(

PB98-916401

NTSB/MAR-98/01

NATIONAL

TRANSPORTATION

SAFETY

BOARD

WASHINGTON,

D.C.

20594

MARINE ACCIDENT REPORT

ALLISION OF THE LIBERIAN FREIGHTER

BRIGHT

FIELD WITH THE POYDRAS STREET

WHARF, RIVERWALK MARKETPLACE, AND

NEW ORLEANS HILTON HOTEL IN

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA

DECEMBER 14, 1996

E!!!k!d

P

.,

‘e.

:--9

-Q

.

‘

‘..

—.

-.

–—

—’””

6885A

\

U S

GOWRNMEhl

PRINT!%

OFFICE

IW

0+4!4s

Abstract: On December 14, 1996, the fully loaded Liberian bulk carrier Bright Field

temporarily lost propulsion power as the vessel was navigating outbound in the Lower

Mississippi River at New Orleans, Louisiana. The vessel struck a wharf adjacent to a populated

commercial area that included a shopping mall, a condominium parking garage, and a hotel. No

fatalities resulted from the accident, and no one aboard the Bright Field was injured; however, 4

serious injuries and 58 minor injuries were sustained during evacuations of shore facilities, a

gaming vessel, and an excursion vessel located near the impact area. Total property damages to

the Bright Field and to shoreside facilities were estimated at about $20 million.

The safety issues discussed in this report are the adequacy of the ship’s main engine and

automation systems, the adequacy of emergency preparedness and evacuation plans of vessels

moored in the Poydras Street wharf area, and the adequacy of port risk assessment for activities

within the Port of New Orleans. This report also addresses three other issues: the actions of the

pilot and crew during the emergency, the lack of effective communication (as it relates to the

actions of the pilot and crew aboard the Bright Field on the day of the accident), and the delay in

administering toxicological tests to the vessel crew.

As a result of its investigation, the National Transportation Safety Board issued

recommendations to the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the State of

Louisiana, the Board of Commissioners of the Port of New Orleans, International RiverCenter,

Clearsky Shipping Company, New Orleans Paddlewheels, Inc., the New Orleans Baton Rouge

Steamship Pilots Association, the Crescent River Port Pilots Association, and Associated Federal

Pilots and Docking Masters of Louisiana, Inc.

The National Transportation Safety Board is an independent Federal agency dedicated to

promoting aviation, railroad, highway, marine, pipeline, and hazardous materials safety. Established

in 1967, the agency is mandated by Congress through the Independent Safety Board Act of 1974 to

investigate transportation accidents, determine the probable causes of the accidents, issue safety

recommendations, study transportation safety issues, and evaluate the safety effectiveness of

government agencies involved in transportation. The Safety Board makes public its actions and

decisions through accident reports, safety studies, special investigation reports, safety

recommendations, and statistical reviews.

Information about available publications may be obtained by contacting:

National Transportation Safety Board

Public Inquiries Section, RE-51

490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W.

Washington, D.C. 20594

(202) 314-6551

Safety Board publications may be purchased, by individual copy or by subscription, from:

National Technical Information Service

5285 Port Royal Road

Springfield, Virginia 22161

(703) 605-6000

#..+5+10"1("6*'".+$'4+#0"(4'+)*6'4

$4+)*6"(+'.&"9+6*"6*'"21;&4#5"564''6

9*#4(."4+8'49#.-"/#4-'62.#%'."#0&

0'9"14.'#05"*+.610 "*16'."+0

0'9"14.'#05.".17+5+#0#

&'%'/$'4"36."3;;8

MARINE ACCIDENT REPORT

Adopted: January 13, 1998

Notation 6885A

0#6+10#.

64#052146#6+10

5#('6;"$1#4&

9CUJKPIVQP."&0%0"427;6

this page intentionally left blank

iii

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.........................................................................................................vii

INVESTIGATION

Synopsis .......................................................................................................................................... 1

Preaccident Events ..........................................................................................................................1

The Accident ................................................................................................................................... 5

Injuries...........................................................................................................................................10

Vessel Damage..............................................................................................................................10

Other Damage................................................................................................................................ 10

Crew Information .......................................................................................................................... 14

The Pilot................................................................................................................................. 14

The Master ............................................................................................................................. 14

The Chief Engineer................................................................................................................16

The Previous Chief Engineer................................................................................................. 17

Vessel Information ........................................................................................................................ 17

Bright Field............................................................................................................................ 17

Automated Propulsion Control System ..........................................................................18

Engine Lubricating Oil System.......................................................................................19

Cruise Ships ........................................................................................................................... 20

Gaming and Excursion Vessels.............................................................................................. 20

Waterway Information................................................................................................................... 21

River Stage............................................................................................................................. 21

Vessel Traffic Control............................................................................................................ 21

Port Information............................................................................................................................ 22

Dredging................................................................................................................................. 22

The Wharf Area...................................................................................................................... 23

Federal Jurisdiction................................................................................................................23

Meteorological Information ..........................................................................................................25

Toxicological Information.............................................................................................................25

Survival Aspects............................................................................................................................ 26

Bright Field............................................................................................................................ 26

Enchanted Isle........................................................................................................................26

Nieuw Amsterdam.................................................................................................................. 26

Queen of New Orleans...........................................................................................................27

Creole Queen ......................................................................................................................... 30

Riverwalk Marketplace..........................................................................................................32

Hilton Riverside Hotel ...........................................................................................................33

Emergency Response.....................................................................................................................34

Port of New Orleans Harbor Police ....................................................................................... 34

Coast Guard Group New Orleans ..........................................................................................35

Louisiana Office of Emergency Preparedness .......................................................................35

iv

Police Departments ................................................................................................................35

New Orleans Fire Department ...............................................................................................35

New Orleans Department of Health and Emergency Medical Services................................. 35

Emergency Preparedness...............................................................................................................36

Riverwalk Marketplace..........................................................................................................36

New Orleans Hilton Riverside Hotel ..................................................................................... 36

Queen of New Orleans...........................................................................................................36

Safety Briefings............................................................................................................... 37

Signage............................................................................................................................ 37

Emergency Egress........................................................................................................... 37

Drills ............................................................................................................................... 38

Creole Queen ......................................................................................................................... 38

Inspections, Tests, and Research...................................................................................................38

Steering Gear.......................................................................................................................... 39

Main Engine—General .......................................................................................................... 39

Main Engine Lubricating Oil Sump.......................................................................................39

Main Engine Lubricating Oil Pumps/Motors......................................................................... 39

Main Engine Lubricating Oil System Second Filter/Strainer ................................................40

Main Engine Lubricating Oil Purifier.................................................................................... 40

Automatic Main Engine Lubricating Oil Trip Function ........................................................41

Alarms, Indicators, and Recorders.........................................................................................41

Remote Engine Control Tests ................................................................................................41

Preventive Maintenance.........................................................................................................41

Reports and Recordkeeping ................................................................................................... 41

Main Engine Lubricating Oil Testing and Analysis............................................................... 42

Spare Parts and Calibration Tools.......................................................................................... 42

Sulzer Inspection....................................................................................................................42

Chief Engineer’s Assessment................................................................................................. 43

Tests, Reports, and System Calibration ................................................................................. 43

Computer Simulation.............................................................................................................44

Other Information..........................................................................................................................44

Port Risk Analysis and Management—Coast Guard............................................................. 44

Port Risk Analysis and Management—Other Stakeholders .................................................. 45

Lower Mississippi River Safety Study............................................................................ 45

Louisiana World Exposition........................................................................................... 45

International RiverCenter................................................................................................ 46

New Orleans Aquarium of the Americas........................................................................ 46

Gaming Vessel Risks and Background........................................................................... 47

Operation Safe River....................................................................................................... 50

Changes Made Since the Accident......................................................................................... 51

River Front Alert Network.............................................................................................. 51

New Notices, Rules, and Operating Regulations............................................................ 51

