Retail payment systems in

New Zealand

Issues Paper

October 2016

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

2

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

Contents

Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 2

How to have your say .................................................................................................................... 3

Glossary of terms .......................................................................................................................... 5

Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 6

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 11

Structure of this Issues Paper ...................................................................................... 11 1.1

What are retail payment systems? ............................................................................. 12 1.2

Objectives .................................................................................................................... 12 1.3

Regulation of retail payments in New Zealand ........................................................... 13 1.4

2. Payment systems in New Zealand ....................................................................................... 16

Introduction ................................................................................................................ 16 2.1

Parties in the system ................................................................................................... 17 2.2

Types of payment card and the types of transactions ................................................ 18 2.3

Methods of switching .................................................................................................. 20 2.4

Trends in usage of payment options ........................................................................... 21 2.5

Emerging payment methods ....................................................................................... 23 2.6

3. Market business models and resource costs ...................................................................... 27

Switch-to issuer transactions ...................................................................................... 27 3.1

Switch-to-acquirer transactions .................................................................................. 30 3.2

Ancillary relationships ................................................................................................. 44 3.3

Resource costs ............................................................................................................. 45 3.4

4. Issues identified................................................................................................................... 47

Overview ..................................................................................................................... 47 4.1

The interchange business model is resulting in inefficient outcomes in the credit card 4.2

market ..................................................................................................................................... 48

Inefficiencies could develop in the debit market ........................................................ 54 4.3

There is a large gap between the MSFs faced by small and large merchants ............ 62 4.4

Assessment against objectives .................................................................................... 64 4.5

5. Possible next steps .............................................................................................................. 65

Immediate actions ....................................................................................................... 65 5.1

Further work to address the wider policy issues ........................................................ 66 5.2

Recap of questions ...................................................................................................................... 69

Annex 1: International experiences ............................................................................................ 71

Annex 2: The Commerce Commission’s 2009 settlement .......................................................... 77

Annex 3: List of stakeholders ...................................................................................................... 79

Annex 4: Key figures used in this Issues Paper ........................................................................... 80

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

3

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

How to have your say

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) seeks written submissions on the

issues raised in this document by 5pm on Tuesday, 13 December 2016. Questions are posed

throughout the document to guide your submission.

Your submission may respond to any or all of these questions. We also encourage your input

on any other relevant issues. Where possible, please include evidence to support your views,

for example references to independent research, facts and figures, or relevant examples.

You can make your submission:

• By sending your submission as a Microsoft Word document to

competition.policy@mbie.govt.nz

• By mailing your submission to:

Competition and Consumer Policy

Building, Resources and Markets

Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment

PO Box 1473

Wellington 6140

New Zealand

Please direct any questions that you have in relation to the submissions process to Steven Sue

on steven.sue@mbie.govt.nz

.

Use of information

The information provided in submissions will be used to inform MBIE’s policy development

process, and will inform advice to Ministers on retail payment systems.

We may contact submitters directly if we require clarification of any matters in submissions.

Submissions are subject to the Official Information Act 1982. MBIE intends to upload PDF

copies of submissions received to MBIE’s website at www.mbie.govt.nz. MBIE will consider you

to have consented to uploading by making a submission, unless you clearly specify otherwise

in your submission.

Please set out clearly with your submission if you have any objection to the release of any

information in the submission, and in particular, which parts you consider should be withheld,

together with the reasons for withholding the information. MBIE will take such objections into

account and will consult with submitters when responding to requests under the Official

Information Act 1982.

If your submission contains any confidential information, please indicate this on the front of

the submission. Any confidential information should be clearly marked within the text. If you

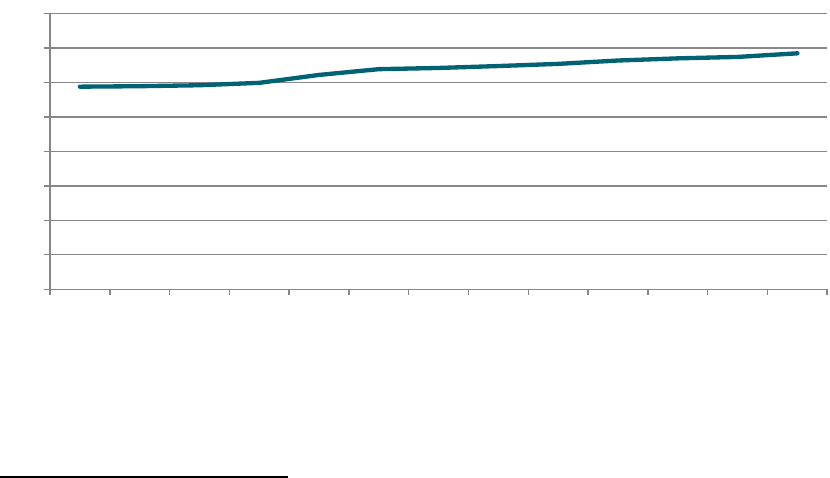

wish to provide a submission containing confidential information, please provide a separate

version excluding the relevant information for publication on our website.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

4

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

Private information

The Privacy Act 1993 establishes certain principles with respect to the collection, use and

disclosure of information about individuals by various agencies, including MBIE. Any personal

information you supply to MBIE in the course of making a submission will only be used for the

purpose of assisting in the development of policy advice in relation to this review. Please

clearly indicate in your submission if you do not wish your name to be included in any

summary of submissions that MBIE may publish.

Permission to reproduce

The copyright owner authorises reproduction of this work, in whole or in part, as long as no

charge is being made for the supply of copies, and the integrity and attribution of the work as

a publication of MBIE is not interfered with in any way.

ISBN 978-0-947524-29-6 (online)

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

5

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

Glossary of terms

Acquirer: An organisation, typically a bank, which provides access to the payment system on behalf of

merchants for the clearing and settlement of funds in a transaction. An acquirer may or may not also be the

bank that provides other services to a merchant, such as lending and deposits.

Cardholder/customer/consumer: Buys goods and services from merchants in exchange for payment.

Card-present transaction: Any transaction where a customer is in the same physical location as the merchant.

Card-not-present transaction: Any transaction made online, over the phone, or in other situations in which a

customer is not in the same physical location as the merchant.

Contactless transaction: Any transaction made using contactless technology (such as Visa PayWave and

MasterCard PayPass) where the customer is in the same physical location as the merchant. Includes card- and

app-based payments.

Customer interface: Either the physical terminal (card-present) or digital customer gateway (card-not-present)

through which the customer makes a payment to a merchant.

Direct entry: A method of transferring funds between bank accounts that does not rely on scheme or

proprietary EFTPOS rails. Also known as account-to-account payments. Can include manual bank transfers,

automatic payments, direct debit transactions, etc.

Interchange fee: A payment made from an acquirer to an issuer (or occasionally the reverse), each time certain

forms of retail payments are made.

Issuer: An organisation, typically a bank, which issues cards and provides debit and/or credit services to

customers.

Merchant: A party that provides goods or services in return for payment. Includes retailers, wholesalers,

utilities companies, and central and local government.

