1

Notice and Explanation of the Basis for the

Financial Stability Oversight Council’s Rescission of Its Determination

Regarding American International Group, Inc. (AIG)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Overview ................................................................................................................................ 2

2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 2

2.1 Annual Reevaluation Process ....................................................................................... 2

2.2 Summary of Council Basis ........................................................................................... 3

2.3 Summary of Annual Reevaluation Conclusion............................................................. 5

2.4 Summary of AIG’s Submission to the Council ............................................................ 7

3. Legal Framework for Annual Reevaluations of Determinations ........................................... 9

3.1 Scope of Reevaluation .................................................................................................. 9

3.2 AIG’s Status as a Nonbank Financial Company ......................................................... 10

4. Overview of AIG ................................................................................................................. 10

5. Transmission Channel Analysis ........................................................................................... 15

5.1 Overview ..................................................................................................................... 15

5.2 Exposure Transmission Channel................................................................................. 15

5.3 Asset Liquidation Transmission Channel ................................................................... 31

5.4 Critical Function or Service Transmission Channel ................................................... 49

6. Complexity and Resolvability.............................................................................................. 54

7. Existing Regulatory Scrutiny ............................................................................................... 62

7.1 Regulatory Developments ........................................................................................... 62

7.2 Regulator Consultations .............................................................................................. 65

8. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 65

Appendix A: Condensed Consolidated Balance Sheet ($ Billions) .............................................. 66

Appendix B: Fire Sale Model Detail ............................................................................................ 67

Note: Redactions of confidential information submitted to the Council

by AIG or its regulators are indicated by “[•]”

2

1. OVERVIEW

Section 113(d) of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-

Frank Act) requires the Financial Stability Oversight Council (Council) not less frequently than

annually to reevaluate its determination that material financial distress at AIG could pose a threat

to U.S. financial stability and that AIG shall be subject to supervision by the Board of Governors

of the Federal Reserve System (Board of Governors) and enhanced prudential standards. In

conducting its analysis of AIG, the Council relied on the information and materials cited herein,

including written materials submitted by AIG, and consultations with the New York Department

of Financial Services, the Texas Department of Insurance, the Pennsylvania Insurance

Department, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Board of Governors, and the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). For the reasons described herein, the Council has

rescinded its final determination that material financial distress at AIG could pose a threat to

U.S. financial stability and that AIG shall be supervised by the Board of Governors and be

subject to enhanced prudential standards.

2. INTRODUCTION

2.1 Annual Reevaluation Process

Pursuant to section 113 of the Dodd-Frank Act, on July 8, 2013, the Council made a final

determination that material financial distress at AIG could pose a threat to U.S. financial

stability and that AIG shall be subject to supervision by the Board of Governors and enhanced

prudential standards. The Council also determined that AIG was predominantly engaged in

financial activities, and therefore eligible for a final Council determination.

1

The Council is

required to review a final determination not less frequently than annually and rescind any

determination if the Council, by a vote of not fewer than two-thirds of the voting members then

serving, including an affirmative vote by the Chairperson of the Council, determines that the

nonbank financial company no longer meets the statutory standards for a determination.

2

This reevaluation was conducted in accordance with the Dodd-Frank Act, the Council’s rule

and interpretive guidance regarding nonbank financial company determinations (Rule and

1

The Council is authorized to determine that a “nonbank financial company” will be subject to supervision by the

Board of Governors and prudential standards if either of the two statutory standards established in section 113 of the

Dodd-Frank Act is satisfied. A “nonbank financial company” includes a company that is incorporated or organized

under the laws of the United States or any state and is predominantly engaged in financial activities. 12 U.S.C.

§ 5311(a)(4)(B). A company is “predominantly engaged in financial activities” if at least 85 percent of the

company’s and its subsidiaries’ annual gross revenues are derived from, or at least 85 percent of the company’s and

its subsidiaries’ consolidated assets are related to, “activities that are financial in nature” as defined in section 4(k) of

the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, as amended. See Dodd-Frank Act section 102(a)(6),

12 U.S.C. § 5311(a)(6); see also 12 C.F.R. part 242.

2

Dodd-Frank Act section 113(d), 12 U.S.C. § 5323(d).

3

Interpretive Guidance),

3

and the Council’s Supplemental Procedures Relating to Nonbank

Financial Company Determinations (Supplemental Procedures).

4

On March 18, 2016, the Council sent a letter to AIG informing the company that the Council

was conducting its annual reevaluation of AIG. AIG was notified that it could request to meet

with staff of the Nonbank Financial Company Designations Committee (Nonbank Designations

Committee) to discuss the scope and process for the review and to present information

regarding any change that may be relevant to the threat the company could pose to financial

stability. AIG was asked to submit any written materials to the Council to contest the

determination by May 2, 2016. At AIG’s request this deadline was extended to August 3, 2016

and then again to November 1; in requesting the second extension to November 1, AIG

expressly waived any right it might have had for the reevaluation to be completed in 2016. On

November 1, 2016, AIG notified the Council that it was not contesting the Council’s

determination. On April 17, 2017, the Office of Financial Research, on behalf of the Council,

sent a letter to AIG requesting certain additional nonpublic information from the company that

would assist in the Council’s reevaluation analysis. Between May 25 and July 24, 2017, AIG

submitted its responses to the Council’s request. On July 17, 2017, AIG submitted additional

materials in which the company requested that the Council rescind its determination.

2.2 Summary of Council Basis

In making a final determination with respect to AIG in 2013, the Council evaluated the extent to

which material financial distress at AIG could be transmitted to other financial firms and markets

and thereby pose a threat to U.S. financial stability through the following three transmission

channels: (1) the exposures of creditors, counterparties, investors, and other market participants

to AIG; (2) the liquidation of assets by AIG, which could trigger a fall in asset prices and thereby

could significantly disrupt trading or funding in key markets or cause significant losses or

funding problems for other firms with similar holdings; and (3) the inability or unwillingness of

AIG to provide a critical function or service relied upon by market participants and for which

there are no ready substitutes. The Council considered each of the statutory factors set forth in

section 113 of the Dodd-Frank Act in conducting the transmission channel analysis.

5

The

Explanation of the Basis of the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s Proposed Determination

that Material Financial Distress at AIG Could Pose a Threat to U.S. Financial Stability and that

AIG Should be Supervised by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and

Subject to Prudential Standards, approved by the Council on June 3, 2013 (Council Basis),

contains a detailed explanation of the Council’s basis for its determination regarding AIG.

6

3

Council, Authority to Require Supervision and Regulation of Certain Nonbank Financial Companies, 12 C.F.R.

part 1310.

4

Council, Supplemental Procedures (February 4, 2015), available at

https://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/fsoc/designations/Documents/Supplemental%20Procedures%20Related%20to

%20Nonbank%20Financial%20Company%20Determinations%20-%20February%202015.pdf.

5

See 12 C.F.R. part 1310.

6

The Council provided AIG with a detailed explanation of the basis of the Council’s proposed determination

regarding the company in June 2013. Because AIG did not contest the Council’s proposed determination, at the

time of the Council’s final determination the Council approved and sent to AIG only the public explanation of the

4

The Council determined that the threat to U.S. financial stability posed by AIG’s material

financial distress arose primarily from the exposure and asset liquidation transmission channels,

although the Council also concluded that the critical function channel could exacerbate the extent

to which the company’s material financial distress could be transmitted to the financial system

and the broader economy. The Council also concluded that AIG’s complexity and the potential

difficulty to resolve AIG could exacerbate the risks posed by AIG’s material financial distress

across all three transmission channels.

In evaluating the potential threat that material financial distress at AIG could pose to U.S.

financial stability through the exposure transmission channel, the Council analyzed the exposures

of AIG’s creditors, counterparties, investors, and other market participants to AIG. The Council

determined that significant losses to large financial intermediaries exposed to AIG could impair

financial intermediation or financial market functioning sufficiently and severely enough to

significantly impair the broader economy and thereby could pose a threat to U.S. financial

stability.