Steering Loss Study ........................................................................................................ 53

Ship Drill Alarms............................................................................................................ 53

Riverwalk Marketplace Alert System............................................................................. 53

v

Vessel Egress..................................................................................................................54

Status of the Queen of New Orleans...............................................................................54

General .......................................................................................................................................... 55

ANALYSIS

Accident Overview........................................................................................................................55

Engineering Aspects......................................................................................................................56

Main Engine Shutdown and Restart....................................................................................... 56

Lubricating Oil Pump Operation............................................................................................ 57

General Condition of the Bright Field’s Engineering Plant................................................... 57

Vessel Owner’s Oversight of the Bright Field’s Engineering Plant...................................... 58

Communication............................................................................................................................. 59

Master-Pilot Briefing at the Anchorage .................................................................................59

Language Differences............................................................................................................. 60

Information Exchange During the Emergency....................................................................... 60

Emergency Response.....................................................................................................................62

Vessel Emergency Preparedness and Evacuation Plans................................................................ 63

Vessel Evacuation..................................................................................................................63

Emergency Drills....................................................................................................................65

Safety Briefings and Signage.................................................................................................66

Shoreside Emergency Alert and Response............................................................................. 67

Toxicological Testing.................................................................................................................... 68

Risk Assessment and Risk Management....................................................................................... 69

Findings......................................................................................................................................... 75

CONCLUSIONS

Findings......................................................................................................................................... 74

Probable Cause.............................................................................................................................. 76

RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................................ 77

APPENDIXES

APPENDIX A--Investigation........................................................................................................81

APPENDIX B--Chronology of Bright Field Engineering Problems ............................................ 83

APPENDIX C--Voyage Data Recorders (VDRs) .........................................................................89

this page intentionally left blank

vii

Shortly after 1400 on December 14, 1996,

the fully loaded Liberian bulk carrier

Bright

Field

temporarily lost propulsion power as the

vessel was navigating outbound in the Lower

Mississippi River at New Orleans, Louisiana.

The vessel struck a wharf adjacent to a

populated commercial area that included a

shopping mall, a condominium parking garage,

and a hotel. No fatalities resulted from the

accident, and no one aboard the

Bright Field

was injured; however, 4 serious injuries and 58

minor injuries were sustained during

evacuations of shore facilities, a gaming vessel,

and an excursion vessel located near the impact

area. Total property damages to the

Bright Field

and to shoreside facilities were estimated at

about $20 million.

The National Transportation Safety Board

determines that the probable cause of this

accident was the failure of Clearsky Shipping

Company to adequately manage and oversee the

maintenance of the engineering plant aboard the

Bright Field

, with the result that the vessel

temporarily lost power while navigating a high-

risk area of the Mississippi River. Contributing

to the amount of property damage and the

number and types of injuries sustained during

the accident was the failure of the U.S. Coast

Guard, the Board of Commissioners of the Port

of New Orleans, and International RiverCenter

to adequately assess, manage, or mitigate the

risks associated with locating unprotected

commercial enterprises in areas vulnerable to

vessel strikes.

The major safety issues identified in this

investigation are the adequacy of the ship’s

main engine and automation systems, the

adequacy of emergency preparedness and

evacuation plans of vessels moored in the

Poydras Street wharf area, and the adequacy of

port risk assessment for activities within the

Port of New Orleans. This report also addresses

three other issues: the actions of the pilot and

crew during the emergency, the lack of effective

communication (as it relates to the actions of the

pilot and crew aboard the

Bright Field

on the

day of the accident), and the delay in

administering toxicological tests to the vessel

crew.

As a result of its investigation of this

accident, the Safety Board issued safety

recommendations to the U.S. Coast Guard, the

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the State of

Louisiana, the Board of Commissioners of the

Port of New Orleans, International RiverCenter,

Clearsky Shipping Company, New Orleans

Paddlewheels, Inc., the New Orleans Baton

Rouge Steamship Pilots Association, the

Crescent River Port Pilots Association, and

Associated Federal Pilots and Docking Masters

of Louisiana, Inc.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

this page intentionally left blank

1

Synopsis

Shortly after 1400 on December 14, 1996,

the fully loaded Liberian bulk carrier

Bright

Field

temporarily lost propulsion power as the

vessel was navigating outbound in the Lower

Mississippi River at New Orleans, Louisiana.

The vessel struck a wharf adjacent to a

populated commercial area that included a

shopping mall, a condominium parking garage,

and a hotel. No fatalities resulted from the

accident, and no one aboard the

Bright Field

was injured; however, 4 serious injuries and 58

minor injuries were sustained during

evacuations of shore facilities, a gaming vessel,

and an excursion vessel located near the impact

area. Total property damages to the

Bright Field

and to shoreside facilities were estimated at

about $20 million.

Preaccident Events

According to vessel records, on September 2,

1996, the 735-foot, 36,120 gross-ton

Bright Field

completed loading a cargo of coal in

Banjarmasin, Indonesia. On September 12, 1996,

the vessel departed Indonesia with a 28-member

Chinese crew bound for Davant, Louisiana. The

estimated date of arrival at Southwest Pass,

Louisiana,

1

(the vessel’s entrance point to the

Mississippi River) was October 26, 1996. Shortly

after departure, the ship began to experience

problems with its engineering plant, necessitating

a 3-day layover in Singapore while repairs were

made to the main engine. After the repairs were

completed, the

Bright Field

continued its voyage.

The trip was interrupted on several occasions by

continuing main engine problems.

On November 21, 1996, the

Bright Field

arrived at a bulk coal-handling facility near

Davant, Louisiana (mile 55 AHP

2

), where it

1

Southwest Pass is the westernmost of the several

entrances to the Mississippi River and is the one most often

used.

2

Distances in the Mississippi River are measured in

statute miles “above head of passes” (AHP), which is

located 20 miles above Southwest Pass.