Merchant service fee (MSF): A payment made from a merchant to an acquirer each time certain forms of retail

payments are made.

Proprietary EFTPOS: The ‘traditional’ form of card payment in New Zealand, which utilises mag-stripe

technology. Standards are maintained by Payments New Zealand, but no ‘owner’ as such.

Resource cost: The economic resources expended by system participants to ‘produce’ a payment. This includes

fraud prevention costs, authorisation and transaction processing costs, and other back-office costs. Excludes

transfers between parties, such as rewards or MSFs.

Scheme: Includes Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and Diners Club. Schemes develop technology and base

product features, and set the commercial model and card system rules. They may issue cards and attract

merchants through banks (open system – Visa and MasterCard) or directly (closed system – American Express,

Diners Club, etc.). Only relevant for non-proprietary-EFTPOS transactions.

Steering: When a merchant does not accept, or discourages, payment via certain means.

Surcharging: When a merchant charges more to accept payment via certain means.

Switch: Payments infrastructure that sends transaction information to the correct issuer or acquirer

(depending on the type of transaction) so that the funds can be taken from the customer's account and

delivered to the merchant.

Switch-to-acquirer: The process by which information about certain card payments, notably credit cards,

contactless scheme debit, card-not present and international transactions, is sent between institutions.

Attracts interchange (except for closed schemes) and MSFs.

Switch-to-issuer: The process by which information about certain card payments, notably proprietary EFTPOS

and inserted/swiped scheme debit, is sent between institutions. Attracts no interchange fee or MSF.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

6

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

Executive Summary

Overview

1. In February 2016, the Minister of Finance and the Minister of Commerce and Consumer

Affairs commissioned a study into New Zealand’s retail payment system in the context

of:

• merchant concerns about increasing fees for the processing of electronic

transactions;

• industry developments, including the adoption of new technologies; and

• ongoing reforms to the oversight and regulation of retail payment systems in

overseas jurisdictions.

2. In addition to outlining how retail payment systems work in New Zealand, this Issues

Paper looks at the economic outcomes that result from New Zealand’s retail payment

system (as opposed to, for example, financial system stability outcomes which are

considered by the Reserve Bank). It focuses predominantly, but not exclusively, on credit

and debit cards, in reflection of their dominance of retail payments.

3. This Issues Paper was developed by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and

Employment so the views expressed in this paper should be read as the Ministry’s

preliminary views, not necessarily those of the Government.

4. The Government is now wishing to test the Ministry’s analysis with the public. Retail

payment systems are extremely complex and it is important to fully understand the

issues before the Government decides whether to proceed any further. While the

Government is not at the stage of considering options, it is also important to bear in

mind that if we proceed to that stage, any potential solution would need to be tested

against the harm it is designed to address and that all the consequences are taken into

account.

5. For example, some overseas jurisdictions have regulated interchange fees to address the

issues discussed in this Issues Paper. While this approach is designed to address the

issues at hand by reducing the ability of banks to provide generous rewards to

incentivise credit card use, it could also see banks increase annual fees on credit cards to

maintain reward levels, or reduce the generosity of reward programmes. It is therefore

important to understand all of these impacts when considering the issues.

Background

6. Each year consumers make approximately 1.5 billion electronic card transactions,

representing more than $76 billion in expenditure. Transactions made using electronic

cards are responsible for around two thirds of retail trade revenue in core industries,

and this share of retail revenue has been growing steadily compared to other payment

methods such as cash. Within card-based payments, currently around 42 per cent of

transactions (by value) are made using credit cards, 36 per cent using proprietary

EFTPOS, 15 per cent using swiped/inserted scheme debit, and 7 per cent using

contactless scheme debit. While cash remains an important retail currency, New

Zealand has the lowest proportion of cash to GDP in circulation in the world. The

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

7

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

payment card market can be considered to be at saturation, with 93.8 per cent of adults

in possession of and using a debit card.

7. Electronic payments provide a number of key benefits to consumers, merchants (such as

retailers), and government. This includes greater convenience; reduced risk of fraud,

theft, and bad debts; the ability to purchase online; reduced cash-handling costs; greater

certainty of tax revenue; and – in the case of credit cards – the ability to smooth

consumption over time.

8. We estimate that the inherent ‘resource cost’ of processing card payments each year is

around $950 million, or roughly 1.3 per cent of the value of the $76 billion dollars of

transactions made on payment cards across the economy. This is the economic resource

required to facilitate these transactions. Merchants carry the bulk of the direct costs,

paying an estimated $461 million in merchant service fees in 2015. We expect that these

fees could increase significantly in coming years with rapid uptake of contactless

payment. This could increase the fees paid by another $216 million annually.

9. In preparing this Paper, we asked the following questions:

• Are consumers and merchants benefiting from ongoing innovation?

• Are card payment systems being used efficiently?

• Are consumers and merchants bearing a fair share of the costs?

Issues identified

10. The Ministry has found that the market dynamics suggest cause for concern in both the

credit and debit card markets.

Issue 1: Economic inefficiency in the credit card market

11. We consider that there is economic inefficiency in the credit card market. While credit

cards provide a number of benefits to both consumers and merchants, we estimate that

current market incentives drive at least $45 million per year of additional cost to the

economy through the use of more expensive credit card networks compared to lower

cost EFTPOS networks. This figure focuses on the transactions that are induced by the

incentives in the system, not the ones that are placed on credit cards on the basis of

their inherent credit functionality or their ability to be used overseas. $45 million

represents 5 percent of the total resource cost for processing electronic card payments

in New Zealand, and around 0.13 per cent of the total value of expenditure on credit

cards in the year to March 2016.

Issue 2: Increased prices for all consumers, with only higher-income consumers

benefiting from rewards

12. The costs of merchant service fees are ultimately likely to be passed onto consumers

through the price of goods and services. Some of the cost that is passed on is used to

fund rewards and other inducements for using credit cards. We estimate that merchants

have to increase their prices to all consumers by around $187 million per year to fund

rewards paid to certain credit card users. Because of the way credit card reward

schemes are structured, this leads to an annual regressive cross-subsidy of $59 million

from low-income to high-income households. These costs are ongoing, so they add up

over many years.

13. Issues 1 and 2 are a result of the business model under which credit card schemes

operate. Payment systems are two-sided markets, in that they rely on uptake by both

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

8

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

consumers and merchants to be valuable. At the centre of this business model is the use

of interchange fees, which place charges on merchants and pass them on to the banks

that issue credit cards. Interchange fees allow banks that issue credit cards to incentivise

credit card use, such as through rewards schemes, effectively paying many consumers to

use their credit card instead of the cheaper EFTPOS system. These interchange fees are

then passed onto all consumers (irrespective of the type of card used) through higher

prices because most merchants do not recover those fees through surcharges.

