India). We were also graced by

the presence of Ebrahim Alkazi who has

probably had more impact on visual arts

and drama in India in the last fty years

than anyone else. After the opening I

gave a lecture in the adjacent open-air

auditorium. It was raining heavily in

most parts of Delhi but somehow we

were saved from the deluge.

Suresh is no longer simply a small-town

photographer but has gained a foothold

in the Indian Artworld and been written

about in many of the national daily

newspapers. Google “Studio Suhag”

to see his responses on Facebook

(mediated by his English-speaking son

Pratik). A new circuit of representation

and visibility has been created in part

through anthropological participant

transformation. The show will go to

Chennai in a few months and then,

funds permitting, I’ll hire a shop front in

that town in Madhya Pradesh where we

will create its rst pop-up art gallery.

12

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

CURRENT STUDENTS

In 2010, after my rst year of studying

Social Anthropology at the University

of Manchester, I travelled to Malawi to

work with a community development

charity in feeding centres for HIV

orphans in the Southern region. During

my time in Malawi, I was able to form

close friendships with a group of 18-20

year old men involved in the local

Scout group. I was able to talk frankly

with them about issues such as their

expectations of girlfriends and wives,

church and their religious beliefs. Our

conversations were mainly centred on

the Malawian men mocking me and

proclaiming how awful it would be to be

married to a woman as disobedient as

me (a sentiment I can’t disagree with).

After returning from Malawi, I became

increasingly interested in the role

Pentecostal churches play in the HIV

epidemic across Southern Africa with

specic focus on how religious teachings

on sexual purity and divine retribution

have contributed to the stigmatisation

of people living with HIV/AIDS. I

looked at how the stigmatisation of

seropositive people has directly affected

how likely people are to get tested for

HIV. Additionally, I wanted to look into

the role of masculinity constructions in

the spread of HIV whilst looking at the

efforts of Assembly of God churches in

Zambia to create a ‘biblical masculinity’

in response to the epidemic. My time in

Malawi was the inspiration behind my

work throughout my undergraduate

studies and continues to be a source of

interest for me today.

Stigmatising HIV/

AIDS in Malawi

Hannah Luck

MSc Medical AnthropologySc

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

13

Surely everyone has a favourite festival

or holiday. There are so many locally

and internationally, it’s near impossible

not to have at least one. One of my

favourite festivals is known as Ayudha

puja, part of the nine to ten-day series

of festivals across India generally

acknowledged as Dasara. I remember

Ayudha puja also as Saraswati puja

from my childhood, where we would

happily give up our schoolbooks for

one entire day, in order to make a

worthy assemblage of objects for the

puja or ritual, and subsequent blessing

by Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of

wisdom, learning and the arts. We were

allowed to bunk off school as well –

which is why school-going children are

particularly fond of this festival. Simply

put, Ayudha puja is held to give thanks

for the divine force that keeps safe and

functional the tools and implements

that enable our professional lives to

run smoothly. Traditionally, the items

put up for blessing are books, tools,

machines, weapons, motorised vehicles,

even musical instruments. But it’s not

surprising to hear of laptops, juice

blenders and other more contemporary

tools being included in the puja.

This year Ayudha puja was held on

October the 13th. A text message I

received early morning read: “Happy

Ayudha Puja – to all material things!” I

happened to be vacationing with friends

on the banks of the Krishna Raja Sagara

dam/lake, near Mysore, India, and the

guesthouse owner mentioned that

his cook’s family would be doing their

version of Ayudha puja around noon.

Would we like to see it?

The ritual begins with us removing our

shoes and approaching an arrangement

of polished knives, several agricultural

implements, power tools and a ladder,

which have been decorated with jasmine

owers and chrysanthemums, mostly

yellow in colour, as well as fruits and

a halved coconut. A suitably decorated

bicycle rests to the side. The puja is

conducted by the cook’s adult son,

first by smearing each of the objects

individually with turmeric, vermillion

and sandalwood paste, and then by

lighting a piece of camphor, which in

turn is used to light a few incense sticks.

The incense envelops the objects; no

words are uttered. A chicken is silently

sacriced at the very end of the ritual.