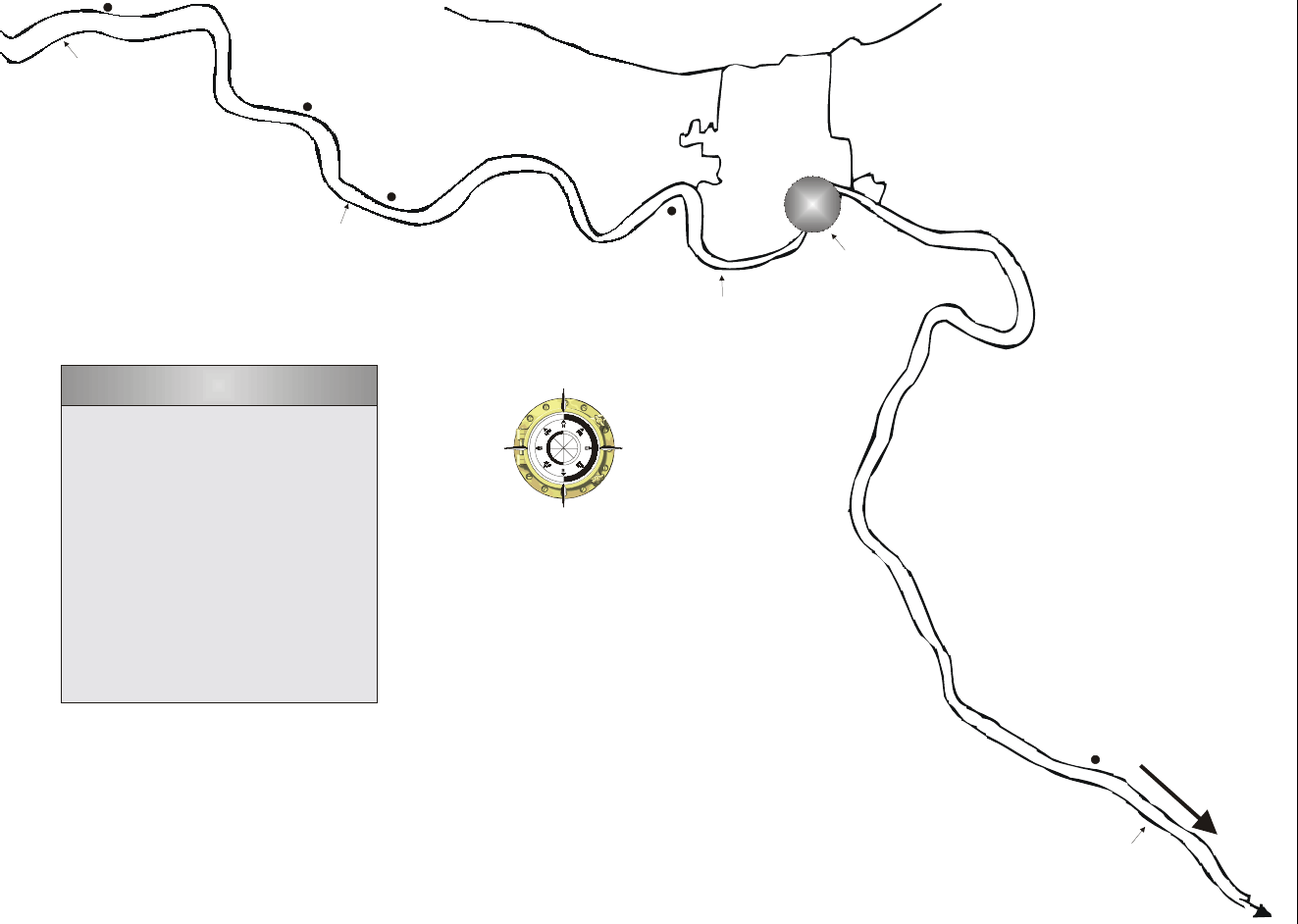

unloaded its cargo. (See figure 1.) After its holds

were prepared to load grain and after waiting for

a loading berth, the

Bright Field

arrived at

Cargill Terminal, located at mile 140 AHP in

Reserve, Louisiana, on December 9, 1996.

There the vessel loaded 56,397 metric tons of

corn in its seven cargo holds. The vessel left the

terminal at 1530 on December 11, 1996.

3

The

vessel moved from the terminal area to the

lower portion of La Place Anchorage at mile

135 AHP, where it remained at anchor for 2

days while scheduled repairs were made to the

main engine’s turbocharger and air cooler.

On December 14, 1996, the vessel’s agent

contacted the New Orleans Baton Rouge

Steamship Pilots Association (NOBRA) and

requested that a pilot be dispatched to the vessel.

4

The sailing time was set for 1030. The pilot who

was dispatched to the

Bright Field

stated that he

was called for duty about 0730. He said he was

told that the ship was headed to sea, which

meant that he would take the ship to a specified

location, where he would be replaced by a pilot

from the Crescent River Port Pilots Association

for the remainder of the trip downriver. The

pilot said he expected to be aboard the

Bright

Field

for about 3 hours.

The

Bright Field

third mate and chief

electrician stated that on the morning of

December 14 they completed all predeparture

tests for both bridge and engineering, including

testing the bridge main engine console lights and

alarms. With the successful completion of the

tests, the master ordered standby engines at 0943.

The pilot boarded the vessel via launch at 1040,

3

At the time of departure, the draft of the vessel was

11.96 meters (about 39 feet 4 inches) forward and 12.06

meters (about 39 feet 8 inches) aft.

4

Louisiana State law requires that a qualified and

certified State pilot be on board any vessel in foreign trade

navigating the Mississippi River in the State. Although

NOBRA, as well as other pilot associations, dispatches

pilots, bills and collects pilotage fees, and pays association

expenses, including staff and transportation fees, the pilots

themselves are self-employed and contract for their services

directly with vessel operators.

INVESTIGATION

2

N

0LOH

473

0LOH

453

0LOH

433

0LOH

<8

0LOH

83

7

R#

*

XO

I#

RI

0H[LFR#

D

Q

G

+

H

DG#R

I

#3D

VV

H

V

/$.(#3217&+$575$,1

1(:

25/($16

#

$

%

&

'

:

#

$

%

&

'

:

0#5HVHUYH

0#1RUFR

0#'HVWUHKDQ

0#1LQH#0LOH#3RLQW

0#'DYDQW

0#$FFLGHQW#6LWH

/RFDWLRQ#/HJHQG

Figure 1 -- Lower Mississippi River

3

and the third mate escorted him to the

wheelhouse, where he was introduced to the

master at 1044.

The ship’s master spoke what the pilot

described as broken, but adequate, English. The

pilot said that, to facilitate communication, he

spoke slowly and used simple words, and he

believed that he and the master understood each

other. The master also stated that he was

satisfied with their ability to communicate. The

pilot said he gave helm orders in English to the

helmsman, who repeated them in English before

carrying them out. The second mate reported

that he also repeated (in English) the pilot’s

orders and then carried them out. Other than

orders and their repetition, the pilot said he had

no verbal exchanges with the second mate or the

helmsman.

The pilot, who had not previously handled

the

Bright Field

, said he asked if the ship’s

navigational equipment and engine were in good

working order. He stated that the master

answered with “just a simple ‘yes’ to both

questions.” The master stated that he asked the

pilot about the operational procedures for

departing the anchorage.

5

These were the only

items reported as being discussed during the

predeparture briefing. The pilot said he then

proceeded to acquaint himself with the

wheelhouse layout (figure 2) and with the

vessel’s posted maneuvering information. At the

time, the vessel’s main engine was being

operated from the wheelhouse.

At 1055,

6

the pilot began the normal

procedures for getting underway by ordering the

first engineering maneuvering bell (dead slow

ahead). According to the third mate, he (the

third mate) attempted to execute the pilot’s

order using the wheelhouse engine controls, but

the vessel’s main engine did not start. He then

called the engine control room and told the chief

engineer—in Chinese—that the engine did not

start. Engine control was transferred to the

engine control room. Both the master and the

chief engineer stated that their normal practice

5

This information typically includes, among other

details, the location of assist tugboats and the order in

which the two anchors are to be raised.

6

Times are taken from engine bell logs.

was to transfer engine control to the engine

control room in the event of a nonemergency

problem with the propulsion system.

After the engines were started (1055.5, dead

slow ahead), engine control was transferred

back to the wheelhouse. The pilot ordered stop

engine, and the engine was stopped. At 1110,

the pilot ordered dead slow ahead. Again, the

engine could not be started from the

wheelhouse, and again control was transferred

to the engine control room, from which the

engine was restarted. After the accident, the

pilot stated that he had not been advised of the

difficulties in starting the engine from the

wheelhouse, nor was he informed on those

occasions when engine control was transferred

to or from the engine control room.

The

Bright Field

departed the La Place

anchorage at 1112. Engine maneuvering control

was transferred back to the wheelhouse, and the

pilot ordered full ahead maneuvering speed (56

rpm) in order to familiarize himself with the

ship’s responsiveness to rudder and engine

orders. He said he determined that the

Bright

Field

handled as expected for a fully loaded

bulk cargo vessel operating in high-river-stage

conditions.

7

At 1134, the pilot ordered sea speed

(72 rpm) for better ship handling. The pilot said

it was necessary to operate the ship at maximum

speed in order to obtain the best maneuverability

in that operating environment.

Engine rpm was increased to sea speed

using wheelhouse controls. At 1159, as the

vessel approached Norco, Louisiana, the pilot

ordered the

Bright Field’

s

speed reduced to full

ahead maneuvering speed (56 rpm). The

Bright

Field

remained at full ahead maneuvering speed

until it reached the vicinity of Destrehan,

Louisiana, when the pilot again ordered sea

speed of 72 rpm, resulting in a ground speed

(speed of the ship plus speed of the current) of

about 16 knots.