14. Credit card schemes have traditionally operated under this interchange business model,

but there is evidence that the inefficiencies generated are increasing, with recent

competition driving up interchange fees and the value of rewards. We are also seeing

banks “flipping” credit card users to higher cost premium cards that offer higher levels

of rewards. All but the largest merchants hold little bargaining power over these fees,

with consumer demand giving them little choice but to accept payment via credit card.

15. These outcomes are not the result of irrational or anti-competitive behaviour by any

particular party. It is completely rational for credit card holders to maximise usage to

obtain rewards in the presence of distorted price signals. Similarly, the setting of

interchange and use of rewards schemes is perfectly rational profit maximising

behaviour on the part of the schemes and the banks. Despite this individual rationality,

without price signals, this business model results in an inefficient overall outcome.

16. Based on the information available to us, merchants in New Zealand appear to pay

higher fees to accept payment via credit card than merchants in some overseas

countries. New Zealand’s credit interchange fees are roughly comparable to what is paid

in the USA and Canada, where credit interchange is not regulated. However, New

Zealand interchange rates and merchant service fees are significantly higher than those

in regulated environments, such as the European Union and Australia. The overall higher

cost of electronic transactions may be offset to some extent because no charges are

applied to EFTPOS and swiped/inserted scheme debit transactions, which currently

account for around half of all card transactions.

Issue 3: Emerging inefficiency in the debit card market

17. Similar market dynamics are beginning to emerge in the debit card space, with rapid

growth of the market share of scheme debit products in place of New Zealand’s

proprietary EFTPOS system. Contactless and online scheme debit now make up about 15

per cent of the debit card market, up from about two per cent two years ago. New

Zealand is different to many economies in still having a domestic EFTPOS system that

does not charge per-transaction fees to merchants. It is, however, unlikely that such a

model is sustainable when competing with scheme products, regardless of the

underlying efficiency of domestic EFTPOS.

18. The growth of scheme debit products provides many benefits – such as additional

security, and the ability to make contactless and online transactions – in contrast to

proprietary EFTPOS which has suffered from a sustained lack of investment.

19. Nevertheless, such benefits come with additional cost, as schemes have introduced

interchange fees on contactless (and online) debit transactions, in contrast to

proprietary EFTPOS, which does not attract such fees. We estimate that fees to

merchants on scheme debit transactions could rise by $216 million per year if

contactless usage increases to 60 per cent of debit payments.

20. The imposition of fees in itself is not inherently a problem, given that the lack of fees is a

key reason behind the lack of investment in proprietary EFTPOS. However, as

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

9

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

contactless debit becomes entrenched, we are concerned that the competitive

constraint on fees to merchants currently provided by proprietary EFTPOS will reduce.

This could result in the interchange dynamics we currently see in the credit card market

driving inefficiency and large scale cross-subsidisation in the debit market as well.

Issue 4: Barriers to entry in the debit market

21. We are also concerned about the impact that a scheme-dominated debit market would

have on market entry and expansion. While it is possible for a new entrant to disrupt the

market before full scheme dominance occurs, the interchange model sets up entry and

expansion barriers by giving card issuers (banks) significant financial incentives to favour

payment systems that offer interchange income. Potential new payment options would

likely need to compete on an interchange-like system (bidding up prices and distorting

price signals) in addition to providing improved functionality, if they are to be attractive

to consumers and banks.

Issue 5: Impact on small business

22. In addition to the inefficiency that the scheme interchange model is driving, there

appears to be systemically higher costs placed on smaller merchants to pay for the

processing of retail transactions. The interchange charged for small merchants can in

some cases be two and a half times the interchange rates for the largest, ‘strategic’

merchants. While there is likely to be some cost differential underlying the gap between

fees charged to large and small merchants, a closer look at the marginal costs involved

in processing transactions suggests that differences in underlying system costs are

unlikely to be a dominant driver of the growing differential in merchant service fees

between small and large merchants. If the spread were to increase further, we are

concerned that the disadvantage faced by smaller merchants could ultimately harm

retail competition.

Next steps

23. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment considers that the nature and the

scale of the issues identified in the credit market, and the potential for these issues to

develop in the debit market, warrant additional work to address these issues. Similar

issues have been identified around the world, and it is only in countries where some sort

of regulatory intervention has occurred that these impacts have been addressed.

24. The Government is now testing the Ministry’s analysis and proposed next steps before

any decision is made about whether to progress this work further. Questions have been

posed throughout this paper for your consideration.

25. If the Government does choose to progress this work further, the complexity of the

retail payment system and the potential pace of change means that it will be important

for the following to be taken into account when developing a way forward:

• the New Zealand context;

• the effectiveness and net benefits of each option;

• any consequential impacts on consumers and merchants, investment in innovation,

and development of the broader retail payments sector; and

• the timeliness of any intervention.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

10

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

26. Should further work be undertaken, it would involve close engagement with

stakeholders, in order to ensure that any proposals make the best use of industry

expertise and take into account any stakeholder concerns.

27. The Ministry considers that further investigation would be worthwhile on the following:

• The costs and benefits of applying interchange regulation to the credit market (and

the under which it would be applied in the debit market).

• Whether there are economic, institutional and technical barriers to entry and

expansion for new payment methods in the debit market, and options for addressing

any such barriers.

• Examination of other options, including: whether the governance of payment

systems can be improved; whether lighter-touch regulation, such as an industry code

of conduct, would have merit; whether EFTPOS could be made a sustainable

alternative to scheme debit products; and whether the retail payment system, or a

part of the system, should be treated like a utility.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

11

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

1. Introduction

28. In February 2016, the Minister of Finance, the Hon Bill English; and the Minister of

Commerce and Consumer Affairs, the Hon Paul Goldsmith, asked officials to undertake a

study into retail payment systems in New Zealand. The objective of the study was to test

whether the system – in its current state, and as it is likely to develop in the future – is

delivering good outcomes for consumers and merchants and the New Zealand economy

as a whole.

29. The decision to undertake a study into retail payments was triggered by a number of

factors, including:

• merchant concerns about increasing fees for the processing of electronic

transactions;

• industry developments, including the adoption of new technologies; and

• ongoing reforms to the oversight and regulation of retail payment systems in

overseas jurisdictions.

30. Officials from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) provided the

Government with a report in July 2016. It was developed in consultation with around 30

industry participants, including Retail New Zealand; small and large retailers; all major

banks, credit card schemes and ‘switches’; Consumer New Zealand; market challengers;

and independent experts. Some stakeholders provided us with non-public data to

support us to draw conclusions. While we have included as much information as

possible in this document, we have not published commercially sensitive information.

31. The report was independently reviewed by Dominic White of Pebble Payments and Mike

Laing of LWT Advisers. Both are payment systems specialists based in Australia.

32. The Government is now seeking feedback from stakeholders and the wider public on the

issues and proposed next steps outlined in this report. Questions have been posed

throughout this paper for your consideration.

Structure of this Issues Paper 1.1

33. The remainder of the Introduction sets the scene for the analysis that follows, by

defining the scope of the issues addressed in this Issues Paper, proposing public policy

objectives for retail payment systems, and outlining how retail payment systems are

currently regulated in New Zealand.