In less than ten minutes it is over, and

the objects are left in peace for the rest

of the day.

What is interesting is that the cook’s

family are Christian, not Hindu, but have

been celebrating Ayudha puja as a part

of their annual festival repertoire, just

as their ancestors (prior to conversion

to Christianity) would have done. This

would explain why there were no

pictures of Hindu goddesses on the dais,

a common occurrence elsewhere. I like

this festival because it seems to allow

for a veneration of gods and objects in a

religious and/or ritualistic way – a more

inclusive approach for Indians of diverse

religions to say “thanks for the tools”.

Aarthi Ajit has a MA in Material and Visual

Culture (2012), from the Department of

Anthropology, UCL. She is pursuing a PhD

in Ethnology at Université Paris Ouest

Nanterre La Défense and can be reached

at: a.ajit.11@alumni.ucl.ac.uk.

FROM OUR ALUMNI

God Bless the Tools

Aarthi Ajit

MA Material and Visual Culture (2012)

Below: Household tools being blessed on the

occasion of Ayudha Puja

14

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

STAFF PROFILE

What are you currently doing

research-wise?

At this point, I am pondering my dual

identity as an anthropologist and

practitioner psychologist, exploring

various concepts and approaches at

the interface between anthropology

and clinical disciplines. This dual

identity leads me to practice a different

mode of ethnography and a different

mode of clinical practice. In my

current fieldwork in the Kingdom of

Bhutan, I am again employing a clinical

ethnography approach, embedding

myself as a member of the clinical team

at the country’s main referral hospital

during the last three summers. This has

stimulated reection on the best uses of

clinical ethnography, both for improving

healthcare and for the development of

anthropological understanding.

I’ve just published a monograph on

my earlier work with the Navajos,

called A Different Medicine: Postcolonial

Healing in the Native American Church,

and I continue to explore concepts

developed in that work, including

culturally embedded therapeutic

emplotment, clinical paradigm clash,

the dynamics of postcolonial healing,

the multiplicity of the normal, and an

alternative semiotic/reexive paradigm

of psychopharmacology. I also recently

co-edited a book called Understanding

and Using Experiences of Health and

Illness, with colleagues from Oxford,

which reviews various methods used to

study health experiences.

I am interested in clarifying the best

uses of modern medical/psychiatric

approaches and the best uses of

traditional ritual-based approaches. In

A Different Medicine, I argue that ritual

interventions are the most appropriate

and clinically useful approaches to

alcoholism and many other behavioural

disorders among the Navajos. For many

problems, modern medical approaches

remain the most useful approaches.

However, we need to “decolonize”

clinical knowledge, becoming aware

of the European and Euro-American

cultural values embedded in it like

individualism, materialist focus on

biological reductionism, capitalist focus

on healthcare as a commodity rather

than a basic human right.

What current projects are your students

involved in at the moment?

I really enjoy working with students and

have had so many wonderful students

at UCL, both anthropologists and

clinicians. Their projects encompass

studies of embodiment, traditional

medicine, psychotherapy, racial

categories as they impact clinical trials,

gender roles as they impact HIV testing,

medicalization of childbirth, trauma

and social reintegration of African child

soldiers, traditional hospitality and

hosting practices in Bhutan, and many

other fascinating topics.

What is next?

Bhutan is my main field site going

forward. I am studying the lives of

Bhutanese people with mental illness,

the effectiveness of modern psychiatric

treatments in this context, and the role

of ritual healing, traditional medicine,

and Buddhism. I am also trying to

support the medical system in Bhutan

through training and research that

informs policy and practice. They

are trying to establish a University of

Medical Sciences and I have been invited

to become a Visiting Lecturer (during

my breaks from UCL). I plan to develop

curricula in Medical Anthropology and

mental health.

How did you become an anthropologist?

Tell us a bit about your career so far?

An Interview with

Joe Calabrese

Lecturer in Medical Anthropology, His research

focuses on the study of culture and mental health,

ritual healing, traditional medicines, therapeutic

narratives, postcolonial revitalization movements,

and comparative human development.