About 1300, the pilot ordered the master to

send a seaman to stand by the anchors.

8

The

7

On the day of the accident, the river was at high river

stage, measuring 12.5 feet on the Carrollton gauge with an

approximate 4 1/2-mph current.

8

A Board of Commissioners of the Port of New

Orleans ordinance required that all vessels navigating

4

master sent the ship’s carpenter, with a handheld

radio, to serve as anchor watch.

9

A few miles

above Nine Mile Point, the pilot established

VHF communications

10

with an inbound tow

and inbound ship, both below Nine Mile Point.

The vessels agreed to a starboard-to-starboard

meeting, and all three vessels met at the point.

The pilot of the

Bright Field

said that, because

the inbound tow was farther off the bank than

anticipated, he maneuvered his ship

closer to the

left descending bank of the river. The

Bright

through the New Orleans Port area maintain an anchor

standby of at least one competent seaman, who was to be

stationed at the anchor windless and be prepared to drop

anchor if necessary.

9

Serving as anchor watch was a regularly assigned

duty of the

Bright Field

’s carpenter.

10

VHF channel 67 was assigned for routine bridge-to-

bridge (navigation/safety) communication in the Lower

Mississippi River.

Field

pilot sounded the danger signal

11

to alert

the workers at the Southport barge fleeting

facility

12

to the proximity of the

Bright Field

.

The

Bright Field

passed the area without

incident and continued down the river at sea

speed. The master told Safety Board

investigators that about this time he became

concerned that the pilot might be oversteering

the vessel, but he said he did not voice his

concerns to the pilot.

About 1350, the pilot made the first radio

call to the U.S. Coast Guard Gretna light

operator.

13

The Gretna light operator advised the

11

Five or more shorts blasts on the ship’s whistle.

12

A

fleet

in this instance refers to one or more tiers of

barges. A fleeting facility is the geographic area along or

near a river bank where a barge mooring service is located.

13

According to 33

Code of Federal Regulations

(CFR)

161.402(b), “Movements of vessels in vicinity of Algiers

Point, New Orleans Harbor,” during a high river stage,

1$9,*$7,21

(48,30(17

&+$57

7$%/(

5$'$5

2$53$

72#/2:(5

'(&.6

+(/060$1

+$/$50#/,*+762

7(/(3+21(6,

5$'$5

+(/0

*<52

3,/27

:,1'2:6#+8,

:+,67/(

&21752/

%87721

0$67(5

3257

%5,'* (

:,1*

:,1'2:6

6(&21'

0$7(

0$18(9(5,1*

/(9(52(1*,1(

25'(5

7(/(*5$3+

:2+#(1*,1(

&21752/#&2162/(

67$5%2$5'

%5,'* (

:,1*

$)7

):

'

Figure 2 -- navigation bridge layout

Bri

g

ht Field

5

Bright Field

that the ship was cleared to transit

Algiers Point and that a seagoing tow boat was

inbound at the Point. The pilot stated that, while

the

Bright Field

was transiting under the

Crescent City Connection Bridges, he allowed

the vessel to acquire a current-induced swing to

port to facilitate the upcoming maneuver around

Algiers Point.

The Accident

The swing to port as the ship passed under

the Crescent City Connection Bridges pointed

the vessel toward the left descending bank, the

side of the river where the Poydras Street wharf

and the Riverwalk Marketplace shopping mall

were located and where gaming, excursion, and

cruise ships were docked. About 1406, while the

Bright Field

was still transiting under the

bridges, power output from the vessel’s main

engine dropped. At this time, the vessel’s

automated propulsion control system

14

reported

low main engine lubricating oil pressure and

main engine trip due to low oil pressure.

15

The pilot said he noticed that the vessel had

gotten quiet and that the engine-induced vessel

vibrations had stopped. He said he turned and

saw the master and the second mate

16

standing

beside the engine order telegraph (on the other

side of the bridge from the pilot), looking down

at something on the console. He said he asked

them if there was a problem, but got no

response. He said that he did not ask a second

time “because they didn’t answer me the first

time.” He reported that he then looked at the

engine rpm indicator and saw that engine rpm

movement of vessels around Algiers Point is controlled by

several Coast Guard-operated and maintained traffic lights,

including Gretna light at 96.6 miles AHP and Governor

Nicholls light at 94.3 AHP.

14

For the purposes of this report,

automated

propulsion control system

and related terms will be used to

refer to all main engine control, monitoring, and alarm

systems and subsystems.

15

The main engine was equipped with protection

devices that could slow down or stop the main engine

depending on the severity of the problem. See the “Main

Engine Description” section of this report for information

about the engine and its protective devices.

16

The second mate had come on duty at the noon

watch to replace the third mate who had been on duty when

the ship left the anchorage.

had dropped from about 70 to about 30,

indicating to him that the vessel had experienced

a significant reduction in engine power.

The master and the second mate said that

they also noticed that the ship’s normal operating

vibrations had stopped, and they observed that the

main engine rpm indicator showed a drop to

about 30 rpm. The master said the pilot “blurted

out, ‘What has happened?’” and he (the master)

thought he had answered the pilot by saying

there had been a reduction in main engine

power. The master said it was not clear to him

why engine rpm had dropped. He said he

instructed the second mate “to call the

engineroom to inquire about what happened,

what’s going on. I asked the second mate to

demand them to increase speed right away.” The

second mate said that he carried out the master’s

order immediately.

The pilot stated that when he realized that the

vessel had lost power, he “jumped” out of his

chair and called the Governor Nicholls Light

operator on VHF channel 67. He said that as he

made the call he was looking out the bridge

windows and was aware that the vessel was

swinging to port and toward the docked ships

along the left descending bank. The pilot told the

Governor Nicholls light operator that his ship had

lost power and that the operator should alert

everyone in the harbor.

17

The pilot said that, after calling the light

operator, he ordered hard starboard rudder as the

ship continued to swing to port. The helmsman

responded to the order by applying hard

starboard rudder, but the new rudder setting did

nothing to alter the vessel’s direction, and the

pilot began sounding the danger signal using the

ship’s forward whistle. He said he wanted to

attract the attention of the cruise ships and

public along the left descending river bank. The

pilot stated that he ordered the master on at least

two occasions to have someone stand by the

17

Information regarding radio transmissions using

VHF channel 67 is based on audio recordings made by the

tugboat

Lockmaster

, located on the side of the river

opposite the Poydras Street wharf. The

Lockmaster

was

also able to provide a videotape of radar images of the

Bright Field

as it approached and struck the wharf. The

traffic light stations were not equipped to record radio

transmissions.

6

anchors, but he did not hear the master

acknowledge the order. The pilot said he recalled

the master speaking Chinese on the radio and

that the master did not appear to be agitated, but

was “very nonchalant.”

When the pilot noted that the rpm indicator

continued to show a loss of power, he made

another call to the Governor Nicholls light

operator. He told the operator to warn the cruise

ships and gaming and excursion vessels that

were moored along the left descending bank.

The Gretna light operator advised the pilot that a

tugboat 1 mile upriver was coming to his aid.

The chief engineer on duty in the engine

control room

18

(figure 3) stated that,

immediately before the engine lost power, an

audible alarm sounded. He said he then looked

at a computer screen in front of him and saw a

visual alarm and an indication of a loss of

pressure in the lubricating oil system. (See

figure 4.) He said he looked at the analog main

engine lubricating oil pressure gauge and saw

that the system was rapidly “depressurizing”

below normal levels. He said he then noticed

that the main engine automatic slow down light

was on, and he noticed that main engine noise

was decreasing. He reported that he also

observed that engine rpm had dropped from 72

to between 30 and 35. He said that, as he turned

to the electrical switchboard behind him to

determine why the No. 2 lubricating oil pump

had not started automatically, the pump started.

He said that, except for the low rpm, everything

seemed to him to be back to normal almost

immediately.