34. Section 2 outlines how retail payment systems work – the main participants in the

system, the mechanics of how payments are processed, and trends in how different

retail payment options are being used.

35. Section 3 looks at the business models underpinning retail payment options, how costs

and charges flow through the system, and the incentives that result. This section also

considers the relative resource cost of putting payments through the various payment

channels.

36. Section 4 presents the issues we have identified with retail payment systems, as they

currently operate. This section looks at whether the market set up is achieving the sorts

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

12

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

of economic outcomes that are desirable, and whether this is likely to be the case as the

market evolves.

37. The final section outlines our preliminary thinking about next steps to address these

issues.

What are retail payment systems? 1.2

38. A payment system can be defined as the arrangements that allow consumers,

businesses and other organisations to transfer funds usually held in an account at one

financial institution to another. It includes the payment instruments – cash, cheques and

electronic funds transfers which consumers use to make payments – and the usually

unseen arrangements that ensure that funds move from accounts at one financial

institution to another.

1

39. There are various layers to a payment system:

• the underlying network or “rails”, each with its own technical and operational

standards – such as the Visa or MasterCard card networks, the Electronic Funds

Transfer at Point of Sale (EFTPOS) system, ‘direct entry’ into a bank account, or cash;

• the product or method of payment that sits on these rails – such as automatic

payments, direct debits, bank transfers, credit cards, online banking and mobile apps,

scheme debit cards, and proprietary EFTPOS cards; and

• the initiator of the transaction – i.e. consumer, business, or government.

40. This study considers retail payment systems, which we take to mean a system that is

used to clear (the transmission of information through the system to authenticate

identities and the availability of funds) and settle (the actual transfer of funds between

accounts) financial transactions between consumers and merchants

2

in return for goods

and services. Retail payment systems are distinguished from large-value payment

systems, which largely involve transactions made between financial institutions.

41. This study focuses particularly, but not exclusively, on card networks (Visa and

MasterCard) and the EFTPOS system, although other underlying networks and products

– including potential emerging disruptors – are considered throughout this report as

comparisons. While our focus is primarily on transactions made by consumers, many of

the issues discussed will nevertheless apply to business-to-business transactions.

42. Retail payment systems involve network effects, in that the value of the payment

system as a whole rises as more people use it. In particular, retail payment systems are a

form of two-sided market. Essentially, this means that for a given system to be

successful, it must attract both consumers and merchants to use its system. No

consumer will use a payment method if it is not accepted by a merchant, and no

merchant will accept a payment method that is not used by any consumer.

Objectives 1.3

43. This study is focussed on the economic outcomes delivered by retail payment systems in

New Zealand. This is complementary to the objectives held by other regulatory bodies in

New Zealand. For example, it is vital that payment systems are safe, secure and subject

1

Reserve Bank of Australia. (n.d.). Payments System. Retrieved from http://www.rba.gov.au/payments-

and-infrastructure/payments-system.html.

2

We use this term in a relatively wide sense in this Issues Paper to include payments made by

consumers to retailers, wholesalers, utilities companies, and central and local government.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

13

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

to prudential supervision. However, we do not focus on these objectives here, as the

Reserve Bank largely holds responsibility for these outcomes in its prudential role.

44. In considering whether good economic outcomes are being delivered, we have used the

following objectives to assess New Zealand’s retail payment systems:

• Objective One: There is innovation and development of payment options that are

valued by consumers and businesses.

• Objective Two: Resources are allocated efficiently at a system level. In the context of

retail payments, this means that the mix of transaction methods used represents the

underlying preferences of consumers and merchants, taking into account the

marginal benefits and costs of certain forms of payment to the system as a whole.

• Objective Three: The cost associated with payment systems is distributed fairly

across consumers and merchants at an individual level.

45. These objectives – of innovation, efficiency, and fair distribution of cost – are tied to the

Government’s priority of building a more productive and competitive economy.

1 Are these objectives for retail payment systems appropriate?

46. We have not explicitly considered the competitiveness of the market. Competition can

take place within a payment system (such as between Visa and MasterCard), and

between payment systems (such as between credit cards and proprietary EFTPOS). In

terms of the former, as will be discussed throughout the Issues Paper, the two-sided

nature of retail payment systems means that it is possible for there to be competition

within a payment system, but for this to result in inefficient overall outcomes. In terms

of the latter, we see the outcomes (as captured by Objectives One to Three) as more

important than the input (i.e. the number of competing payment networks).

47. The ability to extract excessive profits is usually checked by competitive processes. We

have not examined profit levels, and whether these are ‘reasonable’, at any level of the

market. Such an exercise would be resource-intensive and difficult to undertake based

on publicly-available data. The analysis in this Issues Paper instead centres on the

economic incentives faced by market participants.

Regulation of retail payments in New Zealand 1.4

48. Retail payment systems are subject to relatively light-handed regulation in New Zealand.

Nevertheless, the following government and non-government regulatory bodies have

some form of oversight of their operation.

1.4.1 Prudential and system stability: Reserve Bank of New Zealand

49. Under the Reserve Bank Act 1989, the Reserve Bank has a mandate to promote the

maintenance of a sound and efficient financial system. In practice, the Reserve Bank has

not tended to treat efficiency as a standalone objective, but rather something that

should be pursued in conjunction with its soundness objective. Partly this is because a

focus on soundness is inherent in prudential regulation, and partly it is because

soundness and efficiency are mutually supporting concepts over the longer term.

50. In light of the fact that the Reserve Bank does not treat efficiency as a standalone

objective, it has minimised its role in respect of efficiency issues to a focus on access to,

and governance of, payment systems, minimising regulatory barriers to entry and

compliance costs, and effective market disclosure on soundness issues. As a result, the

performance and efficiency (allocative, dynamic, and productive) of retail payment

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

14

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

systems are not the primary focus of the Reserve Bank. This is in contrast to its

counterparts in countries such as Australia, which has a more direct ‘efficiency’ element

in their mandate. Since 2012, the Reserve Bank has been undertaking a review of its

oversight of financial market infrastructures (FMIs). That work is not designed to alter

the Reserve Bank’s approach to the retail payment systems we consider here.

1.4.2 Rules and standards for interoperability: Payments New Zealand

51. Payments New Zealand is the operator of a number of payment systems in New Zealand

(including the Consumer Electronic Clearing System, which includes proprietary EFTPOS).

It aims to promote “simple, innovative, and secure payment systems in New Zealand”.

Payments New Zealand was established in 2010 by eight banks (the shareholders) with a

mandate to open access to and preserve the integrity of New Zealand’s payment

systems. Prior to Payments New Zealand’s establishment, many of its functions were

undertaken by the New Zealand Bankers’ Association.

52. Payments New Zealand’s participants are banks that have joined one or more of its

clearing systems. Its members are payment system organisations (such as card schemes,

merchants, smaller non-shareholding banks, and payments infrastructure owners) that

want to be actively involved in the ongoing development and strategic direction of

payment systems. Its Board has 11 Directors made up of an Independent Chair, two

further Independent Directors and a Director appointed by each shareholder.