Joe (right) and Chief Psychiatrist of Bhutan

Chencho Dorji in Traditional Men’s Dress

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

15

STAFF PROFILE

It has been a long and twisty path.

During my undergraduate education,

which was in a School of Music, I became

interested in ethnomusicology. I had

connections to the Haitian community

in Chicago, where I grew up, and spent

a summer in Haiti, living with a Haitian

family and attending Vodou ceremonies

each weekend (I had been impressed

by recordings of the polyrhythmic

drumming of these rituals). This rst

experience of eldwork changed me in

many ways. For one thing, I observed

incredible poverty, which stimulated an

interest in postcolonial populations and

inequality. In addition, I had been raised

in a Catholic family and the prevailing

image of Vodou in Catholicism, and in

American society generally, was that it

was evil Devil worship. But I found the

people at Vodou temples to be normal

people going about the religion in which

they were raised, which, of course, was

very different from the religion in which

I was raised. I was welcomed and fed

(those “evil” Vodou sacrices end up as

a tasty chicken and rice dish). The men

shared their rum with me and the old

women tried their best to teach me the

complicated Vodou dances (at which I

utterly failed). I became fascinated by

the non-pathological spirit possessions

I observed, which drew me into

psychological anthropology and away

from ethnomusicology. I also became

sick in Haiti and was cured by a horrible

tasting leaf tea, which drew me into the

study of traditional medicines.

Soon after this, I became aware of a

Native American postcolonial healing

tradition that was under attack in

a Supreme Court case: the Native

American Church (NAC). Members

of this tradition use the psychoactive

peyote cactus as a sacred medicine.

As I got into eldwork on the NAC, I

completed an MA in Anthropology at

the University of Illinois and entered a

doctoral programme at the University

of Chicago. Chicago is known for its

interdisciplinary committees and I

entered the Committee on Human

Development, which allowed me to

be trained in both anthropology and

clinical psychology. My supervisor

was Ray Fogelson, who was a student

of Hallowell and Wallace and an

ethnographer of the Cherokee. One

of the co-founders of the Committee

on Human Development was Carl

Rogers, so my clinical training was

very humanistic with a strong dose

of cultural psychology (though I

also took medical courses such as

neuropsychopharmacology and

developmental biopsychology). I

completed two years of eldwork on

the NAC. In my Navajo fieldwork, I

combined anthropological immersion

in Navajo communities with a year-

long clinical placement at a Navajo

treatment program that incorporated

traditional healing rituals into the

treatment process in response to the

local demand for culturally appropriate

healthcare.

After Chicago, I went on to complete

my training in Clinical Psychology with

a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard

Medical School, during which I treated

adult psychiatric patients at the

Cambridge Hospital. I focused on mind/

body approaches, including hypnosis,

biofeedback, and mindfulness, though

I had supervision

from psychodynamic

and cognitive

orientations as well.

I then completed

the Medical

Anthropology

Research Fellowship

at Harvard,

w o r k i n g w i t h

Byron and Mary-Jo Good and Arthur

Kleinman. There I collaborated on

an ethnographic study of the Harvard

teaching hospitals that was published

in the book Shattering Cultures. After

a time as the first Cannon Fellow in

Patient Experiences and Health Policy

at Green Templeton College, Oxford,

which resulted in some publications on

health experiences in the UK, I settled

into my current position at UCL.

Are you only an anthropologist?

That’s a bit complicated. I see myself

primarily as an anthropologist ... and

I see this not as a profession but as a

basic orientation to life. I am also a

practicing clinician and I feel that this

clinical involvement makes me a better

anthropologist. It’s like one side of

my brain is an anthropologist and the

other half is a clinician. I continually

subject the anthropological half to

clinical critiques and the clinician

half to anthropological critiques. So

hopefully no idea goes unchallenged.

My basic philosophy is dialectical, so

I tend to believe that truth is a more

encompassing perspective getting

beyond the initial dichotomy. And I am

still a musician, currently obsessed with

the 24 string baroque lute (though I play

primarily for therapeutic purposes).