According to the chief engineer, he was

about to call the bridge when the second mate

called him. He said that the second mate asked

him why the main engine was slowing down and

told him to increase the speed immediately, that

they were transiting the bridge at that time. The

chief engineer reported that the second mate

spoke to him in a normal tone of voice, without

18

At the time of the accident, Coast Guard regulations

did not require that engineering spaces be manned during

transit of the Mississippi River. Although the

Bright Field

was classed for unattended operation of machinery spaces,

company regulations required that the chief engineer and

two other engineers be on duty in the engine control room

whenever the vessel was entering or leaving a port.

repeating his message. The chief engineer said

he thought the second mate was concerned

about speeding up passage of the vessel beneath

the bridges. He said he did not know the nature

of the situation on the vessel’s bridge.

The chief engineer told the second mate that

he did not know the reason for the sudden drop

in the No. 1 oil pump pressure, but since the No.

2 pump had already come on line, the

pressurization problem was solved. Neither the

master nor the second mate attempted to clear

the trip condition and restart the engine, and

thus restore rpm, from the bridge controls. The

chief engineer and the second mate mutually

agreed to transfer engine control to the engine

control room, and the chief engineer began the

process of restoring engine power. He said that

engine rpm quickly reached about 52 rpm, after

which rpm continued to increase to about 60.

According to alarm logs, main engine power

was restored to the vessel at 1408, about 2

minutes after the logs indicated that the main

engine had tripped.

In postaccident testimony, the master was

asked if it had been necessary to transfer engine

control from the bridge to the engine control

room during the emergency. He said, “Under

normal circumstances, speed increase can be

done from the engine [control room] more

quickly.” The master was asked why the engine

control room had requested that engine control

be shifted from the bridge to the engineroom.

He said that it was “because the engineering

department [didn’t] realize the sense of urgency

or [that] there [was] any sense of urgency on the

bridge.” He said engine control room personnel

were not initially notified of the emergency

situation but were told later when the allision

19

was unavoidable even if vessel speed were

increased.

The pilot stated that at this time he was

devoting his attention to sounding the danger

signal to alert the moored ships along the left

descending bank and the Riverwalk complex

and that he was not immediately aware, nor was

19

In marine usage,

allision

refers to a moving ship

striking a stationary ship or other stationary object.

7

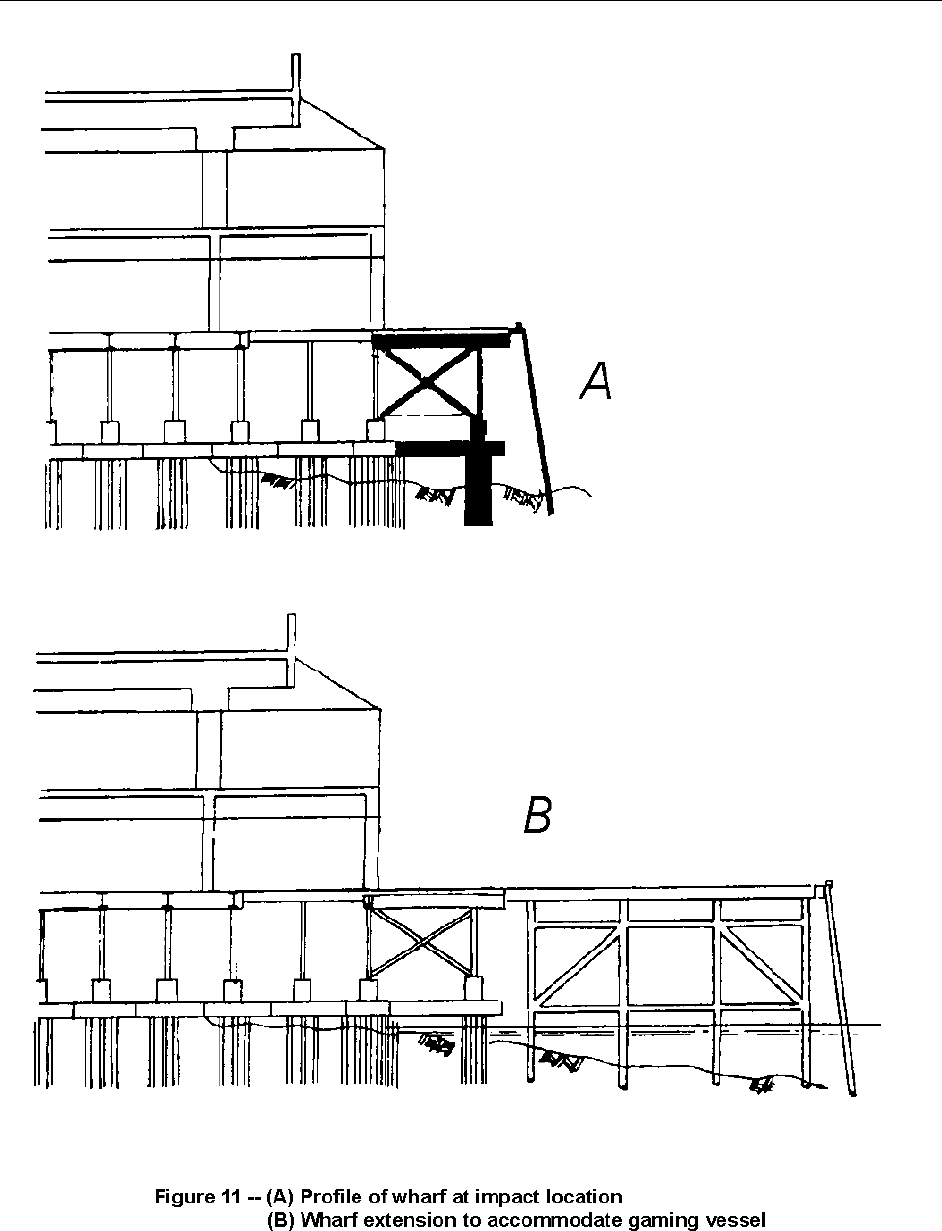

Figure 3 -- engine control room layout showing

reported positions of crewmembers when engine power

reduction occurred.

Bright Field

0DL Q#(QJLQH

*DXJHV

7HUDVDNL#0RQLWRUV

0DLQ#(QJLQH

&RQWUROV

(QJLQH HU·V

:RUNVSDFH

'HVN

6HFRQG#(QJLQHHU

&KLHI#(QJLQHH U

7KLUG#(QJLQHHU

(OHFWULFDO#6ZLWFKERDUGV#)#0RWRU#&R QWUR OOHUV

)25: $5'

(QJLQHHULQJ#FRQWURO/#PRQLWRU/#DQG#DODUP#FRQVROH

0DLQ

(QJLQH

5HPRWH

&RQWURO

&LUFXLWV

$2&

Figure 4 -- Engineering control, monitor, and alarm console

8

he made aware by the mate or the master, that

vessel power had been restored. The pilot said

that he was not aware of what, if any, actions

the master or the crew were taking to restore

power. The master’s orders to the second mate

and the second mate’s conversations with the

chief engineer were in Chinese.

The vessel continued to swing to port and

toward the left descending bank. The pilot told

the master to prepare to drop anchors and

ordered the main engine full astern. The vessel’s

bell logger tape, which continuously captures

data and prints it out in 30-second intervals,

recorded that the full-astern order was made

from the bridge at 1409.5 and answered by the

engine control room at 1410.0. The chief

engineer stated that he reversed the engine and

ran the shaft speed to 20 to 40 (fluctuating) rpm

astern.

The pilot stated that, shortly thereafter, he

ordered the anchors dropped. The master said

the pilot ordered only the port anchor dropped,

that he concurred with that order, and that

though he did not acknowledge the order to the

pilot, he attempted to carry it out. The master

said that he attempted to call the carpenter on

the forecastle using the handheld radio. The

carpenter, who was standing by the anchors,

said that he could not hear radio transmissions

from the master because the danger signal was

still being sounded on the ship’s whistle, which

was located about 20 feet above his station on

the bow. The master said he made repeated

unsuccessful attempts to contact the carpenter

but did not ask the pilot to suspend the sounding

of the danger signal. The pilot stated that he

stopped sounding the signal only long enough to

make short radio transmissions to the traffic

light operators to urge them to call the New

Orleans Riverwalk complex and “tell the people

to get away from the dock.”