53. Payments New Zealand’s role is to:

• Manage the rules and standards of its payment systems.

• Encourage and facilitate new participants in its payment systems.

• Facilitate interoperability of payments between its Participants.

• Promote interoperable, innovative, safe, open and efficient payment systems.

54. In respect of the Consumer Electronic Clearing System, Payments New Zealand sets

standards relating to:

• What an EFTPOS card must have and do, such as the requirement for a PIN.

• What a merchant must do, such as make available a receipt.

• The minimum requirements of the terminals that cardholders use to initiate their

transactions.

• What, how, and when information gets exchanged through a switch.

55. Payments New Zealand has no (self-defined) role in determining the allocation of costs

or incentives within the retail payments system, or the business models that schemes

operate under.

1.4.3 Competition issues: Commerce Commission

56. The Commerce Commission (the Commission) has no prescribed role in relation to retail

payment systems, other than through its general role in enforcing the Commerce Act

1986, with the aim of promoting competition in markets for the long-term benefit of

New Zealand consumers.

57. In 2009, the Commission reached a settlement with the card schemes and major banks,

in which the parties made a number of undertakings to address what the Commission

considered was anti-competitive conduct in the operation of retail payment systems.

Annex 2 summarises the detail of the settlement.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

15

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

58. The settlement with banks and schemes expired in 2013. However, the settlement

continues to have residual impact. This is because if any of the parties re-commence any

of the practices that the Commission deemed to be anti-competitive, they may be re-

challenged for potentially breaching the Commerce Act. The exception may be the level

of interchange fees, which is not necessarily a breach of the Commerce Act in itself.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

16

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

2. Payment systems in New Zealand

Introduction 2.1

59. Electronic payment systems are a key piece of infrastructure for commerce. While

alternative payment options (such as cash and cheques) remain, they are increasingly on

the fringe and compete poorly with their electronic competitors in a number of

dimensions. For example, electronic payments:

• Often provide greater convenience for consumers (such no need to visit a bank or an

ATM to withdraw cash, greater payment speed, and the ability to track and record

transactions).

• Allow consumers to purchase online with ease.

• Avoid the cost to merchants associated with processing cash and cheques (although

as discussed later, electronic payments are by no means costless).

• May reduce the risk of bad debts, and cash and cheque-related fraud and theft.

• In the case of credit cards, allow consumers to smooth consumption over time (this

also means that merchants do not need to operate their own credit schemes).

• Generate greater certainty of tax revenue for governments.

Box 1: The value of credit cards for merchants

Many of the stakeholders we spoke to emphasised the value that electronic payments,

particularly credit cards, provide to merchants. These included the ability to accept

international transactions, the avoided cost of cash acceptance, payment guarantees against

fraud and credit losses, prompt payment benefits, and increased sales from existing and

new customers.

As noted above, electronic payments, including credit cards, unquestionably provide a

number of benefits to both merchants and consumers. However, we consider that the levels

of some of these benefits are contestable. For example:

• Some parties noted that the value of average credit card transactions is higher than the

value of cash or debit transactions, and viewed this as evidence that credit cards

encourage higher levels of spending. An alternative interpretation is that any increase in

spending in the current period is countered by a reduction in spending in future periods,

and that higher credit card transaction values relative to other methods is correlation,

rather than causation. That is, higher-income individuals usually have larger than

average transaction sizes, and often use credit cards, but their transaction size would be

unlikely to change if they used a different payment method.

• Some stakeholders also noted that the cost of payment card fraud sometimes rests with

merchants, i.e. it is not always covered by scheme or bank payment guarantees.

• Similarly, while cash is unquestionably costly to process for merchants, we consider that

many of these costs are fixed, and unlikely to disappear without a complete withdrawal

of cash from circulation.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

17

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

60. New Zealand is highly regarded internationally for having one of the most developed,

dynamic, safe and secure payment systems in the world.

3

In line with this, uptake of

electronic payments in New Zealand is high: 93.8 per cent of adults have and use an

EFTPOS/debit card; New Zealand has the highest number of electronic payments made

per capita; and New Zealand has the lowest proportion of cash to GDP in circulation.

4

Furthermore, a 2014 survey ranked New Zealand as the number one global pioneering

payments market. This was based on consumer preferences for using electronic

payment options for low-value payments, willingness to use contactless forms of

electronic payments, and receptivity to changes in electronic payments.

5

61. As will be discussed later, much of this is attributable to the business model that

underpinned the rollout of proprietary EFTPOS, which encouraged almost universal

acceptance of card payments by merchants.

62. The remainder of this section outlines at a high level the main participants involved in

retail payment systems in New Zealand, the main types of card payment, and how these

payments are processed. It also briefly outlines emerging payment methods, such as

Apple Pay.

Parties in the system 2.2

63. There are a number of parties involved in any card-based transaction. The parties

involved and the interactions between them will differ depending on the type of card

being used. Nevertheless, the key parties and their key roles include:

• Cardholder/customer/consumer: Buys goods and services from merchants in

exchange for payment.

• Merchant: A party that provides goods or services in return for payment. Includes

retailers, wholesalers, utilities companies, and central and local government.

• Issuer: An organisation, typically a bank, which issues cards and provides debit

and/or credit services to consumers.

• Acquirer: An organisation, typically a bank, which provides access to the payment

system on behalf of merchants for the clearing and settlement of funds in a

transaction. An acquirer may or may not also be the bank that provides other

services to a merchant, such as lending and deposits.

• Scheme: Includes Visa, MasterCard, American Express and Diners. Schemes develop

technology and base product features, and set the commercial model and card

system rules. They may issue cards and attract merchants through banks (open

system – Visa and MasterCard) or directly (closed system – American Express, Diners

Club, etc.). Only relevant for non-proprietary-EFTPOS transactions.

• Switch: Infrastructure that sends the transaction information to the correct card

issuer or acquirer (depending on the type of transaction) so the funds can be taken

from the consumer's account and delivered to the merchant. Switching functions can

be performed by various parties, including stand-alone switches (most notably

3

Payments New Zealand. (2016). Benchmarking New Zealand’s payment systems. Unpublished.

4

Payments New Zealand. (2015). Are our payment systems as good as we think they are? Retrieved

from http://www.paymentsnz.co.nz/articles/are-our-payment-systems-as-good-as-we-think-they-are

.

5

RFIntelligence. (2014). Identifying global leaders in the race to transform national payment markets.

Retrieved from

http://www.rfintelligence.com/downloads/RFi_Global%20Report%20May%202014%20-

%20FINAL%20VERSION.pdf

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

18

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

Paymark), schemes, and vertically-integrated terminal providers and customer

gateways (such as Verifone and Payment Express). The term here is distinguished

from an inter-bank switch that processes high-value payments, which is not further

discussed in this Issues Paper.

• Customer interface: Either the terminal hardware and software (for card-present

transactions) or digital customer gateway (for card-not-present transactions) through

which the customer makes a payment to a merchant.