In considering the potential threat that material financial distress at AIG could pose to U.S.

financial stability through the asset liquidation transmission channel, the Council analyzed the

extent to which AIG held financial assets that, if liquidated quickly, could significantly disrupt

financial markets or the broader economy. The Council concluded that a rapid liquidation of

AIG’s life insurance and annuity liabilities could strain AIG’s liquidity resources and compel the

company to sell assets in order to satisfy its obligations. The Council found that because AIG

had a limited base of highly liquid assets, it could be forced to liquidate a substantial portion of

its large portfolio of relatively illiquid corporate and foreign bonds, as well as asset-backed

securities, and that this asset liquidation could have disruptive effects on the broader financial

markets and impair financial market functioning.

7

The Council also found that if AIG were to

suffer material financial distress in the context of corresponding doubt about the ability of the

company to satisfy its obligations, approximately [•] in annuity contracts and [•] in life insurance

cash values could be easily withdrawn through surrenders or policy loan provisions. The

Council determined that if the company’s financial distress were sufficiently severe, products

that are susceptible to early withdrawals may be withdrawn regardless of the size of associated

surrender charges or tax penalties.

8

The Council also concluded that widespread withdrawals by AIG policyholders and the

associated deterioration of AIG’s financial condition could cause financial contagion, as the

negative sentiment and uncertainty associated with material financial distress at AIG spread to

other insurers. In particular, the Council stated that if AIG’s distress causes concern among

policyholders at other insurers, those insurers could also experience unanticipated increases in

basis of the Council’s final determination. As a result, the analysis herein generally refers to the Council’s

nonpublic explanation of the basis for the proposed determination regarding AIG, which was part of the

administrative record for the Council’s final determination regarding the company.

7

Council Basis, p. 4.

8

Council Basis, p. 4.

5

surrender activity that strains liquidity resources, potentially impairing the financial condition of

multiple insurers across the industry.

9

The written explanation of the basis for the Council’s proposed determination regarding AIG

contains the Council’s full analysis.

2.3 Summary of Annual Reevaluation Conclusion

The Council has identified changes since the Council’s final determination regarding AIG that

materially affect the Council’s conclusions with respect to the extent to which AIG’s material

financial distress could pose a threat to U.S. financial stability. Some of these changes are the

direct result of steps AIG has taken that have reduced the potential effects of the company’s

distress on other firms and markets. For example, AIG has reduced the amounts of its total debt

outstanding, short-term debt, derivatives, securities lending, repurchase agreements, and total

assets. Further, additional analyses conducted for purposes of this reevaluation, including

additional consideration of the effects of incentives and disincentives for policyholders to

surrender their life insurance policies and annuities (including analysis of historical evidence of

retail and institutional investor behavior), indicates that there is not a significant risk that a forced

asset liquidation by AIG would disrupt market functioning and thereby pose a threat to U.S.

financial stability.

As described in sections 5.2 and 5.4, capital markets exposures to AIG have decreased, and the

company has sold certain businesses in which it held dominant market shares, rendering the

company less interconnected with other financial institutions and smaller in scope and size. By

contrast, AIG has outstanding [•] of life insurance and annuity products that allow policyholders

to withdraw cash from the company upon demand, producing liquidity risk at the company and

creating the potential for AIG to be forced rapidly to liquidate assets in the event of its material

financial distress. While this liquidity risk is material, the Council’s analysis, set forth in section

5.3, indicates that the level of forced asset sales by AIG in the event of its material financial

distress may be lower than previously contemplated, which decreases the risk that these asset

sales could disrupt key markets or cause funding problems at other firms.

AIG is notably different from the company as it existed leading up to the financial crisis. Many

of the changes at AIG since 2007 occurred before the Council’s determination regarding the

company; however, in addition to the changes noted above that have occurred at AIG since the

Council’s determination, the company is following a corporate strategy not to engage in the

types of activities, including extensive capital markets activities, that were the primary source of

its risks before the financial crisis.

Following are the Council’s key conclusions regarding the potential for material financial

distress at AIG to pose a threat to U.S. financial stability through the exposure, asset liquidation,

and critical function or service transmission channels.

9

Council Basis, p. 4.

6

With respect to the exposure transmission channel:

• Direct and indirect capital markets exposures to AIG have decreased substantially since

2012 as AIG has exited certain business lines and transaction types. In particular, AIG

has reduced the amounts of its total debt outstanding, short-term debt, derivatives,

securities lending, repurchase agreements, and total assets, in some cases significantly.

• Exposures of institutional policyholders arising from AIG’s general account

10

insurance

products are [•]. AIG’s stable value wrap products increase the potential risks that AIG’s

material financial distress could pose to certain counterparties but do not appear to

contribute significantly to the threat that the company’s distress could pose to U.S.

financial stability because of the nature of the product and the diffuse market participants

who would ultimately bear these losses.

• Exposures of retail policyholders arising from AIG’s general account insurance products

are roughly similar to 2012 but do not contribute significantly to the risk that material

financial distress at AIG could pose to U.S. financial stability through the exposure

transmission channel. Additional analysis, described below, has been conducted for

purposes of this reevaluation regarding the potential effects of these liabilities on state

guaranty associations, including the effects of factors that would reduce the guaranty

associations’ obligations in the event of the insolvency of AIG’s insurance subsidiaries.

With respect to the asset liquidation transmission channel:

• AIG has outstanding [•] of life insurance and annuity products that allow policyholders to

withdraw cash from the company upon demand. AIG’s liquidity risk arises primarily

from the potential for holders of annuities issued by AIG to withdraw their policies. The

amount of general account liabilities associated with these annuities is [•] than in 2012.

AIG has [•] of annuities that can be surrendered for [•] in cash upon demand by

policyholders, compared to [•] in 2012.

• Counterparty terminations of their capital markets transactions with AIG—including

repurchase agreements, securities lending, and derivatives arrangements—would affect

the volume of AIG’s forced asset sales; however, AIG’s total liabilities arising from these

activities are small compared to the liabilities arising from its withdrawable life insurance

and annuity products.

10

A life insurance company’s invested assets are held in two types of accounts: the general account and one or more

separate accounts. An insurer’s general account assets are obligated to pay claims arising from its insurance and

annuity policies, debt, derivatives, and other liabilities. Separate accounts consist of funds held by a life insurance

company that are maintained separately from the insurer’s general assets. Assets in the general account support

contractual obligations providing guaranteed benefits and are subject to claims by the insurer’s creditors in the event

the insurer becomes insolvent. By contrast, for separate accounts, the investment risk is passed through to the

contract holder; the income, gains, or losses (realized or unrealized) from assets allocated to the separate account are

credited to or charged against the separate account. Therefore, non-guaranteed separate account liabilities are not

generally exposed to the insurer’s credit risk because they are insulated from claims of creditors of the insurance

company.

7

• With respect to AIG’s assets that could be liquidated in the event of increased liquidity

needs at AIG, the company’s investment portfolio is [•]. AIG currently holds [•] of

highly liquid assets and an additional [•] of investment-grade bonds, compared to [•] in

2012.

• A fire sale impact analysis suggests that relative to other large financial institutions, the

market impact of a downward shock to the net worth of AIG has decreased since 2012,

largely due to AIG’s decrease in size. As of December 31, 2016, AIG ranked 11th for an

equity shock, ranking it near PNC and Capital One, and 19th for an asset shock, ranking

it near HSBC and Credit Suisse.

• Additional consideration of the effects of incentives and disincentives for retail

policyholders to surrender policies, including analysis of historical evidence of retail and

institutional investor behavior, indicate that there is not a significant risk that a forced

asset liquidation by AIG would disrupt trading in key markets or cause significant losses

or funding problems for other firms with similar holdings.