The master stated that he rushed out to the

port bridge wing and waved his arms to attract

the carpenter’s attention. When he realized that

the carpenter did not see him, the master went

back inside the bridge. Once back inside,

intermittent communications were established

between the master and the carpenter. By the

time reliable communication was established,

the ship had moved farther toward the wharf,

and the master said he believed that dropping

the anchor at that time would cause the ship to

take a sharp turn to the left and perhaps strike

one of the vessels docked there. He said he

therefore told the carpenter not to drop the

anchor. The master said that after the ship had

moved a little farther, he again contacted the

carpenter and told him to drop the anchor to

keep the ship from striking the docked vessels.

The carpenter said he turned the brake wheel to

let go of the port anchor and then ran from the

bow to avoid being injured in the imminent

allision. Postaccident review of an amateur

videotape of the allision indicated that the

anchor did not drop prior to impact.

According to statements of the pilot and

crewmembers, the pilot did not ask either the

master or second mate if the vessel’s power had

been restored or if the anchors had been

dropped, and no one volunteered that

information. The pilot said he had not felt any

engine vibrations, though he expected to. He

said, “When that big engine turns, you feel it.”

The master said the vibrations caused by the

engine when it started in reverse while the ship

was still moving forward were obvious. No

further communications were reported between

the pilot and master or the pilot and the second

mate before the allision.

Meanwhile, the cruise ship

Enchanted Isle

was docked at the Erato Street wharf on the left

descending bank of the river. Passenger

embarkation had begun about 1230, and about

200 passengers were on board. Crewmembers

aboard the cruise ship did not (and were not

required to) monitor VHF channel 67 and

therefore did not hear any radio announcement

from the traffic light operator regarding the

Bright Field

. They did state that they heard the

vessel’s danger whistle. The third officer said he

was on the bridge as the

Bright Field

passed

under the Crescent City Connection Bridges and

that he knew the vessel was in trouble when he

heard its whistle blow for the fifth time. He

stated that he ran out onto the outside deck and

saw the

Bright Field

passing his ship on a direct

path to the Riverwalk area. The ship’s master,

who had also heard the

Bright Field’

s whistle,

reached the bridge as the

Bright Field

went past.

The officers activated the public address system

and placed the bridge on standby to close the

watertight doors. The third officer said that he

and the master called for the forward dock lines

9

to be tightened to protect against gangway

displacement as the

Bright Field

bow wave

struck the vessel. They also notified the

gangway watchman of a possible river surge and

sent two crewmen to watch over the gangway

and report any trouble back to the bridge.

According to the third officer, the

Bright Field

was clear of the

Enchanted Isle

throughout the

accident sequence.

Moored about 150 to 200 feet downriver

from the stern of the

Enchanted Isle

was the

cruise ship

Nieuw Amsterdam

. The ship had

begun embarking passengers about 1330, and an

estimated 200 to 300 passengers were on board

at the time of the accident. The crew did not

(and was not required to) monitor VHF channel

67. The second officer said he was standing

behind the port-side radar when his attention

was drawn to a ship on the river sounding an

emergency alarm. The second officer reported

that he could not immediately determine which

vessel was sounding the alarm, so he and the

chief officer went out to the port side bridge

wing (the vessel was docked with its starboard

side toward the wharf) and saw the

Bright Field

passing under the Crescent City Connection

Bridges. They said they stood and watched the

Bright Field

as it headed toward their ship and

the Poydras Street wharf area. They entered the

wheelhouse to warn the on-duty third officer.

The

Nieuw Amsterdam

’s on-duty third

officer said he also had heard the multiple

whistle signals and had watched the

Bright

Field

as it passed under the bridges with its bow

pointing toward his vessel. He said that the

Bright Field

appeared to be about 1/2 nautical

mile away and moving at 8 to 10 knots. Based

on his observations of the

Bright Field’

s

direction of travel and the whistle sounding, he

said, he assumed the vessel was experiencing

steering or engine failure. He immediately

warned the master, who was in his stateroom

directly behind the bridge.

The

Nieuw Amsterdam

’s master instructed

the on-duty officer to tell the security officer at

the gangway to stop the embarkation of

passengers. The on-duty officer was then to

place the bridge on standby, close the watertight

doors, and activate the public address system.

The master instructed the second and third

officers to go to the stern of the ship with radios

and to evacuate the Lido deck aft, then clear the

decks on the port side and monitor the situation.

The crew said that after 2 or 3 minutes it was

apparent that the

Bright Field

would not strike

the

Nieuw Amsterdam

. The master and the on-

duty officer followed the progress of the

Bright

Field

from the port wing bridge. They assessed

the situation and determined that the

Bright

Field

would miss the

Nieuw Amsterdam

by

approximately 50 meters (164 feet).

The first mate of the gaming vessel

Queen

of New Orleans

, which was docked at the

Poydras Street wharf with its bow less than

1,000 feet downriver from the stern of the

Nieuw Amsterdam

, had overheard the

Bright

Field

pilot’s call to the traffic light operator on

VHF channel 67 (although the vessel was not

required to monitor the frequency) and had

immediately begun emergency evacuation of the

637 passengers and crewmembers aboard the

vessel.

20

Meanwhile, the excursion vessel

C

reole Queen

, which had been docked at the

Canal Street wharf downriver from the

Queen of

New Orleans

, was in the process of pulling

away from the dock with 190 passengers and

crew on board. The master said he heard the

pilot of the

Bright Field

radio the Governor

Nicholls light operator and report, “I’ve lost

everything. The ship is heading toward the

passenger vessels.” The master said that he

returned the vessel to the dock and ordered an

emergency evacuation.

According to the results of Safety Board

surveys, patrons and employees of the

Riverwalk Marketplace along Poydras Street

wharf and the adjacent Julia Street and Canal

Street wharves were unaware of the meaning of

the warning whistles from the

Bright Field

.

Several harbor police officers did recognize the

warning whistles and tried to clear the area.

While they did so, some marketplace patrons

and staff members noticed the

Bright Field

heading toward them, and large numbers began

to flee. Many individuals sustained injuries

during the evacuation. The harbor police were

able to move most of the crowd away from the

expected impact area. Many of those in the area

20

For a detailed discussion of all the vessel

evacuations, see the “Survival Aspects” section of this

report.

10

said that they did not know what was happening,

and because they had had so little advance

notice of a potential hazard, they did not have

the opportunity to obtain information from mall

employees or security officers.

About 1411, the port bow of the

Bright

Field

struck the Poydras Street wharf at a

location between the docked

Nieuw Amsterdam

and

Queen of New Orleans

. (See figure 5.) The

vessel struck the wharf at what witnesses said

was a 40- to 45-degree angle, went into the

wharf up to the end of the forecastle deck (about

50 to 60 feet), and then made a sideways

movement. The bow portion of the vessel

scraped and collapsed portions of the buildings

on the Poydras Street wharf, including a portion

of the Riverwalk Marketplace shopping mall, a

condominium parking garage, and part of the

Hilton Riverside Hotel. The ship came to rest

against the wharf with its stern about 200 feet

from the stern of the

Nieuw Amsterdam

and its

bow about 70 feet from the bow of the

Queen of

New Orleans

. (See figure 6.) The pilot ordered

the engine stopped, after which several tugboats

arrived to hold the ship against the dock. About

3 minutes had elapsed from the time the pilot

made his first emergency call to the Coast Guard

light operator until the ship struck the wharf.