Types of payment card and the types of transactions 2.3

64. This subsection outlines the types of debit and credit cards that are available, the types

of transactions that they can be used for, and how they are processed (or “switched”) in

the system. These relationships are summarised in Table 1. The method of switching is

important because it is tied to the business model applied to the transaction by banks

and schemes. This is discussed further in Sections 3 and 4.

Table 1: Cards, transactions and switches

Type of card Type of transaction Method of switch/network

Proprietary EFTPOS Swiped

Switch to issuer

(domestic ‘rails’)

Scheme debit

Inserted/swiped

Contactless/card-not-present

Switch to acquirer

(scheme ‘rails’)

Open or closed credit

Swiped/inserted/contactless/card-

not-present

2.3.1 Proprietary EFTPOS cards

65. Proprietary EFTPOS is the traditional form of debit payment card used in New Zealand.

According to data provided to us by one of New Zealand’s switches, it has a current

market share of roughly 46 per cent of transactions (by volume). It was introduced in

New Zealand in 1984 as a series of separately run switches and trials, and was

progressively rolled out and consolidated through the 1980s.

6

The system was

developed by banks as a means of reducing the high cost associated with processing

cash and cheque payments, largely without government involvement. Cards are issued

by a consumer’s bank, and while Payments New Zealand maintains an interoperability

standard for EFTPOS, there is no ‘owner’ of EFTPOS as a product.

66. For reasons explored later in this Issues Paper – and in contrast to other countries such

as Australia and Canada – EFTPOS as a technology in New Zealand remains

fundamentally unchanged from when it was introduced in the 1980s. Payment

information is transmitted via a magnetic strip on an EFTPOS card, which is less secure

than other methods of electronic transmission of information. In addition, at present,

EFTPOS cards can only be used to pay for face-to-face transactions (card-present

6

Wilkinson, M. (2011). Development of Retail Payment Systems since 1949. Master’s Thesis. Retrieved

from http://hdl.handle.net/10063/1747

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

19

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

transactions), rather than online or over-the-phone sales (card-not-present

transactions). EFTPOS cards are also unable to be used for transactions made overseas.

67. Proprietary EFTPOS transactions are processed via a ‘switch to issuer’ model (domestic

rails – see Section 2.4).

2.3.2 Standard scheme debit cards

68. The first standard scheme debit card (named as such to distinguish it from contactless

scheme debit – see below) was introduced to New Zealand in 2006. The cards are issued

by a consumer’s bank using the technology and standards set by a card scheme – at

present, either Visa or MasterCard. In addition to a magnetic strip, scheme debit cards

also contain a chip that is inserted into a terminal, which provides greater security.

When inserted or swiped, scheme debit cards are currently processed under a ‘switch to

issuer’ model (discussed below) in the same way as proprietary EFTPOS, and funds are

accessed from the same bank account.

69. In addition to ‘card-present’ transactions, scheme debit cards can be also be used to pay

any merchant that accepts payments via the relevant scheme online, over the phone, or

overseas. In these instances, debit cards are ‘switched to acquirer’ (see below) process.

Scheme debit cards, when inserted or swiped, represent approximately 20 per cent of

transactions.

2.3.3 Contactless scheme debit

70. Since 2011, contactless debit cards (known as Visa PayWave and MasterCard PayPass)

have progressively entered circulation in New Zealand. In addition to inserting or

swiping a card, consumers have the option of ‘tapping’ their card against a terminal. This

allows payment for transactions below a threshold (currently $80, as set by Visa and

MasterCard) to be made contactlessly without the use of a PIN or signature.

71. When contactless functionality is used, scheme debit cards operate under a ‘switch to

acquirer’ model, even if the transaction exceeds the $80 limit and a PIN is required.

Swiping or inserting a contactless scheme debit card will see the transaction switched to

the issuer instead, in the same way that proprietary EFTPOS and standard scheme debit

transactions are processed. Contactless scheme debit is used for approximately 10 per

cent of transactions (but this share is rapidly growing).

2.3.4 Open credit card schemes

72. The first credit cards were introduced to New Zealand in the late 1970s. Open credit

card systems (often known as four-party systems) are the dominant form of credit card

system in New Zealand, and involve a card scheme (predominantly Visa and MasterCard)

working through issuers and acquirers (mainly banks) to attract consumers and

merchants to use and accept their product, respectively.

73. Open credit card schemes provide functionality similar to that of scheme debit cards,

with the obvious difference that they involve credit- rather than debit-based

transactions. It is the banks (as issuers), rather than card schemes, that provide

consumers with credit, and who guarantee the payment to merchants through their

acquirers. Open credit card systems are processed under a ‘switch to acquirer’ model

(see below).

74. Open credit cards have benefited from considerable investment and innovation on the

part of the schemes and banks. As a result of this, and significant marketing efforts

(discussed later), schemes have built an extensive international network of usage and

acceptance.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

20

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

75. Open credit cards often have contactless functionality but regardless of whether a credit

card is inserted, swiped or used contactlessly, the transaction is switched to the

acquirer. Open and closed (see below) credit cards are collectively used for

approximately 24 per cent of transactions.

2.3.5 Closed credit card schemes

76. The last major form of payment card is a closed credit card scheme (often known as a

three-party system). Under such a system, the scheme – such as American Express or

Diners Club – is also the issuer and acquirer of payment cards. That means that the

scheme directly works to attract consumers to use, and merchants to accept, their

payment cards. In addition, it is the scheme that is the provider of credit to a consumer.

77. Closed credit card schemes are processed under a ‘switch to acquirer’ model. We

understand that the market share of closed credit card schemes in New Zealand is

relatively low, at around 2 per cent of all card-based transactions.

Methods of switching 2.4

78. There are two main ways in which a card-based transaction can be processed, or

‘switched’: switch-to-issuer and switch-to-acquirer.

2.4.1 Switch to issuer (domestic rails)

79. When a proprietary EFTPOS card is used, or a scheme debit card is inserted or swiped,

the transaction is processed via a ‘switch to issuer’ model. Under this process:

• A switch sends the transaction details from the customer interface to the issuing

bank for authorisation.

• The issuing bank authorises or declines the transaction and returns the message to

the customer interface.

• The money is immediately debited (cleared) from the customer’s account at the time

it is authorised.

• Funds are settled between the cardholder’s and merchant’s financial institutions via

the inter-bank settlement process and deposited in the merchant’s account in a

lump-sum each day after inter-bank settlement.

2.4.2 Switch to acquirer (scheme rails)

80. A payment is processed using a ‘switch to acquirer’ model for all credit card

transactions, and for contactless, card-not-present, and international scheme debit

transactions. When this occurs:

• A transaction is switched from a customer interface to an acquirer (how it gets there

depends on the channel in which the transaction originates).

• The acquirer switches the transaction details to the card scheme.

• The scheme sends the authorisation request to the issuing bank.

• The issuing bank confirms whether the cardholder has sufficient available credit to

cover the purchase, and returns a response through the card scheme network, either

granting or denying authorisation.