Below: A Vodou Ceremony in Haiti 1989

16

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

Hunting and gathering have been the

major occupations of humans since

homo sapiens emerged (200,000

years ago). Although it has been the

longest and most diverse bio-cultural

adaptation in humanity’s existence,

we know very little about the ways in

which hunter-gatherers have adapted

to pressures and maintained their

resilience. While the number of hunter-

gatherers that have disappeared is

unknown, the consequences of their

extinction are evident in humanity’s

current low genetic diversity, and in the

uneven distribution of languages, where

95% of the world’s languages are spoken

by only 6% of the world’s population.

Diminishing genetic and linguistic

diversity is matched by diminishing

biodiversity. Since the remaining

hunter-gatherers live in some of the

world’s most important biodiversity

hotspots this project will explore the

relationships between these key areas

of diversity for humanity’s general

resilience in a period of rapid natural,

social and technological change.

The Resilience Project studies hunter-

gatherers in Congo (Mbendjele),

Malaysia (Batek), Thailand (Maniq) and

the Philippines (Agta), using behavioural

ecology, life history theory, theories of

cooperation, cultural transmission and

genetics to explore how variation in

life history traits, kin selection, mating

systems, and cooperative behaviour

differentially contribute to hunter-

gatherer resilience in the past and

present .

The project is a 5-year research

programme funded by the Leverhulme

Trust, led by Dr Andrea Migliano in

collaboration with Dr Jerome Lewis,

Prof. Ruth Mace (UCL, Anthropology)

and Prof. Mark Thomas (UCL,

Department of Genetics, Ecology

and Evolution). We are a team of 20

researchers, including postdoctoral

researchers and PhD students,

interested in understanding the current

pressures and points of resilience of

these populations, and the important

adaptations for hunter-gatherers’

survival.

Hunter-Gatherer Resilience Project

RESEARCH

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

17

Substantial progress has been achieved in hunter-gatherer

and biodiversity research over the past century. However,

our understanding of the global variability, resilience and

dynamic connections between hunter-gatherer societies

and their environment remains fragmented. The goal of our

project is to address this gap through spatial and temporal

analyses of hunter-gatherer cultures across the world.

The Hunter-Gatherer World Map Project (HG.map) consists

of an international team of scholars with expertise in

anthropology, ethnography, geography, physical and social

modelling and environmental analysis. Together, we aim

to catalogue hunter-gatherer distribution and status

across the globe, and understand their present and future

environmental context. We employ a suite of methods

(including anthropological studies, geospatial analyses

and distribution modelling) to understand the factors

that impact the long-term survival of hunter-gatherer

societies. The ultimate question is not only why areas of

high biodiversity also tend to be culturally diverse, but also

how these areas of high biological diversity, which are of

great importance to hunter-gatherers, can be maintained.

Our project will:

- Generate a global map of the locations of hunter-gatherer

societies.

- Better understand the environmental, political and social

factors that correlate with current favourable areas for

hunter-gatherer societies.

- Assess future trajectories and potential pressures on the

cultural, biological, and ecological settings that hunter-

gatherer societies may face (including climate change).

Mapping Hunter-Gatherers

Human cultural diversity is concentrated in the remaining areas of global

biodiversity. The Hunter-Gatherer World Map seeks to catalogue this

remarkable overlap.

RESEARCH

18

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

Food sharing and cooperation

are at the centre of hunter-gatherers’

lifestyle. No other apes share food or

cooperate to the extent that humans

do. A complex network of sharing and

cooperation exist within camps and

between camps in different hunter-

gatherer groups, regulated by social

rules, friendship ties, food taboos,

kinship and supernatural believes.

Sharing is a crucial adaptation and one

that is believed to be central for the

evolution of mankind.

Rituals, Music and oral

traditions are at the centre of hunter-

gatherers’ cultural resilience. Great

similarities in vocal polyphonic singing

styles among African Pygmies and

similar taboos around reproduction

and food suggest ancient relationships

between these cultural traits. Our

project is studying the importance of

these traditions for the cultural and

biological resilience of different hunter-

gatherer groups.