With respect to the critical function or service transmission channel:

• AIG is a market leader in commercial insurance, including in the excess and surplus

market. However, its market share has declined since the Council’s determination

regarding AIG. Exceptions to this decline include the markets for directors and officers

(D&O) and errors and omissions (E&O) insurance, but companies that lose coverage

would still continue to operate while they worked to obtain a new insurance provider.

• AIG has exited two important financial markets by selling International Lease Finance

Corporation (a leading provider of commercial aircraft financing) and United Guaranty

Corporation (a leading provider of private mortgage insurance). The divestiture of

United Guaranty Corporation in particular reduced the risks AIG’s material financial

distress could pose through the critical function or service transmission channel.

AIG has reduced its multi-jurisdictional operations, simplified its legal structure, and reduced its

size and global footprint, but AIG continues to be a complex, highly interconnected organization,

and there are significant obstacles to its orderly resolution. However, in light of the conclusions

regarding the transmission channel analysis, the difficulty to resolve AIG and the potential for

the company’s disorderly resolution do not lead to a conclusion that AIG’s material financial

distress could pose a threat to U.S. financial stability.

For the reasons described herein, the Council has rescinded its final determination that material

financial distress at AIG could pose a threat to U.S. financial stability and that AIG shall be

supervised by the Board of Governors and be subject to enhanced prudential standards.

2.4 Summary of AIG’s Submission to the Council

On November 1, 2016, AIG submitted a response to the Council’s notification regarding the

annual reevaluation of the company. This submission (AIG Submission) indicated that AIG

was not formally requesting the Council to rescind the designation, but it included information

that AIG stated supports the position that the company should not be designated. On July 17,

8

2017, AIG submitted additional materials in which the company requested that the Council

rescind its determination and provided additional detail on changes at the company since 2007,

divestitures, comparisons to peer financial institutions, and an overview of AIG’s regulatory

oversight other than Federal Reserve supervision. The AIG Submission focused on a

description of changes to its business since the 2008 financial crisis and since the time of the

Council’s final determination. In particular, the AIG Submission stated that since the financial

crisis the company has:

• de-risked its business activities,

• de-leveraged its balance sheet,

• reduced its size and footprint,

• sold operations and businesses,

• simplified its operations and structure, and

• reduced its complexity and interconnectedness with other large financial institutions.

AIG stated that the extent to which material financial distress at AIG could be transmitted to the

broader economy through the exposure, asset liquidation, and critical function or service

transmission channels has been reduced. For example, the AIG Submission indicated that the

company’s focus on traditional insurance activities and its wind-down of non-core businesses—

such as the aircraft leasing and mortgage guaranty businesses (International Lease Finance

Corporation (ILFC) and United Guaranty Corporation, respectively)—have reduced its risk. The

AIG Submission also stated that at its current size, the company’s asset size and composition is

more in line with insurance companies that the Council did not advance for designation than it is

with insurance companies the Council has designated. In addition, the AIG Submission included

summary statistics showing a significant reduction in exposures of creditors, counterparties,

investors, and other market participants to AIG, a decrease in AIG’s use of leverage, and an

improvement in the company’s liability composition.

The AIG Submission noted developments in the extent of regulatory scrutiny of the company,

highlighting the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Solvency

Modernization Initiative, the evolution of supervisory colleges, and a number of other

developments, including implementation of the Own Risk and Solvency Assessment tool. The

AIG Submission also stated that the district court’s opinion in MetLife, Inc. v. Financial Stability

Oversight Council

11

“identified several flaws in the Council’s designation process which are

equally applicable to its designation of AIG.”

12

11

177 F.Supp.3d 219 (D.D.C. Mar. 30, 2016).

12

The district court’s decision in MetLife v. FSOC applies only to MetLife, and the government’s appeal of the

decision is currently pending before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. The AIG

Submission noted that AIG would “look to the Court of Appeals’ decision to inform the propriety of the Council’s

initial and continued designation of AIG.”

9

In its submission, AIG presented financial information as of June 30, 2016. Except as otherwise

noted, current financial information referred to herein is presented as of year-end 2016 and on

the basis of GAAP.

3. LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR ANNUAL REEVALUATIONS OF

DETERMINATIONS

3.1 Scope of Reevaluation

Section 113(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act provides that the Council shall, not less frequently than

annually, reevaluate each final determination regarding a nonbank financial company and rescind

that determination if the Council determines that the company no longer meets the statutory

standards for a determination.

13

The Council made its final determination with respect to AIG

under the first standard for a determination under section 113(a) of the Dodd-Frank Act—that

material financial distress at AIG could pose a threat to U.S. financial stability.

14

Pursuant to the

second standard under section 113(a), the Council may determine that the nature, scope, size,

scale, concentration, interconnectedness, or mix of the activities of a nonbank financial company

could pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States. The Council may subject a

nonbank financial company to Board of Governors supervision and prudential standards if either

the first or second determination standard is met.

15

Consistent with the statutory text, the Council described its process for annual reevaluations of

determinations when it adopted the Rule and Interpretive Guidance implementing its authority

under section 113. The preamble to the Rule and Interpretive Guidance states that the Council

expects that its reevaluations “will focus on any material changes with respect to the nonbank

financial company or the markets in which it operates since the Council’s previous review.”

16

In

addition, the Interpretive Guidance states that for purposes of considering whether material

financial distress at a nonbank financial company could pose a threat to U.S. financial stability,

the Council intends to assess the impact of the company’s material financial distress “in the

context of a period of overall stress in the financial services industry and in a weak

macroeconomic environment.” This analysis summarizes certain key findings from the Council

Basis, and focuses both on material changes since the Council’s prior annual reevaluation and on

the cumulative effect of any changes since the Council’s final determination regarding AIG.

Certain developments in AIG’s business are described herein to provide an understanding of the

current state of the company and to respond to the items raised in the AIG Submission. In this

annual reevaluation, the Council has relied on the information and analysis set forth or cited

herein. In order to provide context for some of the changes that have occurred at AIG, this

analysis also includes select financial information from periods before the Council’s designation

of AIG.

13

Dodd-Frank Act section 113(d), 12 U.S.C. § 5323(d); see also 12 C.F.R. § 1310.23.

14

Council Basis, p. 11.

15

Dodd-Frank Act section 113(a), 12 U.S.C. § 5323(a).

16

12 C.F.R. part 1310.

10

3.2 AIG’s Status as a Nonbank Financial Company

The Council’s determination that AIG was a “U.S. nonbank financial company” was made on the

basis of the company’s assets and revenues, as explained in the Council Basis.

17

Although only

one of the two tests for being “predominantly engaged in financial activities” is required to be

met for a U.S. company to be a “U.S. nonbank financial company,” the Council determined that

both tests had been met.

18

The Council specifically found that: (1) more than 85 percent of the

revenues of AIG and its subsidiaries are derived from activities that are financial in nature, and

(2) more than 85 percent of the assets of AIG and its subsidiaries are related to activities that are

financial in nature.

19

In light of the developments at AIG since the Council’s final determination, no changes have

been identified that would affect the Council’s determination that AIG is predominantly engaged

in financial activities under both the revenue test and asset test cited above, based independently

on (1) more than 85 percent of the revenues of AIG and its subsidiaries being derived from

activities that are financial in nature under section 4(k)(4) of the Bank Holding Company Act,

including subparagraphs (B) and (I), and (2) more than 85 percent of the assets of AIG and its

subsidiaries being related to

20

activities that are financial in nature under section 4(k)(4) of the

Bank Holding Company Act, including subparagraphs (B) and (I).

21

This conclusion is based on

an evaluation of AIG’s balance sheet and income statement, which reveal that nearly all of the

company’s U.S. and foreign revenues are derived from its insurance activities and that nearly all

of its assets are related to its insurance activities.

4. OVERVIEW OF AIG

AIG ranks among the United States’ largest insurance organizations by assets, and is among the

world’s largest providers of commercial, institutional, and individual insurance products. AIG

operates in more than 80 countries with 56,400 employees and 90 million clients around the

world.