Injuries

The accident resulted in 4 serious and 58

minor injuries to persons in the Riverwalk area,

aboard the

Queen of New Orleans

, or aboard the

excursion vessel

Creole Queen

, which was

docked near the

Queen of New Orleans

. (See

table 1.)

Vessel Damage

After striking the wharf, the bow of the

Bright Field

grated along the concrete and steel

wharf structure for a distance of about 600 feet.

The allision damaged the port side of the bow.

The hull of the vessel sustained two horizontal

gashes about 100 feet long that penetrated the

port side of the ship and extended down the port

side from the fore peak (bow) ballast tank and

into the No. 1 cargo hold. Both the breached

fore peak tank and the No. 1 cargo hold flooded.

A diver found a 100-foot section of the forward

hull resting on the river bottom adjacent to the

Poydras Street wharf. Total damages to the

Bright Field

were estimated to be about $2

million. (See figure 7.) The vessels that had

been docked in the allision area did not sustain

significant damage.

Other Damage

The One River Place condominium

building, located on the Poydras Street wharf,

sustained damage to its valet parking garage.

Residents of the building were evacuated

because of a loss of power and water. The

Riverwalk Marketplace, a mall with 100 stores,

3 restaurants with outdoor seating, and a large

wharf walkway, sustained damage to more than

350 feet of its wharf frontage. About 10 percent

of the mall shops and restaurants were affected.

The New Orleans Hilton Riverside Hotel, part

of which was situated on the Poydras Street

Table 1 -- Injuries Sustained in Bright Field Allision

1

+0,74+'5 4KXGTYCNM"#TGC 3WGGP"QH"0GY"1TNGCPU %TGQNG"3WGGP 7PMPQYP 6QVCN

(#6#. 22222

5'4+175 34326

/+014 38 32 5 4; 7:

010' 52247

616#. 42 34 6 53 89

1

Table

based on the injury criteria (49 CFR 830.2) of the International Civil Aviation Organization, which the

Safety Board uses in accident reports for all transportation modes.

11

N

$/*,(56

3RLQW#

0LOH #<717

0LOH #<8

)HUU\

7HUPLQDO

0,66,66,33,

5LYHU#)ORZ

7R#*XOI#RI

0H[LFR

)HUU \#

7HUPLQDO

&UHROH

4XHHQ

:ROGHQEHUJ

3DUN

:RUOG#7UDGH

&HQWHU#EXLOGLQJ

1121#+LOWRQ

5

L

Y

H

U

Z

D

O

N

4XHHQ#RI#1HZ

2UOHDQV

1HZ#2UOHDQV

&RQYHQW LRQ#)

([KLELWLRQ

&HQWHU

&UHVFHQW#&LW\

&RQQHFWLRQ#%ULGJHV

0LOH

<81:

&

$

1

$

/#

6

7

1

-DFNVRQ#6TXDUH

)UHQFK#4XDUWHU

7

R

X

O

R

X

VH

#

6

W

:K

D

U

I

%LHQYLOOH#6W1

:KDUI

&DQDO#6W1

:KDUI

3R\GUDV#6W1

:KDU I

-XOLD#6W1

:KDUI

(UDWR#6W1

:KDUI

7XJ#/RFNPDVWHU

/RFDWLRQ

1LHXZ#$PVWHUGDP

(QFKDQWHG

,VOH

%

U

L

J

K

W

#

)

L

H

O

G

%

U

L

J

K

W

#

)

L

H

O

G

Fi

g

ure 5 -- Path of Bri

g

ht Field (not to scale)

$

T

XD

U

L

XP

13

Figure 7 -- Damaged Bright Field being towed away from Poydras Street wharf en route to repair

facility, January 6, 1997

14

wharf, sustained damage to 40 of its 1,600

rooms. Total damages to all facilities were

estimated to be about $18 million. (See figures 8

and 9.)

Crew Information

The Pilot

-- The

Bright Field

pilot, age 46,

had been a NOBRA pilot for about 17 years. He

began his maritime career in 1969 when he

started working on the Mississippi River during

college summer vacations. He served as a

deckhand aboard the

Delta Queen

, a

paddlewheel passenger vessel, and as a

deckhand and mate aboard other passenger

vessels, including the

Mississippi Queen

and the

Natchez.

He also worked for a barge line

operating on the Illinois River between St. Louis

and Chicago.

In 1975, the pilot graduated from a 2-year

program at the National River Academy in

Helena, Arkansas. The program consisted of

periods of 2 months of classroom instruction

followed by 2 months on a river vessel. He

obtained his first Coast Guard license, an inland

mate’s license, in 1975. He was commissioned

by the New Orleans Baton Rouge State Pilots

Commission as a pilot on January 16, 1980. At

the time of the accident, he was a licensed river

master and first class pilot. The most recent

renewal of his license had been on May 5, 1995.

The pilot said that he had piloted on most of

the vessel types transiting the Mississippi River.

He said he navigated primarily foreign flag

vessels anywhere from the New Orleans general

anchorage to Baton Rouge. The majority of

these were deep-draft vessels, although he said

he occasionally worked a seagoing tug and

barge. He said he averaged about 7 vessel

assignments per week, totaling between 200 and

300 ships each year. He stated that he had not

attended any ship simulator training, and he

believed that only one NOBRA pilot had

attended such training. He said he had not

received any bridge resource management

(BRM)

21

training and was, in fact, unfamiliar

with the term and the concept.

21

Bridge resource management entails effective use of

all available resources to achieve safe operations.

The pilot stated he had been involved in

three previous accidents. In 1983, the vessel he

was piloting struck a bridge when a

crewmember raised a boom too high. The

second event occurred when the vessel he was

piloting lost steering shortly after he came

aboard. The vessel moved hard to starboard and

hit a ship launch dock. The third event took

place in spring 1996, when the pilot was

working on board a vessel that lost rudder

control and struck the river bank.

For the 4 days prior to the accident, the pilot

said, he had kept essentially the same

sleep/wake schedule, arising shortly after

daylight, about 0700, and retiring between 2230

and 2300. He reported that he had slept well the

night before the accident, did not have any sleep

abnormalities, and did not suffer from any

illnesses. He said he was not sick and that he

had taken no medications on the day of the

accident.

The Master

-- The

Bright Field

master, age

35, had been in the maritime industry for 14

years. He began as an able seaman before

becoming an apprentice officer. He then

progressed from third, to second, to first, to

chief officer, and then to master. He had been a

master for a little more than 1 1/2 years and had

served on three different ships. He said he had

been master of the

Bright Field

for about 15

weeks at the time of the accident (since August

25, 1996). During his time with the

Bright Field

,

he had spent about 3 months at sea and about 1

month in port. He said he had been to New

Orleans twice before, in 1983 and 1989;

however, this was his first trip as master. He

said he had never, on any vessel, experienced a

reduction in engine rpm of the kind that

occurred just prior to this accident.

The master attended the Dalien Maritime

Academy in China for 4 years and graduated in

August 1982. His training involved more than

40 deck officer-related courses. It also included

computer-based simulator training in ship

handling and maneuvering. He said he had

received additional simulator training on two

occasions at the Qingdao Mariner’s Training

School. The first occasion involved radar

plotting and ship handling to qualify for his

radar observer’s endorsement. The second

involved the handling of large vessels and

15

Figures 8 and 9 -- Postaccident scenes

16

occurred after he had passed his master’s

examination.

The master held a People’s Republic of

China Marine Certificate of Competency, which

certified that he was qualified to be a master of

ships of 1,600 gross tons or more. The most

recent endorsement of that certificate had been

on April 20, 1995. He also held a Republic of

Liberia license certifying his competence as a

master and radar observer on oceangoing vessels

of any gross tonnage. The most recent

endorsement of that license had been on October

3, 1996. Both licenses are valid for 5 years.

The master indicated he had received

training that emphasized coordination among

the bridge team, including the pilot. He said his

training covered the duties and responsibilities

of each individual and stressed the need to be

able to communicate with one another and assist

one another in the performance of their duties.