Genetics is used to investigate

hunter-gatherer demographic history,

key phenotypic traits and adaptation

history. We are investigating changes

in hunter-gatherer population size

through time (before/after the spread of

agriculture started); levels of admixture

with neighbouring populations ; and

population-specic genetic adaptations,

such as adaptations associated with

diet, climate, and pathogens.

Research Topics

RESEARCH

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

19

The Agta of the Northern Luzon, Philippines,

live as mobile or semi mobile hunter-gatherers in

the mountain and coast of Northern Sierra Madre,

Isabela. Like many Hunter-gatherers in the Philippines,

deforestation associated with the expansion of

Agriculture and growing Philippine population has had a

signicant impact on the distribution and demography of

the Agta population. Currently there are between 1,500

and 2,000 Agta living in this area of Northern Sierra

Madre, where they continue to live in small semi-mobile

groups, depending on forest hunting and gathering as

well as marine resources for their subsistence.

The Agta speak Austronesian languages that are thought

to have been acquired after contact with agriculturalists

over the last few thousand years, and they are related

to other hunter-gatherers in the Philippines such as the

Aeta and the Batak. In spite of the language shift, many

of the Agta groups display remarkable resilience in their

way of life; while others are slowly shifting towards

more integrated markets.

The Mbendjele or BaYaka live in the western

Congo basin, in the northernmost regions of the Republic

of Congo. Some fifteen to twenty thousand Mbendjele

are estimated to live as hunter-gatherers in the rainforest

bordering Cameroon and the Central African Republic. Like

other Pygmy groups of central Africa, they have long-term

relations with sedentary farming communities, and speak a

Bantu language.

Also in common with other Pygmies, they have sophisticated

traditions of choral music, myth and ritual, and a deep

knowledge of the forest and its inhabitants. Although

increasingly under pressure from logging and conservation

interests to abandon their hunting and gathering lifestyle,

they maintain great pride in their way of life.

Field Work

RESEARCH

20

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

Bala bala bala / Konga konga konga

/ Eliki konga!… So sing the kids,

clapping their hands joyfully and inviting

us to join them. Every day kids are

around us, dancing, shouting, climbing

trees and making toy dolls, mimicking

hunters and forest spirits. At nights,

women sit on the plain ground screaming

the songs their ancestors have been

singing for thousands of years. They are

calling for the forest spirits. Soon the

spirits come: the men covered in forest

leaves, dancing in trance. I look at the

sky; the stars blink at me, I’m in another

universe. A universe which,

along with the joyful forest

people and beautiful animals,

has hundreds of stingless

bees that land on your head

and lick your sweat during

the day; and angry storms

that make you stay awake all

night worrying which of the

trees above your head will

fall first. As the pile of my

dirty clothes gets bigger, I wonder what

time of day will be the best to go to

the river for washing while avoiding the

infected ies. This is a parallel universe

that I am in – a universe which is full of

tough beauties. Deniz Salali

When we arrived in Longa, the rst

Mbendjele camp we visited, the children

ran after our truck to greet us. Seeing

hunter-gatherer camps and people

right in front of me, rather than on a

documentary, was denitely one of the

most exhilarating moments of my life.

It is difcult to encapsulate

all the laughs, bonding and

difculties we experienced

over our 10 weeks in the

rainforest.

The best part of eldwork

is the children: Before

arriving there is always

apprehension about how

you will be received, but the children

are just as excited to see, play with and

learn about you, as you are with them

– they are what I miss the most. The

other highlights were getting to see

the unimaginable talents these people

possess - they are magnicent singers

and clappers, making music completely

different to anything you’ve heard; and

they climb trees 40m high to collect

honey.

One of the hardest things about forest

life is not having the food you want --

after a few days I was already fantasizing

about Domino’s pizza. But I quickly

became accustomed to bathing in the

lake, pissing in the forest, and sleeping

in a tent. It’s definitely the most

memorable thing I’ve done.