22

Beginning in the 1980s and continuing up to the financial crisis, AIG grew and increased profits

by diversifying into noninsurance businesses. Many of the businesses into which AIG expanded

created exposures to the U.S. housing markets, either directly or indirectly, which caused

significant financial distress for AIG when the housing bubble burst. The largest problems that

AIG faced during the crisis stemmed from credit default swaps (CDS) written by AIG Financial

17

Council Basis, p. 17.

18

Council Basis, p. 17.

19

Council Basis, p. 17.

20

The “related to” assets-based test, set forth in section 102(a)(6)(B) of the Dodd-Frank Act, 12 U.S.C.

§ 5311(a)(6)(B), is broader in scope than the “derived from” revenues-based test, set forth in section 102(a)(6)(A) of

the Dodd-Frank Act, 12 U.S.C. § 5311(a)(6)(A).

21

12 U.S.C. § 1843(k).

22

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, pp. 3, 8; AIG Group Benefits,

Overview Brochure (2016), available at

https://www.aig.com/content/dam/aig/america-

canada/us/documents/business/group-benefits/aigb100656-brochure.pdf.

11

Products (AIGFP) and numerous securities lending and repurchase agreement activities. The

aftermath of downgrades of the securities underlying structured deals and of AIG itself led to

collateral calls in all three of these markets. Attempts to craft a private-sector rescue for AIG

were hindered by the extreme complexity of the internationally active organization. Moreover,

AIG’s intercompany dealings were in many cases very complicated, adding to the high degree of

interconnectedness among AIG’s subsidiaries and between subsidiaries and the parent company.

Initiatives conducted by the Board of Governors, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and

the Treasury Department, which began in September 2008, ultimately stabilized AIG. After

these government interventions, AIG began to substantially reduce its size and complexity by

selling off numerous subsidiaries and exiting nontraditional businesses (such as AIGFP). The

AIG Submission states that since the Council’s final determination in 2013, AIG has continued

to reduce its size and risk by selling non-core operations and businesses, simplifying its

operations, and focusing on its more traditional insurance businesses (i.e., its property and

casualty and life and retirement businesses).

23

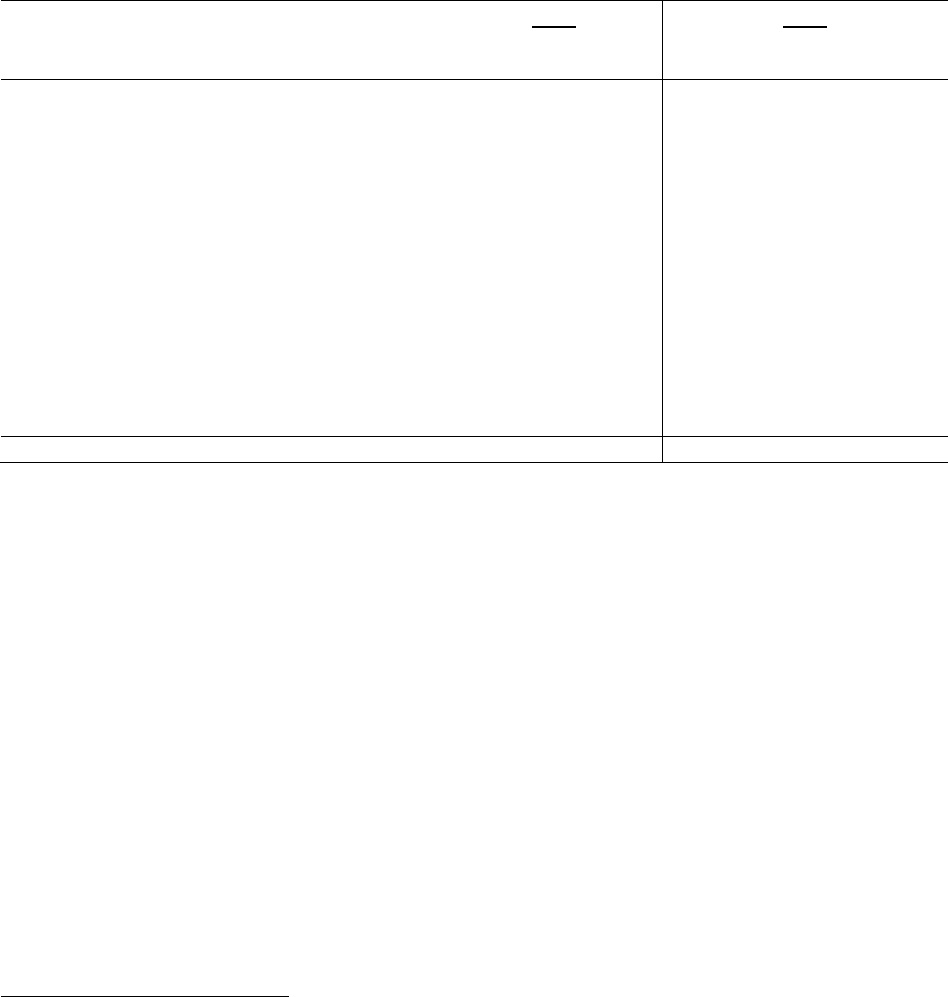

As of year-end 2016, AIG had total assets of $498 billion, $83 billion in separate account assets,

$31 billion of long-term debt, and a leverage ratio of 5.4x. As shown in Table 1, AIG’s total

debt decreased by 58 percent since 2012, when including the debt of subsidiary ILFC in 2012

($24.3 billion). Because of this reduction in debt, AIG’s leverage as measured by debt to equity

has decreased significantly since 2012, although the leverage ratio (as measured by total assets to

equity) has not followed this pattern because of share repurchases executed by the company in

the second half of 2016.

Table 1: Select Financial Information ($ Billions)

2007 2012 2016

Total Assets

1,048.4

548.6

498.3

Total Debt 176.0 72.8 30.9

Total Revenue 110.1 65.7 52.4

Debt-to-Equity Ratio 1.8x 0.7x 0.4x

Leverage Ratio 9.3x 5.0x 5.4x

Short-Term Debt Ratio

15.2%

2.9%

1.5%

Source: AIG Annual Reports on Form 10-K for the years ended December 31, 2008, December 31, 2012, and

December 31, 2016. Total debt includes $24.3 billion of ILFC debt in 2012 and excludes repurchase agreements

and securities lending and Federal Home Loan Bank borrowing. The leverage ratio is calculated as total assets

(excluding separate account assets) over total equity. The short-term debt ratio is calculated as short-term debt

(comprising the current portion of long-term debt, securities lending payable, and repurchase agreements) over total

assets (excluding separate account assets).

23

AIG Submission, p. 3. [•]

12

4.1.1 Balance Sheet Overview

Since the final determination, AIG’s total assets have decreased 9 percent, from $549 billion at

year-end 2012 to $498 billion at year-end 2016.

24

Part of this decrease can be attributed to the

divestiture of approximately $30 billion of ILFC assets that were held for sale in 2013 and

2012.

25

In addition, from 2012 to 2016, AIG’s total investments decreased 13 percent, from

$376 billion to $328 billion.

26

At the same time, AIG’s separate account assets increased by 45

percent, from $57 billion in 2012 to $83 billion in 2016.

27

These changes are in line with AIG’s

business strategy of focusing on core insurance business lines and its decision in 2008 to begin

running off its direct investment and global capital markets businesses. (See Appendix A for

AIG’s condensed consolidated balance sheet.)

4.1.2 Comparison to Peers

Table 2 compares AIG to the largest bank holding companies and other large insurers, sorted by

total assets. AIG’s ranking on this list has not changed since 2012. However, AIG has shown a

decrease for all but one metric in this table, and while AIG’s leverage ratio as measured by debt

to equity has increased slightly since 2012, it is lower than every other entity on the list other

than Berkshire Hathaway and State Farm.

24

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, p. 204; AIG Annual Report on Form

10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 170.