• The acquirer receives the response and returns the message to the customer

interface.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

21

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

• The acquiring bank reconciles and transmits authorisations via the appropriate

scheme. Funds are deposited in a merchant’s account in a lump-sum after inter-bank

settlement, and debited from a customer’s balance in accordance with the relevant

scheme’s rules.

• Schemes settle funds with acquirers within 72 hours of the transaction occurring.

2.4.3 Variations

81. There are a number of variations to these two methods. These include cases where the

customer interface also acts as the switch, where the transaction bypasses a stand-alone

switch to be switched purely by a scheme, and when a transaction is processed by a self-

acquirer. These variations are not important for the purposes of this Issues Paper. As will

be discussed in Sections 3 and 4, what matters is whether a transaction passes through a

scheme – as all switch-to-acquirer transactions inherently do – since this determines the

business model under which the transaction takes place.

Trends in usage of payment options 2.5

82. In the year to March 2016, New Zealanders made more than 1.5 billion electronic card

transactions, representing more than $76 billion in expenditure. Transactions made

using electronic cards were responsible for 68.5 per cent of retail trade revenue in core

industries (excluding vehicle and fuel sales), an increase from 58.8 per cent in 2004 (see

Figure 1).

7

This means that the total share of other forms of payment (including cash,

cheques, bank transfers, and direct debits) is falling. In addition, the average value of

each electronic transaction is falling over time, reflecting the displacement of cash

(which is often used for low-value transactions).

Figure 1: Value of electronic card transactions as a percentage of total core retail

trade sales (Statistics New Zealand data)

83. Figure 2 shows that the split between credit and debit has remained relatively constant

since 2002.

8

7

Statistics New Zealand. (2016). Electronic Card Transactions. Retrieved from

http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/businesses/business_characteristics/electronic-card-

transactions-info-releases.aspx.

8

The slight upward trend in credit card usage in the last two years is misleading and represents the

miscategorisation of contactless debit transactions as credit transactions in the data provided to

Statistics New Zealand by New Zealand switches.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

%

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

22

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

Figure 2: Credit and debit card transactions as a percentage of electronic card

transactions (Statistics New Zealand data)

84. Even though the split between debit and credit spend has remained relatively constant,

there has been a notable shift in the types of transaction taking place over the last two

years, according to figures provided to us by one of New Zealand’s domestic switches.

Figure 3 (below) shows a significant decline in the value of transactions made with

proprietary EFTPOS cards, from around 44 per cent of card transactions in January 2014,

to 36 per cent in April 2016. There has also been a corresponding increase in the value

of contactless debit transactions, from 1 to 7 per cent of total transaction value. This has

taken the share of transactions that are processed via scheme rails from 40 to 49 per

cent of the transactions processed by this switch.

Figure 3: Value of electronic card transactions by card type (New Zealand switch

data)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

2002Q4

2003Q2

2003Q4

2004Q2

2004Q4

2005Q2

2005Q4

2006Q2

2006Q4

2007Q2

2007Q4

2008Q2

2008Q4

2009Q2

2009Q4

2010Q2

2010Q4

2011Q2

2011Q4

2012Q2

2012Q4

2013Q2

2013Q4

2014Q2

2014Q4

2015Q2

2015Q4

Credit card usage as a proportion of total electronic card transactions value

Debit card usage as a proportion of total electronic card transactions value

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Credit Card Credit Card (Contactless) Scheme Debit (Contactless)

Scheme Debit (Swipe/Insert) Proprietary EFTPOS

Switch to

acquirer

(scheme

rails)

Switch to

issuer

(domestic

rails)

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

23

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

85. Figure 4 provides the same transaction data, but by the number of transactions, rather

than their value. Switch-to-acquirer transactions form a lower proportion of this graph

than Figure 3, because the average value of credit card transactions is higher than for

other cards.

Figure 4: Number of electronic card transactions by card type (New Zealand switch

data)

Emerging payment methods 2.6

86. In addition to card-based payments, there are a number of other payment methods that

have been launched over the past few years, or are soon to be released. These can be

broken down into:

• Those that utilise existing scheme rails, which mean that a scheme debit or credit

card is required for payment.

• Those that do not rely on scheme rails. Many of these involve ‘direct entry’ to a

consumer’s bank account, otherwise known as a bank-to-bank transfer. While direct

entry methods are not new, the integration of them into a merchant’s point-of-sale

(POS) system is.

87. Payment methods can also be distinguished by whether they are used for card-present

or card-not-present (predominantly online) transactions, although over time this

distinction may blur.

88. Table 2 outlines many of these emerging methods.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Credit Card Credit Card (Contactless) Scheme Debit (Contactless)

Scheme Debit (Swipe/Insert) Proprietary EFTPOS

Switch to

acquirer

(scheme

rails)

Switch to

issuer

(domestic

rails)

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

24

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

Table 2: Types of emerging payment method

Name Rails Type of transaction Description

Apple Pay Scheme Card-present and

card-not-present

Contactless payment option that utilises

Apple devices instead of a card. Recently

launched in New Zealand for ANZ

customers. Utilises near-field

communication technology to enable

payment at any terminal where

contactless payments are accepted. In

addition, Apple Pay facilitates faster

payments within apps on Apple devices.

Android Pay Scheme Card-present and

card-not-present

Similar to Apple Pay, but for Android

devices. Not yet available in New

Zealand. Android Pay also facilitates

faster purchases within Android apps.

goMoney

wallet

Scheme Card-present Launched by ANZ in 2015. Similar to the

above, but operates from within the

existing ANZ mobile app on compatible

Android phones. GoMoney also supports

payments between ANZ accounts using a

cell phone number, so is also a direct

entry payment method in this respect.

Direct entry Card-not-present

ASB Virtual Scheme Card-present Similar to GoMoney wallet. ASB’s mobile

app also supports direct entry payment

through the use of cell phone numbers

or email addresses.

Direct entry Card-not-present

PayTag Scheme Card-present A sticker that a consumer attaches to

their phone (or anything else). This

utilises the same technology as that

contained in a contactless card. Offered

by ASB for Visa products, and Westpac

for MasterCard products.

PayPal Scheme or

direct entry

Card-not-present Allows consumers to pay for goods and

services online by entering their email

address and password. While generally

linked to a scheme card, a PayPal

account can also be funded through

direct entry methods. PayPal acts an

alternate acquirer for merchants who

may not have a relationship with an

acquiring bank.

MasterPass Scheme Card-not-present A digital wallet developed by MasterCard

that stores a consumer’s payment and

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

25

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

shipping information in one location. This

allows consumers to make faster online

payments with merchants that have

integrated MasterPass into their

payment gateway. Despite being

developed by MasterCard, it can also be

used with Visa, American Express and

Diners Club cards.

Visa

Checkout

Scheme Card-not-present Similar to MasterPass.

POLi Direct entry Card-not-present Introduced in New Zealand in 2009.

When paying via POLi at an online

checkout, a consumer selects their bank

and enters their internet banking details,

POLi populates the transaction details,

and the consumer confirms payment.