Nik Chaudhary

Students Perspectives: Africa

RESEARCH

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

21

Students Perspectives: Asia

Batek: As an indigenous hunter-gatherer society in an

increasingly urban world, the Batek’s way of life is currently

under threat from government pressure, deforestation, and

tourism. I hope that through appreciation of their musical

practices, more can be understood about what is at the root

of their resilience in the face of these threats. Many cultures

differentiate music and language as separate methods of

communication, usually prioritising language as the most

effective and direct means of communication. Often,

however, cultures that have not had the direct experience

of literacy training are more likely to see music, language,

gesture, and dance as part of the same process of message

communication. Music - or rather the process of ‘musicking’

- can potentially tell us as much about the beliefs of such a

community as language.

As the Batek hunt and gather for their subsistence, an

intimate knowledge of and relationship to the forest is

essential to their survival. Deep care for the forest means

that the destruction of rainforests, for them, is equivalent

to the destruction of the world. The Batek are therefore

convinced of the urgent need to inform the world of the

dangers of losing the forests, not only for them, but for all of

us. They communicate their stories of warning through surat

– oral letters passed down through generations. In looking

at the ways the Batek ‘music’, and how they communicate

more broadly, I hope to gain an understanding of these surat,

and thus how the destruction of the forest is affecting their

world. Alice Rudge

Agta: As many people learned in the aftermath of typhoon

Haiyan, the Philippines, an archipelago of some 7,000 islands,

has thousands of small and isolated communities, accessible

only by boat or light aircraft. Communities in north-eastern

Luzon, the largest island in the Philippines and home to the

urban sprawl of Manila, are, however, isolated not by ocean

but by the Sierra Madre mountain range, which runs down

the eastern spine of the island and cuts down steeply to the

Pacic. This region is inaccessible by road and isolated to

such an extent that its inhabitants refer to the rest of the

islan d as the ‘mainland’.

As well as a modest population of farmers, the region is

home to the Agta, one of the few remaining populations

of ‘indigenous’ Filipinos who still have a largely hunter-

gatherer economy. For us, three PhD students who had

never conducted anthropological eldwork before, the boat

journey to Palanan was very exciting. We were desperate to

see Agta camped along the beach as we went past, individuals

we had come so far to see. When we landed in Palanan we

nally met a group of Agta women and children, and suddenly

the reality hit us that these were not some mystical, strange

individuals but a groups of mothers, fathers, brothers and

sisters trying to get along in their environment and ecology.

Even so, eldwork remained exciting and challenging (if a bit

hot and sweaty at times). We are looking forward to going

back next year and learning more about the Agta’s unique

adaptations to life.

Abigail Page, Daniel Smith & Mark Dyble

RESEARCH

22

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

What makes people fall in love? A good

sense of humour? Similar interests?

A physical attraction? When people

say that ‘there just was a chemistry

between us’ they may actually be on to

something. According to evolutionary

anthropologists, smell may be an

important factor in human mate choice,

which helps to increase individuals’

reproductive success. Experiments

have shown that women are more

attracted to the smell of men that differ

in a set of genes that are important for

the immune system, also known as

the major histocompatibility complex

(or MHC). The MHC helps the body

to decide if an antigen it encounters

belongs to the body, or is an invader. The

combination of two peoples’ different,

or complementary, MHCs gives their

offspring immunity to a wider range of

diseases, and therefore those offspring

are at an advantage. Women are able

to make very ne-grained choices as it

has been shown that they are able to

discriminate between the smells of men

that just differ in a few genes.

The first-year students on the

‘Introduction to Methods and

Techniques in Biological Anthropology’

set out to test if both men and women

use their noses to nd a mate. To this

end, each student wore a plain white

T-shirt for three nights in a row, and

brought the T-shirts to class in a sealed

plastic bag. Students then sniffed and

ranked each T-shirt according to

the pleasantness of its smell. These

data were then analysed using Social

Network Analysis. Two networks

were created, a ‘like’ network, and

a ‘dislike’ network, in which the

relationships between individuals were

given by how they rated each other’s

smell. Within these networks, the

percentage of reciprocal relationships

RESEARCH

Sniffing

out a

mate

Dr Nienke Alberts

“According to evolutionary

anthropologists, smell may

be an important factor in

human mate choice, which

helps to increase individu-

als’ reproductive success.”