25

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2013, p. 211; AIG Annual Report on Form

10-K for the year ended December 31, 2014, pp. 211 and 228.

26

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, p. 204; AIG Annual Report on Form

10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 170.

27

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, p. 204; AIG Annual Report on Form

10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 170.

14

AIGFP

AIGFP has substantially shrunk its derivatives portfolio. Gross notional derivative exposures

declined from $1.6 trillion at year-end 2008 to $127 billion at year-end 2012.

28

According to

AIG, as of June 30, 2016, AIGFP is immaterial to the assets, liabilities, and revenue of AIG.

29

Sale of ILFC

On December 16, 2013, AIG entered into an agreement to sell ILFC to AerCap Holdings NV

(AerCap). In this transaction, AerCap took on approximately $21 billion of debt attributable to

ILFC.

30

The sale was completed on May 14, 2014, with AerCap Ireland Limited, a wholly

owned subsidiary of AerCap, acquiring all of the common stock of ILFC in exchange for

consideration of approximately $7.6 billion, including $2.4 billion of cash and 97.6 million

newly issued AerCap common shares.

31

On June 9, 2015, AIG completed the sale of its AerCap

shares.

32

Sale of AIG Advisor Group

On May 6, 2016, AIG completed the sale of AIG Advisor Group to Lightyear Capital and PSP

Investments for [•].

33

AIG Advisor Group included four broker-dealers: FSC Securities

Corporation, Royal Alliance Associates, SagePoint Financial, and Woodbury Financial Services.

Sale of United Guaranty Corporation

On December 31, 2016, AIG completed the sale of United Guaranty Corporation to Arch Capital

Group Limited for $3.3 billion.

34

United Guaranty Corporation is a private mortgage insurance

company with $186 billion of first-lien primary mortgage insurance in force as of September 30,

2016.

35

In the transaction, AIG received $2.2 billion in cash and $1.1 billion of Arch Capital

Group Limited convertible non-voting common-equivalent preferred stock.

36

28

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2008, p. 263; AIG Annual Report on Form

10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, p. 278.

29

AIG Submission, p. 3.

30

AerCap Press Release, AerCap to Acquire International Financial Lease Corporation (December 16, 2013).

31

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2014, p. 228.

32

AIG’s Quarterly Report on Form 10-Q for the quarter ended June 30, 2016, p. 7.

33

AIG Response to OFR Request 22, p. 1.

34

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 176.

35

AIG Current Report on Form 8-K dated Jan. 3, 2017, p. 5.

36

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 176.

15

5. TRANSMISSION CHANNEL ANALYSIS

5.1 Overview

As described in the Interpretive Guidance, the Council has identified three transmission channels

as most likely to facilitate the transmission of the negative effects of a nonbank financial

company’s material financial distress or activities to other financial firms and markets:

37

• Exposure. A nonbank financial company’s creditors, counterparties, investors, or other

market participants have exposure to the nonbank financial company that is significant

enough to materially impair those creditors, counterparties, investors, or other market

participants and thereby pose a threat to U.S. financial stability.

• Asset liquidation. A nonbank financial company holds assets that, if liquidated quickly,

would cause a fall in asset prices and thereby significantly disrupt trading or funding in

key markets or cause significant losses or funding problems for other firms with similar

holdings.

• Critical function or service. A nonbank financial company is no longer able or willing to

provide a critical function or service that is relied upon by market participants and for

which there are no ready substitutes.

In its final determination regarding AIG in 2013, the Council concluded that the threat to U.S.

financial stability posed by AIG’s material financial distress arose primarily from the exposure

and asset liquidation transmission channels, and that the critical function or service transmission

channel may exacerbate the extent to which the company’s material financial distress could be

transmitted to the broader financial system and economy.

38

The Council further concluded that

AIG’s complexity and potential difficulty to resolve could also exacerbate the risks posed by

AIG’s material financial distress across all three transmission channels.

39

Based on its analysis, the Council has identified significant developments and conducted

additional analyses that materially affect the conclusions set forth in the Council Basis.

5.2 Exposure Transmission Channel

As noted above, under the exposure transmission channel, the Council considers the exposures

that a nonbank financial company’s creditors, counterparties, investors, or other market

participants have to the nonbank financial company.

At the time of the final determination, the Council determined that the principal exposures

related to AIG’s insurance products stemmed from the exposures of institutional contract holders

and retail policyholders. The company’s institutional products included AIG’s pension products,

stable value wraps, and bank- and corporate-owned life insurance (BOLI and COLI,

37

12 C.F.R. part 1310.

38

Council Basis, p. 7.

39

Council Basis, p. 7.

16

respectively). The Council found that losses to large financial institutions could impair their

provision of financial services, while exposures of non-financial entities may directly and

adversely affect their economic activity. With respect to retail policyholders’ exposures to AIG,

the Council focused on the potential for policyholders to withdraw from AIG due to their

concerns about the potential losses they could incur in the event of AIG’s material financial

distress. The Council found that these policyholder withdrawals could, in turn, force AIG to

liquidate assets to satisfy its obligations. As a result, much of the Council’s analysis regarding

the exposures of retail policyholders related more to the potential transmission of risk through

the asset liquidation transmission channel. Those potential asset liquidation risks are addressed

in section 5.3 below. With respect to exposures arising from AIG’s retail products, the Council

also focused on the potential for state guaranty associations (GAs) to mitigate or exacerbate the

risks arising from policyholders’ exposures; the GAs are discussed below in section 5.2.2.

In addition to the exposures to AIG arising from the company’s insurance products, the Council

determined that AIG’s capital markets activities were another source of direct exposures to AIG.

The Council determined that while individual exposures of firms to AIG could be considered

small relative to the firms’ capital, the aggregate exposures were significant enough that AIG’s

material financial distress could aggravate losses to financial firms and contribute to material

impairment in the functioning of key financial markets or the provision of financial services by

AIG’s counterparties, and that the resulting contraction in the availability of credit could damage

the broader economy.

Based on the analysis below, capital markets exposures to AIG have decreased substantially, and

exposures arising from AIG’s insurance products do not appear to contribute significantly to the

threat that the company’s distress could pose to U.S. financial stability through the exposure

transmission channel. Key factors include the following:

• Direct and indirect capital markets exposures to AIG have decreased substantially since

2012 as AIG has exited certain business lines and transaction types. In particular, AIG

has reduced the amounts of its total debt outstanding, short-term debt, derivatives,

securities lending, repurchase agreements, and total assets, in some cases significantly.

• Exposures of institutional policyholders arising from AIG’s general account insurance

products are roughly similar to 2012 [•].

40

AIG’s stable value wrap products increase the

potential risks that AIG’s material financial distress could pose to certain counterparties

but do not appear to contribute significantly to the threat that the company’s distress

could pose to U.S. financial stability because of the nature of the product and the diffuse

market participants who would ultimately bear these losses.

• Exposures of retail policyholders arising from AIG’s general account insurance products

are roughly similar to 2012 but do not contribute significantly to the risk that material

financial distress at AIG could pose to U.S. financial stability through the exposure

transmission channel. Additional analysis, described in section 5.2.2 below, has been

conducted for purposes of this reevaluation regarding the potential effects of these

40

Council Basis, p. 29. AIG Response to OFR Request 4, December 31, 2016.

17

liabilities on state guaranty associations, including the effects of factors that would

reduce the guaranty associations’ obligations in the event of the insolvency of AIG’s

insurance subsidiaries.

5.2.1 Exposures Arising from AIG’s Capital Markets Activities

Direct and indirect exposures of financial market participants to a nonbank financial company

experiencing material financial distress can impair those market participants or the financial

markets in which they participate and thereby pose a threat to financial stability. Even if

individual exposures are relatively small, the direct and indirect exposures can be large enough

in the aggregate for a firm’s material financial distress to have a destabilizing effect on financial

markets. At AIG, these capital markets exposures include the company’s outstanding

securities,

41

derivatives, repurchase agreements, and securities lending activities.