He said the training also stressed the integration

of the various responsibilities.

The master noted that, since he had held the

position of master, he had overruled pilots on

four occasions. On this trip he said,

I…instructed the carpenter not to drop

the anchor, which in effect…overruled

the pilot, because the pilot [had]

instructed [me] to drop the anchor. [I]

instructed the carpenter not to drop the

anchor because [it] would [cause the

Bright Field

to] swerve towards the

passenger ship. That, in effect, is a way

of overruling the pilot.

The master said he did not confer with the

pilot about the change in the timing of the drop-

anchor order because there was “no time.”

The master reported that he began to learn

English when he entered the maritime academy.

He characterized his English language skills as

“not bad among Chinese,” though he noted that

his ability to read the language was better than

his ability to speak it. He said he did not have

any difficulty understanding the pilot on this

trip.

The master stated that he was required to be

available 24 hours a day but that his normal

schedule involved going to bed at midnight and

arising at 0700 each day. He said he had kept

this schedule on the night before the allision,

arising about 0715 after a complete night’s

sleep. He reported that he was not suffering

from any long-term illnesses and that he was not

sick and took no medications on the day of the

accident.

The Chief Engineer

-- The

Bright Field’

s

chief engineer, age 34, began his maritime

career in 1979. He studied marine engineering at

the Jimei Maritime School, graduating in 1982.

He said he had been sailing aboard ships as an

engineer since his graduation. He said he had

been a chief engineer for 4 years, had been with

his current employer for 1 month, and had been

chief engineer aboard the

Bright Field

for 3

weeks prior to the allision. He came aboard the

Bright Field

for the first time on November 21,

1996, to replace the vessel’s previous chief

engineer (see below), who had been relieved of

duty upon the vessel’s arrival in New Orleans.

The chief engineer stated that he had served

on ships with both more and less automated

engineering equipment than the

Bright Field

and

that he was comfortable with the

Bright Field

’s

automation. He also said he had received

training on automated ship systems at the Dalien

Maritime Academy in 1993 and that the last

ship he served on before the

Bright Field

was

equipped with a similar system. While aboard

the

Bright Field

, he had been underway on short

transits on four occasions for a total of 11 hours.

During those occasions he said there were no

engine casualties or automation problems,

although various main engine repairs had been

made while the ship was at anchor during the 3

weeks he had been aboard.

The chief engineer held a People’s Republic

of China Marine Certificate of Competency,

which certified that he was qualified as a chief

engineer of ships of 3,000 kw (kilowatt, or

4,023 hp) propulsion power or more. The most

recent endorsement of that certificate had been

on October 27, 1993. He also held a Republic of

Liberia license certifying his competence as a

chief engineer on motor vessels of any

propulsion power. The most recent endorsement

17

of that license had been on May 23, 1995. Both

licenses are valid for 5 years.

The chief engineer reported that his normal

work day began at 0800 and ended at 1700. His

normal sleep schedule was to go to bed at 2300

and arise at 0700. In the 2 days prior to the

allision, the

Bright Field

was at anchor, and the

engineer was involved in some repairs. On

December 12, the turbocharger was repaired.

Work began in the evening and was completed

at 0220 the following morning, December 13.

The chief engineer said he then went to bed and

got up shortly after 1000. That night he went to

bed before 2300 and was awakened just after

0600 on December 14 by the air cooler

technician, who needed his signature. He said he

remained awake, but he did not actually start

working for the day until about 0920.

The chief engineer reported that he was not

suffering from any long-term illnesses and that

he was not sick and had taken no medications on

the day of the accident.

The Previous Chief Engineer

-- The

vessel’s previous chief engineer had joined the

Bright Field

in April 1996. He left the vessel in

New Orleans on November 21, 1996, after being

fired for what a company representative said

was his failure to comply with company orders

about the maintenance and operation of the

Bright Field’

s engineering plant.

Vessel Information

Four vessels were docked near the point at

which the

Bright Field

struck the wharf. The

Enchanted Isle

was docked at the Erato Street

wharf, and the

Nieuw Amsterdam

was docked at

the Julia Street wharf. The gaming vessel

Queen

of New Orleans

was docked at the Poydras

Street wharf in front of the Hilton Riverside

Hotel. The excursion vessel

Creole Queen

was

docked at the Canal Street wharf.

Bright Field

--The

Bright Field

, a bulk

cargo carrier with seven cargo holds, was built

in 1988 by Sasebo Heavy Industries Co. Ltd., of

Japan. At the time of the accident, the ship was

owned by Clearsky Shipping Company, a

Liberian corporation, and operated by Cosco

H.K. Shipping Company, of Hong Kong. The

Liberian-registered vessel was 735 feet long,

weighed 68,200 deadweight tons, and had a

maximum breadth of 106 feet.

The

Bright Field

was classed

22

by Det

Norske Veritas (DNV) for periodically

unattended machinery space. When the

Bright

Field

was delivered, the original owners elected

to have the unattended machinery space en-

dorsement include specifications for preventive

maintenance and routine testing of automatic

propulsion system components, and the

procedures were verified periodically by DNV.

The current owner of the vessel elected not to

continue the preventive maintenance

endorsement of the original class certification.

The vessel was equipped with an IHI Sulzer

RTA62 slow-speed, five-cylinder, two-cycle,

turbocharged, reversible diesel engine

manufactured by Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy

Industries (IHI) of Aioi, Japan. The 9,655-brake

hp (7,200 kw) engine was directly coupled to a

24-foot-diameter, four-blade, bronze propeller

capable of driving the vessel to a speed of 15.5

knots at sea speed.

23

A change from ahead to

astern required that the engine be stopped and

restarted with shaft rotation in the opposite

direction. A high-pressure compressed-air

system was used to start the engine in either

direction and also to stop its rotation during a

change from ahead to astern or vice versa.

The

Bright Field’

s engine was fitted with

protective devices (alarms and shut downs),

sensors (pressure, temperature, etc.), and

automatic control equipment. In support of

unattended machinery operation, the vessel was

equipped with engine controls located on the

bridge.

The

Bright Field

was configured as a

conventional bulk carrier with an aft

engineering plant and accommodation house.

The navigation bridge was fitted with a chart

table, navigation equipment, and an automatic

22

6JG" CRRNKECDNG" &08" TWNGU" KPEQTRQTCVGF" VJG

+PVGTPCVKQPCN" #UUQEKCVKQP" QH" %NCUUKHKECVKQP" 5QEKGV[IU

*+#%5+"WPKHKGF"TWNGU"CPF"VJG"

International Convention for

the Safety of Life at Sea

(SOLAS),

%JCRVGT"33/3."2CTV"'0

23

Because of the relatively rapid river current on the

day of the accident, the

Bright Field

was traveling at an

effective speed that exceeded its rated sea speed.

18

radar plotting aid (ARPA)

24

in its after part.

Facing toward the bow, forward of the chart

table to starboard of centerline, was the engine

control console with engine order telegraph. To

the left of the console on the centerline was the

helm control console, comprising the helm, gyro

compass, and magnetic periscope compass.

Forward of the console and suspended from the

overhead was a rudder angle indicator and

engine order indicator. Below the forward

bridge windows was a gyro repeater, radar, VHF

marine radio, and manual buttons for the ship’s

whistles.

Although not required by U.S. or Interna-

tional Maritime Organization regulations, the

vessel was equipped with a course recorder. In-

vestigators determined that, at the time of this

accident, the unit was inoperative because of

leaking graph recording pens. Examination of

the course recorder paper determined that the

unit had probably been out of service for some

time. When in working order, the unit records

the ship’s gyro heading over time.

The vessel was equipped with an engine

telegraph logger that automatically recorded

engine telegraph orders (date and time) from the

bridge and acknowledgments of the orders from

the engine control room. The logger also noted

whether the engine was being operated from the