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

23

RESEARCH

where calculated, in other words,

the proportion of total relationships

in which both individuals liked (or

disliked) each other’s smell. If smell is an

important part of human mate choice,

we would expect a high proportion

of relationships to be reciprocal, as

people with complementary MHCs

should rate each other’s odours highly.

These were however, not the results

we found. In the like network,

only 11-14% of relationships were

reciprocal, and this was 8-13% in the

dislike network. There were several

explanations for this low proportion of

reciprocity. Firstly, it may be that the

contraceptive pill inuenced some of

the results, as previous studies have

shown that the hormones in the pill

can interfere with the preference for

odours in both males and females.

Secondly, it may be that smells other

than body odour were used in ranking

the T-shirts. Some T-shirts had

remnants of perfume or body wash on

them, which made them very popular.

Other T-shirts had last nights curry all

down the front of it. And that never

helps with nding a mate.

A stricter protocol on not wearing

perfumes, eating, or smoking

whilst wearing the T-shirts for the

experiment, would eliminate this

possible interference of other smells.

By collecting additional information

on the use of the contraceptive pill,

we would further be able to control

for hormonal interference in odour

preferences. Together, this would give

a more robust test of whether humans

follow their noses to nd their perfect

partner.

24

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

EVENTS

A beginning for

LabUK

Carol Balthazar

PhD in Social and Cutural Anthropology

LabUK is a research platform created

by the UCL Anthropology Department

to bring awareness to the strong body

of anthropological research produced

among those of us who are researching

topics in the UK. At the beginning of

the 2013/14 Academic year, LabUK

officially started its activities with a

one-day workshop.

At the workshop, Masters students,

PhD’s and lecturers had the opportunity

to present their work and explore

potential synergies. The eleven pre-

circulated papers were presented in

four different sessions: “Otherness

within Britain”, “Play, Otherness and

Anthropology”, “LabUK, Why?” and

“Ethnography of Britain and Applied

Anthropology”. They included talks

on hospices and Facebook; UK gold-

workers trade, climbing walls, climate

change activist camps, fieldwork in

places for which there are no maps

(sic!) and several other subjects.

As the name of the platform suggests,

the discussions allowed the comparison

between ethnographies of the UK

but also encouraged the theoretical

problematization of national or

geographical boundaries in the discipline

of Anthropology. In this sense, the

workshop was a good opportunity

for the discussion of categories such

as “home” and “other” and other

potentially problematic traditional

anthropological dualities such as “us-

other”, “western-non western”. Are

we always some kind of “other”, even in

our own country? Is the ethnographer’s

task, to reinforce the existence of

otherness or is it the exact opposite,

to continually strive to become “one

of them”? Can performance and

play generate relevant tools for the

understanding of contemporary social

relations? And, what might be the

contribution of ethnography of Britain

– and other traditionally ‘less-noble’

ethnographic research objectives – to

an Anthropology that

seeks alternatives for the

future? Those were some

of the questions raised

and discussed during the

event. Inevitably the day

nished with thoughts on

the potential of applied

Anthropology, and

how anthropology may

contribute to mediation

in different grounds such

as the medical system and law.

All the workshop information, papers

and recorded presentations will soon

be available on the platform website.

The intention is that all members of

the department have access to this

content and may prot and contribute

to the platform. Future events will help

to shape the platform’s ambition; and

UCL members are encouraged to join

the group, suggest activities and help to

dene what is the LabUK.

For more information, please see the

platform website http://www.ucl.ac.uk/

labuk or contact LabUK coordinator

Joanna Cook.

“Cheering for Britain”, 2012

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

25

EVENTS

On Wednesday 23rd October, Anthro

Soc held their rst event of the year, a

debate on brain, mind, and meditative

therapies. Jo and Lucio both work on

the mind, but approach it from very

different perspectives. Lucio is an

evolutionary anthropologist, whose

research interest lies in discovering

what makes the human mind and brain

distinct from the brains and minds of

other animals. Jo Cook is a medical

anthropologist and has done eldwork

in Thailand in Buddhist monasteries,

and now works on the implementation

of Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy

(MBCT) as a treatment of depression

in Exeter.