Capital markets exposures to AIG have substantially decreased since the Council’s determination

regarding AIG (see Table 3, which includes data from 2007 for historical context). Since 2012:

• AIG’s outstanding long-term debt has decreased by 58 percent, from $73 billion to $31

billion;

42

• Derivatives exposures on a gross notional basis have decreased by 6 percent, from $193

billion to $181 billion, and on a fair value basis have decreased by 50 percent, from $4.1

billion to $2.0 billion;

43

• Aggregate liabilities associated with securities lending, repurchase agreements, and short-

term debt have decreased by 57 percent, from $14 billion to $6.3 billion; and

• The notional amount of single-name credit default swaps outstanding for which AIG is

the reference entity has decreased by 87 percent, from $70 billion to $9.4 billion.

44

41

AIG’s shareholders would be expected to incur losses in the event of AIG’s material financial distress. However,

as noted in the Council Basis, losses arising from a decrease in the value of AIG’s common equity, by themselves,

would not generally constitute a threat to financial stability. AIG’s market capitalization increased from $52 billion

as of year-end 2012 to $65 billion as of year-end 2016. Bloomberg, as of July 13, 2017.

42

This long-term debt figure for 2012 includes $24.3 billion of debt issued by ILFC. Long-term debt figures include

the current portion of long-term debt.

43

The notional and fair value of derivatives liabilities excludes embedded derivatives, which totaled $1.3 billion in

2012 and $3.1 billion in 2016.

44

The dollar amount of CDS referencing AIG on a stand-alone basis has fallen by about 75 percent (from $38

billion to $9 billon), although AIG’s ranking has moved up compared to other institutions. The dollar decline is due

in part to the fact that the CDS market is smaller today than at the time of the final determination.

19

Limited data is available regarding the identity of the beneficial owners of AIG’s outstanding

debt securities. Record holders can be identified for $8.8 billion of AIG’s long-term debt, as

shown in Table 5, according to public data available from Bloomberg. However, although these

firms are the record holders, they are not likely the beneficial owners of a significant portion of

these securities; rather, these debt holdings likely constitute investments of other institutional and

retail investors. Further, the identities of the record or beneficial owners of the remaining 65

percent of AIG’s outstanding debt are unknown. That said, based on the available data, the

largest identified record holders of AIG’s publicly traded debt have significantly smaller

holdings than in 2012. At that time, the largest holders were Allianz (over $9.1 billion) and

Vanguard Group and Fidelity (each with over $1 billion).

46

As of year-end 2016, the largest

holder, Vanguard Group, holds $0.6 billion.

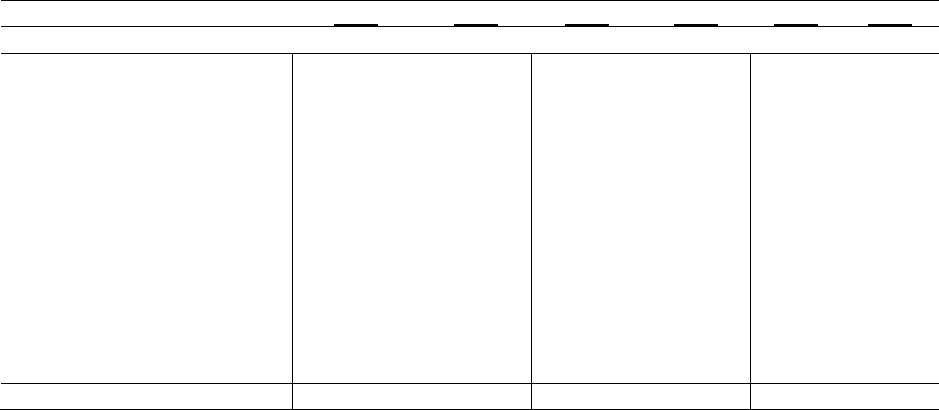

Table 5: Top Known Holders of AIG Debt ($ Millions)

Company (2012)

Value of AIG

Debt Held (2012)

Company (2016)

Value of AIG

Debt Held (2016)

Allianz

9,088

Vanguard Group

620

Vanguard Group

1,389

BlackRock

453

Fidelity

1,265

Allianz

443

BlackRock

688

Prudential

417

Loomis Sayles

523

Fidelity

394

Banc One (JPMorgan Chase)

426

Northwestern Mutual

289

Franklin Resources

379

TIAA

273

Capital Research & Mgmt.

368

JPMorgan Chase

266

T. Rowe Price

258

PIMCO

193

Dodge & Cox

240

MFS Investments

192

Source: Council Basis, p. 42; Bloomberg, as of May 16, 2017.

Derivatives

AIG’s derivatives activity is another source of exposure to the company. The majority of AIG’s

derivatives counterparties are other large financial intermediaries that are interconnected with

one another and the rest of the financial sector. Exposures of these counterparties to AIG could

result in direct losses to those firms as a result of AIG’s material financial distress.

AIG’s gross notional amount of derivatives outstanding has decreased 6 percent since 2012, to

$181 billion.

47

Over the same time period, AIG’s net derivatives liability decreased by over 50

46

Council Basis, p. 42.

47

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 234; AIG Annual Report on Form

10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, p. 277. As of year-end 2016, by gross notional amount, AIG had $96.2

billion of interest rate derivatives, $23.3 billion of foreign exchange derivatives, $22.8 billion of equity derivatives,

$0.9 billion of credit derivatives, and $37.7 billion of other derivatives.

20

percent, to $2.0 billion.

48

AIG’s net derivatives liability reflects the effects of counterparty

netting adjustments and offsetting cash collateral, which totaled $1.3 billion and $1.5 billion in

2016, respectively, but does not reflect an additional $3 billion of non-cash collateral posted by

AIG to counterparties.

49

AIG’s largest derivatives counterparties are shown in Table 6 by major contract type. The gross

notional amount of derivatives outstanding associated with the top 10 counterparties has [•].

50

The top 10 derivatives counterparties represented [•].

51

Table 6: AIG’s Top 10 Derivatives Counterparties by Gross Notional Amount ($ Millions)

Counterparty

FX

Equity

Credit

Interest

Rates

Total

[•] [•] [•] [•] [•]

[•]

Total (Top 10 Counterparties) [•] [•] [•] [•]

[•]

AIG Total Outstanding 23,271 22,806 865 96,198

180,835

Source: AIG Response to Office of Financial Research (OFR) Request 9, Derivative Counterparties, as of December

31, 2016; AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016. Notional exposures of futures

and options exchanges totaled $18.9 billion as of year-end 2016. Counterparties are aggregated on a consolidated

basis for purposes of this table. [•]

AIG clears its interest rate derivatives contracts through futures commission merchants, which

include subsidiaries of [•].

52

For AIG’s exchange-traded derivatives, which include interest rate,

foreign exchange, and equity derivatives, AIG uses [•] as brokers. Cleared and exchange-traded

derivatives represented [•] of AIG’s total notional derivatives outstanding at year-end 2016 ([•]

over-the-counter cleared and [•] exchange-traded).

53

Thus, [•] of the notional value of AIG’s

total derivatives are uncleared, exposing those counterparties to potential losses in the event of

AIG’s material financial distress.

54

AIG has continued to wind down the CDS portfolio of AIGFP, the entity responsible for a

significant amount of AIG’s losses during the financial crisis, which was in run-off mode at the

time of the final determination.

55

The AIG Submission states that, as of June 30, 2016, legacy

48

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 234; AIG Annual Report on Form

10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, p. 277.

49

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 234; AIG Annual Report on Form

10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, p. 277.

50

AIG Response to OFR Request 9, Derivative Counterparties, as of December 31, 2016; Council Basis, p. 43.

51

AIG Response to OFR Request 9, Derivative Counterparties, as of December 31, 2016; AIG Annual Report on

Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 234; AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended

December 31, 2012, p. 277; Council Basis, p. 43.