While a number of online merchants,

including Air New Zealand and the

Warehouse accept POLi, banks have

expressed concern that payment

methods like POLi expose consumers to

increased risk and could be in breach of

banks’ terms and conditions.

Account2

Account

Direct entry Card-not-present Operated by Payment Express. Similar to

POLi.

PayHere Direct entry Card-not-present Launched by ASB in 2013. Under this

system, any ASB customer can pay a

participating merchant by entering their

cell phone number in the merchant’s

payment gateway, and confirming the

payment via their ASB mobile app. No

bank account details are exchanged, and

transactions are processed instantly.

Because PayHere sits within a merchant

gateway, businesses do not need to have

a banking relationship with ASB to accept

PayHere payments. Merchant

acceptance of PayHere appears to be

relatively low.

89. In addition, we understand that Paymark is in the process of finalising its own online

EFTPOS solution, which works similarly to PayHere.

90. Many of the above scheme-based methods utilise what is known as ‘tokenisation’. This

supports greater security – rather than providing the scheme card number to the

terminal, the terminal receives a device-specific ‘token’ and a one-use-only security

code. The token is translated into a credit card number only when it reaches the

scheme, meaning that only the scheme and the issuer have information about both the

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

26

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

person and the transaction. Tokenisation also avoids the technical limitations that can

be associated with the unique card number on a physical card.

91. Crucially, other than switch-to-issuer transactions, there are not currently any

mainstream electronic payment methods in New Zealand that facilitate direct entry for

store-based (i.e. card-present) transactions. However, we are aware of industry

participants that are exploring options around the development of payment methods

that bypass scheme infrastructure through the use of:

• Blockchain – a digital ledger that records transactions which resides not on a single

server, but across a distributed network of computers. Ripple is a company that

utilises a distributed ledger process to enable participants to directly transact with

each other in real time, without the need for a central counterparty. The widespread

applicability of this technology to retail payments is seemingly some time away, but

should not be discounted.

• Application programme interfaces (APIs) – sets of routines, protocols, and tools for

building software applications. These have the potential to make it easier for industry

to offer bank-to-bank payment solutions that build off a common set of

infrastructure. For example, if banks allowed APIs to access their internet banking

platforms, it would allow non-banks to develop payment products over the top of the

issuer-customer banking relationship. The European Union’s revised Directive on

Payment Services (PSD2) is an example of an attempt by government to stimulate

competition in payments by allowing authorised third parties to use a consumer’s

bank details to make payments from their account.

2

Are there any other emerging payment methods that we have missed? If so, what is their

likely impact on the market?

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

27

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

3. Market business models and

resource costs

93. The previous section described, at a basic level, how retail payments are processed

between parties. This section builds on that by describing the flows of fees and

inducements under the various business models operating in New Zealand.

94. First, we introduce the business model underpinning switch-to-issuer transactions,

which is relatively straightforward. We then move onto describing the interchange

business model that underpins switch-to-acquirer transactions. This is a complex set of

relationships that drives the uptake of each product as well as the market share of

various products. In particular, we focus on the following four relationships:

• Card issuers (generally banks) and consumers.

• Issuers and acquirers (and the flow of interchange fees).

• Acquirers (generally banks) and merchants (and the payment of merchant service

fees, MSFs).

• Consumers and merchants (and the use of surcharging and steering).

Switch-to issuer transactions 3.1

3.1.1 Overview

95. Very little flows in the way of fees and charges when it comes to transactions that are

switched to the issuer (run on domestic rails), including all payments made on

proprietary EFTPOS cards and inserted and swiped transactions made on scheme debit

cards.

96. Charges to cardholders for switch-to-issuer transactions are rare, and the marginal cost

of these transactions to merchants is zero. While merchants do face fixed costs for

terminal hire and the per-terminal cost of being connected to a switch, these costs are

carried by all merchants that take electronic card payments, regardless of which

payment types they accept. We therefore refer to switch-to-issuer transactions as being

“free” to merchants for the remainder of this Issues Paper.

97. As a result, the cost to banks of processing these transactions is met from other bank

income sources. A key (but still relatively small) cost of processing switch-to-issuer

transactions is the cost of switching itself, a function provided by Paymark and Verifone

for these transactions. The issuing bank pays these switching costs.

98. Figure 5 below shows the flows of fees and inducements that underlie the relationship

between different parties for switch-to-issuer transactions. Some of these flows are only

applicable in certain situations. The majority of the lines in the diagram are dashed,

which represents the fact that the flows of funds are not substantial in respect of switch-

to-issuer transactions.

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

28

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

Figure 5: Fees and inducements in switch-to-issuer transactions

3.1.2 Customer-issuer relationships

99. It is important to see issuing banks’ competition for debit payment products as part of

their broader competition for personal banking consumers. This is because debit cards

are tied to a customer’s current account and a customer usually has their current

account with the bank that provides the remainder of their more significant banking

services (for example, their mortgage). This contrasts with credit cards, where it is more

common for someone to take out a credit card with a different bank to the one that

provides their other personal banking services.

100. There are flows of funds in both directions between customers and issuers related to

the maintenance of transactional bank accounts:

• Account fees, transaction fees and card fees that are paid from the customer to the

issuer.

• Interest, and occasionally rewards, that are paid to the customer by the issuer.

101. It is difficult to separate the flows relating to the operation of the account from flows

relating to the use of the payment functionality of a proprietary EFTPOS or scheme debit

card. Nevertheless, in general, banks do not charge consumers to use proprietary

EFTPOS or scheme debit cards, although some current accounts do attract a low

monthly fee that contributes to the overall cost of running the account. Per-transaction

fees were common when EFTPOS was introduced but over time they have been largely

competed away for most account types. Some banks also charge consumers a low

annual fee for a scheme debit card.

102. We have been advised that these charges do not fully offset the cost of providing these

debit payment options. Therefore, these costs are generally partially funded by banks

through other mechanisms, such as reduced interest payments to consumers on debit

balances (and interchange fees when the card is used contactlessly).

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

29

Retail Payment Systems in New Zealand: Issues Paper

103. Table 3 presents four (relatively representative) account types – tied to scheme debit

cards – that were available in January 2016.

Table 3: Examples of scheme debit fees, interest and rewards as at January 2016

(public data)

BNZ YouMoney

FlexiDebit Visa

ASB Omni

Westpac Access

Airpoints Debit

MasterCard

TSB Personal Visa

Debit

Account fee

$5/month

$0

$3.50/month

$0

Transaction

fee

$0

$0.40/transaction

$0

$0

Card fee

$10.00 p.a.

$10.00 p.a.

$15.00 p.a.

$10.00 p.a.

Interest rate

(on savings)

0% p.a.

0% p.a.

0% p.a.

1.00% p.a. on

balances above $500;

1.50% p.a. on

balances above

$10,000.

Rewards

NA.

NA.

1 Airpoint per $250

spent.

NA.

104. There are generally no inducements to use proprietary EFTPOS or scheme debit cards.