Asking the questions were Henry

and Ali, members of Anthro Soc. The

debate opened with a set of quick-re

questions, where we learnt that if Lucio

were to be born again, he would like

to be Aristotle, and that surprisingly,

both our speakers knew to the day how

long they have been in working in the

department.

Then we got on to the serious matter

of the debate. First up for discussion

were the benefits and drawbacks of

awareness of routine actions. Whilst

awareness of one’s own body and it’s

movements is vital for Mindfulness

training, in high pressure situations,

such as a crucial tennis serve for

match point, a heightened awareness

of your well practiced serve is actually

counterproductive as your brain starts

to function as if it were the rst time you

have ever made that movement, so your

‘auto-pilot’ function is momentarily

lost. The intersections of Jo and Lucio’s

viewpoints were interesting because

although they are part of traditionally

contrasting disciplines, they had similar

ideas about the interrelatedness of

the mind and the body. Cartesian

Dualism, the idea that the mind is the

active subject presiding over the passive

object of the body, has been pervasive

throughout the history of medicine,

but both our speakers want to move

past that and explore the complexity

of the mind-body system. The results

of our poll were that the audience

mostly thought that mental and physical

illnesses should be treated differently -

but is this reective of a subscription to

Cartesian Dualism? This led to issues

of treatment of depression – how can

meditative and chemical treatments be

compared? Prescription medication can

be used during depressive episodes,

but can be very addictive, and cannot

guarantee the prevention of recurrence

of depressive episodes, whereas MBCT

is very effective at preventing relapse,

has no side effects but on the downside

it cannot be used as a treatment during

depressive episodes, and currently the

treatment has limited availability in the

UK.

Complementing the poll was an

interactive poster which invited

audience members to make a mark on

an image of the human body indicating

what they believed to be the location

of the human mind. The majority

of people circled the human brain.

Others, who seemed to be students

of Lucio’s ‘Human Brain, Cognition and

Language’ course, circled specifically

the prefrontal cortex – an area at the

anterior of the brain associated with

high level cognition. Other suggestions

were the whole body, the groin area, the

radical ‘it doesn’t exist’, and in language

– a suggestion by a PhD student and

seconded by a visiting speech sciences

student.

It was a thought-provoking debate,

which led to the inevitable conclusion

that nobody can say where the mind is,

as there will always be multiple answers

that are equally legitimate. Jo and Lucio

will have to keep asking themselves, and

each other: Where is my mind?

Poppy Walter

3rd Year BSc Anthropology

Piece of Mind: A Debate

on the Path to Happiness

Jo Cook and Lucio Vinicius met for the

first time at Anthro Soc’s first event of the

year

26

ANTHROPOLITAN WINTER 2013/2014

DEPARTMENT NEWS

Recently

Awarded PhDs

Ellie Reynolds – Substance, embodiment and

domination in an orgasmic community

Razvan Nicolescu – Boredom and social

alignment in rural Romania

Shu-Li Wang – The politics of China’s cultural

heritage on display - Yinxu Archaeological Park in

the making

Peter Oakley – The creation and destruction of

gold jewellery

Matan Shapiro – Invisibility as ethics: affect,

play and intimicy in Maranhão, Northeast Brazil

New

Appointments

Dr Nienke Alberts - Teaching Fellow

in Biological Anthropology

Nienke Alberts’ main interest is the dynamics

of groups in human and non-human primates.

She uses modelling techniques, such as social

network analysis and agent-based modelling, to

answer questions about the factors that inuence

social behaviours, social relationships, and the

structure of social groups. She researched the

grouping patterns of olive baboons in Nigeria for

her PhD, and more recently has investigated the

group structure of Cape Mountain Zebra in South

Africa. She has also worked with free-ranging

chimpanzees, and has done research on the

spacing of Hanuman langur reproductive cycles.

Before joining UCL, Nienke held posts at the

University of Roehampton, and Manchester

University, and was nominated as a council

member of the Primate Society of Great Britain.

In the eld with Fadi, Kaiye, Ann & new infant

New Books by Staff

Cover Photo Courtesy of Christopher Pinney www..ucl.ac.uk/anthropology

/UCLAnthropology