52

AIG Response to OFR Request 9, Derivative Counterparties, as of December 31, 2016.

53

AIG Response to OFR Request 10, Centrally Cleared Derivatives, as of December 31, 2016.

54

See AIG Response to OFR Request 10, Centrally Cleared Derivatives, as of December 31, 2016.

55

Council Basis, p. 18.

22

Material financial distress at AIG could cause losses to these counterparties if AIG has

insufficient liquidity to repay cash due to the counterparties. Further, if AIG could not return the

cash in full, its counterparties may be forced to liquidate the pledged securities, which could

result in losses to the counterparty. Such losses would likely be less in cases where the pledged

securities are U.S. government or other high-quality securities than for corporate bonds. The

largest counterparties in transactions in which AIG is a borrower of cash are shown in Table 8;

the average collateral posted to counterparties during 2016 was [•] of which was corporate

bonds.

60

Table 8: Top Repurchase Agreement and Securities Lending Counterparties to AIG

($ Millions)

Company Average Collateral Received

[•] [•]

Source: AIG Response to OFR Request 11, Follow-Up, as of December 31, 2016.

Guaranteed Investment Contracts

AIG issues guaranteed investment contracts (GICs) to a variety of institutional investors and

retirement plans. These products provide guaranteed interest payments and return of principal

from the issuing insurer’s general account. If AIG were to default on these obligations, investors

would suffer losses on the principal and interest under the GICs. As of December 31, 2016, AIG

had approximately [•] of GICs outstanding [•].

61

Arrangements with Federal Home Loan Banks

Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) borrowing has become a common source of liquidity for

many financial institutions. Certain AIG insurance subsidiaries are members of FHLB

associations, which allows the insurance companies to receive cash advances against pledged

eligible securities. AIG is generally subject to the risk that the FHLB lender will declare all

advances due and payable or increase the level of haircuts assigned to pledged collateral.

AIG’s outstanding advances from FHLBs remain relatively small but increased substantially,

from $82 million in 2012 to $735 million (of which $733 million is borrowings by AIG’s

property and casualty insurance subsidiaries).

62

In addition, $429 million was due to the FHLB

of Dallas under funding agreements issued by AIG subsidiaries.

63

AIG has [•] of collateral

eligible for FHLB advances (including both pledged and available), indicating the scale of

additional FHLB advances the company could seek and therefore the FHLBs’ potential

60

AIG Response to OFR Request 11, Follow-Up, as of December 31, 2016.

61

AIG Response to OFR Request 13, as of December 31, 2016; Council Basis, p. 30.

62

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2012, pp. 127-128; AIG Annual Report on

Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, pp. 137-138.

63

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, p. 138.

23

exposures to AIG.

64

If AIG were to take significant advances against eligible collateral and

subsequently default on its obligations to the FHLBs, the FHLBs would bear the market and

credit risks associated with the pledged securities.

Capital Markets Exposures of G-SIBs to AIG

The exposures of other large financial institutions to a nonbank financial company could serve as

a mechanism by which its material financial distress could be transmitted to those firms and to

financial markets more broadly. Table 9 presents a summary of the exposures of global

systemically important banks (G-SIBs) to AIG through various types of financial instruments

and transactions. Total capital markets exposures to AIG have decreased. Total exposures of G-

SIBs to AIG [•]. No single G-SIB has an exposure greater than [•] of equity capital, and most G-

SIBs had exposures below [•]. In addition, G-SIBs’ long-term debt exposure set forth in Table 9,

which reflects only initial purchasers in AIG’s issuances due to data limitations, [•]. AIG’s net

derivative liability to G-SIBs [•]. AIG’s notional amount of outstanding derivatives with G-SIBs

[•], and the percentage of AIG’s notional derivatives with G-SIBs as a percentage of its total [•].

Finally, G-SIBs’ credit line exposures to AIG [•].

Table 9: Capital Markets Exposures of G-SIBs to AIG ($ Millions)

Derivatives

Total Potential

Exposure

Long-Term

Debt

Issuance

Credit

Lines

Repo/Sec

Lending

Notional

Net

Liability

Amount

% of

Equity

Capital

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(1+2+3+5)

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

Total G-SIB

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

Total G-SIB 2012

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

[•]

Source: AIG Response to OFR Request 1.a, as of December 31, 2016. Long-term debt based on primary issuance

in 2016. Credit lines data is based on AIG Response to OFR Request 1.d, as of December 31, 2016. Repurchase

agreements and securities lending exposures are measured by average collateral received by G-SIBs where AIG is a

cash borrower; AIG Response to OFR Request 11, Follow-Up. Net derivatives liability is the fair value of

derivatives liabilities after counterparty netting; AIG Response to OFR Request 1c as of December 31, 2016. Equity

capital figures are based on company financial statements for the year ended December 31, 2016.

* Denotes a foreign parent company. [•]

64

AIG Response to OFR Request 12, FHLB Information, as of December 31, 2016.

24

5.2.2 Exposures to AIG’s Insurance Products

The impact of AIG’s material financial distress could include the loss of pension investments or

different types of protection for institutional customers, and the loss of insurance protection or

retirement savings for individual policyholders.

As of year-end 2016, AIG had $275 billion in total insurance liabilities (including $142 billion of

life and retirement policy reserves, $77 billion of property and casualty reserves, and $20 billion

of property and casualty unearned premium reserves).

65

This is roughly similar to 2012, when

AIG had $280 billion in total insurance liabilities (including $149 billion of life and insurance

policy reserves, $88 billion of property and casualty and mortgage guaranty loss reserves, and

$22 billion of property and casualty unearned premium reserves).

66

Exposures of Institutional Policyholders and Annuity Contract Holders

Following is an analysis of exposures of large institutional contract holders, including across

AIG’s stable value wrap, BOLI and COLI, and pension products, in order to assess the

interconnectedness of AIG with major financial and non-financial entities and the effects

material financial distress at AIG could have on those counterparties.

Exposures of institutional policyholders arising from AIG’s insurance products [•]. While AIG’s

material financial distress could impose losses on pension plan sponsors, retirement plan

participants, beneficiaries of structured settlements, and pension participants, these products do

not appear to contribute significantly to the threat that the company’s distress could pose to U.S.

financial stability.

Stable Value Wrap Products

Stable value wrap contracts help trustees and investment managers of defined contribution plans

manage the potential asset-liability mismatch arising from accelerated withdrawals and the credit

risk associated with their investment portfolios. Stable value funds are a fixed income

investment option commonly offered in defined contribution plans and are designed to preserve

the total amount of participants’ principal while providing steady returns as set forth in the

contract. In the event of AIG’s material financial distress, the pension plan users of these wraps

could be forced to write down their assets from book to market value, resulting in losses for the

pension plan sponsors.

67

65

AIG Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2016, pp. 120, 170, 293; SNL Financial, as of

December 31, 2016. Non-guaranteed separate account liabilities are not generally exposed to the insurer’s credit

risk because they are insulated from claims of creditors of the insurance company. These liabilities therefore present

less risk arising from the exposure transmission channel than general account liabilities.

66

Council Basis, p. 28.

67

The Council Basis noted that AIG’s stable value wrap products, for which the notional amount wrapped was

approximately $40 billion as of December 31, 2008, were cited in testimony by the FRBNY as one of the

government’s key concerns from an AIG failure. Joint written testimony of Thomas C. Baxter and Sarah Dahlgren

25

The total notional amount wrapped by AIG has [•].

68

Table 10 lists the top 10 counterparties of

AIG’s stable value wrap products. [•]

69

Table 10: Top 10 Stable Value Wrap Counterparties ($ Billions)

Notional Value

[•]

[•]

Source: AIG Response to OFR Request 4, as of December 31, 2016.

[•] However, the counterparties to these transactions are less interconnected to the financial

system than other types of large financial institutions, such as large banks, and the sizes of these

exposures do not appear to be large enough to contribute materially to the risks that material

financial distress at AIG could pose through the exposure transmission channel.

Bank-Owned and Corporate-Owned Life Insurance (BOLI/COLI)

AIG offers BOLI and COLI products. These are universal life insurance policies that provide for

permanent life insurance with the ability to accumulate a cash value on a tax-deferred basis

through the investment of premium payments. In the event of material financial distress at AIG,

BOLI and COLI contract holders could surrender these insurance contracts for cash value, but in

the event of AIG’s material financial distress, the company may be unable to satisfy these

obligations, exposing the contract holders to losses.

As of December 31, 2016, AIG had [•] BOLI/COLI contracts with a total cash value of [•],

70

compared to [•] as of September 30, 2012.

71

As the Council noted at the time of its final

determination regarding AIG, in the event of AIG’s material financial distress, the company’s

BOLI/COLI business is small enough that it likely could be transferred to another life insurer,

mitigating the potential for contract holders to experience losses.

72

Group Annuities

AIG, through its life insurance subsidiaries, provides certain group annuity products to multiple

market segments, including state and local governments, the health services industry, institutions

of higher education, and public and secondary education institutions.

before the Congressional Oversight Panel (COP), Washington, D.C., Federal Reserve Bank of New York, COP

Hearing on TARP and Other Assistance to AIG (May 26, 2010), available at

http://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2010/bax dah100526.html

.

68

Council Basis, p. 29. AIG Response to OFR Request 4, December 31, 2016. According to the company, as of

December 31, 2016, [•].

69

Furthermore, AIG’s market share for stable value wrap products is less than 5 percent. See Stable Value

Investment Association, available at https://www.stablevalue.org/knowledge/stable-value-at-a-glance

.

70

AIG Response to OFR Request 5.

71

Council Basis, p. 29.

72

Council Basis, p. 29.

26

As of December 31, 2016, AIG had [•] in fixed accounts with guaranteed interest rates to defined

contribution plans, [•] as of December 31, 2012.

73

AIG’s material financial distress could cause

individuals in these plans to lose the protection of the account interest rate guarantees, and plan

participants could lose value in their retirement accounts.

Structured Settlements

Structured settlements are annuity contracts purchased to settle casualty claims. Generally the

covered casualty claim involves a severe injury suffered by a third party that is covered by a

property and casualty policy; often the injury involves a permanent disability or suffering. Once

the claim is settled, the property and casualty insurer purchases the annuity from a life insurance

company to provide a lifetime stream of income to the injured third party. If AIG were unable to

satisfy its structured settlement obligations due to the company’s material financial distress,

payments to beneficiaries could be interrupted or reduced, and the shortfall would revert to other

parties. Depending on the nature of the contract, losses could be passed to an assignment

company, the original property and casualty insurer, or, if the property and casualty insurer also

faced material financial distress, the insured businesses and professionals (e.g., medical

practitioners) who are first parties to the beneficiaries’ claims.

74

As of December 2016, AIG

holds [•] in reserves against these contracts,

75

compared to [•] as of September 30, 2012.

76

Pension Funds

At the time of the final determination, AIG also provided terminal funding annuities for private

pension funds through its life insurance subsidiaries. A terminal funding agreement is a contract

that is purchased by an employer that is terminating its defined benefit pension plan and

transferring the accrued benefit liabilities into a life insurer’s irrevocable group annuity.

77

[•]

78

[•]

79

Material financial distress at AIG could negatively affect the ability of its policyholders to

access investment or retirement funds.

Exposures of Retail Policyholders and Guaranty Associations

Following is an analysis of exposures of retail policyholders and the state guaranty associations

to AIG.

73

AIG Response to OFR Request, Other Questions Follow-Up Response 2; Council Basis, p. 30.

74

See Council Basis, p. 32.

75

AIG Response to OFR Request 6, as of December 31, 2016.

76

Council Basis, p. 31.

77

AIG, Single Premium Group Annuity (SPGA): Contracts for Terminating and Frozen Defined Benefit Pension

Plans, available at

http://www.aig.com/content/dam/aig/america-

canada/us/documents/brochure/singlepremgrpanncontractsagl-brochure.pdf.

78

Council Basis, p. 31.

79

AIG Response to OFR Request 7.

27

Retail Policyholders

[•]

80

In the Council Basis, the discussion of retail policyholders’ exposures to AIG focused on

the potential for policyholder concerns about the potential losses they could incur in the event of

AIG’s material financial distress to lead policyholders to withdraw from AIG, which in turn

could force AIG to liquidate assets to satisfy its obligations. As a result, that discussion included

an analysis of the potential for the GAs to mitigate the risks arising from policyholders’

exposures and an evaluation of the potential for stress to be transmitted to other life insurance

companies if the GAs were required to assess premiums on other life insurance companies to

fund GA liabilities associated with AIG’s insolvency. For purposes of this reevaluation, the

potential asset liquidation risk arising from policyholder withdrawals is addressed in section 5.3

below. Apart from the potential risks related to the GAs, discussed below, it appears that the

exposures of retail policyholders to AIG do not contribute significantly to the risks that material

financial distress at the company could pose to U.S. financial stability through the exposure

transmission channel, based on the size and product mix of AIG’s retail insurance business, the

long-term nature of these liabilities, and the protection offered by the GAs.

Impact on State Guaranty Association Capacity

State GAs for U.S. life insurance companies protect holders of certain insurance and annuity

products in the event of insolvency of the insurance company issuing those products. Upon the

filing of a court order of liquidation against an insurer in its state of domicile, the GA of each

state where the insolvent insurer’s policyholders reside is then triggered

81

to provide coverage of

claims of the failed insurer’s policyholders in that state, up to statutorily prescribed limits.

82

Obligations under certain products are not protected by GAs, either because the products are not

eligible for coverage or because a portion of the policy value exceeds the coverage limit

provided under the laws of a particular state. For example, many state guaranty funds do not

provide coverage for GICs or most commercial policies.

83

Other institutional products,

particularly unallocated annuities issued to benefit plans, may be covered by state guaranty

funds, but the coverage level is small relative to the size of the contract, and the coverage is for

80

AIG Response to OFR Request Other Questions Follow-Up Response 3, as of December 31, 2016.

81

The various GAs are not activated until a receivership of an insurer results in a state court placing the insurer’s

estate into liquidation based upon a finding that the insurer is insolvent (i.e., it cannot pay its obligations as they

become due or its assets are inadequate to satisfy its liabilities). The GAs may also be activated prior to insolvency

if a state court finds that an insurer is impaired and places the insurer into rehabilitation or conservation. This

subsection addresses the implications of insolvency at AIG or its significant subsidiaries in order to consider certain

potential effects of the company’s failure.

82

See National Organization of Life and Health Guaranty Associations (NOLHGA), The Life & Health Insurance

Guaranty Association System: The Nation’s Safety Net (2016), pp. 3-4, available at

https://www.nolhga.com/resource/code/file.cfm?ID=2515

.

83

See American Council of Life Insurers, Insurance Guaranty Associations: Frequently Asked Questions, available

at

https://www.acli.com/-/media/ACLI/Public/Files/PDFs-PUBLIC-SITE/Public-Public-Policy/guarantee-

associations-FAQ.ashx.

28

the retirement plan, not the plan participants. To the extent that AIG’s policies are not protected

by the GAs, the policyholders will experience losses if AIG is unable to satisfy its obligations.

To provide funding for payments of covered claims, each GA may, on an after-the-fact basis,

assess all licensed insurance companies doing business in that state and those companies writing

policies in the same lines of business as the insolvent insurer. Assessments may continue for a

number of years, as necessary, to reimburse the guaranty fund for its payments of covered

claims. Assessments are typically based on a percentage of each solvent insurer’s average

annual premium in each state during the three calendar years prior to the year of insolvency,

subject to a 2 percent annual cap.

84

In the event of the insolvency of an insurer the size of AIG, the various GAs’ funding needs